Abstract

Reactive astrocytes and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease surround amyloid plaques and secrete proinflammatory cytokines that affect neuronal function. Relationship between cytokine signaling and amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) accumulation is poorly understood. Thus, we generated a novel Swedish β-amyloid precursor protein mutant (APP) transgenic mouse in which the interferon (IFN)-γ receptor type I was knocked out (APP/GRKO). IFN-γ signaling loss in the APP/GRKO mice reduced gliosis and amyloid plaques at 14 months of age. Aggregated Aβ induced IFN-γ production from co-culture of astrocytes and microglia, and IFN-γ elicited tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α secretion in wild type (WT) but not GRKO microglia co-cultured with astrocytes. Both IFN-γ and TNF-α enhanced Aβ production from APP-expressing astrocytes and cortical neurons. TNF-α directly stimulated β-site APP-cleaving enzyme (BACE1) expression and enhanced β-processing of APP in astrocytes. The numbers of reactive astrocytes expressing BACE1 were increased in APP compared with APP/GRKO mice in both cortex and hippocampus. IFN-γ and TNF-α activation of WT microglia suppressed Aβ degradation, whereas GRKO microglia had no changes. These results support the idea that glial IFN-γ and TNF-α enhance Aβ deposition through BACE1 expression and suppression of Aβ clearance. Taken together, these observations suggest that proinflammatory cytokines are directly linked to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis.

Accumulating evidence supports the idea that neuroinflammation plays a significant role in the neuropathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1,2 Amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) aggregation and accumulation, a principal part of AD neuropathology, is linked directly to disease progression3 and is regulated and directly affected by innate immune responses.4–6 Indeed, Aβ modulates microglial inflammatory responses and abilities and speed at which microglia digest and clear this protein from brain underlines disease severity.7

Aβ is processed from the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP). This is accomplished by processing enzymes (secretases), which include the β-site APP-cleaving enzyme (BACE1, a β-secretase)8 as well as the γ-secretase complexes of presenilin (PS)-1, aph-1, pen-2, and nicastrin.9 Mutant forms of PS-1, PS-2, and APP genes are transmitted as autosomal dominants in early onset familial AD (FAD) and are linked to Aβ aggregation and deposition.10 Transgenic mice expressing Swedish FAD APP mutant (Tg2576)11 mimic pathobiological features of human disease including neural dysfunction, amyloid deposition, and neuroinflammation.12–14 Each disease component affects one another. Indeed, for neuroinflammation, chronic expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1/CCL2, a major mononuclear phagocyte chemoattractant, recruits monocytes and macrophages into the brain and enhances diffuse plaque formation in APP/CCL2 bigenic mice.15 Moreover, proinflammatory cytokines, such as interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-1β, transforming growth factor (TGF)-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α are up-regulated in APP mice and can affect neural function.16–19 Tg2576 mice deficient for CD40 ligand show a marked reduction of Aβ deposition, micro- and astrogliosis, and APP β-processing.20 Thus, proinflammatory factors can play roles in AD pathogenesis.

IFN-γ, a regulatory cytokine for mononuclear phagocyte (monocyte, macrophage, dendritic cell, and microglial cell) activation and inflammation, is produced and secreted by activated T cells and natural killer cells.21 It can also be made, to a lesser degree, by astrocytes, macrophages, and microglia.22,23 The potent and diverse actions of this cytokine may lead to adverse consequences for the central nervous system. For example, IFN-γ, IFN-inducible Fas, and caspase-1 are up-regulated in trisomy 16 mice, a neurodegenerative animal model of Down syndrome.24 Higher levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 are present in AD brains when compared with age-matched controls.25 Reduced glial inflammation in response to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis was previously demonstrated in IFN-γ-deficient mice.26 However, despite these observations, the effect of IFN-γ on AD progression is poorly understood. Thus, to better define the role played by IFN-γ in disease, we generated APP mice in which the IFN-γ receptor type 1 (GR) gene was knocked out (GRKO).27 In the present study, APP/GRKO mice were used to investigate the role of glial inflammation in amyloid deposition and clearance. We now demonstrate that IFN-γ and TNF-α enhance Aβ deposition through BACE1 expression and lead to changes in Aβ clearance. These data, taken together, support the notion that proinflammatory cytokines affect the pathogenesis of AD.

Materials and Methods

APP/GRKO Mice

Tg2576 mice expressing the Swedish mutation of human APP695 were obtained from Drs. G. Carlson and K. Hsiao-Ashe through the Mayo Medical Venture.11 Tg2576 mice were backcrossed to 129S1/Sv four times, followed by crossing with GRKO mice (strain 129-Ifngr1tm1Agt/J; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) in a 129S1/Sv background to generate APP/GR+/− mice. The APP/GR+/− males were intercrossed to GR+/− females to generate APP/GR+/+ (APP) and APP/GR−/− (APP/GRKO) littermates for study comparisons. Animals used for this study were APP (APP transgene-positive and GR wild type, 14 months; two males and three females), APP/GRKO (APP transgene-positive and GRKO, 14 months; one males and four females), GRKO (APP transgene-negative and GRKO, 14 months; two males and three females), and wild-type (WT, APP transgene-negative, and GR wild type, 14 months; two males and three females) mice. The APP, APP/GRKO, GRKO, and WT mice are littermates.

Genotyping Protocol

DNA samples were prepared from cut tail tips (<1.0 cm) of individual pups, and genomic DNA was extracted using the Easy DNA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as described previously to identify APP transgene-positive mice.28 The GR gene targeting was confirmed by PCR of genomic DNA with four primers: oIMR013, oIMR014, oIMR0587, and oIMR0588 (primer sequence and genotyping protocol posted on http://jaxmice.jax.org).

Protein Extraction and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The animals were perfused with ice-cold normal saline, and brains were rapidly removed and bisected sagittally. A piece of frontal cortex was dissected and frozen for biochemical analysis (protein extraction, immunoblotting, and ELISA). The remainder of the brains were prepared for histological tests (frozen or paraffin-embedded) of the two hemibrains. For immunoblotting and cytokine ELISA tests, brain tissues were homogenized in solubilization buffer [50 mmol/L Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-sodium, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN)] and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 hour at 4°C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was quantified by BCA (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and subjected to immunoblotting. For total Aβ ELISA, brain tissues were homogenized in 5 mol/L-guanidine isothiocyanate to prepare a protein extract29 and subjected to Aβ40 and Aβ42 ELISA (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were euthanized with isoflurane and perfused transcardially with 25 ml of normal (0.9%) saline as described.15,30 The brains were rapidly removed, and the frontal cortex was dissected and frozen until biochemical analysis. The brain region including hippocampus was immersed in freshly depolymerized 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours and bisected sagittally. The left hemispheres were cryoprotected by successive 24-hour immersions in 10, 20, and 30% sucrose in Sorenson’s phosphate buffer immediately before sectioning. Fixed, cryoprotected brains were frozen and sectioned in the horizontal plane at 10 μm using a Cryostat (Leica Microsystems Inc., Bannockburn, IL), with sections collected serially. The right hemispheres were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. Immunohistochemistry was performed using specific antibodies to identify cellular and molecular markers for BACE1 (rabbit polyclonal antibody; EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), CD11c (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1 (IBA1, rabbit polyclonal antibody; kindly provided by Dr. S. Kohsaka),31 MHC class II (BD Biosciences, Rockville, MD), CD45 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC), and phosphotyrosine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) antibodies as described.15 Brain sections were additionally stained with thioflavin-S (Sigma) to localize deposits of amyloid in a β-sheet configuration. Two regions were examined quantitatively using a stereological system: the hippocampus and the cortex. On the other hand, paraffin-embedded brains were stained for Aβ (rabbit polyclonal antibody, Invitrogen) or glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, rabbit polyclonal antibody; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Systematic uniform random sets of sections with 300-μm spacing were used for staining. All immunohistochemistry was visualized using avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine for color development (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Envision Plus kit (DAKO) was used instead of avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase for Aβ staining. Immunofluorescence for BACE1 and GFAP was performed using anti-BACE1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (EMD Biosciences), anti-GFAP (mouse monoclonal antibody, mAb; Sigma), Alexa 594-conjugated anti-rabbit, and Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Invitrogen).

Confocal Microscopic Imaging

Thirty μm frozen sections of APP or APP/GRKO cortical regions were permeabilized and blocked with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 5% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 minutes, followed by double staining for BACE1 (1:500 dilution) and NeuN (mouse mAb, 1:200 dilution; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) or GFAP (mouse mAb, 1:200 dilution; Sigma). After washing with PBS/0.1% Triton X, the sections were incubated with Alexa 568-conjugated anti-rabbit and Alexa 647-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) and counterstained with a derivative of 10 μmol/L Congo red (E,E)-1-fluoro-2,5-bis(3-hydroxycarbonyl-4-hydroxy) styrylbenzene (FSB; Dojindo, Gaithersburg, MD), which specifically binds to the β-sheet conformation of Aβ plaques with an excitation/emission wavelength of 390/511 nm. Of note, there is no overlap between Alexa 568 or Alexa 647 excitation/emission wavelengths.32,33 After mounting the sections on slides with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories), the confocal images of Aβ plaque regions were captured using a Nikon SweptField slit-scanning confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments, New York, NY) with a 100× TIRF objective and back-illuminated charge-coupled device camera Cascade 512B (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ), with excitation at 488 (for FSB), 568 (for Alexa 568), and 647 nm (for Alexa 647) lasers. The images were pseudocolored, autocontrasted, and merged as tricolor images (see Figure 8).

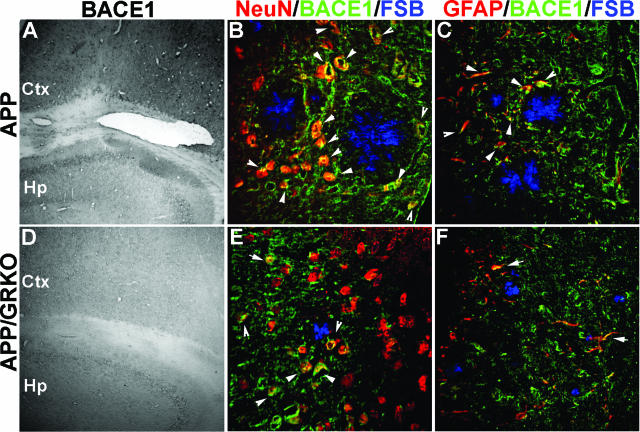

Figure 8.

BACE1 expression in APP and APP/GRKO mice. A–F: Ten- or 30-μm-thick slices of cortical and hippocampal regions of APP (A–C) and APP/GRKO mice (D–F) at 14 months of age were immunostained with anti-BACE1 rabbit polyclonal antibody and developed with DAB (Ctx, cortical region; Hp, hippocampal region). For confocal imaging, anti-BACE1 antibody was labeled with anti-rabbit Alexa 568 secondary antibody (B, C, E, F, green), double stained with anti-NeuN (for neuronal staining; B, E, red) or GFAP (for astrocyte staining; C, F, red) mAb, which were labeled with anti-mouse Alexa 647 secondary antibody and counterstained with Congo Red analog FSB (for Aβ plaque staining; B, C, E, F, blue). The fluorescence-stained sections were subjected to confocal microscopic imaging using Nikon SweptField laser confocal imaging system and pseudocolored for Alexa 568 (green), Alexa 647 (red), and FSB (blue). Arrows in B, C, E, and F indicate co-localization of BACE1 with NeuN (B, E) or GFAP (C, F). Original magnifications: ×40 (A, D); ×400 (B, C, E, F).

Image Analysis

Images were captured with a digital camera (DVC-1310C; DVC Company, Austin, TX) attached to an Eclipse TE-300, Nikon microscope using C-View v1.2 software (DVC Company).15,34 Ten to twenty images, covering the entire cortical and hippocampal areas, were taken per each 5- or 10-μm section (10 sections per brain, 300 μm spacing) at ×200 magnification. The measured outcome of total volume occupied by TS and Aβ immunohistochemical reaction was quantified by image software (NIH Image 1.62). Immunopositive cells (BACE1, GFAP, and IBA1 staining) were counted manually. Data are reported as a percentage of the total stained area divided by the total cortical or hippocampal area or the total number of immunostained cells divided by the total cortical or hippocampal area for each animal. Two investigators in blinded manner analyzed the immunohistochemical tests.

Immunoblots

Brain lysates (30 μg) were precleared with 10 μl of protein G-Sepharose FF (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) to remove endogenous mouse IgG and subjected to standard immunoblotting for apolipoprotein E (apoE, rabbit polyclonal antibody; Biodesign, Saco, ME), APP (6E10 mouse mAb; Signet, Dedham, MA), APP C-terminal fragments (CTF, rabbit polyclonal antibody; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), BACE1 (rabbit polyclonal antibody), β-actin (mouse mAb; Sigma), HA-tag (HA-7, mouse mAb; Sigma), inducible nitric-oxide synthase (NOS-2, rabbit polyclonal antibody; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE, rabbit polyclonal antibody; Oncogene Science, Cambridge, MA), and neprilysin (CD10, mouse mAb; Novocastra Laboratory, Newcastle on Tyne, UK) as described.15,35 Alkaline phosphatase or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used against mouse and rabbit IgG (1:2000 dilution; Vector Laboratories), and developed using NBT/BCIP solution (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) or chemiluminescence.15,35 The images were digitally captured by a computer scanner at 1200 dpi, and band intensities were quantified by NIH Image 1.62 software. Data are presented as a ratio of target band intensity/β-actin.

Tissue Culture and Recombinant Adenovirus Infection

Primary cultured mouse astrocytes and/or astrocytes-microglia were prepared from WT and GRKO newborn pups as described and plated (5 × 104 cells/well in poly-d-lysine-coated 24-well plates) in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, and 50 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (all from Invitrogen). On examination of astrocyte purity by immunocytochemistry (GFAP for astrocytes and Hoechst 33342 for nuclear staining), if purity was more than 90%, cells were infected with recombinant adenovirus-expressing Swedish APP mutation (APPsw: MOI = 10) as described previously35 and stimulated with murine IFN-γ or TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 24 hours. Primary cultured mouse microglia was prepared from WT and GRKO day 0 newborn pups as described.36 In brief, dissociated and trypsinized newborn mouse cortices were cultured as mixed glial culture in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum, heat-inactivated 5% horse serum, and 50 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (all from Invitrogen). Microglia released in the tissue culture media by shaking were collected at 14 days after the plating. After confirmation of their purity to be more than 90% by immunocytochemistry (CD11b for microglia, GFAP staining for contaminated astrocytes, and Hoechst 33342 for nuclear staining), cells were used for co-culture experiments with astrocytes or stimulated with IFN-γ for TNF-α and NOS-2 expression studies. Primary culture of mouse cortical neurons were prepared from WT and GRKO E16–17 embryo and plated (1.5 × 105 cells/well in poly-d-lysine-coated 24-well plates) in neurobasal media with 1× B27 supplement and 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate (all from Invitrogen) as described.37 On determining that glial contamination was less than 15% by standard immunocytochemistry (GFAP staining for contaminated astrocytes, microtubules associated protein-2 for differentiated neurons, and Hoechst 33342 for nuclear staining), neurons were infected with APPsw adenovirus and stimulated with IFN-γ or TNF-α as described. The cells and tissue culture media were harvested for APP, BACE1, and β-actin immunoblotting and Aβ, IFN-γ, and TNF-α ELISA.

Aβ Degradation Assay

Aβ degradation was investigated using 125I-Aβ40 as described.38 Iodinated Aβ40 was prepared using IODO beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL), synthetic Aβ40 peptide (amino acids 1 to 40; Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) and 125I (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacture’s instruction. 125I-Aβ40 was aggregated at 37°C for 3 days with agitation and used at the final concentration of 1 μmol/L (200,000 cpm/ml). Primary cultured microglia from WT or GRKO neonates (5 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates) were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, washed extensively, and incubated with chasing media for 120 hours. The media (secreted Aβ) were collected and cells were lysed in lysis buffer (1 mol/L NaOH) for γ-counting of intracellular Aβ. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA, Sigma) was subsequently added to the media to a final concentration of 10% for polypeptide precipitation by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The radioactivity of TCA-soluble (degraded Aβ) and precipitable (undegraded Aβ) fractions was determined by γ-ray counter for calculating the Aβ intracellular retention, secretion, and degradation ratio as a percent total 125I-Aβ counts.

Statistics

All data were normally distributed. In case of multiple mean comparisons, data were analyzed by analysis of variances, followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison tests using statistics software (Prism 4.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). In case of single mean comparison, data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as a significant.

Results

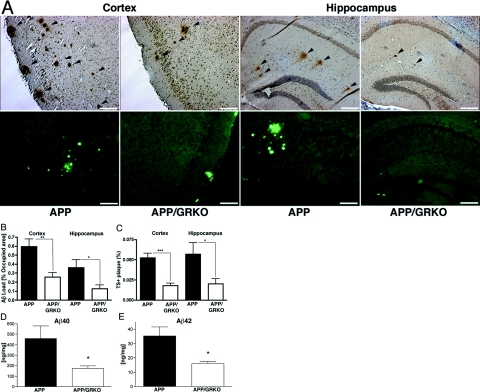

GRKO Reduces Both Diffuse and Compact Amyloid Plaque Deposition

Comparisons between APP/GRKO and their APP littermates were made in neuropathological examinations of Aβ. APP/GRKO mice showed significantly reduced Aβ deposition as determined by Aβ immunostaining of both cortical and hippocampal diffuse plaques at 14 months of age (Figure 1A, top). Quantitative immunohistochemical assays showed a 57 and 65% reduction in Aβ deposition in the cortex and hippocampus, respectively, in APP/GRKO mice (Figure 1B). The number of TS-positive (TS+) compact, especially large compact plaques (>160 μm in diameter), were reduced in APP/GRKO mice in both the cortex and hippocampus [Figure 1, A (bottom) and C]. Interestingly, the number of small compact plaques (<40 μm) was not altered (data not shown). Measures of total Aβ40 and Aβ42 by ELISA confirmed the data set (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Aβ and compact plaque deposition in APP/GRKO mice. A: Ten slides of 5- (Aβ) or 10-μm-thick (TS) brain sections of APP or APP/GRKO mice were immunostained with anti-Aβ antibody, developed with DAB, and counterstained with hematoxylin (top) or were stained with TS (bottom). The arrows indicate immunopositive Aβ deposits. B and C: Average percent area occupied by Aβ deposits (B) or TS+ compact plaques (C) as quantified by image analyses of immunochemically stained slides (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus APP mice as determined by Student’s t-test, respectively. D and E: Total Aβ40 and Aβ42 in cortex quantified by specific Aβ ELISA at 14 months of age (n = 5 per group). *P < 0.05 versus APP mice as determined by Student’s t-test. Scale bars = 200 μm. Original magnifications, ×100.

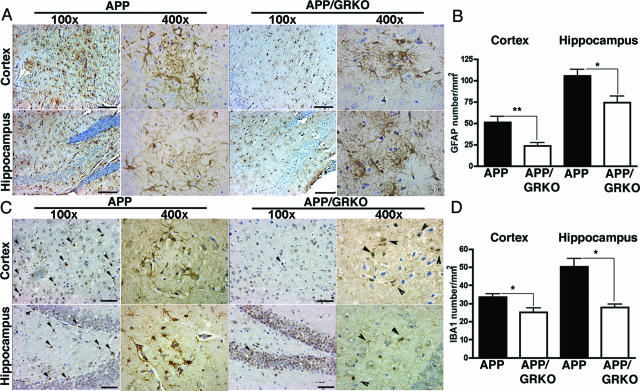

GRKO and Reduced Astro- and Microgliosis

Reduced Aβ deposition correlated with reduced astrocyte numbers in both the cortex and the hippocampus of APP/GRKO mice as assessed by GFAP immunostaining (Figure 2A, cortical and hippocampal region for low- and high-power magnifications). GFAP+ astrocytes were reduced in the cortex and the hippocampus of APP/GRKO mice by 61 and 30%, respectively, when compared with their APP littermates (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained for analysis of microgliosis as performed by IBA1 staining (Figure 2C, cortical and hippocampal region for low- and high-power magnifications). The number of IBA1+ microglia was significantly reduced in APP/GRKO mice as compared with their APP littermates (Figure 2D) and in GRKO mice as compared with their WT littermates (data not shown). These IBA1+ microglia showed reduced or absent CD45, MHC class II, CD11c, or phosphotyrosine immunostaining in all animal groups (data not shown). These data support the notion that the GRKO phenotype elicits reductions in both astro- and microgliosis.

Figure 2.

Astrogliosis and mononuclear phagocyte accumulation in APP/GRKO mouse brains. A: APP and APP/GRKO mice at 14 months of age (n = 5) were tested for astrogliosis by anti-GFAP staining. Images show 5- (GFAP) or 10-μm-thick (IBA1, C) coronal sections of the cortical and hippocampal region along with high-power magnification of Aβ plaque regions. B: Quantitative analysis of the number of GFAP-positive astrocytes. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01 versus APP as determined by Student’s t-test, respectively. C: Adjacent sections were immunostained with anti-IBA1 antibody and counterstained with hematoxylin. Arrows indicate IBA1+ cells in the brain regions, and their high-power magnification of Aβ plaque regions. D: Quantification of IBA1+ mononuclear phagocyte in brain regions. *P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test. Scale bars: 100 μm (A); 50 μm (C).

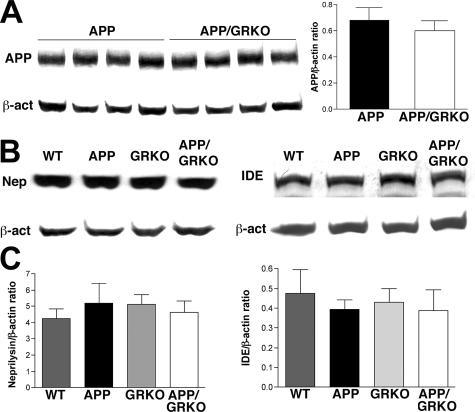

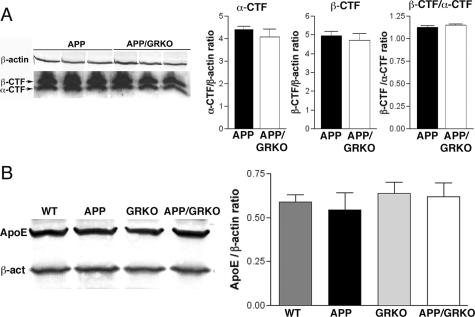

APP- or Aβ-Degrading Enzymes Are Not Affected by GRKO

The balance between production, aggregation, and Aβ clearance determines the extent of Aβ deposition. Although Aβ deposition was reduced in APP/GRKO mice at 14 months of age, significant differences were not found in APP expression between APP and APP/GRKO mice in the cortex of both animal groups (Figure 3A). In addition, the cortex levels of the Aβ degradation enzymes, IDE and neprilysin,39,40 were equivalent in WT, APP, GRKO, and APP/GRKO mice (Figure 3, B and C). Because this reflects the Aβ-degrading enzyme levels, the data suggested that Aβ degradation was not affected by GRKO. Neither the levels nor ratios of α/β processing were altered in APP/GRKO compared with APP mice as determined by immunoblotting of APP C-terminal fragments (Figure 4A). The expression level of apoE, which affects Aβ aggregation in brains,41,42 was also unchanged among the four animal groups (Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

APP- and Aβ-degrading enzyme expression. A: Protein extracts from the cortex of APP/GRKO and APP mice (n = 5) were subjected to immunoblotting for APP and β-actin using anti-Aβ (6E10) and anti-β-actin mAbs. The APP-immunoreactive band intensity was normalized by β-actin band intensity. No statistical significance was observed. B: Protein extracts (30 μg/lane) from the frontal cortex of four mouse groups at 14 months of age (n = 5) were subjected to immunoblotting using anti-neprilysin, anti-IDE, and anti-β-actin mAbs. C: The band intensity of neprilysin and IDE in B was normalized by the β-actin signal, and the average intensity ratios were presented. No statistical significance was observed by analysis of variance test.

Figure 4.

α/β-CTFs and apoE levels. A: Protein extracts from the cortex of APP/GRKO and APP mice (n = 5) were subjected to immunoblotting for APP α/β-CTFs and β-actin using anti-APP C-terminal antibody (CT-20, Calbiochem) and anti-β-actin mAbs. The α/β-CTF band intensity was normalized by β-actin band intensity. No statistical significance was observed in α-CTF/β-actin ratio, β-CTF/β-actin ratio, or β-CTF/α-CTF ratio between APP and APP/GRKO mice. B: Protein extracts (30 μg/lane) from the frontal cortex of four mouse groups at 14 months of age (n = 5) were subjected to immunoblotting using anti-apoE and anti-β-actin mAbs. The band intensity of apoE was normalized by the β-actin signal and the average intensity ratios were presented. No statistical significance was observed by analysis of variance.

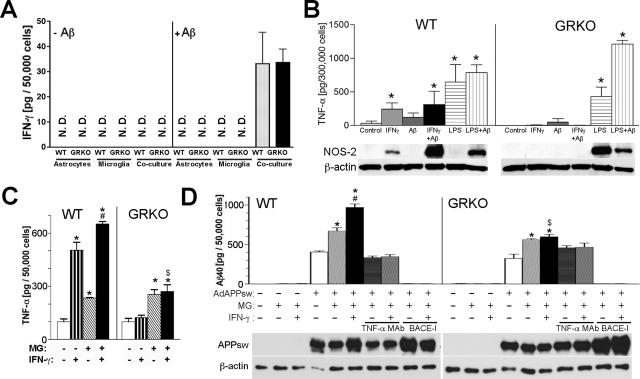

IFN-γ, TNF-α, and Aβ Production from Astrocytes and Microglia

To understand the molecular interaction of IFN-γ expression and Aβ deposition, we tested whether endogenous IFN-γ and TNF-α were up-regulated in brain tissue of APP and APP/GRKO mice. Cytokines were not detected by ELISA, suggesting their scarcity in the brain (data not shown). We then examined whether aggregated Aβ induces IFN-γ glial expression. Primary cultures of astrocytes and microglia, or co-cultures of astrocytes and microglia from WT or GRKO neonates were stimulated with aggregated Aβ25-35 (Figure 5A).43,44 Although no basal IFN-γ production was observed in any of the primary astrocytes or microglia cultures, significant IFN-γ production was observed in astrocytes and microglia co-cultures after Aβ stimulation regardless of genetic background. This suggested that astrocytes and microglia interactions are necessary for IFN-γ production. Next, we examined whether IFN-γ stimulates glial TNF-α production. As shown in Figure 5B, IFN-γ stimulated TNF-α production in primary cultures of microglia cells from WT but not GRKO mice, whereas lipopolysaccharide stimulated TNF-α production in both WT and GRKO primary microglial cultures. Moreover, IFN-γ, but not lipopolysaccharide, stimulated NOS-2 expression in WT microglia (Figure 5B). However, IFN-γ failed to induce NOS-2 expression in GRKO microglia. Interestingly, lipopolysaccharide stimulation induced NOS-2 expression in GRKO microglia, suggesting an alteration in IFN-γ-specific NOS-2 induction signaling in GRKO cells. To test whether TNF-α production is involved in Aβ production, primary cultures of astrocytes from WT or GRKO neonates were infected with adenovirus expressing APP Swedish mutant (APPSw),35 followed by co-culture with microglia and IFN-γ stimulation (Figure 5C). The adenovirus system was used because our initial attempts to measure Aβ production from astrocytes derived from APP transgene-positive pups were not successful. TNF-α production was enhanced when astrocytes were co-cultured with microglia regardless of genotype (Figure 5C). IFN-γ strongly stimulated TNF-α production from WT but not from GRKO co-cultured glia. As a control, we stimulated uninfected and GFP adenovirus-infected WT astrocytes with a combination of IFN-γ and microglia. Microglia with or without IFN-γ stimulation increased TNF-α production, although the amount of TNF-α is lower than APPsw-expressing astrocytes (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). IFN-γ stimulation alone did not increase TNF-α production in GFP adenovirus-infected or -uninfected astrocytes. These data support the idea that Aβ produced from APPsw-expressing astrocytes may aggregate and act as a co-stimulatory molecule to stimulate IFN-γ or microglia-induced TNF-α production in astrocytes. This TNF-α up-regulation is correlated with a significantly increased Aβ production from co-cultured WT glia, which is further enhanced by IFN-γ stimulation (Figure 5D). This is not attributable to the up-regulation of APP expression, as shown by immunoblotting for full-length APP (Figure 5D, bottom). Treatment of the astrocytes with a BACE inhibitor (BACE-I) completely blocked Aβ production, demonstrating its dependence on BACE enzyme activity. As a control, Aβ production from control WT or GRKO astrocytes without APPsw expression was undetectable. Most importantly, this IFN-γ-induced increase of Aβ production from co-cultured glia was completely blocked by co-incubation with an anti-TNF-α neutralizing monoclonal antibody (TNF-α mAb, Figure 5D), suggesting that TNF-α mediates Aβ production.

Figure 5.

Cytokines and Aβ production from primary cultured astrocytes and microglia. A: Primary cultured astrocytes (50,000 cells/well), microglia (MG, 50,000 cells/well), or astrocytes and microglia co-cultures (50,000 cells each/well) from WT or GRKO neonates were incubated in the absence (−Aβ) or presence of aggregated Aβ25-35 (+Aβ, 20 μg/ml) for 24 hours, and secreted murine IFN-γ levels were determined by ELISA. B: Top: Primary cultured microglia (300,000 cells/well) from WT or GRKO neonates were stimulated with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), aggregated Aβ40 (10 μg/ml), or lipopolysaccharide (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours, and secreted murine TNF-α levels were determined by ELISA. *P < 0.05 versus control of the same group as determined by analysis of variance and Newman-Keuls post hoc. Bottom: NOS-2 protein expression in the same set of primary cultured microglia. Expression of β-actin was used as a loading control. C: Primary cultured astrocytes (50,000 cells/well) from WT or GRKO neonates were infected with 1.0 MOI adenovirus expressing APPsw (100% GFP expression efficiency), and co-cultured with or without microglia (MG, 50,000 cells/well) of the same genetic background, followed by stimulation with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 24 hours and quantification of secreted murine TNF-α by ELISA. D: Top: The same tissue culture media of C was subjected to Aβ40 ELISA. Additional groups included the co-culture of astrocytes and microglia co-incubated with neutralizing anti-TNF-α mAb (10 μg/ml) with or without IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), treatment with 1 μmol/L BACE1 inhibitor (BACE-I), and astrocytes without adenovirus infection with or without microglia co-culture. Bottom: Full-length HA-tagged APPsw protein expression in the same set of astrocyte/microglia co-culture blotted by anti-HA antibody. Expression of β-actin was used as a loading control. C and D: *, #, and $ denotes P < 0.05 versus unstimulated astrocytes with or without microglia of the same genetic background as determined by analysis of variance and Newman-Keuls post hoc, respectively. $P < 0.05 versus WT astrocytes with microglia stimulated by IFN-γ by Student’s t-test.

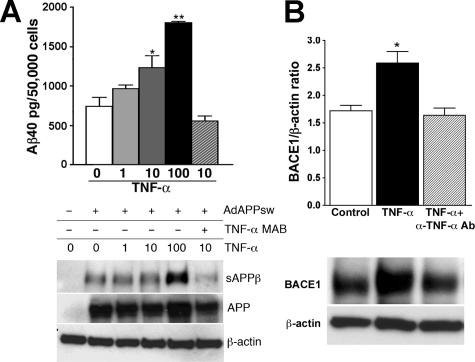

TNF-α Enhances Astrocyte BACE1 Expression and Aβ Production

To directly demonstrate TNF-α-induced Aβ production from astrocytes, astrocyte primary cultures from WT neonates were infected with APPsw adenovirus and stimulated with increasing doses of TNF-α for 24 hours, and Aβ production was determined. TNF-α stimulation increased Aβ40 levels in primary astrocytes in a dose-dependent manner and could be inhibited by anti-TNF-α-neutralizing antibody (Figure 6A). Aβ42 was similarly up-regulated on TNF-α stimulation (data not shown). Full-length APP expression measured after TNF-α stimulation was comparable among groups (Figure 6A, bottom). The increase in Aβ production by TNF-α stimulation correlates with an increase of secreted β-processing product of APP (sAPPβ) in the tissue culture media, supporting the idea that β-processing was induced by TNF-α. It was recently reported that stimulation of astrocytes with IFN-γ and TNF-α induces the expression of BACE1 in vitro and that BACE1 is up-regulated in plaque-associated GFAP+ astrocytes in Tg2576 mice in vivo.45–47 Thus, we have examined whether TNF-α stimulates BACE1 expression in astrocytes. As expected, an up-regulation of astrocyte’s BACE1 expression was observed after TNF-α stimulation, which was blocked by an anti-TNF-α-neutralizing antibody (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

TNF-α-stimulated astrocytes enhance Aβ production and BACE1 expression. A: Top: Aβ40 ELISA of tissue culture media collected from astrocyte primary cultures isolated from WT or GRKO neonates 24 hours after APPsw adenovirus infection and TNF-α (1, 10, and 100 ng/ml) stimulation or APPsw adenovirus infection and 10 ng/ml TNF-α plus 10 μg/ml α-TNF-α mAb stimulation. Bottom: The same set of tissue culture media (100 μl) was subjected to immunoprecipitation with 20 μg of 6E10 mAb (against Aβ1-17 sequence) overnight at 4°C to deplete Aβ and sAPPα. Supernatant after the immunodepletion was subjected to immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody, showing sAPPβ. Expression of full-length APP (APP) was examined by cell lysates. Expression of β-actin was used as a loading control. B: Cell lysates from astrocyte primary cultures isolated from WT or GRKO neonates stimulated by murine TNF-α (10 ng/ml) with or without anti-TNF-α antibody (α-TNF-α mAb, 10 μg/ml) for 24 hours, were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-BACE1 polyclonal antibody. The immunoprecipitated fraction was subjected to immunoblotting using anti-BACE1. The BACE1 band intensity was normalized against the β-actin level in the original cell lysate.

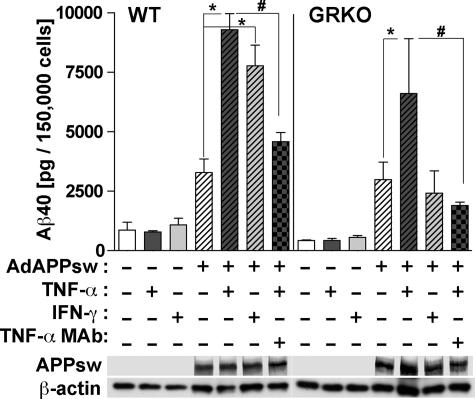

IFN-γ and TNF-α Enhance Neuronal Aβ

Because Aβ is mainly produced from neurons and considering the reduction of Aβ deposition in APP/GRKO mice in vivo, it is possible that IFN-γ and TNF-α also modulate neuronal Aβ production. To address this issue, differentiated primary culture of mouse cortical neurons derived from E16 WT and GRKO embryos were infected with APPsw adenovirus followed by IFN-γ and TNF-α stimulation. As shown in Figure 7, both IFN-γ and TNF-α significantly increased Aβ production in WT neurons (*P < 0.01 for WT and P < 0.05 for GRKO neurons). The TNF-α-induced Aβ production was threefold higher than the unstimulated control and was blocked by co-incubation of TNF-α with anti-TNF-α-neutralizing antibody (#P < 0.05), demonstrating its cytokine specificity. TNF-α, but not IFN-γ, increased Aβ production from GRKO neurons, demonstrating that the IFN-γ-induced stimulation of Aβ production is mediated through GR. These data demonstrate that IFN-γ and TNF-α stimulate Aβ production from neurons.

Figure 7.

Aβ expression in primary cultured neuron. Top: Primary cultured mouse cortical neurons (150,000 cells/well in 24-well plates) from E16 WT or GRKO embryos were infected with 1.0 MOI adenovirus expressing APPsw, followed by stimulation with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) with or without neutralizing anti-TNF-α mAb (10 μg/ml) for 24 hours. The tissue culture media was subjected to Aβ40 ELISA. * or # denotes P < 0.05 versus APPsw or APPsw + TNF-α in the same genotype as determined by analysis of variance and Newman-Keuls post hoc. Bottom: Expression of APPsw in cell lysates of primary cultured neurons. Expression of β-actin was used as a loading control.

BACE1 Expression in APP and APP/GRKO Mice

We examined whether BACE1 is up-regulated in aged APP or APP/GRKO mouse brain by immunohistochemistry. We observed a diffuse intense staining of BACE1 in the cortical region of APP mice but not in APP/GRKO mice (Figure 8, A and D). BACE1 immunoreactivity was localized to neurons surrounding Aβ plaques as observed by confocal images of brain sections triple stained with antibodies to BACE (green), NeuN (red), and Aβ plaques (Congo Red analog FSB, blue) (Figure 8, B and E) and partially co-localized with astrocytes (GFAP in red, BACE in green, and FSB in blue; Figure 8, C and F). These data suggest that although BACE1 is principally expressed in neurons, activated astrocytes surrounding the Aβ plaque also express the enzyme and that the overall BACE expression is reduced in the cortical region of APP/GRKO mice as compared with APP animals.

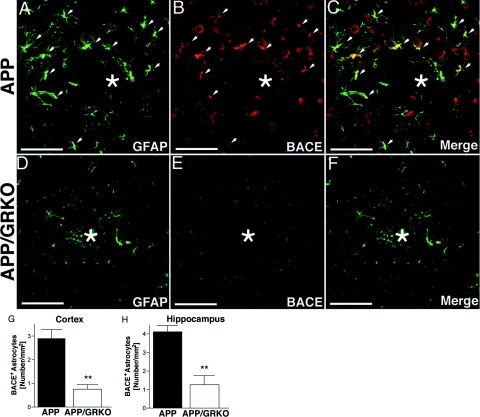

To confirm whether BACE1 is up-regulated in reactive astrocytes in APP and APP/GRKO mice in vivo, we examined the expression of BACE1 in GFAP+ astrocytes (Figure 9). GFAP− cells expressing BACE1 were neurons (data not shown). Although activated astrocytes are found commonly around plaques, the number of BACE1+ neurons remained constant in both APP and APP/GRKO mice (Figure 9, A and B and D and E). Nonetheless, a significant reduction in the number of BACE1+ astrocytes was seen in APP/GRKO mice (Figure 9, D–F) as compared with APP littermates (Figure 9, A–C), with 74% in the cortex and 70% in the hippocampus (Figure 9, G and H). These observations suggest that IFN-γ signaling affects Aβ production through microglial TNF-α stimulation of astrocyte BACE1 expression.

Figure 9.

BACE1 expression in activated astrocytes in vivo. A–F: Ten-μm-thick slices of cortical and hippocampal regions of mice at 14 months of age (n = 5) were immunostained with anti-GFAP monoclonal (green) (A, D) and anti-BACE1 polyclonal (red) (B, E) antibodies and images merged (C, F). Arrows indicate GFAP+/BACE1+ cells in the brain regions, and * denotes amyloid deposition. G and H: Quantification of BACE1+ astrocytes in cortex (G) and hippocampus (H). **P < 0.01 as determined by Student’s t-test. Scale bars = 100 μm. Original magnifications, ×200.

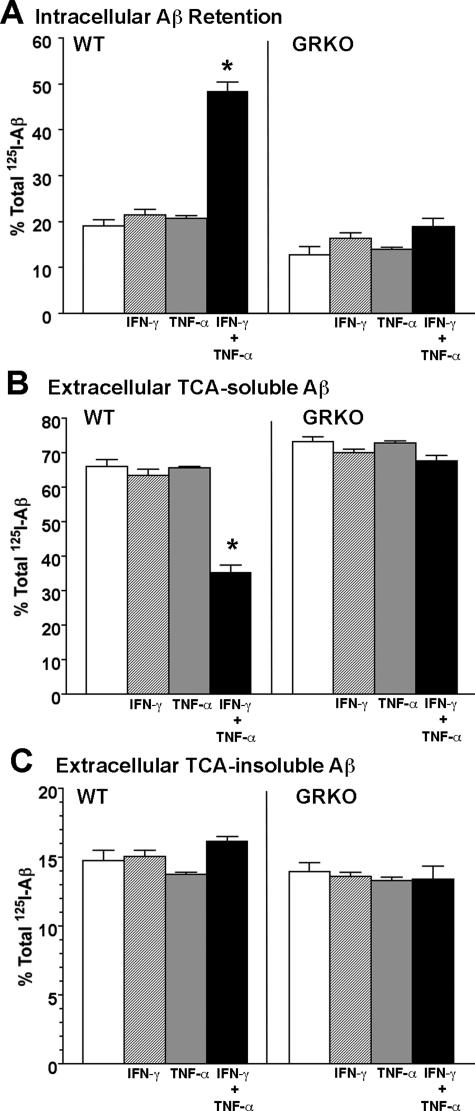

IFN-γ and TNF-α Suppress Microglial Aβ Degradation

Because glial cells, particularly microglia, are significantly involved in the clearance of aggregated Aβ in brain parenchyma, it is possible that cytokines modulate Aβ degradation in microglia. To study this, microglia primary cultures from WT and GRKO neonates were pulse-labeled with aggregated 125I-Aβ40, and chased for 120 hours with or without IFN-γ and/or TNF-α stimulation. The basal uptake of 125I-Aβ 1 hour after the initial incubation was ∼70% of total input, with no difference observed between WT and GRKO microglia (Supplemental Figure S2, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). At the end point, 125I-Aβ in the microglia and the tissue culture media were treated with TCA to separate degraded (TCA-soluble) and undegraded (TCA-precipitable) 125I-Aβ. As shown in Figure 10, co-stimulation of WT microglia with IFN-γ and TNF-α but not stimulation by IFN-γ treatment or TNF-α treatment alone shows a significant increase of intracellular Aβ retention (Figure 10A). Because more than 95% of intracellular Aβ is TCA-precipitable (data not shown), this suggests that intracellular Aβ degradation is significantly reduced. Intracellular Aβ retention was not affected by cytokine stimulation in GRKO mice, suggesting that suppression is dependent on IFN-γ. This was correlated with reduced TCA-soluble Aβ secretion from IFN-γ and TNF-α co-stimulated WT astrocytes (Figure 10B). TCA-insoluble Aβ secretion, which is a minor fraction of the overall Aβ metabolism, was unaffected by either genotype or cytokine treatment (Figure 10C). Taken together, these data suggest IFN-γ and TNF-α reduce Aβ clearance in WT but not GRKO microglia. The data also provide an explanation for the reduced Aβ deposition observed in APP/GRKO mice.

Figure 10.

IFN-γ- and TNF-α-stimulated microglia reduce Aβ degradation. Primary cultured microglia from WT or GRKO neonates (50,000 cells/well) were pulse-labeled with aggregated 125I-Aβ40 (100,000 cpm/well) for 1 hour and chased with fresh tissue culture media for 120 hours in the presence or absence of IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml). After chase, total cell lysates were collected and subjected to γ-counting, which represents intracellular 125I-Aβ retention. A–C: The tissue culture media were subjected to 10% TCA precipitation to separate extracellular TCA-soluble (B) and -insoluble (C) 125I-Aβ. Each fraction was presented as percent total 125I-Aβ (a sum of each fraction for each group). *P < 0.05 versus control of the same group as determined by analysis of variance and Newman-Keuls post hoc.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate a unique role for IFN-γ signaling in Aβ production and deposition in APP mice. A prominent role for IFN-γ is supported by several observations. 1) GRKO reduces both astro- and microgliosis in both the hippocampus and the cortex of APP mice; 2) reduced gliosis is accompanied by similarly reduced Aβ deposition (diffuse and compact); 3) IFN-γ stimulation enhances Aβ expression in glial co-cultures, which is blocked by anti-TNF-α neutralizing antibody; 4) TNF-α stimulates astrocyte Aβ production and BACE1 expression; 5) GRKO significantly reduces the BACE1 expression of reactive astrocytes in vivo; and 6) co-stimulation of IFN-γ and TNF-α suppress microglial Aβ clearance. These data taken together suggest that glial activation participates in enhanced Aβ deposition through IFN-γ, TNF-α, and BACE1 expression, and reduced Aβ clearance. Because there were no demonstrable differences in APP and APP/GRKO mice in APP expression, α/β-processing, apoE-, or Aβ-degrading enzymes, it is likely that the reduced Aβ deposition is attributable to reduced Aβ production and is not through suppressed Aβ clearance by cytokines in APP/GRKO mice.

How glial inflammation leads to enhanced Aβ deposition is unknown. Treatment of APP mice with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) results in reduced glial inflammation and Aβ deposition.48,49 Because NSAIDs also affect γ-secretase complex-mediated processing of APP, these studies were not conclusive in addressing the question of how glial inflammation affects Aβ deposition. Using the APP/GRKO transgenic mice, we have now specifically addressed whether suppression of glial inflammation by disruption of IFN-γ signaling, a prototypical T-cell-mediated proinflammatory cytokine, affects Aβ deposition in vivo. We demonstrated a significant correlation between reduced Aβ plaque formation and reduced glial inflammation in APP/GRKO mice. Previously studies reported that both IFN-γ and IL-12 are up-regulated in microglia and astrocytes in Tg2576.16 Thus, our study suggests a significant role for IFN-γ in the crosstalk between astrocytes and microglia during brain inflammation and in disease.

We have demonstrated that IFN-γ affects Aβ generation through stimulating TNF-α. TNF-α levels are elevated in AD serum,50 CSF, and cortex.51 Although there are a number of studies on the neurotoxic or neurotrophic action of TNF-α,1 limited information is available on its effect on APP processing. IFN-γ and TNF-α induce enhanced Aβ production from not only astrocytes but also transformed neuronal cells in vitro.52,53 Our data suggest that this is attributable to the crosstalk of glial cells, which induces BACE1 up-regulation. This finding is supported by a report that IFN-γ induces BACE1 expression in U373MG astrocytoma cells.47 As an alternative mechanism, IFN-γ and TNF-α can also modestly enhance γ-secretase-mediated processing of APP in COS-7 and human embryonic kidney 293 cells.54 Although we did not see a significant difference in the total amount of α- and β-CTF, the γ-secretase substrates, between APP and APP/GRKO mice, this could be an additional mechanism of reduced Aβ production in APP/GRKO mice.

Studies on postmortem AD brain showed BACE1 up-regulation in both mRNA and its enzyme activity.55–57 The correlation of BACE1 up-regulation and glial inflammation has been reported in not only Tg257647 but also other APP transgenic mice (APP V717I).58 Our finding of reduced BACE1 expression in APP/GRKO mice is consistent with a report on APP/CD40L-KO mice, in which they found reduced Aβ deposition, reduced gliosis, and reduced β-processing of APP.20 Our study suggests that their findings are attributable to a reduced BACE1 expression mediated by the lack of CD40 signaling. Because CD40 belongs to the TNF receptor family, they share common intracellular signaling for BACE1 gene induction, such as the TNF receptor-associated factor 6 recruitment to the cytoplasmic domain, the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, and AP-1 transcriptional factor complex. Interestingly, five potential NF-κB responsive elements were found in the proximal promoter region of human BACE1,59 suggesting an NF-κB-inducible gene expression mechanism in the BACE1 promoter regions.

Recently, Monsonego and colleagues60 reported that another APP mouse model (J20) crossed with IFN-γ-overexpressing mice had a slightly reduced Aβ plaque burden in dentate gyrus but not in the CA1 region after immunization with Aβ10-24 at 9 to 10 months of age. Their data suggest that low doses of IFN-γ are necessary for the induction of meningoencephalitis in APP mice but that IFN-γ effect on Aβ clearance is modest when compared with the effect of Aβ vaccination. It would be interesting to see whether higher transgene expression of IFN-γ could alter Aβ deposition in brains of APP mice at a later time point. This is necessary to study the effect of aging in these models. Although they show that IFN-γ enhanced Aβ uptake in microglia, we have observed a reduced Aβ degradation by IFN-γ/TNF-α-stimulated WT microglia, but no significant difference in Aβ uptake between WT and GRKO microglia. This suggests that the mechanism of Aβ uptake and its degradation are differentially regulated by IFN-γ in microglia.

In summary, we have demonstrated that APP/GRKO mice show reduced Aβ plaque deposition, astro- and microgliosis, and astrocyte BACE1 expression. The observations made are significant because TNF-α produced by IFN-γ-stimulated microglia directly correlates with increased Aβ expression from APPsw-expressing astrocytes and neurons and correlated with increased BACE1 expression. Our data suggest that IFN-γ and TNF-α signaling may also affect Aβ degradation in microglia. BACE1 may play a critical role not only in the regulation of Aβ production but also in providing a novel mechanism for AD progression, in which chronic glial activation leads to the acceleration of amyloid deposition attributable to enhanced BACE1 expression. Therapeutic strategies that reduce the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and BACE1 could lead to attenuation of glial Aβ and could lead to novel strategies for AD treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. G. Carlson and K. Ashe for providing Tg2576 mice; Drs. S. Barger, G. Landreth, and M. Vitek for critical reading of the manuscript; Dr. Y. Persidsky for consultation of neuropathology; Dr. A. Ghorpade for consultation of primary culture of astrocytes and microglia; Dr. S. Kohsaka for IBA1 antibody; and Dr. X. Luo and G. Weber for the transgenic mouse colony maintenance and genotyping.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Tsuneya Ikezu, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Neuroscience, 985880 Nebraska Medical Center, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-5880. E-mail: tikezu@unmc.edu.

Supported by the Vada Oldfield Alzheimer Research Foundation (to T.I.) and the National Institutes of Health (grant P01NS043985 to H.E.G. and T.I.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, Cooper NR, Eikelenboom P, Emmerling M, Fiebich BL, Finch CE, Frautschy S, Griffin WS, Hampel H, Hull M, Landreth G, Lue L, Mrak R, Mackenzie IR, McGeer PL, O’Banion MK, Pachter J, Pasinetti G, Plata-Salaman C, Rogers J, Rydel R, Shen Y, Streit W, Strohmeyer R, Tooyoma I, Van Muiswinkel FL, Veerhuis R, Walker D, Webster S, Wegrzyniak B, Wenk G, Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, Mucke L. Inflammation in neurodegenerative disease—a double-edged sword. Neuron. 2002;35:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton CA, Mott RT, Sharpe H, Xu Q, Vannostrand WE, Vitek MP. Expression profiles for macrophage alternative activation genes in AD and in transgenic mouse models of AD. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekabsone A, Mander PK, Tickler A, Sharpe M, Brown GC. Fibrillar beta-amyloid peptide Abeta1-40 activates microglial proliferation via stimulating TNF-alpha release and H2O2 derived from NADPH oxidase: a cell culture study. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. Modulation of microglial activation state following passive immunization in amyloid depositing transgenic mice. Neurochem Int. 2006;49:190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Landreth GE. Microglial phagocytosis induced by fibrillar beta-amyloid and IgGs are differentially regulated by proinflammatory cytokines. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8240–8249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1808-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, Teplow DB, Ross S, Amarante P, Loeloff R, Luo Y, Fisher S, Fuller J, Edenson S, Lile J, Jarosinski MA, Biere AL, Curran E, Burgess T, Louis JC, Collins F, Treanor J, Rogers G, Citron M. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B. Aph-1, Pen-2, and nicastrin with presenilin generate an active gamma-secretase complex. Neuron. 2003;38:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, Bird TD, Hardy J, Hutton M, Kukull W, Larson E, Levy-Lahad E, Viitanen M, Peskind E, Poorkaj P, Schellenberg G, Tanzi R, Wasco W, Lannfelt L, Selkoe D, Younkin S. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Tanzi RE, Borchelt DR, Sisodia SS. Alzheimer’s disease: genetic studies and transgenic models. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:461–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Hirai K, Hsiao K, Pappolla MA, Harris PL, Siedlak SL, Tabaton M, Perry G. Amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer transgenic mice is associated with oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2212–2215. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70052212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frautschy SA, Yang F, Irrizarry M, Hyman B, Saido TC, Hsaio K, Cole GM. Microglial response to amyloid plaques in APPsw transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:307–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Horiba M, Buescher JL, Huang D, Gendelman HE, Ransohoff RM, Ikezu T. Overexpression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1/CCL2 in beta-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice show accelerated diffuse beta-amyloid deposition. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1475–1485. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62364-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas N, Bednar I, Mix E, Marie S, Paterson D, Ljungberg A, Morris C, Winblad B, Nordberg A, Zhu J. Up-regulation of the inflammatory cytokines IFN-gamma and IL-12 and down-regulation of IL-4 in cerebral cortex regions of APP(SWE) transgenic mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;126:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzing WC, Wujek JR, Ward EK, Shaffer D, Ashe KH, Younkin SG, Brunden KR. Evidence for glial-mediated inflammation in aged APP(SW) transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:581–589. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apelt J, Schliebs R. Beta-amyloid-induced glial expression of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in cerebral cortex of aged transgenic Tg2576 mice with Alzheimer plaque pathology. Brain Res. 2001;894:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NS, Paris D, Mathura V, Quadros AN, Crawford FC, Mullan MJ. Inflammatory cytokine levels correlate with amyloid load in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Town T, Crawford F, Mori T, DelleDonne A, Crescentini R, Obregon D, Flavell RA, Mullan MJ. Role of CD40 ligand in amyloidosis in transgenic Alzheimer’s mice. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1288–1293. doi: 10.1038/nn968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H, Hardy K. Role of interferon-gamma in immune cell regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fultz M, Barber S, Dieffenbach C, Vogel S. Induction of IFN-γ in macrophages by lipopolysaccharide. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1383–1392. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Simone R, Levi G, Aloisi F. Interferon-gamma gene expression in rat central nervous system glial cells. Cytokine. 1998;10:418–422. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam DM, Capps NL, Travelstead AL, Brewer GJ, Maroun LE. Evidence for an interferon-related inflammatory reaction in the trisomy 16 mouse brain leading to caspase-1-mediated neuronal apoptosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;110:66–75. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman M, Shalit F, Roth-Deri I, Gutman B, Brodie C, Kott E, Sredni B. Correlation of cytokine secretion by mononuclear cells of Alzheimer patients and their disease stage. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;52:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran EH, Prince EN, Owens T. IFN-gamma shapes immune invasion of the central nervous system via regulation of chemokines. J Immunol. 2000;164:2759–2768. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao KK, Borchelt DR, Olson K, Johannsdottir R, Kitt C, Yunis W, Xu S, Eckman C, Younkin S, Price D, Iadecola C, Brent Clark H, Carlson G. Age-related CNS disorder and early death in transgenic FVB/N mice overexpressing Alzheimer amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 1995;15:1203–1218. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Motter R, Hu K, Gordon G, Barbour R, Khan K, Gordon M, Tan H, Games D, Lieberburg I, Schenk D, Seubert P, McConlogue L. Amyloid precursor protein processing and A beta42 deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1550–1555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen PT, Connor KE, DiCarlo G, Wenk GL, Wallace JL, Rojiani AM, Coppola D, Morgan D, Gordon MN. Microglial activation and beta-amyloid deposit reduction caused by a nitric oxide-releasing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug in amyloid precursor protein plus presenilin-1 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2246–2254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02246.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Ibata I, Ito D, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatibility complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:855–862. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Higuchi M, Iwata N, Saido TC, Sasamoto K. Fluoro-substituted and 13C-labeled styrylbenzene derivatives for detecting brain amyloid plaques. Eur J Med Chem. 2004;39:573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M, Suzuki N, Taniguchi S, Oikawa T, Nonaka T, Iwatsubo T, Hisanaga S, Goedert M, Hasegawa M. Small molecule inhibitors of alpha-synuclein filament assembly. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6085–6094. doi: 10.1021/bi0600749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Weber GA, Zheng J, Gendelman HE, Ikezu T. C1q-calreticulin induced oxidative neurotoxicity: relevance for the neuropathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;135:62–71. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikezu T, Luo X, Weber GA, Zhao J, McCabe L, Buescher JL, Ghorpade A, Zheng J, Xiong H. Amyloid precursor protein-processing products affect mononuclear phagocyte activation: pathways for sAPP- and Abeta-mediated neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2003;85:925–934. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floden AM, Li S, Combs CK. Beta-amyloid-stimulated microglia induce neuron death via synergistic stimulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha and NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2566–2575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4998-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesuisse C, Martin LJ. Long-term culture of mouse cortical neurons as a model for neuronal development, aging, and death. J Neurobiol. 2002;51:9–23. doi: 10.1002/neu.10037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paresce DM, Chung H, Maxfield FR. Slow degradation of aggregates of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid beta-protein by microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29390–29397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris W, Mansourian S, Chang Y, Lindsley L, Eckman EA, Frosch MP, Eckman CB, Tanzi RE, Selkoe DJ, Guenette S. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4162–4167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Watanabe K, Sekiguchi M, Hosoki E, Kawashima-Morishima M, Lee HJ, Hama E, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Saido TC. Identification of the major Abeta1–42-degrading catabolic pathway in brain parenchyma: suppression leads to biochemical and pathological deposition. Nat Med. 2000;6:143–150. doi: 10.1038/72237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KR, Verina T, Cummins DJ, Du Y, Dodel RC, Saura J, Fishman CE, DeLong CA, Piccardo P, Petegnief V, Ghetti B, Paul SM. Apolipoprotein E is essential for amyloid deposition in the APP(V717F) transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15233–15238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski M, Pankiewicz J, Scholtzova H, Ripellino JA, Li Y, Schmidt SD, Mathews PM, Fryer JD, Holtzman DM, Sigurdsson EM, Wisniewski T. A synthetic peptide blocking the apolipoprotein E/beta-amyloid binding mitigates beta-amyloid toxicity and fibril formation in vitro and reduces beta-amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:937–948. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63355-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda L, Cassatella MA, Szendrei GI, Otvos L, Jr, Baron P, Villalba M, Ferrari D, Rossi F. Activation of microglial cells by β-amyloid protein and interferon-γ. Nature. 1995;374:647–650. doi: 10.1038/374647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda L, Baron P, Prat E, Scarpini E, Scarlato G, Cassatella MA, Rossi F. Proinflammatory profile of cytokine production by human monocytes and murine microglia stimulated with beta-amyloid[25-35]. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;93:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossner S, Apelt J, Schliebs R, Perez-Polo JR, Bigl V. Neuronal and glial beta-secretase (BACE) protein expression in transgenic Tg2576 mice with amyloid plaque pathology. J Neurosci Res. 2001;64:437–446. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlage-Rübsamen M, Zeitschel U, Apelt J, Gartner U, Franke H, Stahl T, Gunther A, Schliebs R, Penkowa M, Bigl V, Rossner S. Astrocytic expression of the Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase (BACE1) is stimulus-dependent. Glia. 2003;41:169–179. doi: 10.1002/glia.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong HS, Hwang EM, Sim HJ, Cho HJ, Boo JH, Oh SS, Kim SU, Mook-Jung I. Interferon gamma stimulates beta-secretase expression and sAPPbeta production in astrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:922–927. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q, Zhang J, Liu H, Babu-Khan S, Vassar R, Biere AL, Citron M, Landreth G. Anti-inflammatory drug therapy alters beta-amyloid processing and deposition in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7504–7509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07504.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim GP, Yang F, Chu T, Chen P, Beech W, Teter B, Tran T, Ubeda O, Ashe KH, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Ibuprofen suppresses plaque pathology and inflammation in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5709–5714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillit H, Ding WH, Buee L, Kalman J, Altstiel L, Lawlor B, Wolf-Klein G. Elevated circulating tumor necrosis factor levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129:318–320. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90490-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowski E, Blennow K, Wallin A, Tarkowski A. Intracerebral production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, a local neuroprotective agent, in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:223–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1020568013953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasko I, Marx F, Steiner E, Hartmann T, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. TNFalpha plus IFNgamma induce the production of Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptides and decrease the secretion of APPs. FASEB J. 1999;13:63–68. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasko I, Veerhuis R, Stampfer-Kountchev M, Saurwein-Teissl M, Eikelenboom P, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Costimulatory effects of interferon-gamma and interleukin-1beta or tumor necrosis factor alpha on the synthesis of Abeta1-40 and Abeta1–42 by human astrocytes. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:682–689. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YF, Wang BJ, Cheng HT, Kuo LH, Wolfe MS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and interferon-gamma stimulate gamma-secretase-mediated cleavage of amyloid precursor protein through a JNK-dependent MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49523–49532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto H, Cheung BS, Hyman BT, Irizarry MC. Beta-secretase protein and activity are increased in the neocortex in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1381–1389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.9.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Lindholm K, Yang LB, Yue X, Citron M, Yan R, Beach T, Sue L, Sabbagh M, Cai H, Wong P, Price D, Shen Y. Amyloid beta peptide load is correlated with increased beta-secretase activity in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3632–3637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0205689101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LB, Lindholm K, Yan R, Citron M, Xia W, Yang XL, Beach T, Sue L, Wong P, Price D, Li R, Shen Y. Elevated beta-secretase expression and enzymatic activity detected in sporadic Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:3–4. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Sastre M, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Dewachter I, Walter J, Klockgether T, Van Leuven F. Focal glial activation coincides with increased BACE1 activation and precedes amyloid plaque deposition in APP[V717I] transgenic mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:22. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambamurti K, Kinsey R, Maloney B, Ge YW, Lahiri DK. Gene structure and organization of the human beta-secretase (BACE) promoter. FASEB J. 2004;18:1034–1036. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1378fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsonego A, Imitola J, Petrovic S, Zota V, Nemirovsky A, Baron R, Fisher Y, Owens T, Weiner HL. Abeta-induced meningoencephalitis is IFN-gamma-dependent and is associated with T cell-dependent clearance of Abeta in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5048–5053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506209103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.