Abstract

A major role of the outer membrane (OM) of Gram-negative bacteria is to provide a protective permeability barrier for the cell, and proper maintenance of the OM is required for cellular viability. OM biogenesis requires the coordinated assembly of constituent lipids and proteins via dedicated OM assembly machineries. We have previously shown that, in Escherichia coli, the multicomponent YaeT complex is responsible for the assembly of OM β-barrel proteins (OMPs). This complex contains the OMP YaeT and three OM lipoproteins. Here, we report another component of the YaeT complex, the OM lipoprotein small protein A (SmpA). Strains carrying loss-of-function mutations in smpA are viable but exhibit defects in OMP assembly. Biochemical experiments show that SmpA is involved in maintaining complex stability. Taken together, these experiments establish an important role for SmpA in both the structure and function of the YaeT complex.

The outer membrane (OM) of Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, constitutes the outermost compartment of the cell and contributes to overall cellular integrity. The barrier function of the OM requires stable maintenance of a unique lipid and protein composition. It is an asymmetric bilayer with phospholipids in the inner leaflet and glycolipids, primarily LPS, in the outer leaflet (1). There are two major types of proteins in the OM, OM β-barrel proteins (OMPs) and OM lipoproteins. The OMPs consist of antiparallel β-strands, organized into a cylindrical shape, producing a β-barrel, whereas OM lipoproteins are tethered to the inner leaflet of the OM via amino-terminal lipid moieties.

All of the components of the OM are synthesized within the cytoplasm and must be subsequently targeted to the OM. Transport of these amphipathic molecules across the hydrophilic environment of the periplasm requires dedicated transport and assembly machineries. Significant progress has been made in identifying various proteins required for OM biogenesis in E. coli (2). Lipoproteins are targeted by components of the essential Lol pathway (3). The essential OM YaeT complex is required for OMP assembly (4), whereas yet another essential OM complex, Imp/RlpB, catalyzes LPS assembly (5–7). It is likely that the targeting and insertion of LPS and OMPs are in some way coordinated to maintain a proper lipid–protein ratio and preserve the integrity of the OM. Genetic evidence supporting such a homeostatic mechanism exists, because mutations in genes specifying members of the YaeT complex can suppress specific OM defects conferred by a particular mutation in imp (8–10).

Information concerning the interactions between the members of the YaeT complex has been obtained through both genetic and biochemical analysis. This complex contains the OMP YaeT and three associated OM lipoproteins, YfgL, NlpB, and YfiO (4). Cells lacking either NlpB or YfgL are viable and exhibit only minor OMP assembly defects (9, 11). The other members of the complex, YaeT and YfiO, are essential, and depletion of either of these proteins from the cell results in severe OMP targeting defects (4, 11, 12).

Here, we report an additional, nonessential component of the YaeT complex, the OM lipoprotein small protein A (SmpA). We show that SmpA plays an important role in both the stability and function of the YaeT complex.

Results

SmpA Copurifies with the YaeT Complex.

To gain insight into the structure of the YaeT complex, we have been probing the interactions between the different protein components (4, 11). Biochemical studies using wild-type and mutant proteins raised the possibility that the complex might contain an additional component(s). To address this possibility, we used a variety of different methods to purify the complex before and after cross-linking with formaldehyde. Potential interacting proteins were excised from the gel and identified by tandem mass spectrometry. One of the proteins identified was SmpA (molecular weight, 12,162.5 Da) (13). This protein was of particular interest, because a homolog of SmpA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, OmlA, has been characterized as an OM lipoprotein that functions in maintaining the cell envelope integrity (14).

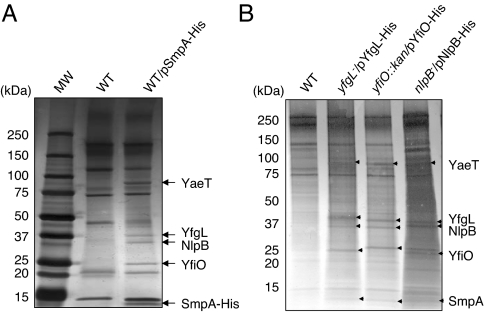

We cloned the smpA gene from the E. coli genome and modified it to express SmpA with a C-terminal His tag. This construct produced a tagged but functional SmpA protein that complemented the smpA-null phenotype discussed below (data not shown). We used this His-tagged SmpA protein for affinity purification experiments to verify its interaction with the YaeT complex. As shown in Fig. 1A, SmpA-His successfully pulled down all four previously known members of the YaeT complex. Complementary affinity purifications verified that SmpA copurifies with the YaeT complex regardless of which lipoprotein member was tagged (Fig. 1B). These experiments demonstrate that SmpA interacts directly with the YaeT complex in vivo.

Fig. 1.

SmpA copurifies with the YaeT complex. (A) Silver-stained SDS/polyacrylamide gel of samples from cell lysates of wild-type (WT), wt/pSmpA-His strains immunoprecipitated with anti-His tag antibody. (B) Silver-stained SDS/polyacrylamide gel of samples from cell lysates of WT, yfgL−/pYfgL-His, yfiO::kan/pYfiO-His, and nlpB−/pNlpB-His strains immunoprecipitated with anti-His tag antibody. MW, molecular weight.

SmpA Is Not Essential for Viability in E. coli.

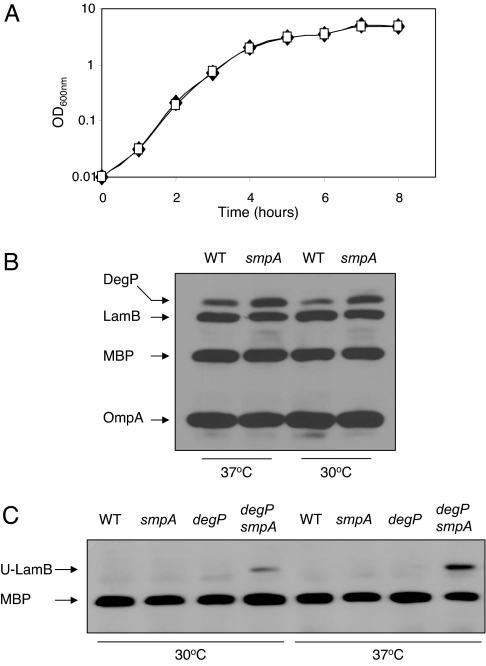

The YaeT complex is required for the assembly of OMPs into the OM (4), and two of its members, YaeT and YfiO, are essential in E. coli (4, 12). To determine whether SmpA performs an essential cellular function, we replaced the last 110 codons of the 113 codons of smpA with a gene coding for either chloramphenicol or kanamycin resistance by using previously described recombineering methods (15). Both of these mutant smpA strains were phenotypically identical in terms of growth on LB medium. Because there is no gene immediately downstream of smpA (16) and we are able to complement smpA mutant phenotypes with a functional copy of smpA on a plasmid (data not shown), any phenotype arising from an smpA-null strain would not be a consequence of polarity. We monitored the growth of strains lacking SmpA at 37°C in rich media and observed no apparent growth defect (Fig. 2A). Strains lacking SmpA grew normally at temperatures ranging from 23°C to 42°C in both rich and minimal media (data not shown). Therefore, SmpA is a nonessential member of the YaeT complex.

Fig. 2.

SmpA is not essential for growth in E. coli. (A) Growth curves for wild-type cells (♦) or smpA cells (▫) at 37°C are shown. Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm every hour for 8 h. The results of a representative experiment are shown above. (B) Levels of envelope proteins in an smpA mutant during midlogarithmic growth at 37°C and 30°C. Western blot analysis shows a very small reduction in the levels of OmpA and LamB in an smpA mutant strain when compared with a wild-type (WT) strain. Levels of the periplasmic chaperone/protease DegP are elevated 1.5- to 2-fold in an smpA mutant. (C) Unfolded LamB accumulates in an smpA degP double mutant. Cells were grown to midlogarithmic growth at 37°C and 30°C and harvested by centrifugation. These samples were gently lysed to preserve the native conformation of OMPs. Western blot analysis by using LamB antiserum was used to visualize unfolded LamB (U-LamB). Levels of MBP are shown as a loading control.

SmpA Mutants Exhibit OMP Assembly Defects.

Although SmpA is not required for cell viability, it is still possible that it plays a nonessential role in OM biogenesis. If this is true, strains lacking SmpA may exhibit increased sensitivity to various toxic small molecules (2). Indeed, smpA strains exhibited 4-fold increased sensitivity to rifampin and 2-fold increased sensitivity to cholate relative to the wild-type strain. Furthermore, smpA strains were unable to grow on medium containing 0.5% SDS and 1 mM EDTA. Therefore, the barrier function of the OM is compromised in smpA mutants.

Given that SmpA associates with the YaeT complex (Fig. 1), strains that lack this protein may be unable to efficiently assemble OMPs in the OM. For example, strains that lack YfgL, another nonessential lipoprotein member of the YaeT complex, exhibit OMP assembly defects as evidenced by decreased steady-state levels of two OMPs, LamB and OmpA (9). Similarly, we found a slight decrease in the levels of OmpA and LamB in an smpA mutant strain, whereas the levels of the periplasmic protein maltose-binding protein (MBP) were unaffected (Fig. 2B).

The slightly lower levels of OMPs in an smpA mutant may result from the degradation of mistargeted OMPs by periplasmic proteases such as DegP. Activation of the σE stress response, which is induced by the presence of misfolded OMPs in the periplasm, increases the levels of DegP (17, 18). If the loss of SmpA leads to an OMP assembly defect, DegP levels should increase. Steady-state levels of DegP were elevated 1.5- to 2-fold in an smpA mutant (Fig. 2B), reflecting the stress caused by defective assembly of OMPs in this strain.

To directly observe the folding status of OMPs in various mutants, we used a gentle-lysis protocol, which preserves the native conformation of OMPs (19). Normally, processed LamB monomer assumes a folded structure that subsequently forms trimers in the OM (20). When OMP assembly is compromised, the accumulation of steady-state levels of unfolded LamB monomer represents a population of LamB molecules that is unable to assemble properly into trimers. However, unfolded LamB is often hard to detect because it is rapidly degraded by the DegP protease (19). Indeed, although we were unable to detect any unfolded LamB monomer in an smpA mutant, we observed a significant amount of unfolded LamB in an smpA degP double mutant at both 30°C and 37°C (Fig. 2C). Based on these results, we suggest that unfolded LamB accumulates in cells lacking SmpA and is rapidly degraded by DegP. Thus, smpA mutants exhibit minor defects in the assembly of OMPs.

SmpA Affects the Stability of the Multiprotein YaeT Complex.

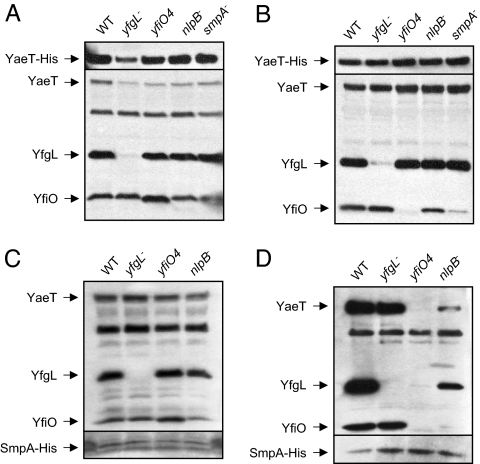

We have previously shown that affinity purification of a particular His-tagged member of the complex in a wild-type background allows copurification of all other complex members (4) (Fig. 1). When these same experiments are performed in backgrounds defective in any one component of the complex, these interactions are weakened to varying degrees. The absence of nonessential components or the presence of defective mutant proteins destabilize the interaction between the His-tagged protein and other components of the complex, which can be judged by the amount of proteins that copurifies with the His-tagged protein in each mutant strain. This type of analysis allows us to determine the relevant contributions of each protein to the stability of the complex as a whole. By using this method, we have previously shown that the YaeT6 mutation does not affect the stability of the complex (8), that YaeT interacts with YfgL independently of YfiO and NlpB, and that stable contacts between NlpB and YaeT complex require the C terminus of YfiO (11).

Because yfiO is an essential gene, we used partial loss-of-function mutations to determine how those mutant phenotypes are altered in the context of smpA mutants (11). The yfiO4 and yfiO5 mutations, collectively referred to as the yfiO(ΔC-term) mutants, produce C-terminally truncated YfiO proteins. Both mutations result in OMP assembly defects and increased OM sensitivity (11), with yfiO4 being the less severe of the two yfiO(ΔC-term) mutations. Recall that, in an earlier study, we were unable to determine whether defects in yfiO4 and yfiO5 mutants were caused by a defective mutant protein, lower levels of YfiO, or a combination of the two (11). Use of an antibody directed against YfiO allowed us to assess the levels of YfiO protein in yfiO4 and yfiO5 mutants. Western blotting analysis revealed that the levels of YfiO in the yfiO(ΔC-term) mutants are significantly reduced at 37°C (data not shown). However, steady-state levels of both mutant proteins are stabilized at 30°C, with steady-state levels in the yfiO4 mutant comparable with that of wild type (see below). Consequently, the remainder of the biochemical and genetic experiments were performed at 30°C.

By using these affinity purification methods, we sought to further develop our understanding of the interactions among the components of the YaeT complex and to address the relative arrangement of SmpA within the complex. As shown in Fig. 3A and C, the protein levels of YaeT complex members from total membrane fractions were equivalent regardless of genetic background at 30°C. His-tagged YaeT copurified with YfiO and YfgL (Fig. 3 A vs. B, lane 1). The yfiO4 mutation disrupted the interaction between YaeT and YfiO, but not the interaction between YaeT and YfgL (Fig. 3 A vs. B, lane 3). The loss of SmpA also resulted in decreased ability of His-tagged YaeT to copurify with YfiO (Fig. 3 A vs. B, lane 5), although the defect was not as large as seen in the YfiO4 background. We conclude that the structural defects seen in a yfiO4 mutant are a result of an inability of a mutant YfiO protein to stably associate with the rest of the complex and not because of lower levels of YfiO, because these experiments were conducted under conditions where the steady-state levels of truncated protein approach those of the wild-type YfiO. Furthermore, we suggest that SmpA is required to maintain a stable interaction between YfiO and YaeT.

Fig. 3.

Affinity purification of the YaeT complex in lipoprotein mutants. (A–D) Affinity purification was performed in WT and lipoprotein mutant strains that contain pYaeT-His (A and B) and pSmpA-His (C and D), respectively. (A and C) Protein levels in the total membrane fraction isolated from cells before any purification. (B and D) Samples after they have passed through an Ni-affinity column. Samples were blotted against antibodies that recognize YaeT, YfgL, and YfiO and the His tag.

To further probe these interactions, we performed the same experiment by using a His-tagged SmpA protein. The lack of YfgL did not affect the ability of His-tagged SmpA to copurify with other complex members (Fig. 3 C vs. D, lane 2). However, the yfiO4 mutation decreases the ability of His-tagged SmpA to copurify with the rest of the members of the complex (Fig. 3 C vs. D, lane 3). Moreover, the loss of NlpB results in a decreased ability of His-tagged SmpA to interact with other complex members as well (Fig. 3 C vs. D, lane 4). Based on these data, we conclude that SmpA, NlpB, and YfiO interact with each other and with YaeT in a manner independent of YfgL.

Genetic Interactions Demonstrate That SmpA Is a Functional Member of the YaeT Complex.

We have presented biochemical evidence that the SmpA protein is a member of the YaeT complex. To provide evidence supporting these interactions in vivo, we have constructed all possible double mutant combinations between smpA and other known members of the YaeT complex. The logic behind these experiments is as follows: If one component of the complex is compromised, as it is in single mutants, the effect on OMP biogenesis may be minimal. However, if two components are compromised, the defect may be exacerbated, resulting in a synthetic phenotype.

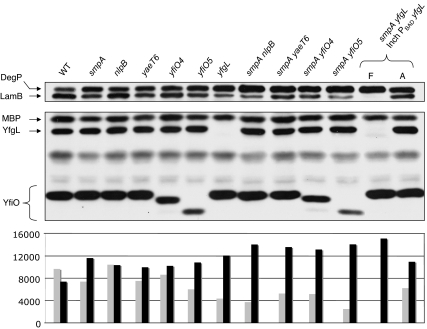

To assess the assembly of OMPs in the various smpA double mutants, we monitored the steady-state levels of LamB, OmpA, and DegP in these mutants at 30°C. Levels of OMPs were reduced to varying degrees in the different double mutants, whereas levels of the periplasmic protease/chaperone DegP increased (Fig. 4). The levels of DegP were proportional to the severity of the observed OMP assembly defect. Mutant strains that contained lower levels of LamB and OmpA contained higher steady-state levels of DegP. The evident synthetic phenotypes provide support that SmpA is a functionally relevant member of the YaeT complex.

Fig. 4.

smpA genetic interactions. Western blot analysis shows the levels of DegP, LamB, MBP, YfgL, and YfiO proteins in strains carrying mutations that affect different YaeT complex members and in smpA double mutants during midlogarithmic growth at 30°C. The smpA yfgL depletion strain was grown in the presence of l-arabinose (A) to induce expression of yfgL or in the presence of d-fucose (F) to prevent its expression. Below the Western blots is a chart that shows the quantification of LamB (gray bars) and DegP (black bars). The values of the y axis represent the areas of the bands as quantified by using ImageJ image-processing software.

The phenotypes of the smpA double mutants varied from severe defects in OM biogenesis to true synthetic lethality. Whereas both nlpB and smpA single mutants exhibited modest OMP assembly defects, the nlpB smpA double mutant strain was severely defective with respect to its ability to properly assemble OMPs. Similar phenotypes were observed when an smpA mutation was combined with yaeT and yfiO mutant alleles. In addition, the yfiO5 smpA and yaeT6 smpA double mutants grew significantly slower than either of the single mutants (data not shown). All of these phenotypes were exacerbated at 37°C, likely reflecting an inability to satisfy the increased demand for OMP assembly caused by an increased growth rate at higher temperatures.

We were able to introduce a yfgL::kan allele into an smpA mutant background by P1 transduction, but we were unable to further purify these transductants. To confirm this synthetic lethality, we constructed a yfgL depletion strain to observe the phenotype of this particular double mutant. When this strain is depleted of YfgL, dramatic OMP assembly defects occur, which ultimately result in cell death (Fig. 4).

Discussion

We have previously reported that YaeT exists in a multiprotein complex with three OM lipoproteins, YfgL, YfiO, and NlpB in E. coli (4). Here, we have identified a new component of the YaeT complex, the OM lipoprotein SmpA. We show that SmpA is not an essential member of the complex and that loss of SmpA causes only mild OM defects. However, smpA strains that harbor an additional mutation in a gene encoding for another YaeT complex member exhibit a synthetic phenotype that is much worse than either of the singly mutant parents. These genetic interactions complement our biochemical results demonstrating that SmpA is a structurally and functionally important component of the YaeT complex.

In E. coli, defects in OMP folding as well as changes in OM composition trigger both the σE and Cpx stress responses (21, 22). These stress responses help to alleviate problems in the cell envelope by up-regulating the expression of genes encoding periplasmic folding factors, proteases, and proteins involved in biosynthesis and assembly of cell envelope components. Approximately 100 genes have been predicted to be members of the σE and Cpx regulons in E. coli (23, 24). The genes that encode all of the components of the YaeT complex are all members of the σE regulon (12, 24–27). Therefore, like the genes encoding other members of the YaeT complex, smpA expression is up-regulated by the σE regulon when the OM biogenesis is compromised. In a genome-wide profiling study to look for genes that might be regulated by the CpxA/R envelope stress response in E. coli, multiple potential CpxR-P binding sites were identified in the promoter region of smpA (23). However, additional experiments are needed to verify the physiological significance of these observations.

Mutations in members of the YaeT complex show increased sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics, bile salts, and detergents (8, 9). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa homolog of smpA, omlA (39% sequence identity), was reported to be an OM lipoprotein (14), and omlA mutants showed hypersensitivity to anionic detergents such as SDS and increased sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics such as rifampin (14). Based on these phenotypes, it is safe to assume that the cell envelope of P. aeruginosa is compromised in omlA mutants (14). This is also true in E. coli, because we have observed increased sensitivity to cholate, rifampin, and SDS/EDTA in smpA mutants in addition to slight defects in OMP biogenesis (Fig. 4).

Affinity purification of the YaeT complex in strains that carry mutations in different lipoprotein components of the complex provide us with information about how the complex is organized and stabilized. Based on this type of analysis, we proposed that YaeT contacts both YfiO and YfgL directly and that the C terminus of YfiO is required to maintain a stable interaction between NlpB and the rest of the complex (11). Here, we have shown that SmpA, a new component in the multiprotein YaeT complex, associates with YfiO and NlpB independent of YfgL (Fig. 3). The identification of this additional component may explain why OM defects are worse in doubly mutant nlpB− yfiOΔC-term cells than in either of the single mutants because there are more interdependent interactions than we originally detected.

Clearly, three lipoproteins in the YaeT complex, YfgL, NlpB, and SmpA, perform nonessential function(s) because strains lacking each one of these three proteins individually are viable and exhibit rather modest OM defects. It follows therefore that the function(s) performed by these three lipoproteins serve instead to increase the rate and/or the efficiency of OMP assembly, either directly or indirectly. Indeed, strains lacking YfgL exhibit defects in the rate and/or the efficiency at which OMP assembly intermediates are delivered to the YaeT complex, but once delivered, OMP assembly appears to occur at normal rates (28). As noted above, YfgL interacts with YaeT in a manner that is independent of NlpB, SmpA, and YfiO and vice versa. In light of these structural differences, it will be of interest to determine whether NlpB and SmpA function at different steps in the complex process of OMP assembly.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Plasmids.

Strains are listed in Table 1. All strains were constructed by using standard microbiological techniques. The chromosomal disruption of the smpA gene was generated according to the procedure described by Datsenko and Wanner (15). PCR products were generated by using the following primers (5′-TGAGCCACGTACTGCTCGGGCCCGAAAAGGAATCAAATCACTATGCGCTGTTTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG-3′ and 5′-CAGCGCAGGTTTGTTATCAATATTGGTCAACACACCGCTACTGTTAAAGGTGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′) from the template plasmids pKD3 and pKD4. The PCR products were gel-purified and resuspended in distilled water. One hundred microliters of cells and 10–50 ng of PCR product were used to transform the lambda-red strain DY378 (29). Mutations were verified by using PCR with primers external to the ORF of smpA. Sequences are available upon request. All smpA mutants and double mutants were constructed by moving either smpA::cam or smpA::kan into the recipient strain by using P1 transduction.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strains or plasmids | Genotype and relevant features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| MC4100 | F−araD139Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 flb5301 deoC1 ptsF25 thi | 30 |

| DY378 | W3110 λcI857 Δ(cro-bioA) | 29 |

| JGS212 | MC4100 smpA::cam | This study |

| JGS213 | MC4100 smpA::kan | This study |

| JCM158 | MC4100 ara−, spontaneous arabinose-resistant | 11 |

| JCM175 | JCM158 yfgL::kan | This study |

| JCM252 | JCM158 yfgL::kan Δ(λatt-lom)::blaPBADyfgL araC | This study |

| JCM304 | JCM158 nlpB::kan | 11 |

| JCM344 | JCM158 yfiO4::cam | 11 |

| JCM345 | JCM158 yfiO5::cam | 11 |

| JCM375 | JCM158 smpA::cam | This study |

| JCM456 | JCM158 yfiO4::cam smpA::cam | This study |

| JCM457 | JCM158 yfiO5::cam smpA::cam | This study |

| JCM473 | JCM252 smpA::cam | This study |

| JCM474 | JCM158 smpA::cam nlpB::kan | This study |

| JCM480 | JCM158 yaeT6 yadG::cam | This study |

| JCM494 | JCM158 smpA::cam yaeT6 yadG::cam | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD18 | Cloning vector; PBAD-dependent expression | Invitrogen |

| pKD4 | Contains a kanamycin-resistance cassette | 15 |

| pKD3 | Contains a chloramphenicol-resistance cassette | 15 |

| pET42a(+) | Cloning vector with His tag | Novagen |

| pET22b(+) | Cloning vector | Novagen |

| pET22–42 | Cloning vector derived from pET22b(+) and pET42a(+) | This study |

| pYfgL-His | Encodes C-terminal His-tagged YfgL | 4 |

| pYfiO-His | Encodes C-terminal His-tagged YfiO | 4 |

| pNlpB-His | Encodes C-terminal His-tagged NlpB | 4 |

| pSmpA-His | Encodes C-terminal His8-tagged SmpA | This study |

| pYaeT-His | Encodes N-terminal His6-tagged YaeT | This study |

| pBAD18::yfgL | PBAD-yfgLon pBAD18 vector | This study |

The multiple cloning site of the pET42a(+) vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) was moved into the pET22b(+) vector (Novagen) by using XbaI and Bpu1102I restriction sites to create pET22–42. Primers 5′-ATGACATATGCGCTGTAAAACGCTGACTGC-3′ and 5′-ACGTCTCGAGGTTACCACTCAGCGCAGGTTTGTTATCAATATTG-3′ were used to amplify smpA from MC4100 genomic DNA by using PCR. The fragment was introduced into pET22–42 by using XhoI and NdeI restriction enzymes. The resulting construct, pSmpA-His, expresses C-terminally tagged SmpA that complements the smpA chromosomal disruption described above.

To construct a strain carrying a second, arabinose-inducible copy of yfgL, we first cloned yfgL into pBAD18 by using primers 5′-TTGAATTCGTATTACATTTTGAGGA-3′ and 5′-TTTCTAGATTATGTATTGCTGCTGT-3′ to amplify the gene from the MC4100 chromosome and by using EcoRI and XbaI restriction enzymes for cloning. Next, the portion of the plasmid containing araC PBAD-yfgL bla was integrated into the λ-attachment site by using the protocol established by Boyd et al. (30) to create JCM252 (Table 1).

The plasmid expressing His-tagged YaeT, pYaeT-His, was constructed such that an in-frame hexahistidine tag was incorporated near the N terminus of the mature sequence. Two PCR products were amplified from the MC4100 genome, corresponding to the N-terminal plus 6x-His and C-terminal sequences, respectively, ligated together, and reamplified to obtain the full-length yaeT-His DNA fragment. The N-terminal fragment of yaeT corresponding to the sequence encoding the first 21 amino acids of the protein was amplified by using primers 5′-GTCCTAGAGCATATGGCGATGAAAAAGTTGC-3′ (NdeI) and 5′-ACACCTGCAGCATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGAGCACCGTATACGGTGG-3′ (PstI). The C-terminal primer for this reaction incorporated sequence coding for the amino acids HHHHHHAA. The C-terminal fragment of yaeT-His was amplified by using primers 5′-ACACGCTGCAGAAGGGTTCGTAGTGAAAGATATTC-3′ (PstI) and 5′-ACACGCGGCCGCTTACCAGGTTTTACCGATGTTAAACTG-3′ (NotI). The two PCR fragments were digested with PstI, ligated together, and reamplified by using the external primers described above. This PCR product was digested with NdeI and NotI and ligated into pET22b(+) treated with the same enzymes. The resulting construct encodes the His-tagged YaeT with an insertion of eight residues, HHHHHHAA, between Ala-21 and Glu-22. Strains carrying this plasmid can be crossed via a P1 lysate with a yaeT null allele (yaeT::kan) (4), demonstrating that the His-YaeT protein expressed from pYaeT-His is functional.

Media and Growth Conditions.

LB was prepared as previously described (31). When necessary, media were supplemented with 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml kanamycin, 5 μg/ml rifampin, or 25 μg/ml tetracycline. All bacterial cultures were grown under aerobic conditions at 30°C unless otherwise noted. Minimum inhibitory concentration experiments for cholate and rifampin were performed as described previously (8).

Western Blot Analysis.

Cultures were grown overnight in LB medium, with strain JCM473 supplemented with 0.025% l-arabinose. Cultures were diluted the following day into fresh media 1:100, with strain JCM473 subcultured at the same dilution into medium containing 0.025% of either l-arabinose or the competitive inhibitor of arabinose, d-fucose (32). After growth to an OD600 of 0.4–0.45, 1-ml samples were harvested by centrifugation and immediately resuspended in SDS loading buffer in a volume in milliliters equal to the OD600 ÷ 6. After boiling for 10 min, equal volumes were loaded onto 12% polyacrylamide gels. Gentle lysis was performed on relevant samples as described previously (19). After electrophoresis, gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies used to detect LamB and OmpA (1:15,000 dilution) (18), MBP (1:15,000 dilution) (19), DegP (1:30,000 dilution) (33), YfgL (1:10,000 dilution) (4), YaeT (1:3,000) (this study), and YfiO (1:20,000 dilution) (this study). The YaeT antibody was generated against the first 15 residues of the mature protein (AEGFVVKDIHFEGLQ) (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA). Donkey anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) conjugate was used as the secondary antibody at a concentration of 1:8,000. ECL (Amersham Biosciences) and XAR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) were used to visualize the protein bands. Protein bands were analyzed with gel image analysis software (ImageJ Software).

To generate the YfiO antibody, His-tagged cells expressing signal sequenceless YfiO were lysed by French press and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The soluble fraction was subjected to Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity purification as described below. The eluted solution was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 8) and 150 mM NaCl. The resulting protein preparation was used to generate a rabbit polyclonal antiserum (Princeton Animal Facility, Princeton University).

Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were grown in the 50 ml of LB media to an OD600 of ≈0.6 and harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The cells were resuspended in 1 ml of Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 1% ZW3-14 and supplemented with 100 μg/ml lysozyme, 50 μg/ml DNase I, and 50 μg/ml RNase. Cells were lysed by incubating the mixture at room temperature for 20 min on a shaker. The lysate was then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was transferred into a new Eppendorf tube. A total of 4 μg of anti-5His monoclonal antibody (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was added into the lysate, and the mixture was shaken at 4°C for 1 h. A total of 60 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added, and the mixture was shaken for another hour at 4°C. This mixture was then loaded into a micro bio-spin column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and the beads were washed with 3 ml of 1× immunoprecipitation buffer (Sigma–Aldrich) and then eluted with 50 μl of boiling SDS-sample buffer without 2-mercaptoethanol. A total of 25 μl of eluate was used for SDS/PAGE analysis. Silver stain was conducted by using the Silver Stain Plus kit from Bio-Rad and by following the protocol therein.

Affinity Purification.

A total of 250 ml of culture was grown in LB media to midlogarithmic growth (OD600, 0.4–0.6). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. Cells were lysed in 2 ml of TBS (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl), 2% Triton X-100, and 10 mM EDTA, supplemented with 100 μg/ml lysozyme and 50 μg/ml DNase I and RNase by shaking at room temperature for 10 min. MgCl2 solution was added to a final concentration of 10 mM, and the suspension was shaken for another 10 min. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove unbroken cells and cell debris. The clear lysate was exchanged into buffer TBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 20 mM imidazole by using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The lysate was loaded twice into a column packed with 0.5 ml of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen), which had been preequilibrated with the previous buffer. The column was washed with 10 ml of TBS, 0.05% N-dodecyl-β-maltoside, and 20 mM imidazole, and eluted with 5 ml of TBS, 0.05% N-dodecyl-β-maltoside, and 200 mM imidazole. The eluate was concentrated in an ultrafiltration device (Amicon Ultra; Millipore, Beverly, MA; MWCO 5K) by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for ≈2 h to a volume of ≈50 μl. Samples were mixed 1:1 with SDS loading buffer and boiled for 10 min, and equal volumes were loaded onto 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis, gels were transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with antibodies as described above. YfiO, YfgL, YaeT, and His antibodies were all used at a dilution of 1:3,000.

Cellular Protein Levels in Different YaeT-His and SmpA-His Strains.

To adequately detect cellular levels of YaeT-His, YfgL, YfiO, and SmpA-His, the membrane fraction of cell cultures was isolated. A total of 250 ml of culture was grown in LB media to OD600 ∼ 0.6. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The cells were lysed in 10 ml of TBS (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) and supplemented with 100 μg/ml lysozyme and 50 μg/ml DNase I and RNase by passage through a French pressure cell. Unlysed cells were pelleted at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The membrane fraction was pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The membrane was resuspended in 250 μl of TBS, 2% Triton X-100, and 10 mM EDTA, and insoluble lipids were again pelleted at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The soluble fraction was mixed 1:1 with SDS loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. Equal volumes were loaded onto 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis, gels were transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with antibodies as described above.

Abbreviations

- OM

outer membrane

- OMP

outer membrane β-barrel protein

- SmpA

small protein A

- MBP

maltose-binding protein

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kamio Y, Nikaido H. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2561–2570. doi: 10.1021/bi00657a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruiz N, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:57–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narita S, Tokuda H. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu T, Malinverni J, Ruiz N, Kim S, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. Cell. 2005;121:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos MP, Tefsen B, Geurtsen J, Tommassen J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9417–9422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402340101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun M, Silhavy TJ. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1289–1302. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu T, McCandlish AC, Gronenberg LS, Chng SS, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11754–11759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604744103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz N, Wu T, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:385–395. doi: 10.1021/cb600128v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz N, Falcone B, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. Cell. 2005;121:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikaido H. Chem Biol. 2005;12:507–509. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malinverni JC, Werner J, Kim S, Sklar JG, Kahne D, Misra R, Silhavy TJ. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onufryk C, Crouch ML, Fang FC, Gross CA. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4552–4561. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4552-4561.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miczak A, Chauhan AK, Apirion D. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3271–3272. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3271-3272.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochsner UA, Vasil AI, Johnson Z, Vasil ML. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1099–1109. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1099-1109.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blattner FR, Plunkett G, III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, et al. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mecsas J, Rouviere PE, Erickson JW, Donohue TJ, Gross CA. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2618–2628. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh NP, Alba BM, Bose B, Gross CA, Sauer RT. Cell. 2003;113:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra R, Peterson A, Ferenci T, Silhavy TJ. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:13592–13597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouviere PE, Gross CA. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3170–3182. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duguay AR, Silhavy TJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1694:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz N, Silhavy TJ. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Wulf P, McGuire AM, Liu X, Lin EC. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26652–26661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203487200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodius VA, Suh WC, Nonaka G, West J, Gross CA. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dartigalongue C, Loferer H, Raina S. EMBO J. 2001;20:5908–5918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabir MS, Yamashita D, Koyama S, Oshima T, Kurokawa K, Maeda M, Tsunedomi R, Murata M, Wada C, Mori H, et al. Microbiology. 2005;151:2721–2735. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rezuchova B, Miticka H, Homerova D, Roberts M, Kormanec J. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;225:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ureta AR, Endres RG, Wingreen NS, Silhavy TJ. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:446–454. doi: 10.1128/JB.01103-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu D, Ellis HM, Lee EC, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Court DL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5978–5983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100127597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd D, Weiss DS, Chen JC, Beckwith J. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:842–847. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.842-847.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silhavy TJ, Berman ML, Enquist LW. Experiments with Gene Fusions. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee N, Wilcox G, Gielow W, Arnold J, Cleary P, Englesberg E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:634–638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.3.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isaac DD, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ, Silhavy TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17775–17779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508936102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]