Abstract

Blood coagulation is strongly dependent on the binding of vitamin K-dependent proteins to cell membranes containing phosphatidylserine (PS) via γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) domains. The process depends on calcium, which can induce nonideal behavior in membranes through domain formation. Such domain separation mediated by Ca2+ ions or proteins can have an important contribution to the thermodynamics of the interaction between charged peripheral proteins and oppositely charged membranes. To characterize the properties of lipid-lipid interactions, molecular dynamics, and free energy simulations in a mixed bilayer membrane containing dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine and dipalmitoylphosphatidylserine were carried out. The free energy of association between dipalmitoylphosphatidylserines in the environment of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholines has been calculated by using a novel approach to the dual topology technique of the PS-PC hybrid. Two different methods, free energy perturbation and thermodynamic integration, were used to calculate the free energy difference. In thermodynamic integration runs three schemes were applied to evaluate the integral at the limits of λ → 0 or λ → 1. Our studies show that the association of two PSs in the environment of PCs is repulsive in the absence of Ca2+ and becomes favorable in their presence. We also show that the mixed component membrane should exhibit nonideal behavior that will lead to PS clustering.

INTRODUCTION

Negatively charged phospholipids such as phosphatidylserines (PS) in a lipid membrane composed of neutral phosphatidylcholines (PC) provide an anchor for vitamin K-dependent zymogens and thus play an essential role in activating of the blood coagulation cascade (1–4). Upon vascular tissue damage, PSs are exposed on the surface of the epithelial cells, and in a Ca2+-dependent process blood-borne proteases—factors VII, IX, X, and prothrombin—are anchored to the negatively charged phospholipids through the N-terminal γ-carboxyglutamic acid containing domains (Gla domains). The importance of such an event has been amply demonstrated (e.g., (5)) and it serves as a basis for anticoagulant therapy through the use of inhibitors that prevent the vitamin K-dependent posttranslational modification of glutamates to Gla (6).

The molecular details of the interaction between PS and Gla domains have been recently illustrated in the crystal structure of the Gla domain of prothrombin fragment 1 (PT1) in complex with a lysoPS (7). The structure shows that the anchoring of the negatively charged Gla domain to a negatively charged PS is mediated via Ca2+ ions. The high conservation of the Gla domains in other proteins suggests a similar mechanism of anchoring of proteins such as zymogene II, factor Xa, and cofactor Va (8,9). In addition to anchoring proteins via their Gla domains, PSs also regulate allosterically both factors Xa and Va (9–11), and have been proposed to act as a second messenger because they link platelet activation (IIa, collagen) to thrombin generation (5).

Electrostatic interactions are the driving force for binding peripheral proteins to negatively charged membranes (12). The thermodynamics of this process has been studied both experimentally and theoretically (13–16). The distribution of the negatively charged lipids in the membrane before protein association has to be taken into consideration to properly account for the entropic contribution of demixing to the binding free energy and absorption isotherms (17–20). The model of Denisov et al. (17) postulates that electrostatic interactions with small basic peptides produce lateral membrane domains enriched in acidic lipids. The model by Heimburg et al. (18), describes the influence of lipid redistribution upon protein adsorption on mixed lipid membranes. This model, with appropriate interaction parameters, predicts the experimental adsorption isotherm of cytochrome c on mixed dioleoyl phosphatidylglycerol/dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayer membrane. The model of May et al. (19) starts with a mixture of negatively charged (e.g., PS) and zwitterionic (e.g., PC) lipids distributed homogenously, and introduces the contribution of lipid demixing to the free energy of protein-membrane association through an entropic term. The minimization of the free energy functional establishes the relationship between electrostatic and entropic contributions in the binding process between charged proteins and lipids. The critical assumption of the model is the homogenous distribution of the lipids at initial conditions, despite the fact that the PS/PC mixtures are nonideal (21). Therefore, a better estimation of the initial conditions would be required to properly estimate the binding free energy of proteins to charged lipids.

In mixed bilayers, such as those formed by PC and PS molecules, lateral phase separation occurs in the presence of Ca2+ and Mg2+ due to lipid-ion interactions as well as due to lipid-lipid interactions (22–25). Previous works have dealt with the problem of the effect of Ca2+ ions in leading to aggregation in membranes containing negatively charged lipids (26,27) demonstrating that in liposomes made from PS, addition of Ca2+ leads to aggregation, followed by vesicle fusion and leakage. It has been recently shown that the effectiveness of cations in inducing aggregation and fusion in N-palmitoylphosphatidylethanol-amine and N-palmitoylphosphatidylserine liposomes is Ca2+ > Mg2+ ≈ Na+ (28). Likewise, a calcium-mediated association between the carbohydrate headgroups of the galactosylceramide-I3-sulfate and galactosylceramide has been demonstrated by vesicle aggregation and electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (29–31). Thus, the involvement of Ca2+ in lipid aggregation plays an important and as yet not fully understood role.

We have designed a lipid membrane system to study the energetics of lipid-lipid association by using molecular dynamics simulation, free energy perturbation (FEP), and thermodynamic integration (TI) (32,33). The aim of this work is to elucidate the association of two dipalmitoylphosphatidylserines (DPPS) in the environment of a dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) membrane and estimate the role of Ca2+ in this process. The first part of the article describes the methods and the models used in our studies. The free energy thermodynamic integration formalism and the free energy perturbation method are briefly reviewed. We then present the results of simulations of the lipid membrane with and without Ca2+ ions. We present and discuss the free energy calculations of the association between two DPPSs in the environment of DPPCs and use the results to estimate the effect of lipid-lipid interaction on the nonideality of the mixed membrane. We find that the association between DPPSs in the environment of DPPCs is favorable only in the presence of Ca2+ ions.

METHODS AND MODELS

The membrane model

The construction of the lipid membrane followed a standard protocol (34). The general strategy is to randomly select phospholipids from a preequilibrated and prehydrated library of DPPC generated by Monte Carlo simulations in the presence of a mean field (35–37). The lipids are placed in a periodic system and the number of core-core overlaps between heavy atoms is reduced through systematic rotations around the z axis and translations in the xy-plane. All waters that overlap with the hydrocarbon interior of the bilayer, between ±12 Å in the z-direction, were deleted. The initial configuration of the model comprised 48 DPPCs and 2009 water molecules, which represent a hydration level of 52%. Two DPPCs in each layer were replaced by two DPPSs in such a way as to generate in both layers of the membrane two PSs separated by one PC in the middle (Scheme I). The radial distribution function of the phosphorous atoms of DPPC yields a distance of ∼6 Å between the P atoms, which was used to set up the initial configuration. To prepare the solvated DPPS in the DPPC environment, we removed all the water and performed grand canonical ensemble Monte Carlo simulations (GCMC) to solvate the system again. At the end, the system consisted of 44 DPPC, four DPPS, and 1960 water molecules, which amounts to a total of 12,092 atoms. To neutralize the system, we substituted two water molecules by two calcium ions (Ca2+). In the new initial configuration the calcium ions were placed approximately in the middle between two DPPS. The initial distances between the phosphorus atoms of each DPPS and the Ca2+ in the upper layer (lower layer) was 12.54 Å (9.76 Å) and 11.06 Å (10.30 Å) and between the DPPS was 11.63 Å (11.62 Å). We decided on this initial placement of the Ca2+ ions after having seen in preliminary simulations that Ca2+ ions placed far from the DPPSs invariably moved into their vicinity. At this level of treatment we also decided against using added salt to represent physiological ionic strength since at this system size it would only add 5–10 ion pairs, resulting in increased fluctuations and thus the need for excessively long runs.

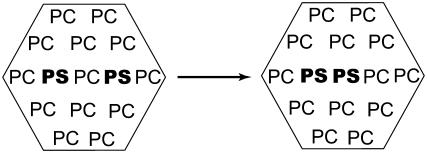

SCHEME I.

Interconversion between DPPS and DPPC form the PS/PC/PS to a PS/PS/PC configuration in the environment of PC. The most probable distance, obtained from the radial distribution function of the phosphorous atoms of DPPC, is ∼6 Å.

Setup of the simulation

Hexagonal periodic boundary conditions were applied in the xy-plane to maximize the distance between two periodic images (38). The edge of the hexagon and the length of the prism were 24.3 Å and 75.0 Å, respectively, with a center-to-center distance between neighboring cells of 42.1 Å and the center of the bilayer membrane located at Z = 0. The all-atom CHARMM27 force field for phospholipids (39) and the TIP3P water model (40) was used in all calculations. Long-range interactions were treated by a group-based spherical cutoff at 12 Å. The van der Waals and electrostatic interactions were smoothly switched over a distance of 8.0 Å. The equilibration was carried out using Langevin dynamics with decreasing planar harmonic constraints of 10, 5, 1, 0.5, 0 kcal/mol/Å2 on water and lipids for 25 ps in each stage, so that by the end of 125 ps, the full system was completely unrestrained. The GCMC simulation to obtain the solvation of the mixed system was then performed for 9.5 million MC steps. The chemical potential value used in the (μ, V, T) ensemble was obtained from a set of preliminary test runs, in which the water density in a 10-Å layer farthest from the lipids was monitored while the excess chemical potential was varied through the choice or the parameter B as expressed in the equation  where

where  is the Boltzmann constant, T the absolute temperature of the system, and

is the Boltzmann constant, T the absolute temperature of the system, and  is the average number of waters. The final value of

is the average number of waters. The final value of  produced an average density of 0.99719 g/ml. This was followed with a constant pressure, temperature, and area protocol (CPTA) production molecular dynamics for 5 ns. The temperature of the system was maintained at 330 K, which is above the gel-liquid crystal phase transition of DPPC. In the production stage the temperature was maintained using the Nose-Hoover scheme. The length of all bonds involving hydrogen atoms was kept fixed with the SHAKE algorithm (41). The equations of motion were integrated with a time step of 2 fs. All simulations were performed using the CHARMM program (42) and the Metropolis Monte Carlo program (MMC) (43).

produced an average density of 0.99719 g/ml. This was followed with a constant pressure, temperature, and area protocol (CPTA) production molecular dynamics for 5 ns. The temperature of the system was maintained at 330 K, which is above the gel-liquid crystal phase transition of DPPC. In the production stage the temperature was maintained using the Nose-Hoover scheme. The length of all bonds involving hydrogen atoms was kept fixed with the SHAKE algorithm (41). The equations of motion were integrated with a time step of 2 fs. All simulations were performed using the CHARMM program (42) and the Metropolis Monte Carlo program (MMC) (43).

Free energy simulation methods

A conventional approach to the evaluation of free energy of association in fluid mixtures relies on the calculation of the free energy profile of the selected species as a function of the distance that separates them. For lipid bilayers such a calculation presents formidable difficulties due to the extremely slow lateral diffusion of lipid molecules. We therefore decided to perform simultaneous exchanges of lipid headgroups from a (PS/PC/PS)PC configuration into a (PS/PS/PC)PC configuration, as shown in Scheme I. This results in the conversion of a PC-separated pair of PSs into a near-neighbor adjacent pair. In addition to eliminating the calculation of a distance-dependent free energy profile, this approach has the additional advantage that the mutations involve only the headgroups since the hydrocarbon chains of DPPC and DPPS are identical. Because the lipid portions of PC and PS are the same we used a dual topology of the PS-PC hybrid that involves only the headgroups (see Fig. 1). In this approach, the parts of the system, which are not the same in the initial and the final states, coexist at all times as the free energy simulation is carried out. They interact with the environment but not with each other (44). Thus, in the potential energy of this system, expressed as a function of a parameter λ that describes such a transformation, only the phosphocholine of the PC and phosphoserine of the PS are weighted by λ:

|

(1) |

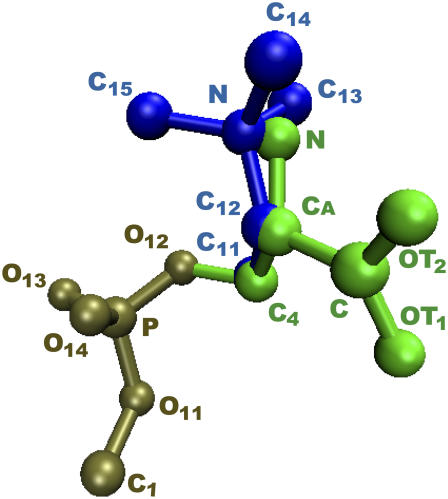

FIGURE 1.

Local dual topology of the PS-PC hybrid residue. The conformation shown is the starting geometry used in the dynamics. The atoms of the choline headgroup (N, C12, C11, blue) are superimposed on the corresponding atoms in the serine headgroup (N, CA, C4, green). The atoms were slightly shifted to make them visible.

The free energy calculations for two of the three runs were performed in two steps. When the calculation was performed in two steps, step 1 represented the interconversion of PS/PC/PS to PS/PS/PS and step 2 the interconversion of PS/PS/PS to PS/PS/PC. The potential energy of the systems is expressed in Eq. 1 with the steps represented by the superscripts. When the calculation is performed in one step, i.e., PS/PC/PS to PS/PS/PC, the subscripts a and b represent both residues; that is, a = PC/PS and b = PS/PC.

and

and  are the contributions of PS, PC, and the rest of the system, respectively (33,45). Phosphates of the two lipids as well as the first carbon of the glycerol with its hydrogens are included in the dual topology because they belong to the same group and have different partial charges in the CHARMM force field (39) (see Fig. 1).

are the contributions of PS, PC, and the rest of the system, respectively (33,45). Phosphates of the two lipids as well as the first carbon of the glycerol with its hydrogens are included in the dual topology because they belong to the same group and have different partial charges in the CHARMM force field (39) (see Fig. 1).

The free energy simulations at different λ-values were performed using the BLOCK module in the CHARMM program (46,47). Three blocks were defined: one for the reactant, one for the product, and another one for the rest of the system. Blocks 2 and 3 consisted of the choline and phosphate groups of PC and serine and phosphate groups of PS, respectively, as described in Fig. 1. The rest of the system forms block 1. The interaction energy between block 2 and block 3 was set to zero to eliminate unphysical interaction terms.

Both the free energy perturbation and the thermodynamic integration methods were used to compute the free energy for each λ-window on the same runs. The free energy difference for each step using FEP was computed with the following equation:

|

(2) |

where  indicates averaging at λi. In our calculations, double-wide sampling was used such that the perturbation was to the halfway point between the λ-values. The total free energy difference of the interconversion between PS/PC/PS and PS/PS/PC is given by the summation of

indicates averaging at λi. In our calculations, double-wide sampling was used such that the perturbation was to the halfway point between the λ-values. The total free energy difference of the interconversion between PS/PC/PS and PS/PS/PC is given by the summation of  and

and  The superscripts on the potential energy,

The superscripts on the potential energy,  and

and  refer to the step number. When such interconversion was performed in one step the two equations are merged into one,

refer to the step number. When such interconversion was performed in one step the two equations are merged into one,

When TI is used, the total free energy difference between λ = 0 and λ = 1 is:

|

(3) |

For linear λ-dependence, the derivative of the potential energy with respect to λ for each perturbation is:

|

(4) |

Thus, the change in the free energy is given by:

|

(5) |

Both methods have been shown to reproduce experimental values of the free energy differences in several systems (e.g., (48–50)).

Free energy simulations

Three different free energy simulation runs were performed. In the first two the change in one of the membrane layers was calculated: in run 1 the lower-layer system was used and in run 2 the perturbation was in the upper-layer system. The free energy calculations for both runs were carried out in two steps. Run 3 corresponds to the lower-layer system as well, but with different initial conditions and the calculations of the free energy were executed in only one step.

The value of λ was incremented from 0.1 to 0.9 in steps of 0.2 in FEP simulations. In TI, two sets of λ-values were used: the same values as in FEP for the system with calcium and those dictated by a five-point Gaussian quadrature for the system without calcium. The latter values were λ = 0.046910, 0.230765, 0.5, 0.769235, 0.953089 (51). Initially, the system was heated and equilibrated for 100 ps at λ = 0.1. At each λ-value, the system was reequilibrated for 50 ps and data were collected for another 100 ps, during which the trajectory was recorded every 50 fs, producing 2000 frames for each λ-value.

Evaluation of the integral in the TI

The trapezoidal rule was used to evaluate the integral from the discrete values of the free energy derivative between λ = 0.1 and λ = 0.9 and between λ = 0.046910 and λ = 0.953089. The values of the five-point quadrature coefficients, ci, were 0.118463, 0.239314, 0.284444, 0.239314, and 0.118463 (51). The coefficient for the first set of λ-values is constant and equals 0.2.

To improve the evaluation of the integral (Eq. 5), three different schemes to obtain the end-point contributions (regions near λ = 0 and λ = 1) were applied. Scheme 1 assumes that the free energy derivative  is constant and does not change in these intervals and the second derivative of the free energy is zero. Scheme 2 calculates the end-point contributions by extrapolation assuming that the third derivative of the free energy is constant. In this scheme it is assumed that the end-point values exist and are finite. Scheme 3 is based on the fact that when the Lennard-Jones interaction energy is scaled linearly, the free energy in three dimensions behaves like

is constant and does not change in these intervals and the second derivative of the free energy is zero. Scheme 2 calculates the end-point contributions by extrapolation assuming that the third derivative of the free energy is constant. In this scheme it is assumed that the end-point values exist and are finite. Scheme 3 is based on the fact that when the Lennard-Jones interaction energy is scaled linearly, the free energy in three dimensions behaves like  (33,52). Thus, the free energy derivative is proportional to

(33,52). Thus, the free energy derivative is proportional to  The end-point contributions

The end-point contributions  and

and  are calculated by:

are calculated by:

|

(6) |

where  and

and  are the closest values to the end points of the λ-simulations set and A is

are the closest values to the end points of the λ-simulations set and A is  for the

for the  limit and

limit and  for the

for the  limit; α and β are constants, which are determined by fitting the first and the second free energy derivatives evaluated at

limit; α and β are constants, which are determined by fitting the first and the second free energy derivatives evaluated at  and

and

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Simulations using a membrane without calcium ions

Average density profile

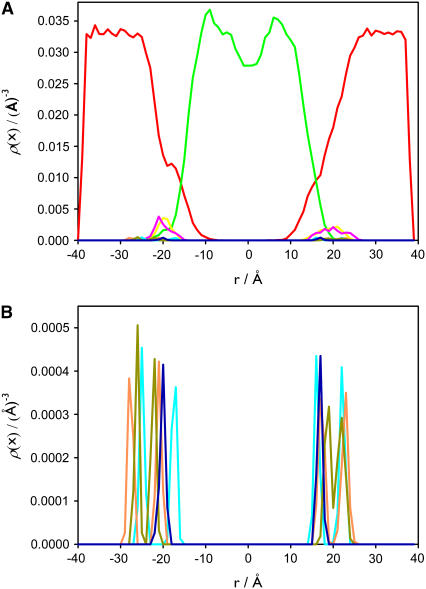

The density profile of the different components in both layers is nearly symmetrical (Fig. 2). The number density of water outside the lipid is ∼0.0334 Å−3, corresponding to a bulk solvent density, and it approaches zero in the hydrocarbon core region. The P and N atoms of the PC and PS headgroups are located approximately at the boundary between the lipid and the aqueous environment. The distribution of the angle between the phosphorous-nitrogen vector,  and the outwardly directed bilayer normal shows that the headgroups are approximately parallel to the membrane plane. The angle is 83° ± 23° for DPPC and 74° ± 10° for DPPS. The density of the hydrocarbon chain is reduced near the center of the membrane in agreement with other experiments and models of the bilayer system. The general features of the lipid density profile are similar to those observed for pure DPPC bilayers (53,54).

and the outwardly directed bilayer normal shows that the headgroups are approximately parallel to the membrane plane. The angle is 83° ± 23° for DPPC and 74° ± 10° for DPPS. The density of the hydrocarbon chain is reduced near the center of the membrane in agreement with other experiments and models of the bilayer system. The general features of the lipid density profile are similar to those observed for pure DPPC bilayers (53,54).

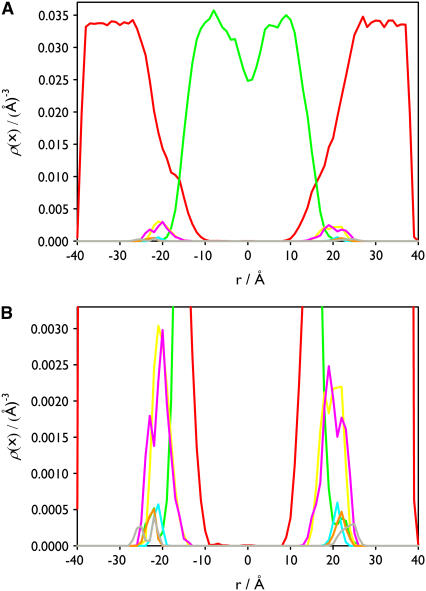

FIGURE 2.

Density profile of the main components for the lipid membrane without calcium ions along the z axis. The distribution of waters (red), hydrocarbon chains (green), P (yellow), N (pink) atoms of PC, and P (cyan), N (orange), and carboxyl group (gray) of PS are shown. In panel B the distribution of the components of the PC and PS headgroups represented in panel A are magnified.

Free energy of PS association in the absence of Ca2+

The values of the free energy difference ΔGPS/PC/PS→PS/PS/PC obtained with both methods FEP and TI are summarized in Table 1. Runs 1 and 2 represent independent free energy evaluations in the lower and upper layers, respectively. The different columns of the TI method summarize the results from the three schemes used to evaluate the integrand at the boundaries when λ → 0 or λ → 1 (see Methods and Models). All the results show that the free energy of PS association is positive indicating an unfavorable process. Further examination of the TI results shows that although the values are somewhat different from each other, the standard deviations make them statistically indistinguishable. The FEP yields the smallest free energy difference and the largest standard deviation mostly because of the large difference between the free energy values for the upper and lower layers. The presence of the exponential function in Eq. 2 results in a significant increase in the fluctuations of the calculated averages. This can lead to poorer convergence of the calculated free energy difference. Its mean value is also included in the energy interval obtained with TI. The contributions of the end points to the free energy difference are also listed in Table 1. The sum of both end-point contributions to the free energy is positive for all runs of both methods, FEP and TI.

TABLE 1.

Free energy differences for the exchange PS/PC/PS → PS/PS/PC in a DPPC membrane in the absence of calcium ions

| ΔG / (kcal/mol) [ΔGfirst end point-0.0 / ΔG1.0-second end point]

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI method

|

||||

| Run No.* | Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | Scheme 3 | FEP method |

| 1 | 19.34 [49.88 / −44.62]† | 19.94 [55.29 / −49.42]† | 23.94 [91.02 / −81.15]† | 9.52 [78.76 / −67.69]‡ |

| 2 | 25.21 [45.67 / −37.45]† | 26.04 [50.46 / −41.41]† | 31.66 [82.20 / −67.54]† | 24.80 [80.69 / −68.44]‡ |

| Mean ± SD§ | 22.28 (4.15) | 22.99 (4.31) | 27.80 (5.46) | 17.16 (10.80) |

Five-point Gaussian quadrature (λ = 0.04691, 0.230765, 0.5, 0.769235, 0.953089) was used to calculate the free energy differences using the linear TI method. In the FEP method five points (λ = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9) were used to calculate the free energy differences.

Runs 1 and 2 correspond to the calculation of the free energy in the lower-layer and the upper-layer systems, respectively. The lipid membrane is symmetric.

The values in square brackets are the  and

and  end-point contributions to the free energy differences, respectively.

end-point contributions to the free energy differences, respectively.

The values in square brackets are the  and

and  end-point contributions to the free energy differences, respectively.

end-point contributions to the free energy differences, respectively.

The standard deviation was computed as  and is given in parentheses; n is the number of runs.

and is given in parentheses; n is the number of runs.

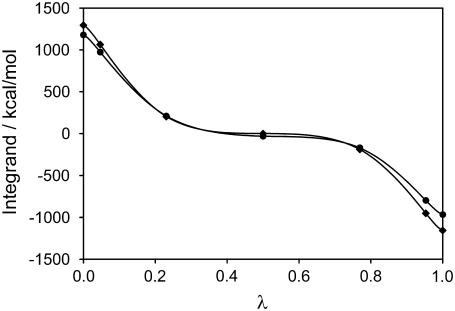

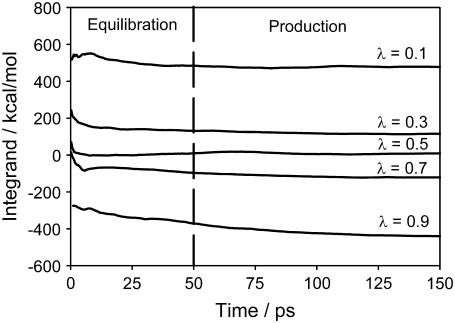

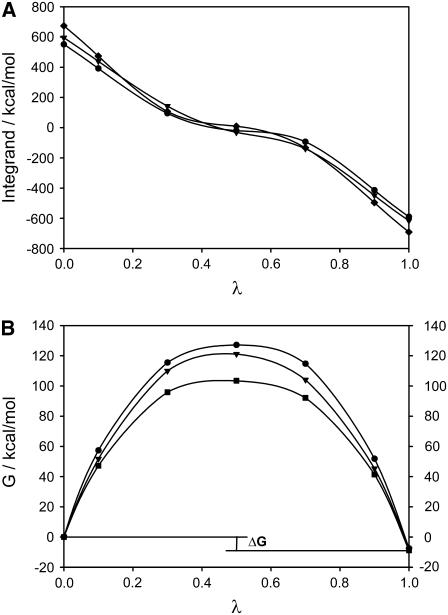

The total TI integrands (i.e., the contribution of the two steps, from PS/PC/PS to PS/PS/PC) of the TI method for both runs as function of λ are represented in Fig. 3. The values at the end points were obtained by extrapolation using Scheme 2 of integration (see Methods and Models). The dependence of the integrand on λ is very smooth, indicating that the TI method is a good choice for evaluating the free energy.

FIGURE 3.

TI integrand for the transition PS/PC/PS → PS/PS/PC. Five-point Gaussian quadrature fit polynomials were used to calculate the free energy differences in a lipid membrane without calcium ions. The values at the end points were obtained by extrapolation (see text). Run 1 (♦, lower layer) and run 2 (•, upper layer).

As expected, these results demonstrate that the association of two PS in the environment of PC without counterions is unfavorable. This binary unfavorable PS-PS association is clearly due to the electrostatic repulsion between the headgroups. However, it does not offer an opportunity to examine the forces that may lead to clustering in an ensemble of lipids.

Simulations using a membrane with calcium ions

Average density profile

The general density profiles of the water, the hydrocarbon chain, and the P and N atoms of the PC headgroup are similar to those in the lipid membrane without calcium ions. However, the distribution of the P and N atoms, and the carboxyl group of the PS headgroup in both layers is quite different. In both layers the distribution of the N atoms, the P atoms, and the carboxyl groups have two populations (Fig. 4). This is because the individual distributions represent different PSs, which are separated vertically. In both layers the distributions of calcium ions have only one peak, centered at 17.5 Å in the upper layer and at 20 Å in the lower layer. The distribution of calcium ion in the lower layer is located between the two peaks of the P atom distribution, whereas in the upper layer it coincides with one of the P atom distributions closer to the membrane. The distribution of the  of PC with respect to the bilayer normal has a value of 82° ± 23° (average over all PC). The PS headgroups of the lower layer prefer an orientation more outwardly directed (

of PC with respect to the bilayer normal has a value of 82° ± 23° (average over all PC). The PS headgroups of the lower layer prefer an orientation more outwardly directed ( vector

vector  ). DPPS most likely prefers this conformation due to the negative charge of the serine carboxyl group, which prefers to point out of the membrane. Nevertheless, the PS headgroups of the upper layer have the same orientation as the PC headgroups (

). DPPS most likely prefers this conformation due to the negative charge of the serine carboxyl group, which prefers to point out of the membrane. Nevertheless, the PS headgroups of the upper layer have the same orientation as the PC headgroups ( ). Further study of the orientation of the lipid headgroups may be required (54,55). Due to the structural differences observed in the two layers we calculated the free energy difference in both layers separately. The results are presented in the next section.

). Further study of the orientation of the lipid headgroups may be required (54,55). Due to the structural differences observed in the two layers we calculated the free energy difference in both layers separately. The results are presented in the next section.

FIGURE 4.

Density profile of the main components for the lipid membrane with calcium ions along the z axis. The distribution of the waters (red), hydrocarbon chains (green), P (yellow), N (pink) atoms of PC, and P (cyan), N (orange), and carboxyl group atoms of PS (gray), and Ca2+ (dark blue) are shown. In panel B the distribution of the components of the PC and PS headgroups represented in panel A are magnified.

Free energy of PS association in the presence of Ca2+

The potential energy derivative,  for each λ in run 1 (i.e., the upper layer) as a function of simulation time is shown in Fig. 5. These curves represent the cumulative average of

for each λ in run 1 (i.e., the upper layer) as a function of simulation time is shown in Fig. 5. These curves represent the cumulative average of  for all λ-values. The equilibration period during the initial 50 ps shows some fluctuations in the energy, which relax to the new λ-value and stabilize at the appropriate value of the integrand. This behavior is similar for other runs.

for all λ-values. The equilibration period during the initial 50 ps shows some fluctuations in the energy, which relax to the new λ-value and stabilize at the appropriate value of the integrand. This behavior is similar for other runs.

FIGURE 5.

TI integrand,  as a function of simulation time (ps) for all λ-values, run 1.

as a function of simulation time (ps) for all λ-values, run 1.

The presence of Ca2+ ions changes the free energy difference of the association between two PSs from a repulsive interaction to an attractive one (Table 2). Runs 1 and 2 represent independent free energy evaluations in the lower and upper layers carried out in two steps, respectively, and run 3 corresponds to the lower-layer system performed in only one step. The three schemes used to evaluate the integrand in the TI method show that the free energy of PS association in the presence of Ca2+ ions is negative, indicating a favorable process. The FEP method also yields negative values of free energy differences. Even though the mean values are not very different from each other for each method (TI and FEP), the standard deviations also make them statistically equivalent.

TABLE 2.

Free energy differences for the exchange PS/PC/PS → PS/PS/PC in a DPPC membrane in the presence of calcium ions.

| ΔG / (kcal/mol) [ΔG0.1–0.0 / ΔG1.0–0.9]

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI method

|

||||

| Run No.* | Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | Scheme 3 | FEP method |

| 1 | −7.78 [47.39/ −49.59] | −7.52 [57.39/ −59.34] | −6.95 [120.71/ −122.09] | −5.01 [69.67/ −70.65] |

| 2 | −7.26 [43.95/ −44.83] | −7.82 [51.75/ −53.20] | −9.78 [103.29/ −106.70] | −5.67 [73.04/ −72.10] |

| 3 | −8.01 [39.19/ −41.40] | −8.82 [47.17/ −50.19] | −12.82 [98.50/ −105.53] | −9.80 [55.67/ −54.51] |

| Mean ± SD† | −7.68 (0.38) | −8.05 (0.68) | −9.85 (2.96) | −6.83 (2.60) |

Five points (λ = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9) were used to calculate the free energy differences using the FEP and TI methods.

The values in square brackets are the  and

and  end-point contributions to the free energy differences, respectively.

end-point contributions to the free energy differences, respectively.

Runs 1 and 2 correspond to the calculation of the free energy in the lower-layer and the upper-layer systems, respectively. Run 3 corresponds to the lower-layer system as well, but different initial conditions were set up for the dynamics. The lipid membrane is symmetric.

The standard deviation was computed as  and it is given in parentheses; n is the number of runs.

and it is given in parentheses; n is the number of runs.

The picture emerging from the analysis of the PS headgroup orientation (see above distribution of the  ) shows that the PSs in the two layers were sampling two neighboring substates of the system. However, the calculated ΔG values for both layers (Runs 1 and 2 in Table 2) are essentially the same within the error limit, reinforcing the overall conclusion that the association of two PSs in the presence of Ca2+ ions is favorable. Although this study did not explore extensively the dependence of the free energy on the relative configurations of the lipids, it appears that it is not strongly dependent on the particular headgroup orientation. This is in clear distinction from the simulations in the absence of Ca2+, where the free energy shows a much stronger dependence on the particular arrangement of PS headgroups in the lipid membrane (Table 1).

) shows that the PSs in the two layers were sampling two neighboring substates of the system. However, the calculated ΔG values for both layers (Runs 1 and 2 in Table 2) are essentially the same within the error limit, reinforcing the overall conclusion that the association of two PSs in the presence of Ca2+ ions is favorable. Although this study did not explore extensively the dependence of the free energy on the relative configurations of the lipids, it appears that it is not strongly dependent on the particular headgroup orientation. This is in clear distinction from the simulations in the absence of Ca2+, where the free energy shows a much stronger dependence on the particular arrangement of PS headgroups in the lipid membrane (Table 1).

The free energy derivative and the cumulative free energy change  as a function of λ are shown in Fig. 6, A and B. The free energy resulting from the different schemes of TI and FEP varies between −6.8 and −9.9 kcal/mol. These mean value extremes correspond to the FEP method and Scheme 2 of the TI method, respectively. Similarly to the simulations of the membrane without calcium, the value of the free energy difference obtained from FEP is also included in the interval where the values of the free energy using TI are found, that is,

as a function of λ are shown in Fig. 6, A and B. The free energy resulting from the different schemes of TI and FEP varies between −6.8 and −9.9 kcal/mol. These mean value extremes correspond to the FEP method and Scheme 2 of the TI method, respectively. Similarly to the simulations of the membrane without calcium, the value of the free energy difference obtained from FEP is also included in the interval where the values of the free energy using TI are found, that is,  kcal/mol. Table 2 also lists the end-point contributions to the free energy difference at

kcal/mol. Table 2 also lists the end-point contributions to the free energy difference at  and

and  The sum of both end-point contributions to the free energy is negative for all runs and schemes of TI.

The sum of both end-point contributions to the free energy is negative for all runs and schemes of TI.

FIGURE 6.

(A) TI integrand for the transition PS/PC/PS → PS/PS/PC. Five points (λ = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9) were used to calculate the free energy differences in a lipid membrane with calcium ions. Diamonds, circles, and triangles correspond to run 1 (lower layer), 2 (upper layer), and 3 (lower layer with different initial conditions), respectively. (B) Free energy differences showing the similarity on the final values (see Table 2).

The decomposition of the free energy into its bonded (bond, angle, Urey-Bradley, dihedral and improper angles) and nonbonded terms (van der Waals and electrostatics) shows that the contributions of the bonded terms to the free energy difference are small with values ranging between −0.43 and 0.47 kcal/mol. Bond terms and improper torsions contribute negative values and the remaining terms are positive. The main contribution to the free energy difference comes from the nonbonded terms, dominated by electrostatics (ΔGelect = −5.66 kcal/mol). This is not surprising because the free energy is dominated by the interaction between the two negative charges of the PS headgroups and the Ca2+ ions. Since decompositions of the free energy are path dependent the results above are specific to the path chosen for the free energy calculation. However, the difference among the bonded and nonbonded (van der Waals and electrostatic) terms are large enough to have general significance. They also agree with the intuitive picture of headgroup interactions in the presence of Ca2+ ions.

Role of lipid-lipid interactions in cluster formation

The ensemble generated in our simulation can serve in assessing whether lipid-lipid interactions contribute to nonideal mixing and cluster formation. The theoretical model of Huang et al. (21) writes the total potential energy of a triangular lattice of PC/PS membrane as made up of two types of terms: the long range electrostatic interactions between PS molecules,  and the short-range nonelectrostatic interactions between the lipids. Thus, within the lattice approximation the total potential energy is:

and the short-range nonelectrostatic interactions between the lipids. Thus, within the lattice approximation the total potential energy is:

|

(7) |

where Z is the number of nearest neighbors and UPS-PS, UPC-PC, and UPC-PS are the interaction energies between the contacting lipids. ΔEm is the nonelectrostatic excess mixing energy of both lipids, which is defined as:

|

(8) |

The first term in Eq. 7 is constant so it does not contribute to the nonideal mixing. The mixing behavior thus depends entirely on the last two terms of which the ΔEm controls the mixing behavior at constant  If ΔEm is positive the interaction between like lipids is more attractive reducing the number of PS-PC contacts and leading to the formation of clusters. In contrast, for ΔEm negative the two types of lipids prefer to interact with each other and the system will mix uniformly to increase the number of PS-PC contacts. Sufficiently large ΔEm will overcome the electrostatic repulsion leading to cluster formation. Huang et al. (21) show that at

If ΔEm is positive the interaction between like lipids is more attractive reducing the number of PS-PC contacts and leading to the formation of clusters. In contrast, for ΔEm negative the two types of lipids prefer to interact with each other and the system will mix uniformly to increase the number of PS-PC contacts. Sufficiently large ΔEm will overcome the electrostatic repulsion leading to cluster formation. Huang et al. (21) show that at  = 0.4 nonideal mixing is observed at ΔEm of 0.6 kT and that at ΔEm = 0.4 kT nonideal mixing appears throughout the entire range of χPS. Thus, an estimation of ΔEm from the simulation results can indicate whether the PS/PC ensemble explored here shows nonideal mixing.

= 0.4 nonideal mixing is observed at ΔEm of 0.6 kT and that at ΔEm = 0.4 kT nonideal mixing appears throughout the entire range of χPS. Thus, an estimation of ΔEm from the simulation results can indicate whether the PS/PC ensemble explored here shows nonideal mixing.

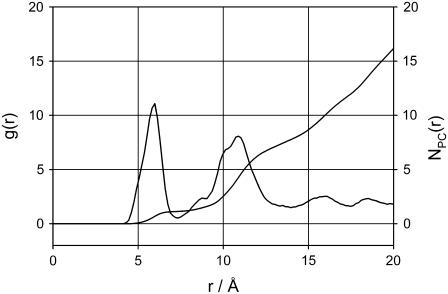

We calculated ΔEm by averaging the PS-PS, PC-PC, and PC-PS interaction energies over the simulation. In our calculations we only include the headgroups because both lipids have the same hydrocarbon tails. The potential energy terms for PC-PC and PC-PS were averaged over pairwise combinations present in the system. The PS-PS potential energy term was calculated from a simulation of the membrane with a Ca2+ to provide a close contact PS-PS pair. Since our PS/PC membrane is not a two-dimensional ideal lattice the value of ΔEm( ) was calculated as a function of the number of neighbors. To evaluate the proper number of neighbors for averaging the interaction energies, we have calculated the radial distribution function (rdf) of PC headgroups (Fig. 7) The integration of the rdf shows a cluster of two PCs separated at 6 Å for the P–P distance. The major peak in the rdf is spread between 12 and 14 Å and consists of six to eight neighbors. We thus calculated the average UPC-PC using progressively increasing number of neighbors starting with six.

) was calculated as a function of the number of neighbors. To evaluate the proper number of neighbors for averaging the interaction energies, we have calculated the radial distribution function (rdf) of PC headgroups (Fig. 7) The integration of the rdf shows a cluster of two PCs separated at 6 Å for the P–P distance. The major peak in the rdf is spread between 12 and 14 Å and consists of six to eight neighbors. We thus calculated the average UPC-PC using progressively increasing number of neighbors starting with six.

FIGURE 7.

Radial distribution function for the P atoms of the PC headgroup lipids and the number of neighbors (PC) as a function of the phosphorous atom distance (P–P distance).

The results in Table 3 show that ΔEm is always positive and increases from 0.30 to 0.63 kT for an increasing number of neighbors. This clearly reflects a tendency of cluster formation, which confirms the small cluster of two PCs observed in the rdf.

TABLE 3.

Nonelectrostatic excess mixing energy, ΔEm

* (kT) * (kT)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of neighbors

|

||||

| Lipid pairs | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| PC-PC | −1.59 | −1.43 | −1.21 | −1.07 |

| PC-PS | −1.82 | −1.57 | −1.38 | −1.22 |

| PS-PS† | −2.64 | −2.64 | −2.64 | −2.64 |

| ΔEm / (kT) | 0.30 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.63 |

is the pair average van der Waals interaction energy calculated from a 500-ps trajectory.

is the pair average van der Waals interaction energy calculated from a 500-ps trajectory.

The fixed value was obtained from a simulation of the PS/PC system in the presence of Ca2+.

It is important to comment on the value of UPS-PS that we have used to estimate ΔEm. This system contains two PSs embedded in an ensemble of 22 PCs, which allows for a good estimate of the UPC-PC and UPC-PS terms. The relatively low  prevents a similar investigation of the dependence of UPS-PS on the number of members. However, the distribution of PS-PS distances obtained from the simulation extends all the way to 12 Å. Thus, we have used the average UPS-PS to estimate the ΔEm. Equation 8 and the results in Table 3 clearly set the limit of UPS-PS that is required for the appearance of nonideal mixing as a function of the number of neighbors. The value that we estimate from our simulations always satisfies this limit. Thus, it appears that nonideal mixing is a realistic possibility in PS/PC mixed lipid systems.

prevents a similar investigation of the dependence of UPS-PS on the number of members. However, the distribution of PS-PS distances obtained from the simulation extends all the way to 12 Å. Thus, we have used the average UPS-PS to estimate the ΔEm. Equation 8 and the results in Table 3 clearly set the limit of UPS-PS that is required for the appearance of nonideal mixing as a function of the number of neighbors. The value that we estimate from our simulations always satisfies this limit. Thus, it appears that nonideal mixing is a realistic possibility in PS/PC mixed lipid systems.

CONCLUSIONS

We have simulated a DPPS/DPPC bilayer mixture with the aim of calculating the free energy of association between two PSs in the environment of PCs. The importance of the behavior of mixed lipid systems is that divalent cations such as Ca2+ or proteins that associate with the lipid lead to lateral demixing of PS and PC. Thus, the free energy of peripheral protein association with charged membranes composed of zwitterionic and acidic lipids mixture may depend on the nonideal nature of the lipid system presented at the initial conditions.

Our results suggest that the association between two PSs in the environment of PCs in the presence of Ca2+ ions is thermodynamically favorable, which agrees with previous studies on domain separation mediated by Ca2+ ions. Furthermore, the nonelectrostatic interactions between the lipid headgroups lead to clustering. A careful description of the initial conditions of the mixed lipids is therefore essential for a proper evaluation of the thermodynamics of protein-lipid association.

Acknowledgments

Y. Rodríguez dedicates this manuscript in memory of his father, Jacinto. Y. R. is grateful to Antonio S. Torralba for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript, and to Emmanuel Giudice and Tatyana Gindin for technical assistance at the beginning of this work. We are also grateful to Sonia Jorge, who made important contributions at the beginning of this project.

This work was supported by Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia of Spain through a postdoctoral fellowship to Y.R.

References

- 1.Mann, K. G. 1999. Biochemistry and physiology of blood coagulation. Thromb. Haemost. 82:165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenny, N. S., and K. Mann. G. 2003. Coagulation cascade: an overview. In Thrombosis and Hemorrhage, 3rd Ed. J. Loscazo and A. I. Schafer, editors. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, New York. 1–21.

- 3.Davie, E. W., K. Fujikawa, and W. Kisiel. 1991. The coagulation cascade: initiation, maintenance, and regulation. Biochemistry. 30:10363–10370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jesty, J., and Y. Nemerson. 1995. The pathways of blood coagulation. In Williams Hematology, 5th Ed. E. Beutler, M. A. Lichtman, B. S. Coller, and T. J. Kipps, editors. McGraw-Hill, New York. 1227–1238.

- 5.Lentz, B. R. 2003. Exposure of platelet membrane phosphatidylserine regulates blood coagulation. Prog. Lipid Res. 42:423–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furie, B., and B. C. Furie. 1990. Molecular basis of vitamin K-dependent γ-carboxylation. Blood. 75:1753–1762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang, M., A. C. Rigby, X. Morelli, M. A. Grant, G. Huang, B. Furie, B. Seaton, and B. C. Furie. 2003. Structural basis of membrane binding by Gla domains of vitamin K-dependent proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald, J. F., A. M. Shah, R. A. Schwalbe, W. Kisiel, B. Dahlback, and G. L. Nelsestuen. 1997. Comparison of naturally occurring vitamin K-dependent proteins: correlation of amino acid sequences and membrane binding properties suggests a membrane contact site. Biochemistry. 36:5120–5127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhai, X., A. Srivastava, D. C. Drummond, D. Daleke, and B. R. Lentz. 2002. Phosphatidylserine binding alters the conformation and specifically enhances the cofactor activity of bovine factor Va. Biochemistry. 41:5675–5684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srivastava, A., J. F. Wang, R. Majumder, A. R. Rezaie, J. Stenflo, C. T. Esmon, and B. R. Lentz. 2002. Localization of phosphatidylserine binding sites to structural domains of factor Xa. J. Biol. Chem. 277:1855–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppaka, V., J. F. Wang, M. Banerjee, and B. R. Lentz. 1996. Soluble phospholipids enhance factor Xa-catalyzed prothrombin activation in solution. Biochemistry. 35:7482–7491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sankaram, M. B., and D. Marsh. 1993. Protein-lipid interactions with peripheral membrane proteins. In New Comprehensive Biochemistry, Vol. 25. Protein-Lipid Interactions. A. Watts, editor. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 127–162.

- 13.Ben-Tal, N., B. Honig, R. M. Peitzsch, G. Denisov, and S. McLaughlin. 1996. Binding of small basic peptides to membranes containing acidic lipids: theoretical models and experimental results. Biophys. J. 71:561–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Tal, N., B. Honig, C. Miller, and S. McLaughlin. 1997. Electrostatic binding of proteins to membranes. Theoretical predictions and experimental results with charybdotoxin and phospholipid vesicles. Biophys. J. 73:1717–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth, C. M., J. E. Sader, and A. M. Lenhoff. 1998. Electrostatic contribution to the energy and entropy of protein adsorption. J. Colloid Interf. Sc. 203:218–221. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray, D., A. Arbuzova, G. Hangyas-Mihalyne, A. Gambhir, N. Ben-Tal, B. Honig, and S. McLaughlin. 1999. Electrostatic properties of membranes containing acidic lipids and adsorbed basic peptides: theory and experiment. Biophys. J. 77:3176–3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denisov, G., S. Wanaski, P. Luan, M. Glaser, and S. McLaughlin. 1998. Binding of basic peptides to membranes produces lateral domains enriched in the acidic lipids phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate: an electrostatic model and experimental results. Biophys. J. 74:731–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heimburg, T., B. Angerstein, and D. Marsh. 1999. Binding of peripheral proteins to mixed lipid membranes: effect of lipid demixing upon binding. Biophys. J. 76:2575–2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.May, S., D. Harries, and A. Ben-Shaul. 2000. Lipid demixing and protein-protein interactions in the adsorption of charged proteins on mixed membranes. Biophys. J. 79:1747–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heimburg, T., and D. Marsh. 1995. Protein surface-distribution and protein-protein interactions in the binding of peripheral proteins to charged lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 68:536–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, J., J. E. Swanson, A. R. Dibble, A. K. Hinderliter, and G. W. Feigenson. 1993. Nonideal mixing of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine in the fluid lamellar phase. Biophys. J. 64:413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dijck, P. W., B. de Kruijff, A. J. Verkleij, L. L. van Deenen, and J. de Gier. 1978. Comparative studies on the effects of pH and Ca2+ on bilayers of various negatively charged phospholipids and their mixtures with phosphatidylcholine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 512:84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reviakine, I., A. Simon, and A. Brisson. 2000. Effect of Ca2+ on the morphology of mixed DPPC-DOPS supported phospholipid bilayers. Langmuir. 16:1473–1477. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luna, E. J., and H. M. Mcconnell. 1977. Lateral phase separations in binary-mixtures of phospholipids having different charges and different crystalline-structures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 470:303–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson, K., and D. Papahadjopoulos. 1975. Phase transitions and phase separations in phospholipid membranes induced by changes in temperature, pH, and concentration of bivalent cations. Biochemistry. 14:152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hincha, D. K. 2003. Effects of calcium-induced aggregation on the physical stability of liposomes containing plant glycolipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1611:180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilschut, J., N. Duzgunes, R. Fraley, and D. Papahadjopoulos. 1980. Studies on the mechanism of membrane fusion: kinetics of calcium ion induced fusion of phosphatidylserine vesicles followed by a new assay for mixing of aqueous vesicle contents. Biochemistry. 19:6011–6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mora, M., F. Mir, M. A. de Madariaga, and M. L. Sagrista. 2000. Aggregation and fusion of vesicles composed of N-palmitoyl derivatives of membrane phospholipids. Lipids. 35:513–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart, R. J., and J. M. Boggs. 1993. A carbohydrate-carbohydrate interaction between galactosylceramide-containing liposomes and cerebroside sulfate-containing liposomes: dependence on the glycolipid ceramide composition. Biochemistry. 32:10666–10674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koshy, K. M., and J. M. Boggs. 1996. Investigation of the calcium-mediated association between the carbohydrate head groups of galactosylceramide and galactosylceramide I3 sulfate by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 271:3496–3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koshy, K. M., J. Y. Wang, and J. M. Boggs. 1999. Divalent cation-mediated interaction between cerebroside sulfate and cerebrosides: an investigation of the effect of structural variations of lipids by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Biophys. J. 77:306–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leach, A. R. 2001. Four challenges in molecular modelling: free energies, solvation, reactions and solid-state defects. In Molecular Modelling: Principles and Applications, 2nd Ed. Prentice Hall, New York. 563–639.

- 33.Mezei, M., and D. L. Beveridge. 1986. Free energy simulations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 482:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roux, B. 2004. Building a configuration for a membrane/protein system. http://thallium.bsd.uchicago.edu/rouxlab/method.html. [Online].

- 35.De Loof, H., S. C. Harvey, J. P. Segrest, and R. W. Pastor. 1991. Mean field stochastic boundary molecular dynamics simulation of a phospholipid in a membrane. Biochemistry. 30:2099–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pastor, R. W., R. M. Venable, and M. Karplus. 1991. Model for the structure of the lipid bilayer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:892–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venable, R. M., Y. Zhang, B. J. Hardy, and R. W. Pastor. 1993. Molecular dynamics simulations of a lipid bilayer and of hexadecane: an investigation of membrane fluidity. Science. 262:223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jedlovszky, P., and M. Mezei. 1999. Grand canonical ensemble Monte Carlo simulation of a lipid bilayer using extension biased rotations. J. Chem. Phys. 111:10770–10773. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feller, S. E., and A. D. MacKerell. 2000. An improved empirical potential energy function for molecular simulations of phospholipids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:7510–7515. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, R. W. Impey, and M. L. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryckaert, J. P., G. Ciccotti, and H. J. C. Berendsen. 1977. Numerical integration of Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooks, B. R., R. E. Bruccoleri, B. D. Olafson, D. J. States, S. Swaminathan, and M. Karplus. 1983. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mezei, M. 2004. MMC: Monte Carlo program for simulation of molecular assemblies. http://inka.mssm.edu/∼mezei/mmc. [Online].

- 44.Pearlman, D. A. 1994. A comparison of alternative approaches to free energy calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 98:1487–1493. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Resat, H., and M. Mezei. 1993. Studies on free energy calculations. 1. Thermodynamic integration using a polynomial path. J. Chem. Phys. 99:6052–6061. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simonson, T., G. Archontis, and M. Karplus. 1997. Continuum treatment of long-range interactions in free energy calculations. Application to protein-ligand binding. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:8349–8362. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tidor, B., and M. Karplus. 1991. Simulation analysis of the stability mutant R96H of T4 lysozyme. Biochemistry. 30:3217–3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michielin, O., and M. Karplus. 2002. Binding free energy differences in a TCR-peptide-MHC complex induced by a peptide mutation: a simulation analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 324:547–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng, J., M. Fridman, H. Maruta, H. R. Treutlein, and T. Simonson. 1999. Protein-protein recognition: an experimental and computational study of the R89K mutation in Raf and its effect on Ras binding. Protein Sci. 8:50–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Archontis, G., T. Simonson, D. Moras, and M. Karplus. 1998. Specific amino acid recognition by aspartyl-tRNA synthetase studied by free energy simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 275:823–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisstein, E. W. 2004. Legendre-Gauss quadrature. In MathWorld: A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/legendre-gaussquadrature.html. [Online].

- 52.Simonson, T. 1993. Free energy of particle insertion. An exact analysis of the origin singularity for simple liquids. Mol. Physi. 80:441–447. [Google Scholar]

- 53.White, S. H., and M. C. Wiener. 1996. The liquid-crystallographic structure of fluid lipid bilayer membranes. In Biological Membranes: A Molecular Perspective from Computation and Experiment. K. M. Merz and B. Roux, editors. Birkhäuser, Boston, MA. 127–144.

- 54.Sachs, J. N., H. Nanda, H. I. Petrache, and T. B. Woolf. 2004. Changes in phosphatidylcholine headgroup tilt and water order induced by monovalent salts: molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 86:3772–3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandit, S. A., D. Bostick, and M. L. Berkowitz. 2003. Mixed bilayer containing dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine and dipalmitoylphosphatidylserine: lipid complexation, ion binding, and electrostatics. Biophys. J. 85:3120–3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]