Abstract

Objective

To estimate the rate of progression from newly acquired (incident) impaired fasting glucose (IFG) to diabetes under the old and new IFG criteria, and to identify predictors of progression to diabetes.

Research Design and Methods

We identified 5,452 members of an HMO with no prior history of diabetes, at least two elevated fasting glucose tests (100–125 mg/dl) measured between January 1, 1994 and December 31, 2003, and a normal fasting glucose test prior to the two elevated tests. All data were obtained from electronic records of routine clinical care. Subjects were followed until they developed diabetes, died, left the health plan, or until December 31, 2005.

Results

Overall, 8.1% of subjects whose initial abnormal fasting glucose was 100–109 mg/dl (Added IFG), and 24.3% of subjects whose initial abnormal fasting glucose was 110–125 mg/dl (Original IFG) developed diabetes (p<.0001). Added IFG subjects who progressed to diabetes did so within a mean of 41.4 months, a rate of 1.34% per year. Original IFG subjects converted at a rate of 5.56% per year after an average of 29.0 months. A steeper rate of increasing fasting glucose, higher body mass index, blood pressure and triglycerides, and lower HDL cholesterol predicted diabetes development.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, these are the first estimates of diabetes incidence from a clinical care setting when date of IFG onset is approximately known under the new criterion for IFG. The older criterion was more predictive of diabetes development. Many newly identified IFG patients progress to diabetes in less than three years, the currently recommended screening interval.

INTRODUCTION

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) defines Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG) as an intermediate state of hyperglycemia in which glucose levels do not meet criteria for diabetes, but are too high to be considered normal.1 Although the ADA calls IFG “pre-diabetes”,1 reported estimates of diabetes development in IFG patients vary widely.2 The Hoorn study found that 33% of patients with IFG but not Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) and 64.5% of patients with IFG and IGT developed diabetes over a follow-up of 5.8 to 6.5 years.3 The Paris Prospective Study reported much lower proportions—2.7% among patients with normal glucose tolerance or isolated IFG and 14.9% among patients with IFG and IGT over 30 months of follow-up.4 An Italian study spanning 11.5 years found that 9.1% of patients with isolated IFG and 44.4% of subjects with IFG and IGT developed diabetes.5 Studies of non-white populations have reported diabetes development proportions ranging from 21.6% over five years among Mauritians with isolated IFG,6 to 41.2% over five years among Pima Indians with IFG and IGT.7 The highest proportion of diabetes development, 72.7% over seven years among subjects with IGT and IFG, was found in a Brazilian-Japanese population.8

Most of this wide variation in reported rates of diabetes development among IFG patients probably arises from unknown time spent with IFG. To our knowledge, only one study to date has estimated the rate of progression from IFG to diabetes starting from incident “pre-diabetes”. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging found that diabetes occurred in 25% of 216 subjects over 10 years following their progression from normal glucose tolerance to IFG or IGT.9

After these studies had been published, the ADA lowered its criterion for IFG from 110 mg/dl to 100 mg/dl to optimize the sensitivity and specificity of IFG for predicting future diabetes.10 This decision generated some controversy because of the large proportion of the population that now meets the definition of IFG.11 To our knowledge, estimates of rates of diabetes progression among patients newly meeting this new criterion for IFG are not known. Therefore, we sought to estimate diabetes progression rates in a large cohort of subjects who newly developed “pre-diabetes” under both the older and newer criteria for IFG. In addition, we sought to identify predictors of diabetes progression among subjects who met each criterion for IFG.

RESERCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Subjects and Setting

Subjects were members of Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), a not-for-profit, group-model HMO serving approximately 475,000 members centered in the Portland, Oregon metropolitan area. KPNW maintains electronic databases containing information on all inpatient admissions, pharmacy dispenses, outpatient visits, and laboratory tests. The medical group recommends lipid screening for men age 35 and older and women age 45 and older. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) tests are routinely ordered with lipid panels. Between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2003, a single regional laboratory analyzed 603,486 FPG tests for 231,093 unique individuals. Of the 113,687 patients who had at least two tests, we identified 28,335 with two or more results of at least 100mg/dl and no evidence of diabetes (chart diagnosis of ICD-9-CM codes of 250.xx, FPG > 125mg/dl, or use of an anti-hyperglycemic drug) prior to the first elevated FPG test. From these, we identified 5,452 who also had an FPG test < 100mg/dl prior to their IFG-positive tests to ensure that the first elevated glucose test represented an “incident” value.

Stages of Impaired Fasting Glucose

For this study, we divided IFG into two “stages” that correspond to the old and new ADA criteria, 100–109 mg/dl (Added IFG) and 110–125 mg/dl (Original IFG). In both stages, patients were followed from the date of their first abnormal glucose until they progressed to diabetes (n=614, 11.3%), died (n=349, 6.4%), left the health plan (n=1,044, 19.1%), or until 31 December 2005 (n=3,445, n=63.2%). Added IFG subjects who later progressed to Original IFG were included in analyses of both stages. The mean number of follow-up fasting glucose tests was 5.2 ± 3.8 after entering the Added IFG stage, and 5.7 ± 4.3 after entering the Original IFG stage.

Analytic Variables

All analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We calculated incidence of diabetes per 100 person-years. For ease of interpretability, we report the incidence rates in terms of percent per year. To identify predictors of progression to diabetes, we constructed three generalized linear regression models using person-years of follow-up as an adjustment for unequal follow-up,12 one for all 5,452 subjects, a second for all 4,526 Added IFG subjects, and the third for all 1,699 Original IFG subjects. We also estimated a fourth model to identify predictors of progression to Original IFG among the 4,526 Added IFG subjects.

KPNW uses an electronic medical record (EMR) that contains up to 20 physician-recorded ICD-9-CM diagnoses at each contact. From these diagnoses, we identified comorbidities present at the time of the first fasting glucose test. The specific comorbidities (ICD-9-CM codes) used were: myocardial infarction [MI] (410.xx); stroke (430.xx-432.xx, 434.xx-436.xx, 437.1); other atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [ASCVD] (411.1, 411.8, 413.xx, 414.0, 414.8, 414.9, 429.2); congestive heart failure [CHF] (428.xx); and depression (296.2–296.35, 298.0, 300.4, 309.1, 311). In constructing the multivariate models, we combined the MI, stroke, ASCVD and CHF variables into a single marker for cardiovascular disease. Depression was not significant in any model, and was therefore dropped. Age was calculated as of the date of the first elevated glucose test. Smoking history, height, weight and blood pressure were also obtained from the EMR. Lipid values were extracted from the laboratory database. For this study, we used as predictors the mean of all lipid, blood pressure and BMI values recorded during a stage of IFG. Prior to modeling, we tested the correlation of all variables to rule out multicollinearity. With the exception of age/CVD (0.31) and female sex/HDL (0.37), all correlation coefficients were below 0.30, so any variable that was significant in any model was retained.

RESULTS

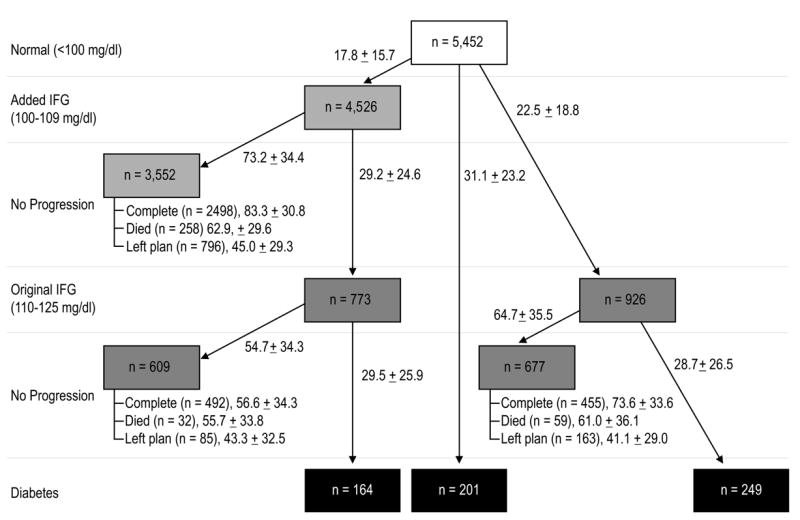

Of the 5,452 subjects, 4,526 (83.0%) had their first abnormal FPG within the Added IFG range in an average of 17.8 months after their last normal test (Figure 1). The remaining 926 (17.0%) subjects’ first abnormal fasting glucose result fell between 110–125 mg/dl (Original IFG) after an average of 22.5 months. Most Added IFG subjects (n=3,552, 78.5%) did not progress to either Original IFG or diabetes over a mean follow-up of 73.2 months. However, 201 Added IFG subjects (4.4%) progressed straight to diabetes in an average of 31.1 months. The remaining 17.1% progressed to Original IFG in a mean of 29.2 months. Of these, 164 (21.2%) developed diabetes in a mean of 29.5 months. Although nearly 30% of those who did not progress to either diabetes or Original IFG either died or left the health plan, mean follow-up time (62.9 months for those who died and 45.0 months for those who left the plan) was substantially longer than progression times. Similarly, 249 (26.9%) of initially Original IFG subjects developed diabetes in a mean of 28.7 months. Again, mean follow-up time among those who died or left the plan prior to progressing was much greater than progression time (61.0 and 41.1 months, respectively).

Figure 1.

Progression from normal fasting plasma glucose to stages of Impaired Fasting Glucose to Type 2 Diabetes. Mean months (± standard deviation) from stage to stage for progressers are displayed along each arrow. For those who do not progress, mean months (sd) of follow-up are displayed along the arrows.

Characteristics of Subjects by Initial Impaired Fasting Glucose Stage

The 83% of subjects whose initial abnormal FPG ranged from 100–109 mg/dl (Added IFG) were about two years older (59.7 vs. 57.9, p<.0001) and less likely to be women (48.1% vs. 53.9%, p<.001) than initially Original IFG subjects (Table 1). The mean value of the FPG test prior to the initial abnormal FPG did not significantly differ between Added and Original IFG subjects (93.8 vs. 93.5 mg/dl, p=0.119).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects by initial stage of Impaired Fasting Glucose.

| Added IFG

(100–109 mg/dl) |

Original IFG

(110–125 mg/dl) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of Subjects | 4,526 (83.0%) | 926 (17.0%) | -- |

| Months of Follow-up* | 75.6 (34.1) | 68.2 (35.2) | <0.0001 |

| Age at IFG Incidence | 59.7 (11.1) | 57.9 (11.6) | <0.0001 |

| Percent Female | 48.1% | 53.9% | 0.001 |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose: | |||

| Prior to IFG Incidence | 93.8 (4.8) | 93.5 (5.4) | 0.119 |

| Incident Measure | 103.5 (2.8) | 115.4 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| Months Between Pre and Incident FPG | 17.8 (15.7) | 22.5 (18.8) | <0.0001 |

| Current Smoker | 22.1% | 24.0% | 0.206 |

| Comorbidities: | |||

| History of MI | 9.1% | 8.4% | 0.524 |

| History of Stroke | 9.2% | 8.6% | 0.595 |

| Other ASCVD | 21.5% | 18.6% | 0.045 |

| CHF | 7.5% | 10.6% | 0.002 |

| History of Depression | 24.0% | 30.6% | <0.0001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 134 (13) | 136 (13) | 0.017 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 79 (7) | 80 (7) | 0.033 |

| Body Mass Index | 31.0 (6.3) | 33.2 (7.2) | <0.0001 |

| HDL Cholesterol | 51 (15) | 48 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides | 190 (215) | 212 (138) | 0.004 |

| LDL Cholesterol | 126 (30) | 121 (31) | <0.0001 |

Follow-up was terminated at the earlier of progressing to diabetes (11.3%), health plan termination (19.1%), death (6.4%), or 12/31/2005 (63.2%).

Progression to Diabetes

Overall, 8.1% of Added IFG subjects and 24.3% of Original IFG subjects ultimately developed diabetes (p<.0001, Table 2). Added IFG subjects who progressed to diabetes did so within a mean of 41.4 months, a rate of 1.34% per year. Of the 17.1% who progressed to Original IFG, 21.2% developed diabetes (3.24% per year). Among Added IFG subjects who were not known to progress to Original IFG, 5.4% developed diabetes (0.91% per year).

Table 2.

Proportion of Subjects Progressing to Diabetes, Months Until Progression, and Rate of Progression, by IFG Stage.

| Added IFG (100–109 mg/dl)

|

Original IFG (110–125 mg/dl)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did Not Progress to Original IFG | Progressed to Original IFG | Total, Added IFG | Initial IFG Stage was Added IFG | Initial IFG Stage was Original IFG | Total, Original IFG | Total, All Subjects | |

| Number (%) of Subjects | 3,753 (82.9%) | 773 (17.1%) | 4,526 | 773 (45.5%) | 926 (54.5%) | 1,699 | 5,452 |

| Number (%) Progressing to Diabetes1,2,3 | 201 (5.4%) | 164 (21.2%) | 365 (8.1%) | 164 (21.2%) | 249 (26.8%) | 413 (24.3%) | 614 (11.3%) |

| If Progressed to Diabetes, Mean (SD) Months from 1st FPG measure in stage to progression to diabetes1,3 | 31.1 (23.2) | 54.1 (27.6) | 41.4 (25.8) | 29.5 (25.9) | 28.7 (26.5) | 29.0 (26.2) | 36.3 (27.9) |

| Diabetes Incidence per Year1,3 | 0.91% | 3.24% | 1.34% | 5.16% | 5.87% | 5.56% | 1.95% |

Among Added IFG subjects, those who did and did progress to Original IFG differ significantly, p<0.0001

Among Original IFG subjects, those whose initial IFG stage was Added vs. Original IFG differ significantly, p=0.007

Total Added and Original IFG subjects differ significantly, p<0.0001

Subjects whose first elevated fasting glucose result was 110–125 mg/dl (Original IFG) converted to diabetes at a rate of 5.56% per year after an average of 29.0 months. Once subjects reached Original IFG, diabetes arose at approximately the same rate among subjects who did and did not pass through the Added IFG stage (5.16% vs. 5.87%, ns), but a significantly greater proportion of those who had not had a previous Added IFG measurement progressed to diabetes (26.8% vs. 21.2%, p=0.007). Among all subjects (n=5,452), 11.3% developed diabetes in an average of 36.3 months, an incidence rate of 1.95% per year. This represents the rate at which subjects under the new ADA definition of IFG (100–125 mg/dl) progressed to diabetes. By comparison, the total Original IFG incidence rate (5.56% per year) represents the old IFG definition.

Predictors of Hyperglycemic Progression

As shown in Table 4, each additional mg/dl of initial fasting glucose increased risk of progression to from Added to Original IFG (Model A) by 8% (Odds ratio [OR] 1.08, 95% CI 1.05–1.12), and from Added IFG to diabetes (Model B) by an identical 8% (1.08, 1.04–1.13). From Original IFG (Model C), each additional mg/dl of baseline fasting glucose increased risk of progression to diabetes by 7% (1.07, 1.04–1.10). In Model B, progression from Added to Original IFG tripled the risk of ultimately progressing to diabetes (3.11, 2.43–3.98). Younger age and female sex predicted progression to diabetes from both stages. In all models, each kg/m2 of BMI increased risk of progression by 3–4%, and HDL cholesterol was also a strong predictor. Higher systolic blood pressure and higher triglycerides were significant predictors of hyperglycemic progression in all models.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study of real-world patients with incident IFG, we found that 8.1% who met the added portion of the ADA’s 2003 criterion for IFG (100–109 mg/dl) progressed to diabetes over a mean follow-up of 6.3 years, an annual rate of 1.34%. Among subjects with incident IFG under the old ADA definition, 110–125 mg/dl, we observed an annual rate of progression to diabetes of 5.56%. This rate of progression is lower than rates reported by all but one previous study of subjects enrolled at unknown times after IFG had already begun.3,5–8 The progression rate from the old IFG cut-point that we observed is very similar to the rate reported by Meigs et al. in the only previous study that estimated progression from the time IFG first appeared.9 This confirms the importance of accounting for time since IFG onset when predicting the risk of diabetes, and likely explains much of the wide variation among earlier studies.

Three times the proportion of subjects with Original IFG progressed to diabetes than Added IFG subjects, and they did so more rapidly, at over four times the rate. Among Added IFG subjects, progression to Original IFG increased the risk of ultimately developing diabetes three-fold. Once Original IFG was reached, initially Added IFG subjects developed diabetes at approximately the same rate as patients who started from Original IFG. Only about one-third of subjects who developed diabetes did so without first passing through Original IFG. Moreover, the rate of diabetes incidence among all subjects (i.e., the rate for the ADA’s new IFG definition) was 1.95% per year, less than half the 5.56% rate observed for the old IFG definition. All these finding suggest that Original IFG (the old ADA definition) is much more predictive of future diabetes.

How quickly fasting glucose rises from normal to impaired may also predict type 2 diabetes. Although diabetes developed approximately equally among Original IFG subjects once that level was reached, subjects who first passed through Added IFG spent an average of 29.2 months in that stage. Thus, a steeper trajectory of rising fasting glucose may be an important risk factor for diabetes development. If so, whether a patient exceeds any given cut-point for defining IFG may be less important than the rate at which glucose is increasing. This is a new finding—it could not have been observed in previous studies of progression to diabetes with unknown dates of IFG onset, but it is consistent with the Mexico City Diabetes Study, which concluded that conversion to diabetes is marked by a step increase rather than gradual progressive rise in glycemia.13

In our data, higher BMI and lower HDL cholesterol were the most highly significant non-glucose predictors of hyperglycemic progression. Higher triglycerides and systolic blood pressure were also consistently significant risks. Previous studies have shown that this constellation of risk factors plus hyperglycemia—known as the metabolic syndrome—is predictive of diabetes, probably because of the glucose component.14–17 In the context of elevated glucose, components of the metabolic syndrome appear to independently predict further hyperglycemia, but whether the syndrome predicts diabetes over and above its individual components is beyond the scope of this study.

The prevalence of diabetes increases markedly with age.1 In our population of patients with newly acquired IFG, we found that younger, not older age predicted diabetes development. It may be that hyperglycemia developed at a younger age reflects a greater degree of insulin resistance, in which relatively small declines in beta cell function lead to a rapid rise in glucose levels.13 However, it is also possible that presence of other risk factors caused clinicians to test glucose more frequently among younger members, increasing the chance to identify diabetes.

Our study has several noteworthy limitations. As an observational study conducted in a clinical care setting, subjects received their fasting glucose tests at irregular intervals, which likely affected the precision of our incidence estimates. Although all subjects had previously normal fasting glucose measures, we could not determine the precise date on which they crossed an IFG threshold. In addition, by requiring our subjects to have at least two elevated glucose values, our study may have been subject to ascertainment bias—some of our subjects were likely being followed because of glucose-related risk factors. Furthermore, those at greatest diabetes risk may have been tested more frequently, thereby increasing the likelihood of detection. Therefore, our incidence estimates may be higher than would be observed in a randomly selected population, but are likely representative of real-world clinical practice. An additional limitation is that 19% of our initial population disenrolled from the health plan. Over an average of six years of follow-up, this computes to a relatively low drop out rate of less than four percent. Whether these subjects would experience diabetes incidence at similar rates to those for whom complete follow-up was available cannot be determined. Had we excluded these subjects from analysis, our progression rates would have been considerably higher, because the denominator would have been reduced while the number of subjects progressing remained the same. It is also important to note that at all stages of progression, subjects who died or left the health plan prior to progression were, on average, observed for substantially longer periods than the mean progression times for those who did progress. Moreover, other than being younger, disenrollees were not statistically significantly different from those with complete follow-up on any of the predictor variables, including fasting glucose levels. We were also unable to assess several known predictors of diabetes—family history, previous gestational diabetes, race/ethnicity, and waist circumference, for example. Exclusion of these predictors from multivariate models may have affected the performance of included variables in ways we could not observe. Finally, our study was conducted in an insured primarily Caucasian (~92%) population. Whether our results generalize to other populations is an important area for future research.

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study concluded that two-thirds of those classified at the lower (100–109mg/dl) IFG cut-point had either diabetes or IGT.18 Thus, because many IFG patients also have IGT, interventions proven effective in IGT populations19–22 would likely also apply to the majority of IFG patients. However, the implementation of lifestyle interventions takes time, and the beneficial effects are not immediate. In our data, newly identified Added IFG subjects who progressed to diabetes took, on average, over three years to do so. Even among those with newly acquired Original IFG, diabetes progression time averaged over two years. However, those at greatest risk of diabetes had steeper trajectories of glucose increase, allowing less time for time-intensive interventions. Current ADA recommendations suggest screening to detect pre-diabetes and diabetes in high risk individuals, particularly those with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, at 3-year intervals.1 Overall, those who developed diabetes in our study did so in an average of 36.3 months, and Original IFG subjects who developed diabetes did so in a mean of approximately 29 months. Thus, a three-year screening interval could miss individuals who progress rapidly from normal to impaired glycemia to diabetes. Shortening the screening interval, especially among the obese and those with steeper glucose trajectories, would allow more time for at-risk individuals to attempt lifestyle interventions.

Table 3.

Multivariate Models of Hyperglycemic Progression

| Model A: Progression from Added to Original IFG | Model B: Progression from Added IFG to Diabetes

|

Model C: Progression from Original IFG to Diabetes

|

Model D: Progression from Either Stage to Diabetes

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

| Progressed to Original IFG | -- | -- | -- | 3.11 | 2.43 – 3.98 | <0.0001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Initially Added IFG | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.12 | 0.88 - 1.42 | 0.352 | -- | -- | -- |

| Initially Original IFG | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.61 | 1.12 – 2.32 | 0.010 |

| Initial FPG in stage (per mg/dl) | 1.08 | 1.05 – 1.12 | <0.0001 | 1.08 | 1.04 – 1.13 | 0.0003 | 1.07 | 1.04 – 1.10 | <0.0001 | 1.07 | 1.04 – 1.10 | <0.0001 |

| Age (per 10 Years) | 0.98 | 0.93 – 1.02 | 0.311 | 0.92 | 0.86 – 0.99 | 0.020 | 0.92 | 0.87 – 0.98 | 0.015 | 0.92 | 0.88 – 0.97 | 0.002 |

| Female Sex | 1.05 | 0.87 – 1.28 | 0.611 | 1.47 | 1.11 – 1.93 | 0.007 | 1.33 | 1.02 – 1.72 | 0.032 | 1.44 | 1.17 – 1.77 | 0.781 |

| History of CVD | 1.28 | 1.05 – 1.55 | 0.013 | 0.90 | 0.68 – 1.19 | 0.455 | 0.99 | 0.76 – 1.30 | 0.959 | 1.03 | 0.83 – 1.28 | 0.781 |

| Current Smoker | 0.99 | 0.80 – 1.23 | 0.944 | 1.51 | 1.15 – 1.99 | 0.003 | 1.17 | 0.89 – 1.53 | 0.255 | 1.24 | 1.00 – 1.54 | 0.047 |

| BMI (per kg/m2) | 1.03 | 1.02 – 1.05 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.02 – 1.06 | <0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.02 – 1.05 | <0.0001 | 1.04 | 1.03 – 1.06 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP (per 5mmHg) | 1.04 | 1.00 – 1.08 | 0.066 | 1.10 | 1.04 – 1.16 | <0.0001 | 1.08 | 1.03 – 1.14 | 0.001 | 1.09 | 1.05 – 1.14 | <0.0001 |

| HDL-C (per 5mg/dl) | 0.93 | 0.89 – 0.96 | 0.0001 | 0.88 | 0.83 – 0.93 | <0.0001 | 0.88 | 0.84 – 0.93 | <0.0001 | 0.87 | 0.84 – 0.91 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-C (per 5mg/dl) | 1.01 | 0.99 – 1.02 | 0.340 | 0.97 | 0.95 – 0.99 | 0.003 | 0.99 | 0.97 – 1.01 | 0.411 | 1.02 | 0.97 – 1.00 | 0.030 |

| Triglycerides (per 50mg/dl) | 1.01 | 1.00 – 1.02 | 0.002 | 1.01 | 1.00 – 1.02 | 0.026 | 1.03 | 1.01 – 1.04 | 0.0003 | 1.01 | 1.01 – 1.02 | 0.001 |

Footnotes

Funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant No. 1 R21 DK063961

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus; Clinical practice recommendations 2006. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(Supplement 1):S1–S85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabet Med. 2002;19:708–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vegt F, Dekker JM, Jager A, Hienkens E, Kostense PJ, Stehouwer CDA, et al. Relation of impaired fasting and postload glucose with incident type 2 diabetes in a Dutch population. JAMA. 2001;285 (16):2109–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eschwege E, Charles MA, Simon D, Thibult N, Balkau B. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of diabetes over a 30-month follow-up: The Paris Prospective Study. Diabetes Care. 2001;24 (11):1941–1944. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.11.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaccaro O, Ruffa G, Imperatore G, Iovino V, Rivellese AA, Riccardi G. Risk of diabetes in the new diagnostic category of impaired fasting glucose: a prospective analysis. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1490–1493. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, de Courten M, Dowse GK, Chitson P, Gareeboo H, et al. Impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance. What best predicts future diabetes in Mauritius. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):399–402. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabir MM, Hanson RL, Dabelea D, Imperatore G, Roumain J, Bennett PH, et al. The 1997 American Diabetes Association and 1999 World Health Organization criteria for hyperglycemia in the diagnosis and prediction of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(8):1108–1112. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimeno SG, Ferreira SR, Franco LJ, Iunes M. Comparison of glucose tolerance categories according to World Health Organization and American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria in a population-based study in Brazil. The Japanese-Brazilian Diabetes Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1889–1892. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.11.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meigs JB, Muller DC, Nathan DM, Blake DR, Andres R. The natural history of progression from normal glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Diabetes. 2003;52:1475–1484. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.6.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Follow-up Report on the Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3160–3167. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borch-Johnsen, Colagiuri S, Balkan B, Glumer C, Carstensen B, Ramachandran R, et al. Creating a pandemic of prediabetes: the proposed new diagnostic criteria for impaired fasting glucose. Diabetologia. 2004;47(8):1396–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1468-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stokes ME, Davis CS, Koch GG. Categorical data analysis using the SAS system. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrannini E, Nannipieri M, William K, Gonzales C, Haffner SM, Stern MP. Mode of onset of type 2 diabetes from normal or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 2004;53(1):160–165. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenzo C, Okoloise M, Williams K, Stern MP, Haffner SM San Antonio Heart Study. The metabolic syndrome as predictor of type 2 diabetes: the San Antonio Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3153–3159. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laaksonen DE, Lakka HM, Niskanen LK, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Lakka TA. Metabolic syndrome and development of diabetes mellitus: application and development of recently suggested definitions of the metabolic syndrome in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:1070–1077. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson RL, Imperatore G, Bennett PH, Knowler WC. Components of the "metabolic syndrome" and incidence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:3120–3127. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley AJG, Karter AJ, Williams K, Festa A, D'Agostino RB, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Prediction of type 2 diabetes mellitus with alternative definitions of the metabolic syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Circulation. 2005;112:3713–3721. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.559633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Vigo A, Pankow J, Ballantyne CM, Couper D, et al. Detection of undiagnosed diabetes and other hyperglycemic states: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1338–1343. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with life-style intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuomilehto J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M, et al. Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes: the STOP-NIDDM randomized trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2072–2077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(4):537–544. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]