Abstract

Force mode microscopy can be used to examine the effect of mechanical manipulation on the noncovalent interactions that stabilize proteins and their complexes. Here we describe the effect of complexation by the high affinity protein ligand E9 on the mechanical resistance of the simple four-helical protein, Im9. When concatenated into a construct of alternating I27 domains, Im9 unfolded below the thermal noise limit of the instrument (∼20 pN). Complexation of E9 had little effect on the mechanical resistance of Im9 (unfolding force ∼30 pN) despite the high avidity of this complex (Kd ∼10 fM).

Force is ubiquitous throughout biology and many proteins resist or respond to mechanical deformation at the nanometer scale (1). While the determinants of protein mechanical strength have been examined in detail, the effect of binding small nonproteinaceous ligands on mechanical strength has been investigated in only a few cases (2–5). In addition to small ligands, many proteins that have force-resistant or force-sensitive functions form complexes with one or many proteins, which may modulate their force response and therefore their function in vivo.

Here the effect of protein:protein complexation on protein mechanical stability is investigated using the high affinity interaction between the nuclease domain of the colicin E9 and its cognate immunity protein Im9 (Fig. 1). The E9:Im9 interaction, which involves burial of 1575 Å2 of protein surface (6) (see Supplementary Material Fig. S1), is one of the strongest known, with a dissociation constant of ∼10 fM and a binding free energy of ∼−80 kJ mol−1, depending on solvent conditions (7). The strength of this interaction, which is similar to that of biotin:streptavidin (8) and ∼106 times stronger than that of dihydrofolate reductase and methotrexate (9), makes this system ideal to monitor the effect of binding on mechanical strength. However, the mechanism by which this strong interaction is broken in vivo is unknown (a prerequisite for E9 to enter the target cell and carry out its bacteriocidal activity).

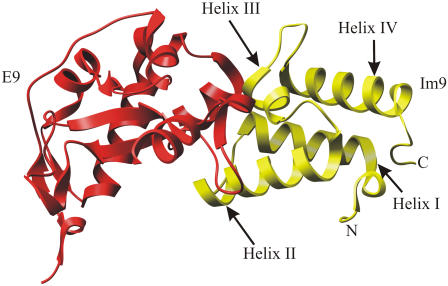

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the Im9:E9 complex (6).

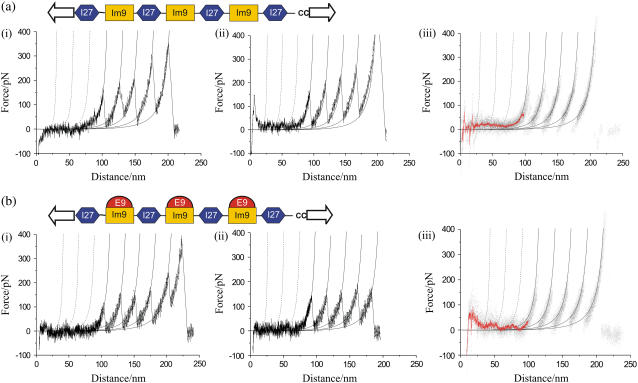

To assess the effect of complexation on the mechanical resistance of Im9, it was first necessary to characterize the mechanical properties of Im9 alone. To facilitate analysis, a heteropolymer comprising three Im9 domains alternating with four I27 domains from titin (herein denoted ((I27)4(Im9)3, Fig. 2 a, top) was constructed (see Supplementary Material), allowing the well-characterized I27 to act as a mechanical fingerprint. Mechanical unfolding data for (I27)4(Im9)3 at a retraction speed of 700 nm s−1 are shown in Fig. 2 a (i and ii). Traces were considered only when all 664 amino acids in the concatamers have been extended, as judged by the total extension length of 220 ± 2 nm (see Supplementary Material). Instead of the expected seven unfolding peaks, these force-extension profiles show a long extension at zero force, followed by four unfolding peaks and an unbinding event between the protein and tip or substrate. The mode unfolding force (186 ± 5 pN (n = 28)) and change in contour length (ΔLc, 26.0 ± 0.2 nm, n = 28; see Supplementary Material) of these peaks indicate that they report on the unfolding of I27 domains within the heteropolymer. These values correlate well with those observed in studies of an identical I27 domain within a concatamer of alternating protein L domains (I27)4(pL)3 (force = 180 ± 8 pN, ΔLc = 26.4 ± 0.5 nm at 700 nm s−1, n = 33, D. P. Sadler, S. E. Radford, D. A. Smith, and D. J. Brockwell, unpublished results). The observation of only four I27 unfolding events in the analyzed traces indicates that Im9 is mechanically labile since, in such a case, all three Im9 domains must have been fully extended before protein detachment from the cantilever tip.

FIGURE 2.

Mechanical unfolding of (I27)4(Im9)3 in (a) the absence and (b) the presence of E9. (i, ii) Representative unfolding profiles with a total contour length of ∼220 nm. (iii) Overlay of nine mechanical unfolding traces (dotted lines). A running average and worm-like chain fits to I27 unfolding events are shown as continuous red and black lines, respectively. Worm-like chain traces that describe the location of Im9 unfolding events calculated relative to the first I27 unfolding event are shown (dashed line).

In dynamic force experiments, the most probable force at which a protein unfolds increases as the extension rate increases. To increase the observed mechanical strength of Im9 above the thermal noise limit of the experiment, (I27)4(Im9)3 was unfolded at a retraction speed of 2100 nm s−1. However, no mechanical unfolding peak was observed that could be attributed to the unfolding of Im9 domains. This thermodynamically and kinetically robust protein ( = 27.1 kJ mol−1,

= 27.1 kJ mol−1,  = 0.0124 s−1 at pH 7 and 10°C (10)) therefore either unfolds at a force <20 pN (the thermal noise of the experiment) when mechanically extended or is destabilized upon concatenation to such an extent that it is no longer folded. However, the far-UV CD spectrum for (I27)4(Im9)3 is consistent with that expected for a mixture of natively folded I27 and Im9 domains at a ratio of 4:3 (see Supplementary Material), ruling out the latter possibility. Im9 is thus mechanically labile, a result consistent with the observation that, in general, all α-helical proteins are mechanically weaker than their all β-sheet counterparts (see Table 1 in (11)). Interestingly, as previously observed for β-stranded proteins (12), the position of the points of extension relative to the topology of a protein appears to play a role in defining the mechanical strength of all α-helical proteins. Thus, while spectrin domains have distal N- and C-termini and unfold at forces 20–70 pN (13–15), Im9 has proximal termini and unfolds at a much lower force.

= 0.0124 s−1 at pH 7 and 10°C (10)) therefore either unfolds at a force <20 pN (the thermal noise of the experiment) when mechanically extended or is destabilized upon concatenation to such an extent that it is no longer folded. However, the far-UV CD spectrum for (I27)4(Im9)3 is consistent with that expected for a mixture of natively folded I27 and Im9 domains at a ratio of 4:3 (see Supplementary Material), ruling out the latter possibility. Im9 is thus mechanically labile, a result consistent with the observation that, in general, all α-helical proteins are mechanically weaker than their all β-sheet counterparts (see Table 1 in (11)). Interestingly, as previously observed for β-stranded proteins (12), the position of the points of extension relative to the topology of a protein appears to play a role in defining the mechanical strength of all α-helical proteins. Thus, while spectrin domains have distal N- and C-termini and unfold at forces 20–70 pN (13–15), Im9 has proximal termini and unfolds at a much lower force.

Next, the effect of complexation on the mechanical properties of Im9 were assessed by mechanically unfolding a preformed complex of (I27)4(Im9)3:(E9)3. Before mechanical unfolding experiments were undertaken, in vivo and in vitro toxicity assays and size-exclusion chromatography were used to demonstrate that E9 binds tightly to Im9 within (I27)4(Im9)3 and does not dissociate on the timescale of the mechanical unfolding experiments (see Supplementary Material). Sample force-extension profiles of the extension of (I27)4(Im9)3:(E9)3 at 700 nm s−1 are shown in Fig. 2 b (i and ii). Again traces only involving extension of the entire polypeptide chain (Lc = 221 ± 1 nm) were considered. At this contour length, the polypeptide chain is fully extended and, as the Im9:E9 interface is large (1575 Å2), involving at least 16 residues spread across helices I–III (6) (see Supplementary Material Fig. S1), E9 must have dissociated from the fully extended Im9 polypeptide chain. Mechanical unfolding of (I27)4(Im9)3:(E9)3 shows four unfolding events at high force (185 ± 6 pN) spaced at a distance characteristic of the unfolding of I27 domains (26.0 ± 0.28 nm, n = 28). However, by contrast with (I27)4(Im9)3 alone, the force profiles displayed small, but significant, events just above the thermal noise of the experiment which could be attributed to the unfolding of Im9. To obviate nonspecific interactions as the origin of these unfolding events, nine force-extension profiles were overlaid and a running average calculated (red line, Fig. 2 b (iii)). The improved signal/noise reveals the presence of two small unfolding events (at a force of ∼30 pN), which are not observed when the same process is performed for data accumulated in the absence of E9 (red line, Fig. 2 a (iii)). Furthermore, these unfolding events show reasonable agreement with changes in contour lengths expected for an Im9 unfolding event (Fig. 2 b (iii)). Binding of E9 to Im9 within (I27)4(Im9)3 thus increases the mechanical resistance of Im9 to a level whereby the unfolding of this mechanically weak domain can just be observed. However, the degree of stabilization is remarkably small, given the large free energy of complex formation (E9 binds to the Im9 with a free energy of ∼−80 kJ mol−1 (7)).

The mechanical lability of such a stable protein:protein complex is remarkable. By contrast with chemical denaturants, which act globally on the polypeptide chain, force acts locally and is applied at defined points onto the protein. Importantly these points are distal to the Im9:E9 binding interface (which comprises residues in helices I–III of Im9; see Supplementary Material Fig. S1), possibly rationalizing why the binding of E9 only marginally stabilizes Im9 to mechanical deformation. A similar conclusion has recently been reported for the effect of ligand binding on the mechanical resistance of DHFR and calmodulin (2,4). While the binding of high affinity ligands significantly increased the thermodynamic stability of calmodulin (4) and mouse dihydrofolate reductase (2), their mechanical strength is also relatively insensitive to complexation. However, by contrast with these observations, addition of ligands to a different DHFR variant (3) or addition of Ca2+ to a different calmodulin construct (5) resulted in a significant increase in mechanical strength, highlighting the sensitivity of the mechanical response to the precise protein sequence or construct analyzed.

Here we have shown that the simple four-helical protein Im9 is mechanically weak and unfolds at a force <20 pN. Surprisingly, mechanically unfolding Im9 in the presence of E9 only marginally stabilized Im9 against mechanical extension despite the high avidity of this complex. This highlights the ability of force to dissociate even the strongest protein:protein interaction when applied in a suitable geometry relative to the protein topology. This may suggest a method by which long-lasting complexes are rapidly dissociated in vivo by the application of a moderate force. Such a mechanism has been postulated for the remodeling of the Mu recombination complex by the ClpX unfoldase of E. coli (16). Interestingly, recent work on a similar endonuclease colicin:immunity protein complex (E2:Im2) suggests that release of Im2 requires a functional Tol complex. This complex acts as an energy transducer and may provide a link between the proton motive force of the inner membrane and complex dissociation at the outer membrane (17).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kirstine Anderson, Anthony Blake, and David Sadler for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the University of Leeds. D.J.B. is an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council-funded White Rose Doctoral Training Centre lecturer.

References

- 1.Bustamante, C., Y. R. Chemla, N. R. Forde, and D. Izhaky. 2004. Mechanical processes in biochemistry. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:705–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Junker, J., K. Hell, M. Schlierf, W. Neupert, and M. Reif. 2005. Influence of substrate binding on the mechanical stability of mouse dihydrofolate reductase. Biophys. J. 105:L46–L48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainavarapu, S. R., L. Li, C. L. Badilla, and J. M. Fernandez. 2005. Ligand binding modulates the mechanical stability of dihydrofolate reductase. Biophys. J. 89:3337–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrion-Vazquez, M., A. F. Oberhauser, T. E. Fisher, P. E. Marszalek, H. Li, and J. M. Fernandez. 2000. Mechanical design of proteins studied by single-molecule force spectroscopy and protein engineering. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 74:63–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hertadi, R., and A. Ikai. 2002. Unfolding mechanics of holo- and apocalmodulin studied by the atomic force microscope. Protein Sci. 11:1532–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhlmann, U. C., A. J. Pommer, G. R. Moore, R. James, and C. Kleanthous. 2000. Specificity in protein-protein interactions: the structural basis for dual recognition in endonuclease colicin-immunity protein complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 301:1163–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallis, R., G. R. Moore, R. James, and C. Kleanthous. 1995. Protein-protein interactions in colicin E9 DNAse-immunity protein complexes. 1. Diffusion-controlled association and femtomolar binding for the cognate complex. Biochemistry. 34:13743–13750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamandis, E. P., and T. K. Christopoulos. 1991. The biotin (strept)avidin system—principles and applications in biotechnology. Clin. Chem. 37:625–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appleman, J. R., N. Prendergast, T. J. Delcamp, J. H. Freisheim, and R. L. Blakley. 1988. Kinetics of the formation and isomerization of methotrexate complexes of recombinant human dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 263:10304–10313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson, N., A. P. Capaldi, R. James, C. Kleanthous, and S. E. Radford. 1999. Rapid folding with and without populated intermediates in the homologous four-helix proteins Im7 and Im9. J. Mol. Biol. 286:1597–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brockwell, D. J., G. S. Beddard, E. Paci, D. K. West, P. D. Olmsted, D. A. Smith, and S. E. Radford. 2005. Mechanically unfolding the small, topologically simple protein L. Biophys. J. 89:506–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockwell, D. J., E. Paci, R. C. Zinober, G. S. Beddard, P. D. Olmsted, D. A. Smith, R. N. Perham, and S. E. Radford. 2003. Pulling geometry defines the mechanical resistance of a beta-sheet protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:731–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altmann, S. M., R. G. Grunberg, P. F. Lenne, J. Ylanne, A. Raae, K. Herbert, M. Saraste, M. Nilges, and J. K. Horber. 2002. Pathways and intermediates in forced unfolding of spectrin repeats. Structure. 10:1085–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhasin, N., R. Law, G. Liao, D. Safer, J. Ellmer, B. M. Discher, H. L. Sweeney, and D. E. Discher. 2005. Molecular extensibility of mini-dystrophins and a dystrophin rod construct. J. Mol. Biol. 352:795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenne, P. F., A. J. Raae, S. M. Altmann, M. Saraste, and J. K. Horber. 2000. States and transitions during forced unfolding of a single spectrin repeat. FEBS Lett. 476:124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burton, B., and T. Baker. 2006. Remodeling protein complexes: insights from the AAA + unfoldase ClpX and Mu transposase. Protein Sci. 14:1945–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duché, D., A. Frenkian, V. Prima, and R. Lloubès. 2006. Release of immunity protein requires functional endonuclease colicin import machinery. J. Bacteriol. 188:8593–8600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.