Abstract

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein in normal rats and rats fed α-naphthylisothiocyanate (ANIT), a compound that causes selective proliferation of epithelial cells (ie, cholangiocytes) that line the bile ducts, was performed. All hepatic structures in ANIT-fed rats branched 1.5 times more often than in normal rats, reflecting an increased number of segments, whereas the length of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein remain unchanged. The length of the proximal vessel segments was uniform in both groups of rats whereas the length of distal segments decreased twofold in ANIT-fed rats, suggesting that small vessels preferentially undergo proliferation. In contrast, the length of all bile duct segments decreased twofold, suggesting that ANIT induced proliferation of all compartments of the biliary tree. The total volume of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein was increased 18, 4, and 3 times, respectively, after ANIT feeding. The diameters of the bile ducts (range, 20 to 259 μm) and arterial (range, 21 to 276 μm) segments in ANIT-fed rats did not differ from normal rats (range, 21 to 245 μm and 20 to 265 μm, respectively). In contrast, the diameters of proximal venous segments in ANIT-fed rats were significantly less (316 ± 68 μm versus 488 ± 89 μm, P < 0.001). The data suggest that after experimentally induced cholangiocyte proliferation, the hepatic artery and portal vein also undergo marked proliferation, presumably to support the increased nutritional and functional demands of the proliferated bile ducts. The molecular mechanisms of these vascular changes remain to be determined.

The liver receives its blood supply from both the hepatic artery and the portal vein, vessels that promptly taper down into many small branches with close association to the biliary tree. Each intrahepatic bile duct is accompanied by a branch of the hepatic artery and is surrounded by a well-developed vascular network, ie, the peribiliary vascular plexus. 1-3 It has been suggested that the peribiliary vascular plexus plays an important role in the physiological function of the biliary epithelia. In particular, it may participate in the transfer of solutes between blood and bile as well as in the supply and drainage of the substances to and from cholangiocytes, the epithelial cells that line the biliary tract. The intimate relationship between the intrahepatic bile ducts and hepatic arteries might also be critically important in the development of hepatobiliary diseases. 4-6

A characteristic of cholangiocytes is their selective proliferation that is observed in many forms of liver injury and under a variety of specific experimental conditions. 1,2,7-9 Anatomical modifications of the hepatic vascular structures, particularly in experimentally induced biliary cirrhosis, have also been documented with most investigators observing predominantly neovascularization of arterial branches. Rearrangement of portal venous branches was also noted under the same conditions, although without agreement as to the nature of these changes. 10-15

We have shown previously that α-naphthylisothiocyanate (ANIT), a compound that induces selective proliferation of cholangiocytes, causes significant architectural alterations of the rat intrahepatic biliary tree, characterized by an increased number of newly formed bile ducts and dramatic volume enlargement. 16 However, no information is available on potential morphological alterations in the hepatic artery and portal vein in this experimental model of selective cholangiocyte proliferation.

Thus, our aim was to examine by three-dimensional X-ray microtomography (ie, micro-CT) anatomical features (ie, length, diameter, volume) as well as patterns of branching in the biliary, arterial, and portal vein networks in normal rats and in rats to whom selective cholangiocyte proliferation was induced by ANIT.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed on male Fisher-344 rats (n = 18) weighing 200 to 220 g. Rats were housed in temperature-controlled rooms (22°C) with 12-hour light/dark cycles. All studies were performed after approval of the Mayo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg bw, ip) and laparotomy was performed. The rats were divided into three groups with three normal and three experimental animals in each. Normal rats were fed a normal laboratory chow diet. Experimental animals were fed a diet containing 0.1% ANIT (70 to 80 mg/kg bw) for up to 28 days. 16

Surgical Procedure

In the first group of animals, the common bile duct was cannulated above the pancreas with PE-10 intramedic polyethylene tubing. In the second group of animals, the hepatic artery was cannulated with a 22-gauge intravenous catheter just below the celiac axis. The superior mesenteric artery, splenic artery, and all nonhepatic branches of the hepatic artery were ligated to ensure that perfusion through the aortic cannula flowed exclusively into the liver; the gastroduodenal artery was not ligated because this vessel feeds the left hepatic artery in approximately one of five animals. The abdominal aorta was clamped above the celiac artery just after perfusion was started. In the third group of rats, the portal vein was cannulated with a 16-gauge intravenous catheter.

In all cases, the liver was first perfused through the hepatic artery or portal vein with a 0.9% sodium chloride solution containing heparin. Immediately after perfusion was started, the inferior vena cava was cut above the diaphragm. When the perfusate draining through the hepatic vein was essentially free of blood and the livers were uniformly blanched, lead chromate-containing radiopaque liquid silicone polymer compound (Microfil) with low viscosity (MV-122; Flow Tech., Inc., Carver, MA) was injected: 1) in the first group of animals into the biliary tree at an infusion rate of 0.01 to 0.05 ml/min and at a pressure of 7 to 10 mmHg); 2) in the second group of animals into the hepatic artery at an infusion rate of 2 ml/min and at a pressure of 60 to 70 mmHg; and 3) in the third group of animals into the portal vein at an infusion rate of 8 to 10 ml/min and at a pressure of 10 to 12 mmHg. These infusion rates and pressures were chosen because they did not exceed the physiological flow and pressure in bile and blood, respectively, in normal rats. Flow rates and pressures were controlled by a perfusion pump (Syringe Infusion Pump, 22; Harvard Apparatus) and a pressure transducer (Recorder 2000; Gould Inc. Instruments System Division), respectively. Once the entire liver had uniformly become yellow, the injection of Microfil was stopped and the dead rat bodies were placed under refrigeration at 4°C overnight to allow polymerization of the compound.

Specimen Preparation

On the following day after complete polymerization of the compound, the liver was dissected into individual lobes and immersed in 10% buffered formalin. To completely dehydrate the liver, at 24-hour intervals each lobe was placed in a solutions of glycerin in water from 30 to 75% and embedded in clear BioPlastic polymer.

Scanning and Reconstruction

Specimens were scanned by a micro-CT scanner developed at Mayo and reconstructed using the modified Feldkamp cone beam backprojection algorithm as described 17 to provide the three-dimensional images of the intrahepatic biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein of normal and ANIT-fed rats.

Analysis of the Reconstructed Image Data

The quantitative analysis of the three-dimensional images of the intrahepatic structures of four liver lobes (left lateral, median, right lateral, and caudate) was performed using the ANALYZE image processing software program (version 7.5; Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Foundation. Rochester, MN). This program allowed computing, displaying, and analyzing orthogonal and oblique sections from the reconstructed volume images. Volume rendering and maximum intensity projections were displayed at various angles of view and threshold voxel values. Average voxel size was 25 to 31 μm and images of up to 600 slices were rendered for each specimen.

Measurements

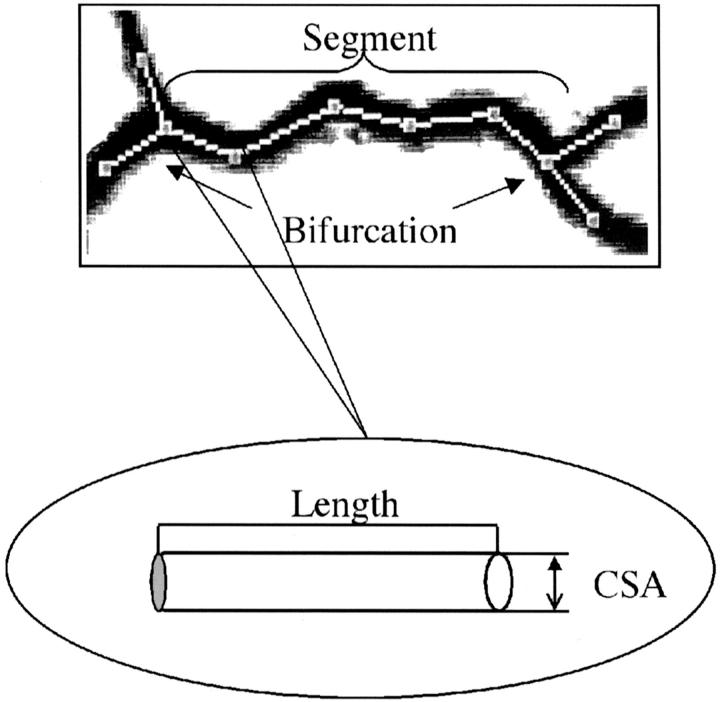

To allow accurate definition of the length and cross-sectional area, measurements were made in terms of bile duct and blood vessel segments. First, the longest (ie, the major) branch of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, or portal vein was selected, manually traced, and divided into interbranch segments. A segment was defined as a part of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, or portal vein between two consecutive branching sites (Figure 1) ▶ . The segments were numbered consecutively, starting from the hilus, and moving to the distal segments. The measurement of the cross-sectional area and the length of the segments were performed as described. 16 The total length of the intrahepatic biliary, portal vein, and hepatic arterial trees was calculated as a sum of length of the individual segments. The volume of the liver lobe and the volume of the hepatic fractions were determined as described. 16

Figure 1.

An example of quantitative analysis performed in the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein in both groups of animals is shown for a bile duct segment from normal rats. A segment is defined to be the part of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, or portal vein between two consecutive branching sites, ie, bifurcations. The trace (white dotted line) was performed at the middle of the segment; the round inset shows a part of segment, ie, a subsegment. Cross-sectional area and the length of each subsegment were measured. The segmental cross-sectional area was taken as the arithmetic average of the subsegmental cross-sectional areas. The length of the each segment was calculated by summing the length of the subsegments.

To describe quantitatively the intrahepatic biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein architecture, the following measurements were performed: 1) the number of segments along the longest branch; 2) the diameter of the bile duct and blood vessel segments; 3) the length of the individual segments; 4) the length of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein along the longest branch; 5) and the volume of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SE as a result of pooling the data of all lobes together into one for the whole liver. Statistical analysis was performed by the Student’s t-test, and results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

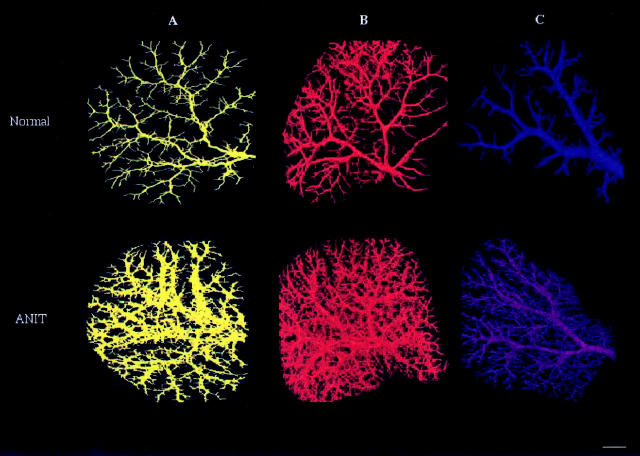

The reconstructed three-dimensional images of the intrahepatic biliary tree, the hepatic artery, and the portal vein of the left lateral lobe of normal (Figure 2 ▶ , top) and ANIT-fed (Figure 2 ▶ , bottom) rats are shown in Figure 2 ▶ ; A, B, and C, respectively. The hepatic structures were visualized under conditions that preserve their original in situ anatomical organization within the parenchyma whereas the individual lobes remained intact. Three-dimensional images of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein after ANIT feeding revealed numerous newly formed, well-organized ducts and vessels originated from pre-existing biliary and vascular branches. All trees are viewed at 80° increments to display in great detail in different planes the branching pattern of the bile ducts and blood vessels and assess their dimensions more precisely by applying segment-by-segment analysis (see Materials and Methods for details).

Figure 2.

The brightest voxel projection of the intrahepatic biliary tree (A), hepatic artery (B), and portal vein (C) from left lateral lobe of normal (top) and ANIT-fed (bottom) rats reconstructed in three dimensions. Images are viewed at 80° increments, but any other axial direction could be selected. The images clearly demonstrate significant bile duct proliferation and hepatic artery and portal vein neovascularization after ANIT feeding. All structures developed well-organized networks connected with pre-existing networks. Scale bar, 2 mm.

Branching Patterns

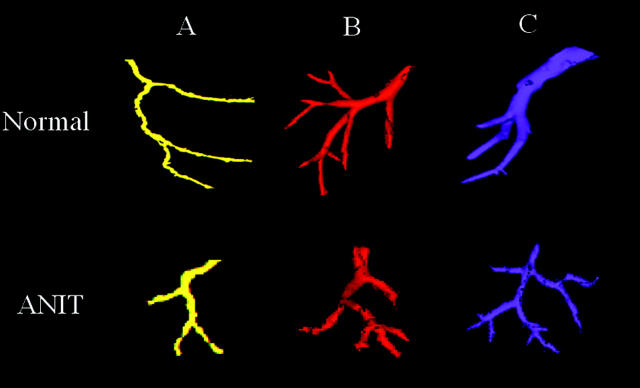

In the biliary tree in control and experimental groups of animals, bifurcation of ducts was the only type of branching. In this branching pattern, each segment divides into two branches only (Figure 3A ▶ , top). This type of branching was also a common pattern in the hepatic artery and the portal vein systems. A less frequent type of branching pattern observed only in the vascular system were trifurcations, when each segment gives rise to three branches (Figure 3, B and C ▶ , top). Trifurcations were found only in distal hepatic arterial and portal venous segments and never in the intrahepatic biliary system. ANIT feeding had no effect on the number of trifurcations in hepatic artery and portal vein (Figure 3 ▶ , bottom).

Figure 3.

Different types of branching patterns in the intrahepatic biliary tree (A), hepatic artery (B), and portal vein (C) in normal (top) and ANIT-fed (bottom) rats. The biliary tree (A) exhibited only one type of branching in which bile duct divides into two branches (bifurcation). This type of branching had also been frequently seen in the hepatic artery and the portal vein. A less frequent type of branching occurs in the hepatic artery (B) and portal vein (C) in which the segment gives rise to three branches, ie, trifurcation. Trifurcations were never seen in the intrahepatic biliary system. ANIT feeding had no effect on number of trifurcations in hepatic artery and portal vein. Scale bar, 0.3 mm.

Number of Segments

The number of interbranch segments along the longest branch of biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein in normal and ANIT-fed rats are shown in Table 1 ▶ . In normal rats the hepatic artery branched more extensively than the biliary tree. After ANIT feeding, the number of branching points along the biliary tree increased two times (P < 0.01) compared to control; the hepatic artery and portal vein bifurcated 1.5 times (P < 0.01) and 1.6 times (P < 0.02), respectively, more often than in normal rats.

Table 1.

Number of Interbranch Segments Along the Longest Branch of the Intrahepatic Biliary Tree, Hepatic Artery, and Portal Vein in Normal and ANIT-Fed Rats

| Liver structure | Number of the interbranch segments | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | ANIT | |

| Biliary tree | 9 (±3) | 17 (±5)* |

| Hepatic artery | 13 (±4) | 21 (±6)* |

| Portal vein | 11 (±4) | 16 (±5)† |

*, P < 0.01 and

†, P < 0.02, compared to normal group.

Length

The length of each interbranch bile duct and vessel segment was calculated as a straight line distance between two consecutive bifurcations. For segments that consisted of subsegments, segmental length was calculated as a sum of the lengths (Figure 1) ▶ . To analyze the anatomical features of the bile duct and vessel segments, we examined the dispersion of length along the longest branches and the length of the individual bile duct and vessel segments within the same segmental order among the networks in both groups of animals.

Table 2 ▶ summarizes mean values of the length for proximal and distal bile duct and vascular segments in normal and ANIT-fed rats. The length of the biliary segments in normal rats did not vary significantly along the course of the major branch. However, after cholangiocyte proliferation induced by ANIT feeding, the length of both proximal and distal segments decreased two times.

Table 2.

Length of the Proximal and Distal Interbranch Segments and Length of the Longest Branch of the Intrahepatic Biliary Tree, Hepatic Artery, and Portal Vein in Normal and ANIT-Fed Rats

| Hepatic structure | Length (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal segments | Distal segments | Longest branch | ||||

| Normal | ANIT | Normal | ANIT | Normal | ANIT | |

| Biliary tree | 1.44 ± (0.39) | 0.72 ± (0.27)* | 1.32 ± (0.38) | 0.63 ± (0.25)* | 14.48 ± (4.9) | 15.32 ± (6.1) |

| Hepatic artery | 1.67 ± (0.62) | 1.49 ± (0.46) | 0.41 ± (0.11) | 0.26 ± (0.05)* | 18.25 ± (5.8) | 19.39 ± (7.9) |

| Portal vein | 1.59 ± (0.54) | 1.45 ± (0.44) | 0.48 ± (0.12) | 0.30 ± (0.06)* | 16.24 ± (6.4) | 17.14 ± (6.8) |

*, P < 0.05 compared to normal biliary tree.

The analysis of length of the individual arterial and portal venous segments revealed remarkable differences compared to bile ducts. The lengths varied significantly, both along the course of the major branch of the vascular trees and within a given segmental order as well (Table 2) ▶ . The length of the arterial and venous segments ranged from 0.24 mm to 2.14 mm and from 0.35 mm to 2.01 mm, respectively. In the experimental group, the length of proximal segments was not changed significantly, whereas the length of the arterial and venous distal segments decreased by ∼1.5 (P < 0.05).

With regard to the distribution of the length of bile ducts within a given segmental order, we noted considerable uniformity in both groups of animals. The variability was narrow; typically two-thirds of the bile duct segments fell within 10 to 17% of the mean value. The distribution of the length of arterial segments was significantly broader (42 to 68% of the mean) than that of bile duct segments. We also found large variations in the lengths of the portal venous segments within the same segmental order; however, the spread (∼ 42% of average value) was less than in the hepatic arterial system. Segments with large and small lengths occur at almost all levels of the vascular network. The vessels with a smaller diameter tend to be relatively shorter.

The lengths of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein along the major branch were calculated as a sum of the lengths of individual bile ducts, arterial segments, and venous segments. As is clear from Table 2 ▶ , the sum of all segments makes the hepatic artery the longest intrahepatic structure in normal rats. ANIT feeding did not affect the length of the biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein.

Diameter

We assumed that the bile duct and blood vessel segments were all circular in cross-section, and cross-sectional area measurements were performed in the middle of the segment. The cross-sectional area was determined by the arithmetic average of subsegmental cross-sectional areas (Figure 1) ▶ . The hepatic structure was followed until the most distal segment was reached or the cross-sectional area of each segment was smaller than a chosen threshold value. The mean values of the diameters of the proximal and distal segments of the biliary, hepatic arterial, and portal venous trees along the longest branch in normal and ANIT-fed rats are shown in Table 3 ▶ .

Table 3.

Diameters of the Proximal and Distal Segments of the Biliary Tree, Hepatic Artery, and Portal Vein in Normal and ANIT-Fed Rats

| Hepatic structure | Diameters (μm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal segments | Distal segments | |||

| Normal | ANIT | Normal | ANIT | |

| Biliary tree | 218.1 ± (38.4) | 195.9 ± (45.3) | 21.3 ± (5.7) | 22.1 ± (6.3) |

| Hepatic artery | 211.8 ± (56.6) | 281.6 ± (54.6) | 22.5 ± (3.6) | 24.6 ± (4.6) |

| Portal vein | 488.1 ± (85.4) | 316.5 ± (83.9)* | 33.6 ± (7.3) | 26.8 ± (5.3) |

*, P < 0.001 compared to normal portal vein.

In normal rats, the proximal portal vein segments possessed a much larger luminal diameter than those in the biliary tree and hepatic artery whereas the diameters of the distal segments of all hepatic structures were comparable. We found no changes in diameters of proximal and distal segments of the intrahepatic biliary tree and hepatic artery in the experimental group of animals. Interestingly, the diameter of the proximal venous segment after ANIT feeding was decreased 1.5 times (P < 0.001) compared to control.

The distribution of the diameters of the bile duct, arterial, and venous segments within each given segmental order was narrow in both groups of animals; typically, two-thirds of bile duct and blood vessel segments fell within 15 to 20% of the average value.

Volume

Using a micro-CT scanner, volume of the whole liver and, in particular, the hepatic artery, the portal vein, and the biliary system in normal and ANIT-fed rats was assessed. To compare the accuracy of our measurements, the volume of the whole liver was also experimentally determined at postmortem examination by fluid displacement and the volumes of the biliary and vascular trees assessed by the amount of Microfil injected. The amount of contrast medium in the syringe at the beginning and at the end of the infusion was measured; this difference represented the volume of the particular liver structure. The volume of the given hepatic structure obtained by three-dimensional reconstruction was generally somewhat less (7 to 11%) than the volume of this structure determined by the amount of contrast medium injected.

The total liver tissue volume assessed by micro-CT scanning was 10.22 ± 3.12 ml in normal rats and 9.67 ± 2.24 ml in ANIT-fed rats, respectively, versus 11.04 ± 2.08 ml and 8.73 ± 1.89 ml, as measured by saline displacement technique, suggesting precise measurements. The results of volume determinations of the entire intrahepatic biliary, arterial, and portal vein systems in normal and ANIT-fed rats are given in Table 4 ▶ . The intrahepatic biliary tree in normal rats displays the smallest total volume compared to hepatic artery and portal vein volumes. After ANIT feeding, volumes of all analyzed hepatic structures was significantly increased. It has been shown that ANIT feeding in rats results in weight loss during the first 3 weeks and then remains constant up to 6 weeks. 18,19 In contrast to body weight, liver weight is increased. We found that ANIT triggered significant increases in the volumes of the intrahepatic biliary tree, hepatic arterial, and portal venous systems. Thus, we speculate that the increase in liver weight in ANIT-fed rats is because of marked bile duct proliferation and blood vessel neovascularization.

Table 4.

Volume of the Intrahepatic Biliary Tree, Hepatic Artery, and Portal Vein in Normal and ANIT-Fed Rats

| Liver structure | Volume (μl) | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | ANIT | |

| Biliary tree | 48.53 ± (11.01) | 873.56 ± (146.17)* |

| Hepatic artery | 398.58 ± (91.53) | 1747.82 ± (343.32)* |

| Portal vein | 550.07 ± (123.17) | 1476.64 ± (294.71)* |

*, P < 0.001 compared to normal group.

Discussion

The present study used a novel imaging technique to examine the three-dimensional architecture of the intrahepatic biliary, arterial, and portal vein systems in normal rats and in rats with experimentally induced selective cholangiocyte proliferation after ANIT feeding. By comparison of key anatomical parameters (ie, length, diameter, branching patters, volume) in both groups of animals, we conclude that ANIT feeding triggered significant changes not only in the biliary tree, as previously reported, 16 but also induced neovascularization of the hepatic artery and portal vein branches characterized by: 1) markedly enlarged volumes; 2) increased number of bifurcation points along the length of the hepatic structures; and 3) decreased length of the interbranch segments. Newly formed bile ducts form a well-organized three-dimensional network and remain connected with the pre-existing network. A similar three-dimensional neovascularization was also observed in both the hepatic artery and portal vein.

Among the three analyzed intrahepatic structures, the biliary tree in normal rats comprises the smallest portion of the total liver volume, which markedly increases after ANIT feeding. The expanded mass of proliferated biliary tree theoretically requires an increased vascular supply to support the newly formed bile ducts. Indeed, significantly enlarged hepatic artery and portal vein volumes after ANIT feeding presumably supply additional nutrients, oxygen, and growth factors to the expanded biliary tree.

The results of our study confirm a number of observations made previously and also represent new quantitative information about the anatomical features of the intrahepatic biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein in normal and ANIT-fed rats. The diameters of bile ducts, hepatic arterial, and portal venous segments in normal rats as well as diameters of bile ducts and hepatic arterial segments in rats with selective cholangiocyte proliferation observed in our study are comparable to those in the literature. 16,20-22 We found that the diameters of portal vein segments significantly decreased after ANIT feeding whereas the segmental diameters of the hepatic arterial network remained unchanged. Although the explanation for this difference in vascular response of the portal vein and hepatic artery is not clear from our work, it may reflect the fact that the portal vein has a thin wall and lower blood pressure, and therefore, may be easily compressed by expanded surrounding tissue. On the other hand, despite the decreased diameter of portal venous segments in response to ANIT feeding, the volume of the portal vein markedly increased because of formation of new blood vessel branches.

Our data on the lengths of the interbranch intrahepatic bile duct, arterial, and portal venous segments as well as the length of these hepatic structures along the longest branch are novel. Segmental length may be an important anatomical parameter reflecting both the branching and the growth patterns of networks during growth and maturation of the intrahepatic structures under normal conditions or structural modifications during abnormal development. As we have shown, a clear anatomical reorganization of the intrahepatic biliary tree, hepatic artery, and portal vein occurs after ANIT feeding. 16 In particular, cholangiocyte proliferation provoked by ANIT was associated with a twofold decrease in the length of proximal and distal bile duct segments, suggesting that all segments of the biliary tree are involved in the process of proliferation. In contrast, our data show decreased lengths only of the distal segments of the vascular structures in response to ANIT feeding suggesting that preferentially small blood vessels undergo proliferation in hepatic artery and portal vein.

Despite growing data on conditions in which bile duct proliferation and hepatic artery neovascularization occur, information regarding chronological rearrangement of the hepatic microvasculature as a consequence of the bile duct proliferation is limited. It has been shown that after common bile duct ligation both events, bile duct proliferation and hepatic artery neovascularization, occur at different time points and bile duct proliferation seems to be a prerequisite for angiogenesis; cholangiocyte proliferation reached a plateau at 3 days whereas vascular endothelial cell proliferation was observed 1 week later. 12,15,23 To our knowledge, no published data exist on whether the veins or arteries proliferate first.

A number of studies suggest that a variety of factors or inducers may be involved in both cholangiocyte proliferation and accompanying angiogenesis. First, factors may exist that specifically act on biliary epithelia and vascular endothelia. To date, no cholangiocyte-specific growth factors have been identified 1,2,7,8 while several angiogenic growth factors have been characterized, including members of the vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor families. Nonspecific factors that can directly activate a variety of target cells may also be important. Indeed, several growth factors and chemokines have been implicated in the process of proliferation and neovascularization but their precise contribution is unclear. Finally, indirect-acting factors that trigger the release of direct-acting molecules from macrophages, hepatocytes, and bile duct epithelial or endothelial cells 24-28 are potentially important but remain as yet unidentified.

Based on published data suggesting that biliary tree proliferation precedes the vascular response by more than a week, and on our data showing that extensive neovascularization accompanied selective cholangiocyte proliferation, we speculate that bile duct hyperplasia triggers the release of as yet unknown molecular signals from cholangiocytes or other cells to promote blood vessel neovascularization. Thus, cholangiocyte proliferation may represent a physiological stimulus for angiogenesis, enhancing the production of directly acting angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor 24-26 receptor of which is known to be expressed in cholangiocytes 27 and hepatocytes 28 or production of indirectly acting cytokines or growth factors produced by cholangiocytes such as epidermal growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, and transforming growth factor 29-33 because it is known that they are able to stimulate vascular endothelial growth factor expression in specific cell types. 34-36 However, further studies are necessary to understand the molecular mechanisms of crosstalk between proliferated cholangiocytes and adjacent vascular endothelia.

In conclusion, the anatomical phenotypes of the three analyzed hepatic structures by our approach clarified almost certainly reflect specific and perhaps different molecular morphogenic regulatory processes that currently represent a totally obscure fruitful area of study.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Nicholas F. LaRusso, M.D., Mayo Medical School, Clinic, and Foundation, 200 First St., SW, Rochester, MN 55905. E-mail: larusso.nicholas@mayo.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants DK24031 to N. F. L. and RR11800 to E. L. R.) and by the Mayo Foundation.

References

- 1.LaRusso NF: Morphology, physiology and biochemistry of biliary epithelia. Toxicol Pathol 1996, 24:84-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpini G, Phillips JO, LaRusso NF: The biology of biliary epithelia. Arias IM Boyer JL Fausto N Jakoby WB Schachter DA Shafritz DA eds. The Liver: Biology and Pathobiology 1994:pp 623-653 Raven Press, Ltd. New York

- 3.Yamamoto K, Itoshima T, Tsuji T, Murakami T: Three-dimensional fine structure of the biliary tract: scanning electron microscopy of the biliary casts. J Electron Microsc Tech 1988, 14:208-217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi S, Nakanuma Y, Matsui O: Intrahepatic peribiliary vascular plexus in various hepatobiliary diseases: a histological survey. Hum Pathol 1994, 25:940-946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kono N, Nakanuma Y: Ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies of the intrahepatic peribiliary capillary plexus in normal livers and extrahepatic biliary obstruction in human beings. Hepatology 1992, 15:411-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherman IA, Pappas SC, Fisher MM: Hepatic microvascular changes associated with development of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Am J Physiol 1990, 258:H460-H465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvaro D, Gigliozzi A, Attili AF: Regulation and deregulation of cholangiocyte proliferation. J Hepatol 2000, 33:333-340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeSage G, Glaser S, Alpini G: Regulation of cholangiocytes proliferation. Liver 2001, 21:73-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao D, Zimmermann A, Wheatley AM: Morphometry of the liver after liver transplantation in the rat: significance of an intact arterial supply. Hepatology 1993, 17:310-317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto T, Kobayashi T, Phillips MJ: Perinodular arterial plexus in liver cirrhosis. Scanning electron microscopy of microvascular casts. Liver 1984, 4:50-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terada T, Ishida F, Nakanuma Y: Vascular plexus around intrahepatic bile ducts in normal livers and portal hypertension. J Hepatol 1989, 8:139-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haratake J, Hisaoka M, Yamamoto O, Horie A: Morphological changes of hepatic microcirculation in experimental rat cirrhosis: a scanning electron microscopic study. Hepatology 1991, 13:952-956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaudio E, Pannarale L, Onori P, Riggio O: A scanning electron microscopic study of liver microcirculation disarrangement in experimental rat cirrhosis. Hepatology 1993, 17:477-485 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano S, Haratake J, Hashimoto H: Alterations in bile ducts and peribiliary microcirculation in rats after common bile duct ligation. Hepatology 1995, 21:1380-1386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaudio E, Onori P, Pannarale L, Alvaro D: Hepatic microcirculation and peribiliary plexus in experimental biliary cirrhosis: a morphological study. Gastroenterology 1996, 111:1118-1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masyuk TV, Ritman EL, LaRusso NF: Quantitative assessment of the rat intrahepatic biliary system by three-dimensional reconstruction. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:2079-2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen SM, Demirkaya O, Ritman E: Three-dimensional imaging of vasculature and parenchyma in intact rodent organs with X-ray micro-CT. Am J Physiol 1998, 275:H1103-H1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards WL, Tsukada Y, Potter VR: γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase and α-fetoprotein expression during α-naphthylisothiocyanate-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Cancer Res 1982, 42:5133-5138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonard TB, Popp JA, Graichen ME, Dent JG: α-Naphthylisothiocyanate induced alteration in hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes and liver morphology: implications concerning anticarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 1981, 2:473-482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demachi H, Matsui O, Takashima T: Scanning electron microscopy of intraheparic microvasculature casts following experimental hepatic artery embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1991, 14:158-162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benedetti A, Bassotti C, Rapino K, Marucci L, Jezequel AM: A morphometric study of the epithelium lining the rat intrahepatic biliary tree. J Hepatol 1996, 24:335-342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alpini G, Glaser SS, Ueno Y, Pham L, Podila PV, Caligiuri A, LeSage G, LaRusso NF: Heterogeneity of the proliferative capacity of rat cholangiocytes after bile duct ligation. Am J Physiol 1998, 274:G767-G775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosmorduc O, Wendum D, Corpechot C, Galy B, Sebbagh N, Raleigh J, Housset C, Poupon R: Hepatocellular hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression and angiogenesis in experimental biliary cirrhosis. Am J Pathol 1999, 155:1065-1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosmorduc O, Wendum D, Galy B, Huez I, Prat H, de Saint-Maur PP, Poupon R: Expression of the angiogenic factors basic FGF and VEGF in human cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 1996, 24:341A [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. EMBO J 1999, 13:9-22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liekens S, De Clercq E, Neyts J: Angiogenesis: regulators and clinical applications. Biochem Pharmacol 2001, 61:253-270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaudio E, Barbaro B, Glaser S, Alvaro D, Franchitto A, Ueno Y, Francis H, Marzioni M, Rashid S, Phinizy JL, LeSage G, Alpini G: Chronic administration of recombinant VEGF-A prevents bile duct loss due to inhibition of proliferation and activation of apoptosis of cholangiocytes following hepatic artery ligation. Hepatology 2002, 36:223A [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taniguchi E, Sakisaka S, Matsuo K, Tanikawa K, Sata M: Expression and role of vascular endothelial growth factor in liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats. J Histochem Cytochem 2001, 49:121-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milani S, Herbst H, Schuppan D, Stein H, Surrenti C: Transforming growth factors beta 1 and beta 2 are differentially expressed in fibrotic liver disease. Am J Pathol 1991, 139:1221-1229 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saperstein LA, Jirtle RL, Farouk M, Thompson HJ, Chung KS, Meyers WC: Transforming growth factor-beta 1 and mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor expression during intrahepatic bile duct hyperplasia and biliary fibrosis in the rat. Hepatology 1994, 19:412-417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polimeno L, Azzarone A, Zeng QH, Panella C, Subbotin V, Carr B, Bouzahzah B, Francavilla A, Srarzl TE: Cell proliferation and oncogene expression after bile duct ligation in the rat: evidence of a specific growth effect on bile duct cells. Hepatology 1995, 21:1070-1088 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, Sakamoto T, Ezure T, Yokomuro S, Murase N, Michalopoulos G, Demetris AJ: Interleukin-6, hepatocyte growth factor, and their receptors in biliary epithelial cells during a type I ductular reaction in mice: interaction between the periductal inflammatory and stromal cells and the biliary epithelium. Hepatology 1998, 28:1260-1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park J, Gores G, Patel T: Lipopolysaccharide induces cholangiocytes proliferation via an interliukin-6-mediated activation of p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Hepatology 1999, 29:1037-1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brogi E, Wu T, Namiki A, Isner JM: Indirect angiogenic cytokines upregulate VEGF and bFGF gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells, whereas hypoxia upregulates VEGF expression only. Circulation 1994, 90:649-652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pertovaara L, Kaipainen A, Mustonen T, Orpana A, Ferrara N, Saksela O, Alitalo K: Vascular endothelial growth factor is induced in response to transforming growth factor-beta in fibroblastic and epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:6271-6274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkenzeller G, Technau A, Marme D: Hypoxia-induced transcription of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene is independent of functional AP-1 transcription factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995, 208:432-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]