Abstract

Placental apoptosis is increased in vivo in preeclampsia (PE) and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). The cause and pathological implications of this phenomenon are unknown. This study considers the apoptotic susceptibility of villous trophoblasts from normal, PE, and IUGR pregnancies. Cultured cytotrophoblasts (CTs) and an in vitro model of syncytialization were used. CTs were isolated from term placentas of 12 normal, 12 PE, and 12 IUGR pregnancies. Apoptosis was determined by terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL), Annexin V binding, and ADP:ATP ratios. Cells were stimulated with tumor necrosis factor-α/interferon-γ or reduced oxygen (<5 KPa). For CTs, ADP:ATP <1 correlates with Annexin V binding. For normal pregnancy, tumor necrosis factor-α and depleted oxygen significantly increased TUNEL, Annexin V binding and ADP:ATP in CTs and syncytiotrophoblasts (STs). Spontaneous apoptosis was similar between groups for both cell types. After stimulation, TUNEL and Annexin V binding of CTs were significantly raised in PE and IUGR as compared with normal pregnancy. After oxygen reduction, ADP:ATP in CTs and STs were significantly elevated in IUGR. TUNEL was also increased in STs in PE after oxygen depletion and was significantly raised in STs from IUGR pregnancies after stimulation with both agonists. This is the first description of enhanced apoptosis in isolated villous trophoblasts in PE and IUGR. These intrinsic differences may represent an important factor in the pathophysiology of these conditions.

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is crucial to the development and homeostasis of human tissues, including the human placenta. In combination with mitosis, apoptosis regulates the number of cells in any given tissue and therefore its size and function. In normal pregnancy, cytotrophoblasts (CTs) and syncytiotrophoblasts (STs) can be considered to be in a steady state, however it is likely that placental insults can alter this relationship, possibly by modulating trophoblast cell turnover. 1 Our previous investigations have demonstrated that trophoblast apoptosis is a normal event in placental aging, 2 but we have also shown elevated levels of placental apoptosis in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preeclampsia (PE). 3,4 As there is no fall in the incidence of proliferating cells, 5 it could be postulated that accelerated apoptosis may represent either a primary pathological event, or a secondary adaptation to maintain and optimize the syncytial barrier.

Although extensively studied in other systems, the mechanism and control of apoptosis in the human trophoblast is unclear. 6 Differences in the morphological features of cell death between CTs and STs, and their susceptibility to apoptosis in vitro, have suggested disparate apoptotic pathways in differentiated and undifferentiated cells. 7 For most experiments, we have used isolated cultured CTs and an in vitro model of syncytialization and we have demonstrated that trophoblast apoptosis can be induced by a number of physiological and nonphysiological agonists. 7 Of these the most pertinent in healthy pregnancy, PE, and IUGR are tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and conditions of depleted oxygen. 8-10 It is believed that these conditions can arise in the placenta as a result of placental underperfusion, oxidative stress, and inflammatory assault. In previous experiments, we and others, have shown that TNF-α stimulates apoptosis in villous CTs and STs via the TNF-α receptor, TNF-RI. 7,11 We have also shown, along with others, that TNF-α-induced apoptosis can be inhibited by epidermal growth factor (EGF) and to a lesser extent by platelet-derived growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and basic fibroblast growth factor. 12,13 Therefore, overall placental apoptosis occurs in the physiological context of excessive stimulation by death factors and inadequate protection by survival factors. Whether these survival factors can influence the apoptotic machinery directly or whether they act indirectly by regulating cell differentiation is not yet fully established.

By identifying and inducing apoptosis in CTs and STs in vitro, we have studied the apoptotic susceptibility of placental villous trophoblasts in healthy pregnancy and pregnancies complicated by PE and IUGR. In these experiments, we have compared spontaneous apoptosis and induced apoptosis in response to TNF-α and depleted oxygen. Measurements have been made using DNA fragmentation, phosphatidylserine expression and the ratios of ADP:ATP (a form of apoptotic recognition reliant on differences in mitochondrial output). The overall aim was to investigate whether variations in trophoblast responsiveness could explain the elevated levels of placental apoptosis in IUGR and PE.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The Local Ethics Committee gave approval for this work and participants gave informed consent. Twelve women with PE, 12 women with pregnancies complicated with IUGR, and 12 normal pregnant women were studied. PE was defined as a blood pressure of >140/90 mmHg on two or more occasions after the 20th week of pregnancy, in a previously normotensive woman in the presence of significant proteinuria (either >300 mg/L in a 24-hour collection or >2+ on a voided random urine sample in the absence of urinary tract infection). Women with essential hypertension and with medical complications such as diabetes and renal disease were excluded. IUGR was identified by antenatal ultrasound scans and confirmed after delivery by an individualized birth weight ratio below the 10th centile. The individualized birth weight ratio is relative to predicted birth weight and is calculated using independent coefficients for gestation at delivery, fetal sex, parity, ethnicity, maternal height, and booking weight. The individualized birth weight ratio enables a more accurate prediction of pregnancies ending in poor outcome than birth weight for gestational age alone. 14

CT Isolation

Unless otherwise stated all reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, UK.

Cells were isolated from whole term placentas taken from women at elective cesarean section. A CT-enriched population was isolated from placentas using a modified method of Kliman and colleagues. 15 In brief, membranes, connective tissues, and surfaces adjacent to decidua were removed and the remaining tissue digested with trypsin (0.25%) and DNase (0.2 mg/ml) in prewarmed Hanks’ balanced salt solution, containing 25 mmol/L of HEPES in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 30 minutes. The tissue fragments were allowed to settle and 25-ml aliquots of the supernatant were layered over 5 ml of newborn calf serum and centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature. The pelleted cells were then resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. The remaining tissue was subjected to the digestion procedure twice more, always with the addition of fresh trypsin-DNase solution each time. All resultant cell suspensions were pooled, centrifuged at 400 × g and resuspended in 6 ml of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. The cells were then divided in half and layered over discontinuous Percoll density gradients (3 ml 70%, 2 ml 60%, 2 ml 55%, 2 ml 50%, 2 ml 45%, 2 ml 40%, 2 ml 35%, 4 ml 30%, 2 ml 20%, and 2 ml 10% Percoll in Hanks’ balanced salt solution). The Percoll gradients were centrifuged at 1200 × g at room temperature for 30 minutes. The band of cells between 55% and 35% Percoll contained an enriched population of CTs. These cells were collected, washed once, and preserved in liquid nitrogen in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide in fetal bovine serum. For each experiment, cells were removed from frozen and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium:Ham’s F12 (1:1) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 25 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mmol/L glutamine, and antibiotics in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air incubator at 37°C.

Immunostaining

Adherent CTs were assessed for purity after 24 hours in culture. Cells were washed twice with warmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove nonadherent cells and fragments, then fixed with methanol for 10 minutes, washed twice again with PBS and then stained. The biological markers used were cytokeratin-7, which is expressed on trophoblasts but not other villous components, 16 vimentin that is expressed by mesenchymal cells, leukocyte common antigen (LCA/CD45) that identifies macrophages, and von Willebrand Factor that reacts with human endothelial cells and platelets. CTs were preincubated for 30 minutes in 20% goat serum in PBS, then incubated for 1 hour with either anti-human cytokeratin-7 (OV/TL1230; DAKO Ltd., High Wycombe, UK) diluted 1:50 (v/v) in 20% goat serum, anti-human vimentin (1:20, V9; DAKO Ltd.), anti-human LCA (1:10, T29/33; DAKO Ltd.), or anti-human von Willebrand Factor (1:25, F8/86; DAKO Ltd.). After incubations, cells were washed and incubated for 30 minutes with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG diluted 1:50 (v/v) in 10% goat serum. Cells were viewed with an inverted fluorescent microscope. The purity of the CTs within these adherent preparations was estimated from the proportion of cytokeratin-7-positive cells.

Syncytialization

Syncytialization was induced by treating CTs with 5 ng/ml of recombinant human EGF (PeproTech EC Ltd., London, UK). This procedure is known to enhance trophoblast differentiation in vitro. 17 After a period of 5 days, spent medium was aspirated and any remaining EGF was removed by washing. Syncytialization was confirmed by immunostaining of fixed cells with monoclonal anti-desmosomal protein and counterstaining with hematoxylin and by human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) production. All stimulation was conducted in the absence of EGF.

Stimulation

Agents and concentrations were chosen because of their apoptotic effects in previous studies 12,17 and their suggested relevance to PE and IUGR. Adherent populations of CTs and STs were prepared as outlined. After the initial culture of CTs for 24 hours, and 5 days in the case of STs, cells were further maintained in either media alone or in the presence of TNF-α with interferon gamma (IFN-γ) (10 ng/ml and 100 U/ml, respectively; PeproTech EC Ltd., London, UK) for 24 hours; or under reduced oxygen conditions, generated using Anaerocult bags (Merck, Poole, UK) for 48 hours at 37°C. After this incubation, oxygen concentrations (kPa) were determined using a Chiron/Diagnostics 840 blood gas analyzer.

hCG Measurements

The concentration of hCG in culture medium was assessed by quantitative immunoradiometric determination using a commercially available kit (hCG solid-phase component system; ICN Pharmaceuticals, Basingstoke, UK). The hCG assay uses the sandwich technique in which the solid phase binds the α subunit of hCG and a radiolabeled antibody in the liquid phase binds the β subunit.

Apoptosis Measurements

Apoptosis was assessed using Annexin V binding with propidium iodide (PI) staining, terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL), and the measurement of ATP and ADP levels. For Annexin V, PI, and ATP/ADP, cells were seeded at 100,000/well in 96-well cell-culture plates. For TUNEL measurements cells were seeded at 200,000/well.

TUNEL Assay

All TUNEL measurements were made on the FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, UK) using the FlowTACS Apoptosis Detection Kit (R&D Systems, Oxon, UK).

For cultured CTs, cells were first dissociated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution (2 mmol/L) with mild agitation, washed in fresh media, and resuspended in 100 μl of freshly prepared 3.7% paraformaldehyde solution. After a 10-minute incubation at room temperature, the cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 minutes and the fixative removed. The cells were washed once with 200 μl of PBS and then resuspended in 100 μl of permeabilization solution for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then centrifuged again, resuspended in 25 μl of the labeling reaction mixture, and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of stop buffer and the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 25 μl of diluted streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate. After incubation for 10 minutes in the dark, the cells were centrifuged, resuspended in 300 μl of PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Negative controls were set by resuspending fixed and permeabilized cells in 50 μl of label solution in the absence of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. Positive controls were included; washed and permeabilized cells were resuspended in 25 μl of nuclease solution for 30 minutes at 37°C before being labeled.

For STs, TUNEL analysis was performed on isolated nuclei using the method of Garcia-Lloret and colleagues. 12 STs were washed twice in PBS before the addition of 200 μl of 2× Krishan buffer (0.2% Na citrate, 0.2% Igepal CA-630, 40 μg/ml RNase, pH 7.4). Culture plates were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C and the lysates were aspirated and transferred to Eppendorf tubes. An equal volume of 70% ethanol was then added and the tubes were allowed to stand on ice for 5 minutes. Isolated nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 800 × g, washed once in 500 μl of 70% ethanol, once in 500 μl of PBS, and finally resuspended in 25 μl of the labeling reaction mixture. Further TUNEL labeling was conducted as outlined above.

Annexin V and PI Staining

During early apoptosis, a loss of membrane asymmetry occurs when phosphatidylserine is exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. Annexin V will preferentially bind to phosphatidylserine and can therefore be used as an early indicator of apoptosis. In addition, PI can be used to assess plasma membrane integrity and cell viability. PI fluoresces red when bound to DNA or double-stranded RNA, but is excluded from cells with intact plasma membranes. An in situ Apoptosis Detection Kit was used for Annexin V binding and PI staining (R&D Systems). Cultured CTs in each well of a 96-well microtiter plate, (Corning Costar, High Wycombe, UK) were washed twice in fresh media, dissociated as described above and resuspended in 80 μl of binding buffer (10 mmol/L Hepes, 140 mmol/L sodium chloride, 2.5 mmol/L calcium chloride, pH 7.4). To each cell suspension was added 10 μl of fluorescein-conjugated Annexin V (10 μg/ml) and 10 μl of PI reagent (50 μg/ml). The cells were mixed and incubated in the dark for 15 minutes at room temperature. At the end of the incubation, a further 400 μl of binding buffer was added and the cells were analyzed immediately by flow cytometry. Control tubes of unstained cells, cells stained with PI alone, and cells stained with Annexin V, were included to set flow cytometric compensation.

Assay of ATP and ADP

Direct and indirect measurements of ATP and ADP were made using the bioluminescence Apoglow Kit (LumiTech Ltd., Nottingham, UK). For these experiments, cells were cultured in clear-bottomed white-walled 96-well culture plates (Corning Costar) and the bases covered before readings were taken. Nucleotides were first released from the cultured cells by addition of an equal volume (in this case 100 μl) of somatic cell nucleotide-releasing reagent. This releasing reagent also contains the luciferin-luciferase nucleotide-monitoring reagent. The ATP levels were then measured using the luminometer (1450 Microbeta jet; EG & G Wallac Ltd., Milton Keynes, UK) and expressed as the number of relative light units (RLU). The ATP signal was allowed to decay for 10 minutes to a steady state. After 10 minutes the ADP in the wells was converted to ATP by the addition of 20 μl of ADP-converting reagent. An immediate reading was taken to determine the baseline ADP RLU (ADP 0). A third reading was taken after 5 minutes incubation to allow for conversion of ADP to ATP (ADP 5). Finally, the ratio of ADP:ATP was calculated from these three readings as follows: (ADP 5 − ADP 0) ÷ ATP.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise stated, statistical significance of difference for normally distributed data were determined using a Student’s t-test (with or without a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). Normal distribution was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk significance level normality test and results are presented as means and standard errors of the means (±SEM), with the data considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Participants

The median values and ranges for participant demographics are given in Table 1 ▶ . No differences were established between pregnant groups for maternal age, gravidity, or parity. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were significantly higher at sampling in women with PE compared with normal controls. Gestational age at delivery and individualized birth weight ratio values were lower in PE and IUGR—statistical significance was only reached in the case of IUGR.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Pregnancy | PE | IUGR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age | 30 (40–26) | 29 (40–20) | 31 (40–19) |

| Gravidity | 2 (8–1) | 3 (6–1) | 3 (4–1) |

| Parity | 1 (4–0) | 0 (3–0) | 1 (2–0) |

| Sample BP | |||

| Systolic (mmHg) | 120 (140–110) | 158 (195–150)* | 140 (150–107) |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | 72 (80–70) | 100 (110–90)* | 80 (105–64) |

| Gestation (weeks) | 38 (35–40) | 35 (31–38) | 33 (27–35)* |

| IBR | 62 (94–11) | 18 (99–3) | 4 (9–0)* |

Results represented as medians (ranges) (*P < 0.01 Mann-Whitney U-test).

The purity of CTs in culture was 90%, with a range of 85 to 100%. All contaminating cells were vimentin-positive only. Between 30% and 65% of the cells adhered to tissue culture surfaces after overnight incubation before initiation of the experiments (45 ± 9%, normals; 54 ± 12%, PE; 47 ± 8%, IUGR). Contamination by leukocytes and endothelial cells was negligible. Before culturing, enriched CT viabilities were 76% ± 4%. After 5 days in the presence of EGF, CTs were seen to form multinucleated syncytia. These differentiated cells were observed by light microscopy, showed a reduction in staining for desmosomal protein, gave a significant increase in hCG production (from 569 ± 194 to 3639 ± 1739 mIU/5 × 105cells/hour) and could also be identified from cytokeratin-7 staining as previously described. 18 A significant decrease in pO2 was recorded in the media of cells cultured in Anaerocult bags (normoxic, 23.6 (22.1 to 25.2) kPa; reduced oxygen, 4.9 (3.9 to 5.8) kPa (P < 0.05).

TUNEL Assay

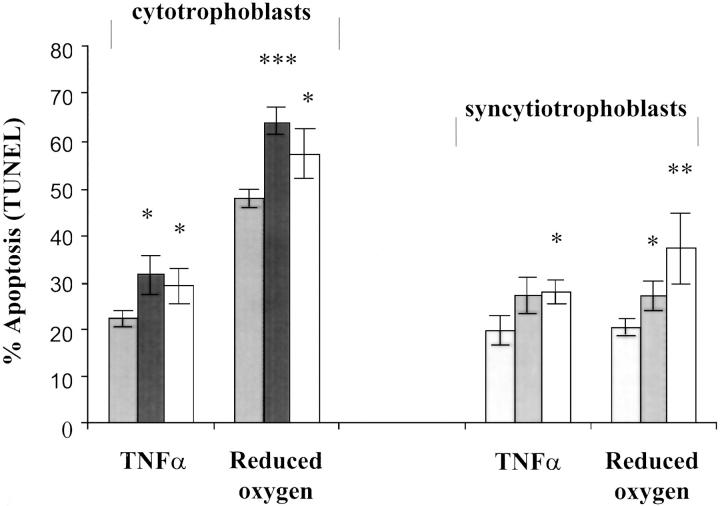

All TUNEL results are presented in Figure 1 ▶ . For normal pregnancy, unstimulated values of apoptosis in CTs and STs were 12.0 ± 1% and 6.1 ± 1.1%, respectively. Cytotoxic agents increased these measurements to 22.4% and 20.1% in the case of TNF-α and to 47.9% and 20.9% in the case of oxygen depletion. After TNF-α induction and oxygen depletion, TUNEL positivity was significantly elevated in CTs from PE and IUGR above those of normal pregnancy. Apoptosis was increased in PE to 31.7% (TNF-α) and 64.5% (reduced oxygen), and in IUGR to 29.4% (TNF-α) and 57.1% (reduced oxygen). Although increases in response to diminished oxygen were less marked in STs than CTs, apoptosis was still significantly enhanced over normal pregnant controls. For IUGR, TNF-α and oxygen depletion raised these levels to 28.4% and 37.3%. For PE, apoptotic levels were increased to 27.3% after oxygen reductions. Basal apoptosis for CTs and STs were unchanged between all study groups.

Figure 1.

The effect of TNF-α/IFN-γ and oxygen depletion on TUNEL analysis of CTs and STs from the placentas of normal pregnancies and pregnancies complicated by PE and IUGR. Light gray columns, normal pregnancy; dark gray columns, PE; white columns, IUGR. Results (means ± SEM) expressed as percent TUNEL +ve nuclei. Statistical significance from untreated controls: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

Annexin V Binding

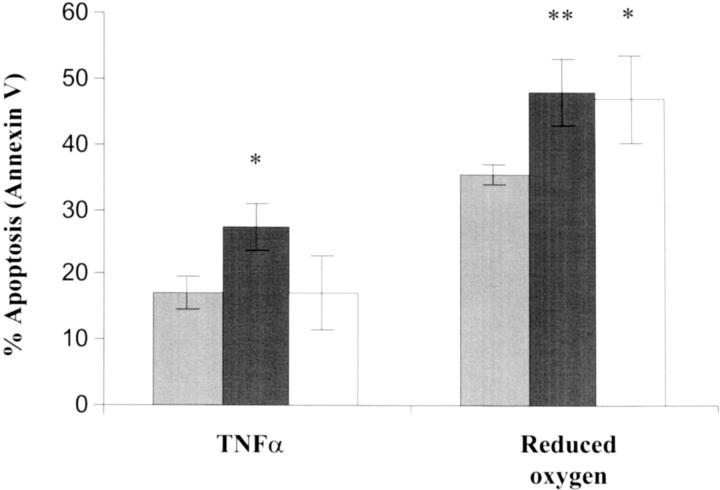

Baseline apoptosis for normal CTs, as measured by Annexin V binding, was increased in response to TNF-α and oxygen depletion from 4.0 ± 2.8% to 17.1 ± 2.4% and 35.1 ± 1.6%, respectively (Figure 2) ▶ . Again, baseline values between PE (7.3 ± 1.1%), IUGR (6.3 ± 0.4%), and normal pregnant groups were not significantly affected. For PE and IUGR, Annexin V binding of CTs was significantly increased above normals in response to both TNF-α and oxygen depletion. This is illustrated in Figure 2 ▶ . For PE, apoptosis was elevated above normal to 27.2% in response to TNF-α and to 47.9% in response to oxygen reduction. For IUGR, these levels were significantly higher at 46.6% after oxygen depletion but were comparable to the normal pregnant group in response to TNF-α.

Figure 2.

The effect of TNF-α/IFN-γ and oxygen depletion on Annexin V binding potential of CTs from the placentas of normal pregnancies and pregnancies complicated by PE and IUGR. Light gray columns, normal pregnancy; dark gray columns, PE; white columns, IUGR. Results (means ± SEM) expressed as percent apoptosis. Statistical significance from untreated controls: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Differentiation of CTs in Culture

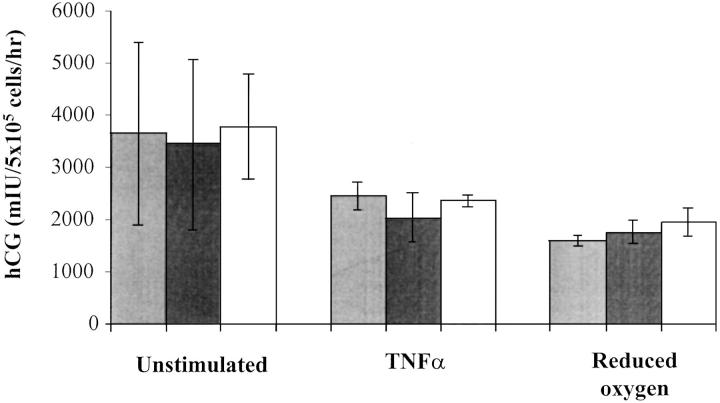

Syncytialization was confirmed in CT cultures after 5 days by measuring the production of hCG. Figure 3 ▶ shows that there were no significant differences in hCG release between control cultures and those of PE and IUGR before stimulation. After treatment with TNF-α/IFN-γ and 3% O2, hCG production fell in the control group by 32.5% and 55.6%, respectively. Although reduced, these levels were again statistically similar to those of PE and IUGR.

Figure 3.

The effect of TNF-α/IFN-γ and oxygen depletion on the differentiation of CTs in culture as measured by hCG production. Light gray columns, normal pregnancy; dark gray columns, PE; white columns, IUGR. Results (means ± SEM) expressed for 5 × 105 cells throughout a 6-day culture period.

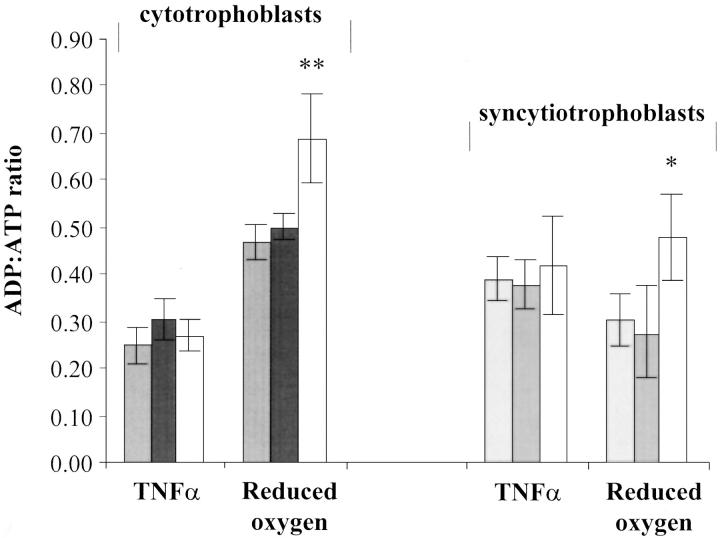

Assay of ATP and ADP

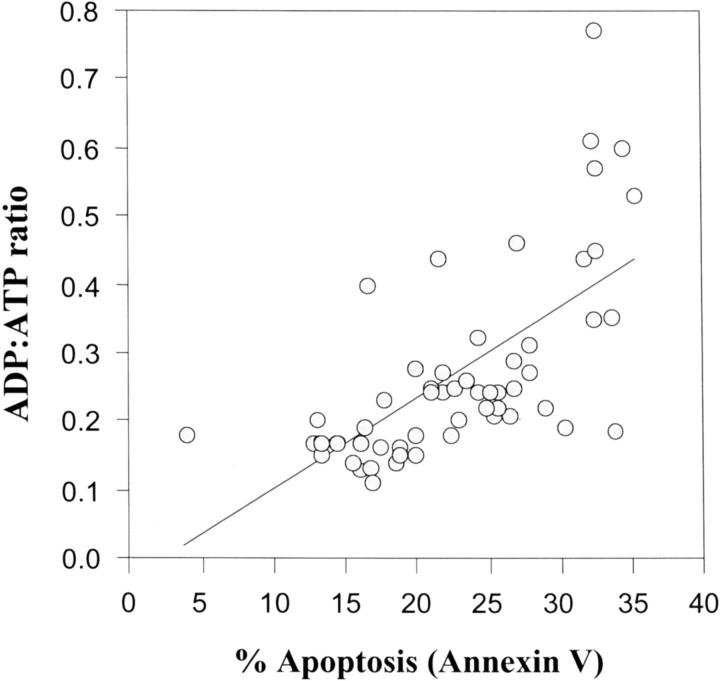

As previously reported (and reproduced by permission), 7 ADP:ATP ratios of less than 1 correlate significantly with Annexin V binding of CTs on the flow cytometer (Figure 4) ▶ . In response to TNF-α, ADP:ATPs were raised in normal CTs from 0.19 ± 0.03 to 0.25 ± 0.04 and in normal STs from 0.19 ± 0.04 to 0.39 ± 0.04 (Figure 5) ▶ . By reducing oxygen in culture, ADP:ATP values were raised in CTs and STs to 0.47 ± 0.06 and 0.30 ± 0.06, respectively. After oxygen reductions, the elevations in the ratios of both CTs and STs were significantly higher in the IUGR preparations (0.69 ± 0.09 and 0.48 ± 0.09 for CTs and STs, respectively) as compared to the normal pregnant preparations. No significant differences between PE and normal pregnant cells were found.

Figure 4.

The correlation between the bioluminescent measurement of CT ADP:ATP and the percent apoptosis of CTs as measured by Annexin V binding on the flow cytometer. The correlation coefficient for linear association was r = 0.65 (P < 0.001, Pearson two-tailed significance). Data reproduced by permission (International Federation of Placenta Associations) (Crocker and colleagues 7 ).

Figure 5.

The effect of TNF-α/IFN-γ and oxygen depletion on the ADP:ATP ratios of CTs and STs from the placentas of normal pregnancies and pregnancies complicated by PE and IUGR. Light gray columns, normal pregnancy; dark gray columns, PE; white columns, IUGR. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Discussion

The etiology of IUGR and PE is unclear, however placental dysfunction is considered a common underlying cause in both conditions. It has been suggested that these placentas display altered cell kinetics 19 and also, in the case of PE, an inappropriate release of harmful material into the maternal circulation. 20 As already described, we and others have reported an increase in placental apoptosis in both PE and IUGR. 2,3,21 Through ex vivo observations, we have shown this process to predominate in the syncytium, where it is believed to reflect a long and extended program of nuclear and cellular decline. 4 In more recent studies, apoptosis has been detected in the undifferentiated CTs within the placental villous. 4 These observations imply a second level of regulation; one additional to syncytial turnover, but one which may hold equal importance for trophoblast turnover and syncytial integrity.

In this study, we have investigated the in vitro responses of isolated CTs and STs from the third trimester of pregnancy. These are the principal cells of late gestation and constitute an important component in maternal and fetal exchange. Although in vitro models can never mimic the in vivo environment, they have been used here to investigate trophoblast responses to induced and spontaneous apoptosis. As might be expected, levels of recorded apoptosis were higher than those previously reported ex vivo; 22 nevertheless, background levels appear consistent between assays and values are similar to those reported in other studies. 12,17 TUNEL was elevated in all cell types, under conditions of both depleted oxygen and TNF-α—two situations strongly relating to IUGR and PE. 8-10,23 Although responses were more pronounced in CTs, particularly through oxygen reduction, similarities in response to TNF-α indicate a direct transfer of functional receptors during differentiation. The apoptotic machinery of CTs therefore remains intact, regardless of syncytialization.

In general terms, TUNEL and Annexin V measurements appear consistent with those of ADP:ATP. In most cases induced apoptosis, either through receptor-mediated TNF-α or exposure to restricted oxygen, was elevated in cells from pregnancies complicated by PE and IUGR. Certain variations between assays may be explained by differences in assay sensitivity and the particular stage at which apoptosis was detected. Similarities in baseline values would reinforce the disparity in stimulus-dependent activity and therefore point to a form of apoptotic priming in vivo.

Morphological and biochemical differentiation of CTs was shown to influence apoptotic outcome, however this was not instrumental in the observed attenuations in IUGR and PE. Although care was taken to match patients and to include a range of techniques to confirm apoptosis, the gestational ages of IUGR patients could not be aligned with those of normal pregnancy. Moreover, Annexin V measurements could not be extended to STs, because single cells are necessary for flow analysis and exposure of phosphatidylserine has been previously associated with syncytial formation in vivo. 24

These recorded elevations in PE and IUGR may therefore reflect the placental environment from which these cells were derived and/or may be an indication of more intrinsic variations within the cells themselves. All CTs were isolated from whole and not partial placentas and as such would include tissues affected by necrosis, infarction, and calcification. As the incidence of these features is often exaggerated in compromised pregnancies, elevated apoptosis could be a symptom of tissue quality and/or the previous exposure of the cells to adverse conditions in situ. Evidence for spontaneous apoptosis, within our experiments, does not support the idea of postnatally defective or necrotic tissue. We would therefore promote the idea that exposure to physiological death and/or survival factors in vivo, has a mechanistic influence on placental trophoblasts, one that leads to aberrant apoptosis in vitro.

Although highly conserved, death pathways are now increasingly recognized as cell type- and stimulus-specific. At present little is known about these pathways in placental trophoblasts, either before or after morphological transformation. The expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic components in these cells, such as procaspase 3 and caspase 3, 25 Bcl-2, 26 Bax, and Bak, 27 indicate the presence of many common apoptotic regulators. Although widely studied in other systems, the relative importance of these elements and their interplay in single cell trophoblasts and the more complicated multinucleated syncytium is presently unknown.

The ratio of homodimers to heterodimers within the Bcl-2 family has been proposed as a determinant of cell fate, the so-called “rheostat model.” 28 With regard to CTs, apoptosis in the preeclamptic placenta has been related to the relative expression of proapoptotic Mtd and anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 (Caniggia I and colleagues, unpublished data). Both CTs and STs are shown to express Mcl-1, 25 however EGF is believed to promote survival by shifting the balance in favor of this anti-apoptotic regulator. 29 Evidence for proto-oncogene management of trophoblast death is therefore growing, and placental exposure to certain exogenous factors may at least be one explanation for our recorded differences in apoptotic susceptibility. Similarities in the amplitude of our modified responses, suggests that trophoblast regulation is not exclusively receptor mediated or initiator caspase-dependent. To elucidate these apoptotic differences further, our future work will concentrate on the interactions of trophoblast mitochondria with the recognized Bcl-2 family members.

In conclusion, this is the first description of functional variations in isolated cells from the placentas of compromised pregnancies. To replicate physiological conditions, work is currently underway using placental explants, whereby interactions and spatial arrangements of villous cells remain intact. 30 Although our recorded differences in trophoblast apoptosis may be a reflection of unfavorable conditions in the placenta, it is exciting to speculate, that in certain cases, placental CTs may be predisposed to exaggerated cell death and altered placental capacity.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Ian Crocker, Maternal and Fetal Health Research Centre, St. Mary’s Hospital, Whitworth Park, Manchester, United Kingdom M13 OJH. E-mail: ian.crocker@man.ac.uk.

Supported by the Medical Research Council and Tommy’s, the Baby Charity.

References

- 1.Mayhew TM, Leach L, McGee R, Ismail WW, Myklebust R, Lammiman MJ: Proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis in villous trophoblast at 13–41 weeks of gestation (including observations on annulate lamellae and nuclear pore complexes). Placenta 1999, 20:407-422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SC, Baker PN, Symonds EM: Placental apoptosis in normal human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997, 177:57-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung DN, Smith SC, To KF, Sahota DS, Baker PN: Increased placental apoptosis in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001, 184:1249-1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SC, Baker PN, Symonds EM: Increased placental apoptosis in intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997, 177:1395-1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith SC, Price E, Hewitt MJ, Symonds EM, Baker PN: Cellular proliferation in the placenta in normal human pregnancy and pregnancy complicated by intrauterine growth restriction. J Soc Gynecol Invest 1998, 5:317-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy R, Nelson DM: To be, or not to be, that is the question. Apoptosis in human trophoblast. Placenta 2000, 21:1-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crocker IP, Barratt S, Kaur M, Baker PN: The in-vitro characterization of induced apoptosis in placental cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts. Placenta 2001, 22:822-830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyborne KD, Witkin SS, McGregor JA: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in midtrimester amniotic fluid is associated with impaired intrauterine fetal growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992, 167:920-925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad KP, Miles TM, Benyo DF: Circulating levels of immunoreactive cytokines in women with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 1998, 40:102-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyall F, Bulmer JN, Duffie E, Cousins F, Theriault A, Robson SC: Human trophoblast invasion and spiral artery transformation: the role of PECAM-1 in normal pregnancy, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:1713-1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yui J, Hemmings D, Garcia-Lloret M, Guilbert LJ: Expression of the human p55 and p75 tumor necrosis factor receptors in primary villous trophoblasts and their role in cytotoxic signal transduction. Biol Reprod 1996, 55:400-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Lloret MI, Yui J, Winkler-Lowen B, Guilbert LJ: Epidermal growth factor inhibits cytokine-induced apoptosis of primary human trophoblasts. J Cell Physiol 1996, 167:324-332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SC, Francis R, Guilbert L, Baker PN: Growth factor rescue of cytokine mediated trophoblast apoptosis. Placenta 2002, 23:322-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilcox MA, Johnson IR, Maynard PV, Smith SJ, Chilvers CE: The individualised birthweight ratio: a more logical outcome measure of pregnancy than birthweight alone. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1993, 100:342-347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kliman HJ, Nestler JE, Sermasi E, Sanger JM, Strauss JF, III: Purification, characterization, and in vitro differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from human term placentae. Endocrinology 1986, 118:1567-1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haigh T, Chen C, Jones CJ, Aplin JD: Studies of mesenchymal cells from 1st trimester human placenta: expression of cytokeratin outside the trophoblast lineage. Placenta 1999, 20:615-625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy R, Smith SD, Chandler K, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM: Apoptosis in human cultured trophoblasts is enhanced by hypoxia and diminished by epidermal growth factor. Am J Physiol 2000, 278:C982-C988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crocker IP, Strachan BK, Lash GE, Cooper S, Warren AY, Baker PN: Vascular endothelial growth factor but not placental growth factor promotes trophoblast syncytialization in vitro. J Soc Gynecol Invest 2001, 8:341-346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paine CG: Observations on placental histology in normal and abnormal pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 1957, 64:688-672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redman CW, Sargent IL: Placental debris, oxidative stress and pre-eclampsia. Placenta 2000, 21:597-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erel CT, Dane B, Calay Z, Kaleli S, Aydinli K: Apoptosis in the placenta of pregnancies complicated with IUGR. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001, 73:229-235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allaire AD, Ballenger KA, Wells SR, McMahon MJ, Lessey B: Placental apoptosis in preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2000, 96:271-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holcberg G, Huleihel M, Sapir O, Katz M, Tsadkin M, Furman B, Mazor M, Myatt L: Increased production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha TNF-alpha by IUGR human placentae. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001, 94:69-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler RR, Ng AK, Rote NS: Monoclonal antiphosphatidylserine antibody inhibits intercellular fusion of the choriocarcinoma line, JAR. Biol Reprod 1995, 53:905-910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huppertz B, Frank HG, Kingdom JC, Reister F, Kaufmann P: Villous cytotrophoblast regulation of the syncytial apoptotic cascade in the human placenta. Histochem Cell Biol 1998, 110:495-508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axt-Fliedner R, Friedrich M, Kordina A, Wasemann C, Mink D, Reitnauer K, Schmidt W: The immunolocalization of Bcl-2 in human term placenta. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2001, 28:144-147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratts VS, Tao XJ, Webster CB, Swanson PE, Smith SD, Brownbill P, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Tilly JL, Nelson DM: Expression of BCL-2, BAX and BAK in the trophoblast layer of the term human placenta: a unique model of apoptosis within a syncytium. Placenta 2000, 21:361-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oltvai ZN, Korsmeyer SJ: Checkpoints of dueling dimers foil death wishes. Cell 1994, 79:189-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leu CM, Chang C, Hu C: Epidermal growth factor (EGF) suppresses staurosporine-induced apoptosis by inducing mcl-1 via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Oncogene 2000, 19:1665-1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siman CM, Sibley CP, Jones CJ, Turner MA, Greenwood SL: The functional regeneration of syncytiotrophoblast in cultured explants of term placenta. Am J Physiol 2001, 280:R1116-R1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]