Abstract

Ischemia/reperfusion injury is a major cause of the highly dysfunctional rate observed in marginal steatotic orthotopic liver transplantation. In this study, we document that the interactions between fibronectin, a key extracellular matrix protein, and its integrin receptor α4β1, expressed on leukocytes, specifically up-regulated the expression and activation of metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9, gelatinase B) in a well-established steatotic rat liver model of ex vivo ice-cold ischemia followed by isotransplantation. The presence of the active form of MMP-9 was accompanied by massive intragraft leukocyte infiltration, high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, and impaired liver function. Interestingly, MMP-9 activity in steatotic liver grafts was, to a certain extent, independent of the expression of its natural inhibitor, the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1. Moreover, the blockade of fibronectin-α4β1-integrin interactions inhibited the expression/activation of MMP-9 in steatotic orthotopic liver transplantations without significantly affecting the expression of metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2, gelatinase A). Finally, we identified T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages as major sources of MMP-9 in steatotic liver grafts. Hence, these findings reveal a novel aspect of the function of fibronectin-α4β1 integrin interactions that holds significance for the successful use of marginal steatotic livers in transplantation.

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is an effective therapeutic modality for end-stage liver disease. The critical shortage of human donor livers has provided the rationale to identify methods that would allow successful utilization of marginal steatotic donor grafts, which are characterized by higher dysfunction rate compared with nonsteatotic OLTs.1,2

Ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) insult, an antigen-independent event associated with leukocyte adhesion/migration and release of cytokines and free radicals, plays a major role in post-I/R organ injury suffered by OLTs.3,4 Leukocyte recruitment to sites of inflammatory stimulation in liver, which is a venous-driven vascular bed with slow flow rates, is poorly understood and may require distinct cascade of adhesive events compared with other organs with higher flow rates. Fibronectin (FN), a large glycoprotein with a central role in cellular adhesion and migration, is likely a key extracellular matrix (ECM) protein involved in these events.5

The role of FN in leukocyte adhesion, migration, and activation has been extensively reported.6–8 Moreover, we have previously shown that the so-called cellular FN, which is the most potent form of FN in promoting cell spreading and migration,9,10 is virtually absent in naïve steatotic livers, and it is expressed very early on the sinusoidal endothelium during cold ischemia, before steatotic OLT and leukocyte recruitment at the graft site.11

Leukocyte transmigration across endothelial and ECM barriers is dependent on both adhesive and focal matrix degradation mechanisms.12 The matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family, which comprises more than 24 well-characterized proteolytic enzymes, plays key roles in the responses of cells to their microenvironment.13 Of the MMPs, a specific subset, the gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), which are characterized by fibronectin-like domain of three type II repeats, are responsible for the turnover and degradation of several ECM proteins, including FN and type IV collagen, the major component of basement membranes.14,15 Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence that gelatinases play important functions in processes requiring basement membrane disruption, such as tumor invasion and arthritis16–19; therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that gelatinases may have an important function in leukocyte recruitment at the graft site.

We have previously shown that blockade of the interactions between FN and the integrin α4β1, the integrin receptor expressed on leukocytes, profoundly improved liver function and recipient survival of steatotic OLTs.11 The present study shows that MMP-9 is a novel identified player in steatotic OLT and that FN-α4β1 interactions regulate its expression by infiltrating leukocytes.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Grafting Techniques

Genetically obese (fa−/fa−) male Zucker (230–275 g), lean (fa/−) Zucker (260–300 g), and male Sprague Dawley (250–300 g) rats were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Syngeneic OLTs were performed using steatotic and nonsteatotic livers that were harvested from obese Zucker and from normal Sprague Dawley rats, respectively. Steatotic and lean livers were then stored at 4°C in UW solution for 4 and 24 hours, respectively, before being isotransplanted into lean Zucker or Sprague Dawley recipients. The standard techniques of liver harvesting and orthotopic transplantation without hepatic artery reconstruction were performed according to the previously described Kamada’s cuff technique and an anhepatic phase of ∼16 to 20 minutes.20,21 Animals were fed a standard rodent diet, with water ad libitum, and cared for according to guidelines approved by the American Association of Laboratory Animal Care. Blood was collected for serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) levels. Oil red O staining confirmed the high content of fat in the steatotic donor livers, and fatty Zucker rats of 230 to 275 g body weight have >30% (≅40%) liver steatosis, which sets them as marginal donors.

Treatment with CS1 Peptides

CS1 peptides were synthesized on a Beckman System 990 peptide synthesizer (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA) and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography, as described.22 The sequence of the peptides used in the study corresponded to the alternatively spliced CS1 variant of FN (25 mer: DELPQLVTLPHPNLHGPEILDVPST) and has been shown in vitro and in vivo to block the interaction between α4β1 integrin and its FN ligand.23–26 CS1 peptides (500 μg/rat) were administered to livers intraportally during procurement and before OLT. In addition, OLT recipients received a 3-day course of CS1 peptides (1 mg/rat/day, i.v.) and were followed for survival and SGOT levels. Control recipients received scrambled peptides or remained untreated. The chosen therapeutic regimen was based on previous work, in which CS1 peptide therapy improved function/histological preservation of steatotic liver grafts and prolonged their 14-day survival in lean recipients from 40% in control to 100% in CS1-treated OLTs.11

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Liver specimens were fixed in a 10% buffered formalin solution and embedded in paraffin. Sections were made at 4 μm and stained with H&E or Masson’s trichrome. The previously published Suzuki’s criteria27 were modified to reflect the histological severity of I/R injury in our OLT model. In this classification, sinusoidal congestion, hepatocyte necrosis, and ballooning degeneration are graded from 0 to 4.11 The absence of necrosis, congestion, or centrilobular ballooning is given a score of 0, whereas severe congestion, ballooning degeneration as well as >60% lobular necrosis is given a value of 4.

OLTs were also examined serially by immunohistochemistry for mononuclear cell infiltrate, activation, and MMP detection.28 In brief, liver tissue was embedded in Tissue Tec OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. Cryostat sections (5 μm) were fixed in acetone, and then endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited with 0.3% H2O2 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Appropriate primary mouse antibodies against rat T cells (R73), monocyte/macrophages (ED1), IL-2R+ cells (CD25) (Harlan Bioproducts, Indianapolis, IN), cellular FN (IST-9) (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY), metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2, gelatinase A), and metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9, gelatinase B) (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA; Oncogene, San Diego, CA; and EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA) were added at optimal dilutions. Bound primary antibody (Ab) was detected using biotinylated anti-mouse IgG or biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and streptavidin peroxidase-conjugated complexes (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Negative controls included sections in which the primary Ab was replaced with either dilution buffer or normal mouse or rabbit serum. Control sections from inflammatory tissues known to be positive for each stain were included as positive controls. The peroxidase reaction was developed with 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Dual immunostaining was performed by confirming peroxidase-based immunostaining for cellular markers with alkaline phosphatase-based immunohistochemistry for MMP-9. The alkaline phosphatase reaction was developed using the Vector Red Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories). The sections were evaluated blindly by counting the labeled cells in triplicates within 10 high-power fields per section. In the case of continuous labeling, some antigens were analyzed in a semiquantitative fashion where the relative abundance of each one was judged as negative [−, little (+), moderately abundant (++), or very abundant (+++, >200 cells/10 high-power fields].

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

For evaluation of cytokine and metalloproteinase gene expression, OLTs were harvested serially, and RNA was extracted with Trizol (Life Technologies Inc., Grand Island, NY) using a Polytron RT-3000 (Kinematica AG, Littau-Luzem, Switzerland) as previously described.30 Reverse transcription was performed using 4 μg of total RNA in a first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction with SuperScript II RNaseH reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies Inc.) as recommended by the manufacturer. The cDNA product was amplified by PCR using primers specific for rat cytokines and β-actin as previously described29 or for rat MMP-9, MMP-2, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1, and TIMP-2, which were obtained from BIOMOL Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Relative quantities of mRNA were determined using a densitometer (Kodak Digital Science 1D Analysis Software, Rochester, NY).

Western Blot and Zymography Analyses

Snap-frozen liver tissue was immediately homogenized as previously described.11 Protein content was determined by a colorimetric assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

For the Western blots, 50 μg of protein in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-loading buffer were electrophoresed through 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The gels were then stained with Coomassie blue to document equal protein loading. The membranes were blocked with 3% dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 (USB, Cleveland, OH) in PBS and incubated with specific primary antibodies against MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2, which were purchased from two different companies (BIOMOL and NeoMarkers). The filters were washed and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). After development, membranes were stripped and reblotted with an antibody against actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Relative quantities of protein were determined using a densitometer (Kodak Digital Science 1D Analysis Software).

Gelatinolytic activity was detected in liver extracts at a final protein content of 50 μg by 10% SDS-PAGE contained 1 mg/ml gelatin (Bio-Rad) under nonreducing conditions. After SDS-PAGE, the gels were washed twice in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes each time, rinsed in water, and incubated overnight in a development buffer at 37°C (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 5 mmol/L CaCl2, and 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.5). The gels were then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Bio-Rad) and destained with methanol/acetic acid/water (20:10:70). A clear zone indicates the presence of enzymatic activity. Positive controls for MMP-2 and MMP-9 (BIOMOL) and prestained molecular weight markers (Kaleidoscope Prestained Standards; Bio-Rad) served as standards. Relative quantities of protein were determined using a densitometer (Kodak Digital Science 1D Analysis Software).

Cell Culture

Murine macrophages (RAW 267) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC/TIB-71; Manassas, VA) and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with l-glutamine (ATCC/30-2002), 10% heat-inactivated serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C, 5% CO2. RAW 264.7 cells were subcultured every 2 to 3 days when they achieved 70 to 80% confluence, at which point they were passed 1:3 to 1:6. Cells suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium at passage 4 and at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml were cultured on FN (Biocoat; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or polylysine-coated plates. RAW cells were placed on 24-well coated plates at 5 × 106 cells/well and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for either 6 or 18 hours. For blocking experiments, cells were preincubated in suspension with two independent anti-α4 antibodies, clones PS/2 (IgG2b; ATCC), and (R1-2; eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes at 37°C before being cultured on FN-coated plates. Control rat IgG was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). In some experiments, FN-coated wells were pretreated with anti-FN antibody (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA) for 30 minutes at 37°C, and unbound antibodies were removed by washes in PBS before the addition of untreated RAW 264.7 cells. Cell viability was always confirmed by trypan blue exclusion. Cells and supernatants were collected for RT-PCR and zymography analyses, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

Data are shown as means ± SD. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed by Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and Student’s t-test when data had a normal distribution. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

CS1-Facilitated Blockade of FN-α4β1 Interactions Improved Liver Histological Preservation and Function of Steatotic OLTs

Our earlier studies have shown that cellular FN expression is virtually absent in naïve steatotic livers, and it is up-regulated in the liver vasculature after 4 hours of cold storage in UW solution before liver transplantation.11 Moreover, CS1 peptide therapy improved both function/histological preservation of steatotic liver grafts and recipient survival from 40% in controls to 100% in CS1-treated OLTs.11 The present study confirms and extends our previous observations on the beneficial role of CS1 peptide-mediated blockade of FN-α4β1 interactions. Indeed, CS1 peptide therapy improved liver function compared with respective controls; SGOT levels (IU/l) were 1667 ± 186 versus 2543 ± 352, P < 0.04 at day 1, and 155 ± 57 versus 1300 ± 180, P < 0.04 at day 7 (n = 6/group). Moreover, as we have previously shown,11 CS1 peptide-treated livers at day 1 showed good histological preservation with only mild signs of periportal ballooning or vascular congestion, contrasting with severally damaged controls, which were characterized by disruption of lobular architecture, significant periportal edema, marked leukocyte infiltration, vascular congestion, and necrosis.

CS1-Mediated Blockade of FN-α4β1 Interactions Selectively Down-Regulates MMP-9 Expression in Steatotic OLTs

Leukocyte migration across endothelial or ECM barriers is dependent on a coordinated series of adhesion release steps and focal matrix degradation.30 Gelatinases are metalloproteinases known to promote the breakdown of several matrix proteins, including FN31; thus, to determine whether CS1-facilitated blockade of α4β1-FN interactions affects gelatinase expression, steatotic liver grafts were sequentially harvested from CS1 peptide-treated and control OLTs and analyzed at mRNA and protein levels for MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression.

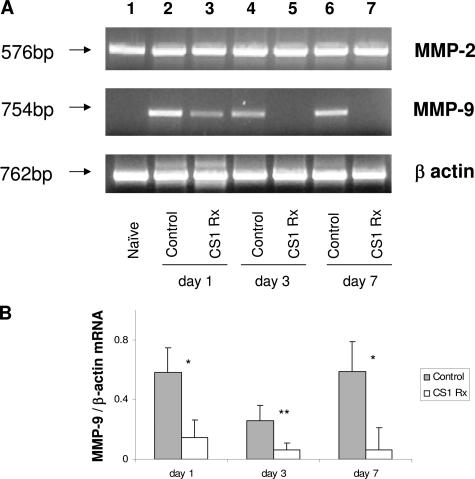

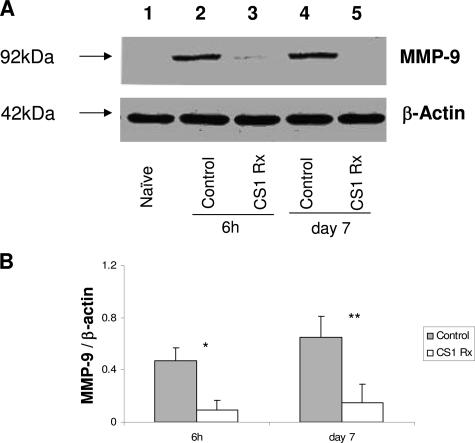

MMP-2 was highly expressed at mRNA level in naïve steatotic livers, and its expression was virtually unchanged after transplantation in both CS1 and control OLTs (Figure 1). On the other hand, MMP-9 mRNA expression was found virtually absent in naïve steatotic livers, scarcely detectable in CS1-treated OLTs, and highly present in control OLTs (Figure 1). Indeed, CS1-targeted therapy decreased liver MMP-9 mRNA expression by 4- to 10-fold compared with respective controls. These observations were correlated at protein level by Western blots; in fact, the lack of and modest levels of MMP-9 protein deposition characterized naïve steatotic livers and CS1 peptide-treated livers, respectively (Figure 2). In contrast, MMP-9 was readily detected at protein levels in control OLTs, and its expression appeared as early as 6 hours. Indeed, with the exception of day 3, in which we were unable to detect the 92-kd (proenzyme) band corresponding to MMP-9 in both CS1 peptide and control OLTs, the densitometric ratios of MMP-9 (92 kd)/β-actin were significantly depressed in CS1-treated livers compared with respective controls at 6 hours (0.09 ± 0.08 versus 0.47 ± 0.10, P < 0.001), 24 hours (0.20 ± 0.14 versus 0.41 ± 0.16, P < 0.01), and day 7 (0.15 ± 0.11 versus 0.65 ± 0.22, P < 0.01) after transplantation (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA expression in steatotic livers. A: MMP-2 mRNA expression was found relatively undisturbed in all studied groups at day 1 (lanes 2 and 3), day 3 (lanes 4 and 5), and day 7 (lanes 6 and 7) post-OLT, including naïve steatotic livers (lane 1). On the contrary, MMP-9 mRNA expression, which was virtually absent in naïve steatotic livers (lane 1), was found highly expressed in control steatotic OLTs (lanes 2, 4, and 6) and only slightly expressed in CS1-treated OLTs (lanes 3, 5, and 7). B: Densitometric analyses showed that MMP-9 mRNA expression was decreased by 4- to 10-fold in CS1 peptide-treated OLTs compared with respective controls. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5/group, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.02).

Figure 2.

MMP-9 expression in steatotic OLTs. A: Western blot analysis of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs. MMP-9 protein levels were readily detectable in control livers as early as 6 hours post-OLT (lane 2), and this expression was sustained in day 7 control OLTs (lane 4). In contrast, CS1 peptide-treated OLTs were characterized by a significant reduction in MMP-9 protein levels at both 6 hours (lane 3) and day 7 (lane 5) post-transplantation. Naïve steatotic livers (lane 1) showed undetectable levels of MMP-9 protein. B: Densitometric analyses showed that MMP-9 expression at protein level in CS1-treated OLTs was significantly reduced compared with respective controls. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5/group, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001).

CS1-Mediated Blockade of FN-α4β1 Interactions Down-Regulates MMP-9 Expression in Cold Lean Liver I/R Injury

To evaluate the efficacy of CS1 peptide therapy on down-regulation of MMP-9 expression in an alternate model of lean liver I/R injury, we performed OLTs using livers that were harvested from non-steatotic Sprague Dawley donors, stored at 4°C for 24 hours, and then transplanted into syngeneic recipients. In this well-established model of lean liver I/R injury, CS1 peptide-treated Sprague Dawley recipients had a 14-day survival rate of 100%, contrasting with a 50% survival rate observed in the respective controls.11 CS1 peptide-treated OLTs, at 24 hours after transplantation, showed significantly lower levels of MMP-9 mRNA expression as compared with respective controls (MMP-9/β-actin mRNA (0.33 ± 0.19 versus 1.13 ± 0.22, P < 0.005, n = 4/group). In contrast, MMP-2 mRNA expression was comparable in both CS1 peptide and control OLTs. These results indicate that CS1-mediated therapy specifically down-regulated MMP-9 in lean OLTs, and this mechanism may have a broad application to the overall outcome of liver transplantation.

CS1 Peptide Therapy Inhibits MMP-9 Activation and Prevents Massive Cellular Infiltration and Cytokine Release in Steatotic OLTs

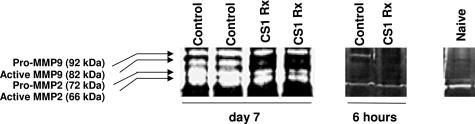

MMP-9 exists in two forms, pro-MMP-9 (proenzyme ∼92 kd) and so-called active MMP-9 (∼82 kd). We performed zymography analyses of naïve steatotic livers and steatotic liver transplants using SDS-PAGE/gelatin gels to access enzymatic activity in the liver specimens. As shown in Figure 4, MMP-9 activity is almost undetectable in naïve steatotic livers and is detected in modest levels in CS1 peptide-treated OLTs. On the other hand, control OLTs expressed considerably higher levels of MMP-9 activity (Figure 3), comparable with observations at mRNA and protein levels. MMP-9 was particularly very active in control OLTs at day 7 after transplantation and was characterized by the presence of both pro-MMP-9 and MMP-9 forms (Figure 3).

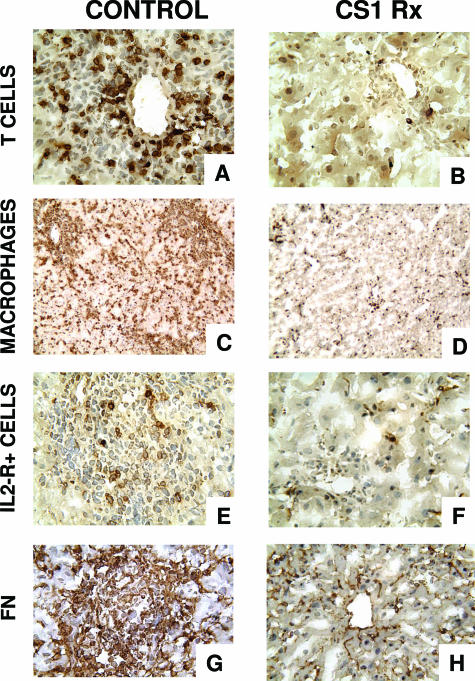

Figure 4.

Mononuclear cell infiltration/activation and fibronectin deposition in steatotic OLTs. Immunoperoxidase staining of T lymphocytes (A, B), monocyte/macrophages (C, D), IL-2R+ cells (E, F), and cellular FN (G, H) in fatty liver grafts at day 7 post-OLT. Blockade of the α4β1-FN interactions (B, D, F, H) was associated with significant decrease in intragraft infiltration of T lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and IL-2R+ cells and lower levels of FN expression compared with respective control OLTs (A, C, E, G), which were characterized by massive leukocyte infiltration/activation and FN deposition. Original magnification: ×200 (A, B, E–H); ×100 (C, D) (n = 5/group).

Figure 3.

Representative gelatin zymography of steatotic OLTs. Detection of gelatinase activity in steatotic livers indicated that CS1 peptide-treated OLTs expressed much lower levels of MMP-9 activity as compared with respective controls. In addition, the active form of MMP-9, which was virtually undetectable in CS1-treated OLTs and naïve steatotic livers, was highly expressed in control livers at day 7 post-OLT 9 (n = 3–4/group).

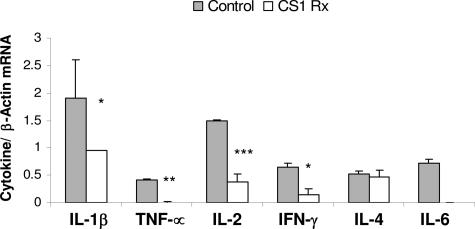

Interestingly, the presence of the active form of MMP-9 (82 kd) in the day 7 control OLTs was highly correlated, with massive leukocyte infiltration observed in these grafts (Figure 4). CS1-treated OLTs, which lacked the expression this form of MMP-9, showed only mild leukocyte infiltration (Figure 4). Although a significant difference in myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (3.09 ± 0.78 versus 4.29 ± 0.5), an index of neutrophil infiltration, was not found, T cells (10 ± 3 versus 56 ± 20, P < 0.03) and macrophages (87 ± 23 versus >200) were profoundly depressed in the CS1 peptide-treated group compared with the respective controls at day 7 post-OLT. The intragraft expression of cellular FN was markedly reduced in the 7-day CS1 peptide-treated OLTs compared with the respective control liver grafts (Figure 4). Moreover, the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines, at mRNA level, such as interleukin (IL)-1β (0.95 ± 0.01 versus 1.90 ± 0.70, P < 0.04), tumor necrosis factor-α (0.01 ± 0.01 versus 0.41 ± 0.03, P < 0.001), IL-2 (0.38 ± 0.14 versus ± 0.01, P < 0.004), interferon-γ (0.15 ± 0.21 versus 0.65 ± 0.07, P < 0.04), and IL-6 (not detectable versus 0.71 ± 0.08) was also profoundly depressed in the CS1 peptide-treated OLTs compared with respective controls (Figure 5). Significant differences on IL-4 mRNA (0.47 ± 0.12 versus 0.52 ± 0.06) expression between treated and respective control OLTs were not observed (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in steatotic OLTs. Proinflammatory IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-2, interferon (IFN)-γ, and IL-6 expression was profoundly depressed in CS1-treated livers compared with respective controls at day 7 post-OLT. *P < 0.04, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.004 (n = 4/group).

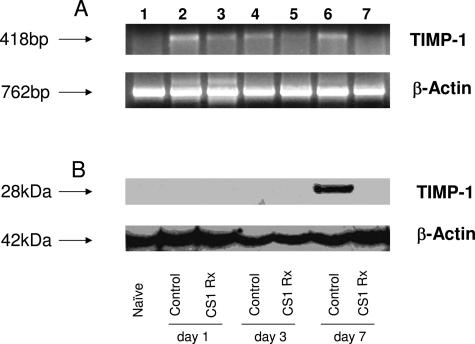

MMP-9 Activity Is Resistant to TIMP-1 Inhibition in Steatotic OLTs

TIMP-1 is a natural inhibitor of MMP-9.32 TIMPs suppress protease activity by forming high-affinity, 1:1 stoichiometric, noncovalent complexes with the active MMPs.33 In addition to binding to the active form of MMP-9, TIMP-1 can also form complexes with pro-MMP-9.34 To unveil a possible link between our previous results on MMP-9 activation and the presence/absence of TIMP-1 in steatotic OLTs, we evaluated TIMP-1 expression at both mRNA and protein levels in our experimental settings. At mRNA level, TIMP-1 was modestly and mildly expressed in control and CS1-treated OLTs, respectively (Figure 6A). At protein level, TIMP-1 was virtually undetectable in 6-hour (not shown), day 1, and day 3 CS1 peptide-treated and control OLTs. The near absence of TIMP-1 expression was also observed in day 7 CS1 peptide-treated OLTs, contrasting with the respective controls, in which TIMP-1 was readily detected (P < 0.001) (Figure 6B). The paradoxical availability of TIMP-1 deposition at protein level in control steatotic OLTs at day 7, which were characterized by high levels of MMP-9 activity (Figure 3), suggests that MMP-9 expressed by steatotic liver grafts is somehow resistant to TIMP-1 inactivation. Moreover, it suggests that the function of TIMP-1 in steatotic OLTs can be distinct from the classic concept that TIMP-1 regulates physiological or pathological processes through its ability to inhibit MMPs. A comparable situation has been observed in cancer patients, in which high levels of TIMP-1 were associated with poor patient prognosis.35

Figure 6.

TIMP-1 detection in steatotic OLTs. Top panel illustrates TIMP-1 expression at mRNA level (A) in steatotic naïve livers (lane 1), and OLTs at day 1 (lanes 2 and 3), day 3 (lanes 4 and 5), and day 7 (lanes 6 and 7) after transplantation. Control livers (lanes 2, 4, and 6) showed higher levels of TIMP-1 mRNA expression in particular at days 1 and 7 post-OLT (lanes 2 and 6) compared with CS1-treated OLTs (lanes 3, 4, and 5). However, at protein level (B, bottom panel), TIMP-1 was virtually undetectable in steatotic livers with the exception of day 7 control OLTs (lane 6), which expressed relatively high levels of TIMP-1 (n = 4/group).

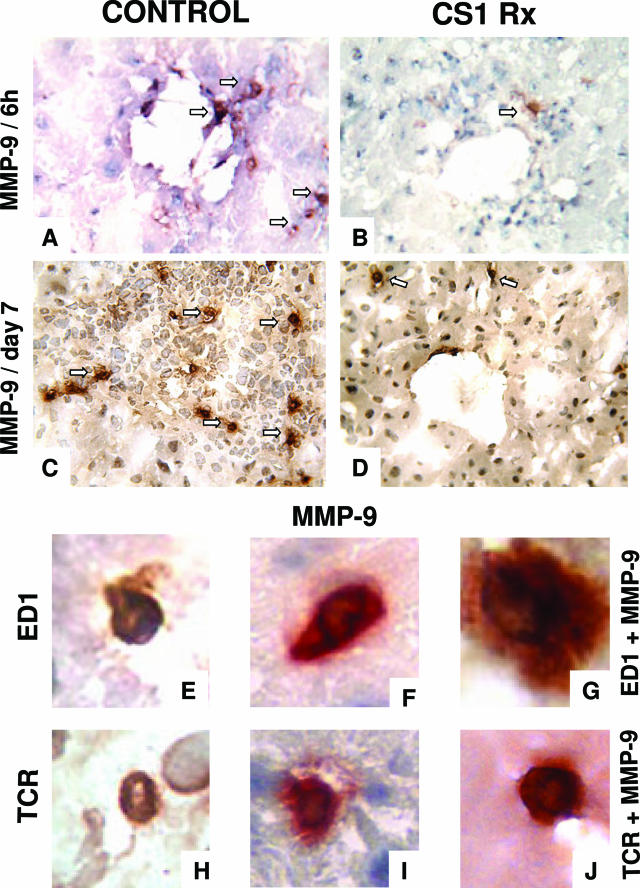

Macrophages and T Cells Are Sources of Inducible MMP-9 in Steatotic OLTs

To identify the sources of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs, we performed immunohistological analyses in serial cryostat sections of CS1 peptide-treated and control grafts. MMP-9+ labeling was detected in perivascular areas as early as 6 hours after transplantation in membranes of infiltrating leukocytes. As shown in Figure 7, CS1 peptide-treated OLTs were characterized by small numbers of MMP-9+ cells compared with respective controls at 6 hours (5 ± 3 versus 15 ± 5, P < 0.004) and 7 days (11 ± 4 versus 49 ± 10, P < 0.003) after transplantation. Most of the intragraft infiltrating MMP-9+ cells showed the convoluted nuclear morphology typical of macrophages. In addition, we also detected MMP-9+ cells with the round nuclear shape characteristic of lymphocytes. To further confirm our observations, we performed additional analyses at 6 hours and day 7 post-OLT by double immunostaining using distinct antibodies against leukocyte markers and against MMP-9 and two distinct colorimetric detection systems, peroxidase-DAB (brown) and phosphatase-Fast Red (red). As Figure 7 illustrates at high magnification, single antibody-stained infiltrating monocyte/macrophages/ED1+ or T lymphocyte/TCR+ cells were dyed in brown (Figure 7, E and H), and single antibody-stained infiltrating MMP-9+ cells were labeled in red (Figure 7, F and I). However, when cells were stained in separate tissue sections, with two primary antibodies against either combination ED1/MMP-9 (Figure 7G) or TCR/MMP-9 (Figure 7J), these cells stained in a reddish brown color, indicating co-cellular localization of both markers. Altogether, these studies show that infiltrating leukocytes, in particular monocyte/macrophages and T lymphocytes, were sources of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs.

Figure 7.

MMP-9+ cells in steatotic OLTs. Very few MMP-9+ infiltrating leukocytes were detected in CS1 peptide-treated livers (B and D) compared with respective control OLTs (A and C) at 6 hours (A and B) and day 7 (C and D) after transplantation. Arrows denote labeled cells. To confirm the sources of MMP-9 in steatotic liver grafts, single antibody-stained infiltrating monocyte/macrophages/ED1+ (E) or T lymphocyte/TCR+ cells (H) were stained brown, and single antibody-stained infiltrating MMP-9+ cells were labeled in red (F and I) in serial OLT sections. However, when cells were stained with two primary antibodies against either combination ED1/MMP-9 (G) or TCR/MMP-9 (J), these cells were stained a reddish brown color, which indicated co-cellular localization of both markers. Original magnification: ×200 (A–D); ×600 (E–J) (n = 3–5/group).

Fibronectin-α4β1 Interactions Specifically Up-Regulate MMP-9 Expression in RAW 264.7 Macrophage-Like Cells

To further support our previous in vivo observations, we performed cell culture experiments to assess whether FN can regulate metalloproteinase expression in vitro. We identified macrophages as major sources of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs; thus, we cultured RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells in FN-coated plates. The integrin receptor α4β1 is expressed in >80% of RAW 264.7 cells as evaluated by FACS (not shown). Therefore, we cultured RAW 264.7 cells on FN-coated plates in the absence or presence of antibodies against FN or α4 integrin. As shown in Figure 8, cultured macrophages in fibronectin-coated plates (lane 4) expressed higher levels of MMP-9 mRNA (≅3-fold increase) compared with the respective control cells cultured in polylysine-coated plates (lane 3). However, RAW cells cultured in FN-coated plates pretreated with anti-FN Ab (lane 5) or RAW cells incubated with an anti-α4 Ab (lane 6) before being plated on FN-coated plates showed significantly lower levels of MMP-9 expression, equivalent to MMP-9 levels observed in cells cultured on polylysine-coated plates. Control IgG had no effect on MMP-9 expression. In addition, in a similar fashion to what was observed at the mRNA level, MMP-9 activity was also particularly increased in supernatants from cells plated on FN in comparison with respective control cells plated on polylysine- or antibody-treated controls. Interestingly, MMP-2 mRNA expression was virtually undetectable in RAW 264.7 cells cultured in both polylysine and FN-coated plates (Figure 8A). Thus, these results support our in vivo observations that FN-integrin interactions specifically up-regulate MMP-9 expression by mononuclear cells.

Figure 8.

Gelatinase detection in RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells. A: Representative zymogram of RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells cultured on FN-coated plates (lane 4) expressed increased levels of MMP-9 mRNA compared with the respective control cells cultured in polylysine-coated plates (lane 3). In contrast, MMP-9 expression was significantly depressed in RAW cells cultured in FN-coated plates pretreated with anti-FN Ab (lane 5) or RAW cells incubated with an anti-α4 Ab (lane 6) before being plated on FN-coated plates. B: Densitometric ratios for MMP-9/β-actin mRNA were significantly increased in cells cultured on FN compared with cells cultured on polylysine, cells cultured on FN-coated plates pretreated with anti-FN Ab, and cells incubated with an anti-α4 Ab prior being plated on FN-coated plates (n = 4/group, *P < 0.05).

Discussion

This study provides new insights into the role of fibronectin in the pathophysiology of marginal steatotic OLTs. Our major findings are that 1) FN-α4β1 interactions up-regulated the expression and activation of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs; 2) blockade of FN-α4β1 interactions inhibited the expression/activation of MMP-9 without significantly affecting MMP-2 expression in both steatotic and normal OLTs; 3) expression of the active form of MMP-9 was accompanied by massive leukocyte infiltration, extensive FN deposition, and proinflammatory cytokine release in steatotic liver grafts; 4) MMP-9 activation was, to a certain extent, independent of TIMP-1 expression; and 5) infiltrating leukocytes were the sources of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs.

Ischemic damage in the liver associated with leukocyte adhesion/migration and release of cytokines and free radicals plays a major role in post-I/R organ injury, leading to a decline of liver function and to a potential increase in organ immunogenicity, which can result in graft loss.36 The mechanisms involved in leukocyte recruitment to sites of inflammatory stimulation in liver are far from being entirely understood. In general, leukocyte migration across endothelial barriers or ECM proteins is dependent on a coordinated series of adhesion release steps and focal matrix degradation.30 However, leukocyte recruitment to an organ transplant may require a sequential cascade of adhesive and de-adhesive events that are particular to the type of transplanted organ. FN has been well characterized as an ECM glycoprotein that can regulate many cellular functions, including cellular adhesion and migration.37,38

FN can be subdivided into two forms, the soluble plasma FN and the less soluble cellular FN. The plasma FN that circulates in blood is in a closed, allegedly nonactive form, and most of the FN activities in the body have been attributed to the insoluble form of FN, which exists as part of the extracellular matrix.10,37 Cellular FN, which is mostly absent in normal adult tissues, is present in several matrices under tissue pathological conditions, including organ transplantation.28 A role for FN-mediated leukocyte migration has been previously shown by others in skin inflammation,39 rheumatoid arthritis,40 diabetes41,42 and by us in cardiac transplants.8 Cellular FN is expressed by sinusoidal endothelial cells very early after liver injury.43

We have shown that cellular FN was detected in the sinusoidal endothelium after cold storage and immediately before liver transplantation, preceding leukocyte recruitment to the graft.11 In the present study, we showed that FN-α4β1 integrin interactions selectively up-regulated the expression of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs and that this mechanism may have a broad application to cold liver I/R injury. Indeed, FN-α4β1 integrin interactions up-regulated MMP-9 expression in an experimental model of normal lean OLTs as well. Moreover, we identified infiltrating leukocytes as sources of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs. Within the leukocytes, monocytes/macrophages and T lymphocytes were found to be major sources of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs, in particular at 7 days after transplantation. In addition to mononuclear leukocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes are also possible sources of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs. Neutrophils, thought for many years to express only β2 integrins, use β1 integrins for migration into tissues44; of the β1 integrins, α4 seems to have a critical role in neutrophil adhesion and migration.45 Interestingly, neutrophils are able to migrate on FN and incapable of significant migration on VCAM-1.46 The lack of a suitable antibody to detect rat neutrophils precluded us from detecting them by immunostaining; however, MPO activity, an index of neutrophil infiltration, and naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase assays indicated that neutrophil infiltration was rather modest in steatotic OLTs, and it occurred predominantly during the first 24 hours after transplantation.11 MPO activity in liver grafts decreased progressively after 24 hours of transplantation and by day 7 was not significantly different between CS1 peptide-treated and control livers. In contrast, mononuclear cell infiltration and MMP-9+ leukocytes were significantly increased in day 7 control OLTs as compared with the CS1 peptide-treated liver grafts. Therefore, neutrophils may also contribute to a certain degree to the MMP-9 expression detected in steatotic OLTs during the first hours after transplantation; they do not seem to represent a major source of this enzyme in long-term OLTs. Furthermore, these observations were supported by in vitro experiments in which mononuclear cells cultured on FN expressed higher levels of MMP-9, and disruption of cell adhesion to FN, with either anti-FN antibodies or anti-α4β1 antibodies, significantly lowered the levels of MMP-9 expressed by the cultured macrophages.

MMP-9 expression has been related to several pathological conditions, including liver diseases. Indeed, a correlation has been established between disease severity/progression and MMP-9 detection in the serum of patients with various types of liver injury, including I/R injury,47 acute allograft rejection,48 and chronic viral hepatitis.49 Our preliminary results in MMP-9(−/−) deficient mice showed significantly improved liver function after ischemic damage and also support a critical role for MMP-9 in the pathogenesis of liver I/R injury (A.J. Coito, unpublished observations).

Matrix degradation is essential to leukocyte migration across ECM proteins, not only by facilitating “matrix permeability,” but also by generating ECM-derived fragments, which are biologically active and can be highly chemotactic for leukocytes.50 In our settings, the presence of the active form of MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs was correlated with massive leukocyte infiltration, suggesting a key role for MMP-9 on leukocyte recruitment at the graft site. That is further supported by observations in murine models of allergen-induced airway inflammation and zymosan peritonitis, which showed that MMP-9(−/−) mice had significantly less leukocyte infiltration compared with their corresponding wild-type littermates.51,52

In addition, MMP-9 has been implicated in release and activation of cytokines and growth factors. In an ovarian carcinoma model, MMP-9 and, to a lesser extent, MMP-2 are associated with increased bioavailability of VEGF.53 TGF-β, which is secreted in a latent complex where the cytokine noncovalently interacts with a latency-associated peptide (LAP), is proteolytically activated by MMP-9 in vitro.54

Interestingly, MMP-2 was expressed at almost constant levels in all studied groups, including naïve fatty livers, contrasting with MMP-9 expression and indicating that FN-α4β1 interactions do not affect MMP-2 expression. Indeed, macrophages virtually did not express MMP-2 in vitro, either in the presence or absence of FN. The observations indicating that FN-leukocyte interactions selectively up-regulated MMP-9 in steatotic OLTs are highlighted by observations that only MMP-9 seems to be involved in I/R injury during human liver transplantation.55

The role of MMP-2 expression in steatotic livers is far from being understood, and it may be associated to more than one function in OLTs. MMP-2 was expressed in naïve steatotic livers, which suggests that it may play a role in the normal liver physiology. In this regard, we have preliminary data in a mouse model of warm liver I/R injury, in which MMP-9(−/−) livers showed significant improved liver function as compared with MMP-9+/+ livers and with livers treated with an inhibitor that targets both MMP-2 and MMP-9 (A.J. Coito, unpublished observations). On the other hand, high levels of MMP-256 and steatosis57 have been linked to a high susceptibility of liver fibrosis, although the link between MMP-2 and fibrosis is likely not simple and may require the simultaneous presence of other profibrosis factors. Indeed, CS1-treated OLTs at day 7, which showed increased levels of MMP-2 activity (compared with naïve livers), were characterized by minimal levels of fibronectin deposition. In contrast, the respective control OLTs, which were also characterized by increased levels of MMP-2 activity, showed extensive intragraft fibronectin staining.

TIMP-1, the natural inhibitor of MMP-9,35 was up-regulated in control damaged steatotic OLTs, which were characterized by elevated levels of MMP-9 activity (proenzyme and enzyme) and by massive leukocyte infiltration. On the other hand, blockade of FN-α4β1 interactions depressed TIMP-1 expression and leukocyte infiltration in the liver grafts. These observations were somewhat unexpected, and they can perhaps be explained through the concept that balance between the levels of MMP and TIMP expression mediate the level of proteolysis by MMPs58; hence, the balance can still favor MMP-9 proteolysis in damaged steatotic OLTs, despite the up-regulation of TIMP-1. On the other hand, several lines of evidence indicate that TIMP-1 is a multifunctional protein with functions distinct from protease inhibition. For example, TIMP-1 can stimulate cell proliferation independently of its MMP inhibitory effect,59 raising the possibility that the pathophysiological role of TIMP-1 in steatotic OLTs may be unrelated to metalloproteinase inhibition. Further experimentation is required to test this hypothesis. Finally, it is also important to consider that protease inhibitors, present in extracellular spaces, can only confine the activity of leukocyte-derived proteinases to the immediate pericellular environment but cannot prevent degradation of proteins that are in close contact with the cells.32

In summary, our studies support the view that cell attachment to ECM proteins and subsequent degradation are related events. They emphasize an important function for FN-α4β1-integrin interactions in the development of I/R injury in steatotic liver grafts. Furthermore, the beneficial effect of FN-α4β1-integrin blockade involves several mechanisms, including selective inhibition of MMP-9 expression on leukocytes, which is likely a key factor in leukocyte-mediated matrix breakdown/transmigration and in amplification of the inflammatory response in steatotic OLTs. This work provides the rationale to identify therapeutic approaches based on novel concepts that would allow successful utilization of marginal steatotic grafts.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Ana J. Coito, Dumont-UCLA Transplant Center, Rm. 77-120 CHS, Box 957054, Los Angeles, CA 90095-7054. E-mail: acoito@mednet.ucla.edu.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI057832), the American Liver Foundation, and the Dumont Research Foundation.

References

- Alexander JW, Vaughn WK. The use of “marginal” donors for organ transplantation: the influence of donor age on outcome. Transplantation. 1991;51:135–141. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann TG, Wheeler MD, Schwabe RF, Connor HD, Schoonhoven R, Bunzendahl H, Brenner DA, Jude SR, Zhong Z, Thurman RG. Gene delivery of Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase improves graft function after transplantation of fatty livers in the rat. Hepatology. 2000;32:1255–1264. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koneru B, Dikdan G. Hepatic steatosis and liver transplantation current clinical and experimental perspectives. Transplantation. 2002;73:325–330. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200202150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasberg SM, Howard TK, Molmenti EP, Hertl M. Selecting the donor liver: risk factors for poor function after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;20:829–838. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, de Sousa M, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Fibronectin in immune responses in organ transplant recipients. Dev Immunol. 2000;7:239–248. doi: 10.1155/2000/98187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, van Seventer GA, Horgan KJ, Shaw S. Costimulation of proliferative responses of resting CD4+ T cells by the interaction of VLA-4 and VLA-5 with fibronectin or VLA-6 with laminin. J Immunol. 1990;145:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauzenberger D, Klominek J, Sundqvist KG. Functional specialization of fibronectin-binding β1-integrins in T lymphocyte migration. J Immunol. 1994;153:960–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, Binder J, Brown LF, de Sousa M, Van De WL, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Anti-TNF-α treatment down-regulates the expression of fibronectin and decreases cellular infiltration of cardiac allografts in rats. J Immunol. 1995;154:2949–2958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P, Culp LA. Adhesion activity in fibronectin’s alternatively spliced domain EDa (EIIIA): complementarity to plasma fibronectin functions. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:517–527. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe R, Oh-e N, Sekiguchi K. Alternatively spliced EDA segment regulates fibronectin-dependent cell cycle progression and mitogenic signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5919–5924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amersi F, Shen XD, Moore C, Melinek J, Busuttil RW, Kupiec Weglinski JW, Coito AJ. Fibronectin-α4β1 integrin-mediated blockade protects genetically fat Zucker rat livers from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1229–1239. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63919-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi E, Bender JR, Blasi F, Pardi R. Through and beyond the wall: late steps in leukocyte transendothelial migration. Immunol Today. 1997;18:586–591. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Murphy G. Matrix metalloproteinases at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4015–4016. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki T, Sato H, Furukawa M, Pagano JS. The expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 is enhanced by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3621–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Woessner JF., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, Vu TH, Itoh T, Tamaki K, Tanzawa K, Thorpe P, Itohara S, Werb Z, Hanahan D. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-β and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannelli G, Erriquez R, Iannone F, Marinosci F, Lapadula G, Antonaci S. MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Bonfil RD, Chinni S, Deng X, Trindade Filho JC, Bernardo M, Vaishampayan U, Che M, Sloane BF, Sheng S, Fridman R, Cher ML. Matrix metalloproteinase activity and osteoclasts in experimental prostate cancer bone metastasis tissue. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1173–1186. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada N, Calne RY. Orthotopic liver transplantation in the rat: technique using cuff for portal vein anastomosis and biliary drainage. Transplantation. 1979;28:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada N, Calne RY. A surgical experience with five hundred thirty liver transplants in the rat. Surgery. 1983;93:64–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, Onodera K, Kato H, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Fibronectin-mononuclear cell interactions regulate type 1 helper T cell cytokine network in tolerant transplant recipients. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1207–1218. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64636-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elices MJ, Osborn L, Takada Y, Crouse C, Luhowskyj S, Hemler ME, Lobb RR. VCAM-1 on activated endothelium interacts with the leukocyte integrin VLA-4 at a site distinct from the VLA-4/fibronectin binding site. Cell. 1990;60:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90661-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elices MJ, Tsai V, Strahl D, Goel AS, Tollefson V, Arrhenius T, Wayner EA, Gaeta FC, Fikes JD, Firestein GS. Expression and functional significance of alternatively spliced CS1 fibronectin in rheumatoid arthritis microvasculature. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:405–416. doi: 10.1172/JCI116975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarem R, Newham P, Askari JA, Green LJ, Clements J, Edwards M, Humphries MJ, Mould AP. Competitive binding of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and the HepII/IIICS domain of fibronectin to the integrin α4β1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4005–4011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl SM, Allen JB, Hines KL, Imamichi T, Wahl AM, Furcht LT, McCarthy JB. Synthetic fibronectin peptides suppress arthritis in rats by interrupting leukocyte adhesion and recruitment. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:655–662. doi: 10.1172/JCI117382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Toledo-Pereyra LH, Rodriguez FJ, Cejalvo D. Neutrophil infiltration as an important factor in liver ischemia and reperfusion injury: modulating effects of FK506 and cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1993;55:1265–1272. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, Brown LF, Peters JH, Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Van De WL. Expression of fibronectin splicing variants in organ transplantation: a differential pattern between rat cardiac allografts and isografts. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1757–1772. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, Shaw GD, Li J, Ke B, Ma J, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Selectin-mediated interactions regulate cytokine networks and macrophage heme oxygenase-1 induction in cardiac allograft recipients. Lab Invest. 2002;82:61–70. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum CB, Werb Z. Focalized proteolysis: spatial and temporal regulation of extracellular matrix degradation at the cell surface. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:731–738. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CA, Campbell EJ. The cell biology of leukocyte-mediated proteolysis. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:137–150. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function, and biochemistry. Circ Res. 2003;92:827–839. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070112.80711.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode W, Fernandez-Catalan C, Grams F, Gomis-Ruth FX, Nagase H, Tschesche H, Maskos K. Insights into MMP-TIMP interactions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;878:73–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MJ, McCarthy K. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer: prognostic markers and targets for therapy (review). Int J Oncol. 1998;12:1343–1348. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.6.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy K, Maguire T, McGreal G, McDermott E, O’Higgins N, Duffy MJ. High levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 predict poor outcome in patients with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:44–48. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990219)84:1<44::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja C, Prescott L, Koneru B. Critical preservation injury in rat fatty liver is to hepatocytes, not sinusoidal lining cells. Transplantation. 1998;65:167–172. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199801270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankov R, Yamada KM. Fibronectin at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3861–3863. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka-Patynowski I, Schwarzbauer JE. The ins and outs of fibronectin matrix assembly. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3269–3276. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TA, Mizutani H, Kupper TS. Two integrin-binding peptides abrogate T cell-mediated immune responses in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8072–8076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffón A, Garcia-Vicuna R, Humbria A, Postigo AA, Corbi AL, de Landazuri MO, Sanchez-Madrid F. Upregulated expression and function of VLA-4 fibronectin receptors on human activated T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:546–552. doi: 10.1172/JCI115338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geutskens SB, Nikolic T, Dardenne M, Leenen PJ, Savino W. Defective up-regulation of CD49d in final maturation of NOD mouse macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3465–3476. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geutskens SB, Mendes-da-Cruz DA, Dardenne M, Savino W. Fibronectin receptor defects in NOD mouse leucocytes: possible consequences for type 1 diabetes. Scand J Immunol. 2004;60:30–38. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarnagin WR, Rockey DC, Koteliansky VE, Wang SS, Bissell DM. Expression of variant fibronectins in wound healing: cellular source and biological activity of the EIIIA segment in rat hepatic fibrogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2037–2048. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werr J, Xie X, Hedqvist P, Ruoslahti E, Lindbom L. β1 integrins are critically involved in neutrophil locomotion in extravascular tissue in vivo. J Exp Med. 1998;187:2091–2096. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston B, Kubes P. The α4-integrin: an alternative pathway for neutrophil recruitment? Immunol Today. 1999;20:545–550. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit B, Colarusso P, Kubes P. Fundamentally different roles for LFA-1, Mac-1 and α4-integrin in neutrophil chemotaxis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5205–5220. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyvenhoven JP, Ringers J, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB, van Hoek B. Serum matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the late phase of ischemia and reperfusion injury in human orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:2967–2969. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyvenhoven JP, Verspaget HW, Gao Q, Ringers J, Smit VT, Lamers CB, van Hoek B. Assessment of serum matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 after human liver transplantation: increased serum MMP-9 level in acute rejection. Transplantation. 2004;77:1646–1652. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000131170.67671.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy V, Monier F, Bottari S, Trocme C, Sturm N, Hilleret MN, Morel F, Zarski JP. Circulating matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, 9 and their inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 as serum markers of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C: comparison with PIIINP and hyaluronic acid. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr KM, Kurth CA, Xie DL, Seyer JM, Homandberg GA. The amino-terminal 29- and 72-kd fragments of fibronectin mediate selective monocyte recruitment. Blood. 1990;76:2117–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo DD, Tournoy KG, Vermaelen K, Munaut C, Foidart JM, Louis R, Noel A, Pauwels RA. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency impairs cellular infiltration and bronchial hyperresponsiveness during allergen-induced airway inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:491–498. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64205-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaczkowska E, Chadzinska M, Scislowska-Czarnecka A, Plytycz B, Opdenakker G, Arnold B. Gelatinase B/matrix metalloproteinase-9 contributes to cellular infiltration in a murine model of zymosan peritonitis. Immunobiology. 2006;211:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belotti D, Paganoni P, Manenti L, Garofalo A, Marchini S, Taraboletti G, Giavazzi R. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP9 and MMP2) induce the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by ovarian carcinoma cells: implications for ascites formation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5224–5229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFβ activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:217–224. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyvenhoven JP, Molenaar IQ, Verspaget HW, Veldman MG, Palareti G, Legnani C, Moolenburgh SE, Terpstra OT, Lamers CB, van Hoek B, Porte RJ. Plasma MMP-2 and MMP-9 and their inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 during human orthotopic liver transplantation: the effect of aprotinin and the relation to ischemia/reperfusion injury. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:506–513. doi: 10.1160/TH03-05-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornek M, Raskopf E, Guetgemann I, Ocker M, Gerceker S, Gonzalez-Carmona MA, Rabe C, Sauerbruch T, Schmitz V. Combination of systemic thioacetamide (TAA) injections and ethanol feeding accelerates hepatic fibrosis in C3H/He mice and is associated with intrahepatic up regulation of MMP-2, VEGF and ICAM-1. J Hepatol. 2006;45:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaemers IC, Groen AK. New insights in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2006;17:268–273. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000226118.43178.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würtz SO, Schrohl AS, Sorensen NM, Lademann U, Christensen IJ, Mouridsen H, Brunner N. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:215–227. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]