Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a metabolic regulator involved in maintaining glucose and fatty acid homeostasis. Besides its metabolic functions, the receptor has also been implicated in tumorigenesis. Ligands of PPARγ induce apoptosis in several types of tumor cells, leading to the proposal that these ligands may be used as antineoplastic agents. However, apoptosis induction requires high doses of ligands, suggesting the effect may not be receptor-dependent. In this report, we show that PPARγ is expressed in human primary T-cell lymphoma tissues and activation of PPARγ with low doses of ligands protects lymphoma cells from serum starvation-induced apoptosis. The prosurvival effect of PPARγ was linked to its actions on cellular metabolic activities. In serum-deprived cells, PPARγ attenuated the decline in ATP, reduced mitochondrial hyperpolarization, and limited the amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in favor of cell survival. Moreover, PPARγ regulated ROS through coordinated transcriptional control of a set of proteins and enzymes involved in ROS metabolism. Our study identified cell survival promotion as a novel activity of PPARγ. These findings highlight the need for further investigation into the role of PPARγ in cancer before widespread use of its agonists as anticancer therapeutics.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) belong to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. Like other members of this family, they serve as transcription factors and require ligands for activation. In a basal state, the receptors, in dimerization with retinoid X receptor (RXR), bind to promoter regions of their target genes. Ligand binding to PPARs releases corepressors bound to the receptor and recruits coactivators to initiate transcription of target genes. There are three subtypes of PPARs—α, β/δ, and γ—that differ in tissue distribution and ligand requirement. Among them, PPARγ is of particular interest because it plays a role in a variety of human pathological conditions, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and cancer.1,2

Most studies of PPARγ function focus on its role as a metabolic regulator. The receptor helps maintain lipid and glucose homeostasis in animals and humans.3,4 Whereas systemic knockout of PPARγ causes embryonic lethality,5,6 disruption of the receptor in insulin target tissues such as fat, liver, or skeletal muscle results in insulin resistance.7,8 Potential physiological ligands for PPARγ are lipophilic molecules that are derived from nutrition or metabolic pathways, including 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), polyunsaturated fatty acids and their oxidized forms, oxidized phospholipids, and triterpenoids. Thiazolidinediones (TZD, glitazones), potent synthetic ligands of PPARγ, are currently a mainstay therapy for type 2 diabetes. The drugs, by activating the receptor, increase tissue sensitivity to insulin and alleviate hyperglycemia. PPARγ regulates whole body lipid and glucose metabolism by its actions on the transcription of many metabolic genes at the cellular level. In adipose tissue, where it is most abundantly expressed, the receptor regulates genes of enzymes and transporters that increase uptake and reduce release of free fatty acid and glucose from cells to circulation.4

In addition to its role in metabolism, PPARγ has also been implicated in the development of cancer. Despite active research in the past few years, it remains debatable whether PPARγ is pro- or antineoplastic. PPARγ is highly expressed in several cancers, including carcinomas of the colon,9,10 breast,11 and prostate12 and liposarcoma.13 In addition, PAX8-PPARγ1 fusion has been identified in cases of human follicular thyroid carcinomas.14 Functionally, most of the in vitro and xenograft studies have shown that synthetic ligands of PPARγ inhibit proliferation and induce differentiation and apoptosis in tumor cells, suggesting that PPARγ is antineoplastic.15,16 However, in animals that are genetically predisposed to colon and mammary gland cancer, activation of PPARγ exacerbates tumor formation and growth.17–19 In humans, the receptor itself and several of its target genes are up-regulated in PAX8-PPARγ1-positive follicular thyroid carcinomas in comparison to the tumors lacking the fusion, demonstrating that increased PPARγ transcriptional activity contributes to carcinogenesis.20

It is unclear whether the observed in vitro effects of PPARγ ligands are mediated through the receptor or result from nonspecific activities of the drugs.16 To induce apoptosis of tumor cells, high concentrations of ligands are often required. In addition, antagonists that inhibit PPARγ’s activities also show antineoplastic properties by inducing apoptosis, suggesting that the effect may not act through the receptor.21,22 In a previous report, we found that PPARγ promotes survival under the condition of growth factor deprivation.23 Using cells containing or lacking PPARγ, we showed that the survival-enhancing effect occurs via a receptor-dependent mechanism. Furthermore, we demonstrated that PPARγ promotes cell survival by enhancing the ability of cells to maintain mitochondrial membrane potential.

Growth factor-independent survival is characteristic of tumor cells. Under normal conditions, growth factor withdrawal induces a series of metabolic changes leading to apoptotic cell death, such as decreased glucose uptake, impaired glycolysis, depolarization of mitochondrial potential, ATP depletion, hyperpolarization of mitochondrial inner membrane, matrix swelling, rupture of mitochondrial outer membrane, and release of cytochrome c and other proteins from the intermembrane space. These are then followed by caspase activation and eventually cell death. One of the strategies tumor cells use to resist death under growth factor or nutrient limitation is through up-regulation of the expression or activity of antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL-xL and AKT, which suppress apoptosis through their effects on cellular metabolic activities. One of the key functions of BCL-xL is to promote efficient mitochondrial ATP/ADP exchange through voltage-dependent anion channel/adenine nucleotide translocase (VDAC/ANT) complex to sustain coupled respiration in the face of decreased mitochondrial membrane potential,24 whereas AKT promotes glucose uptake and glycolysis that provide fuel to maintain mitochondrial potential and ATP production.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation is one of the early events in several forms of cell death. Although it is still controversial whether ROS production during apoptosis precedes or follows mitochondrial damage,25,26 scavenging of ROS blocks or attenuates apoptosis in several systems,27 and BCL2 has been shown to inhibit apoptosis by preventing ROS generation.28,29

As a known factor affecting metabolism, PPARγ may impact tumor cell survival through its regulation of cellular metabolism similar to other antiapoptotic proteins. In the current study, we investigated the role of PPARγ in the survival of tumor cells using anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) as a model. ALCL is a type of non-Hodgkin’s T-cell lymphoma characterized by large malignant cells with pleomorphic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm. It represents ∼2% of all types of lymphoma, ∼10% of pediatric lymphomas, and ∼50% of large cell lymphomas in the pediatric population. At the molecular level, ALCL is not a homogeneous entity; about 40 to 60% of cases carry a characteristic chromosomal translocation t(2;5), which generates a fusion between anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and nucleophosmin (NPM) gene.

We found that PPARγ is highly expressed in several primary tissues of ALCL cases. Under the condition of serum starvation, PPARγ agonists promote survival of an ALCL cell line that highly expresses the receptor but not of an ALCL line that lacks PPARγ. Moreover, decreasing the amount of PPARγ by RNA interference reduces the rate of cell survival. Given the role of PPARγ in metabolism, we investigated whether its prosurvival effects are linked to its regulation of cellular metabolic activities. We demonstrated that PPARγ activation leads to higher ATP and lower ROS levels that favor survival in serum-deprived cells. Moreover, PPARγ limits amount of ROS through concerted transcriptional regulation of several proteins and enzymes that control cellular ROS. Last, transfection of PPARγ into the PPARγ-null T-cell lymphoma cell line imparts increased survival and reduced ROS accumulation. The finding that PPARγ promotes survival is compatible with the observations that expression of PPARγ is increased in many cancers and suggests that PPARγ may confer a survival advantage on the malignant cells, allowing them to survive in an adverse environment.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Tissues

15d-PGJ2, rosiglitazone, and WY14643 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Paraffin-embedded tissues from nine cases of ALCL were obtained from the archives of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College and studied following Institutional Review Board review and approval.

Cell Lines and Culture

The anaplastic large cell lymphoma lines Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 have been described previously30–32 and were maintained at 37°C in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. SUP-M2 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-hPPARγ1 with TransFectin lipid reagent from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Serum Starvation and Cell Viability Determination

To perform serum withdrawal, cells were washed three times with RPMI 1640, resuspended, and cultured in serum-free media. Cell viability was determined by cellular exclusion of 2 μg/ml propidium iodide followed by flow cytometric analysis of 10,000 events as described previously.23 Various drug treatments of the cells are described in detail in figure legends.

Caspase-3 Activity

Caspase-3 activity was assayed using CaspGLOW fluorescein active caspase-3 staining kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA). Serum-starved cells (3 × 105 in 0.3 ml) were treated with 1 μl of caspase-3 substrates and incubated for 45 minutes in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were then washed with the wash buffer, and 10,000 events were analyzed by flow cytometry using FL-1.

Luciferase Assay

Five micrograms of acylCoAx3-TK-LUC, a Firefly luciferase reporter construct containing three copies of PPRE, and 0.5 μg of Renilla expression plasmid were cotransfected into 5 × 106 Karpas 299 cells using the Amaxa Nucleofector instrument (Amaxa Biosystems, BioCampus, Cologne, Germany) in 100 μl of solution V using the A30 program. Rosiglitazone (2 μmol/L) or DMSO vehicle control was added 16 hours after transfection. Cells were then harvested 24 hours after drug addition. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was measured using MLX microplate luminometer (Dynex Technologies Inc., Chantilly, VA). PPARγ transcriptional activity was expressed as firefly luciferase activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Immunohistochemical Assays

Immunohistochemical staining for PPARγ (E-8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and CD30 (clone BerH2; DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the TechMate 500 automated immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ). Immunostaining for PPARγ was performed following antigen retrieval in an autoclave using Target Retrieval Solution, High pH (DakoCytomation). Immunoreactivity for PPARγ was identified using HRP-labeled mouse Envision Plus detection system (DakoCytomation) and DAB liquid chromogen (DakoCytomation). The sections were then retrieved in the autoclave with Target Retrieval Solution, Citrate pH 6 (DakoCytomation), and immunostained for CD30 using ChemMate alkaline phosphatase detection system (Ventana Medical Systems). The alkaline phosphatase reaction was developed by BT Red reagent substrate provided in the kit. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted in Cytoseal-XYL (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI).

RNA Interference and Nucleofection

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) against PPARγ and scrambled double-stranded RNA controls were purchased from Dharmacon Inc. (Boulder, CO) in the form of SMART pool. The delivery of siRNA pools into Karpas 299 cells was performed using nucleofection technology with the Nucleofector instrument (Amaxa Biosystems). A total of 3 μg of the siRNA pools were delivered into 2 × 106 cells suspended in 100 μl of solution V using the A30 nucleofection program. Two micrograms of pmaxGFP vector were cotransfected to monitor transfection efficiency.

Measurement of Cellular ATP Levels

Intracellular ATP levels were determined using the ATP bioluminescence assay kit HS II (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 25 μl of lysis reagent was added to 25 μl of cells (1 × 105 cells/ml), incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature, and 50 μl of luciferase reagent was then added. Luminescence was quantified using a MLX microtiter plate luminometer (Dynex Technologies).

Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

At various time points following serum withdrawal, 2 × 105 to 4 × 105 cells were stained with 20 nmol/L tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester in a 37°C CO2 incubator for 30 minutes. Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry using FL-2.

Measurement of Intracellular ROS

Intracellular ROS were detected with carboxy-H2DCFDA (DCF; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Three hundred thousand cells were washed once, resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, and loaded with 10 μmol/L carboxy-H2DCFDA for 30 minutes at 37°C. DCF fluorescence of 10,000 events was measured by flow cytometry using FL-1.

RNA Preparation, Reverse Transcription, and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amounts of total RNA were quantified using spectrophotometric measurements. RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was conducted in an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System [Applied Biosystems (ABI), Foster City, CA]. cDNA made from 100 ng of total RNA was added to a 20 μl 1× Taqman Universal Master Mix (ABI). The PCR reactions were conducted at 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 se-conds and 60°C for 60 seconds. Primers and probe were purchased from ABI for detection of PPARγ (Hs00234592_m1), catalase (Hs00156308_m1), Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD, Hs00166575_m1), p67 (Hs00166416_m1), and UCP2 (Hs00163349_m1); sequences are not provided by the manufacturer. Manganese SOD (Mn-SOD) was detected using SYBR Green method. Primer sequences are: forward, 5′-AGCATGTTGAGCCGGGCAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-AGGTTGTTCACGTAGGCCGC-3′. Real-time PCR results were analyzed with ABI PRISM 7000 SDS software. Autothresholds and autobaselines determined by the software were applied to generate values of corresponding threshold cycles (Ct). Ct values of various genes were normalized to human β-actin that was purchased from ABI (Hs 99999903_m1).

Western Blot Analyses

The analyses were conducted as described previously.23 Antibodies against PPARγ, UCP2, and p67 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, TX), and BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ), respectively.

Assay for Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Activity

The activity of the enzyme was assayed in whole-cell extracts using a superoxide dismutase assay kit purchased from Cayman Chemical. The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To determine selectively the activity of Mn-SOD, cell lysates were treated with 3 mmol/L KCN to inactivate CuZn-SOD before performing the assay.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was used to perform the statistical analyses. P values are indicated in each figure.

Results

PPARγ Is Highly Expressed in Human T-Cell Lymphoma and Low Doses of Rosiglitazone Attenuate Serum Withdrawal-Induced Lymphoma Cell Death

Although expression of PPARγ has been found in mouse and human lymphoma cell lines, expression of PPARγ in human primary lymphoma tissues has not been demonstrated. We examined nine cases of ALCL for PPARγ expression by immunohistochemistry. To ensure that PPARγ is expressed in the malignant cells, we performed staining for PPARγ as well as CD30, which specifically marks the malignant large cells in ALCL tissues. Positive PPARγ staining was found in six of nine cases, and a pair of positive and negative cases is shown in Figure 1A. In a typical positive case, the malignant anaplastic large cells that are marked with cytoplasmic CD30 (pink) were stained positive for PPARγ (brown) in nuclei (Figure 1A, left panel), whereas a typical negative case lacks PPARγ staining in CD30-marked tumor cells (Figure 1A, right panel). The admixed positive and negative results among nine cases are not unexpected, because ALCL cases are not homogeneous at the molecular level.

Figure 1.

Expression of PPARγ in human T-cell lymphoma and effects of rosiglitazone on serum withdrawal-induced cell death. A: Medium power views of PPARγ-positive and -negative ALCL cases. Red, CD30 cytoplasmic staining; brown, PPARγ nuclear staining. B: PPARγ protein expression in Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 lymphoma cell lines. Immunohistochemical assay was performed on cell blocks made from the two cell lines. Nuclear staining is shown in brown. C: Survival of serum-deprived Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells in the presence or absence of rosiglitazone. Serum-deprived cells were cultured for various periods as indicated in the presence of 2 μmol/L rosiglitazone or DMSO. Cell survival was determined by propidium iodide exclusion with flow cytometric analysis. Data shown are mean ± SE of three independent experiments. D: Caspase-3 activity in serum-deprived Karpas 299 cells. Serum-deprived cells were cultured for 18 hours in the presence of 2 μmol/L rosiglitazone or DMSO. E: Dose titration of rosiglitazone. Serum-deprived Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of rosiglitazone at various concentrations as indicated and survival was determined at 48 hours after serum withdrawal. Data shown are mean ± SE of three independent experiments. F: Relative luciferase activity in Karpas 299 cells treated with DMSO or 2 μmol/L rosiglitazone. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase that was cotransfected into the cells. Luciferase activity of DMSO-treated cells was set as 1.

To facilitate studies of the function of PPARγ in lymphoma cell survival, two human ALCL lines, Karpas 299 and SUP-M2, were used.30,31 Karpas 299 cells express a high level of PPARγ revealed by both real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and Western blot analysis, whereas SUP-M2 shows little expression.33 Immunohistochemical staining on cell blocks made from these two cell lines confirmed the presence of the receptor in the nuclei of Karpas 299 cells and the absence of the receptor in SUP-M2 cells (Figure 1B).

Next, we examined whether high levels of PPARγ confer a survival advantage on the lymphoma cells under stress conditions. Serum starvation was performed with Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells treated with PPARγ ligand rosiglitazone or drug vehicle, and survival of the cells was determined by propidium iodide exclusion. Although survival of both Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells decreased with time, death of Karpas 299 cells was attenuated by rosiglitazone treatment, whereas survival of SUP-M2 cells was not influenced (Figure 1C). The cell death is apoptotic in nature, since caspase-3 was activated in serum-starved Karpas 299 cells (Figure 1D, DMSO). In addition, rosiglitazone treatment of the cells suppressed caspase-3 activation, supporting that the PPARγ agonist is prosurvival in serum-starved cells (Figure 1D, Rosi versus DMSO).

A dose titration of rosiglitazone revealed that the survival effect in Karpas 299 cells could be observed at a concentration as low as 0.5 μmol/L and reached maximum at 2 μmol/L (Figure 1E). These concentrations largely overlap with pharmacologically achievable serum concentrations of rosiglitazone in diabetic patients (0.16 to 1.26 μmol/L) (Rosiglitazone Maleate, http://home.mdconsult.com, 2006). In comparison, in the same dose range, rosiglitazone did not show any effects on the survival of SUP-M2 cells (Figure 1E). Two micromolar was chosen for the subsequent experiments. At this concentration, PPARγ was activated as a transcriptional factor as shown by a luciferase reporter assay (Figure 1F).

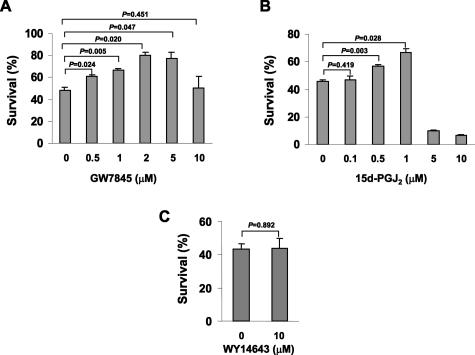

Low Doses of Other PPARγ but Not PPARα Agonists Promote Survival in Serum-Deprived Lymphoma Cells

To ensure that the survival effect is mediated via PPARγ rather than a special property of rosiglitazone, other PPARγ agonists were tested for their activities in serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis. GW7845, a tyrosine analogue that is chemically distinct from glitazones,34 promoted survival of the Karpas 299 cells in the dose range of 0.5 to 5 μmol/L but reduced survival at higher concentrations (Figure 2A). 15d-PGJ2, a potential physiological ligand of PPARγ, increased cell survival in the dose range of 0.1 to 1 μmol/L but killed cells at concentrations above and equal to 5 μmol/L (Figure 2B). Last, WY14643, a PPARα agonist, did not influence cell survival under this condition (Figure 2C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that low doses of PPARγ agonists attenuated serum withdrawal-induced lymphoma cell apoptosis, whereas high doses promoted cell death.

Figure 2.

Other PPARγ but not PPARα agonists promote cell survival. A: Survival of serum-deprived Karpas 299 cells in the presence of GW7845 at concentrations indicated. B: Survival of serum-deprived Karpas 299 cells in the presence of 15d-PGJ2 at concentrations indicated. C: Survival of serum-deprived Karpas 299 cells in the presence of WY14643 at concentrations indicated. Cell survival was determined at 42 hours after serum withdrawal and data shown are mean ± SE of three independent experiments.

Reducing the Amount of PPARγ with siRNA Decreases Survival in Serum-Deprived T Lymphoma Cells

To determine whether the prosurvival effect of the PPARγ agonists acts through the receptor, PPARγ in Karpas 299 cells was specifically inhibited using siRNA. A pool of four PPARγ siRNA was transfected into cells with an efficiency of ∼65% as assessed by the cotransfection of a green fluorescent protein-containing plasmid. The level of PPARγ transcripts was knocked down to ∼45% of the level in control cells transfected with scrambled double-stranded RNA (Figure 3A). Reduction of PPARγ protein was confirmed with Western blot analysis, and the effect on cell survival was then determined (Figure 3B). siRNA transfection decreased the survival of Karpas 299 cells in the presence or absence of rosiglitazone, confirming that prosurvival activity is dependent on PPARγ (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Reducing PPARγ attenuates survival in Karpas 299 cells. A: PPARγ mRNA levels in Karpas 299 cells transfected with PPARγ siRNA or control scrambled RNA. mRNA was measured by real-time RT-PCR at 48 hours after transfection. The level of PPARγ mRNA in control RNA-transfected cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. B: PPARγ protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis in whole-cell lysates at 48 hours after transfection. C: Cell viability was determined at 48 hours after serum starvation in the presence of DMSO or 2 μmol/L rosiglitazone. Results shown are mean ± SE of three independent experiments.

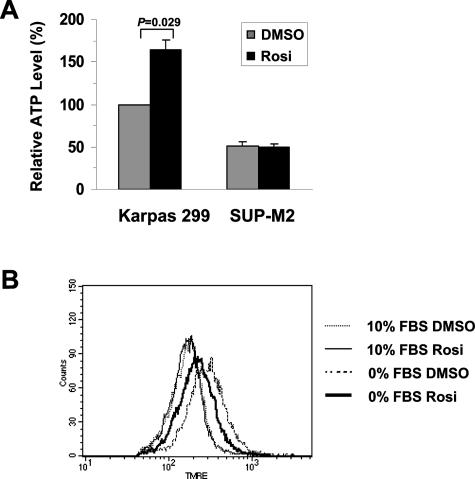

The Prosurvival Effect of PPARγ Is Accompanied by Increased Cellular ATP and Decreased Mitochondrial Hyperpolarization

ATP depletion is one of the early events during apoptotic death induced by growth factor withdrawal.24 In the next experiment, we investigated whether total cellular ATP level is affected by PPARγ activation following serum starvation. We compared ATP levels of Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells treated with or without rosiglitazone. As shown in Figure 4A, following serum withdrawal, cellular ATP in the Karpas 299 cells treated with rosiglitazone was significantly higher than those cells treated with DMSO, whereas rosiglitazone had no effect on the total ATP level in the SUP-M2 cells.

Figure 4.

PPARγ attenuates decline in ATP level and reduces mitochondrial hyperpolarization in serum-deprived cells. A: Relative ATP levels in Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells withdrawn from serum. Cells were cultured with or without 2 μmol/L rosiglitazone as indicated. Total cellular ATP levels were determined in lysates from a million cells at 40 hours after serum withdrawal. The amount of ATP in DMSO-treated Karpas 299 cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. Data shown are mean ± SE of three independent experiments. B: Mitochondrial membrane potential measured by tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester incorporation. Karpas 299 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of serum for 37 hours with or without rosiglitazone as indicated.

In growth factor-deprived cells, decline of cellular ATP and failure to exchange ADP and ATP between mitochondria and cytosol lead to hyperpolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane.24 In Karpas 299 cells, hyperpolarization was observed in 36 to 46 hours following serum withdrawal. As shown in Figure 4B, although rosiglitazone did not influence mitochondrial membrane potential in the presence of serum (thin solid versus thin dotted line), the addition of this drug during serum starvation resulted in a less polarized mitochondrial potential compared with DMSO treatment (thick solid versus thick dotted line). Taken together, these data suggest that the prosurvival effect of PPARγ is associated with maintenance of ATP production and reduced degree of mitochondrial hyperpolarization.

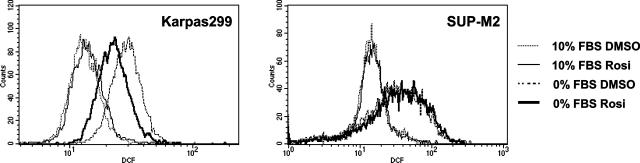

PPARγ Suppresses Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species in Serum-Deprived T Lymphoma Cells

ROS are generated following application of many apoptotic stimuli,25 and scavenge of ROS has been shown to prevent or delay cell death.27 We compared the levels of intracellular oxidants of the T lymphoma cells in the presence or absence of serum. Serum deprivation caused an increase in intracellular ROS in both Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells (Figure 5, thick solid and dotted lines versus thin solid and dotted lines). In serum-deprived Karpas 299 cells, rosiglitazone treatment led to a reduction in the ROS level (Figure 5, left panel, thick solid versus thick dotted line) whereas rosiglitazone did not influence the ROS level in serum-deprived SUP-M2 cells (Figure 5, right panel, thick solid versus thick dotted line). This result suggests that activation of PPARγ suppresses accumulation of ROS, thus leading to improved survival.

Figure 5.

ROS is suppressed in serum-deprived Karpas 299 cells by PPARγ activation but not in SUP-M2 cells. Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells were cultured with or without serum in the presence of DMSO or 2 μmol/L rosiglitazone as indicated. Cells were harvested at 48 hours after serum withdrawal and incubated with 10 μmol/L DCF at 37°C for 30 minutes. Ten thousand events in live cell gate were analyzed by flow cytometry.

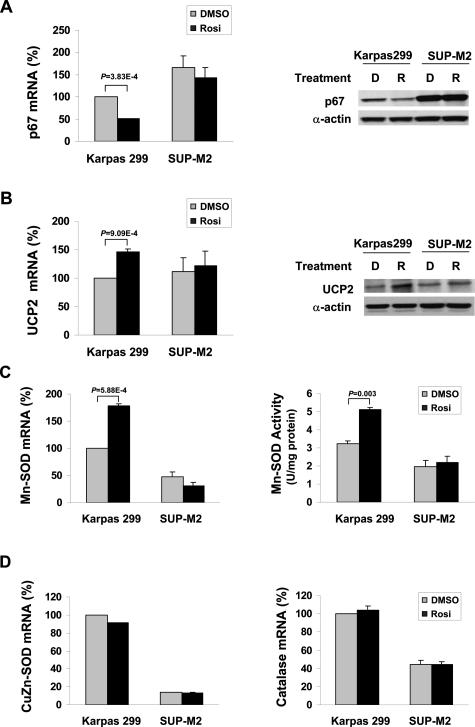

PPARγ Regulates a Set of Enzymes and Proteins That Controls Cellular ROS Level

PPARγ is known as a nuclear hormone receptor that acts as a transcription factor. The receptor may affect the cellular ROS through its transcriptional regulation of proteins and enzymes responsible for ROS generation and scavenge. Activation of NADPH oxidase produces many species of free radical oxidants. Recently, it has been shown that NADPH oxidase is expressed in the T lymphocytes,35 and expression of several subunits of NADPH oxidase, including p67, p22, and p47, is regulated by pioglitazone treatment of endothelial cells.36 Because the p67 subunit plays an important role in regulating the enzymatic activity of NADPH oxidase, we analyzed expression of p67 in serum-deprived T lymphoma cell lines. Real-time RT-PCR revealed that p67 mRNA expression was reduced by rosiglitazone treatment in Karpas 299 cells but not in SUP-M2 cells (Figure 6A, left panel). This observation was confirmed at the protein level by Western blot analysis (Figure 6A, right panel).

Figure 6.

A set of ROS regulating enzymes is coordinately controlled by PPARγ activation. Karpas 299 and SUP-M2 cells treated with 2 μmol/L rosiglitazone or DMSO were harvested at 42 hours after serum withdrawal. A: p67 mRNA was measured by real-time RT-PCR (left). The amount of p67 mRNA in DMSO-treated Karpas 299 cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. p67 protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis in whole-cell lysates (right). D, DMSO; R, rosiglitazone. B: UCP2 mRNA was measured by real-time RT-PCR (left). The amount of UCP2 mRNA in DMSO-treated Karpas 299 cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. UCP2 protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis in whole cell lysates (right). D, DMSO; R, rosiglitazone. C: Mn-SOD mRNA was measured by real-time RT-PCR (left). The amount of Mn-SOD mRNA in DMSO-treated Karpas 299 cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. Mn-SOD activity was determined in whole-cell lysates. D: CuZn-SOD and catalase mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. The amount of mRNA in DMSO-treated Karpas 299 cells was arbitrarily set as 100%. Data shown in A–D are mean ± SE of at least three independent experiments.

Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) plays a role in limiting mitochondrial ROS generation. Modulation of UCP2 expression by unsaturated fatty acids is thought to be mediated by PPARs. We observed a significant increase in UCP2 mRNA expression in Karpas 299 cells treated with rosiglitazone but not in SUP-M2 cells similarly treated (Figure 6B, left panel). Moreover, mRNA changes were accompanied by the corresponding changes at the protein level (Figure 6B, right panel).

Superoxide dismutase, an important ROS scavenger, is responsible for converting superoxide radicals into H2O2 and molecular oxygen. It has two cellular forms, a mitochondria-associated enzyme using Mn as a cofactor (Mn-SOD) and a cytosolic enzyme using copper and zinc as cofactors (CuZn-SOD). As shown in Figure 6C, PPARγ activation regulated the mRNA expression and enzymatic activity of Mn-SOD specifically in serum-deprived Karpas 299 cells but not in SUP-M2 cells. In contrast, CuZn-SOD was not affected by PPARγ activation in either cell line (Figure 6D, left panel). Expression of catalase, the enzyme that converts H2O2 to water and molecular O2, did not respond to rosiglitazone treatment either (Figure 6D, right panel). Taken together, we found that activation of PPARγ modulates expression of three ROS-controlling factors, p67 subunit of NADPH, UCP2, and Mn-SOD, thereby limiting the level of ROS and promoting cell survival.

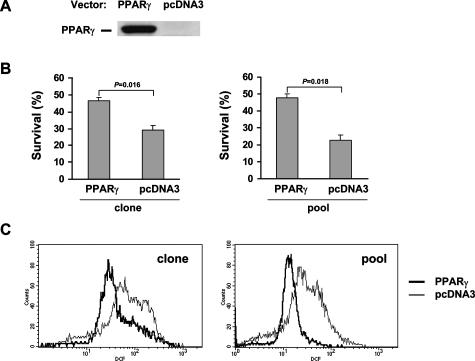

Transfection of PPARγ into PPARγ-Deficient SUP-M2 Cells Improves Cell Survival and Suppresses ROS Accumulation

To provide more definitive evidence that PPARγ promotes survival by suppressing ROS accumulation, PPARγ was stably transfected into the SUP-M2 lymphoma cell line that lacks the receptor (Figure 7A). Survival and ROS levels were then determined in these cells in comparison to SUP-M2 cells transfected with an empty vector. As shown in Figure 7B, during serum starvation, the survival of the PPARγ-positive SUP-M2 clone was significantly higher than the vector-transfected cells in the presence of rosiglitazone (Figure 7B, left panel). To exclude the possibility that this effect was due to properties of a specific clone, a pool of PPARγ-positive clones was then tested. Again, survival of the PPARγ-positive pool was significantly improved over the survival of the control pool (Figure 7B, right panel).

Figure 7.

Transfection of PPARγ into SUP-M2 cells improves cell survival and suppresses ROS accumulation. A: PPARγ or pcDNA3 vector was stably transfected into SUP-M2 cells. Western blot shows the presence or absence of the PPARγ protein expression in stable cell lines containing PPARγ expression vector or pcDNA3 vector. B: Cell survival in serum-deprived SUP-M2 cells with or without PPARγ. Rosiglitazone (2 μmol/L) was added at the time of serum withdrawal. Individual stable clones are shown on the left and pools of stably transfected cells are shown on the right. C: ROS levels in serum-deprived SUP-M2 cells with or without PPARγ. Rosiglitazone (2 μmol/L) was added at the time of serum withdrawal. Individual stable clones are shown on the left and pools of stably transfected cells are shown on the right.

We next investigated the effect of PPARγ transfection on ROS levels under the condition of serum deprivation. As shown in Figure 7C, the PPARγ-positive clone that exhibited a better survival rate (Figure 7B, left panel) had a much more reduced level of ROS than the control clone. This effect was confirmed by a similar observation with the PPARγ-positive and control pools of SUP-M2 clones (Figure 7C, right panel). Taken together, we demonstrated that PPARγ suppresses ROS accumulation and improves survival through a receptor-dependent mechanism.

Discussion

In this report, we provide several pieces of evidence showing that PPARγ confers cell survival in malignant T cells under the condition of serum withdrawal. First, activation of the receptor is capable of enhancing survival in Karpas 299 cells that highly express PPARγ but not in SUP-M2 cells that lack PPARγ. Not only the glitazone type of PPARγ agonists but also the other types of agonists (GW7845 and 15d-PGJ2) act to increase cell survival, whereas a PPARα agonist shows no effects. Second, reducing the level of the receptor in Karpas 299 cells with siRNA decreased cell survival rate. Third, cellular metabolic activities, including ATP, mitochondrial membrane potential, and ROS, are changed in directions that are consistent with PPARγ being a prosurvival factor. Fourth, several ROS controlling molecules are coordinately regulated by PPARγ activation in the directions that lead to ROS limitation. Lastly and importantly, introduction of the receptor into PPARγ-negative SUP-M2 cells results in increased cell survival and decreased ROS accumulation during serum starvation. Collectively, these observations support the notion that PPARγ promotes T lymphoma cell survival through regulation of cellular metabolic activities.

In addition to our report, several groups have found that PPARγ improves cell survival in other systems. Haraguchi et al37 reported that several PPARγ agonists inhibit serum starvation induced apoptosis in kidney cells. In addition, it has been shown that infusion of 15d-PGJ2 and rosiglitazone resulted in reduction in size of brain infarct38 as well as myocardial infarct in rats.39 These findings are consistent with our results that PPARγ attenuates cell death induced by nutrient/growth factor deprivation.

The role of PPARγ in cancer is controversial. Although several genetic models suggest that PPARγ promotes tumor formation when combined with other oncogenes, studies in vitro and using xenograft models have shown the antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of PPARγ agonists in a variety of tumor cells. Based on these studies, it has been proposed that PPARγ ligands may be used as anticancer agents. However, a careful review of the literature reveals that many of these studies used PPARγ ligands at concentrations much higher than their KD for PPARγ. In a study of PPARγ in leukemia, 25 μmol/L rosiglitazone are required to induce 50% cell death in leukemic cell lines,40 whereas a prosurvival effect can be seen at a concentration as low as 0.5 μmol/L. In patients taking rosiglitazone to control diabetes, maximum plasma concentration of the drug falls between 0.16 and 1.26 μmol/L following an oral dose of 1 to 8 mg. Likewise, micromolar doses of 15d-PGJ2 were required to induce lymphoma cell death,41,42 whereas physiological concentrations of the metabolite are in the range of picomolar to nanomolar. In our system, 15d-PGJ2 generated a small but dose-dependent increase in cell survival in the range of 0.1 to 1 μmol/L but induced cell death when doses were above 5 μmol/L. Similar to our observations, Lin et al.38 also found that high doses of PPARγ agonists 15d-PGJ2 (≥5 μmol/L) and rosiglitazone (≥10 μmol/L) cause cytotoxicity as indicated by lactate dehydrogenase release from cultured neurons, whereas low concentrations of the agonists (15d-PGJ2, ≤1 μmol/L, and rosiglitazone, 0.5 μmol/L) suppress rat and human neuronal apoptosis and necrosis induced by H2O2 treatment. Requirements for high doses of ligands suggest the possibility that apoptosis induction is an off-target effect independent of the receptor. A more definitive piece of evidence for the prosurvival role of PPARγ is derived from our study with genetic manipulation of the receptor. We showed that, on one hand, decreasing PPARγ level with siRNA in Karpas 299 cells impaired cell survival and, on the other hand, transfection of the receptor into SUP-M2 cells results in increased survival in serum-deprived cells.

Setoguchi and colleagues43 reported that proliferation and survival of B cells on LPS or IgM stimulation were increased in PPARγ heterozygous mice compared with the wild-type mice, suggesting that the receptor suppresses B cell proliferation and survival under physiological conditions. In the meantime, the proliferative response of T cells was not affected by reduced level of PPARγ in the haploinsufficient mice. So, B and T lymphocytes apparently responded differently to PPARγ activation in this study in terms of proliferation. Survival of T cells was not determined; thus, a direct comparison to our study is not possible. Importantly, we have found that PPARγ does not affect cell survival under normal conditions, it only does so when cells suffer from growth factor/nutrient deprivation.23,33 These data led us to believe that cellular conditions are crucial in dictating how cells respond to PPARγ activation.

As a metabolic regulator, how does PPARγ cause metabolic changes at the cellular level to favor cell survival when cells are deprived of growth factors/nutrients? Our data show that PPARγ attenuates the decline in ATP under conditions of serum withdrawal. In cells deprived of growth factor, a drop in cellular ATP reflects compromised mitochondrial function and is one of the steps leading to cell death. In this study, we showed that activation of PPARγ with rosiglitazone results in a higher ATP level in serum-deprived cells (Figure 4A). Moreover, hyperpolarization of mitochondrial membrane is alleviated by rosiglitazone treatment (Figure 4B). These data suggest that PPARγ helps maintain cellular ATP level in the face of nutrient deprivation leading to improved mitochondrial homeostasis and increased cell survival.

ROS generation is a necessary step during apoptosis as ROS scavengers block or delay apoptosis. We found that serum withdrawal-induced ROS production is attenuated by PPARγ activation in Karpas 299 cells but not in SUP-M2 cells. Moreover, introduction of PPARγ into SUP-M2 leads to ROS limitation in the transfected cells, providing strong evidence that PPARγ plays a key role in the regulation of ROS metabolism. Our investigation has further identified that proteins and enzymes regulating ROS are coordinately controlled by PPARγ. PPARγ increases the amount of UCP2 and Mn-SOD and reduces the amount of the p67 subunit of NADPH oxidase at both the mRNA and protein levels, leading to decreased ROS accumulation and increased cell survival. Together with the information in the literature, we have proposed a model showing the molecular and metabolic mechanisms underlying the prosurvival function of PPARγ (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanisms underlying the prosurvival function of PPARγ. The model was made based on findings in the current report and literature (see Discussion). Dashed arrow indicates that the effects may or may not be direct.

We have shown that PPARγ is highly expressed in primary lymphoma tissues and functionally contributes to malignant T-cell survival. Although PPARγ is unlikely to be solely responsible for the oncogenic transformation of the lymphoma cells, the receptor may sustain tumor cell survival under adverse conditions. As a matter of fact, the center of a three-dimensional tumor mass is often deprived of oxygen, growth factors, glucose, and other nutrients because of excessive demand and insufficient vascularization. However, unlike normal tissues, neoplastic cells possess remarkable tolerance and are able to survive despite the adverse environment.44,45 In light of findings in this report, activation of PPARγ is possibly one of the underlying mechanisms for this tolerance. Increased expression of PPARγ is found in many types of tumors, compatible with the notion that PPARγ is a prosurvival factor. However, the current study only focused on anaplastic large cell lymphoma, which is a subset of T-cell lymphomas. Further investigations need to be conducted to determine whether survival enhancement by PPARγ is a general mechanism in other types of tumors. In view of the current findings, careful further investigation into the role of PPARγ in tumorigenesis is required before widespread use of TZD in cancer therapy.

Our data also suggest cautionary use of TZD in diabetic patients with concurrent lymphomas or other types of cancers. Currently, over 1.6 million patients in the United States take TZD chronically to manage their diabetes. If PPARγ promotes tumor survival, alternative therapy should be considered in the treatment of this subpopulation of diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuanyuan Zhang for technical assistance and Pin Lu, M.D., Ph.D., for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Y. Lynn Wang, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 10021. E-mail: lyw2001@med.cornell.edu.

Supported by career award K08-HL068850 (to Y.L.W.) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

References

- Vamecq J, Latruffe N. Medical significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Lancet. 1999;354:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten S, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Roles of PPARs in health and disease. Nature. 2000;405:421–424. doi: 10.1038/35013000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouff C, Auwerx J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma calls for activation in moderation: lessons from genetics and pharmacology. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:899–918. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala SM, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes and metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS, Spiegelman BM, Mortensen RM. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein HJ, Demetri GD, Mueller E, Sarraf P, Spiegelman BM, Winer EP. Use of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma ligand troglitazone as treatment for refractory breast cancer: a phase II study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;79:391–397. doi: 10.1023/a:1024038127156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevener AL, He W, Barak Y, Le J, Bandyopadhyay G, Olson P, Wilkes J, Evans RM, Olefsky J. Muscle-specific Pparg deletion causes insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2003;9:1491–1497. doi: 10.1038/nm956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois RN, Gupta R, Brockman J, Reddy BS, Krakow SL, Lazar MA. The nuclear eicosanoid receptor, PPARgamma, is aberrantly expressed in colonic cancers. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:49–53. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarraf P, Mueller E, Jones D, King FJ, DeAngelo DJ, Partridge JB, Holden SA, Chen LB, Singer S, Fletcher C, Spiegelman BM. Differentiation and reversal of malignant changes in colon cancer through PPARgamma. Nat Med. 1998;4:1046–1052. doi: 10.1038/2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller E, Sarraf P, Tontonoz P, Evans RM, Martin KJ, Zhang M, Fletcher C, Singer S, Spiegelman BM. Terminal differentiation of human breast cancer through PPAR gamma. Mol Cell. 1998;1:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T, Koshizuka K, Williamson EA, Asou H, Said JW, Holden S, Miyoshi I, Koeffler HP. Ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (troglitazone) has potent antitumor effect against human prostate cancer both in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3344–3352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Singer S, Forman BM, Sarraf P, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CD, Brun RP, Mueller E, Altiok S, Oppenheim H, Evans RM, Spiegelman BM. Terminal differentiation of human liposarcoma cells induced by ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and the retinoid X receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:237–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll TG, Sarraf P, Pecciarini L, Chen C-J, Mueller E, Spiegelman BM, Fletcher JA. PAX8-PPARgamma 1 fusion oncogene in human thyroid carcinoma. Science. 2000;289:1357–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grommes C, Landreth GE, Heneka MT. Antineoplastic effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:419–429. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik L, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors and cancers: complex stories. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre AM, Chen I, Desreumaux P, Najib J, Fruchart JC, Geboes K, Briggs M, Heyman R, Auwerx J. Activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma promotes the development of colon tumors in C57BL/6J-APCMin/+ mice. Nat Med. 1998;4:1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez E, Tontonoz P, Nelson MC, Alvarez JG, Ming UT, Baird SM, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. Activators of the nuclear receptor PPARgamma enhance colon polyp formation. Nat Med. 1998;4:1058–1061. doi: 10.1038/2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez E, Rosenfeld J, Livolsi A, Olson P, Lombardo E, Nelson M, Banayo E, Cardiff RD, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Evans RM. PPAR gamma signaling exacerbates mammary gland tumor development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:528–540. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix L, Lazar V, Michiels S, Ripoche H, Dessen P, Talbot M, Caillou B, Levillain JP, Schlumberger M, Bidart JM. Follicular thyroid tumors with the PAX8-PPARγ1 rearrangement display characteristic genetic alterations. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62967-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seargent JM, Yates EA, Gill JH. GW9662, a potent antagonist of PPARgamma, inhibits growth of breast tumour cells and promotes the anticancer effects of the PPARgamma agonist rosiglitazone, independently of PPARgamma activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:933–937. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer KL, Wada K, Takahashi H, Matsuhashi N, Ohnishi S, Wolfe MM, Turner JR, Nakajima A, Borkan SC, Saubermann LJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ inhibition prevents adhesion to the extracellular matrix and induces anoikis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2251–2259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Frauwirth KA, Rangwala SM, Lazar MA, Thompson CB. Thiazolidinedione activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ can enhance mitochondrial potential and promote cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31781–31788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT, Thompson CB. Bcl-xL prevents cell death following growth factor withdrawal by facilitating mitochondrial ATP/ADP exchange. Mol Cell. 1999;3:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb E, Vander Heiden MG, Thompson CB. Bcl-x(L) prevents the initial decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequent reactive oxygen species production during tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5680–5689. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5680-5689.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci JE, Gottlieb RA, Green DR. Caspase-mediated loss of mitochondrial function and generation of reactive oxygen species during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:65–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Sagara Y, Liu Y, Maher P, Schubert D. The regulation of reactive oxygen species production during programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1423–1432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery D, Oltvai Z, Yin X, Milliman C, Korsmeyer S. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane DJ, Sarafian TA, Anton R, Hahn H, Gralla EB, Valentine JS, Ord T, Bredesen DE. Bcl-2 inhibition of neural death: decreased generation of reactive oxygen species. Science. 1993;262:1274–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.8235659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L, Aytac U, Stephens LC, Ohnuma K, Mills GB, McKee KS, Neumann C, LaPushin R, Cabanillas F, Abbruzzese JL, Morimoto C, Dang NH. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effect of the anti-CD26 monoclonal antibody 1F7 on human CD30+ anaplastic large cell T-cell lymphoma Karpas 299. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2031–2040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SW, Kirstein MN, Valentine MB, Dittmer KG, Shapiro DN, Saltman DL, Look AT. Fusion of a kinase gene ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene NPM, in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Science. 1994;263:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.8122112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovic M, Sarin PS, Robert-Gurroff M, Kalyanaraman VS, Mann D, Minowada J, Gallo RC. Isolation and transmission of human retrovirus (human T-cell leukemia virus). Science. 1983;219:856–859. doi: 10.1126/science.6600519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Yang C, Miao Q, Marzec M, Wasik MA, Lu P, Wang YL. PPARγ promotes lymphocyte survival through its actions on cellular metabolic activities. J Immunol. 2006;177:3737–3745. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh N, Wang Y, Honda T, Gribble GW, Dmitrovsky E, Hickey WF, Maue RA, Place AE, Porter DM, Spinella MJ, Williams CR, Wu G, Dannenberg AJ, Flanders KC, Letterio JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ, Nathan CF, Nguyen L, Porter WW, Ren RF, Roberts AB, Roche NS, Subbaramaiah K, Sporn MB. A novel synthetic oleanane triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid, with potent differentiating, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory activity. Cancer Res. 1999;59:336–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SH, Devadas S, Kwon J, Pinto LA, Williams MS. T cells express a phagocyte-type NADPH oxidase that is activated after T cell receptor stimulation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:818–827. doi: 10.1038/ni1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue I, Goto S, Matsunaga T, Nakajima T, Awata T, Hokari S, Komoda T, Katayama S. The ligands/activators for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) and PPARgamma increase Cu2+, Zn2+-superoxide dismutase and decrease p22phox message expressions in primary endothelial cells. Metabolism. 2001;50:3–11. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.19415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi K, Shimura H, Onaya T. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma inhibits apoptosis induced by serum deprivation in LLC-PK1 cells. Exp Nephrol. 2002;10:393–401. doi: 10.1159/000065303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TN, Cheung WM, Wu JS, Chen JJ, Lin H, Liou JY, Shyue SK, Wu KK. 15d-prostaglandin J2 protects brain from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:481–487. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201933.53964.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Tl TL, Chen J, Bao W, Narayanan PK, Bril A, Jiang W, Lysko PG, Gu JL, Boyce R, Zimmerman DM, Hart TK, Buckingham RE, Ohlstein EH: In vivo myocardial protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazone. Circulation 2001, 104:2588–2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopleva M, Elstner E, McQueen TJ, Tsao T, Sudarikov A, Hu W, Schober WD, Wang R-Y, Chism D, Kornblau SM, Younes A, Collins SJ, Koeffler HP, Andreeff M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and retinoid X receptor ligands are potent inducers of differentiation and apoptosis in leukemias. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1249–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla J, Kaur K, Cao HJ, Smith TJ, Phipps RP. Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-gamma agonists and 15-deoxy-Δ(12,14)(12,14)-PGJ(2) induce apoptosis in normal and malignant B-lineage cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:6941–6948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SG, Phipps RP. Prostaglandin D(2), its metabolite 15-d-PGJ(2), and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma agonists induce apoptosis in transformed, but not normal, human T lineage cells. Immunology. 2002;105:23–34. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi K, Misaki Y, Terauchi Y, Yamauchi T, Kawahata K, Kadowaki T, Yamamoto K. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma haploinsufficiency enhances B cell proliferative responses and exacerbates experimentally induced arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1667–1675. doi: 10.1172/JCI13202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV, Semenza GL. Oncogenic alterations of metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuishi K, Kato K, Ogura T, Kinoshita T, Esumi H. Remarkable tolerance of tumor cells to nutrient deprivation: possible new biochemical target for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6201–6207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]