Abstract

Neuropilin (Nrp) is a cell surface receptor with essential roles in angiogenesis and axon guidance. Interactions between Nrp and the positively charged C termini of its ligands, VEGF and semaphorin, are mediated by Nrp domains b1 and b2, which share homology to coagulation factor domains. We report here the crystal structure of the tandem b1 and b2 domains of Nrp-1 (N1b1b2) and show that they form a single structural unit. Cocrystallization of N1b1b2 with Tuftsin, a peptide mimic of the VEGF C terminus, reveals the site of interaction with the basic tail of VEGF on the b1 domain. We also show that heparin promotes N1b1b2 dimerization and map the heparin binding site on N1b1b2. These results provide a detailed picture of interactions at the core of the Nrp signaling complex and establish a molecular basis for the synergistic effects of heparin on Nrp-mediated signaling.

Keywords: semaphorin, Tuftsin, VEGF

Neuropilins (Nrps) are essential cell surface receptors with central roles in both angiogenesis and axon guidance (1–3). During angiogenesis, Nrp directly binds VEGF and functions as a coreceptor for VEGF along with VEGF receptor (VEGFR)-2, one of the three VEGFR tyrosine kinases (3, 4). During neural development, Nrp directly binds semaphorin and functions as a semaphorin coreceptor with members of the plexin family (5). Additionally, interactions with both neural adhesion protein L1 and Nrp-interacting protein (NIP), have been shown to be involved in a variety of other cellular processes (6–8).

Nrp plays a stimulatory role in angiogenesis, a process critical for growth of solid tumors (reviewed in refs. 4 and 9–11). Nrp expression is observed in tumor vasculature, and overexpression promotes tumorigenesis in vivo for a variety of solid tumors including pituitary, prostate, breast, and colon cancers (12–15). In contrast, a soluble splice form containing only part of the extracellular domain of Nrp inhibits tumorigenesis (16) as do a number of peptides that block VEGF binding to Nrp (17, 18). Recent evidence has also demonstrated a role for Nrp in hematological malignancies. Nrp overexpression is observed in both multiple myeloma and acute myeloid leukemia and, in the latter case, is associated with significantly reduced survival (19, 20). Strategies to inhibit Nrp activity are thus being developed as potential antitumor therapies (reviewed in ref. 11).

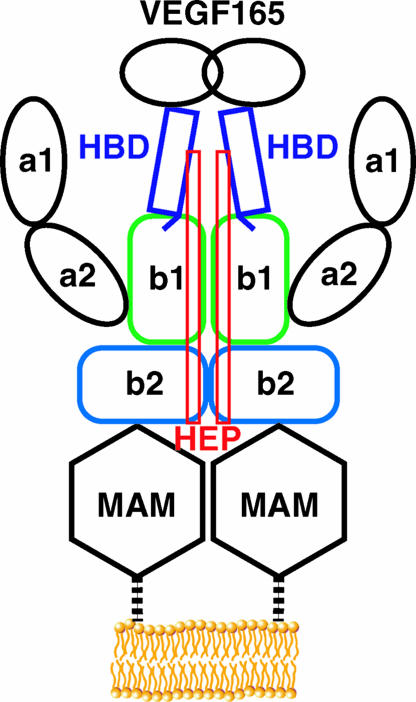

Higher eukaryotes possess two Nrp homologs, Nrp-1 and Nrp-2, which share 44% amino acid sequence identity (1). Nrp extracellular regions are composed of two complement binding CUB domains (a1 and a2) followed by two coagulation factor domains (b1 and b2), a MAM (meprin, A5, μ) domain (c1), a single membrane-spanning region, and a short cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 1A) (21, 22). The a1 and a2 domains of Nrp are essential for binding to the core seven-bladed Sema domain of semaphorin as well as contributing to interactions with VEGF (23, 24). The coagulation factor domains b1 and b2 contain the high-affinity binding site for the basic heparin binding domain (HBD) of VEGF165 as well as the basic tail of semaphorin and heparin (24, 25). The MAM domain of Nrp has been shown to be necessary, but not sufficient, for oligomerization, and can mediate both homo- and heterooligomer formation between Nrp-1 and Nrp-2 (25, 26). Both Nrp-1 and Nrp-2 interact with members of the VEGF and semaphorin families of ligands and VEGFR and plexin families of receptors. They differ, however, in their cell-specific expression, transcriptional control, and substrate specificity among ligands and coreceptors.

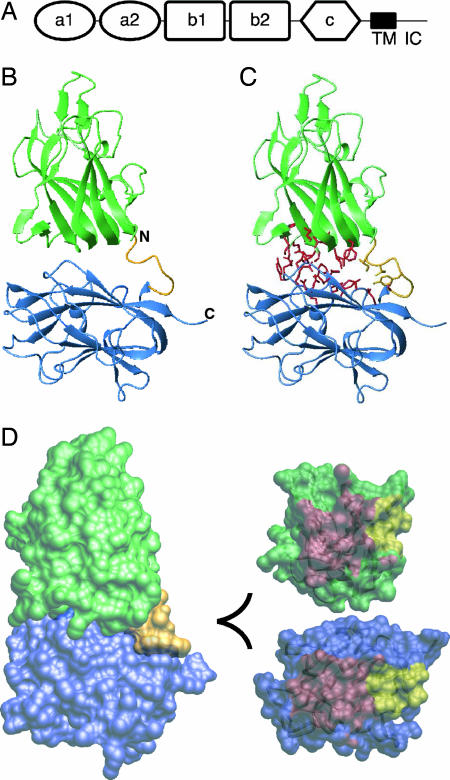

Fig. 1.

Structure of the b1b2 fragment of Nrp-1. (A) Domain organization of Nrp with the CUB domains (a1 and a2), coagulation factor domains (b1 and b2), MAM domain (c), transmembrane helix (TM), and intracellular domain (IC) indicated. (B) Ribbon diagram of b1 and b2 domains (green and blue, respectively) with the linker shown in gold. (C) Ribbon diagram of N1b1b2 with residues contributing to the b1b2 interface from b1 (333, 335, 362–368, 370, and 399–401) and b2 (464, 465, 468, 499, 501, 545–551, 577, and 581) shown in red and the linker region (residues 426, 427, 429, and 432) shown in gold. (D) (Left) Surface representation of the N1b1b2 colored as in A. (Upper Right) The interaction surface of the core b1 domain from the perspective of b2 with the core b1/b2 contact surface in red and linker contact surface in yellow. (Lower Right) The interaction surface of b2 as in D Upper Right.

VEGF-A, the prototypical member of the VEGF family, exists in a number of alternative splice forms that vary primarily in the length of C-terminal sequences, with VEGF165 representing the major angiogenic signaling molecule (reviewed in ref. 27). VEGF165 contains a cystine knot dimer, which interacts directly with VEGFR, as well as a positively charged HBD, which interacts with both heparin and Nrp (3, 28). Both VEGF165 and Nrp bind heparin/heparan sulfate, and heparin enhances the interaction between Nrp and VEGF from Kd = 2 μM in the absence of heparin to Kd = 25 nM in the presence of heparin (24, 29, 30). It remains unclear whether this effect is due simply to independent tethering of the two proteins or to some more specific role. The structure of the Nrp b1 domain has been determined and exhibits a typical coagulation factor fold (22). Based on the structure and the location of ligand binding sites in related coagulation factor and bacterial sialidase discoidin domains, it was hypothesized that a polar region encompassing specific b1 domain loops might be responsible for ligand binding (22, 31, 32).

We present here crystal structures of N1b1b2 both alone and complexed with the VEGF HBD analog Tuftsin. In addition, structural analysis combined with site-directed mutagenesis is used to identify the region on N1b1b2 responsible for heparin binding and also demonstrate heparin's role in dimerization of N1b1b2. Characterization of interactions between N1b1b2 and its ligands defines essential features of Nrp signaling complexes and provides a molecular basis for understanding Nrp function.

Results

Structure of the b1b2 Tandem Domain of Nrp.

The structure of N1b1b2 has been determined by x-ray crystallography (Fig. 1B). Both b1 and b2 domains are coagulation factor domain family members most closely related to the eukaryotic factor V/VIII family membrane adhesion domains (31). The individual domains possess the typical discoidin family β-sandwich fold characterized by three- and five-strand β-sheets and three extended loops or spikes on one end of the β-sandwich. The b1 and b2 domains show different levels of structural homology to factor V/VIII coagulation domains with a 1.2-Å rmsd over 153 residues for b1 and a 2.3-Å rmsd over 151 residues for b2 when compared with the C2 domain of factor VIII (33) [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6].

A striking feature of the N1b1b2 structure is an extensive interdomain interface that results in a fixed orientation between the two domains. This interface buries ≈1,360 Å2 of surface area and is composed of loops connecting strands 2-3, 4-5, and 6-7 on b1 and strands S3, S6, and S8 on the face of the three-strand β-sheet on b2 (Fig. 1 C and D). Additionally, the conserved six residue interdomain linker is well ordered and contributes ≈350 Å2 buried surface area to the interdomain interface (Fig. 1C). The interfacial residues are predominantly hydrophobic (Fig. 1 C and D), and 29/31 are conserved in all Nrp-1 and Nrp-2 homologs, indicating that this interdomain orientation is likely a general feature of the Nrp family.

Cocrystal of Tuftsin Bound to N1b1b2.

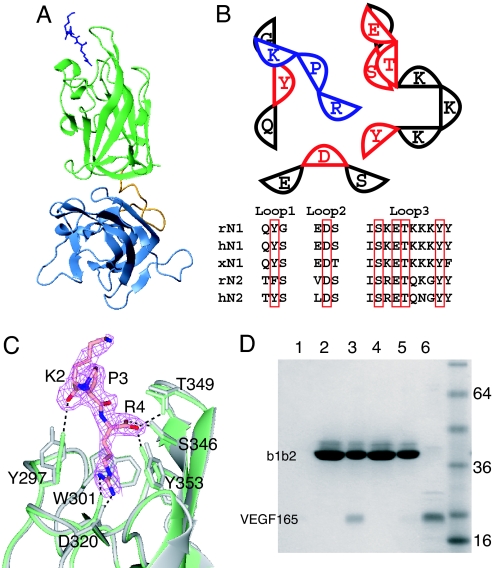

The coagulation factor domains of Nrp are responsible for binding basic regions of both VEGF and semaphorin (24, 25). Additionally, peptide inhibitors of Nrp are currently in development for use as antiangiogenic agents, all of which are basic in character and function by competing for ligand binding (18, 34–36). Tuftsin, an immunostimulatory tetrapeptide (TKPR), is very similar to the VEGF165 C terminus (DKPRR) and competes with VEGF165 for Nrp binding (34). A cocrystal of N1b1b2 bound to Tuftsin was determined and reveals that Tuftsin binds between the conserved interstrand loops at the tip of the b1 domain (Fig. 2A and B). This region corresponds to the ligand binding loops of coagulation factor and bacterial sialidase discoidin domains (31, 32). The C-terminal arginine (R4) of Tuftsin contributes the majority of interactions with N1b1b2 (Fig. 2 B and C). The aliphatic portion of R4 is stacked between the side chains of Y297 from the first ligand binding loop and Y353, and the guanidino group forms a salt bridge with D320 from the second ligand binding loop. The C terminus of Tuftsin interacts with the third ligand binding loop, with specific interactions with residues S346, T349, and Y353. The importance of a C-terminal arginine for interactions with Nrp at this site explains the observation that chemical alteration of the C terminus of inhibitory peptides to a carboxyamide results in complete loss of inhibition (36). Additionally, placental growth factor-2, which binds N1b1b2, also possesses a C-terminal arginine (24, 37). Indeed, with the numerous observed specific contacts, this region of the protein appears to be ideally suited to bind a C-terminal arginine. The backbone carbonyl of K2 also forms a hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group of Y297 (Fig. 2C). All of these Nrp residues are strictly conserved in Nrp-1 and Nrp-2 family members (Fig. 2B). When comparing the N1b1b2 structures determined in the presence and absence of Tuftsin, the backbone remains largely unchanged, but shifts are seen in the side chains of D320, Y297, and Y353, all of which directly contact Tuftsin (Fig. 2C). These residues move toward R4 of Tuftsin, contacting it along the full extent of the side chain.

Fig. 2.

Location of the VEGF binding site on N1b1b2. (A) Ribbon diagram of N1b1b2/Tuftsin complex with N1b1b2 colored as in Fig. 1A and Tuftsin shown as blue sticks. (B) Schematic of the interaction between N1b1b2 (red and black) and Tuftsin (blue). The three ligand binding loops form the ligand binding surface on Nrp. The residues directly contacting Tuftsin (red) are conserved in Nrp-1 and Nrp-2, as shown in the sequence alignment among rat, human, and Xenopus Nrps (r, h, and x, respectively). (C) Atomic detail of the interaction between N1b1b2 (green) and Tuftsin shown with the 2Fo − Fc electron density map (pink) contoured at 0.9 σ. Hydrogen bonds between Tuftsin and N1b1b2 are indicated, and the structure of N1b1b2 in the absence of Tuftsin is shown in gray. (D) Mutation of Tuftsin-interacting residues in N1b1b2 (S346A, E348A, T349A) knocks out the ability of His-tagged N1b1b2 to pull down VEGF165 by using an immobilized metal affinity column. Shown are VEGF binding to resin alone (lane 1), wild-type N1b1b2 load (lane 2), wild-type N1b1b2 elute (lane 3), mutant N1b1b2 load (lane 4), mutant N1b1b2 elute (lane 5), and 50% VEGF165 load (lane 6).

Tuftsin and VEGF compete for an overlapping binding site and are identical at three of the four amino acids (KPR). To confirm that the residue-specific contributions observed at the N1b1b2/Tuftsin interface are essential for VEGF165 binding, specific mutations were made to the loop 3 residues that contact Tuftsin. A triple-mutant N1b1b2 (S346A, E348A, T349A) was constructed and assayed in vitro for VEGF165 binding. Compared with the robust interaction of VEGF165 with wild-type N1b1b2, the mutant N1b1b2 lost the ability to bind VEGF165 (Fig. 2D, lane 3 vs. lane 5). Thus, the specific residues involved in Tuftsin binding are also required for VEGF binding.

A notable difference between Tuftsin and both VEGF165 (DKPRR) and PlGF-2 (AVPRR) is the presence of a diarginine motif at the C termini of VEGF165 and PlGF-2. Examination of the complex of N1b1b2 and Tuftsin shows that E348, which is strictly conserved in Nrps, is well positioned to interact with the side chain of the inserted arginine and yet maintain the observed carboxy-arginine binding (Fig. 2B). Curiously, the semaphorin basic tail (RAPRSV), which contains a sequence similar to Tuftsin and VEGF and competes with VEGF for binding, does not possess a C-terminal arginine. Thus, although the Nrp binding sites for the different ligands and peptides overlap, the precise arrangements of the ligands likely vary. Structural studies of both Nrp-1 and Nrp-2 bound to different ligands and peptides will be required to fully define the molecular basis for the varying affinities and specificities of Nrp for its targets.

Heparin Binding Promotes Dimerization of N1b1b2.

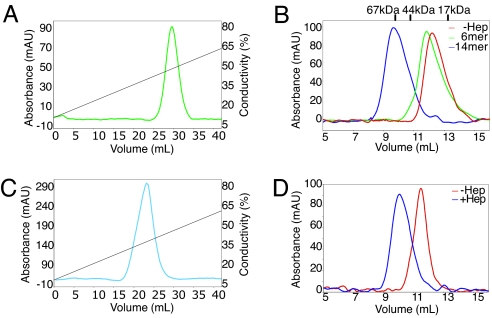

Heparin binds to both Nrp and VEGF165 and enhances the interaction of Nrp and VEGF165 by ≈20- to 100-fold (15, 24, 30). To better understand the role of heparin/heparan binding, the interaction of N1b1b2 with heparin was examined. We observe that N1b1b2 binds to a heparin-affinity column as previously shown (Fig. 3A; ref. 24) but also observe that addition of a heparin tetradecasaccharide (14-mer) leads to the near quantitative conversion of Npnb1b2 from a monomer (molecular massApp = 27 kDa, molecular massexp = 35 kDa) to a dimer (molecular massApp = 75 kDa, molecular massexp = 76 kDa) as judged by gel filtration (Fig. 3B). In contrast, incubation with a heparin hexasaccharide (6-mer) produces only a slight shift in elution time, consistent with an interaction between Nrp and heparin but not dimer formation (Fig. 3B). N1b1b2 dimerization thus requires a minimal heparin size. The observed N1b1b2 dimerization does not appear to result from nonspecific tethering as the addition of excess heparin does not disrupt dimer formation. Indeed, at substoichiometric amounts of heparin relative to N1b1b2, both monomeric and dimeric N1b1b2 species are observed with no intermediate species (SI Fig. 7). The need for a stoichiometric excess of heparin to observe complete N1b1b2 dimer formation indicates that a 2:2 ratio of Nrp:heparin is the most likely stoichiometry of the dimeric complex, but attempts to determine the stoichiometry more precisely have so far proven inconclusive. Heparin-mediated dimerization represents a general feature of Nrp as the b1b2 fragment of Nrp-2 (N2b1b2) also binds heparin and dimerizes in the presence of heparin (Fig. 3 C and D). Similar heparin-mediated dimerization has been extensively characterized in the FGF and FGF receptor system (38, 39).

Fig. 3.

Heparin (Hep) binds and induces dimerization of N1b1b2. (A) N1b1b2 binds to heparin Sepharose, eluting in ≈500 mM NaCl. (B) Size-exclusion chromatography of N1b1b2 reveals that heparin binding induces apparent dimerization of N1b1b2. This dimerization requires a length of heparin >6-mer. (C) Neuropilin-2, N2b1b2, also binds heparin Sepharose, eluting in ≈400 mM NaCl. (D) Heparin induces dimerization of Nrp-2 in a similar fashion to that of Nrp-1.

Identification of the Heparin Interaction Surface.

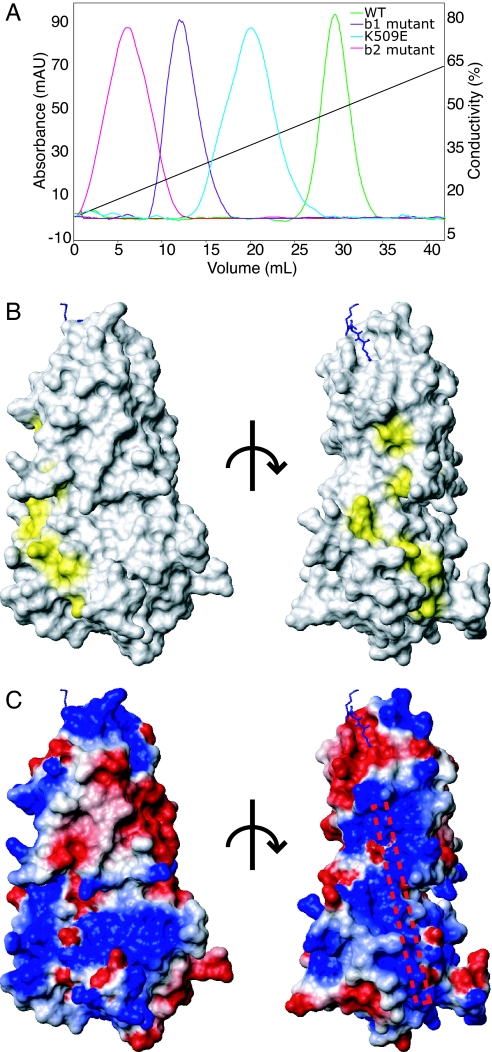

To investigate the mechanism of heparin-stimulated signaling in the Nrp system, we sought to define the heparin binding site on Nrp. One region of N1b1b2 has previously been found to be involved in Nrp- mediated cell adhesion (40). This cell adhesion site was mapped to a region on b2 containing residues 504–521 that contains a conserved BBXB motif, 513-516-RKFK−, which corresponds to a consensus heparin binding sequence in a β-strand (41). When these three basic residues are mutated to glutamate, a significant decrease in heparin binding is seen (Fig. 4A). Independent mutation of a nearby lysine (K509E) also decreased heparin binding, albeit to a lesser extent, indicating that the heparin interacts with an extended region (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

The tertiary structure of N1b1b2 domains creates a single heparin binding surface. (A) Heparin Sepharose binding of b1b2 mutants, which maps the surface involved in heparin binding. (B) Surface mapping of the residues identified as important for heparin binding using the orientation used in Fig. 1D (Left) and a 90° rotation about a vertical axis (Right). (C) Electrostatic surface map of N1b1b2 in the same orientations shown in B with a schematic rod marking the position of the heparin binding surface based on the observed electropositive surface patch and mutagenesis.

A homologous region of b1, residues 347–364, was also implicated in cell adhesion (40), and lysine residues 347 and 350–352 found in the third ligand binding loop were hypothesized to be responsible for the cell adhesion observed for the b1 peptide (22). These residues are not conserved, however, and their mutation does not affect heparin binding (Fig. 2B and data not shown). R359 and K373 are conserved basic residues on strand four of b1 adjacent to the identified cell adhesion region of b2. In contrast to the previous b1 mutations, mutation of these residues to glutamate significantly decreases heparin binding (Fig. 4A). When the b1 and b2 mutant sets are combined (R359E, K373E, R513E, K514E, K516E), heparin binding and heparin-mediated dimerization are lost (data not shown). When these residues are mapped on the surface of N1b1b2, they define a continuous electropositive region that appears well suited for heparin binding (Fig. 4 B and C). This strip is formed by residues from both b1 and b2 domains and is ≈40 Å in length, which would correspond to a heparin oligomer of ≈12 saccharides. Thus, the fixed domain arrangement observed for the N1b1b2 tandem domains composes the surface required for heparin binding. This heparin binding region is situated in close proximity to the Tuftsin binding site (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

From our data we are able to construct a model of interactions at the core of the Nrp signaling complex (Fig. 5). The N1b1b2 domain exists as an integral structural unit and binds its basic ligands and peptide mimics via the b1 domain interstrand loops. Heparin binding requires a combined surface created by the N1b1b2 tandem domain and induces specific dimerization of N1b1b2. This ligand and heparin bound Nrp dimer thus represents an active Nrp complex, which is then poised to activate its downstream receptors.

Fig. 5.

Structural model of Nrp representing the interactions at the core of the ligand binding interface. The HBD of VEGF165 directly interacts with the b1 domain via the terminal residues, encoded by exon 8, and also couples heparin and Nrp binding.

It has been widely assumed that the Nrp binding site on VEGF must reside in the region encoded by exon 7, residues 116–159 of VEGF165, because the presence of this region distinguishes VEGF121 and VEGF165 isoforms, only the latter of which binds Nrp (42). This isoform specificity is maintained by N1b1b2 (SI Fig. 8). In contrast, recent data suggest that the region encoded by exon 8, residues 160–165 of VEGF165, represents the site of direct interaction between VEGF165 and Nrp. An alternate splice form of VEGF, VEGF165b, differs only in the sequence of the final six residues owing to switching of exon 8 with exon 9. VEGF165b contains all of exon 7, but does not interact with Nrp and shows dramatically reduced angiogenic potential (43). In particular, VEGF165b has a C-terminal Asp in contrast to the critical C-terminal Arg of VEGF165 (44) (Fig. 2). It was further shown that a peptide corresponding to the exon 8 encoded region effectively blocked VEGF165 binding to Nrp expressing cells (36). Our data strongly support that it is the C-terminal tail encoded by exon 8 that is the site of direct interaction between VEGF165 and Nrp and provides a structural basis for this interaction (Fig. 2).

At least two factors likely contribute to the critical role of exon 7, which encodes most of the HBD of VEGF and is required for heparin binding (45, 46). Firstly, the region encoded by exon 7 may be required to extend the C-terminal Nrp-binding region from the VEGF cystine knot sufficiently to allow unencumbered access to the Nrp dimer. Secondly, the region encoded by exon 7 provides coupling between heparin and Nrp binding. Whereas a 12-mer fragment of heparin is required for efficient Nrp heparin binding and a 6- to 7-mer is required for efficient VEGF heparin binding, a 22-mer of heparin is required to promote optimal interaction of VEGF and Nrp (24, 47). Our results are consistent with a model of the Nrp-VEGF165 complex that creates a continuous heparin binding surface (Fig. 5). The heparin binding region on N1b1b2 is oriented in such a manner that the heparin polymer could extend to interact directly with the HBD of VEGF165. The ligand bound heparin-induced dimer of N1b1b2 likely works in concert with the MAM domain in orienting Nrp to activate either VEGFR or plexin receptors. According to this model, the recent finding that Nrp-1 itself can be heparan-sulfate modified on a serine between the b2 and MAM domains suggests a self-organized active Nrp species (48).

These structural studies represent an important step toward understanding mechanisms for Nrp's action in both angiogenesis and axon guidance by defining the basis for binding of both basic ligands and heparin. Additionally, these insights are directly applicable to the continued design and optimization of peptide inhibitors of Nrp function. Further studies are required to understand the basis for coupling of Nrp-mediated signaling to the activity of its partner receptors in the VEGFR and plexin families.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Rat N1b1b2 (273–585) and mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli strain Rosetta-gami-2 (Novagen, Madison, WI) as a His-tag fusion in pET28b (Novagen) or its derivative pT7HMT (49). Human N2b1b2 (276–595) in pET28b was expressed similarly. Cells were grown in Terrific-Broth at 37°C to an OD600 = 1.2 and after 15 min at 4°C induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside. After growth at 16°C for 16 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation, lysed, and centrifuged, and proteins were purified over HIS-Select (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) nickel affinity resin in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 400 mM NaCl with an imidazole gradient from 25–500 mM.

For crystallization, N1b1b2 was purified by gel filtration by using a Superdex75 HiLoad 16/60 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated and run using buffer A (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5/75 mM NaCl). Analytical gel filtration experiments were performed by using a Superdex 75 10/16 column (GE Healthcare) in buffer A. Calibration standards used were BSA, ovalbumin, myoglobin, and vitamin B12 (Bio-Rad). The heparin bound form of N1b1b2 had a higher absorbance than apo protein, and spectra were scaled by a factor of ≈1.7.

Heparin binding was performed by using a 5-ml HiTrap Heparin HP column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) with a linear gradient of 150–600 mM NaCl.

VEGF165 and VEGF121 were produced as an untagged protein in pET3a (Novagen) and expressed in inclusion bodies. Protein was solubilized and refolded according to established procedures (50). Refolded VEGF165 was purified by heparin affinity as above but with a linear gradient of 150 mM to 1 M NaCl and eluted at ≈700 mM NaCl. Correctly refolded VEGF165 was confirmed by the presence of a disulfide-linked dimer on nonreducing SDS/PAGE gel and binding to heparin sulfate with the expected affinity. Proteins were concentrated and buffer exchanged to 75 mM NaCl before subsequent experiments.

VEGF Pull-Down.

Purified wild-type or variant N1b1b2 (0.2 mg) bound to 75 μl of HIS-Select resin were incubated with 0.1 mg of VEGF for 30 min at 4°C in buffer A with 50 mM imidazole. Resin was washed three times with 0.75 ml of buffer A containing increasing imidazole (50, 60, and 70 mM). Bound protein was then eluted by using 0.1 ml of buffer A containing 300 mM imidazole.

Crystallization.

Crystals of N1b1b2 were prepared in hanging-drop vapor-diffusion experiments with protein concentrations of 3 mg/ml. Single high-quality crystals were obtained in 2–3 weeks from a 1:1 mixture of protein to mother liquor containing 100 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 10% PEG 20000, and 7% ethylene glycol incubated at 18°C. Crystals were passed through mineral oil and flash frozen, and diffraction data were collected to 2.4 Å Bragg spacings (SI Table 1). A different crystal form was obtained when crystallizing the protein in complex with Tuftsin (Bachem, Torrance, CA) and a 14-mer of heparin (Neoparin, Alameda, CA). Single high-quality crystals were obtained in a 1:4:1.5 protein:Tuftsin:heparin mixture. Crystals formed in 1–2 weeks from a 1:1 mixture of protein to mother liquor containing 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 6.0), 15% PEG 4000, and 0.1 M MgCl2 (Sigma–Aldrich). Diffraction data were collected to 2.15 Å Bragg spacings (SI Table 1). Electron density for the Tuftsin peptide was readily observable. Heparin induced dimerization was found to be sensitive to ionic strength in solution, and under these conditions heparin density was not observed.

Crystal Structure Determination and Analysis.

Diffraction data were collected on the Gulf Coast Protein Crystallography Consortium beamline at the Center for Advanced Microstructures and Devices. The data were processed by using HKL2000 (51). A molecular replacement solution using the Nrp-1 b1 domain (PDB ID code 1KEX) was obtained for both b1 and b2 domains by using the program MOLREP in the CCP4 suite (52, 53). After initial simulated annealing in CNS (54) and rebuilding using RESOLVE (55), model rebuilding and refinement were accomplished with iterative rounds of building and refinement by using COOT (56) and REFMAC5 (57), respectively. TLS groups for use in refinement were derived from TLSMD (58). The refined N1b1b2 structure was used as a molecular replacement model for the Tuftsin bound cocrystal, and refinement was performed as above. Diffraction data and final refinement statistics are summarized in SI Table 1.

Structural alignment was performed by using the DALI server (www.ebi.ac.uk/dali) (59). Dimer interfaces were analyzed by using the Protein–Protein interaction server (www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/bsm/PP/server). Molecular graphics were prepared by using MOLMOL (60), CCP4 mg (61), and Dino (www.dino3d.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Ginty and Jason McLellan for helpful discussions and Dr. Carl Vander Kooi for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA90466, a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Fellowship (to C.W.V.K.), the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Cancer Research Foundation (B.P.), the State of Louisiana, the Louisiana Governor's Biotechnology Initiative (H.D.B.), and the Gulf Coast Protein Crystallography Consortium (D.B.N.).

Abbreviations

- Nrp

neuropilin

- VEGFR

VEGF receptor

- N1b1b2

tandem b1 and b2 domains of Nrp-1

- HBD

heparin-binding domain.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 2ORX and 2ORZ).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0700043104/DC1.

References

- 1.Kolodkin AL, Levengood DV, Rowe EG, Tai YT, Giger RJ, Ginty DD. Cell. 1997;90:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He Z, Tessier-Lavigne M. Cell. 1997;90:739–751. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soker S, Takashima S, Miao HQ, Neufeld G, Klagsbrun M. Cell. 1998;92:735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klagsbrun M, Takashima S, Mamluk R. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;515:33–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0119-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi T, Fournier A, Nakamura F, Wang LH, Murakami Y, Kalb RG, Fujisawa H, Strittmatter SM. Cell. 1999;99:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai H, Reed RR. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6519–6527. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06519.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellani V, Chedotal A, Schachner M, Faivre-Sarrailh C, Rougon G. Neuron. 2000;27:237–249. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellani V, De Angelis E, Kenwrick S, Rougon G. EMBO J. 2002;21:6348–6357. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guttmann-Raviv N, Kessler O, Shraga-Heled N, Lange T, Herzog Y, Neufeld G. Cancer Lett. 2006;231:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bielenberg DR, Pettaway CA, Takashima S, Klagsbrun M. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis LM. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1099–1107. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee SK, Zoubine MN, Tran TM, Weston AP, Campbell DR. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:253–260. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latil A, Bieche I, Pesche S, Valeri A, Fournier G, Cussenot O, Lidereau R. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:167–171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000320)89:2<167::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephenson JM, Banerjee S, Saxena NK, Cherian R, Banerjee SK. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:409–414. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parikh AA, Fan F, Liu WB, Ahmad SA, Stoeltzing O, Reinmuth N, Bielenberg D, Bucana CD, Klagsbrun M, Ellis LM. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:2139–2151. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagnon ML, Bielenberg DR, Gechtman Z, Miao HQ, Takashima S, Soker S, Klagsbrun M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2573–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040337597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barr MP, Byrne AM, Duffy AM, Condron CM, Devocelle M, Harriott P, Bouchier-Hayes DJ, Harmey JH. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:328–333. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starzec A, Vassy R, Martin A, Lecouvey M, Di Benedetto M, Crepin M, Perret GY. Life Sci. 2006;79:2370–2381. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vacca A, Scavelli C, Serini G, Di Pietro G, Cirulli T, Merchionne F, Ribatti D, Bussolino F, Guidolin D, Piaggio G, et al. Blood. 2006;108:1661–1667. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreuter M, Woelke K, Bieker R, Schliemann C, Steins M, Buechner T, Berdel WE, Mesters RM. Leukemia. 2006;20:1950–1954. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takagi S, Hirata T, Agata K, Mochii M, Eguchi G, Fujisawa H. Neuron. 1991;7:295–307. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CC, Kreusch A, McMullan D, Ng K, Spraggon G. Structure (London) 2003;11:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu C, Limberg BJ, Whitaker GB, Perman B, Leahy DJ, Rosenbaum JS, Ginty DD, Kolodkin AL. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18069–18076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamluk R, Gechtman Z, Kutcher ME, Gasiunas N, Gallagher J, Klagsbrun M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24818–24825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giger RJ, Urquhart ER, Gillespie SK, Levengood DV, Ginty DD, Kolodkin AL. Neuron. 1998;21:1079–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H, He Z, Bagri A, Tessier-Lavigne M. Neuron. 1998;21:1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiesmann C, Fuh G, Christinger HW, Eigenbrot C, Wells JA, de Vos AM. Cell. 1997;91:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N. Science. 1989;246:1306–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.2479986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuh G, Garcia KC, de Vos AM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26690–26695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuentes-Prior P, Fujikawa K, Pratt KP. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2002;3:313–339. doi: 10.2174/1389203023380639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaskell A, Crennell S, Taylor G. Structure (London) 1995;3:1197–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pratt KP, Shen BW, Takeshima K, Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Stoddard BL. Nature. 1999;402:439–442. doi: 10.1038/46601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Wronski MA, Raju N, Pillai R, Bogdan NJ, Marinelli ER, Nanjappan P, Ramalingam K, Arunachalam T, Eaton S, Linder KE, et al. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5702–5710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giordano RJ, Anobom CD, Cardo-Vila M, Kalil J, Valente AP, Pasqualini R, Almeida FC, Arap W. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia H, Bagherzadeh A, Hartzoulakis B, Jarvis A, Lohr M, Shaikh S, Aqil R, Cheng L, Tickner M, Esposito D, et al. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13493–13502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Migdal M, Huppertz B, Tessler S, Comforti A, Shibuya M, Reich R, Baumann H, Neufeld G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22272–22278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DiGabriele AD, Lax I, Chen DI, Svahn CM, Jaye M, Schlessinger J, Hendrickson WA. Nature. 1998;393:812–817. doi: 10.1038/31741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, Eliseenkova AV, Yeh BK, Yayon A, Linhardt RJ, Mohammadi M. Mol Cell. 2000;6:743–750. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu M, Murakami Y, Suto F, Fujisawa H. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1283–1293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cardin AD, Weintraub HJ. Arteriosclerosis (Dallas) 1989;9:21–32. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soker S, Gollamudi-Payne S, Fidder H, Charmahelli H, Klagsbrun M. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31582–31588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cebe Suarez S, Pieren M, Cariolato L, Arn S, Hoffmann U, Bogucki A, Manlius C, Wood J, Ballmer-Hofer K. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2067–2077. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6254-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D, Harper SJ. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4123–4131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keyt BA, Berleau LT, Nguyen HV, Chen H, Heinsohn H, Vandlen R, Ferrara N. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7788–7795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fairbrother WJ, Champe MA, Christinger HW, Keyt BA, Starovasnik MA. Structure (London) 1998;6:637–648. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson CJ, Mulloy B, Gallagher JT, Stringer SE. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1731–1740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shintani Y, Takashima S, Asano Y, Kato H, Liao Y, Yamazaki S, Tsukamoto O, Seguchi O, Yamamoto H, Fukushima T, et al. EMBO J. 2006;25:3045–3055. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geisbrecht BV, Bouyain S, Pop M. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;46:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christinger HW, Muller YA, Berleau LT, Keyt BA, Cunningham BC, Ferrara N, de Vos AM. Proteins. 1996;26:353–357. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199611)26:3<353::AID-PROT9>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. J Appl Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collaborative Computational Project N. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54(Pt 5):905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terwilliger T. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2004;11:49–52. doi: 10.1107/s0909049503023938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murshudov GN. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Painter J, Merritt EA. Acta Crystallogr D. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holm L, Sander C. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:653–662. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Potterton L, McNicholas S, Krissinel E, Gruber J, Cowtan K, Emsley P, Murshudov GN, Cohen S, Perrakis A, Noble M. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2288–2294. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.