Abstract

p38 MAPK and MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) are key components of signaling pathways leading to many cellular responses, notably the proinflammatory cytokine production. The physical association of p38α isoform and MK2 is believed to be physiologically important for this signaling. We report the 2.7-Å resolution crystal structure of the unphosphorylated complex between p38α and MK2. These protein kinases bind “head-to-head,” present their respective active sites on approximately the same side of the heterodimer, and form extensive intermolecular interactions. Among these interactions, the MK2 Ile-366–Ala-390, which includes the bipartite nuclear localization signal, binds to the p38α-docking region. This binding supports the involvement of noncatalytic regions to the tight binding of the MK2:p38α binary assembly. The MK2 residues 345–365, containing the nuclear export signal, block access to the p38α active site. Some regulatory phosphorylation regions of both protein kinases engage in multiple interactions with one another in this complex. This structure gives new insights into the regulation of the protein kinases p38α and MK2, aids in the better understanding of their known cellular and biochemical studies, and provides a basis for understanding other regulatory protein–protein interactions involving signal transduction proteins.

Keywords: X-ray structure

The MAPK has been directly associated with proinflammatory cytokine production. Inhibition of p38α (and its homolog, p38β) by inhibitors such as SB203580 and BIRB 796, reduces LPS-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and IL-1, that are implicated in the etiology of chronic inflammation (1–5). Recent genetic evidence suggests that p38α, not p38β, is the major p38 isoform involved in the LPS-induced immune response (6). Embryonic stem cells derived from mice that lack the p38α function exhibit impaired IL-1 signaling (7). Biological therapies directed against inflammatory cytokines, e.g., anti-TNFα and anti-IL-1β, have also proven effective at ameliorating the symptoms of inflammatory diseases such as arthritis and psoriasis (not anti-IL-1β-mediated) (8–11).

MAPK-activated protein kinase-2 (MK2), the primary substrate of p38α, is also a key participant in modulating proinflammatory cytokine production (12, 13). MK2 knockout mice (MK2−/−) challenged with LPS produce significantly less TNFα, IL-6, IFNγ, and IL-1 than LPS-stimulated wild-type mice (13). MK2−/− mice are also resistant to collagen-induced arthritis (14). The transfection of cultured keratinocytes with MK2-specific small interfering RNA led to a significant decrease in MK2 protein expression and a subsequent, significant reduction in the production of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 (15). The catalytic activity of MK2 has further been shown to be necessary for TNFα production (16). Taken together, these data suggest that the inhibition of the p38α pathway, particularly MK2, is desirable for the potential treatment of chronic inflammation.

In resting cells, p38α forms a physiological complex with MK2, which is located in the nucleus (17, 18). Upon activation, p38α activates MK2 by phosphorylating Thr-222′, Ser-272′, and Thr-334′ (19). The phosphorylation of MK2 at Thr-334′ is associated with the enablement of the MK2 nuclear export signal (NES) (17, 20, 21), thus leading to the MK2:p38α translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (18, 22). Cytoplasmic, active MK2 then phosphorylates downstream targets such as the heat-shock protein HSP27 and tristetraprolin (TTP), leading to cellular response (23–25).

The complex between MK2 and p38α is of relatively high affinity, with Kd = 2.5 nM (26). Recent data suggest that this affinity may be as high as 0.5 nM (27). Evidence suggests that the MK2 C-terminal region is the key contributor to this interaction (26, 28). The MK2 C-terminal region has a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS), an NES, and a p38α-docking domain (17, 29, 30). A peptide corresponding to MK2 370′–400′ binds to p38α with a Kd of 8–20 nM and blocks phosphorylation of MK2 with an IC50 of 60 nM (26). Evidence suggests that p38α has a docking D motif that is a key feature for the interaction with its high-affinity substrates and activating enzymes. Site-directed mutagenesis suggests that the p38α-docking area involves a glutamate–aspartate (ED) site and a common docking (CD) domain (31, 32). Furthermore, the crystal structure of p38α complexed with short docking peptides show that these peptides bind in a hydrophobic docking groove flanked by the ED site and Asn-115–Asp-125, but do not involve the CD domain (33). From these studies, it is unclear how to infer both the specific MK2 mode of binding to the CD domain of p38α and the specific interactions that could involve this region in such a complex. It is also unknown whether other regions are involved in the interactions between MK2 and p38α.

Herein we describe the crystal structure of the heterodimeric MK2:p38α. The formation of such a complex has been shown to be physiologically relevant in refs. 17 and 18. Our detailed structure of the MK2:p38α complex provides a framework to better understand the specifics of binding between these two proteins together.

Results and Discussion

Structure Determination.

The structure of the binary complex of unphosphorylated recombinant MK2 bound to unphosphorylated recombinant p38α has been solved by molecular replacement and refined to 2.7-Å resolution [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. The final model of the heterodimer has an Rfactor of 23.9% (Rfree of 29.6%) and reasonable stereochemistry (Table 1). It includes 332 MK2 residues, 340 p38α residues, and 60 ordered water molecules. Of the N and C termini of both proteins, 5–10 residues are disordered. Part of the p38α activation loop and the MK2 phosphorylation region encompassing Ser-272′ are also disordered.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P41212 | |

| Cell dimensions, Å | a = b = 83.31, c= 231.49 | |

| Resolution, Å | 50–2.7 (2.8–2.7) | |

| Rsym | 0.12 (0.59) | |

| Average I/σI | 8.8 (2.1) | |

| Completeness, % | 98.0 (84.9) | |

| Redundancy | 7.6 (5.7) | |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 2.7 | |

| No. reflections* | 22,770 | |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.239/0.296 | |

| Non-H protein atoms | 5,443 | |

| Ordered non-H atoms | ||

| p38α MAPK | 6–172, 181–353 | |

| MK2 | 51′–269′, 278′–390′ | |

| Water molecules | 60 | |

| rmsd bond lengths, Å | 0.008 | |

| rmsd bond angles, ° | 1.09 | |

The highest resolution shells are shown in parentheses.

*Of these reflections, 5% are used for the Rfree calculation.

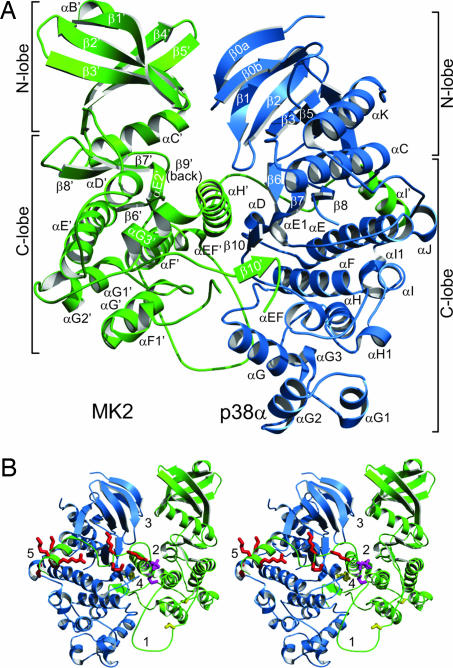

In the heterodimer crystal structure, each of the two globular proteins adopts the canonical protein kinase fold (Fig. 1A) observed with other protein kinases. Each has two lobes: a mostly β-stranded N-terminal small lobe (N-lobe), and a mostly α-helical C-terminal larger lobe (C-lobe). The two proteins bind head-to-head, such that the MK2 N-lobe interacts with the corresponding p38α N-lobe, and the MK2 C-lobe interacts with the corresponding p38α C-lobe. The C-lobes are offset by ≈10 Å relative to each other.

Fig. 1.

Structure of MK2:p38α. (A) The MK2 (green) and p38α (blue) secondary structures are shown as bundles for α-helices and arrows for β-strands. A prime (′) suffix is used to denote MK2 residues and secondary structure elements. (B) In this opposite view to A, the five intermolecular interface regions are identified with a number. The key regulatory element regions are also shown for the MK2 bipartite NLS (red), the MK2 NES (magenta), and the regulatory phosphorylation sites p38α Tyr-182 and MK2 Thr-222′ and Thr-334′ (yellow).

MK2:p38α Interface.

The interface between these two proteins consists of five discontinuous contact regions. As a result, the buried solvent-accessible surface area is ≈6,500 Å2. This area is more extensive than those of many other known protein–protein interfaces (34). The MK2 autoinhibitory domain (residues 345′–390′) contributes more than half of the buried surface area; the other half involves multiple regions of both proteins. All five discontinuous contact regions (Fig. 1B) are further described below.

MK2 activation segment Tyr-228′–Tyr-240′.

This segment (Fig. 1A) binds to the p38α surface but on the opposite side of both active sites. Its conformation is stabilized by H bonds with Val-273 and Arg-220 of p38α and by multiple van der Waals interactions (SI Fig. 7A). These interactions likely stabilize the observed conformation, because the MK2 activation segment is partially disordered in both the uncomplexed MK2 and the constitutively active MK2 structures (20, 35).

MK2 helix αH′ (Asp-345′–Val-365′).

The MK2 helix αH′ position is stabilized by multiple intermolecular H bonds and van der Waals contacts with p38α P loop (β1-β2), loop β3-αC, helix αD, and strand β10 (SI Fig. 7B). These elements are located at or near the p38α active site (Fig. 1A). There are two salt bridges, Asp-351′ and Glu-354′, to p38α Arg-57 and seven H-bonds: Glu-347′ to p38α Gln-60 and Ser-61; Glu-354′ to p38α Ala-34 and Ser-56; Glu-355′ to p38α Tyr-35; and Thr-362′ to p38α Asn-114 and Lys-118. As a result of these intermolecular interactions and multiple additional intramolecular interactions, only 30% of the helix αH′ surface is solvent-accessible. The location of αH′ limits access to MK2's substrate-binding site and blocks access to p38α's active site.

p38α loop β0a-β0b interaction to MK2 P loop β1′-β2′.

These two loops (SI Fig. 8) form two intermolecular backbone-backbone H bonds involving MK2 Gly-73′ and Ile-74′ with p38α Lys-15 and Asn-14, respectively, and multiple intermolecular van der Waals contacts (SI Fig. 8).

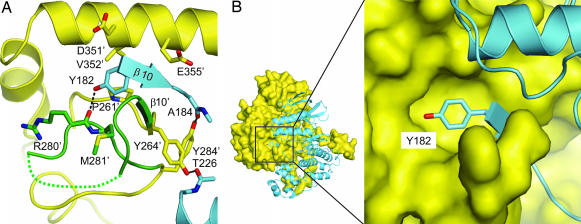

MK2 Tyr-264′–Tyr-284′, comprising a regulatory phosphorylation region, interacting with the p38α regulatory phosphorylation region.

This MK2 region (Fig. 2) is partly disordered between Ala-270′ and Thr-277′. The ordered portion is stabilized by H bonds, involving Tyr-264′ and Tyr-284′ with p38α Thr-226 and Ala-184, respectively (Fig. 2A), and by an intermolecular β-sheet. This intermolecular antiparallel β-sheet is formed by MK2 β10′ Tyr-264′–Ser-266′ and p38α β10 Gly-181–Val-183. Also located in this p38α region is the phosphorylation lip motif Thr–X–Tyr residue Tyr-182. Tyr-182 contributes to the heterodimeric interactions by binding to a previously unrecognized pocket on the MK2 C-lobe surface (Fig. 2B). In this pocket, Tyr-182 is stabilized by an H bond with the backbone of Arg-280′, an edge-to-face stacking with Phe-263′, and van der Waals interactions with Pro-261′, Tyr-264′, Arg-280′, Met-281′, Asp-351′, Val-352′, and Glu-355′. We speculate that phosphorylation of Tyr-182 would not be compatible with binding to this MK2 pocket and would thus increase the complex's propensity to unravel at the αH′ interface. Such an unraveling would allow other MK2 residues, such as Thr-222′, Ser-272′, and Thr-334′, to be presented to the p38α active site for phosphorylation.

Fig. 2.

Environment of the p38α (yellow and green) phosphorylation region interacting with MK2 (blue). (A) Intermolecular H bonds (black dashed line) in the vicinity of p38α Tyr-182 interaction with MK2. The intermolecular antiparallel plated β-sheet formed by β10 and β10′ is shown with two arrows. The MK2 region Ser-265′–Gln-283′ (green) is flanked by Tyr-264′ and Tyr-284′, both of which are involved in intermolecular H bonds with p38α. The MK2 phosphorylation region around Ser-272′ is unresolved and represented with the green dotted line. (B) The p38α phosphorylation lip Tyr-182 interacts in a MK2 surface pocket.

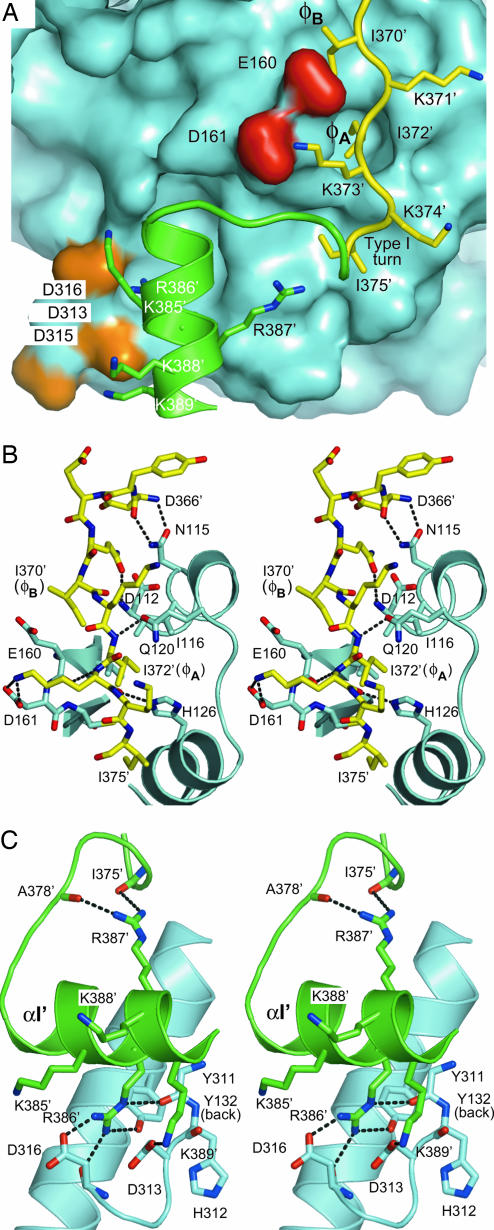

MK2 C-terminal region Asp-366′–Ala-390′.

MK2 Asp-366′–Asn-380′ (Fig. 3A) comprises two short extended structures joined by a type-I turn involving Lys-374′–Asp-377′. This turn accepts two intramolecular H bonds from Arg-387′. The segment Asp-366′–Asn-380′, which includes helix αI′ (Pro-381′–Ala-390′), interacts with p38α (Fig. 3B): Asp-366′ forms two H bonds with p38α Asn-115; Gln-369′ accepts an H bond from p38α Asp-112; Ile-372′ accepts an H bond from p38α Gln-120; Lys-373′ accepts an H bond from p38α His-126 and donates an H bond to p38α Glu-160; and Asn-380′ donates an H bond to p38α Asp-161. Lys-373′ also forms a solvent-exposed salt bridge with p38α Asp-161. Ile-372′ and Ile-375′ form hydrophobic interactions in a groove situated between loops αD-αE and β7-β8 of p38α. Near the MK2 C terminus, Pro-381′–Ala-390′ form the helix αI′ that interacts with p38α (Fig. 3C): Leu-382′ donates an H bond to p38α Glu-81; Arg-386′ forms H bonds with p38α Tyr-132 and Tyr-34 and a salt bridge with Asp-316; and Lys-389′ forms a salt bridge with Asp-313. Such extensive interactions suggest that the MK2 C-terminal region, Asp-366′–Ala-390′, significantly contributes to the overall affinity between MK2 and p38α.

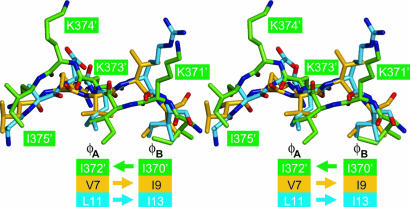

Fig. 3.

MK2 bipartite NLS interaction with p38α D motif docking. (A) Overview of the MK2 NLS interaction with the p38α docking region. The MK2 Ile-370′–Ala-390′ is shown in yellow for the NLS 371′-KIKK-375′ and in green for the NLS 385′-KRRKK-389′. p38α is represented with a cyan surface rendering, where the ED site carboxylate groups are colored red and the CD domain carboxylate groups are colored orange. The hydrophobic motif key residues φA and φB are noted adjacent to Ile-372′ and Ile-370′, respectively. (B) The MK2 first part NLS interaction to p38α hydrophobic docking groove. The hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are indicated by dashed lines. (C) The MK2 second part NLS interaction with p38α CD domain region.

p38α Conformation.

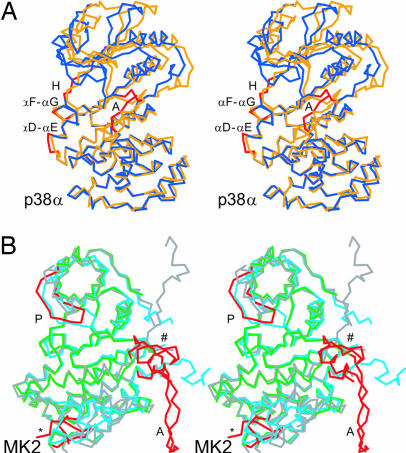

The structure of p38α in the present complex has some differences from the publicly available p38α monomeric structures. The p38α structure of the present heterodimer superimposes on the apo-p38α (36) with an rms deviation of 1.7 Å for all Cα atoms (Fig. 4A). This large rms deviation is partly explained by a 5° rigid rotation movement of the N-lobe, such that the ATP-binding site is slightly closed on itself in the heterodimer. The complex formation with MK2 induces other conformational changes in p38α. In one such change, the heterodimeric p38α activation loop adopts a different conformation than previously seen in the apo-p38α, and in the complexes with either the 3′-iodo-phenyl analogue of SB203580 or various BIRB 796-class inhibitors (3, 37). Here, the p38α activation segment extends away from the active site; its conformation is stabilized by direct contacts with MK2 through an intermolecular antiparallel β-sheet and by interactions of its regulatory phosphorylation site Tyr-182 with a pocket on the MK2 surface. MK2 binding to p38α also induces a small side-chain displacement of the hinge region Met-109, a rearrangement that is similar to but less pronounced than the myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2A peptide (pepMEF2A)-induced p38α changes (33). In another conformational change, p38α loop αD-αE is rearranged in the heterodimer, such that the Gln-120 amide side-chain group is moved by ≈10 Å and now interacts with MK2. Finally, in the complex with MK2, the p38α αF-αG loop is slightly displaced to form H bonds with the MK2 Tyr-226′ phenol. The different conformation of the p38α active site and its nearby environment has the potential to affect its function.

Fig. 4.

Heterodimer-induced conformational changes of MK2 and p38α. (A) Overlay of the uncomplexed p38α (orange) (36) with the p38α (blue) from MK2:p38α. Only the carbon–α-chain trace is shown on this stereoview. Areas of significant differences (red) are annotated for the hinge region at and around Met-109 (H) and for the activation loop (A). (B) Overlay of the uncomplexed inactive MK2 (i-mk2) (gray) (20), the uncomplexed partially active MK2 (a-mk2) (light blue) (35), and the MK2 (green) from MK2:p38α. As in A, only the carbon–α-trace is shown on this stereoview. The four noticeable conformational change regions (red) are annotated for the P loop (P), the regulatory phosphorylation region near Ser-272′ (∗), the activation loop (A), and the C-terminal docking region 370′–400′ (#).

MK2 Conformation.

The overlay of the heterodimeric MK2 with the uncomplexed unphosphorylated inactive apo-MK2 (i-MK2) (20) and with the uncomplexed, unphosphorylated, constitutively active MK2 (41′–364′) (35) (a-MK2) shows differences in four regions (Fig. 4B). First, the P-loop (Tyr-63′–Asn-83′) forms an α-helix in the i-MK2, but an antiparallel β-sheet in the a-MK2 and in the heterodimer where it interacts with p38α loop β1-β2. The biological relevance of the atypical P loop α-helical conformation in the i-MK2 is unclear. Second, the activation loop segment is disordered in both the i-MK2 and the a-MK2 but is ordered in the heterodimer where it adopts an extended conformation stabilized by interactions with p38α. Third, the regulatory phosphorylation region Tyr-264′–Tyr-284′ is mostly ordered in both the i-MK2 and the a-MK2, where it contains a two-turn α-helix. Although this region is also partly disordered in the heterodimer, it adopts a different conformation in which it interacts with the p38α activation segment, forming key intermolecular interactions (Fig. 2A). Fourth, the MK2 C-terminal region Asp-366′–Ala-390′ has a different conformation in the heterodimer than the i-MK2 (the residues 365′ to the C terminus are not present in a-MK2). The previously disordered region Pro-381′–Ala-390′ is well ordered in the heterodimer and forms the α-helix αI′. Among these differences, it appears that the P loop conformational change is the only one at or near the MK2 active site. Because of the expected mobility of this loop, it is unclear whether the MK2 P loop conformational change will affect the enzyme catalytic activity.

Docking Region.

The extensive interactions between MK2 and p38α are consistent with the known tight binding of these two proteins in the unphosphorylated form. MK2 (1′–400′) binds tightly to p38α with a Kd of 2.5 nM, but its shorter splice variant MK2B binds poorly to p38α with a Kd > 5 μM (26). Isolated MK2 peptide residues 370′–400′, which approximately represent the difference between MK2 and MK2B, also bind p38α tightly with a Kd of 20 nM (26). Furthermore, active p38α maintains a strong affinity for both inactive MK2 (Kd of 6.3 nM) and a-MK2 (Kd of 60 nM) (26). These binding numbers suggest that the MK2 C-terminal 31 residues are essential for tight binding with p38α. This MK2 C terminus is known as a docking region (32, 38).

A tight intermolecular interaction greatly facilitates MK2 activation by p38α (26), suggesting the involvement of noncatalytic regions as essential components of the MK2:p38α complex. The apparent second-order catalytic rate constant for MK2 activation by p38α is kcatapp = 0.049 s−1, whereas the catalytic rate constant of activation of the shorter MK2B is poorer (kcatapp ≈ 0.009 s−1). The successful phosphorylation of multiple sites on MK2, Thr-222′ and Ser-272′, and to some extent Thr-334′, suggests that the p38α active site is no longer significantly obstructed in its active form. Of the five interface regions of the MK2:p38α complex, only the MK2 docking region is neither a phosphorylation region nor a region interacting close to the p38α active site. This finding is in agreement with the involvement of the MK2 docking region as a main contributor to the tight binding of MK2:p38α.

The MK2 docking region has been previously proposed to form important functional interactions with the p38α docking D motif. The p38α docking D motif is formed by: a CD domain involving Asp-313, Asp-315, and Asp-316; a Glu-160–Asp-161 ED site; and a hydrophobic docking groove (31–33). The MK2 docking region includes an NLS sequence, which is comprised of a basic bipartite motif (R/K–R/K–X10–R/K–R/K–R/K–R/K–R/K) (39) embedded in Lys-373′–Lys-389′. In the present structure, the MK2 NLS-containing docking region Asp-366′–Ala-390′ forms extensive interactions with the p38α D motif (Fig. 3).

In the first part, 370′-IKIKKI-375′ of the MK2 NLS, the three lysines are solvent exposed (Fig. 3A). The side chain of Lys-373′ forms a salt bridge with the side chain of p38α Asp-161 (Fig. 3B). This direct interaction is consistent with a role of Glu-160–Asp-161 in docking-sequence specificity, as previously proposed on the basis of p38α mutants analysis (31). Such features may help maintain p38α specificity for MK2. In the cell, protein–protein interaction specificity helps reducing unnecessary crosstalk within and between signaling pathways (40).

The MK2 αI′, Pro-381′–Ala-390′, interacts with the p38α CD domain, where the Arg-386′ guanidium group forms a salt bridge with Asp-316 and H bonds with Tyr-311, Tyr-132, and Asp-316 (Fig. 3C). Such an interacting environment is similar to that seen in the ERK2-peptide-hematopoietic protein tyrosine phosphatase (pepHePTP) complex (41), in which HePTP Arg-21′ forms extensive interactions with ERK2 similarly to how MK2 Arg-386′ forms interactions with p38α. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that Arg and Asp residues are key partners in both p38α and ERK2 electrostatic docking with their respective protein partners (32).

Structural analyses of p38α with short docking sequences of the transcription factor MEF2A (pepMEF2A) and the activating enzyme MAPK kinase 3b (MKK3b) (pepMKK3b) have previously revealed a hydrophobic docking groove (33). This groove is located in the C-lobe and accommodates the binding of φA–X–φB motif-containing sequences, where φA and φB are hydrophobic residues. MK2 binds to this p38α hydrophobic grove in the opposite direction than pepMEF2A and pepMKK3b. An overlay of p38α complexed with MK2 and p38α complexed with the pepMEF2A and pepMKK3b peptides shows spatial conservation of the motif φA–X–φB (Fig. 5). MK2 Ile-370′ and Ile-372′ occupy the same binding pockets as residue φB and φA, respectively. Like pepMEF2A and pepMKK3b, MK2 also forms H bonds with p38α Gln-120, His-126, and Glu-160. Such conservation between the docking sequences binding in opposite directions suggests a previously unexpected p38α tolerance of its hydrophobic docking groove. Other known docking peptide complexes, such as ERK2-pep-hematopoietic protein tyrosine phosphatase (pepHePTP) and JNK1–JNK-interacting protein 1 peptide (pepJIP1), make use of an equivalent φA–X–φB docking groove binding motif (41, 42) in the same polypeptide direction as both pepMEF2A and pepMKK3b. Thus, the MK2 docking to p38α represents a previously unrecognized docking class.

Fig. 5.

Structural similarities of the heterodimer MK2 docking region and both the pepMEF2A and pepMKK3b. In this stereoview, the carbon atoms are indicated in green for MK2, in orange for pepMEF2A, and in light blue for pepMKK3b. The MK2 region binds p38α with the opposite orientation than pepMEF2A and pepMKK3b. For clarity, the overlaid p38α proteins are not shown here.

Phosphorylation Sites.

p38α activity is modulated by phosphorylation. Like other MAPKs, p38α activation requires dual phosphorylation of a Thr–X–Tyr motif located on the activation segment, also known as the phosphorylation lip (Thr-180–X–Tyr-182). In the present structure, this motif is found at the interface with MK2, where it participates in the formation of an intermolecular antiparallel β-sheet with MK2 and in direct intermolecular interactions between Tyr-182 and a previously unrecognized MK2 pocket (Fig. 3B). Because of steric limitations in this pocket, we predict that phosphorylation of Tyr-182 weakens the αH′-mediated interface with MK2. However, weakening of the αH′-mediated interface would not necessarily lead to dissociation of the whole complex, because the MK2:activated-p38α complex still maintains a strong binding affinity (Kd 6.3 nM) (26). Such residual binding likely results from the docking interactions involving the MK2 C terminus. So, phosphorylation of the p38α Thr–X–Tyr motif not only participates in the catalytically active enzyme conformation but is now proposed to disfavor reassociation of the p38α phospho-Tyr-182 to its MK2-binding pocket.

Active p38α phosphorylates MK2 mainly at Thr-222′, Ser-272′, and Thr-334′ (43), which attenuates the affinity of the binary complex MK2:p38α by an order of magnitude (26). Thr-222′ is located on the activation loop and does not form a direct interaction with p38α. Ser-272′ is located in a disordered region of the protein in the present complex. Thr-334′ is located in a loop preceding α-helix αH′ and is buried. Phosphorylation at Thr-334′ leads to a large conformational change of an autoinhibitory domain in MK2 (30, 44). Such a conformational change unmasks not only the MK2 substrate-binding site (20) but also its NES that ultimately leads to cytoplasmic translocation of the binary complex (17). On the basis of the MK2:p38α topological arrangement, it is now proposed that the phospho-Thr-334′-induced large conformational change will also affect the interface between the two proteins in the binary complex.

Noncatalytic Role of Phosphorylation.

It has been proposed that MK2 translocation to the cytoplasm is associated with the unmasking of its NES 356′-M-X3-L-X2-M-X-V-365′ (16). In the present structure, MK2 NES is shielded from solvent (Fig. 1B) and thus inaccessible for efficient recognition by the cellular transport system. Evidence suggests that MK2 NES unmasking depends on phosphorylation of the p38α Thr-180–X–Tyr-182 phosphorylation lip motif and on MK2 Thr-334′ (16, 17, 21, 44). To achieve this unmasking in the MK2:p38α complex, there is either a domain motion between the MK2 docking region and residues 1′–334′, successive binding/dissociation events of these two proteins, or intermolecular (trans) phosphorylation. The reduced binding affinity of the activated MK2:activated p38α assembly (26) and the previously reported fluorescence resonance energy transfer analyses (21) suggest that the domain motion hypothesis is reasonable.

Methods

p38α Protein.

The murine p38α gene was PCR-cloned in pET3a expression vector (Novagen, San Diego, CA). The His-5 tag protein was expressed in BL21 (DE3) (Novagen) Escherichia coli cells. The ensuing bacterial cell pellet containing p38α was resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, and 4 μg/ml leupeptin/pepstatin A) and lysed by sonication. p38α was purified with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), eluted with imidazole, and dialyzed against buffer B (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 25 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT). p38α was further purified with a MacroprepQ column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) preequilibrated with buffer A without NaCl, eluted with a linear gradient from 25 mM to 1.0 M NaCl, and concentrated to 15 mg/ml.

MK2 Protein.

The human mapkapk2 gene encoding residues 47–400 was PCR amplified in a form compatible with the Gateway cloning (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Deletion of N-terminal residues 1–47 has previously been shown to have little effect on MK2 basal activity (30). The amplified gene was cloned into a pET16b (Novagen) vector modified to contain the recombination sites that use the Gateway recombination system. MK2 was expressed in BL21 (DE3) (Novagen) E. coli cells at 25°C with carbenicillin and chloramphenicol selections. A cell pellet containing the expressed MK2 fusion protein was resuspended in lysis buffer C [20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), 0.02% Tween 20, 1 mM phenyl-methylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 8 μg/ml pepstatin A, 8 μg/ml of leupeptin, DNase I and II, and RNase I) and lysed by sonication. The protein was purified with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), preequilibrated with buffer D (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 3 mM BME, and 0.1% Tween 20), eluted with imidazole, and dialyzed against buffer E (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 3 mM DTT). The tag was cleaved off with thrombin. MK2 was further purified with a MonoS column (Bio-Rad) preequilibrated with buffer F (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 3 mM DTT, and 0.02% Tween), eluted with a linear gradient from 0.1 to 1.0 M NaCl, and concentrated to 15 mg/ml.

MK2:p38α Complex Crystallization.

Equal molar aliquots of each protein were quickly mixed and purified with a 16/60 S-200 column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) that was preequilibrated in buffer G (20 mM Tris, pH 7.7, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 2 mM DTT). The eluted MK2:p38α complex was concentrated to 14–16 mg/ml. MK2:p38α crystals were obtained by vapor diffusion using hanging drops at room temperature, with drops of an equal amounts of protein and reservoir solutions. The reservoir solution contained 5–20% PEG 4K, 100 mM sodium citrate, pH 5.5–6.5, and 5 mM DTT. Rod-shaped crystals typically appeared in 7–21 days and continued to grow to a typical size of 40 μm × 40 μm × 250 μm within 4 weeks. The crystals were treated with 20% glycerol before being flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

X-Ray Diffraction Data Collection, Phasing, and Refinement.

X-ray diffraction data were measured at 100 K at the ID-31 beamline (SGX-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source by using a wavelength of 0.9793 Å. The diffraction data were indexed, integrated, and reduced to intensities by using D*TREK (45). The crystal structure of MK2:p38α was determined by molecular replacement method using AMoRe (46) as implemented in CCP4 (47). MK2 catalytic domain (35) and p38α protein (36) were used as search models. The asymmetric unit contained one protein molecule of each MK2 and p38α and 60 ordered water molecules. The model was refined with CNX (Accelrys, San Diego, CA) and REFMAC5 (48) by using standard stereochemical parameters (49) as ideal geometry. The refinement was interspaced with model rebuilding by using O (50). There were three (φ,ψ) angle pairs that were either in the generously allowed or disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Goldberg, Neil Moss, and Xiang Li for critical reading of the manuscript; Gerry Bell, Natalie Fuschetto, and Elda Gautschi for assistance with the protein production; and Stephen Wasserman and SGX Pharmaceuticals, Inc., (San Diego, CA) for data acquisition. Use of the Advanced Photon Source is supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the SGX-CAT beamline at sector 31 of the Advanced Photon Source was provided by SGX Pharmaceuticals, Inc., who constructed and operate the facility.

Abbreviations

- a-MK2

partially active MK2

- CD

common docking domain

- C-lobe

C-terminal lobe

- ED

glutamate–aspartate site

- i-MK2

inactive MK2

- MEF2A

myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2A

- MK2

MAPK-activated protein kinase-2

- MKK3b

MAPK kinase 3b

- NES

nuclear export signal

- N-lobe

N-terminal lobe

- NLS

nuclear localization signal.

Note Added in Proof.

Since the submission of this manuscript, the structure of a similar complex solved at the significantly lower resolution of 4Å has been reported online (51).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and observed amplitudes have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2OZA).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701679104/DC1.

References

- 1.Lee JC, Badger AM, Griswold DE, Dunnington D, Truneh A, Votta B, White JR, Young PR, Bender PE. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;696:149–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb17149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pargellis C, Tong L, Churchill L, Cirillo PF, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Grob PM, Hickey ER, Moss N, Pav S, et al. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:268–272. doi: 10.1038/nsb770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pargellis C, Regan JR. Curr Opin Invest Drugs. 2003;4:566–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinarello CA. Curr Opin Immunol. 1991;3:941–948. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(05)80018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Ann Rev Immunol. 1996;14:397–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beardmore VA, Hinton HJ, Eftychi C, Apostolaki M, Armaka M, Darragh J, McIlrath J, Carr JM, Armit LJ, Clacher C, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10454–10464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10454-10464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen M, Svensson L, Roach M, Hambor J, McNeish J, Gabel CA. J Exp Med. 2000;191:859–870. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisondi P, Gubinelli E, Cocuroccia B, Girolomoni G. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004;3:175–183. doi: 10.2174/1568010043343903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chew AL, Bennett A, Smith CH, Barker J, Kirkham B. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:492–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlieb AB, Evans R, Li S, Dooley LT, Guzzo CA, Baker D, Bala M, Marano CW, Menter A. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuki KG, Bresnihan B, Bear MB, McCabe D. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2838–2846. doi: 10.1002/art.10578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winzen R, Kracht M, Ritter B, Wilhelm A, Chen CY, Shyu AB, Muller M, Gaestel M, Resch K, Holtmann H. EMBO J. 1999;18:4969–4980. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotlyarov A, Neininger A, Schubert C, Eckert R, Birchmeier C, Volk HD, Gaestel M. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:94–97. doi: 10.1038/10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegen M, Gaestel M, Nickerson-Nutter CL, Lin LL, Telliez JB. J Immunol. 2006;177:1913–1917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansen C, Funding AT, Otkjaer K, Kragballe K, Jensen UB, Madsen M, Binderup L, Skak-Nielsen T, Fjording MS, Iversen L. J Immunol. 2006;176:1431–1438. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotlyarov A, Yannoni Y, Fritz S, Laass K, Telliez JB, Pitman D, Lin LL, Gaestel M. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4827–4835. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4827-4835.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Levy R, Hooper S, Wilson R, Paterson HF, Marshall CJ. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engel K, Kotlyarov A, Gaestel M. EMBO J. 1998;17:3363–3371. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belka C, Ahlers A, Sott C, Gaestel M, Herrmann F, Brach MA. Leukemia. 1995;9:288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng W, Swenson LL, Fitzgibbon MJ, Hayakawa K, Ter Haar E, Behrens AE, Fulghum JR, Lippke JA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37401–37405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neininger A, Thielemann H, Gaestel M. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:703–708. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pomérance M, Quillard J, Chantoux F, Young J, Blondeau JP. J Pathol. 2006;209:298–306. doi: 10.1002/path.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Y, Gaestel M. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1519–1536. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoecklin G, Stubbs T, Kedersha N, Wax S, Rigby WF, Blackwell TK, Anderson P. EMBO J. 2004;23:1313–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hitti E, Iakovleva T, Brook M, Deppenmeier S, Gruber AD, Radzioch D, Clark AR, Blackshear PJ, Kotlyarov A, Gaestel M. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2399–2407. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2399-2407.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukas SM, Kroe RR, Wildeson J, Peet GW, Frego L, Davidson W, Ingraham RH, Pargellis CA, Labadia ME, Werneburg BG. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9950–9960. doi: 10.1021/bi049508v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang WX, Wang R, Wisniewski D, Marcy AI, LoGrasso P, Lisnock JM, Cummings RT, Thompson JE. Anal Biochem. 2005;343:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith JA, Poteet-Smith CE, Lannigan DA, Freed TA, Zoltoski AJ, Sturgill TW. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31588–31593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zu YL, Wu F, Gilchrist A, Ai Y, Labadia ME, Huang CK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200:1118–1124. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zu YL, Ai Y, Huang CK. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:202–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanoue T, Maeda R, Adachi M, Nishida E. EMBO J. 2001;20:466–479. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanoue T, Adachi M, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:110–116. doi: 10.1038/35000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang CI, Xu BE, Akella R, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1241–1249. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:2177–2198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Underwood KW, Parris KD, Czerwinski RM, Shane T, Taylor M, Svenson K, Liu Y, Hsiao CL, Wolfrom S, Maguire M, et al. Structure (London) 2003;11:627–636. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, Harkins PC, Ulevitch RJ, Han J, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2327–2332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tong L, Pav S, White DM, Rogers S, Crane KM, Cywin CL, Brown ML, Pargellis CA. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanoue T, Nishida E. Cell Signal. 2003;15:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stokoe D, Caudwell FB, Cohen PTW, Cohen P. Biochem J. 1993;296:843–849. doi: 10.1042/bj2960843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaestel M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:120–130. doi: 10.1038/nrm1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou T, Sun L, Humphreys J, Goldsmith EJ. Structure (London) 2006;14:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heo YS, Kim SK, Seo CI, Kim YK, Sung BJ, Lee HS, Lee JI, Park SY, Kim JH, Hwang KY, et al. EMBO J. 2004;23:2185–2195. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ben-Levy R, Leighton IA, Doza YN, Attwood P, Morrice N, Marshall CJ, Cohen P. EMBO J. 1995;14:5920–5930. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engel K, Schultz H, Martin F, Kotlyarov A, Plath K, Hahn M, Heinemann U, Gaestel M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27213–27221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pflugrath JW. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:1718–1725. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Navaza J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engh RA, Huber R. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ter Haar E, Prabakhar P, Liu X, Lepre C. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611165200. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.