Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (EBV-AHS) is often associated with fatal infectious mononucleosis or T-cell lymphoproliferative diseases (LPD). To elucidate the true nature of fatal LPD observed in Herpesvirus papio (HVP)-induced rabbit hemophagocytosis, reactive or neoplastic, we analyzed sequential development of HVP-induced rabbit LPD and their cell lines. All of the seven Japanese White rabbits inoculated intravenously with HVP died of fatal LPD 18 to 27 days after inoculation. LPD was also accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) in five of these seven rabbits. Sequential autopsy revealed splenomegaly and swollen lymph nodes, often accompanied by bleeding, which developed in the last week. Atypical lymphoid cells infiltrated many organs with a “starry sky” pattern, frequently involving the spleen, lymph nodes, and liver. HVP-small RNA-1 expression in these lymphoid cells was clearly demonstrated by a newly developed in situ hybridization (ISH) system. HVP-ISH of immunomagnetically purified lymphoid cells from spleen or lymph nodes revealed HVP-EBER1+ cells in each CD4+, CD8+, or CD79a+ fraction. Hemophagocytic histiocytosis was observed in the lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, and thymus. HVP-DNA was detected in the tissues and peripheral blood from the infected rabbits by PCR or Southern blot analysis. Clonality analysis of HVP-induced LPD by Southern blotting with TCR gene probe revealed polyclonal bands, suggesting polyclonal proliferation. Six IL-2-dependent rabbit T-cell lines were established from transplanted scid mouse tumors from LPD. These showed latency type I/II HVP infection and had normal karyotypes except for one line, and three of them showed tumorigenicity in nude mice. These data suggest that HVP-induced fatal LPD in rabbits is reactive polyclonally in nature.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is one of the human herpesviruses and is a member of the γ herpesvirus family (lymphocryptovirus). EBV was the first tumor virus identified from cultured lymphoblasts of Burkitt’s lymphoma, 1 and its potential role as a causative agent of EBV-associated tumors has been an important subject of investigation for approximately the last 40 years. EBV is widely dispersed in the human population. Most adults who remain asymptomatic are persistently infected and have antibodies to the virus. EBV is classically associated with infectious mononucleosis (IM), Burkitt’s lymphoma in equatorial Africa, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. 2 The range of EBV-associated diseases has recently expanded to include oral hairy leukoplakia from AIDS patients, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, some settings of B-cell or T-cell lymphoma, Ki-1 lymphoma, lymphoproliferative diseases (LPD) of primary and secondary immunodeficiency, lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the stomach, thymus, lung and salivary gland, 3-7 and EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (EBV-AHS). 8-13

Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an unusual syndrome characterized by common clinicopathological features such as fever, skin lesions, lung infiltrates, hepatosplenomegaly with jaundice and liver dysfunction, pancytopenia, and coagulopathy, and pathological findings of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow and other tissues. HPS may be diagnosed in association with malignant, genetic, or autoimmune diseases, but it is also prominently linked with EBV infection. 14

Human EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (EBV-AHS) is a distinct disease characterized by high mortality, while patients with non-viral pathogens-associated HPS often respond to treatment of the underlying infection. Rare cases of primary EBV infection develop into fatal IM, 13,15 which is commonly accompanied by virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS), whereas infectious mononucleosis is usually a self-limiting disease. 13 EBV-AHS is also associated not only with B-cell LPD, most cases of X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP) 13 and sporadic or familial HPS, 16 but also with T-cell LPD in patients with fatal childhood T-cell LPD, 10-12 chronic active EBV infection, 17 and EBV-infected T-cell lymphoma. 9,18 EBV-associated natural killer cell proliferation with fatal VAHS has been reported in a Vietnamese case. 19 Increased serum levels of many cytokines, including soluble interleukin (IL)- 2, IL-1, IL-3, IL-6, macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), interferon-γ, prostaglandins, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), have also been reported. 11,13,14,20 Although EBV-AHS in previously healthy children or young adults is usually considered a reactive process, EBV-AHS mimics T-cell lymphoma biologically and the clonal cytogenetic abnormalities that can emerge should be considered a malignant entity and treated with intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. 10,11,19,21-23 A large series of cytogenetic and molecular studies is needed to clarify the true nature of this fatal disease. Many cases of HPS have been associated with viral infections, particularly EBV, but the pathogenesis of the syndrome still remains unclear. The exact nature of EBV-AHS, whether it is an infectious process or a neoplastic disease, as well as the role of EBV in development of LPD and VAHS, remains to be clarified.

Herpesvirus papio (HVP) is a lymphocryptovirus from baboons that is similar to EBV both biologically and genetically. 24-27 The epidemiology of HVP infection in baboons closely parallels that of EBV infection in humans 28 and HVP can immortalize B lymphocytes from humans and various monkeys. HVP also has the potential to induce B-cell LPD in the cotton-topped marmoset, a New World monkey. 24

We have previously reported the first animal in vivo model of EBV-associated fatal HPS in which fatal LPD with HPS frequently develops in New Zealand White rabbits inoculated with HPV. 29 In this study, we not only confirm the similar HVP-induced clinicopathological features in Japanese White rabbits, but also describe several important new findings on the nature of HVP-induced rabbit fatal LPD. These were disclosed by sequential autopsy analysis, identification of HVP-infected cell phenotypes using a newly developed HVP-EBER1-ISH system and immunomagnetically purified cells, and characterization of HVP-infected cell lines established from transplanted scid mice tumors of HVP-induced rabbit LPD. A comparative analysis between this rabbit model and human EBV-AHS, EBV-associated lymphomas, or simian EBV-like virus-induced rabbit lymphomas will be discussed herein.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Culture

An HVP-producing baboon lymphoblastoid cell line (594S), a human EBV-producing marmoset cell line (B95–8), and an HTLV-I-producing rabbit cell line (Ra-1) were used.

Inoculation of Cell-Free Virion Pellets from Culture Supernatants

Specific-pathogen-free normal Japanese White rabbits (2 to 3 kg in weight) obtained from Shimizu Laboratory Supplies (Kyoto, Japan) were inoculated intravenously with the cell-free virion pellets from 200 ml supernatants of a 594S, B95–8, or Ra-1 culture, prepared as described below. Culture supernatants obtained from 594S culture (5 × 105 cells/ml) were first centrifuged at 8000 × g for 30 minutes to remove cell debris (Himac CR20, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and then at 100,000 × g for 60 minutes to obtain the pellets (Hitachi Himac Centrifuge SCP85H). These pellets were stocked in a freezer at −80°C until the experiments were carried out. The stocked pellets from the supernatant (3400 ml) were mixed and then divided into 17 crude virus fractions (each fraction was consistent with pellets from the 200-ml supernatant) (Table 1) ▶ .

Table 1.

Summary of Herpesvirus Papio (HVP)-Infected JW Rabbit Studies

| Rabbit name | Inoculum (intravenous) | Anti-VCA IgG titer (days) | Survival after inoculation (days) | Macroscopical bleeding sites | LPD (spleen) | LPD (LN) | LPD (liver) | HP | Transplanted scid tumor | Cell lines obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J2 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ×640 (21) | 27d, died | Nose, LN, ascites | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ne | ne |

| J3 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ×1280 (21) | 24d, died | Lung, LN, ascites | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | ne | ne |

| J4 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ×640 (21) | 26d, died | Nose | +++ | +++ | +++ | ne | ne | |

| J9 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ×1280 (21) | 26d, died | Lung, LN, spleen | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ne | ne |

| J8 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ×2560 (21) | 23d, died | LN, ascites | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | ne | ne | |

| J24 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ×640 (21) | 25d, died | Nose, lung, LN | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ne | ne |

| J7 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 24d, killed for culture | Ear, LN | ++++ | +++ | +++ | + | 2/4 | 0 |

| J10 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 22d, killed for culture | Nose, LN | ++++ | +++ | +++ | + | 4/4 | 2 |

| J11 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 18d, cultured 1 hour after death | Nose, lung | ++++ | ++ | +++ | + | 7/8 | 2 |

| J12 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 22d, killed for culture | − | ++ | +++ | + | 0/4 | 0 | |

| J13 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 19d, killed for culture | Nose, LN | ++++ | +++ | +++ | + | 4/4 | 2 |

| J32 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 17d, killed for MACS | − | + | − | − | ne | ne | |

| J30 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 18d, killed for MACS | − | ++ | + | + | ne | ne | |

| J29 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 19d, killed for MACS | − | +++ | + | ++ | ne | ne | |

| J31 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 20d, killed for MACS | − | ++ | + | + | ne | ne | |

| J23 | Virion pellets of 594S supe (200ml) | ne | 21d, killed for MACS | Nose, LN | ++++ | +++ | +++ | + | ne | ne |

| JW (3) | Virion pellets of B95-8 supe (200ml) | ×160–320 (21) | 90d, killed | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | ne | ne |

| JW (3) | Virion pellets of Ra-1 supe (200ml) | <×10 (21) | 90d, killed | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | − (0/3) | ne | ne |

JW rabbit, Japanese White rabbit; 594S, HVP-producing cell line; LPD, lymphoproliferative disease; LN, lymph node; HP, hemophagocytosis; transplanted scid tumor, transplanted rabbit LPD tumor in scid mice; 27d, 27 days; ne, not examined.

Antibody Responses to Viral Capsid Antigen (VCA) of EBV or HVP and Laboratory Examination in Rabbits

The titers of anti-VCA-IgG in pre- and post-inoculation reserved sera from rabbits were retrospectively examined by an indirect immunofluorescence (IF) test using the P3HR-1 cell line as a standard antigen of VCA and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cappel, West Chester, PA) as a secondary antibody.

Morphological Examination

Six HVP-infected rabbits were observed till their death. Other HVP-infected rabbits with or without bleeding tendency were killed by intravenous inoculation of excess pentobarbital sodium (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) for primary culture or immunomagnetic purification of lymphocytes. All three control animals inoculated with human EBV were sacrificed at the 90 days post-inoculation observation period. The organs including the spleen, liver, lymph nodes, lungs, thymus, kidneys, bone marrow, heart, and gastrointestinal tract were examined macroscopically and microscopically.

Establishment of Tumor Cell Lines and Chromosomal Analysis

The establishment of cell lines was attempted from the spleen, lymph nodes, or peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) of five HVP-infected rabbits. Normal-appearing spleens and PBL from one rabbit without LPD were also cultured as controls. Cells from the peripheral blood or spleen were allowed to grow in plastic tissue flasks in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics, and they were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2). Half of the medium was replenished every 3 to 4 days.

The cell line establishment was also challenged repeatedly from the serially transplanted tumors of HVP-induced rabbit LPD in severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mice (CB17/Icr-scid/scid Jcl, CLEA Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Some media for the primary culture from transplanted scid mouse tumors were supplemented with recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2, 500 IU/ml; Shionogi Pharmaceutical Inc., Osaka, Japan). A chromosomal analysis of the rabbit LPD lesions and the established lymphoid cell lines was performed by the standard G-banding technique.

Phenotypic Analysis of HVP-Induced LPD and Cell Lines

Tissues samples from rabbit LPD induced by HVP (594S) inoculation were immunostained by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) method (Immuno Mark Biotin Avidin Universal Kit; ICN Biochemical, Costa Mesa, CA) or the peroxidase antiperoxidase (PAP) method using antibodies to rabbit CD45, CD5, CD4, MHC class II DQ (Serotec, Oxford, England), rabbit CD8, CD25, CD79a (Spring Valley Laboratories Inc., Woodbine, MD), RT1, RT2 (antibodies to rabbit T cells, Cedarlane Laboratories, Ontario, Canada), or RABELA (rabbit bursal equivalent to lymphocyte antisera, Cedarlane Laboratories). For flow cytometry analysis of cell lines, FITC-labeled rabbit anti-mouse IgG antibody (DAKO-Japan, Kyoto, Japan) was used as a secondary antibody. Fluorescence was measured immediately by flow cytometry using FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Immunomagnetic Purification

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation using lymphocyte separation medium (ICN/Cappel, Aurora, OH). For magnetic cell sorting (MACS) separation, PBMC were labeled by incubating with primary mouse IgG antibody (anti-rabbit CD4, -rabbit CD8, or -rabbit CD79a) for 30 minutes. Cells were washed twice with PBS/0.5% BSA. Subsequently, cells were magnetically labeled with goat anti-mouse IgG MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for 15 minutes at 10°C and then separated by an immunomagnetic procedure incorporating the MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec).

Detection of EBV Genome in 594S Cells, HVP-Induced Rabbit LPD and Their Cell Lines

HVP-Encoded Small RNA-1 (HVP-EBER-1) Expression

The HVP RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) was performed using a single-stranded 30-base FITC-labeled oligonucleotide complementary (anti-sense probe) or anti-complementary (sense, negative control probe) to a portion of the HVP 1 RNA (HVP-EBER-1) gene. 30 The sequence of the anti-sense probe was 5′AGACGCTACCGTCACCTCCCGGGACTTGTA-3′. The ISH was carried out as described previously on routinely processed sections of the paraffin-embedded samples of 594S cells, and of the HVP-induced LPD lesions and their cell lines, using FITC-labeled probe and DAKO ISH detection kit for FITC-labeled DNA probe (Code No. K0607) including AP-labeled rabbit anti-FITC antibody and BCIP/NBT. 29 Cytosmears of 594S cells or immunomagnetic purified cells from PBMC or LPD (spleen or lymph nodes) of HVP-infected rabbits were also fixed in 10% conventional formalin, and HVP-EBER1-ISH was performed. Then numbers of HVP-EBER-1+ cells in each selected cell (1 × 104) by immunomagnetic purification were counted.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The 594S cells (HVP) as the positive control, B95–8 (EBV), Ts-B6 (Cyno-EBV) cells, and the spleen or peripheral blood from normal rabbits as the negative controls, and tissues and established cell lines from HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions as the samples were digested at 37°C for 2 days with proteinase K (500 mg/ml) in digestion buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 0.1% SDS). DNA was extracted by the phenol/chloroform method and ethanol precipitation. Thirty cycles of PCR were performed on 100 ng of DNA in 100 μl of PCR mixture, which consisted of 50 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.02% porcine gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 200 nmol/L dNTPs, 200 mmol/L primer pair, and 2.5 units of Taq polymerase (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). One primer pair for HVP-EBNA-1 and two primer pairs for HVP-EBNA-2 were used according to previous publications. 26,31 HPNA-1S: 5′CTGGGTTGTTGCGTTCCATG 3′, HPNA-1A: 5′TTGGGGGCGTCTCCTAACAA 3′; HPNA2–1231S: 5′ACCACTGGGACCAGTTTGGT 3′, HPNA2–1612A: 5′AGAGGACTGAGGTTCTTGC 3′; HPNA2–1485S: 5′AGCCTAGGCCCAA-TAGCTCA 3′, HPNA2–1691A: 5′CCTCCCATTGGTTGT-CAGGG 3′. Amplified PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% NuSieve gel and visualized with 0.5 mg/ml ethidium bromide.

Southern Blot Analysis

With the 594S (HVP) serving as the positive control, tissues and established cell lines from HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions as the samples, B95–8 (EBV) and Ts-B6 (Cyno-EBV) cells as comparative controls, and Ra-1 (HTLV-I-transformed rabbit T-cell line), BALL-1 and normal rabbit spleens as the negative controls, examination by Southern blotting was performed to detect the presence of the EBV or HVP genome. The details of this procedure have been described elsewhere. 32,33 Briefly, DNAs (10 μg each) were digested by the restriction enzymes, XhoI, PstI, BamHI, and/or BglII (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Rockville, MD), were subjected to electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose gel, and transferred and immobilized onto nylon membranes. Digested DNAs were hybridized with the EBV-BamHI W (3.1 kb), EBV-LMP1 (3.0 kb), EBV-XhoI (1.9 kb) fragment probes or the HVP-EcoRI“G” fragment (3.6 kb, a homologue to the Z, R, K fragment of EBV) probe labeled by a random priming procedure with fluorescein-11-dUTP at 60°C overnight, washed three times, and detected using a chemiluminescence detection kit (Gene Images random prime labeling and detection system; Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, England).

Detection of Protein and mRNA of HVP and EBV-Nuclear Antigens and Latent Membrane Protein 1 (LMP1)

An IF test was also performed for the detection of EBNA1, EBNA2, and LMP1 of human EBV. Smeared lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL, a positive control), Ra-1 (a negative control), 594S, Ts-B6, and cell line cells from HVP-induced LPD were fixed in acetone for 15 minutes at room temperature and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with mouse monoclonal antibodies against EBV-EBNA1 (OT1x, kindly donated by Dr. J. Middeldorp), EBV-EBNA2 (DAKO), and LMP1 (CS1–4, DAKO). After being washed three times with PBS, the slides were incubated with FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (DAKO) and Hoechst 33258 for 30 minutes.

RT-PCR was carried out to detect the mRNA of HVP-EBNA1, HVP-EBNA2, and HVP-LMP1. Total RNA of HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions, the positive control (594S), and the negative control (normal rabbit PBL) were extracted using the RNAqueous-Midi total RNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). RT-PCR was performed with primer pairs: HPNA-1S and 9869A: 5′CTGCCCTTCCTCACCCTCAT 3′ for HVP-EBNA1; HPNA2–1231S and HPNA2–1612A for HVP-EBNA2; PLM173S: 5′CTCACCTTAGCGCTTCTTGT 3′, and PLM362A: 5′ GCAATGAAGAGGACGAGCCA 3′ for HVP-LMP1, using mRNA selective PCR kit (Takara) containing AMV reverse transcriptase XL and AMV-optimized Taq. Amplification of β actin from each sample was performed using β-actin primers; AC3: 5′TGGAGAAAATCTGGCACCAC 3′ and AC4: 5′ GAGGCGTACAGGGATAGCAC 3′.

Clonality Analysis of HVP-Induced Rabbit LPD and Their Cell Lines

Rabbit DNA of normal liver and spleen, HVP-induced rabbit LPD in vivo, and their IL-2-dependent cell lines from HVP-induced rabbit LPD, and human DNA of a reactive lymph node case and a low-grade B-cell lymphoma case with rearrangement of both TCR Jβ2 and IgH genes were used for clonality test by Southern blotting after HindIII or BglII digestion (Bethesda Research Laboratories). Hybridized FITC-labeled probes were detected using a chemiluminescence detection kit (Gene Images random prime labeling and detection system; Amersham).

TCR Rearrangement Analysis

For rabbit TCR-β chain gene probe, we made FITC-labeled oligoprobe (oligo I): FITC-5′-ATGCAATGCCACCTTAGGGAGATG-3′ for rabbit TCR-β chain (oligo-I) according to reference paper. 34 We also used the human TCR Jβ2 probe (4.3 kb).

For rabbit TCR-γ chain probe, we made a probe for TCR-γ chain constant region according to the reference paper 35 (accession number D38134). A 242-bp DNA fragment amplified by PCR with primers of RGC6S: 5′-TATTTTTCTCCCTTCCATTGCTGA-3′ 408–431 and RGC4A: 5′-TTTCGTGTTCGACAATGCATCTGT-3′ 626–649 was subcloned using pT7Blue-T vector (Takara). Sequencing of the subcloned DNA fragment revealed 100% homology to the data-based sequence.

Rabbit IgH Gene Rearrangement

The probe was a subcloned PCR-amplified DNA fragment labeled with FITC. Seven primer pairs were synthesized according to reference data of rabbit Ig γ H-chain C-region gene (accession number L29172). A subcloned PCR-amplified DNA fragment (503 bp) was obtained by PCR with these primers and by cloning with pT7Blue-T vector and labeled with FITC, and used for the probe (RHC503). The primer pair used was RHC503-S160:5′-CATTGTACCCCTTCTCTTGC-3′ and RHC-A662:5′-AAGAAGACTGGGGTTACTGG-3′.

Tumorigenicity of Established Rabbit Lymphoid Cell Lines

The tumorigenicity of the established cell lines was examined by the subcutaneous inoculation of 1 × 107 cells into two nude mice (BALB/c AnNCrj-nu/nu, Charles River Japan Inc., Yokohama, Japan).

HVP-Infectivity of Established Rabbit Lymphoid Cell Lines in the Recipient Rabbits

HVP-infection from the established cell lines to the recipient rabbits was examined by an intravenous injection of 1 × 107 cells in one to three normal rabbits of the opposite sex from those used for establishing the cell lines.

Results

Incidence of LPD with VAHS in Rabbits Inoculated with Cell-Free Virion Pellets from 594S Cell Culture

The pathological findings for the rabbit experiments are summarized in Table 1 ▶ . Of the 16 rabbits inoculated intravenously with the cell-free virion pellets obtained from 594S culture supernatants, seven rabbits died of LPD 18 to 27 days after inoculation. LPD was also accompanied by VAHS in five of these seven rabbits. The remaining nine rabbits with LPD were killed 17 to 24 days after inoculation to be used for the primary culture or for the immunomagnetic purification of LPD lesions. No lesions were detected in the three rabbits inoculated with cell-free virion pellets from EBV-producing cells (B95–8) or HTLV-I-producing cells (Ra-1) at 90 days after the inoculation.

Antibody Responses to VCA of EBV and Laboratory Data

All of the sera from rabbits inoculated intravenously with HVP (594S) or EBV (B95–8) showed increased anti-EBV-VCA IgG antibody titers (×160 to ×2560). In contrast, the pre-experimental sera and the sera from the other control rabbits were negative (Table 1) ▶ .

Pathological Findings of Japanese White Rabbits Inoculated with HVP

Macroscopic Characteristics of the Infected Rabbits

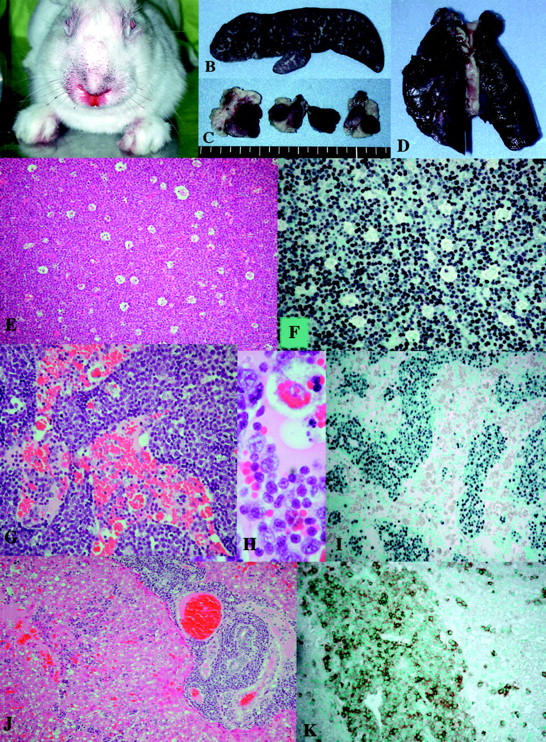

The majority of the rabbits inoculated intravenously with cell-free virion pellets from a 594S culture appeared physically healthy for 2 to 3 weeks, but showed severe rhinorrhea admixed with blood and dyspnea during the last few days before death (Figure 1A) ▶ . The autopsy of the infected rabbits revealed mild or marked splenomegaly (Figure 1B) ▶ . Dark purple swollen lymph nodes were usually observed in the neck, mediastinum, axilla, mesentery, para-stomach, hepatic hilus, or inguinal regions (Figure 1C) ▶ , usually accompanied by mild hepatomegaly. White nodules were sometimes found in the cross-section of the spleen (Figure 1B) ▶ , liver, or heart. The thymus appeared normal. Lungs showed congestion and edema, often accompanied by pulmonary hemorrhage (Figure 1D) ▶ .

Figure 1.

A: Nasal bleeding of the infected rabbit one day before its death. B: Cross-section of the enlarged spleen showing small white nodular lesions. C: Cross-section of markedly swollen dark purple lymph nodes with severe hemophagocytosis. D: Severe hemorrhage of both lungs. E and F: “Starry sky” patterns of the spleen in which the macrophages with clear cytoplasm scattered throughout a background of diffusely infiltrated atypical large lymphoid cells showing HVP-EBER1 expression (F). G–I: Atypical lymphoid cells with HVP-EBER1 expression replaced the parenchyma of the lymph node and were also observed in the sinus, accompanied with marked erythrophagocytosis (G and H). J and K: Periportal infiltration of atypical large lymphoid cells and marked central degeneration and edema of the hepatic lobule. Dominant infiltrated lymphoid cells were positive for rabbit-CD8 (K). E and J (H&E), ×75; G (H&E), ×150; H (H&E), ×750; F (EBER1-ISH), ×150; I (EBER1-ISH), ×75; K (rabbit CD8), ×150.

Microscopic Characteristics of HVP-Induced Rabbit LPD

Histological examination of rabbit tissues by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed mild to severe infiltration of atypical lymphoid cells involving many organs. Atypical large or medium-sized lymphoid cells infiltrated around perivascular areas with a diffuse or nodular pattern. Neither Hodgkin’s cells nor Reed-Sternberg’s giant cells were observed. The basic structure of the infiltrated organs was usually preserved, but was sometimes destroyed in areas of marked atypical cell infiltration. Mitotic figures were numerous and atypical cell karyorrhexis (apoptotic cells) were prominent, indicating the high growth rate and high cell turnover of these atypical lymphoid cells. “Starry sky” appearance, which is almost always observed in Burkitt’s lymphoma, was also frequently found in the HVP-induced rabbit LPD (Figure 1, E and F) ▶ . Many macrophages containing cellular debris or apoptotic bodies from individual cell necrosis were distributed among the atypical cell-infiltrated lesions, showing a “starry sky” pattern. Some of these macrophages also showed erythrophagia.

Lymph nodes, spleen, and liver were frequently and markedly involved. Most involved lymph nodes showed diffuse infiltrations of atypical lymphoid cells and marked hemophagocytosis in the sinus (Figure 1, G–I) ▶ . Expansion of interfollicular zones and replacement of secondary follicles by atypical lymphoid cell infiltration was a common feature. Nodal sinus contained atypical lymphoid cells as well as many hemophagocytes, but nodal sinus structures were usually not effaced. Severe periportal and moderate sinusoidal infiltration of atypical lymphoid cells was usually observed in the fully involved liver (Figure 1, J and K) ▶ , which was often accompanied by central degeneration of the hepatic lobules (Figure 1J) ▶ . Mild to moderate infiltration of atypical lymphoid cells was often observed in the kidneys and lungs. In some cases, focal infiltration of atypical lymphoid cells was found in the heart, thymus, or bone marrow. Atypical lymphoid cells also invaded the gastrointestinal tract, adrenal glands, tongue, salivary gland, fat tissues, and muscle. Atypical lymphocytes were often found in the blood vessels. Hemophagocytosis was also found in the spleen and thymus.

On sequential examination of HVP-infected rabbits without a bleeding tendency before full development of LPD and hemophagocytosis, LPD lesions detected on day 17 when it was the first check, were mild and focal in the normal-sized spleen, and later LPD involvement of the liver or lymph nodes was disclosed. Development of LPD occurred chiefly during about last one week before death, while the rabbits inoculated intravenously with HVP usually died during weeks 3 to 4. Bleeding tendency and hemophagocytosis also appeared in the terminal stage.

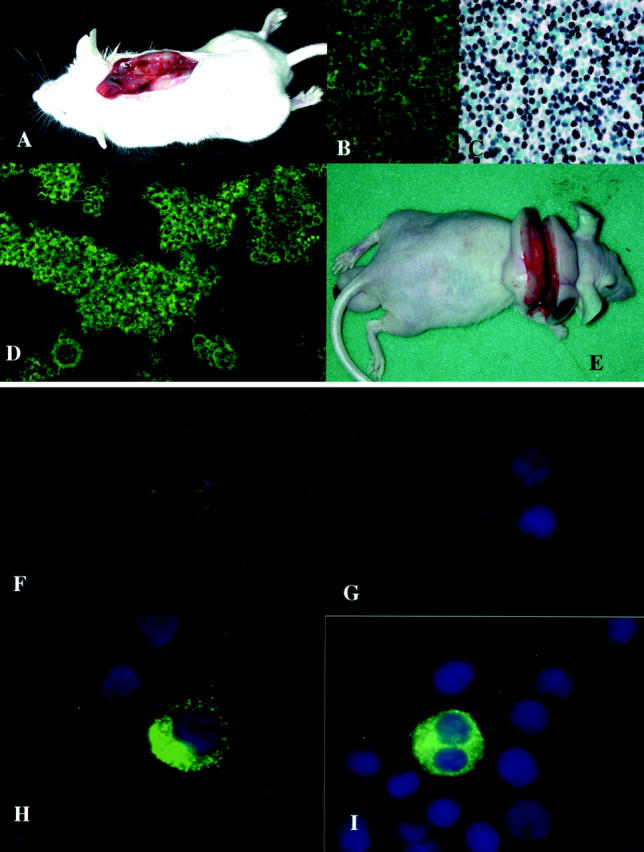

Establishment of Tumor Cell Lines and Chromosomal Analysis

Six IL-2-dependent rabbit lymphoid cell lines (Table 2) ▶ could be established from the transplanted scid tumors (Figure 2A) ▶ from 3 of 5 HVP-induced cases of rabbit LPD (Table 1) ▶ . Each cell line had lymphoid morphology and grew steadily only in the medium supplemented with IL-2 (doubling time, 3 to 7 days) in suspension culture as aggregates or as single cells (Figure 2D) ▶ . However, all repeated trials to establish a cell line from the rabbit LPD or from transplanted scid tumors of rabbit LPD using conventional primary culture without IL-2, failed.

Table 2.

Characterization of IL-2-Dependent Rabbit Lymphoid Cell Lines Derived from HVP-Induced Rabbit LPD Lesions

| Rabbit cell lines | ISH EBER1* | PCR EBNA1/2 | Southern EBNA1 | Immunohistochemistry (flow cytometry) | IF EBNA2 | IF LMP1 | RT-PCR | Chromosome | Nude tumor | Rabbit LPD† | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT1 | RT2 | CD5 | CD4 | CD8 | CD45a | CD11b | CD25 | CD79a | RABELA | EBNA2 | LMP1 | |||||||||

| J10Sp-scidT line | + | + | + | + | + | +, + | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | + | normal: 44,xx | 0/2 | 2/2 |

| J10LN-scidT-II line | + | + | + | + | + | +− | − | +− | +++ | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | normal: 44,xx | 0/2 | 2/2 |

| J11Sp-scid1T line | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | − | − | + | − | + | 44,xx,−17,+mar | 0/2 | 1/1 |

| J11LN-scidT line | + | + | + | +− | +− | − | − | − | +++ | − | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | normal: 44,xx | 2/2 (1/2)‡ | 0/1 |

| J13Sp-scid-livT line | + | + | +,− | +− | +− | ++ | − | +− | ++ | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | normal: 44,xx | 2/2 | 0/1 |

| J13LN-scid2T line | + | + | + | − | − | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | + | normal: 44,xx | 2/2§ | 2/3 |

| J13LN-scid2T-II-nudeT line¶ | −/+ | + | − | −/+ | − | + | − | − | +++ | − | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | + | 43,x,−x,−12, +mar/44,xx/44, xx,−12,+mar/45, XX,+5,−12,+mar | NE | NE |

EBER1*, HVP-EBER1;

¶, this cell line is IL-2 independent;

†, rabbit LPD induced by intravenous inoculation of the established cell lines; IF, immunofluorescence test; RABELA, rabbit bursal equivalent to lymphocyte antisera;

‡, one of two transplanted nude tumors was regressed;

§, transplanted nude tumors growed rapidly; NE, not examined.

Figure 2.

A: Transplanted tumor of HVP-induced rabbit LPD in a scid mouse. B: The immunofluorescence (IF) study revealed rabbit CD8 expression of the transplanted tumor cells. C: The transplanted tumor cells expressed HVP-EBER1. D: Phase contrast of an IL-2-dependent rabbit lymphoid cell line established from the transplanted tumor of a scid mouse. E: The transplanted nude mouse tumor of an IL-2-dependent rabbit cell line. F–I: The IF study revealed EBNA2 expression in the nucleus of the positive control (F, 594S), but not in the rabbit cell line (G). LMP-1 expression was detected in the positive control (H, LCL) and in a rabbit cell line (I). The nuclei of the cells in F through I were counterstained with Hoechst 33258.

Chromosomal analysis of all rabbit LPD lesions in both spleen and lymph node of five HVP-infected rabbits revealed the normal rabbit karyotype (44, XX). Five of six IL-2-dependent lymphoid cell lines from HVP-induced cases of rabbit LPD also had the normal rabbit karyotype (Table 2) ▶ . Only the J11Sp-scidT line showed mild chromosomal abnormalities (44, XX, −17, +mar). In addition, an IL-2-independent cell line (J13LN-scid2T-II-nudeT line) was obtained from a transplanted nude mouse tumor of an IL-2-dependent cell line (J13LN-scid2T line). This had complex chromosomal abnormalities (43, X, −X, −12, +mar/44, XX/44, XX, −12, +mar/45, XX, +5, −12, +mar).

Immunophenotypes of the HVP-Induced Rabbit LPD and Their Cell Lines

The immunohistochemical analyses using frozen tissues revealed that dominant atypical lymphoid cells were frequently positive for rabbit CD45, CD5, MHC class II DQ, CD25, and also for rabbit CD4 or CD8 (Figure 1K) ▶ . Rabbit CD79a-positive cells were also observed as a small component of infiltrated lymphoid cells. These atypical lymphoid cells showed no expression of rabbit RABELA (rabbit B-cell marker). Dominant lymphoid cells that infiltrated in the liver were T cells (CD-8), while both T and B cells were detected in the spleen and lymph nodes examined. Some of the transplanted scid tumors expressed rabbit-CD8 (Figure 2B) ▶ .

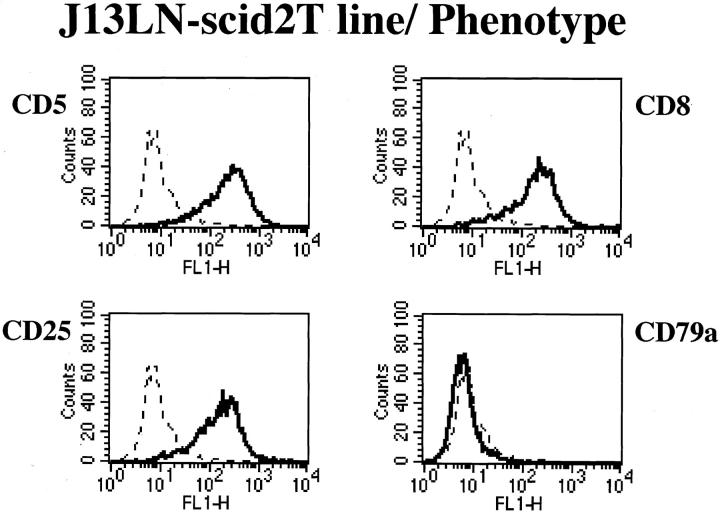

Flow cytometry analysis of the cell lines from HVP-induced rabbit LPD is summarized in Table 2 ▶ . These cell lines have T-cell phenotypes and IL-2 receptors (CD25). Four cell lines are positive for rabbit CD8 (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Representative flow cytometry analysis data on phenotype of rabbit cell lines. J13LN-scid2T line showed T-cell markers (CD5 and CD8) and an IL-2 receptor marker (CD25), but not a B-cell marker (CD79a).

Detection of the EBV-Like Genome

HVP-EBER-1 Expression

The HVP-EBER-1-ISH revealed that most of the 594S cells expressed EBER-1. In all 17 cases (100%) of LPD, HVP-EBER-1 expression was detected in virtually all atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 1, F and I) ▶ . The HVP-EBER-1 signal was mostly nuclear. Rare and scattered small non-atypical lymphocytes with HVP-EBER-1 expression were also identified in some rabbits with LPD.

Numbers of HVP-EBER-1+ cells in cells selected by immunomagnetic purification are summarized in Table 3 ▶ . HVP-EBER-1+ cells were observed in all selected fractions of CD4 (+), CD4 (−), CD8 (+), CD8 (−), CD79a (+), or CD79a (−) cells from the spleen, lymph node, or PBL of HVP-infected rabbits.

Table 3.

HVP-EBER1+ Cell Population in Magnetic Cell-Sorted Cells from Sacrificed HVP-Infected Rabbits at the Consecutive Dates

| Sacrificed date after HVP inoculation and rabbit name | 17th day, J32 rabbit | 18th day, J30 rabbit | 19th day, J29 rabbit | 20th day, J31 rabbit | 21st day, J23 rabbit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Splenomegaly | − | − | Moderate | Very mild | Marked | |||||

| EBER1+ cells in spleen tissues | <0,01% | 10–30% | >50% | 10–20% | >90% | |||||

| EBER1+ cells in LN tissues | 0% | <1% | <5% | <0,1% | >50% | |||||

| Samples for MACS | J32-Sp (17d) | J32-PBL (17d) | J30-SP (18d) | J30-PBL (18d) | J29-Sp (19d) | J29-LN (19d) | J31-Sp (20d) | J31-LN (20d) | J23-Sp (21d) | J23-LN (21d) |

| EBER1+ cells /1×104 CD4(+) | − | − | +, 10 | − | +, 451 | − | +, 20 | − | +, 8579 | +, 6845 |

| EBER1+ cells /1×104 CD4(−) | +, 30 | +, 1 | +, 450 | +, 2 | +, 5521 | +, 357 | +, 242 | +, 8 | +, 1845 | +, 4487 |

| EBER1+ cells /1×104 CD8(+) | +, 5 | +, 1 | +, 100 | − | +, 1243 | +, 178 | +, 186 | +, 1 | +, 2578 | +, 1510 |

| EBER1+ cells /1×104 CD8(−) | +, 8 | − | +, 540 | +, 2 | +, 4352 | +, 755 | +, 203 | +, 4 | +, 4875 | +, 1987 |

| EBER1+ cells /1×104 CD79a(+) | +, 11 | − | +, 15 | +, 1 | +, 2386 | +, 3764 | +, 115 | +, 1 | +, 12 | +, 178 |

| EBER1+ cells /1×104 CD79a(−) | +, 21 | − | +, 400 | +, 12 | +, 2784 | +, 132 | +, 50 | +, 1 | +, 4726 | +, 5826 |

HVP-EBER1, HVP-associated small RNA 1; MACS, magnetic cell sorting; Sp, spleen; LN, lymph node; PBL, peripheral blood leukocytes.

All transplanted scid tumors examined showed HVP-EBER-1 expression (Figure 2C) ▶ , and all IL-2-dependent rabbit lymphoid cell lines from transplanted scid tumors also expressed HVP-EBER1. However, dominant cells in the IL-2-independent cell line from a transplanted nude tumor (J13LN-scid2T-II-nudeT line) were negative for HVP-EBER-1.

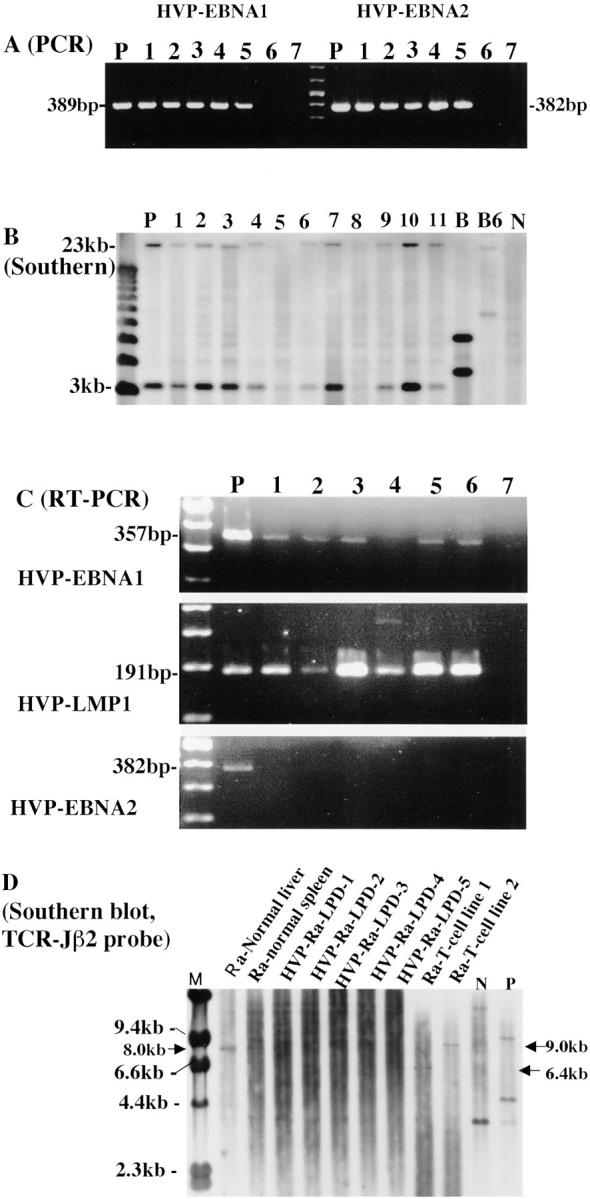

PCR

PCR using one primer pair for the HVP-EBNA-1 region (HPNA-1S and HPNA-1A) revealed amplified DNA at the position of 389 bp in the positive control (594S) and rabbit lymphoid cell lines (Figure 4A) ▶ . The PCR using two primer pairs for the HVP-EBNA-2 region (HPNA2–1231S and HPNA2–1612A: HPNA2–1485S and HPNA2–1691A) showed DNA amplification at the position of 382 bp or 207 bp, respectively, in the positive control (594S) and rabbit lymphoid cell lines from HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions (Figure 4A) ▶ . However, no amplification by PCR was seen in the negative controls [Ts-B6 (Cyno-EBV) or B95–8 (human EBV)].

Figure 4.

A: PCR for HVP-EBNA1 and HVP-EBNA2 in rabbit lymphoid cell lines from HVP-induced LPD of rabbits. HVP-EBNA1 and HVP-EBNA2 DNA were amplified at the positions of 389 and 382 bp, respectively, in the positive control [lane P, 594S (HVP)] and rabbit lymphoid cell lines (lanes 1 through 5: 1, J10Sp-scidT line; 2, J11Sp-scidT line; 3, J13LN-scid2T line; 4, J11LN-scidT line; 5, J10LN-scidT line, respectively), but not in the negative controls [lane 6, B95–8 (human EBV), lane 7, Ts-B6 (Cyno-EBV)]. B: Southern blot analysis for the presence of HVP-DNA in rabbit lymphoid cell lines. Sample DNAs were digested by BamHI, and hybridized with the HVP-EcoRI“G” fragment probe that includes the EBNA-1 region. Two positive bands (3.4 kb and 23 kb) were detected in the positive control (lane P, 594S) and in most of the rabbit lymphoid cell lines (lanes 1 through 8 except two lanes 5 and 8: 1, J10Sp-scidT line; 2, J10LN-scidT-II line; 3, J11Sp-scid1T line; 4, J11LN-scidT line; 6 and 7, J13LN-scid2T line, respectively), and HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions (lanes 9 through 11). B95–8 (human EBV, lane B) and Ts-B6 (Cyno-EBV, lane B6) showed two different-sized positive bands. No positive band was detected in two rabbit cell lines (lane 5, J13Sp-scid-livT line; lane 8, J13LN-scid2T-11-nude T line) or in the negative control (lane N, Ra-1). C: RT-PCR revealed expression of both HVP-EBNA1 mRNA and HVP-LMP1 mRNA at the position of 357 bp and 191 bp, respectively, in the positive control (lane P, 594S) and in rabbit lymphoid cell lines (lanes 1 through 6: J10Sp-scidT line, J10LN-scidT-II line, J11Sp-scid1T line, J11LN-scidT line, J13Sp-scid-livT line and J13LN-scid2T line, respectively), but not in the negative control (lane 7). No transcript of HVP-EBNA2 was detected in any of the rabbit cell lines or in the negative control. The transcript was seen only in the positive control (lane P). D: Clonality analysis by Southern blotting in HVP-induced rabbit LPD. Sample DNA was digested by BglII, and hybridized with TCR-Jβ2 probe. TCR-Jβ2 gene rearrangement was detected at the position of 6.4 kb or 9.0 kb in rabbit T-cell lines with HVP infection and at different positions in human positive control (P), while germline (at the position of 8.0 kb) or polyclonal bands of TCR-Jβ2 gene were observed in normal rabbit liver, spleen, or 5 HVP-induced rabbit LPDs and at different position in human reactive lymphoid tissues (N).

Southern Blot Analysis

Southern blot analysis was carried out using HVP-EcoRI “G fragment” probe after digestion of sample DNA with BamHI. This revealed the presence of HVP DNA at the positions of 3.4 kb and 23 kb in the positive control (594S). HVP DNA was also found in most rabbit lymphoid cell lines established from HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions (J10Sp-scidT line, J10LN-scidT-II line, J11Sp-scid1T line, J11LN-scidT line, J13LN-scid2T line) and HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions, but not in two rabbit cell lines (J13Sp-scid-livT line, J13LN-scid2T-II-nudeT line) or in the negative control (Ra-1) (Figure 4B) ▶ . Two positive bands at different-sized positions were detected in B95–8 and Ts-B6 (Cyno-EBV) (Figure 4B) ▶ . The Southern blot analysis with the EBV-BamHI W probe, EBV-LMP1 probe, or EBV-XhoI 1.9-kb fragment showed positive bands only in B95–8 or Ts-B6, but no positive band was detected in 594S and HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions.

Latency Type of HVP-Infection in Rabbit Lymphoid Cell Lines from HVP-Induced Rabbit LPD

Detection of EBNAs and EBV-LMP1

The IF study using anti-human EBV monoclonal antibodies revealed EBNA-1, EBNA-2, and LMP1 expression in the positive control cells (LCL, Figure 2H ▶ ) and B95–8. Cross-reactive expression of EBNA-2 was observed in a few 594S cells (Figure 2F) ▶ , but no cross-reactivity of EBNA-1 or LMP1 was detected in the 594S cells. No expression of EBNA1 or EBNA2 was detected in all rabbit cell lines (Figure 2G) ▶ . A few cells of only one rabbit cell line (J11Sp-scidT line) showed LMP1 expression (Figure 2I) ▶ .

Detection of mRNA of HVP-EBNAs and HVP-LMP1

The mRNAs of HVP-EBNA1 and HVP-LMP1 were detected by RT-PCR in 594S cells and established rabbit cell lines at the position of 357 bp and 191 bp, respectively, but not in the negative control (Figure 4C) ▶ . No HVP-EBNA2 transcript was detected in rabbit cell line samples examined (Figure 4C) ▶ . β-actin was amplified at the position of 190 bp in all samples.

Clonality of HVP-Induced Rabbit LPD and Their Cell Lines

Rabbit TCR Gene Rearrangement

Germinal band or polyclonal bands of TCR-Jβ2 gene were detected in normal rabbit liver, spleen, all HVP-induced rabbit LPDs and human reactive lymphoid tissues (N), while rearrangement band was shown in HVP-infected rabbit T-cell lines and human positive control (Figure 4D) ▶ . No data were obtained by Southern blotting using Oligo-I probe. Southern blot analysis with HindIII or BglII digestion and FITC-labeled TCR γ chain probe showed germline bands in both rabbit and human DNA materials.

Rabbit Ig γ H-Chain Gene Rearrangement

Southern blot analysis with HindIII or BglII digestion and FITC-labeled Ig γ H-chain probe showed germline in rabbit DNA and human reactive lymphoid tissue (N) except human positive control with Ig γ H-chain gene rearrangement.

Tumorigenicity of Established Rabbit Lymphoid Cell Lines

The tumorigenicity results are summarized in Table 2 ▶ . Three of six IL-2-dependent rabbit lymphoid cell lines showed tumorigenicity in nude mice (Figure 2E) ▶ .

HVP-Infectivity of Established Rabbit Lymphoid Cell Lines in the Recipient Rabbits

Four of six IL-2-dependent rabbit lymphoid cell lines induced seroconversion against EBV-VCA and subsequent LPD and death of the inoculated rabbits.

Discussion

We previously reported that the high rate of fatal LPD with HPS induction in New Zealand White rabbits is caused by intravenous or peroral inoculation of HVP, and this was the first animal in vivo model for EBV-AHS, which is useful for studying the pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of human EBV-AHS. 29 This rabbit model of fatal LPD with VAHS induced by primary infection of HVP 29 showed clinicopathologic features similar to childhood EBV-AHS, 10,11 a fulminant EBV-positive T-cell LPD and hemophagocytosis after acute/chronic EBV infection, 36 in that: the rabbits used were previously healthy and had no immunodeficiency background; the affected rabbits showed seroconversion and a fulminant course and high mortality after anywhere from 3 weeks to 3 months; hepatosplenomegaly with liver injury or necrosis, systemic lymph node swelling, and a bleeding tendency were frequently observed; a typical lymphoid cell infiltration was detected in many organs, particularly the lymph nodes, spleen and liver; fatal rabbit LPD with HPS was induced by oligoclonal atypical T-cell proliferation; hemophagocytosis was also present markedly in the lymph nodes, moderately in spleen, and mildly in bone marrow; and this rabbit system can also be developed by oral spray of HVP, 29 indicating that infection occurs by the same natural transmission route as does human EBV.

In the present study, atypical lymphocytes in the HVP-induced LPD of Japanese White rabbits expressed HVP-EBER1 and were found by PCR or Southern blot analysis to contain HVP-DNA, but not human EBV nor cynomolgus EBV. In toto, the data described above indicate that the LPD and VAHS of Japanese White rabbits were also induced by HVP, but not by human EBV or other well-known simian oncogenic viruses such as cynomolgus EBV. In this study, we focused especially on elucidating the true nature of HVP-induced rabbit LPD. We obtained many important new findings that were not disclosed in the previous report, 29 such as: HVP-induced rabbit LPD is initially developed in the spleen about one week before death. LPD advances rapidly to generalized fatal LPD with HPS, as observed during the sequential autopsy analysis; sequential analysis of HVP-EBER1+ cell populations using immunomagnetically purified cells from LPD lesions revealed that not only HVP-infected T cells (CD4+ or CD8+), but also HVP-infected B cells (CD79a+), proliferated in the PBL and LPD lesions from spleen or lymph nodes before death; the dominant lymphoid cells that infiltrated in LPD of the liver were T cells (CD8), while both T cells and B cells were observed in the spleen and lymph nodes; clonality analysis of HVP-induced LPD showed polyclonal bands by Southern blotting; six IL-2-dependent rabbit lymphoid cell lines were established from the transplanted scid tumors of LPD in three of five HVP-infected rabbits, whereas no cell line was obtained without using IL-2 from the HVP-induced LPD of 10 rabbits. This included five rabbits examined for the previous report; normal rabbit karyotype was detected in five of six IL-2-dependent cell lines and in all primary LPD lesions in the spleens and lymph nodes of five HVP-infected rabbits that were used for primary culture; these IL-2-dependent rabbit cell lines with HVP infection have a T-cell phenotype (CD8) and three of six cell lines showed tumorigenicity in nude mice; these rabbit T-cell lines showed latency type I/II (EBNA1+, LMP1− or +) of HVP-infection, while latency type III (EBNA1+, LMP1+, EBNA2+) was observed in HVP-induced rabbit LPD in vivo in the previous study; 29 the newly developed HVP-EBER1-ISH system is the best way to identify HVP-infected cells, and is superior to the EBV-EBER1-ISH used in the previous study; 29 and the Japanese White rabbits used in this HVP infection study also showed similar clinicopathological features to those of HVP-infected New Zealand White rabbits used in the previous report. 29 The proliferating lymphoid cells in the acute HVP-infected rabbit model for EBV-AHS in this study are reactive polyclonal HVP-infected cells, and the rabbits with HVP infection usually died within 3 to 4 weeks of VAHS, which typically involved bleeding, especially terminal hemorrhage of the lungs and liver damage. HVP-infected rabbits also died of fulminant polyclonal LPD before the development of completely monoclonal neoplastic lymphoma with clonal cytogenetic abnormalities. However, it is possible that these rabbit LPD lesions may contain some small components of polyclonal T cells with HVP infection, which can progress to neoplastic cells with tumorigenicity by selections occurring through transplantation and culture using IL-2. Probably HVP-infected rabbit T cells with latency type I/II can escape and be saved from attacks of host immunity, but rabbit cells with latency type III were eliminated by the immunity of rabbits or transplanted mice. B-cell clones might be completely reactive and have no tumorigenicity even in scid mice. These are the reasons why only T-cell lymphoma or LPD were induced in rabbits inoculated with simian EBV-like viruses in previous reports. 29,32,33 If we could develop a chronic active HVP infection model of rabbits, then this might show that HVP-infected rabbit T cells would progress to the true T-cell lymphoma in vivo during the long infectious course.

Another interesting point is that HVP-DNA was either not detected or was barely detected by Southern blotting in the following two rabbit cell lines with tumorigenicity (Figure 4B) ▶ : the J13Sp-scid-livT line was established from liver metastatic foci of transplanted scid LPD tumors; and the J13LN-scid2T-II-nudeT line, which is IL-2-independent, was established from transplanted nude tumors of the IL-2-dependent J13LN-scid2T line. These results suggest that higher tumorigenic cell lines show a tendency to be chiefly composed of the HVP-negative cells.

Chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV) is a syndrome that takes diverse clinical courses and is often associated with LPD of T/natural killer (NK)-cell lineage. Two Japanese patients diagnosed with severe CAEBV subsequently developed EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma with monoclonal EBV infection and type II EBV latency gene expression. 37 Nagata et al 38,39 also described a patient with CAEBV and with subsequent nasal T/NK-cell lymphoma. By means of high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 administration, they established an EBV-positive cell line of NK-cell lineage from expanded three NK-cell clones. This line was involved in the formation of the lymphoma. These results suggest that the proliferative capacity of EBV-positive cells can be variable even in a single patient, and this variability may explain the clinical diversity in CAEBV. On the other hand, proliferative lymphoid cells in an acute rabbit model with HVP-induced fatal LPD and VAHS contain biologically variable cells, which are at least CD4+, CD8+, or CD79a+. The proliferative capacities of HVP-induced rabbit LPD cells and IL-2-dependent rabbit T-cell lines were variable with respect to transplanted tumorigenicity in scid or nude mice (Tables 1 and 2) ▶ . The presence of various HVP-infected rabbit cell clones with different proliferative capacities in the HVP-induced rabbit LPD, some of which can progress to neoplastic lymphoid cells during culture, is similar to those pathological conditions of CAEBV. The normal rabbit karyotype of HVP-induced LPD lesions in vivo as detected by chromosomal analysis does not necessarily imply that all LPD cells had a completely normal nature. Furthermore, it is possible that some HVP-infected cells with abnormalities may be present among HVP-induced rabbit LPD.

The latency type of EBV has not yet been identified in fatal EBV-AHS that occurs in childhood, but recently Yoshioka et al 40 demonstrated EBV latency type III infection in three patients with EBV-AHS, using RT-PCR with PBMC and spleen. Based on the latency type of human EBV, latency type of HVP infection can be defined as follows: latency type I; HVP-EBNA1 (+), HVP-EBNA2 (−), HVP-LMP1 (−): latency type II; HVP-EBNA1 (+), HVP-EBNA2 (−), HVP-LMP1 (+): latency type III; HVP-EBNA1 (+), HVP-EBNA2 (+), HVP-LMP1 (+). The latency type of HVP-infection-associated rabbit fatal LPD and of VAHS in vivo was also type III, because all transcripts of HVP-EBNA1, HVP-EBNA2, and HVP-LMP1 have been detected in the rabbit lesions examined. 29 However, the detection of type III latency by RT-PCR in HVP-induced rabbit LPD lesions does not necessarily mean that all HVP-infected cells have latency type III. In other words, it is possible that rabbit LPD lesions may contain not only type III but also type I or type II latency cells. In fact, rabbit T-cell lines established from HVP-induced rabbit LPD showed latency type I/II HVP infection in this study. This latency of type I/II is consistent with that observed in the two Japanese cases of T-cell lymphomas following chronic/active EBV infection. 37

Antibodies used in this study for rabbit CD antigens cannot be applied to paraffin-embedded materials, and we could not employ the double-staining of HVP-EBER1-ISH and immunohistochemistry for identifying the precise phenotype of HVP-infected rabbit cells. Therefore, an immunomagnetic cell sorting method was used for purifying selected cells such as rabbit-CD4+, -CD8+ or -CD79a+ cells. Then HVP-EBER1-ISH was performed on immunomagnetically purified cells. Consequently, HVP-infected cells were included in all purified cell fractions of CD4+, CD4−, CD8+, CD8−, CD79a+, or CD79a−.

CD8+ cells are particularly important for eliminating the viral-infected cells. Callan et al 41 showed that large monoclonal or oligoclonal populations of CD8+ T cells account for a significant proportion of the lymphocytosis in acute infectious mononucleosis. The selective and massive expansion of a few dominant clones of CD8+ T cells has been driven by antigens of EBV and this is an important feature of the primary response to EBV. In our HVP-infected rabbit model, rabbit CD8+ clones are a major source of the established rabbit cell lines from HVP-induced LPD and VAHS.

The newly developed HVP-EBER1-ISH system is superior to the EBV-EBER1-ISH used in the previous study, 29 because probes for HVP-EBER1-ISH were synthesized according to the sequence of the HVP-EBER1 region. HVP-EBER1 is a homologue of EBV-EBER1 and has significant similarity in both sequence and predicted secondary structure of EBV-EBER1. 30 EBV-EBER-1 expression was detected in virtually all atypical lymphoid cells in the previous study. 29 However, the intensity of EBV-EBER-1 expression varied among lymphoid cells of the different tissues or organs, and pseudo-negative expression of EBV-EBER1 was experienced in some samples. Therefore, repeated trials of ISH were sometimes needed. The newly developed HVP-EBER1-ISH enables us to detect the precise distribution of HVP-infected cells with strong and clear HVP-EBER1 expression. For example, this new ISH revealed many HVP-infected lymphoid cells in the lymph node sinuses or vessels, where few EBV-EBER1-positive cells were detected by the previous EBV-EBER1 ISH. 29

HVP-induced LPD with VAHS in Japanese White rabbits used in this study is essentially the same as those in New Zealand White rabbits used in the previous report. 29 However, the “starry sky” pattern in HVP-induced LPD was more frequently and prominently observed in Japanese White rabbits, reminding us of the histological character of Burkitt’s lymphoma.

Clonality analysis of HVP-induced rabbit LPD by Southern blotting with TCR gene probe revealed the polyclonal bands and these data generally suggest that HVP-induced rabbit LPD are not monoclonal neoplasm, but reactive and polyclonal in nature of T cells.

Cell line establishment from HVP-induced rabbit LPD was impossible by the routine primary culture methods, but was made possible through transplantation to scid mice and supplementation of high dose IL-2 (500 IU/ml) in the culture medium. Three of six IL-2-dependent rabbit lymphoid cell lines with HVP-infection are tumorigenic in nude mice. These results suggest that HVP-induced LPD is almost non-neoplastic and reactive in nature, but may contain some small potions of HVP-infected cells, which can progress to neoplastic cells with tumorigenicity by selections occurring through transplantation and culture using IL-2. In addition, four of six cell lines can induce HVP infection with seroconversion and subsequent fatal LPD and hemophagocytosis in inoculated rabbits after about 3 months. This implies that some fractions of the IL-2-dependent lines inoculated in rabbits come to produce HVP, although these cell lines maintain latency type I/II infection in vitro. On the other hand, cell lines were easily established without transplantation or IL-2 supplementation from cynomolgus-EBV-induced rabbit T-cell lymphomas. 33,42,43 Five of six cell lines showed tumorigenicity in nude mice. The cell lines inoculated in rabbits did not induce seroconversion in the inoculated rabbits. 33

The reasons for the high susceptibility of rabbits to LPD with VAHS by HVP remain to be elucidated. If the pathogenic mechanism of human VAHS were the same as that of this rabbit model, we can speculate that HVP-infected proliferating T cells secrete a non-regulated excess of cytokines, which activate macrophages and induce a storm of cytokine production from macrophages, resulting in VAHS. The HVP-infected cells with immunogenic virus-related antigens recognized by cytotoxic T cells may be excluded, and the T cells with latency type I/II infection can thus escape from host immunity and take advantage of proliferation, subsequently progressing to become neoplastic clones. Alternatively, disorders of cytotoxic T-cell response may be caused by HVP-infection of rabbit CD8 cells themselves. Further studies, including in vitro transformation experiments of rabbit lymphocytes, are needed to address these problems.

We have tabulated a comparative overview analysis, presented in Table 4 ▶ , of EBV-associated diseases in humans, 2,44 simian EBV-associated lymphoma in rabbits, 32,33,42,43,45,46 and HVP-induced rabbit LPD with VAHS. 29

Table 4.

Comparative Overview of EBV-Associated Diseases (Tumors) in Humans* and Their Compatible Animal Models

| EBV-associated tumor | Proposed cell of origin | Typical latent period | EBV gene expression | Latency type | Animal model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious mononucleosis (IM) | B cell | 5 weeks | EBNA1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C,−LP, LMP1, LMP2+ | III (lytic) | + (monkey, mice) |

| Burkitt’s ML | Centroblast | 3–8 years | EBNA1+ | I | − |

| PTLD-like lymphoma (B-lymphoproliferative disease) | B cell, immunoblast | <3 mo, immunodeficiency; <1 year, post-transplant; 8 years, post-HIV | EBNA1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C,−LP, LMP1, LMP2+ | III (with lytic cells) | + (monkey, mice, scid mice) |

| Pyothorax-associated lymphoma | B cell | 33 years post-treatment | EBNA2+, LMP1+ | III | − |

| Hodgkin’s disease | Follicle center B cell, immunoblast | >10 years | EBNA1+, LMP1+, LMP2+ | II | − |

| VAHS/fatal IM (T-cell ML) | T cell | <6 months | EBNA1+, (LMP1+), LMP2+ | III (I/II) | + (rabbit) |

| T-cell ML | T cell | >30 years | EBNA1+, (LMP1+), LMP2+ | I/II | + (rabbit) |

| Nasal T/NK cell ML | T/NK cell | >30 years | EBNA1+, (LMP1+), LMP2+ | I/II | − |

| Gastric carcinoma | Glandular epithelia | >30 years | EBNA1+, LMP2+ | I/II | − |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Squamous epithelia | >30 years | EBNA1+, (LMP1+), LMP2+ | I/II | − |

| Leiomyosarcoma | Smooth muscle | ?<3 years | ? | ? | − |

*This table was modified from the tables in the textbook (Rickinson AB, Kieff E; Epstein-Barr virus in Fields Virology 1996, 2001).

ML, malignant lymphoma; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease; VAHS, virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome; AILD, angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy-like; IM, infectious mononucleosis.

Despite many investigations into the role of EBV infection in the pathogenesis of human EBV-associated tumors, a direct causal relationship between EBV infection and these tumors has been established only for the opportunistic malignant lymphomas arising with a relatively short latency period in immunocompromised individuals. On the other hand, most EBV-associated tumors arise with a very long latency in long-term EBV carriers (Table 4) ▶ . This suggests multi-step oncogenesis through malignant transformation from a single cell within the EBV-infected pool. 2 It is generally accepted that risk factors such as genetic background, ethnicity, environmental factors including nitrosamines in foods, economic status, and malarial or Helicobacter pylori infection, and the mutation or deletion of genes like p53, are needed for the development of other EBV-associated tumors in addition to EBV infection. However, there are different hypotheses stating that EBV is only an innocent bystander virus, or that EBV just infects the tumor cells after the malignant transformation of EBV-non-infected cells, and EBV does not contribute to the oncogenic process. 47,48 EBV-DNA is usually present in the nuclei of the infected cells as a plasmid, and is only rarely integrated into the DNA of the infected cells. 49 This also makes it difficult to explain the pathogenesis of EBV in EBV-related tumors.

However, EBV contributes to the malignant phenotype, such as growth in low serum concentration, anchorage-independent growth in soft agar, and tumorigenicity in nude mice. 50 Oncogenic roles of EBERs and resistance to apoptosis by EBERs are also demonstrated in a Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) cell line Akata. 51,52

Simian EBV-like virus-induced rabbit models of EBV-related LPD 29,32,33,53,54 are also summarized in Table 5 ▶ . We have previously reported an animal model of EBV-associated lymphomagenesis in humans: the malignant T-cell lymphoma induction of rabbits by EBV-like viruses from cynomolgus monkeys. 32,33,42,43,45,46 It was shown that malignant lymphomas (MLs) frequently develop in approximately 80 to 90% of rabbits after a short latency period (about 2 to 5 months) following intravenous injection or peroral spray of cynomolgus EBVs (Si-IIA-EBV, Cyno-EBV). This rabbit model was initially established by chance via studies of the HTLV-II-infected cynomolgus cell line (Si-IIA). 42,43,55 The direct causative relationship between infection by EBV-like viruses (cynomolgus-EBVs, 32,33 HVMA, 53 and HVMNE 54 ) and the subsequent development of ML is very clear in the EBV-like virus-infected rabbit experimental models, reinforcing the assertion that EBV plays a significant role in the development of EBV-associated tumors. According to the comparative overview data of EBV-associated diseases in human and rabbits (Tables 4 and 5) ▶ , these rabbit lymphomas induced by simian EBV-like viruses are very good models for the fatal T-cell LPD seen in fatal infectious mononucleosis/fatal LPD with EBV-AHS or EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma. In the broad sense, these are also good models for the human EBV-associated T-cell lymphomas, and they can be instrumental in defining EBV genes involved in T-cell LPD or lymphoma. However, acute or subacute models of HVP-induced rabbit fatal LPD with VAHS are similar to fulminant EBV-AHS or CAEBV, rather than to EBV-associated T-cell lymphomas arising with a long latency. In Table 4 ▶ , it is noteworthy that there have been no animal in vivo models for EBV-infected epithelial tumors such as a setting of nasopharyngeal carcinoma or gastric carcinoma. To elucidate details of the pathogenesis of EBV-associated diseases and to develop appropriate therapeutic trials using animal models, sequential follow-up studies, and clarifying functions of the oncogenes of EBV or EBV-like viruses are needed. Sequential examinations of copy numbers of virus by quantitative PCR 56,57 and population changes of some virus-infected cells collected by cell sorting technique are necessary, using blood or tissue samples from experimental animals. The identity of the most important oncogenic gene of the EBV-like virus must also be established.

Table 5.

Rabbit Models of EBV-Related Lymphoproliferative Diseases (LPD) by Simian EBV-Like Virus

| Author (year) | Simian EBV | Type of LPD | Typical latent period | Frequency of LPD by intravenous inoculation | Peroral infection | EBV gene expression | Latency type | Similar disease of humans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayashi (1995, 1999) | Cyno-EBV, Si-IIA-EBV (HVMF1) | Rabbit ML (T cell) | 2–5 months | 90%* (77%**) | 85% | EBNA1+, EBNA2−, LMP1−? | I (II) | EBV-associated ML (T-cell) |

| Wutzler (1995) | Herpesvirus from Macaca arctoides | Rabbit ML (?) | 21–143 days | 41%*** | ? | ? | ? | EBV-associated ML (?) |

| Ferrari (2001) | Herpesvirus from Macaca nemestrina | Rabbit ML (T cell) | 3–9 months | 70%* (20%**) | ? | ? | ? | EBV-associated ML (T-cell) |

| Hayashi (2001) | Boboon-EBV [Herpesvirus papio (HVP)] | NW Rabbit fatal LPD with VAHS (T cell) | 3 weeks–3 months | 85%* (100%**) | 60% | transcripts+ of HVP-EBNA1, EBNA2 & LMP1 | III (in vivo) | EBV-associated fatal LPD with VAHS (T cell ML) |

| Hayashi (present study) | Boboon-EBV [Herpesvirus papio (HVP)] | JW Rabbit fatal LPD with VAHS (B & T cell) | 3–4 weeks | Not done* (100%**) | Not done | HVP-EBNA1 transcript+, HVP-LMP1 transcript+, HVP-EBNA2 transcript− | I/II (in vitro) | EBV-associated fatal LPD with VAHS |

*Inoculation of virus-producing cells;

**inoculation of cell-free virus;

***intramuscular inoculation of cell-free virus.

Cyno-EBV, EBV-like virus from Cynomolgus; Si-IIA-EBV, EBV-like virus from HTLV-II-infected cynomolgus cells; HVMF1, Herpesvirus macaca fascicularis 1; ML, malignant lymphoma; NW, New Zealand White; JW, Japanese White; ?, no described data.

As the clinicopathologic features of this rabbit model are very similar to those of fatal childhood EBV-AHS with T-cell LPD 10 or fulminant EBV-positive T-cell LPD following acute/chronic EBV infection, 36 we suggest that this rabbit model of fatal LPD with VAHS, induced by a primary HPV infection, represents an animal model for fulminant EBV-positive T-cell LPD with VAHS due to primary EBV infection. In view of the scarcity and expense of non-human primates, these rabbit models are very useful and inexpensive alternative experimental models for the study of human EBV-AHS pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Reiko Endo, Ms.Yoshiko Sakamoto, Ms. Hiromi Nakamura, Ms. Rika Watanabe, Ms. Mutsumi Okabe, and Ms. Miyuki Shiotani of the Department of Pathology, Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine and Dentistry, and also Mr. Hiroshi Okamoto and Ms. Ai Tomosada of the Central Research Laboratory, Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Kazuhiko Hayashi, M.D., Department of Pathology, Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine and Dentistry, 2–5-1 Shikata-cho, Okayama-city 700-8558, Japan. E-mail: kazuhaya@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Supported by grants (11470058 and 14570190) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan.

References

- 1.Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM: Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s lymphoma. Lancet 1964, 1:702-703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rickinson AB, Kieff E: Epstein-Barr virus. Knipe DM Howley PM eds. Fields Virology. 2001:pp 2575-2627 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

- 3.Weiss LM, Movahed LA, Warnke R, Sklar J: Detection of Epstein-Barr viral genomes in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med 1989, 320:502-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang KL, Chen YY, Shibata D, Weiss LM: Description of an in situ hybridization methodology for detection of Epstein-Barr virus RNA in paraffin-embedded tissues, with a survey of normal and neoplastic tissues. Diagn Mol Pathol 1992, 1:246-255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss LM, Chang KL: Association of the Epstein-Barr virus with hematolymphoid neoplasia. Adv Anat Pathol 1996, 3:1-15 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anagnostopoulos I, Hummel M: Epstein-Barr virus in tumours. Histopathology 1996, 29:297-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawa K: Epstein-Barr virus: associated diseases in humans. Int J Hematol 2000, 71:108-117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Favara BE: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a hemophagocytic syndrome. Semin Diagn Pathol 1992, 9:63-74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su IJ, Hsu YH, Lin MT, Cheng AL, Wang CH, Weiss LM: Epstein-Barr virus-containing T-cell lymphoma presents with hemophagocytic syndrome mimicking malignant histiocytosis. Cancer 1993, 72:2019-2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su IJ, Chen RL, Lin DT, Lin KS, Chen CC: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infects T lymphocytes in childhood EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in Taiwan. Am J Pathol 1994, 144:1219-1225 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su IJ, Wang CH, Cheng AL, Chen RL: Hemophagocytic syndrome in Epstein-Barr virus-associated T-lymphoproliferative disorders: disease spectrum, pathogenesis, and management. Leuk Lymphoma 1995, 19:401-406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kikuta H: Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma 1995, 16:425-429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okano M, Gross TG: Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome and fatal infectious mononucleosis. Am J Hematol 1996, 53:111-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisman DN: Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2000, 6:601-608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mroczek EC, Weisenburger DD, Grierson HL, Markin R, Purtilo DT: Fatal infectious mononucleosis and virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1987, 111:530-535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaffey MJ, Frierson HF, Jr, Medeiros LJ, Weiss LM: The relationship of Epstein-Barr virus to infection-related (sporadic) and familial hemophagocytic syndrome and secondary (lymphoma-related) hemophagocytosis: an in situ hybridization study. Hum Pathol 1993, 24:657-667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita S, Murakami C, Izumi Y, Sawada H, Yamazaki Y, Yokota TA, Matsumoto N, Matsukura S: Severe chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection accompanied by virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome, cerebellar ataxia, and encephalitis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998, 52:449-452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig FE, Clare CN, Sklar JL, Banks PM: T-cell lymphoma and the virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol 1992, 97:189-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolezal MV, Kamel OW, van de Rijn M, Cleary ML, Sibley RK, Warnke RA: Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome characterized by clonal Epstein-Barr virus genome. Am J Clin Pathol 1995, 103:189-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lay JD, Tsao CJ, Chen JY, Kadin ME, Su IJ: Up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α gene by Epstein-Barr virus and activation of macrophages in Epstein-Barr virus-infected T cells in the pathogenesis of hemophagocytic syndrome. J Clin Invest 1997, 100:1969-1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen JS, Tzeng CC, Tsao CJ, Su WC, Chen TY, Jung YC, Su IJ: Clonal karyotype abnormalities in EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Haematologica 1997, 82:572-576 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito E, Kitazawa J, Arai K, Otomo H, Endo Y, Imashuku S, Yokoyama M: Fatal Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with clonal karyotype abnormality. Int J Hematol 2000, 71:263-265 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yagita M, Iwakura H, Kishimoto T, Okamura T, Kunitomi A, Tabata R, Konaka Y, Kawa K: Successful allogeneic stem cell transplantation from an unrelated donor for aggressive Epstein-Barr virus-associated clonal T-cell proliferation with hemophagocytosis. Int J Hematol 2001, 74:451-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falk LA: A review of herpesvirus papio, a B-lymphotropic virus of baboons related to EBV. Comp Immun Microbiol Infect Dis 1979, 2:257-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franken M, Devergne O, Rosenzweig M, Annis B, Kieff E, Wang F: Comparative analysis identifies conserved tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 binding sites in the human and simian Epstein-Barr virus oncogene LMP1. J Virol 1996, 70:7819-7826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yates JL, Camiolo SM, Ali S, Ying A: Comparison of the EBNA1 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus papio in sequence and function. Virology 1996, 222:1-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuentes-Panana EM, Swaminathan S, Ling PD: Transcriptional activation signals found in the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latency C promoter are conserved in the latency C promoter sequences from baboon and rhesus monkey EBV-like lymphocryptoviruses (cercopithicine herpesviruses 12 and 15). J Virol 1999, 73:826-833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenson HB, Ench Y, Gao SJ, Rice K, Carey D, Kennedy RC, Arrand JR, Mackett M: Epidemiology of herpesvirus papio infection in a large captive baboon colony: similarities to Epstein-Barr virus infection in humans. J Infect Dis 2000, 181:1462-1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi K, Ohara N, Teramoto N, Onoda S, Chen HL, Oka T, Kondo E, Yoshino T, Takahashi K, Yates J, Akagi T: An animal model for human EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: herpesvirus papio frequently induces fatal lymphoproliferative disorders with hemophagocytic syndrome in rabbits. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:1533-1542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howe JG, Shu MD: Isolation and characterization of the genes for two small RNAs of herpesvirus papio and their comparison with Epstein-Barr virus-encoded EBER RNAs. J Virol 1988, 62:2790-2798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling PD, Ryon JJ, Hayward SD: EBNA-2 of herpesvirus papio diverges significantly from the type A and type B EBNA-2 proteins of Epstein-Barr virus but retains an efficient transactivation domain with a conserved hydrophobic motif. J Virol 1993, 67:2990-3003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi K, Koirala T, Ino H, Chen H-L, Ohara N, Teramoto N, Yoshino T, Takahashi K, Yamada M, Nii S, Miyamoto K, Fujimoto K, Yoshikawa Y, Akagi T: Malignant lymphoma induction in rabbits by intravenous inoculation of Epstein-Barr virus-related herpesvirus from HTLV-II-transformed cynomolgus leukocyte cell line (Si-IIA). Int J Cancer 1995, 63:872-880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayashi K, Chen H-L, Yanai H, Koirala TR, Ohara N, Teramoto N, Oka T, Yoshino T, Takahashi K, Miyamoto K, Fujimoto K, Yoshikawa Y, Akagi T: Cyno-EBV (EBV-related herpesvirus from cynomolgus macaques) induces rabbit malignant lymphomas and their tumor cell lines frequently show specific chromosomal abnormalities. Lab Invest 1999, 79:823-835 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angiolillo AL, Lamoyi E, Bernstein KE, Mage RG: Identification of genes for the constant region of rabbit T-cell receptor β chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1985, 82:4498-4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isono T, Kim CJ, Seto A: Sequence and diversity of rabbit T-cell receptor γ chain genes. Immunogenetics 1995, 41:295-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, Reyes E, Teruya-Feldstein J, Kingma DW, Sorbara L, Raffeld M, Straus SE, Jaffe ES: Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood 2000, 96:443-451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanegane H, Bhatia K, Gutierrez M, Kaneda H, Wada T, Yachie A, Seki H, Arai T, Kagimoto S, Okazaki M, Oh-ishi T, Moghaddam A, Wang F, Tosato G: A syndrome of peripheral blood T-cell infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) followed by EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma. Blood 1998, 91:2085-2091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagata H, Numata T, Konno A, Mikata I, Kurasawa K, Hara S, Nishimura M, Yamamoto K, Shimizu N: Presence of natural killer-cell clones with variable proliferative capacity in chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Pathol Int 2001, 51:778-785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagata H, Konno A, Kimura N, Zhang Y, Kimura M, Demachi A, Sekine T, Yamamoto K, Shimizu N: Characterization of novel natural killer (NK)-cell and γδ T-cell lines established from primary lesions of nasal T/NK-cell lymphomas associated with the Epstein-Barr virus. Blood 2001, 97:708-713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshioka M, Ishiguro N, Kikuta H. Analysis on latency type of EBV infection in EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Proceeding of 49th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society for Virology, Osaka, 2001, p 251 (in Japanese)

- 41.Callan MF, Steven N, Krausa P, Wilson JD, Moss PA, Gillespie GM, Bell JI, Rickinson AB, McMichael AJ: Large clonal expansions of CD8+ T cells in acute infectious mononucleosis. Nat Med 1996, 2:906-911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayashi K, Ohara N, Koirala TR, Ino H, Chen HL, Teramoto N, Kondo E, Yoshino T, Takahashi K, Yamada M, Tomita N, Miyamoto K, Fujimoto K, Yoshikawa Y, Akagi T: HTLV-II non-integrated malignant lymphoma induction in Japanese white rabbits following intravenous inoculation of HTLV-II-infected simian leukocyte cell line (Si-IIA). Jpn J Cancer Res 1994, 85:808-818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi K, Akagi T: An animal model for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphomagenesis in the human: malignant lymphoma induction of rabbits by EBV-related herpesvirus from cynomolgus. Pathol Int 2000, 50:85-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rickinson AB, Kieff E: Epstein-Barr virus. Fields BN Knipe DM Howley PM eds. Fields Virology. 1996:pp 2397-2446 Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia

- 45.Koirala TR, Hayashi K, Chen H-L, Ino H, Kariya N, Yanai H, Choudhury CR, Akagi T: Malignant lymphoma induction of rabbits with oral spray of Epstein-Barr virus-related herpesvirus from Si-IIA cells (HTLV-II-transformed cynomolgus cell line): a possible animal model for Epstein-Barr virus infection and subsequent virus-related tumors in humans. Pathol Int 1997, 47:442-448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen H-L, Hayashi K, Koirala TR, Ino H, Fujimoto K, Yoshikawa Y, Choudhury CR, Akagi T: Malignant lymphoma induction in rabbits by oral inoculation of crude virus fraction prepared from Ts-B6 cells (cynomolgus B-lymphoblastoid cells harboring Epstein-Barr virus-related simian herpesvirus). Acta Med Okayama 1997, 51:141-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith RD: Is Epstein-Barr virus a human oncogene or only an innocent bystander? Hum Pathol 1997, 28:1333-1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ambinder RF: γ herpesviruses and “hit-and-run” oncogenesis. Am J Pathol 2000, 156:1-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohshima K, Suzumiya J, Kanda M, Kato A, Kikuchi M: Integrated and episomal forms of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in EBV-associated disease. Cancer Lett 1998, 122:43-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimizu N, Tanabe-Tochikura A, Kuroiwa Y, Takada K: Isolation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative cell clones from the EBV-positive Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) line Akata: malignant phenotypes of BL cells are dependent on EBV. J Virol 1994, 68:6069-6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komano J, Maruo S, Kurozumi K, Oda T, Takada K: Oncogenic role of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNAs in Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line Akata. J Virol 1999, 73:9827-9831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruf IK, Rhyne PW, Yang C, Cleveland JL, Sample JT: Epstein-Barr virus small RNAs potentiate tumorigenicity of Burkitt lymphoma cells independently of an effect on apoptosis. J Virol 2000, 74:10223-10228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wutzler P, Meerbach A, Farber I, Wolf H, Scheibner K: Malignant lymphomas induced by an Epstein-Barr virus-related herpesvirus from Macaca arctoides: a rabbit model. Arch Virol 1995, 140:1979-1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrari MG, Rivadeneira ED, Jarrett R, Stevceva L, Takemoto S, Markham P, Franchini G: HV(MNE), a novel lymphocryptovirus related to Epstein-Barr virus, induces lymphoma in New Zealand White rabbits. Blood 2001, 98:2193-2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayashi K, Ohara N, Fujiwara K, Aoki H, Jeon HJ, Takahashi K, Tomita N, Miyamoto K, Akagi T: Co-expression of CD4 and CD8 associated with elevated interleukin-4 in a cord T cell line derived by co-culturing normal human cord leukocytes and an HTLV-II-producing simian leukocyte cell line (Si-IIA). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1993, 119:137-141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohga S, Nomura A, Takada H, Ihara K, Kawakami K, Yanai F, Takahata Y, Tanaka T, Kasuga N, Hara T: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) load and cytokine gene expression in activated T cells of chronic active EBV infection. J Infect Dis 2001, 183:1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]