Abstract

Progression of human prostate cancer toward therapy resistance occurs in the presence of wild-type or mutated androgen receptors (ARs) that, in some cases, exhibit aberrant activation by various steroid hormones and anti-androgens. The AR associates with a number of co-activators that possess histone acetylase activity and act as bridging molecules to components of the transcription initiation complex. In previous reports, it was shown that the transcriptional co-activator CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein)-binding protein (CBP) enhances AR activity in a ligand-dependent manner. In the present study, we have investigated whether CBP modifies antagonist/agonist balance of the nonsteroidal anti-androgens hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide. In prostate cancer DU-145 cells, which were transiently transfected with CBP cDNA, hydroxyflutamide enhanced AR activity to a greater extent than bicalutamide in the presence of either wild-type or the mutated AR 730 val→met. In two sublines of LNCaP cells that contain the mutated AR 877 thr→ala and overexpressed CBP, increase in AR activity was observed after treatment with hydroxyflutamide but not with bicalutamide. Anti-androgens did not influence AR expression in cells transfected with CBP cDNA, as judged by Western blot analysis. Endogenous CBP protein was detected by Western blot in nuclear extracts from the three prostate cancer cell lines, LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145, all derived from therapy-resistant prostate cancer. In addition, CBP was expressed in both basal and secretory cells of benign prostate epithelium, high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia, and prostate cancer clinical specimens, as evidenced by immunohistochemical staining. Taken together, our findings demonstrate the selective enhancement of agonistic action of the anti-androgen hydroxyflutamide by the transcriptional co-activator CBP, which is a new, potentially relevant mechanism contributing to the acquisition of therapy resistance in prostate cancer.

Endocrine therapy for prostate cancer, which is the most commonly diagnosed male malignant tumor in industrialized countries, is based on the classic work of Huggins and Hodges. 1 They were the first who reported on the dependence of prostate cancers on androgenic stimulation. 1 Treatment modalities include surgical castration (orchiectomy) or application of gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. Although it was suggested that the additional use of androgen receptor (AR) antagonists results in a more efficient suppression of androgenic stimulation of prostate cancer cell growth, 2 recent studies have not convincingly shown that the total androgen blockade is superior to androgen withdrawal by orchiectomy or GnRH administration only. 3 However, the AR blockers hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide, which interfere with acquisition of the transcriptionally active conformation of the receptor, have to be used in the prevention of the disease flare that occurs during the initial phase of administration of GnRH. The nonsteroidal anti-androgens hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide have been tested as a monotherapy in clinical trials. 4

Failure of hormonal therapy in prostate cancer is associated with alterations in the expression and function of hormone and growth factor receptors as well as growth factors and cytokines themselves. AR protein is expressed in nearly all prostate cancer tissues from patients who failed endocrine therapy and is in some cases mutated or up-regulated because of amplification of the AR gene. 5,6 It was shown that increased expression of the AR may occur because of the up-regulation of mRNA or increased stability of the protein. 7,8

Several mutant ARs detected in prostate cancer were functionally characterized and those studies revealed that hydroxyflutamide rather than bicalutamide acts as an agonist in the presence of structurally altered ARs. 9 In one study, AR mutations were found in 5 of 16 prostate cancer specimens from patients who received flutamide. 10 Those patients responded to the second-line treatment with bicalutamide. We have reasoned that differences in the regulation of AR activity by the two nonsteroidal anti-androgens should be further explored. One possibility that should be tested is that alterations in the expression and function of AR-associated co-regulatory proteins occur.

Functional activity of the AR is enhanced by co-activators, which have histone acetylase activity and act as bridging factors between steroid receptors and components of the transcription initiation complex. Although it was demonstrated that a number of proteins interact with the AR and enhance its functional activity, significance of these interactions for prostate cancer remains primarily unknown. AR activity was stimulated by both nonsteroidal and steroidal anti-androgens in the presence of the AR-associated protein ARA70. 11 The up-regulation of the co-activators SRC-1, TIF-2, and RAC3 in advanced prostate cancer suggests that these proteins play a role in the development of resistance to endocrine therapy. 12,13 One of the proteins that augments AR activity in a ligand-dependent manner is CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein)-binding protein (CBP). 14,15 Moreover, Fu and associates 16 demonstrated that the AR is acetylated by the CBP-related protein p300 and that a p300 mutation results in a reduced ligand-dependent activation of the AR. The CBP-associated factor P/CAF rescued cyclin D1-mediated trans-repression of the AR. 17 CBP is implicated in the cross-talk between the AR and the activator protein-1 pathway, which consists of Jun and Fos oncoproteins and can block AR activity. 14 CBP acts not only as a steroid receptor co-activator but it has a key role in the control of activity of various genes involved in the regulation of proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, such as the cell-cycle inhibitor p21WAF1. 18,19 CBP and p300 have a tumor suppressor-like activity, which is altered in a variety of human cancers. CBP mutations that result in the generation of truncated proteins were detected in malignant neoplasms. 20 p300/CBP proteins might nucleate the assembly of various co-factor proteins into a large co-activator complex, 21 which explains their involvement in the regulation of multiple signaling pathways. Association of p300/CBP with p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) could be of importance for the modulation of AR activity. 22 The MAPK pathway is implicated in ligand-independent activation of the AR. 23,24 In the present study, we have addressed the question whether CBP is involved in the acquisition of agonistic properties of nonsteroidal anti-androgens and investigated its expression in prostate cancer cell lines and patient specimens by Western blot and immunohistochemistry.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). LNCaP-abl cells were generated after long-term androgen ablation in vitro and previously characterized. 25 PC-3 and DU-145 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (HyClone, Logan, UT) and LNCaP and LNCaP-abl cells in MCDB 131 medium (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands). Media were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin (PAA Laboratories, Linz, Austria). MCDB 131 medium was supplemented with sodium pyruvate, glucose, and HEPES buffer, pH 7.2. LNCaP-abl growth medium contained charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum.

Chemicals

The synthetic androgen methyltrienolone (R1881) and 3H-labeled acetyl-CoA were purchased from New England Nuclear (Dreieichenhain, Germany). Chloramphenicol and unlabeled acetyl-CoA were from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). Hydroxyflutamide was kindly provided by Essex Pharma (Munich, Germany) and bicalutamide was synthesized at Schering AG (Berlin, Germany). Dual luciferase reporter assay was from Promega (Madison, WI). The polyclonal anti-CBP antibody A-22 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and the monoclonal anti-AR antibody F 39.4.1 from BioGenex (San Ramon, CA). An anti-mouse secondary antibody was a product of Amersham (Amersham Place, UK). Nuclear and cytoplasmatic extraction reagents were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL) and The PicTure kit for immunohistochemical detection from Zymed Laboratories (San Francisco, CA).

Co-Transfection-Transactivation Assays

DU-145 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at a cell density of 45,000 cells/well. Liposome-mediated transfection was performed with 0.4 μg/well of the androgen-inducible reporter plasmid ARE2TATA-CAT, 0.08 μg/well of either wild-type or mutated AR 730 val→met cDNA, and 0.015 μg/well of the CBP expression vector pCMV CBP (kindly provided by Dr. R. Eckner, Institute for Molecular Biology, University of Zurich, Switzerland). A portion of cells was transfected with the same reporter and AR cDNA as described above but instead of CBP cDNA the empty vector driven by the same CMV promoter (5 × 10−3 μg/well, plasmid was gift from Dr. F. Saatcioglu, Biotechnology Centre, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway) was included. For transfection, lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) was used. The synthetic androgen methyltrienolone and/or AR antagonists were added 24 hours after transfection and the cells were incubated for 24 hours. Reporter gene activity was measured by CAT assay. LNCaP and LNCaP-abl cells were grown on six-well plates and 300,000 cells/well were transfected with 0.7 μg of the androgen-inducible reporter pGL3E-probasin along with 0.05 μg of CBP cDNA. For transfection of LNCaP cells, the probasin construct was used because liposome-mediated transfection with the ARE2TATA-CAT reporter resulted in a very low reporter gene activity. To measure the efficiency of the transfection, the renilla luciferase plasmid pRLTK was co-transfected. The dual luciferase assay for measurement of reporter gene activity after incubation with androgen and/or AR blockers was used. Because of different transfection efficacies in individual experiments, relative values from the co-transfection-transactivation assays have been calculated.

AR Western Blot Analysis

For AR Western blot, DU-145 cells were seeded onto 12-well plates (85,000 cells/well) and transfected as described for the transactivation experiments. After treatment with either androgen or anti-androgen, the cells were collected in NuPAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen), sonicated, and boiled for 10 minutes at 70°C. The lysates were loaded on a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel and run with 1× NuPAGE sodium dodecyl sulfate running buffer for 1 hour. After sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to the Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) with the Xcell blot module for 1 hour at 30 V using NuPAGE transfer buffer. After the transfer procedure, the membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) once for 5 minutes and in TBS with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) three times for 5 minutes. The membranes were preincubated with 5% skim milk in TBST (TBSTM) for 1 hour and then incubated with the anti-AR antibody (dilution, 1:1000) overnight at 4°C. After two washes in TBS and five in TBST, the membranes were incubated with the anti-mouse secondary antibody. Then they were washed twice with TBS, five times with TBST, and the final wash step was with TBS. Western blots were developed by means of the ECL Plus substrate (Amersham). As a control for equal protein loading, Western blot for β-actin was performed.

Assessment of CBP Expression in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

To detect CBP expression in prostate cancer cells, Western blot analysis was performed in the cell lines LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145. Nuclear extracts were prepared from 2 × 106 cells using nuclear and cytoplasmatic extraction reagents. The anti-CBP antibody was applied at a dilution 1:100 in Western blot. The Western blot procedure was basically the same as that described above.

Tissue Specimens

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues from 49 patients with prostatic adenocarcinoma were selected for this study. The tumor cases were separated into three groups. In the first group, there were tissue samples from 23 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy. They did not receive endocrine treatment before surgery. In the second group, there were eight patients who received neoadjuvant treatment for 3 to 4 months with AR blockers before radical prostatectomy. From those patients, five prostate tissue samples and three lymph nodes were obtained. The third group consisted of 23 lymph node metastases from 18 patients who underwent diagnostic pelvic lymphadenectomy. Those patients did not receive any endocrine therapy. The slides were reviewed and Gleason pattern was determined on prostate tumor tissue. 26 For each case, one representative tissue block was used for immunohistochemistry. The expression of CBP was analyzed in nine samples in tumor-adjacent benign tissue and in four cases in high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia.

Immunohistochemistry

Five-μm-thick sections were cut and subsequently rehydrated through a series of graded alcohols followed by blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity. Pretreatment by wet autoclaving was used for antigen retrieval. 27 The sections were incubated overnight with the polyclonal antibody against CBP. The dilution of the primary antibody was 1:100 in TBS/1% human serum. The PicTure kit based on a one step immunohistochemical detection method with the horseradish peroxidase/Fab polymer conjugate and development with diaminobenzidine was used for visualization. All cases had a negative control that was run simultaneously with the test slide in which the primary antibody was omitted. The cytokeratin AE1/AE3 served as a fixation control and was diffusely strong reactive in all adenocarcinoma samples.

Evaluation of staining in benign (secretory and basal cells), premalignant, and malignant prostatic epithelium was performed on the basis of a five-point scale (0, <5% of cells positive; 1, 5 to 20% of cells positive; 2, 20 to 50% of cells positive; 3, >50% of cells positive, low intensity (appearance on high-power magnification); 4, >50% of cells positive, high intensity (appearance on low-power magnification).

Results

Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Androgens on AR Activity in DU-145 and LNCaP Cells in the Presence of Overexpressed CBP

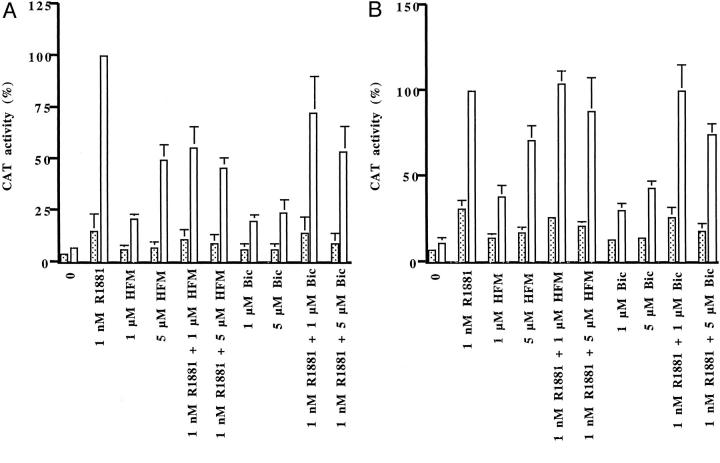

Consistent with previous reports, the synthetic androgen R1881 enhanced AR activity in DU-145 cells that overexpressed wild-type AR and CBP cDNA by fivefold in comparison with androgen-treated cells that expressed the empty plasmid (Figure 1A) ▶ . 14,15 There were differences in the magnitude of AR activity induced by hydroxyflutamide or bicalutamide in the presence of the overexpressed co-activator. Hydroxyflutamide, at a concentration of 5 μmol/L, induced 50% of the maximal CAT activity caused by the synthetic androgen R1881, whereas bicalutamide-induced reporter gene activity was 24%. When either anti-androgen was added in combination with R1881, somewhat higher reporter gene activities were observed in cells treated with androgen and bicalutamide. Lower antagonistic activity of bicalutamide than that of hydroxyflutamide was reported previously under different experimental conditions. 28,29

Figure 1.

AR activity in the absence (dotted bars) or presence (open bars) of overexpressed CBP in DU-145 cells transfected with the reporter gene ARE2TATA-CAT, either wild-type (A) or mutant AR 730 val→met (B), and CBP cDNA. The cells were treated with R1881 and/or hydroxyflutamide (HFM) or bicalutamide (Bic) and CAT activity was measured. Reporter gene activity measured after treatment of CBP-transfected cells with 1 nmol/L of R1881 was set as 100% and all other activities are expressed in relation to that value.

The studies in DU-145 cells were continued with the mutated AR 730 val→met, which was discovered in a specimen of clinically localized prostate cancer. 30 Functional characterization of that mutated AR revealed increased activation by metabolic products of dihydrotestosterone and hydroxyflutamide. 31 The aim of those experiments was to assess a contribution of CBP to the enhanced activation. CAT activities induced by hydroxyflutamide in the presence of transfected CBP were higher with the mutated than with the wild-type AR (Figure 1B) ▶ . Although CBP also potentiated AR functional activity induced by bicalutamide, the levels achieved were lower than those obtained by hydroxyflutamide, at a concentration of 5 μmol/L. CBP also contributed to the reduction of antagonistic properties of hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide with the mutated AR, as evidenced by measurement of reporter gene activity after treatment with R1881 and anti-androgen.

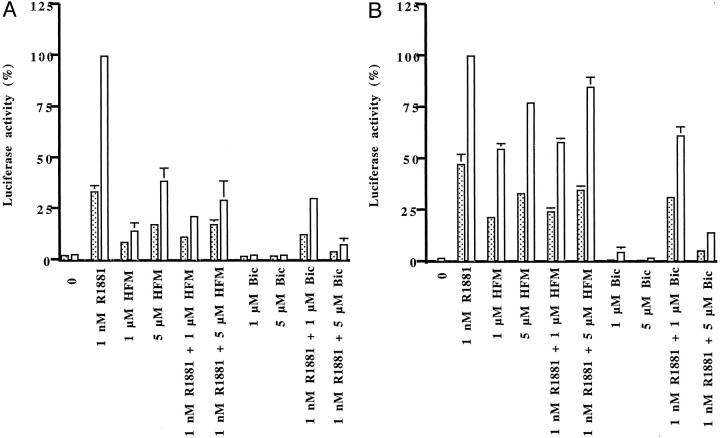

Then we have investigated how overexpression of CBP influences antagonist/agonist balance of nonsteroidal anti-androgens in LNCaP cells that express endogenous AR. In that cell line, the differences in activation of the AR between hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide were more pronounced than in DU-145 cells. In experiments in which AR blockers were applied alone, luciferase activity was induced in the presence of CBP with hydroxyflutamide (1 and 5 μmol/L) but not with bicalutamide (Figure 2A) ▶ . Androgen-induced reporter gene activity was down-regulated to a greater extent by 5 μmol/L of bicalutamide than by an equimolar concentration of hydroxyflutamide both in CBP-transfected and -nontransfected cells. These results could be explained with the mutation of the AR in LNCaP cells, which renders the receptor more sensitive to stimulation by hydroxyflutamide. In addition, we have explored the action of anti-androgens in LNCaP-abl cells derived after long-term steroid ablation in vitro. 25 In long-term steroid-deprived cells, AR activities induced by hydroxyflutamide were higher both in the absence or presence of overexpressed CBP than those assessed in parental LNCaP cells (Figure 2B) ▶ . Interestingly, bicalutamide did not exhibit agonistic activities with the probasin reporter in androgen-ablated cells regardless whether they expressed CBP cDNA or not. Collectively, our findings indicate that in the presence of CBP, hydroxyflutamide induces higher reporter gene activity than bicalutamide with the wild-type and the mutated AR 730 val→met and AR 877 thr→ala. The presence of CBP differentially influenced action of bicalutamide with the two mutant receptors; antagonism was abolished with the AR 730 val→met but not with the LNCaP AR 877 thr→ala.

Figure 2.

Enhancement of AR activity by CBP in LNCaP (A) and long-term steroid-deprived LNCaP-abl (B) cells. LNCaP cells were transfected with the reporter plasmid pGL3E-probasin and CBP cDNA and treated with R1881 and/or anti-androgens for 24 hours. Luciferase activities are expressed in relation to values measured in CBP-overexpressing cells treated with R1881; dotted bars, cells transfected with empty plasmid; open bars, cells transfected with CBP cDNA.

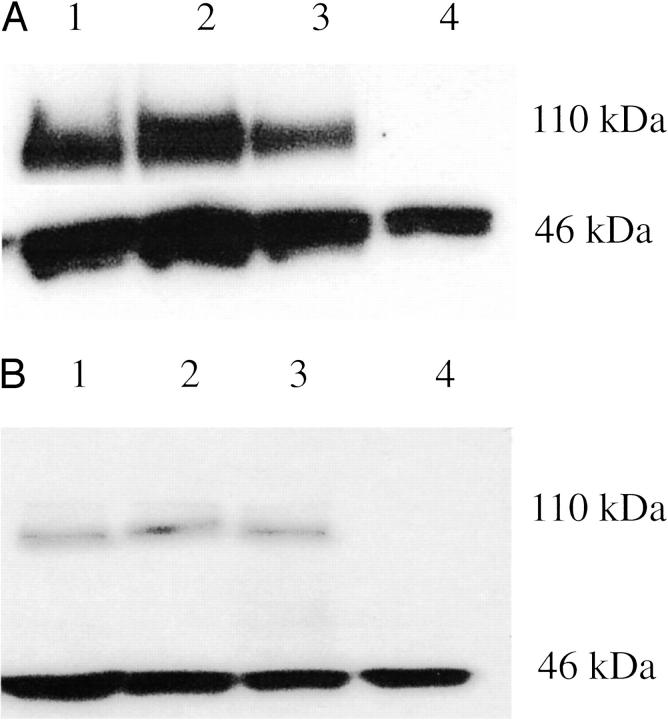

Anti-Androgens Do Not Alter AR Expression in the Presence of CBP

Next we examined whether the effects of anti-androgens on AR activity in cells that contain CBP occur because of the up-regulation of AR expression. For this purpose, DU-145 cells were transfected with AR and CBP plasmids and AR expression was assessed by Western blot analysis after treatment with R1881 or anti-androgens. As shown in Figure 3, A and B ▶ , neither R1881 nor AR blockers caused appreciable changes in AR expression when CBP was overexpressed.

Figure 3.

Regulation of AR protein expression in DU-145 cells overexpressing CBP. DU-145 cells were transfected as described in the legend for Figure 1 ▶ and the cells were treated with androgen, hydroxyflutamide, or bicalutamide. After sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, Western blots for the AR (top) and β-actin (internal control, bottom) were performed; lane 1, transfected DU-145 cells, treatment with either hydroxyflutamide (A) or bicalutamide (B); lane 2, transfected cells, treatment with R1881; lane 3, untreated transfected cells; lane 4, nontransfected cells.

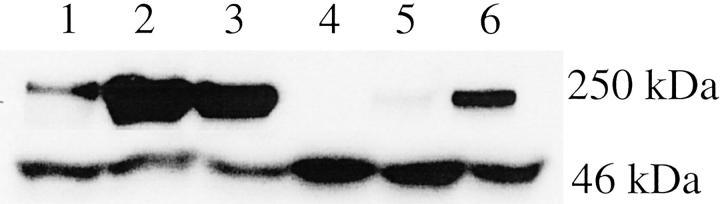

CBP Is Expressed in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

To assess the relevance of our findings with cells transfected with CBP cDNA to human carcinoma of the prostate, we have investigated endogenous CBP expression in the three prostate cancer cell lines, LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145. All of the cell lines were derived from metastatic lesions from prostate cancer patients. 32-34 CBP was detected by immunoblotting in nuclei of all cell lines (Figure 4) ▶ and the expression in nuclear extracts was higher in either LNCaP or PC-3 than in DU-145 cells. Interestingly, there was also expression of CBP in cytoplasmatic preparations of LNCaP and PC-3 cells.

Figure 4.

Expression of CBP in prostate cancer cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from the cell lines LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145 using nuclear and cytoplasmatic extraction reagents. Western blots for CBP (top) and β-actin (bottom) in nuclear (lanes 1 to 3) and cytoplasmatic (lanes 4 to 6) preparations were performed; lanes 1 and 4, DU-145 cells; lanes 2 and 5, PC-3 cells; lanes 3 and 6, LNCaP cells.

Immunohistochemical Localization of CBP in Benign, Premalignant, and Malignant Prostate Tissue

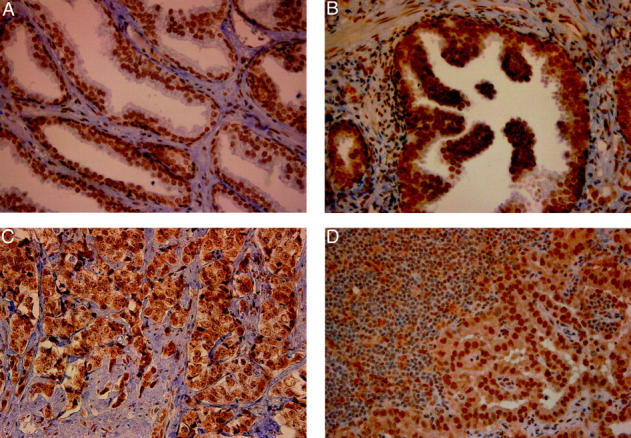

The studies on the expression of CBP in prostate cancer cells were extended on tissue specimens from patients who underwent radical prostatectomy, received neoadjuvant endocrine therapy before prostate surgery, or underwent diagnostic pelvic lymphadenectomy, respectively. Staining was evaluated on the basis of a semiquantitative scale, which considered both percentage of positive cells and staining intensity (Table 1) ▶ . Although immunohistochemical reaction was confined mainly to the cell nuclei, there was also some positive staining in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5) ▶ . In benign prostate epithelium, both basal and secretory cells were CBP-positive in all nine cases investigated (Fig. 5a) ▶ . CBP was also detectable in four high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia lesions (Fig. 5b) ▶ . In malignant prostatic tissue, the expression of CBP was investigated in the Gleason patterns 2 to 5 (n = 38) (Table 1) ▶ . CBP expression was lost in only three primary tumors and in 2 of 26 lymph node metastases.

Table 1.

Expression of the Transcriptional Co-Activator CBP in Benign, Premalignant, and Malignant Prostate Tissues

| Tissue | n | Immunohistochemical staining | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Benign | ||||||

| Basal cells | 9 | – | – | – | 6 | 3 |

| Secretory cells | 9 | – | 2 | 5 | 2 | – |

| PIN | 4 | – | 1 | – | 3 | – |

| Cancer | ||||||

| Gleason pattern | ||||||

| 2 | 2 | – | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| 3 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| 4 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 |

| 5 | 9 | – | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| LNM | 26 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 6 |

Immunohistochemical staining: 0, up to 5% of the cells stained positive; 1, 5 to 20% positive cells; 2, 20 to 50% positive cells; 3, >50% positive cells, low staining intensity; 4, >50% positive cells, high staining intensity.

PIN, high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia; LNM, lymph node metastasis.

Figure 5.

Expression of CBP in benign (A), high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (B), and malignant [primary prostate cancer, Gleason pattern 5 (C); and lymph node metastasis (D)] prostate tissue. The sections were incubated with the polyclonal anti-CBP antibody, dilution 1:100. For visualization, the PicTure kit was used. In benign prostate tissue, basal and secretory cells are CBP-positive. Original magnifications, ×400.

Discussion

Acquisition of agonistic properties of AR antagonists in prostate cancer is of interest because of a widespread use of these drugs in endocrine therapy. In several studies on AR expression and structure in carcinoma of the prostate, it was reported that hydroxyflutamide acts as an agonist with mutated receptors. 31,35,36 Partial agonism of hydroxyflutamide was also demonstrated with the wild-type AR in reporter gene assays and DNA-binding experiments. 31,37 The two prostate cancer cell lines, LNCaP and MDA PCa 2a, obtained from patients with metastatic disease contain mutated ARs that are activated by hydroxyflutamide but not by bicalutamide. 38,39 There is a consensus that frequency of AR point mutations in prostate cancer increases with progression toward resistance to therapy. 40,41 For these reasons, it is important to study the mechanisms by which hydroxyflutamide acquires agonistic properties in human prostate cancer. It was shown that agonist and antagonist properties of hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide correlate with the ability of these drugs to stabilize the AR. 28 Thus, in LNCaP cells the AR was completely stabilized by 1 μmol/L of hydroxyflutamide whereas bicalutamide, at a concentration of 10 μmol/L, caused only a slight receptor stabilization. In our study, we confirm that both hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide have mixed antagonistic/agonistic properties. There was a stronger inhibition of the wild-type AR activity by hydroxyflutamide in previous studies in CV-1 cells that do not originate from the prostate and were not used in the present study. 37

In this study, we show that antagonist/agonist balance of nonsteroidal anti-androgens is influenced by the transcriptional co-activator CBP. Enhancement of agonistic activities of AR antagonists was also reported for the AR-associated protein ARA70. 11 The major difference between the actions of ARA70 and CBP in the presence of anti-androgens is that the stimulation of agonistic properties by ARA70 is not selective. The levels of reporter gene activity measured in cells transfected with ARA70 cDNA and treated with either anti-androgenic compound hydroxyflutamide, bicalutamide, cyproterone acetate, or RU 58841 were similar. 11 In this context, it is important to note that the increase in AR activity by ARA70 or CBP is achieved by two different mechanisms: whereas androgens and anti-androgens promote physical interaction between the AR and ARA70, the association between the AR and CBP is not influenced by the ligand. 11,14,15 Our findings showing that AR expression is not altered by anti-androgens in DU-145 cells are consistent with previous data that the levels of immunoreactive ARs are not changed by androgen in cells transfected with AR and CBP cDNA. 15 In LNCaP cells, however, androgenic hormones enhance AR expression by protein stabilization even when neither co-activator is overexpressed. 42,43 This would compromise interpretation of results of any immunoblot experiments similar to those performed in DU-145 cells.

The up-regulation of the AR co-activators SRC-1 and TIF-2 was documented in a collective of patients with recurrent carcinoma of the prostate. 8 Gregory and associates 8 reported that those co-activators potentiate AR activation by adrenal androgens, which were shown to increasingly stimulate function of mutated AR. 5,8,36 Expression of the co-activator RAC3, which belongs to the same p160 family of co-activators as SRC-1, correlated with prostate tumor grade and stage. 13 Taken together, those findings indicate that prostate cancer progression is associated with overexpression of some AR co-activators. Because of ethical concerns, it was not possible for us to analyze CBP expression in clinical specimens from patients with therapy-resistant carcinoma of the prostate. However, all cell lines used were obtained from patients who had advanced prostate cancer and they express the CBP protein. In future studies, it will be necessary to address the issue of regulation of CBP expression by steroids and peptide hormones in prostate cancer cells. That information, in connection with data on CBP expression in clinical specimens from patients with therapy-resistant disease, could improve understanding of the role of CBP in prostate cancer progression. The ability of CBP to stimulate agonistic action of hydroxyflutamide to a higher level than that of bicalutamide was not limited to the wild-type AR and was also seen with two mutated AR and in the subline of LNCaP cells, which was established after long-term androgen ablation. In our previous study, we noted that bicalutamide caused a twofold stimulation of AR activity in LNCaP-abl cells. 25 However, in that study a different reporter gene and transfection method were used, which could at least partly explain the different results obtained after bicalutamide treatment. Reduced antagonism of bicalutamide was observed in the presence of the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase and β-catenin. 44,45 Bicalutamide also enhanced the proliferation of a LNCaP subline generated after long-term treatment with tumor necrosis factor-α and, possibly, that effect was associated with the stimulation of AR activity. 46 The results of the present study do not rule out an involvement of CBP in those activation processes. Alternatively, one or more other AR co-activators might account for diminished antagonism of bicalutamide with HER-2/neu or β-catenin. In clinical studies, the anti-androgen withdrawal syndrome, characterized by a temporary improvement in symptoms and prostate-specific antigen serum levels decline after cessation of anti-androgen therapy was first described for hydroxyflutamide. 47 In subsequent studies, however, similar findings with bicalutamide were reported. 48-50 Recently, mutated ARs were detected in samples from patients whose tumors relapsed after a combined androgen blockade by orchiectomy and bicalutamide. 51 It is, however, not known whether those mutants are increasingly activated by bicalutamide.

The detection of the CBP protein in all prostate cancer cell lines studied is consistent with the results of our previous study, in which CBP mRNA was detected in prostate epithelial cells by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. 52 On immunohistochemistry, CBP was present in the vast majority of prostate cancer specimens. Thus, in future experimental studies its interaction with key regulators of tumor growth should be addressed. In two of three cell lines and in clinical specimens, we found that CBP is expressed in both nucleus and cytoplasm. Functional significance of cytoplasmic expression is not clear but, in this context, it should be noted that similar observations were made for the co-activators FHL2 and RAC3. 13,53

Because of its association with a number of molecules that control proliferation and apoptosis, CBP is a good candidate to be involved in ligand-independent activation of the AR, as recently demonstrated in the case of interleukin-6. 54 Taken together, findings of our study and those reported by others indicate that the transcriptional co-activator CBP might be considered a potential therapy target in prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. F. Saatcioglu, Biotechnology Centre, University of Oslo for helpful discussions; Drs. Saatcioglu and R. Eckner, Institute for Molecular Biology, University of Zürich, for kindly providing plasmids used for this study; Dr. M. Cacic, Department of Pathology, University of Zagreb, for helpful advice; G. Sierek, H. Hübl, A. Tögel, E. Tafatsch, U. Plawenn, and G. Hölzl for expert technical assistance; and R. Schober and H. Recheis for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Zoran Culig, Department of Urology, University of Innsbruck, Anichstrasse 35, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria. E-mail: zoran.culig@uibk.ac.at.

Supported by CaP CURE and the Austrian Research Fund (grants P14709 and SFB 002 F203).

B. C. and L. L. contributed equally to this work.

A. H. and Z. C. are joint senior authors.

Present address of L. L.: Glaxo Smith Kline Greece Medical Department, L. Kifisias 266, GR 15232 Athens, Greece.

References

- 1.Huggins C, Hodges CV: Studies on prostatic cancer: the effects of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res 1941, 1:293-297 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labrie F, Dupont A, Belanger A, Lefebvre FA, Cusan L, Raynaud JP, Husson JM, Fazekas AT: New hormonal therapy in prostate cancer: combined use of a pure antiandrogen and an LHRH agonist. Horm Res 1983, 18:18-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberger MA, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, Miller G, McLeod DG, Loehrer PJ, Wilding G, Sears K, Culkin DJ, Thompson IMJ, Bueschen AJ, Lowe BA: Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 1998, 339:1036-1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackledge GR: High-dose bicalutamide monotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer. Urology 1996, 47:44-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culig Z, Hobisch A, Cronauer MV, Cato ACB, Hittmair A, Radmayr C, Eberle J, Bartsch G, Klocker H: Mutant androgen receptor detected in an advanced stage of prostatic carcinoma is activated by adrenal androgens and progesterone. Mol Endocrinol 1993, 7:1541-1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visakorpi T, Hyytinen E, Koivisto P, Tanner M, Keinänen R, Palmberg C, Palotie A, Tammela T, Isola J, Kallioniemi OP: In vivo amplification of the androgen receptor gene and progression of human prostate cancer. Nat Genet 1995, 9:401-406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokontis J, Takakura K, Hay N, Liao S: Increased androgen receptor activity and altered c-myc expression in prostate cancer cells after long-term androgen deprivation. Cancer Res 1994, 54:1566-1573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory CW, Johnson RTJ, Mohler JL, French FS, Wilson EM: Androgen receptor stabilization in recurrent prostate cancer is associated with hypersensitivity to low androgen. Cancer Res 2001, 61:2892-2898 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culig Z, Klocker H, Bartsch G, Hobisch A: Mutations of androgen receptor in carcinoma of the prostate—significance for endocrine therapy. Am J Pharmacogenomics 2001, 1:241-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taplin ME, Bubley GJ, Ko YJ, Small EJ, Upton M, Rajeshkumar B, Balk SP: Selection for androgen receptor mutations in prostate cancers treated with androgen antagonist. Cancer Res 1999, 59:2511-2515 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto H, Yeh S, Wilding G, Chang C: Promotion of agonist activity of antiandrogens by the androgen receptor coactivator, ARA70, in human prostate cancer DU145 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:7379-7384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregory CW, He B, Johnson RT, Ford OH, Mohler JL, French FS, Wilson EM: A mechanism for androgen receptor-mediated prostate cancer recurrence after androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer Res 2001, 61:4315-4319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gnanapragasam VJ, Leung HY, Pulimood AS, Neal DE, Robson CE: Expression of RAC3, a steroid hormone receptor co-activator in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 2001, 85:1928-1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fronsdal K, Engedal N, Hagsvold T, Saatcioglu F: CREB binding protein is a coactivator for the androgen receptor and mediates cross-talk with AP-1. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:31853-31859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aarnisalo P, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA: CREB binding protein in androgen receptor-mediated signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:2122-2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu M, Wang C, Reutens AT, Wang J, Angeletti RH, Siconolfi-Baez L, Ogryzko V, Avantaggiati ML, Pestell RG: p300 and p300/cAMP-response element-binding protein-associated factor acetylate the androgen receptor at sites governing hormone-dependent transactivation. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:20853-20860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reutens AT, Fu M, Wang C, Albanese C, McPhaul MJ, Sun Z, Balk SP, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ, Pestell RG: Cyclin D1 binds the androgen receptor and regulates hormone-dependent signaling in a p300/CBP-associated factor (P/CAF)-dependent manner. Mol Endocrinol 2001, 15:797-811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan HM, La Thangue NB: p300/CBP proteins: hATs for transcriptional bridges and scaffolds. J Cell Sci 2001, 114:2363-2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Missero C, Calautti E, Eckner R, Chin J, Tsai LH, Livingston DM, Dotto GP: Involvement of the cell-cycle inhibitor Cip1/WAF1 and the E1A-associated p300 protein in terminal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:5451-5455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muraoka M, Konishi M, Kikuchi R, Tanaka K, Shitara N, Chong JM, Iwama T, Miyaki M: p300 gene alterations in colorectal and gastric carcinomas. Oncogene 1996, 12:1565-1569 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG: Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opin Genet 1999, 9:140-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu YZ, Chirivia JC, Latchman DS: Nerve growth factor up-regulates the transcriptional activity of CBP through activation of the p42/p44 (MAPK) cascade. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:32400-32407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobisch A, Eder IE, Putz T, Horninger W, Bartsch G, Klocker H, Culig Z: Interleukin-6 regulates prostate-specific protein expression in prostate carcinoma cells by activation of the androgen receptor. Cancer Res 1998, 58:4640-4645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeh S, Lin HK, Kang HY, Thin TH, Lin MF, Chang C: From HER2/Neu signal cascade to androgen receptor and its coactivators: a novel pathway by induction of androgen target genes through MAP kinase in prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:5458-5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Culig Z, Hoffmann J, Erdel M, Eder I, Hobisch A, Hittmair A, Bartsch G, Utermann G, Schneider MR, Parczyk K, Klocker H: Switch from antagonist to agonist of the androgen receptor blocker bicalutamide is associated with prostate tumour progression in a new model system. Br J Cancer 1999, 81:242-251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gleason DF: Histologic grading of prostate cancer: a perspective. Hum Pathol 1992, 23:273-279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bankfalvi A, Navabi H, Bier B, Böcker W, Jasani B, Schmid KW: Wet autoclave pretreatment for antigen retrieval in diagnostic immunohistochemistry. J Pathol 1994, 174:223-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kemppainen JA, Wilson EM: Agonist and antagonist activities of hydroxyflutamide and casodex relate to androgen receptor stabilization. Urology 1996, 48:157-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avances C, Georget V, Terouanne B, Orio F, Cussenot O, Mottet N, Costa P, Sultan C: Human prostatic cell line PNT1A, a useful tool for studying androgen receptor transcriptional activity and its differential subnuclear localization in the presence of androgens and antiandrogens. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001, 184:13-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newmark JR, Hardy DO, Tonb DC, Carter BS, Epstein JI, Isaacs WB, Brown TR, Barrack ER: Androgen receptor gene mutations in human prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992, 89:6319-6323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterziel H, Culig Z, Stober J, Hobisch A, Radmayr C, Bartsch G, Klocker H, Cato AC: Mutant androgen receptors in prostatic tumors distinguish between amino-acid-sequence requirements for transactivation and ligand binding. Int J Cancer 1995, 63:544-550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horoszewicz JS, Leong SS, Kawinski E, Karr JP, Rosenthal H, Chu TM, Mirand EA, Murphy GP: LNCaP model of human prostatic carcinoma. Cancer Res 1983, 43:1809-1818 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaighn ME, Shankar Narayan K, Ohnuki Y, Lechner JF, Jones LW: Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3). Invest Urol 1979, 17:16-23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stone KR, Mickey DD, Wunderli H, Mickey GH, Paulson DF: Isolation of a human prostate carcinoma cell line (DU 145). Int J Cancer 1978, 21:274-281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenton MA, Shuster TD, Fertig AM, Taplin ME, Kolvenbag G, Bubley GJ, Balk SP: Functional characterization of mutant androgen receptors from androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1997, 3:1383-1388 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan J, Sharief Y, Hamil KG, Gregory CW, Zang DY, Sar M, Gumerlock PH, deVereWhite RW, Pretlow TG, Harris SE, Wilson EM, Mohler JL, French FS: Dehydroepiandrosterone activates mutant androgen receptors expressed in the androgen-dependent human prostate cancer xenograft CWR22 and LNCaP cells. Mol Endocrinol 1997, 11:450-459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong CI, Kelce WR, Sar M, Wilson EM: Androgen receptor antagonist versus agonist activities of the fungicide vinclozolin relative to hydroxyflutamide. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:19998-20003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veldscholte J, Ris-Stalpers C, Kuiper GGJM, Jenster G, Berrevoets C, Claassen E, van Rooij HCJ, Trapman J, Brinkmann AO: A mutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor of human LNCaP cells affects steroid binding characteristics and response to anti-androgens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1990, 17:534-540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao XY, Boyle B, Krishman AV, Navone NM, Peehl DM, Feldman D: Two mutations identified in the androgen receptor of the new human prostate cancer cell line MDA PCa 2a. J Urol 1999, 162:2192-2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taplin ME, Bubley GJ, Shuster TD, Frantz ME, Spooner AE, Ogata GK, Keer HN, Balk SP: Mutation of the androgen receptor gene in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 1995, 332:1393-1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcelli M, Ittmann M, Mariani S, Sutherland R, Nigam R, Murthy L, Zhao Y, DiConcini D, Puxeddu E, Esen A, Eastham J, Weigel NL, Lamb DJ: Androgen receptor mutations in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2000, 60:944-949 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S, Hsieh ML, Zhu W, Klee GG, Tindall DJ, Young CY: Interactive effects of triiodothyronine and androgens on prostate cell growth and gene expression. Endocrinology 1999, 140:1665-1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cronauer MV, Nessler-Menardi C, Klocker H, Maly K, Hobisch A, Bartsch G, Culig Z: Androgen receptor protein is down-regulated by basic fibroblast growth factor in prostate cancer cells. Br J Cancer 2000, 82:39-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craft N, Shostak Y, Carey M, Sawyers CL: A mechanism for hormone-independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nat Med 1999, 5:280-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Truica CI, Byers S, Gelmann EP: Beta-catenin affects androgen receptor transcriptional activity and ligand specificity. Cancer Res 2000, 60:4709-4713 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harada S, Keller ET, Fujimoto N, Koshida K, Namiki M, Matsumoto T, Mizokami A: Long-term exposure of tumor necrosis factor alpha causes hypersensitivity to androgen and anti-androgen withdrawal phenomenon in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2001, 46:319-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scher HI, Kelly WK: Flutamide withdrawal syndrome: its impact on clinical trials in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 1993, 11:1566-1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laufer M, Sinibaldi VJ, Carducci MA, Eisenberger MA: Rapid disease progression after the administration of bicalutamide in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Urology 1999, 54:745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nieh PT: Withdrawal phenomenon with the antiandrogen casodex. J Urol 1995, 153:1070-1072 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Small PJ, Carroll PR: Prostate-specific antigen decline after casodex withdrawal: evidence for an antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome. Urology 1994, 44:790-792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haapala K, Hyytinen ER, Roiha M, Laurila M, Rantala I, Helin HJ, Koivisto PA: Androgen receptor alterations in prostate cancer relapsed during a combined androgen blockade by orchiectomy and bicalutamide. Lab Invest 2001, 81:1647-1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nessler-Menardi C, Jotova I, Culig Z, Eder IE, Putz T, Bartsch G, Klocker H: Expression of androgen receptor coregulatory proteins in prostate cancer and stromal-cell culture models. Prostate 2000, 45:124-131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muller JM, Isele U, Metzger E, Rempel A, Moser M, Pscherer A, Breyer T, Holubarsch C, Buettner R, Schule R: FHL2, a novel tissue-specific coactivator of the androgen receptor. EMBO J 2000, 19:359-369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Debes JD, Schmidt LJ, Huang H, Tindall DJ: p300 mediates interleukin-6-dependent transactivation of the androgen receptor. Proc AACR 2002, 43:161(Abstract) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]