Abstract

Preoperative diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma is difficult, and the treatment for it remains controversial. The aim of this study is to review our experience in the treatment of hepatic angiomyolipoma and to propose a treatment strategy for this disease. We retrospectively collected the clinical, imaging, and pathological features of patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma. Immunohistochemical studies with antibodies for HMB-45, actin, S-100, cytokeratin, vimentin, and c-kit were performed. Treatment experience and long-term follow-up results are summarized. During a period of 9 years, 10 patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma were treated at our hospital. There was marked female predominance (nine patients). Nine patients received surgical resection without complications. One patient received nonoperative management with biopsy and follow-up. One patient died 11 months after surgery because of recurrent disease. We propose all symptomatic patients should receive surgical resection for hepatic angiomyolipoma. Conservative management with close follow-up is suggested in patients with asymptomatic tumors and meet the following criteria: (1) tumor size smaller than 5 cm, (2) angiomyolipoma proved through fine needle aspiration biopsy, (3) patients with good compliance, and (4) not a hepatitis virus carrier.

Keywords: Angiomyolipoma, Hepatic angiomyolipoma, Liver tumor

Introduction

Hepatic angiomyolipoma (AML) is a rare mesenchymal tumor of the liver composed of smooth muscle cells, adipose tissue, and proliferating blood vessels. Since its first description by Ishak in 1976, approximately 200 cases have been reported in the English literature.1 This type of tumor is usually seen in kidneys associated with tuberous sclerosis.2 Definite pathologic diagnosis is made by identification of the three different components and HMB-45 positive staining.3

In the past, this tumor has been considered an entirely benign and slow-growing lesion without the possibility of malignant transformation. Therefore, several authors have suggested that this disease can be managed with conservative treatment.4–7 However, since 2000, several reports have revealed that this kind of tumor can be malignant with evidence of recurrence.8–10 Although the combination of ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, and angiography increases the accuracy in diagnosis of hepatic AML, the correct preoperative diagnostic rate of imaging studies has been reported to be less than 50%.6,10–14 Even the postoperative pathologic diagnosis has been easily mistaken as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).14,15 Many patients have been treated with surgical resection of the tumor. Therefore, the proper treatment of hepatic AML has remained controversial.

The purpose of this study is to retrospectively review the clinical, imaging, and pathological features of patients with hepatic AML treated at our hospital and to summarize our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. We also review the literature to highlight the important questions concerning hepatic AML: (1) Is hepatic AML a pure benign tumor? (2) What is the natural course of this tumor? Does the tumor size enlarge frequently during observation? (3) What difficulties exist in preoperative diagnosis with imaging studies and fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB)? (4) Is it proper for a hepatitis-carrier patient with hepatic AML to be treated with conservative management? (5) What are the criteria for patients with hepatic AML to be treated with surgical resection or conservative management?

Materials and Methods

The clinical, imaging, and pathological features of 10 patients with hepatic AML treated at the authors’ institute were retrospectively reviewed. The follow-up information was obtained in each case. All tumor tissue was paraffin-embedded for routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Immunohistochemical assays were performed using a three-step indirect peroxidase complex technique with the following antibodies: HMB-45 (DAKO, dilution 1:40), actin (DAKO, dilution 1:50), S-100 (DAKO, dilution 1:800), cytokeratin (Biogenix, dilution 1:80), vimentin (DAKO, dilution 1:50), and c-kit (MBL, dilution 1:200).

Results

Patients and Clinical Data

Ten patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma were diagnosed at National Taiwan University Hospital from July 1995 to June 2004. There was marked female predominance (9/10). The median age was 44 years old with a range from 34 to 64 years. Most patients (60%) presented no symptoms and were detected incidentally by health check-ups or during medical exams for other diseases. Four of 10 patients had symptoms caused by the space-occupying effect of the tumors such as abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and palpable mass, or other nonspecific symptoms such as fever, general malaise, or body weight loss (Tables 1 and 2). None of them had a history of renal AML or tuberous sclerosis. Two patients were hepatitis B-virus (HBV) carriers. The plasma levels of α-FP and CEA were within normal limits in all patients.

Table 1.

Clinical Presentation of Hepatic Angiomyolipoma

| Clinical Feature | No. of Patients |

|---|---|

| Age | 34–64 years (median 44 years) |

| Gender (female: male) | 9:1 |

| Symptoms | |

| No symptom | 6 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 |

| Abdominal fullness | 2 |

| Palpable mass | 1 |

| Body weight loss | 2 |

| Malaise | 1 |

| Fever | 2 |

| Tumor location | |

| Right lobe | 5 |

| Left lobe | 4 |

| Caudate | 1 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| <5 | 3 |

| 5–10 | 1 |

| >10 | 6 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | |

| Angiomyolipoma | 4(40%) |

| Based on radiological images | 2 |

| Based on tumor biopsy | 2 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 3(30%) |

| Angiosarcoma | 1(10%) |

| Hemangioma | 1(10%) |

| Metastasis | 1(10%) |

| Associated liver disease | |

| HBV carrier | 2 |

Table 2.

Clinical Profile of Patients with Hepatic Angiomyolipoma

| Case | Sex/Age | Tumor Size (cm)/lobe | Symtoms/Signs | Incidental Finding | Treatment | Outcome/F/U Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F/34 | 18/R | Nil | H/C | Atypical hepatectomy | Well/39 mon |

| 2 | F/34 | 10/R | Epigastralgia | Right lobectomy | Well/59 mon | |

| 3 | F/37 | 13/L | Palpable mass, abdominal fullness, BW loss, fever | Extended left lobectomy | Dead/14 mon recurrent, liver and lung mets | |

| 4 | F/40 | 20/R | Epigastralgia | Right lobectomy | Well/109 mon | |

| 5 | F/42 | 7/R | Nil | H/C | FNAB and F/U | Lost F/U/6mon |

| 6 | F/46 | 11/L | Abdominal fullness, malaise, BW loss, fever | Left lateral segmentectomy | Well/40 mon | |

| 7 | F/49 | 15/R | Nil | Exam of appendicitis | S56 segmentectomy | Well/37 mon |

| 8 | F/51 | 3/C | Nil | H/C | Caudate lobectomy | Well/40 mon |

| 9 | F/53 | 2.5/L | Nil | F/U echo due to colon cancer s/p | Left lateral segmentectomy | Well/33 mon |

| 10 | M/64 | 4/L | Nil | H/C | Left lobectomy | Well/32mon |

H/C = health check-up, BW = body weight, F/U = follow-up, FNAB = fine needle aspiration biopsy, mon = month, mets = metastasis, s/p = postoperation

Imaging Studies

Based on the combined imaging studies of abdominal ultrasonography, CT, MR imaging, and angiography, the diagnostic accuracy of hepatic AML in this series was only 20% (Table 1). Other preoperative imaging impressions included hepatocellular carcinoma, angiosarcoma, hemangioma, and metastatic lesions.

Two other cases were diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). The accurate preoperative diagnostic rate was 40% (4/10) after imaging studies and FNAB (Table 1).

Pathologic Study

All 10 patients had a single tumor. Five tumors were in the right lobe of the liver and four were in the left lobe. One tumor was located in the caudate lobe. Most tumor sizes were larger than 5 cm (70%). The median tumor size was 10.5 cm, ranging from 2.5 cm to 20 cm (Tables 1 and 2).

Gross pathology identified all tumors as a well-circumscribed, nonencapsulated tumor masses consisting of soft to elastic tissue. The cut surface in tumors varied from yellow to dark brown.

Histopathologic studies of these 10 tumors showed a picture of hepatic angiomyolipoma composed of myoid and vascular components with a variant content of fatty tissue. Hematopoiesis was noted in two cases. Immunohistochemical studies were performed in all patients except one (case 5). Most tumors were found positive for HMB-45 (10/10), SMA (4/9), S-100 (7/9), Vimentin (6/9), but negative for cytokeratin (0/9). Only three tumors were found positive for c-kit (Table 3).

Table 3.

Immunohistochemical Study

| Case | HMB-45 | Actin | S-100 | Cytokeratin | Vimentin | c-kit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ++ | − | ++ | − | − | + |

| 2 | ++ | ++ | + | − | + | + |

| 3 | ++ | − | ++ | − | + | − |

| 4 | ++ | ++ | − | − | + | − |

| 5 | ++ | |||||

| 6 | ++ | + | ++ | − | + | − |

| 7 | ++ | − | ++ | − | + | − |

| 8 | ++ | − | − | − | + | − |

| 9 | ++ | − | ++ | − | − | − |

| 10 | ++ | + | + | − | + | + |

++: strongly staining, >30% positivity; +: weakly staining, 10∼30% positivity; − no staining, or <10% positivity

Treatment and Follow-up

One patient (case 5) was confirmed with AML through fine needle aspiration biopsy. Nonoperative management with close follow-up was performed. However, this patient was lost after 6 months of follow-up. The other nine patients underwent hepatectomy with tumor resection. These nine patients, except for one patient (case 3), had no postoperative complications or disease recurrence, and were regularly followed up at our outpatient department, follow-up ranging from 32 to 109 months (Table 2). The very unusual patient (case 3) was a 37-year-old woman with a 13 × 9 × 9 cm, large tumor at the left lobe of the liver, receiving extended left lobectomy (Fig. 1a,b). Pathology revealed a picture of hepatic AML (Fig. 2a,b).

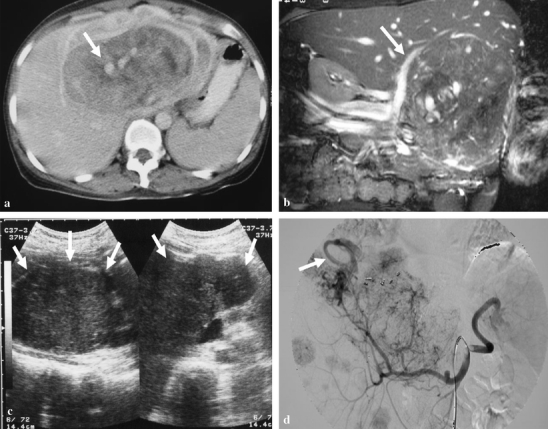

Figure 1.

A 37-year-old woman (case 3) presented with fever and palpable abdominal mass. (a) The axial view of contrast-enhanced CT scans on portal venous phase shows a huge hepatic tumor at the left hepatic lobe with heterogeneous enhancement. Notice the engorged vessels within the tumor are vividly identified (arrow). (b) The MR coronal Tru FISP, fast imaging with steady-state precession. (TR/TE/FA = 4.3/2.1/72°) shows engorged vessels in the tumor. The right portal vein (arrow) is displaced by the tumor. (c) After 6 months of extended left lobectomy, the abdominal ultrasonography reveals a huge recurrent tumor (arrows) in the previous location of left hepatic lobe, and numerous smaller tumors in the right lobe. (d) Celiac angiography also demonstrates the recurrent huge tumor and other multiple smaller ones in the right lobe of liver. Note the early drainage vein (arrow).

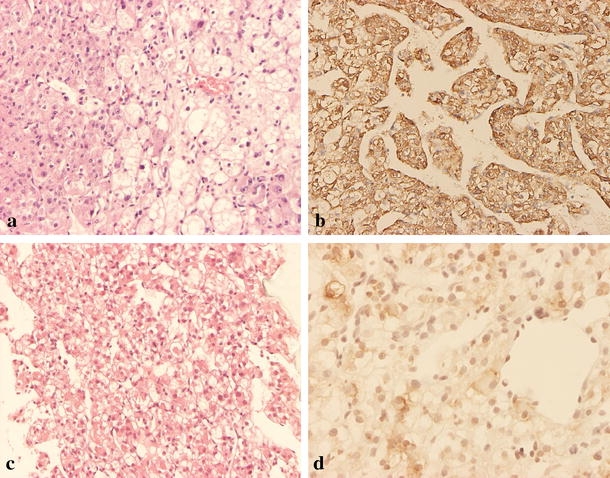

Figure 2.

Microscopic appearance of the hepatic angiomyolipoma in case 3. (a) The primary tumor is composed of polygonal to spindle cells arranged in solid sheets or trabecular pattern with endothelial lining. Some of the tumor cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm, and some have large fat vacuoles. Some of the nuclei are bizarre, and some have large eosinophilic nucleoli (H&E stain, original magnification ×100). (b) The tumor cells are strongly immunoreactive for HMB-45 (original magnification ×100). Recurrent tumor was noted 6 months later, and the patient received fine needle aspiration biopsy. (c) Microscopically, it shows tumor cells with clear to ample eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in trabecular pattern (H&E stain, original magnification ×40). (d) Immunohistochemical staining shows the tumor cells are also positive for HMB-45 (original magnification ×200).

Unfortunately, 6 months later, ultrasonography showed recurrent hepatic lesions at the right lobe of the liver (Fig. 1c). MRI also confirmed a large tumor in the caudate lobe and numerous smaller nodules in the right lobe of the liver. Angiography also revealed multiple tumor stains (Fig. 1d). Fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed. The biopsy specimen was immunoreactive to HMB-45 antibody (Fig. 2c,d). The clinical and histologic picture demonstrated recurrent malignant hepatic angiomyolipoma. At the 11th postoperative month, chest CT scans revealed multiple metastatic nodules. Three months later, the woman died due to hepatic failure and renal failure.

Discussion

In the past, hepatic AML has been considered as a “benign” mesenchymal tumor. However, in 2000, Dalle reported the first case of malignant hepatic AML with vascular invasion and recurrence with multiple liver metastases and suspected portal vein thrombosis 5 months after primary tumor resection.8 Another two cases have been reported with hepatic recurrence after operation. One case was a 16-year-old girl with hepatic AML, receiving left lobectomy, with late recurrence noted 6 years after operation.9 The other one was in the Flemming’s report. Recurrent hepatic tumors were noted 3 years after operation.10 Flemming also suggested that a proliferation index exceeding 3% and multicentric growth indicate a propensity for recurrence.

In this study, we reported a 37-year-old woman with left hepatic AML. A recurrent hepatic mass was noted 6 months after tumor resection, and multiple lung metastases were noted later. The patient died 14 months after diagnosis. To our knowledge, this case is the fourth reported case of recurrence in the literature, and the tumor in this case behaved as the most malignant one.8–10 Therefore, hepatic AML should not be considered as an entirely benign tumor; at least, it has malignant transformation potential. Accordingly, conservative treatment should be performed carefully, especially for patients with poor compliance, who are unable to undergo a strict follow-up regimen.

There were few reports concerning the growth velocity of hepatic AML in long-term follow-up. In one retrospective study of 26 patients, there were six patients who were followed up for more than 1 year and finally decided to receive operation because of the enlargement of the lesions. In that study, the tumor size of one patient increased from 4 to 10 cm during the 5-year follow-up. Another patient had a tumor increasing from 1.5 to 5 cm in 13 years follow-up.13 In another case report of a 38-year-old patient, the tumor size enlarged from 8 to 14.4 cm over a 3-year follow-up period.16 Irie also reported that a 40-year-old woman had hepatic AML with tumor size increasing in size from 4 cm to 7 cm during a 14-month follow-up period.16

Although hepatic AML seems slow-growing, the probability of tumor enlargement and hence an induced mass-compression effect is not uncommon in the long-term follow-up period. In the present series, the median age of patients was 44 years old, and 70% of patients were below 50 years. If all of these patients had received nonoperative management, the mass effect of tumor enlargement might have been presented during a long-term follow-up period, especially in younger patient groups with longer remaining years of life. Moreover, the difficulties and complications of operation at later years would increase when the tumor enlarges, especially for those patients with an original larger tumor (>5 cm).

Similar to the patients presented in this series, most patients with hepatic AML are not symptomatic.12–14 Usually, these patients are diagnosed during health check-ups. Most symptoms are mass-compression effects including upper abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and palpable mass. There are also some vague symptoms such as body weight loss, general malaise, and fever. In one review article with a collection of 52 patients, the incidence of symptoms or signs dramatically increased when tumor size was larger than 5 cm.11 Twenty-one percent (4/19) of patients with a tumor smaller than 5 cm present symptoms/signs; however, the incidence increases to 64% (7/11) when tumor size is between 5 and 10 cm. The incidence increases to 89% when tumor size is larger than 10 cm. In our series, 40% (4/10) of patients were symptomatic, and all four of these patients had a tumor larger than 10 cm. Accordingly, we suggested that patients with tumor larger than 5 cm should receive tumor resection, because most patients in this group were predisposed toward being symptomatic.

The typical findings in imaging studies of hepatic AML are as follows: (1) heterogeneously hyperechoic mass in US, (2) heterogeneously low density with low attenuation value (less than −20 HU) in plain CT, (3) high intensity on T1 and T2 weighted MRI, and (4) hypervascularity and tumor stain on angiography.12 Although a combination of US, CT, MRI, and angiography is able to increase the accuracy in preoperative diagnosis, hepatic AML usually shows various patterns in imaging studies. The differences in imaging studies occur because the relative proportions of vessels, muscles, and fatty tissue vary widely from one tumor to another. Consequently, hepatic AML is sometimes difficult to diagnose based on imaging studies.17 Therefore, fine needle aspiration biopsy has been reported to be useful in the preoperative diagnosis of this tumor.4,5,17,18

However, more attention should be paid to the tumor’s various morphologic appearances when minute samples are interpreted. With the combined tools of imaging studies and FNAB, the preoperative diagnostic accuracy has been smaller than 32% (ranging from 0 to 32%) in larger series.6,10–15 In a collaborative study reported by Tsui, including 30 cases from nine international hepatology centers, 50% were primarily misdiagnosed as carcinoma or sarcoma, either by imaging studies or by needle biopsy.15 In Flemming’s series, only one preoperative case was diagnosed correctly.10 In the present series, only four preoperative cases (40%) were correctly diagnosed by combined imaging studies and FNAB.

Definite pathologic diagnosis of this tumor is usually made by identification of the three different components of smooth muscle cells, adipose tissue, and blood vessels. HMB-45 positive staining of myoid cells has been used as a pathologic characteristic of hepatic AML.3,19 Because of the rarity and pleomorphism of the histological features of hepatic AML, histologic diagnosis may be difficult, especially with needle biopsy. Many features in AML can mislead the unwary pathologist to a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: polygonal cells in trabecular arrangement, peliosis, nuclear pleomorphism, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, deficient reticulin framework, presence of glycogen, eosinophilic globules, and tumor necrosis.14 In Zhong’s series of 2000, none of the 14 cases were correctly diagnosed before operation. Furthermore, five cases were misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma or sarcoma by pathologists, even after operation. Therefore, we should be cautious when using FNAB as a diagnostic tool.

In an endemic area of hepatocellular carcinoma such as Taiwan,20 conservative management is risky because cases of fat-rich minute hepatocellular carcinoma will make the differential diagnosis more difficult. Furthermore, Chang reported one case with hepatic AML and concomitant hepatocellular carcinoma.21 In this series, two patients were carriers of hepatitis B virus with a high risk for hepatoma formation. Not only would these hepatitis-carrier patients bear more risk, but physicians would also bear more risk and psychological pressure during a long-term follow-up period if conservative management were adopted.

Because of the small patient number, we could not get definitely conclusive management suggestions solely from the results of this retrospective study. But a combination of our experience and a review of the literature, we suggest all symptomatic patients should receive surgical resection for hepatic angiomyolipoma. Conservative management with close follow-up is suggested in patients with asymptomatic tumors and meet the following criteria: (1) tumor size smaller than 5 cm, (2) angiomyolipoma proved through fine needle aspiration biopsy, (3) patients with good compliance, and (4) not a hepatitis-virus carrier.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kao-Lung Liu (Department of Radiology, National Taiwan University Hospital) for assistance with Fig. 1 and interpretation of radiologic pictures.

References

- 1.Ishak KG. Mesenchymal tumors of the liver. In: Okuda K, Peters RL, eds. Hepatocellular carcinoma. New York: John Wiley and Sons:, 1976 247–307.

- 2.Kitano Y, Honna T, Nihei K, et al. Renal angiomyolipoma in Japanese tuberous sclerosis patients. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:1784–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG, Shekar R, et al. Melanoma markers in angiomyolipoma of the liver and kidney: a comparative study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ma TK, Tse MK, Tsui WM, et al. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of angiomyolipoma of the liver using a cell block with immunohistochemical study. A case report. Acta Cytol 1994;38:257–60. [PubMed]

- 5.Cha I, Cartwright D, Guis M, et al. Angiomyolipoma of the liver in fine-needle aspiration biopsies: its distinction from hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 1999;87:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Yeh CN, Chen MF, Hung CF, et al. Angiomyolipoma of the liver. J Surg Oncol 2001;77:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Yamada N, Shinzawa H, Makino N, et al. Small angiomyolipoma of the liver diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy under ultrasound guidance. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1993;8:495–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Dalle I, Sciot R, de VR, et al. Malignant angiomyolipoma of the liver: a hitherto unreported variant. Histopathology 2000;36:443–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Croquet V, Pilette C, Aube C, et al. Late recurrence of a hepatic angiomyolipoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:579–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Flemming P, Lehmann U, Becker T, et al. Common and epithelioid variants of hepatic angiomyolipoma exhibit clonal growth and share a distinctive immunophenotype. Hepatology 2000;32:213–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Nonomura A, Mizukami Y, Kadoya M. Angiomyolipoma of the liver: a collective review. J Gastroenterol 1994;29:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Sajima S, Kinoshita H, Okuda K, et al. Angiomyolipoma of the liver—a case report and review of 48 cases reported in Japan. Kurume Med J 1999;46:127–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ren N, Qin LX, Tang ZY, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic angiomyolipoma in 26 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2003;9:1856–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Zhong DR, Ji XL. Hepatic angiomyolipoma—misdiagnosis as hepatocellular carcinoma: A report of 14 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2000;6:608–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Tsui WM, Colombari R, Portmann BC, et al. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases and delineation of unusual morphologic variants. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:34–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Irie H, Honda H, Kuroiwa T, et al. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: report of changing size and internal composition on follow-up examination in two cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1999;23:310–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Messiaen T, Lefebvre C, Van BB, et al. Hepatic angiomyo(myelo)lipoma: difficulties in radiological diagnosis and interest of fine needle aspiration biopsy. Liver 1996;16:338–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Blasco A, Vargas J, de AP, et al. Solitary angiomyolipoma of the liver. Report of a case with diagnosis by fine needle aspiration biopsy. Acta Cytol 1995;39:813–6. [PubMed]

- 19.Weeks DA, Malott RL, Arnesen M, et al. Hepatic angiomyolipoma with striated granules and positivity with melanoma-specific antibody (HMB-45): a report of two cases. Ultrastruct Pathol 1991;15:563–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hu RH, Lee PH, Chang YC, et al. Prognostic factors for hepatocellular carcinoma < or = 3 cm in diameter. Hepatogastroenterology 2003;50:2043–8. [PubMed]

- 21.Chang YC, Tsai HM, Chow NH. Hepatic angiomyolipoma with concomitant hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:253–5. [PubMed]