Abstract

Tocopherols are lipophilic antioxidants that are synthesized exclusively in photosynthetic organisms. In most higher plants, α- and γ-tocopherol are predominant with their ratio being under spatial and temporal control. While α-tocopherol accumulates predominantly in photosynthetic tissue, seeds are rich in γ-tocopherol. To date, little is known about the specific roles of α- and γ-tocopherol in different plant tissues. To study the impact of tocopherol composition and content on stress tolerance, transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants constitutively silenced for homogentisate phytyltransferase (HPT) and γ-tocopherol methyltransferase (γ-TMT) activity were created. Silencing of HPT lead to an up to 98% reduction of total tocopherol accumulation compared to wild type. Knockdown of γ-TMT resulted in an up to 95% reduction of α-tocopherol in leaves of the transgenics, which was almost quantitatively compensated for by an increase in γ-tocopherol. The response of HPT and γ-TMT transgenics to salt and sorbitol stress and methyl viologen treatments in comparison to wild type was studied. Each stress condition imposes oxidative stress along with additional challenges like perturbing ion homeostasis, desiccation, or disturbing photochemistry, respectively. Decreased total tocopherol content increased the sensitivity of HPT:RNAi transgenics toward all tested stress conditions, whereas γ-TMT-silenced plants showed an improved performance when challenged with sorbitol or methyl viologen. However, salt tolerance of γ-TMT transgenics was strongly decreased. Membrane damage in γ-TMT transgenic plants was reduced after sorbitol and methyl viologen-mediated stress, as evident by less lipid peroxidation and/or electrolyte leakage. Therefore, our results suggest specific roles for α- and γ-tocopherol in vivo.

Under natural conditions, plants are exposed to a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses, including pathogens, adverse temperature, drought, salt, and high light. Under these stress conditions, reactive oxygen species (ROS) derived from molecular oxygen can accumulate in leaves, resulting in the oxidation of cellular components, including proteins, chlorophyll, and lipids. To cope with oxidative stress plants have evolved two general protective mechanisms, enzymatic and nonenzymatic detoxification, of which the latter involves vitamin E (Dat et al., 2000; Alscher and Heath, 2002).

Eight structurally related tocochromanols are commonly addressed as vitamin E, namely tocopherols and tocotrienols, which can be distinguished by the saturation of their prenyl moiety and by the methylation degree of their chromonal ring. Subcellular distribution and enzymatic steps of vitamin E biosynthesis have been characterized in detail (for recent review, see DellaPenna and Pogson, 2006) and a number of molecular approaches to manipulate vitamin E synthesis have been published (summarized in Herbers, 2003; DellaPenna and Last, 2006; Dörmann, 2007).

Vitamin E synthesis is restricted to photosynthetic organisms including plants, algae, and some cyanobacteria. The first committed steps in tocopherol and tocotrienol biosynthesis are the prenylation of homogentisic acid by either phytyl diphosphate or geranylgeranyl diphosphate yielding 2-methyl-6-phytyl-benzoquinone or methyl geranylgeranyl benzoquinone, respectively. These reactions are catalyzed by homogentisate phytyltransferase (HPT) and homogentisate geranylgeranyl transferase. The two subsequent steps catalyzed by tocopherol cyclase (TC) and γ-tocopherol methyltransferase (γ-TMT) are in common for tocopherol and tocotrienol biosynthesis (see Fig. 1). With the recent characterization of phytol and phytyl phosphate kinase from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Ischebeck et al., 2006; Valentin et al., 2006), it could be demonstrated that the prenyl moiety for γ-tocopherol biosynthesis is derived from free phytol in seeds, substantiating the assumption that phytol gets recycled during chlorophyll breakdown (Peisker et al., 1989; Rise et al., 1989; Dörmann, 2007).

Figure 1.

The tocopherol, tocotrienol, and plastoquinone biosynthetic pathway in plants. This figure represents the enzymatic reactions and intermediates that are involved in the biosynthesis of tocopherol, tocotrienol, and plastoquinone. Arabidopsis mutants of the corresponding pathway genes are given in parentheses behind the enzymes. DMPBQ, 2,3-dimethyl-5-phytyl-1,4-benzoquinone; HPP, p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate; MSBQ, 2-methyl-6-solanesyl-1,4-benzoquinone; phytyl-DP, phytyl-diphosphate; solanesyl-DP, solanesyl diphosphate; HPPD, HPP dioxygenase; HST, homogentisate solanesyltransferase; MPBQMT (vte3), MPBQ/MSBQ methyltransferase; PK (vte5), phytol kinase; PPK, phytyl phosphate kinase.

In plants, tocopherol composition differs between different species and between different tissues within one species (summarized in Grusak and DellaPenna, 1999). Usually, leaves commonly accumulate α-tocopherol, whereas seeds are rich in γ-tocopherol. β- and δ-tocopherol are not very abundant in most plant species. Therefore, α-tocopherol has been proposed to participate in the detoxification of ROS together with the hydrophilic antioxidants glutathione and ascorbate (Foyer and Noctor, 2003). Based on inhibitor studies it has been shown that tocopherol acts as singlet oxygen scavenger in PSII of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Trebst et al., 2002; Kruk et al., 2005). The inhibitory effect could be overcome by addition of membrane-permeable short chain α- and γ-tocopherol derivatives, suggesting that α-tocopherol can be substituted by γ-tocopherol in leaves. A similar conclusion was drawn from the biochemical analysis of the Arabidopsis γ-TMT-deficient mutant vte4-1, which accumulates comparable amounts of γ-tocopherol instead of α-tocopherol (Bergmüller et al., 2003). Photosynthetic parameters in vte4-1 were found to be indistinguishable from wild type under a variety of stress conditions (Bergmüller et al., 2003). In contrast to leaves, γ-tocopherol is predominant in seeds, where total tocopherol contents are 10 to 100 times higher than in leaves (Table I). In oil-storing seeds like Arabidopsis, γ-tocopherol has been shown to protect polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) from oxidation, thereby increasing seed longevity (Sattler et al., 2004). This suggests that γ-tocopherol is involved in desiccation tolerance of seeds.

Table I.

Tocopherol content and composition in tobacco tissues

Tocopherols were extracted from the indicated tobacco tissues with 100% methanol as described in “Materials and Methods.” α-T and γ-T are α- and γ-tocopherol, respectively; β-tocopherol was not detectable and δ-tocopherol represented less than 5% of the tocopherol pool and was omitted from the representation for clarity reasons. Consequently, the percentage distribution of α- versus γ-tocopherol is given in the table, being mean and sd of four independent samples.

| Plant Tissue | Total Tocopherol (μg/g Fresh Weight) | % of α-T | % of γ-T |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetative tissues | |||

| Seedling | 27.4 ± 4.3 | 96.1 ± 3.9 | 3.9 ± 3.1 |

| Mature leaf | 32.4 ± 7.3 | 94.6 ± 4.5 | 5.4 ± 4.1 |

| Senescent leaf | 39.3 ± 6.5 | 92.4 ± 3.6 | 7.6 ± 3.1 |

| Root | 20.7 ± 2.1 | 93.2 ± 4.2 | 6.7 ± 4.1 |

| Flower organs | |||

| Sepals | 28.5 ± 6.4 | 51.7 ± 3.4 | 48.3 ± 3.1 |

| Petals | 15.1 ± 8.7 | 37.4 ± 3.1 | 62.6 ± 3.2 |

| Stamen | 45.7 ± 10.7 | 20.6 ± 4.2 | 79.4 ± 4.4 |

| Carpel | 46.6 ± 13.7 | 77.9 ± 11.7 | 22.1 ± 11.1 |

Excess salt and sorbitol both induce hyperosmotic and oxidative stress, albeit to varying degrees. Consequently, molecular events in response to salt and osmotic stress are convergent, involving abscisic acid (ABA), ROS, and Ca2+ signaling that activate various downstream signaling cascades, like mitogen-activated protein kinases, Suc nonfermenting-related kinase, or calcineurin B-like Ca2+-dependent signaling (for recent reviews, see Wang et al., 2003; Boudsocq and Laurière, 2005). The interplay of the foliar antioxidant network and cellular signaling is pivotal for stress sensing. Leaf ascorbate content was shown to modulate the response to ABA (Pastori et al., 2003), while ABA was shown to stimulate antioxidant capacity and transient ROS production in parallel (Zhang et al., 2006, and refs. therein). As proposed by Foyer and Noctor (2005), the balance of the antioxidant and ROS responses finally determines whether the cells respond to water stress by acclimation and hardening or with programmed cell death.

Nevertheless, excess salt and sorbitol are thought to have different impact on cellular metabolism. After its uptake into the symplast, sodium will be sequestered in the vacuole by Na+/H+ antiporters (Fukuda et al., 1999; Gaxiola et al., 1999; Shi et al., 2000) to prevent poisoning of enzyme activities in the other cellular compartments (Serrano et al., 1999). As this process utilizes the pH gradient across the tonoplast, high salinity also impairs cellular pH homeostasis (Serrano et al., 1999). In contrast, sorbitol accumulates as compatible solute in Rosaceae (e.g. apple [Malus domestica]; Li and Li, 2005; Sircelj et al., 2005) and prokaryotes and possesses a lower toxicity than NaCl. Sorbitol accumulation of up to 3 μmol g fresh weight−1 was tolerated in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Sheveleva et al., 1998). Excess sorbitol more specifically effectuates desiccation of the cellular compartments, inevitably leading to increased ROS production at the photosystem reaction centers when the hydration status in chloroplasts drops. Consequently, increasing ROS quenching capacity by overexpression of superoxide dismutase (Gupta et al., 1993) or glutathione S-transferase and glutathione peroxidase (Roxas et al., 1997) had the potential to alleviate oxidative stress.

In this study, we have constitutively silenced HPT and γ-TMT posttranscriptionally in tobacco plants with a dsRNAi approach. Assessing the response of HPT and γ-TMT knockdown lines to salt stress, sorbitol stress, and methyl viologen enabled us to compare the effects of a general tocopherol deficiency (in HPT:RNAi) versus a replacement of α-tocopherol with γ-tocopherol (in γ-TMT:RNAi) in oxidative stress scenarios. Silencing of both HPT and γ-TMT resulted in an elevated susceptibility to salt stress. In contrast, the substitution of α- for γ-tocopherol in γ-TMT transgenics resulted in an elevated osmotolerance when plantlets were subjected to sorbitol. This was characterized by substantially increased membrane integrity compared to the wild type, as determined by ion leakage and lipid peroxidation. The γ-TMT:RNAi plants exhibited a similar benefit when ROS production in the thylakoids was increased by methyl viologen treatment. Our results provide evidence that γ-tocopherol is more potent than α-tocopherol in mediating osmoprotection in vivo.

RESULTS

The Ratio of α- to γ-Tocopherol Is Tissue Dependent in Tobacco

To investigate the plasticity of tocopherol biosynthesis in tobacco, we examined the composition of the tocopherol pool in a variety of vegetative and reproductive organs of wild-type Samsun NN (Table I). The tocopherol pool in seedlings, leaves, roots, and stigma consisted more than 90% of α-tocopherol, female flower organs contained between 70% and 80% α-tocopherol, sepals and petals contained roughly equal amounts of α- and γ-tocopherol, while stamina (80% γ-tocopherol) were dominated by γ-tocopherol. Both total tocopherol pool size and the fraction of γ-tocopherol increased progressively with seed maturation (data not shown). The tocochromanol pool in mature tobacco seeds is dominated by γ-tocopherol and γ-tocotrienol with negligible amounts of α-tocopherol (e.g. Falk et al., 2003).

In summary, α-tocopherol accumulates in vegetative organs of tobacco, while reproductive tissues are enriched in γ-tocopherol, especially when they are desiccation tolerant like stamina or seeds.

dsRNAi-Mediated Silencing of HPT Results in Tocopherol Deficiency in Tobacco Plants

To manipulate tocopherol metabolism in transgenic tobacco, potato (Solanum tuberosum) cDNA fragments of StHPT and Stγ-TMT (see next paragraph) were introduced into intron-spliced hairpin RNA (RNAi) silencing constructs driven by the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (Figs. 2A and 3A). Posttranscriptional silencing of tobacco HPT mediated by pBin-StHPT-RNAi (Fig. 2A) resulted in 68 primary transformants in the T0 generation, which were selected for kanamycin resistance. All positive lines were transferred to the greenhouse and screened for tocopherol deficiency by HPLC analysis. Tocopherol content in the transgenic lines ranged from more than 130% to less than 2% of wild type (data not shown), demonstrating efficient silencing of tobacco HPT by the heterologous potato dsRNAi construct. HPT catalyzes the committed step in tocopherol biosynthesis, the condensation of the precursors homogentisic acid and phytyl diphosphate (see Fig. 1). Therefore, silencing of HPT affected all tocopherols to the same extent, leaving the ratio between individual tocopherols constant (data not shown).

Figure 2.

RNAi-mediated silencing of HPT results in tocopherol deficiency in transgenic tobacco plants. A, Representation of the T-DNA from the binary intron-spliced hairpin RNA (RNAi) expression construct used for transformation of tobacco plants. The 650-bp StHPT PCR fragment from the potato EST (accession no. BI919738) was cloned between the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and the ocs terminator of the Bin19-derived vector in sense and antisense orientation, separated by intron 1 of potato GA 20-oxidase (200 bp) using the introduced BamHI and SalI restriction sites. B, The total tocopherol content (α-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol) in fully expanded leaves of HPT:RNAi transformants and wild type was quantified fluorometrically by HPLC and normalized to fresh weight.

Figure 3.

RNAi-mediated silencing of γ-TMT lead to accumulation of γ-tocopherol and a deficiency in α-tocopherol in transgenic tobacco plants. A, Representation of the T-DNA from the binary intron-spliced hairpin RNA (RNAi) expression construct used for transformation of tobacco plants. The 625-bp Stγ-TMT PCR fragment from the potato EST (accession no. BQ116842) was cloned between the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and the ocs terminator of the Bin19-derived vector in sense and antisense orientation, separated by intron 1 of potato GA 20-oxidase (200 bp) using the introduced BamHI and SalI restriction sites. B to D, Contents of tocopherols in fully expanded leaves of γ-TMT:RNAi transformants and wild type were determined by HPLC. The transgenic plant lines are ordered from left to right with increasing α- to γ-tocopherol ratio. B, α-Tocopherol content. C, γ-Tocopherol content. D, Total tocopherol content (sum of α-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol). E, The ratio of α- to γ-tocopherol in wild-type and transgenic plants. The diagrams depict data of single measurements for individuals selected for further study in the T0 generation screening. The data were later reproduced with all tested individuals of the lineage progenies.

Five transgenic lines with the strongest tocopherol deficiency lacking more than 97% of total tocopherol (StHPT:RNAi-28, -49, -35, -44, -2), one line with 70% reduction (StHPT:RNAi-39) and one with almost 40% reduction (StHPT:RNAi-65) were selected for further analysis (Fig. 2B). Among the selected lines, StHPT:RNAi-28 showed the strongest depletion of total tocopherol with less than 2% of wild-type levels. Transgenics with a total tocopherol content of less than 5% of wild type, e.g. StHPT:RNAi-28, -44, and -49, exhibited a significant growth reduction of about 30% when cultivated in the greenhouse (Table II), while growth of HPT:RNAi plants with a residual tocopherol content of above 5% were indistinguishable from the wild type. For simplicity, only results for the strongest line StHPT:RNAi-28 will be communicated below.

Table II.

Growth performance of the three strongest HPT:RNAi tobacco lines (HPT) in comparison to the wild type (WT)

The parameters were recorded at the end of the vegetative phase and are means and sd of five individuals of one representative population.

| Plant Line | Shoot Length

|

Fresh Weight

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | % of WT | Biomass | % of WT | |

| cm | g | |||

| WT | 92.6 ± 3.76 | 100 | 157.2 ± 13.4 | 100 |

| HPT:RNAi-44 | 80.4 ± 3.5 | 86.1 ± 3.8 | 124.2 ± 9.4 | 78.9 ± 5.7 |

| HPT:RNAi-49 | 68.4 ± 8.3 | 73.8 ± 9.0 | 115 ± 9.2 | 73.7 ± 5.8 |

| HPT:RNAi-28 | 62.1 ± 6.7 | 66.9 ± 7.2 | 107.7 ± 9.4 | 68.5 ± 5.9 |

Silencing of the Tobacco γ-TMT Gene by dsRNAi Results in an Accumulation of γ- Instead of α-Tocopherol in Leaves

Transforming the pBin-Stγ-TMT-RNAi construct (Fig. 3A) for constitutive silencing of γ-TMT into tobacco yielded 82 kanamycin-resistant T0 transformants, in which the tocopherol composition was surveyed by HPLC. Silencing of γ-TMT lead to diminished α-tocopherol contents in leaves of the transgenics. The T0 transformant Stγ-TMT:RNAi-55 showed the strongest α-tocopherol-deficient phenotype with less than 5% of α-tocopherol wild-type levels (Fig. 3B). Stγ-TMT:RNAi-82 and -22 were also strongly affected, accumulating 7% to 10% of wild-type α-tocopherol, respectively.

The reduction in α-tocopherol was mostly paralleled by an increase in γ-tocopherol in the γ-TMT transformants (Fig. 3C), so that strong silencing of γ-TMT correlated with a decrease of the α- to γ-tocopherol ratio in leaves of the transgenics (Fig. 3E). The intermediate lines Stγ-TMT:RNAi-1, -21, and -13 displayed equal contents of α- and γ-tocopherol, while the three lines with the most dramatic change in the ratio of α- to γ-tocopherol (to far below 1), namely Stγ-TMT:RNAi-55, -82, and -22 (see Fig. 3E), were selected for closer study. For comparison, the wild type displayed an α- to γ-tocopherol ratio of about 15 (Fig. 3E).

In the lines Stγ-TMT:RNAi-22, -55, and -82, total tocopherol contents remained rather unchanged in relation to the wild type (Fig. 3D), resulting in a net substitution of α- for γ-tocopherol in leaves. The strongest line Stγ-TMT:RNAi-55 was characterized in more detail along with StHPT:RNAi-28, as described below.

Silencing of γ-TMT Results in Increased Biomass Production under Osmotic Stress, while Silencing of Both HPT and γ-TMT Decreases Tolerance to Salt Stress

In contrast to recent reports on the functional characterization of plants with altered tocopherol composition (Porfirova et al., 2002; Bergmüller et al., 2003; Hofius et al., 2004; Havaux et al., 2005; Kanwischer et al., 2005; Maeda et al., 2006), we aimed at examining the oxidative and osmotic stress tolerance instead of focusing on high light and cold stress. Wild-type tobacco and the transgenics were grown on Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with increasing amounts of 0 to 400 mm sorbitol or sodium chloride in axenic culture; plant growth (this section), metabolite contents, and physiological parameters (other paragraphs) were scored after 4 weeks of either stress.

Biomass production of wild-type plants negatively correlated with increasing sorbitol or NaCl concentrations and was diminished by 90% and 65% on 400 mm sorbitol and 400 mm sodium chloride, respectively (Tables III and IV, column 1). Vegetative growth of HPT and γ-TMT transgenics was not significantly different from wild type on control plates and on plates supplemented with up to 200 mm sorbitol or sodium chloride, except for a 25% growth retardation of HPT knockdown plants on 200 mm NaCl (Tables III and IV; see Figs. 4, A–C and 5, A–C for the corresponding phenotypes). Sorbitol and sodium chloride of equal or more than 300 mm provoked distinct phenotypes for HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi tobacco (Figs. 4, A–C and 5, A–C for lines StHPT:RNAi-28 and Stγ-TMT:RNAi-55; see Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2 for the performance of lines StHPT:RNAi-49 and Stγ-TMT:RNAi-82 challenged with sorbitol and NaCl, respectively).

Table III.

Biomass of wild-type and transgenic lines grown on medium supplemented with different concentrations of sorbitol

Wild-type (WT), γ-TMT:RNAi-55, and HPT:RNAi-28 tobacco plants were treated with the sorbitol and NaCl concentrations indicated. Four weeks after the onset of sorbitol and NaCl stress, biomass production from stressed plants was determined. The depicted data are the means and sds of four independent measurements. **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.01. Significantly different values for identical treatments were classified into groups a and b, as indicated by the respective letter.

| Sorbitol | Wild Type | γ-TMT:RNAi-55 | HPT:RNAi-28 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mg Fresh Weight | mg Fresh Weight | % Wild Type | mg Fresh Weight | % Wild Type |

| 0 | 1.76 ± 0.38a | 1.65 ± 0.36a | 93.8 ± 20.6 | 1.47 ± 0.27a | 83.6 ± 15.2 |

| 100 | 1.38 ± 0.15a | 1.36 ± 0.11a | 98.5 ± 8.43 | 1.22 ± 0.11a | 88.6 ± 8.21 |

| 200 | 0.84 ± 0.08a | 0.97 ± 0.10a | 115.5 ± 12.8 | 0.77 ± 0.09a | 91.5 ± 11.1 |

| 300 | 0.22 ± 0.08a | 0.64 ± 0.17b** | 262.5 ± 65.1 | 0.21 ± 0.07a | 93.6 ± 34.6 |

| 400 | 0.17 ± 0.07a | 0.42 ± 0.05b*** | 224.2 ± 23.7 | 0.13 ± 0.04a | 78.2 ± 26.1 |

Table IV.

Biomass of wild-type and transgenic lines grown on medium supplemented with different concentrations of NaCl

Wild-type (WT), γ-TMT:RNAi-55, and HPT:RNAi-28 tobacco plants were treated with the sorbitol and NaCl concentrations indicated. Four weeks after the onset of sorbitol and NaCl stress, biomass production from stressed plants was determined. The depicted data are the means and sds of four independent measurements. *, P < 0.10; **, P < 0.05; and ***, P < 0.01. Significantly different values for identical treatments were classified into groups a and b, as indicated by the respective letter.

| NaCl | Wild Type | γ-TMT:RNAi-55 | HPT:RNAi-28 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mg Fresh Weight | mg Fresh Weight | % Wild Type | mg Fresh Weight | % Wild Type |

| 0 | 1.61 ± 0.16a | 1.48 ± 0.30a | 92.1 ± 19.1 | 1.42 ± 0.29a | 91.1 ± 18.9 |

| 100 | 1.38 ± 0.10a | 1.29 ± 0.12a | 93.2 ± 8.87 | 1.25 ± 0.13a | 92.7 ± 9.4 |

| 200 | 1.03 ± 0.11a | 0.87 ± 0.08ab | 84.5 ± 8.55 | 0.71 ± 0.06b** | 73.9 ± 8.6 |

| 300 | 0.92 ± 0.17a | 0.68 ± 0.09b* | 73.8 ± 14.2 | 0.56 ± 0.06b*** | 60.8 ± 7.1 |

| 400 | 0.58 ± 0.11a | 0.38 ± 0.08b* | 64.6 ± 15.2 | 0.34 ± 0.06b** | 63.3 ± 13.7 |

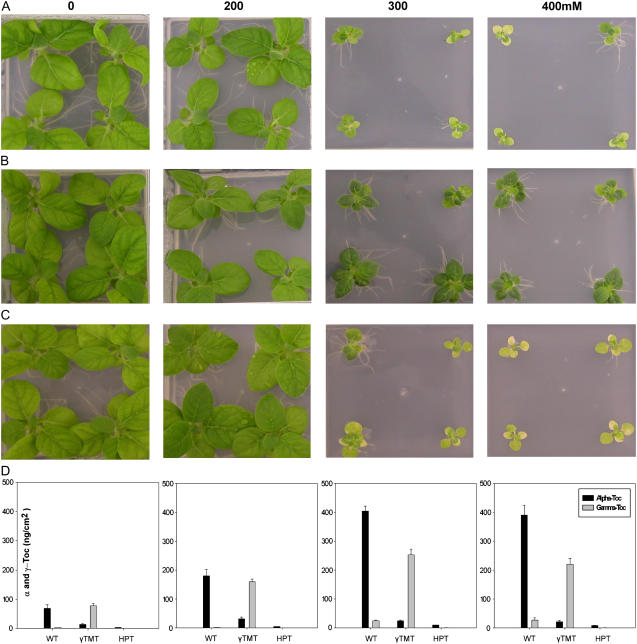

Figure 4.

Sorbitol-induced osmotic stress in wild-type tobacco and tobacco lines silenced for HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi. Two-week-old seedlings of Samsun NN, wild type (A), γ-TMT:RNAi-55 (B), and HPT:RNAi-28 (C) tobacco seedlings were subjected to Murashige and Skoog medium containing different amounts of sorbitol (0, 200, 300, and 400 mm, from left to right). Pictures of five representative individuals were taken after 4 weeks of sorbitol stress. D, Tocopherol composition in leaves of the wild-type and transgenic tobacco plants shown in A to C after 4 weeks of sorbitol stress of the concentration indicated above the columns. The depicted results are from a single representative experiment with four replicate samples ± sd.

Figure 5.

Salt-induced stress in HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi transgenic and wild-type tobacco plants. Samsun NN, wild type (A), γ-TMT:RNAi-55 (B), and HPT:RNAi-28 (C) tobacco seedlings were subjected to Murashige and Skoog medium containing different amounts of NaCl. The phenotype of five representative individuals after 4 weeks of salt stress is shown for every treatment, with 0, 200, 300, and 400 mm NaCl given in columns from left to right. D, Tocopherol composition in leaves of the wild-type and transgenic tobacco plants shown in A to C after 4 weeks of salt stress of the concentration indicated above the columns. The depicted results are from a single representative experiment with four replicate samples ± sd.

Silencing of HPT did not alter the response toward sorbitol significantly (Table III), while the HPT transgenics were more susceptible to salt stress than the wild type, exhibiting only 63% of wild-type fresh weight on 400 mm NaCl (Table IV). Leaves of HPT:RNAi plants were almost entirely chlorotic on 300 mm sodium chloride, while the wild type showed chlorosis on 400 mm NaCl only (compare Fig. 5, A and C; see Supplemental Fig. S2).

As in HPT:RNAi tobacco, silencing of γ-TMT also aggravated the sensitivity of the transgenics toward salt stress: this effect was less dramatic than for the HPT knockdown plants at 300 mm NaCl, but similar at 400 mm sodium chloride (Table IV; Fig. 5, A and B; Supplemental Fig. S2). Surprisingly, silencing of γ-TMT led to a substantial growth benefit of more than 2-fold over the wild type in osmotic stress of 300 and 400 mm sorbitol (Table III). Despite a decrease in growth of 75% on 400 mm sorbitol compared to the control plates without osmolyte, γ-TMT transgenics remained virescent at 400 mm sorbitol, even while wild-type and HPT:RNAi plants exhibited advanced chlorosis (Fig. 4, A–C; Supplemental Fig. S1).

Foliar Tocopherol Pools Exhibit Distinct Responses to Sorbitol and Salt Stress in the Tobacco Transgenics

It is well documented that the amount of tocopherol increases during stress (e.g. Collakova and DellaPenna, 2003; Havaux et al., 2005; Kanwischer et al., 2005; Maeda et al., 2006). Therefore, we examined how the disturbances in tocopherol biosynthesis in HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi affected tocopherol accumulation in the studied stress conditions. To this end, tocopherol contents in stress-acclimated leaves were determined after 4 weeks of osmotic and salt stress.

The wild-type Samsun NN displayed a more than 4-fold increase in total tocopherol from around 70 ng cm2 in controls to about 400 ng cm2 at 400 mm sorbitol or NaCl (Figs. 4D and 5D). The total tocopherol content correlated directly with the concentration of sorbitol and sodium chloride in the medium, with α-tocopherol contributing to more than 90% of the tocopherol pool in any condition in the wild type.

The total tocopherol content in unchallenged γ-TMT:RNAi plants was comparable to wild type, between 60 to 80 to ng cm2 (see Figs. 4D and 5D), except that γ- substituted α-tocopherol in the γ-TMT transgenics. Likewise, the α-tocopherol-deficient γ-TMT:RNAi transgenic tobacco plants accumulated similar amounts of γ-tocopherol instead of α-tocopherol during osmotic and salt stress (Figs. 4D and 5D), which was up to 350 ng cm2 γ-tocopherol. Compared to unstressed wild type, this would determine a 70-fold increase in γ-tocopherol. In conclusion, however, tocopherol biosynthesis got induced to a similar extent in γ-TMT:RNAi and in wild-type tobacco, resulting in the accumulation of γ- and α-tocopherol, respectively.

In contrast, silencing of HPT abrogated the capacity for tocopherol biosynthesis in the transgenics, so that the applied stress conditions did not result in significant tocopherol abundance. Nevertheless, total tocopherol content was induced from 1.6 (i.e. 2% of unstressed wild type) to 9.8 ng cm2 (i.e. 12% of unstressed and 1% of stressed wild type, respectively) after 4 weeks of either osmotic or salt stress in the HPT transgenics (Figs. 4D and 5D).

Pigment Analysis of Tobacco Transgenics and Wild-Type Plants Subjected to Sorbitol and Salt Stress

Tocopherols are involved in protecting lipids and the photosynthetic apparatus against oxidative damage together with the antioxidants ascorbate, glutathione, and the photosystem-associated xanthophyll cycle (Porfirova et al., 2002; Sattler et al., 2004; Foyer and Noctor, 2005; Havaux et al., 2005; Kanwischer et al., 2005). Therefore, we studied how chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were affected in the transgenic tobacco plants under osmotic and salt stress.

In control and low stress conditions (100 and 200 mm sorbitol or salt) there were no significant differences in chlorophyll and carotenoid content of wild type and both transgenic plants (Fig. 6, A, C, E, and F). In contrast, chromophore contents in wild type and transgenics were diminished whenever a chlorotic phenotype appeared, paralleling the observations described in Figures 4, A to C and 5, A to C and Supplemental Figures S1 and S2. Compared to the controls, chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were substantially decreased by about 25% each in HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi leaves at sodium chloride concentrations of 300 mm and higher, while the wild type showed a 30% reduction in pigments only on 400 mm NaCl (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Total tocopherol, ascorbate, dedydroascorbate, chlorophyll, and carotenoid contents in wild-type and transgenic tobacco leaves subjected to NaCl and sorbitol stress. Tobacco seedlings of wild-type Samsun NN (left bracket), γ-TMT:RNAi-55 (middle bracket), and HPT:RNAi-28 (right bracket) were subjected to oxidative and osmotic stress by supplementing 0 to 400 mm salt (A–C) or sorbitol (D–F) in 100 mm increments to the Murashige and Skoog culture medium. The numbers below the diagrams indicate the following conditions: 1, 0 mm; 2, 100 mm; 3, 200 mm; 4, 300 mm; 5, 400 mm of sodium chloride (A–C) or sorbitol (D–F). A and D, Total carotenoid (black bars) and total tocopherol contents (gray bars). B and E, Dehydroascorbate (black bars) and total ascorbate contents (gray bars). C and F, Chlorophyll contents (chlorophyll a, black bars; chlorophyll b, gray bars) were assessed in leaves after 4 weeks of stress. Total tocopherol was measured by HPLC (A and D), while chlorophyll (C and F), carotenoid (A and D), total ascorbate, and dehydroascorbate (DHA) were determined spectrophotometrically. The data shown are means from five replicate samples ± sd from one representative experiment. For ascorbate, significantly different values for identical treatments were classified into groups a and b, as indicated by the respective letter above the bar.

A decline in chromophore contents was also determined for wild type and HPT transgenics on 400 mm sorbitol (Fig. 6), while chlorophyll and carotenoid pools in γ-TMT:RNAi plants remained constant irrespective of the sorbitol concentration in the medium (Fig. 6, D and E). Interestingly, the chlorophyll a/b ratio decreased from 2.4 on control plates to approximately 1 for both wild type and HPT:RNAi transgenics on 400 mm sorbitol, due to a strong decline in chlorophyll a, but not b (Fig. 6F). This suggests that the photosystem core and accessory complexes become more damaged under osmotic stress than antenna complexes, which are rich in chlorophyll b.

Altering Tocopherol Composition and Quality by Silencing HPT and γ-TMT Does Not Lead to Strong Effects on the Ascorbate Pool in Response to Salt and Osmotic Stress

The ascorbate pool size is reportedly increased in response to oxidative stress (Noctor and Foyer, 1998) and there is strong experimental evidence that ascorbate constitutes the interface of the lipophilic tocopherols to the hydrophilic antioxidant network represented by the ascorbate-glutathione cycle (as summarized in Munné-Bosch and Alegre, 2002; Foyer and Noctor, 2005). However, it is unclear whether the ascorbate pool gets induced in the tocopherol-deficient Arabidopsis vte1 mutant, as contrasting results have been obtained (Havaux et al., 2005; Kanwischer et al., 2005).

After 4 weeks of treatment, total ascorbate contents increased in the wild-type Samsun NN with increasing amounts of sorbitol and salt (Fig. 6, B and E). Salt treatment effectuated a more pronounced increase of the ascorbate pool than sorbitol at identical concentrations (compare Figs. 7, B and E), e.g. 11.7 nmol cm−2 ascorbate on 400 mm NaCl compared to 7.4 nmol cm−2 ascorbate on 400 mm sorbitol.

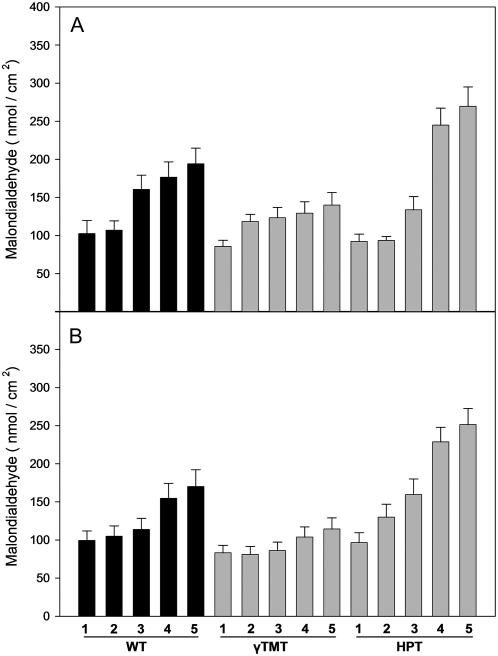

Figure 7.

Lipid peroxidation in leaves from HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi and wild-type tobacco plants after 4 weeks of osmotic and salt stress. Wild-type Samsun NN (WT, left bracket, black bars), γ-TMT:RNAi-55 (middle bracket, gray bars), and HPT:RNAi-28 (right bracket, gray bars) tobacco plants were treated with varying amounts between 0 and 400 mm of sodium chloride (top section) or sorbitol (bottom section). The numbers below the diagrams indicate the following conditions: 1, 0 mm; 2, 100 mm; 3, 200 mm; 4, 300 mm; 5, 400 mm of NaCl (A) or sorbitol (B). Lipid peroxidation was assayed from leaf samples after 4 weeks of stress by determining the amount of MDA. Data shown is the mean and sd of five independent measurements.

Unexpectedly, the ascorbate pool size in the HPT transgenics was similar to the wild type even in severe stress conditions (Fig. 6, B and E), although the progress of chlorosis in the transgenics was aggravated in salt stress (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S2).

Silencing of γ-TMT resulted in 30% less accumulation of ascorbate than in the wild type during salt and osmotic stress of equal or more than 200 mm sodium chloride or sorbitol, respectively (Fig. 6). Consistently, γ-TMT transgenics produced more biomass and exhibited less chlorosis on sorbitol than the wild type (Table IV; Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S1). In contrast, knockdown of γ-TMT resulted in elevated susceptibility toward salt (Table III; Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S2), while no substantial effect on the ascorbate pool was evident in salt-stressed γ-TMT transgenics compared to wild type.

In general, the oxidation state of the ascorbate pool was comparable for the three genotypes in all tested conditions (Fig. 6, B and E).

Lipid Peroxidation and Membrane Damage in Response to Oxidative Stress Are Increased by Silencing HPT and Decreased when γ-TMT Is Silenced

The observed increase in the pools of the antioxidants ascorbate and especially tocopherol under severe sorbitol and salt stress (Fig. 6) suggests that wild type and transgenics suffer from oxidative stress in both conditions. Malondialdehyde (MDA) occurs as a soluble side product during lipid peroxidation and has proven to be a reliable marker for oxidative stress (Müller-Moulé et al., 2003; Baroli et al., 2004). Excess lipid oxidation will eventually result in membrane damage. The extent of membrane damage can be quantified by ion leakage from the symplast (Rizhsky et al., 2002). Unfortunately, determining ion leakage from salt-stressed plants is prone to artifacts due to the elevated ion concentrations, so that only data for sorbitol stress were recorded.

Four weeks after the onset of salt or sorbitol stress, lipid peroxidation in wild type and both transgenics was correlated in a near-linear manner with increasing salt and sorbitol stress (Fig. 7). Lipid peroxidation in the γ-TMT transgenics was significantly lowered compared to wild type in either salt or sorbitol of equal or more than 200 mm (Fig. 7). This is in good accordance with the decreased accumulation of ascorbate observed in γ-TMT:RNAi leaves in both salt and sorbitol stress (Fig. 6, B and E). Together, this points toward a diminished oxidative stress in challenged γ-TMT:RNAi leaves, even though chlorosis is increased under salt stress compared to wild type (Fig. 5).

However, ion leakage from γ-TMT:RNAi and wild-type leaves was similar over a broad range of stress conditions (Table V). On 400 mm sorbitol, ion leakage remained comparable to lower sorbitol concentrations in γ-TMT knockdowns, while the wild type displayed a 2-fold increase compared to the transgenics (Table V).

Table V.

Membrane damage is induced by osmotic stress in wild-type and transgenic tobacco plants

Wild-type (WT), γ-TMT:RNAi-55, and HPT:RNAi-28 tobacco plants were cultivated on increasing concentrations of sorbitol as indicated on the left. Four weeks after the onset of osmotic stress, membrane damage was assayed from stressed plants by determining ion leakage from leaf discs. Data shown are the means and sds of four independent measurements. *, P < 0.10; **, P < 0.05; and ***, P < 0.01. Significantly different values for identical treatments were classified into groups a and b, as indicated by the respective letter.

| Sorbitol | WT % of Ion Leakage | γ-TMT % of Ion Leakage | HPT % of Ion Leakage |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm | |||

| 0 | 44.66 ± 3.09a | 47.49 ± 3.69a | 55.48 ± 5.06b* |

| 100 | 39.15 ± 2.96a | 46.31 ± 3.12a | 63.46 ± 9.76b** |

| 200 | 39.38 ± 7.70a | 47.39 ± 4.41ab | 55.25 ± 9.56b** |

| 300 | 47.85 ± 1.71a | 43.71 ± 6.86a | 61.41 ± 9.08b |

| 400 | 78.91 ± 0.81a | 48.80 ± 8.45b*** | 79.85 ± 8.39a |

In contrast to the γ-TMT transgenics, MDA content was significantly elevated in HPT-silenced plants above 100 mm salt or sorbitol compared to the wild type (Fig. 7). At 400 mm of either stressor, HPT:RNAi tobacco accumulates 1.5-fold more MDA than the wild type (Fig. 7). In addition, ion leakage was already increased by 25% in HPT:RNAi leaves in the absence of sorbitol or sodium chloride supplements on control plates (Table V). Ion leakage in the HPT transgenics reached similar values than in the wild type when 400 mm sorbitol was supplied.

To evaluate whether a substitution of α- for γ-tocopherol in γ-TMT:RNAi plants improved the resilience of the transgenics toward oxidative stress in a less artificial system, we sprayed leaves of soil-grown plants with different amounts of methyl viologen (Fig. 8). With the methyl viologen treatments, we aimed to specifically impose oxidative stress on chloroplasts, mimicking the scenario in chloroplasts of sorbitol-stressed leaves. Ion leakage from wild-type leaves correlated with the amount of applied methyl viologen, rising from 20% in the controls to 85% when 50 μm methyl viologen had been sprayed (Fig. 8). With the exception of the untreated control leaves, ion leakage in HPT knockdown lines was similar to the wild type. As in the in vitro experiment, untreated HPT:RNAi leaves displayed elevated ion leakage in the controls relative to the wild type (compare Fig. 8 and Table V).

Figure 8.

Ion leakage in wild-type and transgenic tobacco leaves after methyl viologen treatment. Fully expanded source leaves of 8-week-old tobacco plants of wild-type Samsun NN (left bracket, black bars), γ-TMT:RNAi-55 (middle bracket, gray bars), and HPT:RNAi-28 (right bracket, gray bars) were sprayed with 1 mL of the indicated methyl viologen solution on 2 d prior to the harvest of leaf disc samples. The numbers given behind the genotype acronym at the bottom indicate the following conditions: 0, 0 μm; 5, 5 μm; 20, 20 μm; 50, 50 μm methyl viologen. Ion leakage is given in percent of maximum leakage after boiling. The data shown are means from five replicate samples ± sd from one representative experiment.

Also paralleling the observations from sorbitol-stressed plantlets, leaves of γ-TMT transgenics exhibited a 35% lower ion leakage than the wild type in the concentration range of 5 to 20 μm methyl viologen (Fig. 8). When 50 μm methyl viologen was applied, the ion leakage from γ-TMT:RNAi leaves was not significantly different from the other two genotypes. However, membrane damage got already saturated in the wild-type and HPT:RNAi plants after spraying 20 μm methyl viologen (Fig. 8), indicating that 50 μm methyl viologen might be too harsh to be overcome by the antioxidant system.

Taken together, our results indicate that a lack of tocopherols in HPT:RNAi decreases membrane integrity in the absence of stress and exacerbates lipid oxidation in mild stress conditions already, while lipid peroxidation is diminished and membrane integrity is elevated in the γ-TMT transgenics during oxidative stress caused by either sorbitol or methyl viologen.

Silencing of HPT and γ-TMT Alters Sugar and Amino Acid Metabolism in Stress Conditions

Severely tocopherol-deficient maize (Zea mays) and potato plants are reportedly compromised in sugar export and accumulate soluble sugars and starch, paralleled by the formation of callose plugs at the plasmodesmata (Provencher et al., 2001; Hofius et al., 2004). The Arabidopsis HPT mutant vte2 displayed this phenomenology only upon chilling (Maeda et al., 2006). Carbon and nitrogen metabolism interdepend on each other (see Fritz et al., 2006 for a very recent report and the refs. cited therein). In an oversimplified view, carbon availability triggers nitrogen metabolism (e.g. Henkes et al., 2001; Matt et al., 2001; Gibon et al., 2004), and vice versa, nitrogen availability modulates carbon flow in the leaf (e.g. Scheible et al., 1997; Geiger et al., 1999). Therefore, we assessed how sugar and amino acid metabolism are affected in the HPT and γ-TMT-silenced tobacco plants during salt and sorbitol stress.

Salt and sorbitol stress provoked clearly distinct responses in sugar metabolism in the wild type, although 300 mm of both salt and sorbitol provoked an accumulation of starch and soluble sugars (Fig. 9, A–J). Compared to unsupplemented plates, starch accumulated 3- and 20-fold in wild type on 300 mm sorbitol and salt, respectively, with salt being about 5 times more potent than sorbitol (compare Fig. 9, D–J); less than 300 mm of either stressor did not result in a considerable accumulation of starch. The accumulation of soluble sugars in the wild type was found to correlate directly with salt and sorbitol concentrations. The monosaccharides Glc and Fru accounted for the increase in total soluble sugar content with increasing sorbitol stress (Fig. 9, G–I), while Suc accumulation correlated with increasing salt stress (Fig. 9, A–C). Glc and Fru contents were finally increased about 20-fold on 300 mm sorbitol compared to the controls, while Suc was found to accumulate more than 10-fold on 300 mm sodium chloride.

Figure 9.

Carbohydrate and amino acid contents in leaves from HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi and wild-type tobacco plants after 4 weeks of salt and sorbitol stress. Wild-type Samsun NN (WT, left bracket), γ-TMT:RNAi-55 (middle bracket), and HPT:RNAi-28 (right bracket) tobacco plants were treated with varying amounts between 0 and 300 mm of sodium chloride (left column) or sorbitol (right column). The numbers below the diagrams indicate the following conditions: 1, 0 mm; 2, 100 mm; 3, 200 mm; 4, 300 mm of either NaCl (left) or sorbitol (right). The contents of the soluble sugars Glc (A and G), Fru (B and H), and Suc (C and I), of starch (D and J), the compatible solute Pro (E and K), and total amino acids (F and L) were assayed from leaf samples after 4 weeks of stress. The depicted data are mean and sd of five independent measurements from one representative experiment.

The γ-TMT transgenics displayed comparable steady-state pools of soluble sugars as the wild type, with the remarkable exception that Glc and Fru accumulation were 2-fold lower in sorbitol stress of 200 mm or higher compared to wild type (Fig. 9, G and H).

Abrogating HPT activity in HPT:RNAi abolished the correlation of sugar or starch accumulation with the degree of salt or sorbitol stress. Sugar and starch pools in the HPT transgenics did not respond to salt stress at all (Fig. 9D); soluble sugar contents in HPT:RNAi leaves were already substantially elevated compared to wild type or γ-TMT:RNAi lines in low NaCl (Fig. 9, A–C), with starch contents in the HPT transgenics being as high as in wild type or γ-TMT transgenics grown on 300 mm sorbitol (Fig. 9, D and J). In sorbitol stress, up to 200 mm sorbitol, starch, and soluble sugar contents in HPT transgenics remained comparable to untreated wild type on control plates (Fig. 9, G–J). In contrast, HPT:RNAi leaves accumulated 30% more Suc, 75% more Glc, and 100% more Fru than wild type or γ-TMT on 300 mm sorbitol, while starch contents rose to similar levels as in the two other genotypes. In contrast to maize sxd1, Arabidopsis vte2, and TC-silenced potato plants, we failed to observe a sugar export block in the tocopherol depleted HPT transgenics in any of the tested conditions, which would involve much stronger accumulation of starch and Suc. Attempts to probe plasmodesmatal obstruction in HPT transgenics remained inconclusive (data not shown).

Characteristic changes in the composition of the free amino acid pool coincided with the accumulation of starch or soluble sugars (Supplemental Fig. S3). The compatible solute Pro accumulated 15- and 20-fold on 300 mm sorbitol and NaCl compared to the unsupplemented controls in all genotypes (Fig. 9, K and E, respectively), as did its precursor Glu in salt stress (see Supplemental Fig. S3). Proline accounted for 40% to 50% of the free amino acid pool when 300 mm of either salt or sorbitol were supplied (compare values in Fig. 9, E and F, or Fig. 9, K and L). It is noteworthy that a 9-fold accumulation of Pro could be observed when as little as 100 mm sodium chloride were supplied, while 200 mm sorbitol led to a 4-fold Pro accumulation only (compare Fig. 9, E and K).

Apart from this indicative amino acid, we also observed correlations between the accumulation of Asn, Gln, His, most branched-chain, aromatic amino acids and hexose contents with increasing sorbitol stress (Supplemental Fig. S3). Almost the same subset of amino acids accumulated 4- to 9-fold in the wild type on 400 mm NaCl, while the transgenics did not accumulate these amino acids (Supplemental Fig. S3). In general, the transgenics did not show pronounced differences in free amino acid contents to the wild type in sorbitol stress, with γ-TMT:RNAi plants being indistinguishable from the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

Salt and Sorbitol Stress Have Different Targets in Cellular Metabolism and Induce Characteristic Physiological Responses

The rationale behind employing salt and sorbitol stress in our study was to elicit specific stress patterns. Both severe salt and sorbitol stress finally result in oxidative stress caused by hyperosmolarity (as reviewed by Wang et al., 2003). However, salt and sorbitol stress will primarily target different subcellular compartments. Excess symplastic salt concentrations endanger protein integrity and therefore, have to be sequestered in the vacuole or extruded from the cells, concomitantly disturbing pH and ion homeostasis across the tonoplast and the plasma membrane (Serrano and Rodriguez-Navarro, 2001). Increased salt tolerance was achieved by generating transgenic plants overexpressing the plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 (Shi et al., 2003) or the vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter AtNHX1 (Apse et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2001; Zhang and Blumwald, 2001), demonstrating that the sequestration capacity for sodium is limiting in high salinity. Our data on carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism provide evidence that the assumed mode of sodium chloride toxicity also holds true for our experimental setup: in transgenics and the wild type, we observed a 9-fold accumulation of Pro (and its precursor Glu) in 100 mm salt stress (Fig. 9; Supplemental Fig. S3), while Pro biosynthesis, evidenced by steady-state contents of itself and its precursor Glu, was not induced in 100 mm sorbitol stress, indicating that the constraint to protect macromolecules with the accumulation of compatible solutes is more specific for salinity. Furthermore, a high salinity of 400 mm NaCl led to a dramatic accumulation of starch and Suc as well as Asp and pyruvate-derived amino acids in the wild type (Fig. 9; Supplemental Fig. S3), indicating a severely disturbed central cellular metabolism. Likewise, this was not observed in sorbitol stress. The correlation of Suc and starch accumulation with increasing salt stress also argues for a progressing sugar export block from source leaves in response to poisoning by salinity, as commonly observed under various stress conditions (e.g. Voll et al., 2003; Sam et al., 2004; Maeda et al., 2006).

In contrast to sodium chloride, sorbitol is a compatible solute, which does not interfere with enzymatic activities in plasmatic compartments. Sorbitol would more specifically cause desiccation of the cells in addition to hyperosmotic stress. In the second line, reduced water availability would finally increase oxidative stress in the chloroplasts by stimulating the generation of ROS and, concomitantly, lipid peroxy radicals in illuminated thylakoids. Paralleling the increased tolerance toward sorbitol stress, the γ-TMT transgenics were less susceptible than wild type toward the electron donor methyl viologen that specifically induces oxidative stress in the thylakoids by stimulating the generation of superoxide anions at PSI reaction centers (Fig. 8). Taken together, this indicates that γ-tocopherol in γ-TMT:RNAi leaves is capable of mitigating ROS-induced stress in chloroplasts better than α-tocopherol in wild-type leaves. Increasing ROS quenching capacity by, for example, overexpression of superoxide dismutase (Gupta et al., 1993) or glutathione S-transferase and glutathione peroxidase (Roxas et al., 1997), has already been shown to possess the potential to alleviate oxidative stress.

In support of our model of sorbitol action, we noted an enhanced hexose accumulation in wild type and γ-TMT:RNAi under sorbitol stress compared to salt stress (Fig. 9), indicating a rearrangement of carbohydrates in favor of osmotically competent monosaccharides like Glc and Fru. The compatible solute Pro accumulated in elevated sorbitol stress of more than 300 mm only (Fig. 9). As concluded from the metabolic analysis, the specific accumulation of soluble sugars indicates that desiccation predominates over sorbitol toxicity and oxidative stress in sorbitol treatments. An accumulation of hexoses during drought (i.e. desiccation) stress has already been described for tobacco (e.g. Karakas et al., 1997) and was also observed for barley (Hordeum vulgare) leaves (Villadsen et al., 2005) and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) suspension cells (Wang et al., 1999) subjected to drought and osmotic stress. Mostly, drought stress was accompanied by a decrease in starch biosynthesis in favor of soluble sugars (Karakas et al., 1997; Villadsen et al., 2005).

Tocopherol Depletion by Silencing HPT Decreases Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Tobacco

HPT catalyzes the committed prenyl transferase step in tocopherol biosynthesis at the branch point of tocopherol and tocotrienol biosynthesis (Fig. 1). By posttranscriptional silencing of HPT activity, we could obtain transgenic tobacco with less than 2% of wild-type foliar tocopherol content. Although tobacco seeds are capable to synthesize tocotrienols (Falk et al., 2003), wild-type tobacco leaves are devoid of tocotrienols (Cahoon et al., 2003; Rippert et al., 2004). Even in severe stress, we could only detect traces of tocochromanols in HPT:RNAi leaves (data not shown), so that it can be ruled out that the depletion of tocopherols in HPT knockdown tobacco is functionally compensated by tocotrienols.

As expected, HPT:RNAi leaves displayed an increased sensitivity toward salt and sorbitol stress, although membrane damage and lipid peroxidation were already elevated in unstressed HPT transgenics (Table V). Sorbitol stress, despite some minor changes in carbon and nitrogen metabolism, rather specifically affected lipid peroxidation in HPT transgenics compared to the two other genotypes (Fig. 7). In contrast, the extent of lipid peroxidation, pigment breakdown, and the changes in carbon and nitrogen metabolism were aggravated in the HPT transgenics compared to the wild type in salt stress (Tables III–V; Figs. 6, 7, and 9; Supplemental Fig. S3). Aside from a direct impact of elevated lipid peroxidation, the increased susceptibility of HPT:RNAi tobacco toward oxidative stress caused by salt and (to a lesser extent) sorbitol might be facilitated by enhanced ROS signaling in the transgenics early in the acclimation process. Transcriptome analysis of unchallenged Arabidopsis vte2 seedlings revealed that the increased lipid peroxidation in this HPT mutant triggered ROS-regulated genes, as during pathogen challenge or oxidative stress-like ozone (Sattler et al., 2006). Interestingly, the induced genes in vte2 seedlings were not positively regulated by methyl jasmonate (Sattler et al., 2006), the synthesis of which is elevated when lipid peroxidation occurs. In contrast, Arabidopsis TC mutants (vte1) challenged with low temperature and high light exhibited a transient increase in methyl jasmonate (Munné-Bosch et al., 2007). However, the diverging results obtained for vte1 and vte2 could be explained by the different age of the examined plants or by the accumulation of the tocopherol precursor 2,3-dimethyl-5-phytyl-1,4-benzoquinone in vte1 (Sattler et al., 2003), which is absent in vte2.

Despite the evidence that Arabidopsis vte2 mutants exhibit an enhanced ROS response (Sattler et al., 2006), the soluble antioxidants ascorbate and glutathione were not substantially induced in the Arabidopsis tocopherol-deficient vte1 and vte2 mutants (Havaux et al., 2005; Kanwischer et al., 2005). We also found that the ascorbate pool was not significantly increased in tocopherol-deficient HPT knockdown tobacco compared to wild type (Fig. 6). But as tocopherols connect the lipophilic xanthophyll cycle to the soluble antioxidant network governed by the ascorbate-glutathione cycle (Foyer and Noctor, 2003), high light sensitivity of vte1 was greatly enhanced when other antioxidant systems like the zeaxanthin or the glutathione-ascorbate cycle were compromised concomitantly (Havaux et al., 2005; Kanwischer et al., 2005). This demonstrates compensatory capacity in the foliar antioxidant network, which might also account for the comparable response of the ascorbate pool in HPT transgenics and wild type during acclimation to the imposed oxidative and osmotic stress.

The Substitution of α- for γ-Tocopherol in γ-TMT-Silenced Tobacco Increases Osmotolerance

We achieved an almost quantitative substitution of α- for γ-tocopherol by silencing γ-TMT in tobacco with only 5% of foliar α-tocopherol left compared to wild type. To date, mutants with decreased γ-TMT activity have been isolated from Arabidopsis (vte4), sunflower (Helianthus annuus), and Synechocystis (slr0089) and all of them accumulate γ-tocopherol instead of α-tocopherol (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998; Bergmüller et al., 2003; Hass et al., 2006). Interestingly, the total tocopherol content in sunflower and Arabidopsis mutant leaves remained similar to the corresponding wild type (Bergmüller et al., 2003; Hass et al., 2006), while the Synechocystis mutant lacked α-tocopherol without any compensation in γ-tocopherol (Shintani and DellaPenna, 1998; Sakuragi et al., 2006). Among these γ-TMT mutants, only the Arabidopsis vte4 mutant was tested for abiotic stress tolerance and did not exhibit an altered stress response toward heat, cold, and high light compared to the wild type (Bergmüller et al., 2003). In contrast, we imposed sorbitol, methyl viologen, and sodium chloride to probe whether replacing α-tocopherol with γ-tocopherol affects oxidative stress tolerance in tobacco.

Silencing γ-TMT in tobacco, thereby exchanging α- for γ-tocopherol, resulted in an elevated susceptibility toward salt, but a diminished susceptibility toward osmotic stress and methyl viologen compared to the wild type (Tables III and IV; Figs. 4, 5, and 8). Ascorbate pool size and lipid peroxidation were reduced in the γ-TMT transgenics compared to the wild type in salt and sorbitol treatments (Fig. 7), indicating less oxidative stress in the transgenics in both stress conditions. As judged from carotenoid and chlorophyll contents (Fig. 6), the photosynthetic apparatus in γ-TMT transgenics remained intact in sorbitol, but not in NaCl stress. While the chlorophyll a to b ratio collapsed in wild-type leaves on 400 mm sorbitol, leaves of γ-TMT:RNAi plants retained the same ratio on 400 mm sorbitol as on control plates.

Our results shed new light on the in vivo function of γ-tocopherol, allowing two major conclusions. First, γ-tocopherol is more potent than α-tocopherol in conferring desiccation tolerance in vivo. This is presumably mediated by the higher in vivo lipid antioxidant activity of γ-tocopherol (that is present in the γ-TMT transgenics) compared to α-tocopherol (abundant in wild-type leaves). Consequently, lipid peroxidation is diminished, membrane damage is decreased, and pigment loss is reduced in the γ-TMT transgenics compared to wild type when oxidative stress arises during desiccation. This assumption is supported by two observations: (1) γ-TMT:RNAi plants exhibited less membrane damage after targeted oxidative stress was imposed on thylakoids (and the PUFAs contained therein) by stimulating ROS production with methyl viologen (Fig. 8); and (2) by the fact that γ-tocopherol is the naturally predominant tocopherol derivative in most oil-storing seeds (Fig. 1) and that loss of γ-tocopherol was shown to result in elevated PUFA oxidation and diminished seed longevity in Arabidopsis (Sattler et al., 2004). Likewise, we also observed a substantially decreased germination efficiency in the tocopherol depleted HPT transgenics (data not shown). Thus, the presence of γ-tocopherol is not only pivotal for seed desiccation tolerance, but can also increase desiccation tolerance in leaves.

In oil-storing seeds, storage lipids are located in oil bodies that reside in the cytosol. It was reported that tocochromanols are tightly associated with oil bodies from sunflower and oat (Avena sativa) seeds (Fisk et al., 2006; White et al., 2006). As excess lipid peroxidation does not occur in, for example, Arabidopsis wild type but in γ-tocopherol-deficient seeds (Sattler et al., 2004), it can be assumed that tocochromanol contents in oil bodies are sufficient to efficiently protect seed PUFAs from oxidation. For leaves, it has been demonstrated that tocopherols are abundant in plastoglobules and evidence is emerging that tocopherol biosynthesis also occurs in plastoglobules (Austin et al., 2006; Vidi et al., 2006). Plastoglobules are thylakoid protrusions composed of lipophilic constituents like triacylglycerols, quinones, chlorophyll, carotenoids, and also monogalactosyldiacylglycerol and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (Ghosh et al., 1994; Austin et al., 2006, and refs. therein) that increase in number during senescence and in oxidative stress (Steinmüller and Tevini, 1985; Munné-Bosch and Alegre, 2004) when chlorophyll turnover is high. Free phytol from chlorophyll breakdown might directly be salvaged for tocopherol biosynthesis (Ischebeck et al., 2006; Dörmann, 2007), which is required for antioxidant protection in these conditions.

As a second conclusion, γ-tocopherol cannot substitute α-tocopherol to ensure a better survival in salt stress, although markers for oxidative stress were decreased in the γ-TMT transgenics compared to wild type. Consequently, α-tocopherol appears to better mediate protection of macromolecules from denaturation by salt than γ-tocopherol. Alternatively, γ-tocopherol might not be able to influence cellular signaling like α-tocopherol does.

In this study, we have discovered that γ-tocopherol exerts a specific function in osmoprotection in vivo, providing evidence that α- and γ-tocopherol may not be functionally equivalent in many respects. Our results raise a wealth of new questions on the roles of individual tocopherol derivatives. Future aims will encompass attempts to discover the specific in vivo functions of α- and γ-tocopherol in ROS-mediated signaling and their specific antioxidant activities, using the tobacco lines silenced for HPT and γ-TMT as a tool.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv Samsun NN) plants were obtained from Vereinigte Saatzuchten and maintained in tissue culture under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark period (50 μE m−2 s−1 light, 21°C) at 50% relative humidity on Murashige and Skoog medium (Sigma) containing 2% (w/v) Suc.

Seeds of transgenic plants were sown on Murashige and Skoog medium containing kanamycin and after 14 d, the resistant seedlings were either transferred to Murashige and Skoog medium containing NaCl and sorbitol of the concentrations indicated in the figure legends (0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mm) or the kanamycin-resistant seedlings were transferred on soil and further cultivated in the greenhouse in a 16-h/8-h light/dark cycle at 24°C, a relative humidity of 50%, and a photon flux density of 150 μm m−2 s−1.

For methyl viologen treatments, the above selection procedure was modified. Seeds of transgenic lines were sown on Murashige and Skoog medium without kanamycin and 14 d after the transfer to soil, one mature leaf from each plant was harvested to determine its tocopherol content. Plantlets matching the tocopherol profile of the parental line were propagated and methyl viologen treatments were started when the plants were 8 weeks old. Two hours after the beginning of the light phase, 1 mL of 0 to 50 μm methyl viologen spray was applied on one fully expanded source leaf per plant on two consecutive days. Leaf discs from sprayed leaves were harvested 6 h after the second methyl viologen application and ion leakage was determined as described below.

Cloning of Partial HPT and γ-TMT cDNA Sequences from Potato, RNAi Vector Construction, and Tobacco Transformation

To obtain heterologous HPT and γ-TMT sequences for RNAi constructs, we identified partial expressed sequence tag (EST) clones for potato (Solanum tuberosum) HPT (accession no. BI919738) and potato γ-TMT (accession no. BQ116842) by homology search with tBLASTn (Altschul et al., 1990). A 650-bp fragment of the StHPT open reading frame containing nucleotides 51 to 701 of the potato HPT EST clone (accession no. BI919738) was amplified by reverse transcription-PCR using primers AA7 (5′-ggatccCTGATTTAGAAATCAAAAATGGAATC-3′) and AA8 (5′-gtcgacCCAACGATCCATCCAAGCCAAAAAC-3′), which introduced terminal BamHI and SalI recognition sites, respectively, into the sequence. To amplify a 625-bp fragment comprising nucleotides 31 to 659 of the Stγ-TMT open reading frame from the partial potato EST clone (accession no. BQ116842) by reverse transcription-PCR, primers AA9 (5′-ggatccGTTAAGAATCCTCTGCGAACAATAAA-3′) and AA10 (5′-gtcgacGGATTAGGGGATAAGGTTTCATTTCA-3′) were applied, also introducing terminal BamHI and SalI recognition sites.

The 650-bp fragment of the StHPT gene and 625-bp fragment of the Stγ-TMT gene were inserted in sense orientation downstream of the gibberellin (GA) 20-oxidase intron in the pUC-RNAi vector as described by Chen et al. (2003). The same fragments were subsequently placed in antisense orientation into the XhoI/BglII sites of pUC-RNAi already carrying the StHPT and Stγ-TMT sense fragments, respectively. Finally, the entire RNAi cassette comprising sense and antisense fragments of StHPT or Stγ-TMT interspersed by the GA 20-oxidase intron were excised from pUC-RNAi using the flanking PstI sites and inserted into the SbfI site of pBinAR (Höfgen and Willmitzer, 1990) between the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and ocs terminator, yielding the constructs pBin-StHPT-RNAi and pBin-Stγ-TMT-RNAi. Transformation of tobacco plants by using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1:pGV2260 was carried out as described previously (Rocha-Sosa et al., 1989).

Data Normalization

We found that specific leaf fresh and specific leaf dry weight increased to a similar extent with increasing sorbitol and salt concentrations in the medium in all genotypes; e.g. a dry weight increase of 2.3-fold (wild type), 2.5-fold (γ-TMT:RNAi), and 2.4-fold (HPT:RNAi) and a fresh weight increase of 1.7-fold (wild type) and 1.9-fold (both transgenics) was determined when plantlets grown on 300 mm NaCl were compared with plants from control plates.

Trying to find the best normalization of, for example, our lipid peroxidation (MDA) data, we realized that referring to fresh or dry weight would make lipid peroxidation seem declining with increasing salt and sorbitol, while the severity of oxidative stress is undoubtedly correlated with salt or sorbitol concentrations in the medium. Consequently, our results would have diverged from commonly observed responses in stressed leaves (e.g. Havaux et al., 2005; Golan et al., 2006).

PUFAs like 18:3 (in digalactosyldiacylglycerol) and 16:3 fatty acids (in monogalactosyldiacylglycerol) are highly enriched in thylakoid galactolipids (Dakhma et al., 1995; Ma and Browse, 2006). In drought-stressed leaves, an increase in fatty acid saturation has frequently been observed (e.g. in Dakhma et al., 1995). Likewise, we observed a shift in the composition of C18 fatty acids from 18:3 (54.7% of total in control versus 39.7% of total in stress conditions) to 18:2 fatty acids (4.2% of total in control versus 24.1% of total in stress conditions). The diminished 18:3 to 18:2 fatty acid ratio can be correlated with the decrease in chlorophyll and carotenoid contents (Fig. 6, A, C, D, and F), potentially reflecting diminished chloroplast number per leaf area and decreased chloroplast integrity during stress. In this respect, MDA normalization to leaf area accounted best for the stress-dependent decrease in total PUFAs. With the chosen normalization for our MDA measurements, the results for ion leakage (that is determined as a relative measure and not normalized) and MDA contents gave a coherent picture (compare Fig. 7 and Table V), supporting the validity of the chosen normalization.

Tocopherol Extraction and Measurement

Tocopherols were extracted basically as described for cereal seeds by Panfili et al. (2003), by grinding and homogenizing 25 mg of frozen leaf material in 500 μL 100% methanol. After 20 min of incubation at 30°C, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was transferred to new tubes, and the pellet was reextracted twice with 250 μL 100% methanol at 30°C for 30 min, pooling all supernatants.

The recovery for α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol from tobacco leaves was determined by resolving the methanol extracts on a phenomenex C18 reverse-phase column (250 mm length and 4.6 μm particle size) with an isocratic acetonitril:methanol (90:10, v/v) gradient for 40 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min on a Dionex Summit HPLC system. After each run, the column was rinsed for 10 min with acetonitril:methanol (10:90, v/v) and reequilibrated with the mobile phase for 5 min. Tocopherols were detected and quantified according to standards (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals) by fluorescence with excitation at 290 nm and emission at 325 nm. The recoveries for α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol from spiked tobacco leaf extracts were 90% ± 13%, 98% ± 21%, 95% ± 17%, and 99% ± 17%, respectively, as determined for at least four independent replicates. As we could not detect β-tocopherol in any given tobacco sample, we abstained from the separation of β- and γ-tocopherol with the above described method in favor of minimizing running time by modifying the gradient as follows.

The organic extracts were resolved on a phenomenex C18 reverse-phase column (250 mm length and 4.6 μm particle size) with an isocratic acetonitrile:methanol (50:50, v/v) mobile phase for 30 min at the same flow rate of 1 mL/min prior to rinsing and reequilibration of the column as stated above. Tocopherols were detected by fluorescence with excitation at 290 nm and emission at 325 nm. Tocopherols were identified by retention time and quantified relative to dilution series of tocopherol standards.

Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Determination

Chlorophyll and carotenoids were extracted from leaves with 95% ethanol and quantified by measuring the absorbances at 664, 648, and 470 nm as described by Lichtenthaler (1987).

Ion Leakage Measurement

Membrane damage was assayed by measuring ion leakage from leaf discs according to Rizhsky et al. (2002). For each measurement, six leaf discs (10 mm diameter) were floated abaxial side up on 8 mL of double distilled water for 20 h at 4°C. Following incubation, the conductivity of the bathing solution was measured with a conductivity meter (value A). The leaf discs were then returned to the bathing solution, introduced into sealed tubes, and incubated with the bathing solution at 95°C for 30 min. After cooling to room temperature the conductivity of the bathing solution was measured again (value B). For each measurement, ion leakage was expressed as percentage leakage, i.e. (value A/value B)·100.

Determination of Lipid Peroxidation

The level of lipid peroxidation in leaf tissues was determined in terms of the peroxidation byproduct MDA in the samples. Briefly, 50 to 100 mg leaf tissue was shock frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in 1 mL of 0.1% TCA. To the homogenized samples, 0.1 mL butylated hydroxytoluene (5 mg/mL) was added and the homogenates were incubated at 95°C for 30 min, centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 min, and 0.55 mL of the supernatant fraction was mixed with 0.55 mL of TBA solution (25% thiobarbituric acid). The mixture was heated at 95°C for 30 min, chilled on ice, and then centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 532 nm and corrected by subtracting nonspecific absorption at 600 nm. The amount of MDA was calculated according to an MDA standard curve.

Ascorbate Determination

Ascorbate contents were determined spectrophotometrically following a modified method of Law et al. (1983). Tobacco leaf discs (2 cm2) were ground in liquid N2 to a fine powder and samples were extracted with 1.1 mL 5% (w/v) 5-sulfosalicylic acid. After centrifugation the supernatant was diluted 1:1 with 150 mm NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.4) and stored on ice. The pH was adjusted to 5.5 to 6.5 using 10 n NaOH. For determination of reduced ascorbate, 200 μL of the extract was successively mixed with 100 μL double distilled water, 200 μL 10% (w/v) TCA, 200 μL 44% (v/v) H3PO4, 200 μL 4% (w/v) 2,2′-dipyridyl dissolved in 70% (v/v) ethanol, and 100 μL 3% (w/v) FeCl3. The mixtures were incubated for 60 min at 30°C and finally the color formation was measured at 525 nm. The ascorbate content was calculated using a standard curve measured with freshly prepared ascorbate standards.

For determination of total ascorbate, the neutralized extracts were oxidized by adding 50 μL dithiothreitol (10 mm) to the samples instead of distilled water. After 15 min incubation at room temperature, 50 μL 0.5% (w/v) N-ethylmaleimide were added followed by the same procedure as described above.

Determination of Soluble Sugars, Starch, and Free Amino Acids

Shock-frozen leaf samples were extracted in 80% ethanol and assayed for soluble sugars and starch as described by Voll et al. (2003) using a microtiter plate reader. For the determination of amino acid contents, primary and secondary amino acids were derivatized using the fluoropohore 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccimidyl carbamate (AccQ Taq) and separated at a flow rate of 1 mL/min at 37°C on a Dionex Summit HPLC system essentially as described by van Wandelen and Cohen (1997), using the eluents A (140 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.8; 7 mm triethanolamine), B (acetonitrile), and C (water) and fluorescence detection (excitation at 250 nm and detection at 395 nm).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical differences between wild-type and transgenic plants on different treatments were analyzed following the Duncan multiple range tests (Duncan, 1955). If significance levels are not specified, differences were considered significant at a probability level of P < 0.05.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers BI919738 and BQ116842.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Phenotype of additional HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi lines in sorbitol-induced osmotic stress.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phenotype of additional HPT:RNAi and γ-TMT:RNAi lines in salt stress.

Supplemental Figure S3. Free amino acid contents in leaves of transgenics and wild type after 4 weeks of salt and sorbitol stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Andrea Knospe (Institut für Pflanzengenetik und Kulturpflanzenforschung Gatersleben) for plant transformation and tissue culture work, the gardener team at Institut für Pflanzengenetik und Kulturpflanzenforschung Gatersleben, and Christine Hösl at the FAU Erlangen-Nuremberg for plant care.

This work was supported by the University of Teheran and the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology of the I.R. Iran (to A.-R.A.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Lars M. Voll (lvoll@biologie.uni-erlangen.de).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alscher RGEN, Heath LS (2002) Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J Exp Bot 53 1331–1341 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apse MP, Aharon GS, Snedden WA, Blumwald E (1999) Salt tolerance conferred by overexpression of a vacuolar Na+/ H+ antiporter in Arabidopsis. Science 285 1256–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin II Jr, Frost E, Vidi PA, Kessler F, Staehelin LA (2006) Plastoglobules are lipoprotein subcompartments of the chloroplast that are permanently coupled to thylakoid membranes and contain biosynthetic enzymes. Plant Cell 18 1693–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroli I, Gutman BL, Ledford HK, Shin JW, Chin BL, Havaux M, Niyogi KK (2004) Photo-oxidative stress in a xanthophyll-deficient mutant of Chlamydomonas. J Biol Chem 279 6337–6344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmüller E, Porfirova S, Dörmann P (2003) Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant deficient in γ-tocopherol methyltransferase. Plant Mol Biol 52 1181–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq M, Laurière C (2005) Osmotic signaling in plants: multiple pathways mediated by emerging kinase families. Plant Physiol 138 1185–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon EB, Hall SE, Ripp KG, Ganzke TS, Hitz WD, Coughlan SJ (2003) Metabolic redesign of vitamin E biosynthesis in plants for tocotrienol production and increased antioxidant content. Nat Biotechnol 21 1082–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Hofius D, Sonnewald U, Börnke F (2003) Temporal and spatial control of gene silencing in transgenic plants by inducible expression of double-stranded RNA. Plant J 36 731–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collakova E, DellaPenna D (2003) The role of homogentisate phytyltransferase and other tocopherol pathway enzymes in the regulation of tocopherol synthesis during abiotic stress. Plant Physiol 133 930–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakhma WS, Zarrouk M, Cherif A (1995) Effects of drought-stress on lipids in rape leaves. Phytochemistry 40 1383–1386 [Google Scholar]

- Dat JVS, Vranova E, Van Montagu M, Inzé D, Van Breusegem F (2000) Dual action of the active oxygen species during plant stress responses. Cell Mol Life Sci 57 779–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DellaPenna D, Last RL (2006) Progress in the dissection and manipulation of plant vitamin E biosynthesis. Physiol Plant 126 356–368 [Google Scholar]

- DellaPenna D, Pogson BJ (2006) Vitamin synthesis in plants: tocopherols and carotenoids. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57 711–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörmann P (2007) Functional diversity of tocochromanols in plants. Planta 225 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DB (1955) Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics 11 1–42 [Google Scholar]

- Falk J, Andersen G, Kernebeck B, Krupinska K (2003) Constitutive overexpression of barley 4-hydroxpheylpyruvate dioxygenase in tobacco results in elevation of the vitamin E content in seeds but not in leaves. FEBS Lett 540 35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk ID, White DA, Carvalho A, Gray DA (2006) Tocopherol: an intrinsic component of sunflower seed oil bodies. J Am Oil Chem Soc 83 341–344 [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G (2003) Redox sensing and signalling associated with reactive oxygen in chloroplasts, peroxisomes and mitochondria. Physiol Plant 119 355–364 [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G (2005) Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell 17 1866–1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Nakamura A, Tanaka Y (1999) Molecular cloning and expression of the Na+/ H+ exchanger gene in Oryza sativa. Biochim Biophys Acta 1446 149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz C, Palacios-Rojas N, Feil R, Stitt M (2006) Regulation of secondary metabolism by the carbon-nitrogen status in tobacco: nitrate inhibits large sectors of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant J 46 533–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaxiola RA, Rao R, Sherman A, Grisafi P, Alper SL, Fink GR (1999) The Arabidopsis thaliana proton transporters, AtNhx1 and Avp1, can function in cation detoxification in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 1480–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger M, Haake V, Ludewig F, Sonnewald U, Stitt M (1999) The nitrate and ammonium supply have a major influence on the response of photosynthesis, carbon metabolism, nitrogen metabolism and growth to elevated carbon dioxide in tobacco. Plant Cell Environ 22 1177–1199 [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Hudak KA, Dumbroff EB, Thompson JE (1994) Release of photosynthetic protein catabolites by blebbing from thylakoids. Plant Physiol 106 1547–1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Bläsing OE, Palacios N, Pankovic D, Hendriks JHM, Fisahn J, Höhne M, Günter M, Stitt M (2004) Adjustment of diurnal starch turnover to short days: depletion of sugar during the night leads to a temporary inhibition of carbohydrate utilization, accumulation of sugars and post-translational activation of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in the following night. Plant J 39 847–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan T, Müller-Moulé P, Niyogi KK (2006) Photoprotection mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana acclimate to high light by increasing photosynthesis and specific antioxidants. Plant Cell Environ 29 879–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusak MA, DellaPenna D (1999) Improving the nutrient composition of plants to enhance human nutrition and health. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50 133–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AS, Webb RP, Holaday AS, Allen RD (1993) Overexpression of superoxide dismutase protects plants from oxidative stress. Plant Physiol 103 1067–1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]