Abstract

It is known that the action of general anesthetics is proportional to their partition coefficient in lipid membranes (Meyer-Overton rule). This solubility is, however, directly related to the depression of the temperature of the melting transition found close to body temperature in biomembranes. We propose a thermodynamic extension of the Meyer-Overton rule, which is based on free energy changes in the system and thus automatically incorporates the effects of melting point depression. This model accounts for the pressure reversal of anesthesia in a quantitative manner. Further, it explains why inflammation and the addition of divalent cations reduce the effectiveness of anesthesia.

INTRODUCTION

More than 100 years ago, Hans Meyer in Marburg (1) and Charles Ernest Overton in Zürich (2) independently found that the action of general anesthetics is related to their partition coefficient between water and olive oil. Overton performed experiments on tadpoles and recorded the critical drug concentration, ED50, at which they stopped swimming. Assuming that the solubility of these anesthetics in olive oil is proportional to that in biomembranes, he suggested that this critical concentration corresponded to a fixed concentration in biomembranes. The Meyer-Overton rule can be expressed as [ED50] × P = const, where P is the partition coefficient of the anesthetic drug between membranes and water. Small molecules, as different as nitrous oxide, chloroform, octanol, diethylether, procaine, and even the noble gas xenon, all act as anesthetics. Overton noted that this action is completely unspecific, i.e., dependent only on the solubility of the anesthetic in oil and independent of its chemical nature. Surprisingly, this finding is still valid for general and local anesthetics (2–5) but remains unexplained. Overton concluded that this nonspecificity requires a single mechanism based on physical chemistry and not on the molecular structure of the drugs. Although the close relation between anesthetic effect and solubility in lipids led many scientists to believe that anesthetic action is lipid-related, no model was proposed by Meyer and Overton or by later research. It is known, however, that lipid-melting transitions are lowered in the presence of anesthetics. This has been related to the anesthetic function (6,7).

In the absence of a satisfactory physiological membrane mechanism, many others prefer to view the action of anesthetics as due to specific effects on proteins, e.g., sodium channels or luciferase (8–10). Since anesthetics act on nerves and the Hodgkin-Huxley theory for the action potential is based on the opening and closing of ion channels, it seems natural to attribute the action of anesthetics to interactions with these channels. Some anesthetics show a stereospecificity indicating that the effective anesthetic concentration (ED50) is different for the two chiral forms even though the partition coefficient is not affected to the same degree (11). In this regard, however, we note that lipid molecules are also chiral. While it is widely believed that local anesthetics are sodium channel blockers, a satisfactory general model of how anesthetics act on proteins is again lacking. The action of anesthetics is still mysterious. Some lipid and protein theories on anesthesia are reviewed in the literature (8,12).

The general absence of specificity and the strong correlation between solubility in lipid membranes and anesthetic action seems to speak against specific binding and a protein mechanism. On the other hand, there is clear evidence that the action of some proteins is influenced by anesthetics. Data on the influence of anesthetics on luciferase and on Na- and K-channels are summarized in Firestone et al. (13) and suggest that the action of lipids and that of proteins are coupled in some simple manner. Cantor has thus proposed that all membrane-soluble substances alter the lateral pressure in the hydrocarbon region and thereby influence the structure of proteins (14–16). Lee proposed a coupling of protein function to the transition temperature of a lipid annulus at the protein interface (17). While such mechanisms may provide a control of protein function, it is nevertheless remarkable that all animals are affected to the same degree by anesthetics, suggesting that anesthetic action is largely independent of the specific protein composition of membranes. (See (2), foreword to the English edition.) In addition to their effect on nerves, anesthetics also change membrane properties such as permeability and/or the hemolysis of erythrocytes (5,13). This indicates the need for a more general view of anesthetic action.

In this article, we focus on a thermodynamic description of general anesthesia based on lipid properties. We recognize that this can seem heretical given the dominance of the ion channel picture. Nevertheless, there are a variety of reasons for considering a macroscopic thermodynamic view. The striking fact that noble gases can act as general anesthetics speaks against specific binding to macromolecules. In particular, the Meyer-Overton rule would require all anesthetics to have exactly the same partition coefficient between lipid membrane and protein binding sites for all relevant proteins. It is difficult to imagine that nature provides binding sites for such a variety of molecules on the same protein in precisely such a manner that binding affinity is independent of chemical nature. (It is unlikely that one protein provides binding sites for all anesthetics. Therefore, if a protein picture was to be maintained one has to abandon a unique mechanism for anesthesia (Keith Miller, Harvard Medical School, private communication, 2006.)) An acceptable description should account for this evident lack of specificity, and this suggests the utility of thermodynamic arguments. Moreover, it is to be emphasized that thermodynamics is not inimical to microscopic (e.g., ion-channel) descriptions of the same phenomena. No one would claim, for example, that the manifest successes of thermodynamics in describing the properties of real gases in any way contradict the fact that they are composed of interacting atoms. Thermodynamics rather recognizes that many macroscopic phenomena are independent of such microscopic details and that a large number of microscopic systems can display features, which are both qualitatively and quantitatively susceptible to more generic methods. Precisely the absence of detail means that thermodynamic approaches are often capable of making testable quantitative predictions, which are often inaccessible to or obscured by more microscopic models. Thus, we wish to propose a simple thermodynamic explanation of the Meyer-Overton rule based on the well-known physical chemical phenomenon of freezing-point depression. We will show that this picture has the benefit of providing an immediate and intuitive picture for the pressure reversal of anesthesia as a consequence of the pressure-induced elevation of the melting point in lipid membranes and can explain the effects of inflammation and divalent cations on anesthetic action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Birmingham, AL) and used without further purification. Octanol was purchased from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). Multilamellar lipid dispersions (5 mM, buffer: 2 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, octanol concentration adjusted) were prepared by vortexing the lipid dispersions above the phase transition temperature of the lipid. We also performed experiments with halothane and other anesthetics that yielded results similar to those of octanol. These data are not shown here.

Escherichia coli bacteria (XL1 blue with tetracycline resistance) and Bacillus subtilis were grown in a LB-medium at 37°C. The bacterial membranes were then disrupted in a French Press at 1200 bar (Gaulin, APV Homogeniser, Lübeck, Germany) and centrifuged at low speed in a desk centrifuge to remove solid impurities. The remaining supernatant was centrifuged at high speed in a Beckman ultracentrifuge (50,000 rpm) in a Ti70 rotor to separate the membranes from soluble proteins and nucleic acids. This membrane fraction was measured in a calorimeter. Lipid melting peaks and protein unfolding can easily be distinguished in pressure calorimetry due to their characteristic pressure dependences. The pressure dependence of lipid transitions is much higher than that of proteins and nearly independent of the lipid or lipid mixture (19). Further, in contrast to lipid transitions, the heat unfolding of the proteins is not reversible. More details regarding the E. coli measurements are given in an MSc thesis (20) and will be published elsewhere.

Heat capacity profiles were obtained using a VP-scanning calorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) at scan rates of 5°/h (lipid vesicles) and 30°/h for E. coli membranes.

To calculate the theoretical heat capacity profiles we used ideal solution theory, described in Lee (21). It was assumed that the anesthetic is ideally miscible with the fluid phase and immiscible in the gel phase. These assumptions are in agreement with experiment. Due to the partition coefficient in the membrane most of the anesthetic is found in the membrane (P = 200 for DPPC membranes (22)) if the amount of the aqueous phase is small. Under such conditions, the anesthetic concentration in the fluid phase changes when lowering the temperature below the onset of the melting transition. The chemical potentials of the gel and the fluid lipid membrane are given by

|

(1) |

where xA is the molar fraction of anesthetics in the membrane. The values  and

and  are the standard state chemical potentials that obey the relation

are the standard state chemical potentials that obey the relation

|

(2) |

with the excess enthalpy of the transition, ΔH, and the melting temperature, Tm. With these assumptions, one can calculate phase boundaries and melting point depression (see next section). Using the lever rule one can deduce the relative fractions of gel and fluid phase as a function of temperature (21). When the fraction of fluid phase, ffluid, is multiplied with the excess melting enthalpy, ΔH, one obtains the enthalpy as a function of temperature, ΔH(T) = ffluid × ΔH. The excess heat capacity is the derivative of this function.

THEORY AND RESULTS

The unspecific effect of anesthetics and other small solutes on lipid melting transitions

Biological membranes are known to undergo a phase transition from a low-temperature solid-ordered (SO or gel) phase to a liquid-disordered (LD or fluid) phase at temperatures slightly below physiological temperature. This transition involves a volume change of ≈4% and an area change of ≈25%. It is also known empirically that nerve pulses are accompanied by density and heat (23) changes consistent with forcing the lipid mixture through ≈85% of this phase transition (24,25). When supplemented by the empirical observation that the sound velocity in lipid mixtures increases with frequency, this fact leads to the robust prediction that localized piezo-electric pulses (or “solitons”) can propagate stably in biological membranes (26,27). The lipid-melting transition is essential for the existence of solitons. In the transition from the LD to the SO phase, membranes become more compressible and also permeable for ions and molecules (28–30). The biological membrane thus resembles a spring that becomes softer upon compression. This nonlinearity is necessary for the formation of solitons, which can propagate in cylindrical membranes without distortion even in the presence of significant noise. Such a description can account naturally for the reversible heat and mechanical features of nerve pulses and also predicts a pulse propagation velocity of ≈100 m/s, which is comparable to that in myelinated nerves.

Given the existence of a lipid phase transition and its possible biological relevance, it is tempting to speculate that it plays a functional role in unspecific anesthetic effects and that it is central to understanding the Meyer-Overton rule. The basis for such speculation is elementary. The introduction of any solute (i.e., anesthetic) into membranes leads to a lowering of the temperature of the melting transition which is proportional to the molar concentration of the solute and largely independent of its chemical nature.

Small molecules, peptides and proteins are not in general readily soluble in the SO-phase due to its crystalline structure. They are much more soluble in the LD phase. This leads to a reduction of melting points, demonstrated in Fig. 1 for the artificial lipid DPPC in the presence of the local anesthetic octanol. This effect is known as freezing point depression (31). For example, the solubility of NaCl is high in water and low in ice. Thus, salt lowers the freezing point of water. This effect is due to the difference in mixing entropy of the ions in water and ice. For low solute concentrations and with the reasonable assumptions of perfect miscibility of an anesthetic in the LD phase and immiscibility in the SO phase, one arrives at the well-known relation between melting point depression and solute concentration (31),

|

(3) |

where xA is the molar fraction of anesthetic in the membrane, ΔH is the lipid-melting enthalpy (∼35 kJ/mol for DPPC), and Tm is the lipid-melting temperature (314.3 K for DPPC, and 295 K for native E. coli membranes). An anesthetic concentration of 1 mol % in the fluid membrane leads to ΔTm = −0.24 K. Freezing point depression has been discussed in the context of anesthesia before, e.g., by Kaminoh et al. (25).

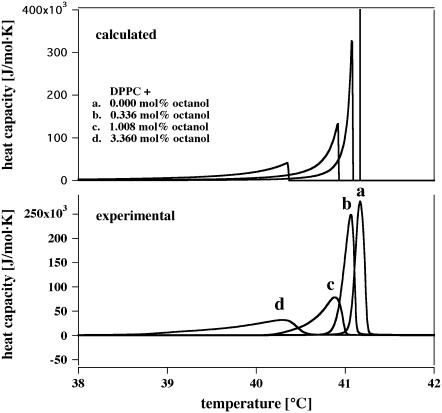

FIGURE 1.

The effect of octanol on the phase transition of DPPC vesicles. (Bottom) Calorimetric data with various octanol concentrations in the membrane. (Top) Calorimetric profiles calculated for the same membrane concentrations of a solute assuming ideal mixing in the fluid phase and no mixing in the gel phase. The high temperature end of the transition profile corresponds to the temperature calculated for melting point depression. The calculation assumes a finite bulk fluid phase. This leads to an accumulation of anesthetics in the fluid phase as the temperature is lowered and to an asymmetric broadening of the cp profile.

The heat capacity at constant pressure, cP, can be calculated as a function of temperature for various solute concentrations using ideal solution theory (21) with the assumption of complete insolubility in the solid phase (Fig. 1, top). The peak in this figure corresponds to the phase transition. We have assumed a small amount of the water phase (as used experimentally) and an accumulation of anesthetics in the fluid phase. This leads to the broadening of the profiles, which are remarkably similarity to experimental results obtained for DPPC vesicles in the presence of various anesthetic concentrations as shown in the lower panel. The quantitative agreement between the experimentally obtained heat capacity profiles in the presence of anesthetics and those calculated justifies the assumptions made and supports the overall notion that anesthetics change the thermodynamic properties of membranes in a simple manner. We will make use of this fact below.

The anesthetic concentration in membranes at critical dosage can be calculated using the partition coefficient, P, extracted from data collected in Firestone et al. (13) for water-soluble anesthetics and tadpole anesthesia. Solvents include octanol/water, PC, or egg-PC/water, and erythrocyte or PC+cholesterol/water. This data includes 28 separate solute/solvent combinations for which the partition coefficients vary by a factor of 7000. Log-log plots of P versus ED50, defined as the concentration in molar units at which 50% of tadpoles are immobilized, reveal that the data is consistent within error with a straight line of slope −1. The Meyer-Overton rule is fulfilled independent of the reference system. Additional modern confirmation of the Meyer-Overton rule can be found in Kharakoz (7) and Overton (2) (foreword to the English edition). The partition coefficient of membranes high in cholesterol is smaller than that of cholesterol-free membranes. Since nerves have a relatively low cholesterol content (i.e., <10%), we will use the partition coefficient in PC or Egg-PC as a reference in the following. The assumption of linear dependence of anesthesia on the partition coefficient is an idealization. Characteristic deviations are roughly a factor of two (comparable to that found for different chiral forms) and are not large given the full range of partition coefficients spanned by the data. We use only data for tadpole narcosis, where the signature of anesthesia is unambiguous. A least-squares fit yields

|

(4) |

for PC or egg-PC/water.

The molar fraction of anesthetics in the fluid membrane at anesthetic dose is readily determined using Eq. 4 as

|

(5) |

where the molar volume of fluid lipids, Vl, is taken here to be 0.750 l/mol. This yields a membrane concentration of ∼2.6 mol % of anesthetics in egg-PC membranes independent of anesthetic. According to Eq. 3, this corresponds to ΔTm ≈ −0.60 K at anesthetic dose for tadpoles. Kharakoz (7) obtained ΔTm ≈ −0.53 K directly from data for a series of alkanols, which corresponds to an anesthetic concentration of 2.3 mol % in membranes. The striking agreement of these results indicates that the freezing point depression of Eq. 3 provides an adequate description of the experimental shifts in Tm.

The phenomenon of melting point depression, illustrated here for octanol, allows us to reexpress the Meyer-Overton rule as: At critical anesthetic dose, all anesthetics lower the melting temperatures of lipid membranes by exactly the same amount. Deviations from the rule usually indicate that the assumptions of ideal mixing in the fluid phase and/or no mixing in the solid lipid phase are not quantitatively correct. In particular, small noble gases atoms are also likely to dissolve in the solid lipid phase. Large anesthetics may display phase behavior on their own, i.e., they may not mix ideally in fluid lipids. In the following, we will be concerned with anesthetics that do follow the Meyer-Overton rule. It is our expectation that the thermodynamic consequences of Cantor's model (14,15,32) will be consistent with our picture.

The effect of pressure on transitions

Anesthetics action can be reversed by hydrostatic pressure (33). In tadpoles, a bulk pressure of 140–350 bars reverses the action of 3–6 vol % ethanol narcosis (34). It has been suggested that this effect is related to the chain melting transition of lipid membranes (21,35–37). Melting transitions move to higher temperatures with bulk pressure, Δp, due to the fact that the volume of membranes in the SO phase is reduced by ∼4%. The shift is given as

|

(6) |

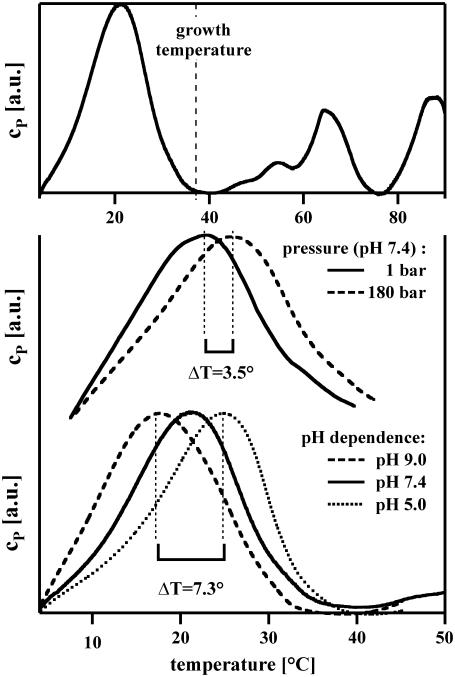

This is related to, but more specific than, the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. Here, γv = 7.8 × 10−10 m2/N is constant within errors for a variety of artificial and biological membranes (19,38). See also Fig. 2. Luciferase, which is regarded as a model protein for general anesthesia, does not display pressure reversal (39).

FIGURE 2.

Heat capacity profiles of native E. coli membranes. (Top) At 37°C. The growth temperature is indicated. The large peak below growth temperature corresponds to lipid melting. The smaller peaks above growth temperature correspond to protein unfolding. (Center) The heat capacity as a function of T at a hydrostatic pressure of 1 bar and 180 bar. The pressure-induced shift is ≈3.5 K. (Bottom) Heat capacities for the same membranes at various pH values. The transition temperature increases by ∼5.3 K when the pH is reduced from 7.4 to 5.0. Scans were halted at 40–43°C to prevent protein unfolding.

Free energy changes

Although the internal energy (or enthalpy) of a lipid membrane above the melting temperature is insensitive to changes in the lipid transition temperature, the associated free energy change has significant temperature dependence. Given the lipid melting enthalpy, ΔH, the entropy change associated with the transition is ΔS = ΔH/Tm. The difference between the free energies of the LD and SO phases at a body temperature T > Tm, ΔG = GLD − GSO, at constant pressure is thus given as

|

(7) |

which is explicitly sensitive to changes in T. Including the effects of anesthetics and a hydrostatic pressure, this difference in the Gibbs free energy for membranes becomes

|

(8) |

where Tm is the melting temperature of the membrane in the absence of anesthetics and Δp is the excess hydrostatic pressure. Obviously, Eq. 8 can be extended to include the effects of other relevant intensive thermodynamic variables such as the chemical potentials of hydrogen ions or calcium. The Meyer-Overton rule indicates that the free energy difference is increased by ≈5% by the addition of a critical dose of anesthetics. Since this energy must be supplied from chemical sources, it is natural to postulate that equal values of ΔG(T, Δp) will produce equal anesthetic effect. This postulate represents an extension of the Meyer-Overton rule, and Eq. 8 leads to a variety of specific and quantitative predictions regarding anesthetic action and other phenomena governed by this phase transition.

Pressure reversal of anesthesia

From Eq. 8, the pressure required to reverse the action of an anesthetic is

|

(9) |

The hydrostatic pressure required to reverse the action of anesthetics on the phase transition is 9.6 bar/mol % using the values of ΔH and Tm appropriate for DPPC.

Pressure reversal of anesthesia was first demonstrated by Johnson and Flagler (34). They anesthetized tadpoles in 3–6 vol % ethanol. A hydrostatic pressure of 140–350 bars was found to reverse anesthesia. According to Firestone et al. (13), 190 mM of ethanol (1.1 vol %) in the aqueous phase is necessary for tadpole narcosis. This means that ∼3–6 times the anesthetic ethanol concentration was used in Johnson and Flagler (34). The concentration of ethanol in the membrane in Johnson and Flagler's experiments was therefore 7.5–15 mol %. According to Eq. 3, these concentrations correspond to lowering Tm by 1.8–3.6 K. From Eq. 9, the pressure necessary to reverse this anesthetic effect is 72–148 bars. Considering the uncertainty of the partition coefficient for real biological membranes (which depends on the precise lipid mixture), this is remarkably close to the order of the values found by Johnson and Flagler (34). The fact the pressure increases Tm may be related to the observation that nerves fire spontaneously at high pressures (40).

Effects of pH and salts

Ions also change the free energy. Some 10% of the lipids of biological membranes are negatively charged, primarily on the inner membrane. At lower pH, some of these charges are protonated, and the electrostatic potential of the lipid membrane is reduced. Complete protonation increases the melting temperature by ∼20 K. The effects of pH and ionic strength on melting transitions have been carefully investigated by the literature (41,42). While these effects depend on the precise composition of the membrane and on ionic strength, they can be calculated using Debye-Hückel theory or determined empirically. For example, the temperature of the melting transition in native E. coli membranes (in the pH range between 5 and 9) is raised by ∼1.8° if pH is lowered by one unit (Fig. 2). This shift is approximately that which is produced by 72 bars hydrostatic pressure. Interestingly, it is known that inflammation leads to the failure of anesthesia. The related lowering of pH in inflamed tissue, i.e., on the order of 0.5 pH units (43), is widely assumed to be responsible. According to the above, the lowering of pH from 7 to 6.5 leads to ΔTm = +0.9 K, which is sufficient to reverse the action of anesthetics at the typical critical dose corresponding to ΔTm = −0.6 K.

Salts can also effect the melting transition through, e.g., the binding of divalent cations such as Mg2+ and Ca2+. These ions shift the melting temperatures of both charged and uncharged lipids to higher temperatures. The presence of such ions thus lowers the effectiveness of anesthetics, and appropriate functions of pH and salt concentration should be added to the right side of Eq. 8.

Temperature effects

Many processes in biology respond directly to temperature changes. Therefore it can be difficult to isolate individual temperature effects in vivo. It has been shown by Spyropoulos (44) and Kobatake et al. (45) that cooling can trigger the action potential whereas heating inhibits the nerve pulse. If the body temperature is changed from T to T + ΔT, the Gibbs free energy of the membrane also changes. The action of anesthetics can be reversed by changing body temperature by

|

(10) |

The effect of 2.6 mol % anesthetics is thus reversed by a 0.6 K reduction of the body temperature for the parameters of DPPC membranes. Interestingly, a well-known finding in clinical anesthesiology is hypothermia, i.e., the lowering of body-temperature during narcosis (46). This decrease partially compensates the effect of the transition temperature shift caused by anesthesia and suggests that the body tries to maintain a constant membrane state. Conversely, the same arguments say an equal rise in body temperature, e.g., by fever, should produce the same effects as a critical anesthetic does. Since this is not the case, a rise in body temperature must be accompanied by other thermodynamic changes which tend to counter this increase in the free energy difference (e.g., pH changes) if our thermodynamic picture is to be maintained. Further, a lowering of the temperature below the phase transition temperature (ΔT > −15 K) would lead to a complete cessation of nerve activity as found in clinical experiments (47). Note that the chemical composition of lipids can also change in response to changes in other thermodynamic variables. It is well documented that the lipid composition and the melting temperatures of bacterial membranes change as a response to changing growth temperature (e.g., (48). E. coli membranes grown at different temperature shift their melting temperatures to maintain a constant distance to growth temperature (unpublished data from our laboratory)).

CONCLUSION

We have proposed an elementary thermodynamic description of the action of general anesthesia according to which constant anesthetic effects are predicted whenever external thermodynamic variables (e.g., solute concentration, pressure, temperature, pH, and salt concentration) are adjusted to maintain constant values of the free energy difference between the liquid and gel phases of lipid membranes. Indeed, the effect of an anesthetic is intimately connected with its ability to depress the melting point of lipid membranes, which depends on its solubility in lipid mixtures but is otherwise independent of its chemical nature. The basis for the familiar Meyer-Overton rule thus lies in the thermodynamics of biological membranes in general and the properties of the lipid phase transition in particular. The lowering of the membrane melting point results in a change of the free energy of the lipid membrane, which is proportional to the difference between body temperature and the melting temperature of the membrane. This temperature difference, which is on the order of 15 K, is to be compared with the shift in melting point temperature of ≈−0.6 K at a typical critical anesthetic dose. Anesthetic effect can be reversed in a quantitatively predictable manner by any mechanism that raises the transition temperature and restores the free energy difference to its original value. Such mechanisms include hydrostatic pressure, a decrease of pH, an increase of calcium concentration, or the lowering of the body temperature. (The hydrostatic pressure necessary to reverse anesthesia is on the order of 24 bars, the pH change on the order of 0.4 pH units, and the hypothermic reversal of anesthesia is ∼0.6 K.) While these effects are well-documented, they have not previously been placed in common framework. Although we do not question the importance of a better understanding of the microscopic mechanisms underlying general anesthesia, these results support the view that the thermodynamics of the lipid liquid-gel transition is important for understanding the macroscopic effects of general anesthetic action. Finally, we note that a variety of biological phenomena, including fusion and membrane permeability, may reasonably be assumed to have a similar connection to this phase transition and that such assumptions can be tested using approaches similar to those presented here.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Benny Lautrup (Niels Bohr Institute) for critical discussions, and D. Pollakowski (Niels Bohr Institute) and Dr. M. Konrad (Göttingen) for permission to use their data on E. coli membranes before its detailed publication. We also thank Dr. D. Kharakoz for making his 2001 article available to us.

References

- 1.Meyer, H. 1899. On the theory of alcohol narcosis: first communication. Which property of anesthetics determines its narcotic effect? Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 425:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overton, C. E. 1901. Studies of Narcosis, Chapman and Hall, 1991. R. Lipnick, editor. Verlag Gustav Fischer, Jena, Germany.

- 3.Langerman, L., M. Bansinath, and G. J. Grant. 1994. The partition coefficient as a predictor of local anesthetic potency for spinal anesthesia: evaluation of five local anesthetics in a mouse model. Anesth. Analg. 79:490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreienbühl, G. 2002. Charles Ernest Overton: studies of narcosis (1901). An almost forgotten pioneer of the theory of narcosis. In Anästhesie in Zürich: 100 Jahre Entwicklung 1901–2001. T. Pasch, E. R. Schmid, and A. Zollinger, editors. Institute of Anesthesiology, Universitäts-Spital Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland.

- 5.Urban, B. W. 2002. The Meyer-Overton rule: what has remained? In Anästhesie in Zürich: 100 Jahre Entwicklung 1901–2001. T. Pasch, E. R. Schmid, and A. Zollinger, editors. Institute of Anesthesiology, Universitäts-Spital Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland.

- 6.Kinnunen, P. K. J., and J. A. Virtanen. 1986. A qualitative, molecular model of the nerve pulse. Conductive properties of unsaturated lyotropic liquid crystals. In Modern Bioelectrochemistry. F. Gutmann and H. Keyzer, editors. Plenum Press, New York.

- 7.Kharakoz, D. P. 2001. Phase-transition-driven synaptic exocytosis: a hypothesis and its physiological and evolutionary implications. Biosci. Rep. 210:801–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peoples, R. W., C. Li, and F. W. Weight. 1996. Lipid versus protein theories of alcohol action in the nervous system. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 36:185–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franks, N. P., and W. R. Lieb. 1994. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anesthesia. Nature. 367:607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franks, N. P., A. Jenkins, E. Conti, W. R. Lieb, and P. Brick. 1998. Structural basis for the inhibition of firefly luciferase by a general anesthetic. Biophys. J. 75:2205–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firestone, L. L., A. S. Janoff, and K. Miller. 1987. Lipid-dependent differential effects of stereoisomers of anesthetic alcohols. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 898:90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth, S. H. 1979. Physical mechanisms of anesthesia. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 19:159–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firestone, L. L., J. C. Miller, and K. W. Miller. 1986. Tables of physical and pharmacological properties of anesthetics. In Molecular and Cellular Mechanism of Anesthetics. S. H. Roth and K. W. Miller, editors. Plenum Press, New York.

- 14.Cantor, R. S. 1997. Lateral pressures in cell membranes: a mechanism for modulation of protein function. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:1723–1725. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantor, R. S. 1997. The lateral pressure profile in membranes: a physical mechanism of general anesthesia. Biochemistry. 36:2339–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantor, R. S. 2001. Breaking the Meyer-Overton rule: predicting effects of varying stiffness and interfacial activity on the intrinsic potency of anesthetics. Biophys. J. 80:2284–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, A. G. 1977. Local anesthesia: the interaction between phospholipids and chlorpromazine, propranolol, and practolol. Mol. Pharmacol. 13:474–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reference deleted in proof.

- 19.Ebel, H., P. Grabitz, and T. Heimburg. 2001. Enthalpy and volume changes in lipid membranes. I. The proportionality of heat and volume changes in the lipid melting transition and its implication for the elastic constants. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105:7353–7360. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollakowski, D. 2004. Thermodynamic and structural investigations on artificial and biological membranes. Fundamental characteristics and the influence of small molecules. Master's thesis, University of Göttingen.

- 21.Lee, A. G. 1977. Lipid phase transitions and phase diagrams. II. Mixtures involving lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 472:285–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain, M. K., and J. L. V. Wray. 1978. Partition coefficients of alkanols in lipid bilayer/water. Biochem. Pharmacol. 275:1294–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie, J. M., and R. D. Keynes. 1985. The production and absorption of heat associated with electrical activity in nerve and electric organ. Q. Rev. Biophys. 392:451–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaminoh, Y., N. Kitagawa, S. Nishimura, H. Kamaya, and I. Ueda. 1991. Two-state model for nerve excitation and local anesthetic action. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 625:315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaminoh, Y., S. Nishimura, H. Kamaya, and I. Ueda. 1992. Alcohol interaction with high entropy states of macromolecules: critical temperature hypothesis for anesthesia cutoff. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1106:335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heimburg, T., and A. D. Jackson. 2005. On soliton propagation in biomembranes and nerves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:9790–9795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lautrup, B., A. D. Jackson, and T. Heimburg. 2006. The stability of solitons in biomembranes and nerves. arXiv:physics/0510106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Papahadjopoulos, D., K. Jacobson, S. Nir, and T. Isac. 1973. Phase transitions in phospholipid vesicles. Fluorescence polarization and permeability measurements concerning the effect of temperature and cholesterol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 311:330–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boheim, G., W. Hanke, and H. Eibl. 1980. Lipid phase transition in planar bilayer membrane and its effect on carrier- and pore-mediated ion transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 77:3403–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruzeiro-Hansson, L., and O. G. Mouritsen. 1988. Passive ion permeability of lipid membranes modeled via lipid-domain interfacial area. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 944:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silbey, R. J., and R. A. Alberty. 2001. Physical Chemistry, 3rd Ed. J. Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 32.Cantor, R. S. 1999. Solute modulation of conformational equilibria in intrinsic membrane proteins: apparent “cooperativity” without binding. Biophys. J. 77:2643–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halsey, M. J., and B. Wardley-Smith. 1975. Pressure reversal of narcosis produced by anaesthetics, narcotics and tranquilizers. Nature. 257:811–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson, F. H., and E. A. Flagler. 1950. Hydrostatic pressure reversal of narcosis in tadpoles. Science. 112:91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trudell, J. R., D. G. Payan, J. H. Chin, and E. N. Cohen. 1975. The antagonistic effect of an inhalation anesthetic and high pressure on the phase diagram PF mixed dipalmitoyl-dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine bilayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 72:210–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamaya, H., I. Ueda, P. S. Moore, and H. Eyring. 1979. Antagonism between high pressure and anesthetics in the thermal phase transition of dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 550:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galla, H.-J., and J. R. Trudell. 1980. Asymmetric antagonistic effects of an inhalation anesthetic and high pressure on the phase transition temperature of dipalmitoyl phosphatidic acid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 599:336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heimburg, T. 1998. Mechanical aspects of membrane thermodynamics. Estimation of the mechanical properties of lipid membranes close to the chain melting transition from calorimetry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1415:147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss, G. W., W. R. Lieb, and N. P. Franks. 1991. Anesthetic inhibition of firefly luciferase, a protein model for general anesthesia, does not exhibit pressure reversal. Biophys. J. 60:1309–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendig, J. J., T. M. Schneider, and E. N. Cohen. 1978. Pressure, temperature and repetitive impulse generation and synaptic transmission. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir. Envir. Exercise Physiol. 45:742–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Träuble, H., and H. Eibl. 1974. Electrostatic effects on lipid phase transitions: membrane structure and ionic environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 71:214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Träuble, H., M. Teubner, and H. Eibl. 1976. Electrostatic interactions at charged lipid membranes. I. Effects of pH and univalent cations on membrane structure. Biophys. Chem. 43:319–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Punnia-Moorthy, A. 1987. Evaluation of pH changes in inflammation of the subcutaneous air pouch lining in the rat, induced by carreenan, dextran and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Oral Pathol. 16:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spyropoulos, C. S. 1961. Initiation and abolition of electrical response of nerve fiber by thermal and chemical means. Am. J. Physiol. 200:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobatake, Y., I. Tasaki, and A. Watanabe. 1971. Phase transition in membrane with reference to nerve excitation. Adv. Biophys. 208:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abelho, F. J., M. A. Castro, A. M. Neves, N. M. Landeiro, and C. C. Santos. 2005. Hypothermia in a surgical intensive care unit. BMC Anesthesiol. DOI:10.1186/1471-2253-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Katz, Y., and I. Aharon. 1997. A thermochemical analysis of inhalation anesthetics. J. Therm. Anal. 50:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 48.van de Vossenberg, J. L. C. M., A. J. M. Driessen, M. S. da Costa, and W. N. Konings. 1999. Homeostasis of the membrane proton permeability in Bacillus subtilis grown at different temperatures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1419:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]