Introduction

An outbreak of an infectious animal disease that threatens the national herd is an emergency situation. Part of the strategy to contain and eventually eradicate the causal agent is targeted depopulation of the infected animals and those animals in close contact or proximity that potentially may be infected.

“When animals are killed for disease control purposes, methods used should result in immediate death or immediate loss of consciousness lasting until death; when loss of consciousness is not immediate, induction of unconsciousness should be non-aversive and should not cause anxiety, pain, distress or suffering in the animals” (1) (Table 1).

Table 1.

World Organization for Animal Health acceptable methods for killing animals for disease control purposes (1)

| Species | Age range | Procedure | Restraint necessary | Animal welfare concerns with inappropriate application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | All | Free bullet | No | Non-lethal wounding |

| All except neonates | Captive bolt — penetrating, followed by pithing or bleeding | Yes | Ineffective stunning | |

| Adults only | Captive bolt — non-penetrating, followed by bleeding | Yes | Ineffective stunning, regaining of consciousness before killing | |

| Calves only | Electrical, two stage application | Yes | Pain associated with cardiac arrest after ineffective stunning | |

| Calves only | Electrical, single application (method 1) | Yes | Ineffective stunning | |

| All | Injection with barbiturates and other drugs | Yes | Non-lethal dose, pain associated with injection site |

Under field conditions, fulfilling these requirements is challenging. The 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak in Britain required the culling of 6 million livestock (2), 4 million of which needed to be destroyed on-farm.

Firearms

In a mass depopulation scenario involving adult cattle in Canada, firearms are readily available. A bullet fired from a rifle of appropriate caliber used by a good marksman is capable of reliably killing adult cattle through the massive transfer of energy and the resulting damage to the brain (3). The free bullet first stuns and then kills the animal in very quick succession (4). Safety precautions may allow the use of free bullets in open areas. Whenever firearms are used in enclosed spaces or when the animals stand on hard surfaces, free bullets may exit the carcass with sufficient speed to ricochet from solid objects and pose a risk to personnel and other animals. Such a situation also exists whenever cattle have to be destroyed inside a vehicle (emergency response after a livestock truck rollover; a nonambulatory animal that must be stunned prior to being unloaded). Using an alternative to the free bullet may be preferable in such cases.

A penetrating captive bolt, with a sufficiently high bolt speed, in good state of repair, and used properly will stun an animal. Death may result as a consequence of the physical damage to the brain caused by penetration of the bolt, but death is not a guaranteed outcome. The immediate question is, What percentage of animals is killed by a captive bolt?

One benchmark is provided by audit reports — the best slaughter plants under the best conditions average 97% to 98% successful stuns (5). “Successful” does not mean that these stuns were irreversible or that the animal was killed. The animals were rendered insensible between stunning and death through exsanguination (stun-stick interval). In one study conducted in a controlled slaughterhouse environment, approximately 1.2% of bulls and cull cows returned to sensibility after captive bolt stunning, prior to being hoisted onto the rail (6). According to another study conducted in abattoirs in the UK, 6.6% of 1284 steers and heifers were stunned poorly; 1.7% of 628 cull cows were stunned poorly; but young bulls appeared to be particularly hard to stun correctly and 53.1% of 32 bulls in the study were stunned poorly (7).

In a disease control situation, the work environment is different from that of an abattoir. Animals may not be well restrained and lighting conditions may be inadequate, both situations making accurate aiming of the captive bolt gun more difficult. Operators may be increasingly fatigued due to the unusually high workload and the physical and psychological demands of emergency response-type work in a disease outbreak situation. Stunning equipment may not receive the same amount of maintenance and care in the field, as is expected in a slaughterhouse environment.

Therefore, it is to be expected that the percentage of successful stuns will be lower under field conditions than in a slaughterhouse and to ensure death, the animal needs to be bled out as soon as possible after the captive bolt shot. However, from a disease control standpoint, dissemination of body fluids in the open harbors the risk of dispersing a disease agent; thus, this may not be a viable option.

Shooting animals with what is essentially a stunning device in the hope that the stunning is irreversible and will lead to death amounts to a gamble and would run contrary to the OIE recommendations.

Given the large numbers of animals that may have to be destroyed, even a low percentage of ineffective kills that lead to animals returning to sensibility is unacceptable from an animal welfare standpoint and undesirable in the context of efficient disease control operations; moreover, the sight of severely wounded animals regaining sensibility, showing coordinated movement, and even attempting to get up would be distressing for onlookers and for personnel who have to restun and kill such animals.

Pithing is an alternative to exsanguination. The effectiveness of a pithing protocol compared with a stunning-only protocol for ensuring permanent insensibility and death has, to the authors’ knowledge, not been studied before. The purpose of this study was to determine, under field conditions, whether a captive bolt shot causes irreversible stunning and death in cattle with a reliability that is acceptable from an animal welfare standpoint and whether the use of a pithing rod could increase the success rate without compromising operator safety.

Materials and methods

Pithing

Pithing is the practice of physically disrupting the brain and rostral part of the spinal cord. The mechanical damage to the brain stem prevents the animal from regaining consciousness and makes the stunning irreversible. Pithing does not compensate for a poorly performed captive bolt shot. It is inhumane to pith an unstunned animal (8).

The pithing rod (pithing cane) used in this study is a flexible plastic rod, approximately 1.0 m in length with a slight curvature (cattle pith rod “Pith+Plug,” Operating Platforms, Bristol, England). The rod is 7 mm in diameter and x-shaped on cross section. One end of the rod has a sponge to absorb body fluids and 5 pairs of barbs to prevent the rod from slipping out, or being removed, once it has been inserted fully into the cranial cavity.

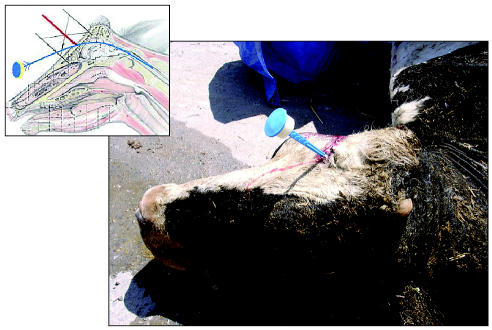

The pithing rod is inserted into the perforation in the forehead made by the captive bolt gun or free bullet. With some manipulation, the rod can be pushed through the neural tissue of the fore- and hindbrain into the spinal canal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the captive bolt position (red arrow) and partial insertion of the pithing rod (blue).

Animals

The rate of occurrence of return to sensibility in cattle euthanized with captive bolt was surveyed. The sample population consisted of cattle, mostly cull dairy cows, over the age of 30 mo condemned as unfit for slaughter after arriving at a Canadian abattoir and destined to be euthanized on-site and sent to a rendering facility. In the course of the survey, all animals were stunned by the same operator using a penetrating captive bolt gun and then randomly assigned to 2 subgroups: A) on which a pithing rod was used after the captive bolt shot, and B) on which a pithing rod was not used after the captive bolt shot.

The animals in the subgroup A were pithed as soon as possible after shooting.

All animals were observed for at least 10 min following euthanasia for signs of return to sensibility. Rhythmic breathing, blinking, blinking reflexes, righting reflexes, vocalizations, or nystagmus are indicative that the stunning is not irreversible and that there has been a return to a degree of consciousness (6).

The time of occurrence of each of these signs was recorded. Following the captive bolt shot, the quantity of blood spillage from each animal was estimated by assessing the size of the spill.

Samples of the obex were taken from each of the animals at the rendering plant and processed as part of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (TSE) surveillance. The impact of pithing on the integrity of obex samples and their suitability as specimens for TSE testing was assessed by the feedback received from the accredited laboratory.

Results

Thirty-two animals were included in the survey: 20 were assigned to Group A, 12 to Group B.

The delay between shooting and pithing ranged between 10 s and 10 min, depending on the position of the animal on the truck, access to the head, and operator safety concerns. Some animals could be pithed only after they had been unloaded from the truck. None of the animals that were pithed returned to consciousness.

Five of the 12 animals that were not pithed exhibited signs of return to consciousness after stunning. In 4 animals, at least 1 of the signs indicative of reversible stunning could be identified immediately after the shot. In 1 animal, rhythmic breathing, vocalization, eye blink response, and spontaneous blinking occurred, beginning 20 min after the captive bolt shot.

Blood loss could be estimated in 20 animals and ranged between 10 mL and 500 mL, with an average of 64 mL. All obex samples from pithed animals that were submitted for TSE testing could be processed by the laboratory as intact specimens.

Discussion

Historically, slaughter workers in Europe pithed cattle to reduce the risk of workers being injured by the uncoordinated movements of stunned animals, particularly when the animal was dressed on the floor (9). Pithing became less common when vertical bleeding and dressing became the norm, but it was still routine in many European slaughter facilities until 2000. No records are readily available that show any significant role of pithing of livestock in the history of North American slaughter operations.

Recent studies have shown that the use of pithing rods after stunning may lead to dissemination of emboli of specified risk material (SRM) from the brain and spinal cord throughout the carcass, including to lung and muscle (10–12). As a consequence, the European Union banned the practice of pithing in animals bound for human consumption (13). Pithing is also a method for euthanasia of reptilians, amphibians, and fish that is approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association (14).

The majority of animals used in this survey were non-ambulatory or moribund, and restraint was excellent. Subject arousal in response to human presence and handling was at a minimum, probably due to the preponderance of dairy animals in this study.

Safety while working around the animals was a major consideration. Cattle frequently kicked or thrashed following captive bolt stunning and during pithing. As a result, pithing was performed while standing on the dorsal side and rostral end of the animal, away from the animal’s legs, and not between the animal’s head and a fixed object. When a stunned animal fell in a manner that made a pithing attempt unsafe for the investigator, the procedure was delayed until the animal could be repositioned or taken off the truck. As a result, the interval between stunning and pithing varied greatly. This variation may mimic actual depopulation operations, where pithing may not always immediately follow stunning. Further studies with standardized stun-to-pith intervals could show whether the time elapsed between stunning and pithing has any impact on the effectiveness of pithing for inducing permanent insensibility.

The scope of the survey did not allow histopathological examination of the brain stem to determine the extent of mechanical disruption caused by the pithing rod. However, the classification of the obex samples as being intact suggests that the damage caused by pithing is not severe enough to render TSE samples useless.

Nonpermanent (reversible) stunning that is not or cannot be followed by rapid exsanguination will lead to unnecessary and prolonged suffering in cattle.

The low cost of single-use pithing rods, the simplicity of their use, and both the efficiency and efficacy in preventing stunned cattle from returning to sensitivity prior to death suggest that this technique should be considered not only in a disease control situation, but whenever a bovine animal has to be euthanized without exsanguination.

References

All electronic links accessed and verified: October 24, 2006

- 1.World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) [homepage on the Internet] Health standards, Terrestial animals, Terrestial Animal Health Code 2006 Contents, Part 1, General provisions, Section 3.7, Appendix 3.7.6. Guidelines for the Killing of Animals for Disease Control Purposes. Available at http://www.oie.int/eng/normes/mcode/en_index.htm Last accessed February 5, 2007.

- 2.DEFRA — Foot and Mouth Disease [homepage on the Internet] Animal Health and Welfare: FMD Data Archive available at warehouse http://footandmouth.csl.gov.uk/ Last accessed February 5, 2007.

- 3.Blokhuis H. Welfare Aspects of the main systems of stunning and killing the main commercial species of animals. EFSA Journal. 2004;45:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manson C. Introduction to modern slaughter methods. Proc Int Training Workshop Welfare Standards Concerning the Stunning and Killing of Animals in Slaughterhouses or for Disease Control. September 26–29, 2006 Bristol. Available from: Humane Slaughter Association, The Old School, Brewhouse Hill, Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire, AL4 8AN, UK.

- 5.Grandin T. Maintenance of good animal welfare standards in beef slaughter plants by use of auditing programs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226:370–373. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.226.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandin T. Return-to-sensibility problems after penetrating captive bolt stunning of cattle in commercial beef slaughter plants. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221:1258–1261. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.221.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory N. Anatomical and physiological principles relevant to handling, stunning and killing red meat species. Proc Int Training Workshop Welfare Standards Concerning the Stunning and Killing of Animals in Slaughterhouses or for Disease Control, September 26–29 2006 Bristol. Available from: Humane Slaughter Association, The Old School, Brewhouse Hill, Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire, AL4 8AN, UK.

- 8.Geering W, Penrith ML, Nyakahuma D. Manual on procedures for disease eradication by stamping out. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2001: Chapter 3. Available at http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/004/Y0660E/Y0660E01.htm#ch1.3.3

- 9.Leach TM, Wilkins LJ. Observations on the physiological effects of pithing cattle at slaughter. Meat Sci. 1985;15:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(85)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anil MH, Love S, Williams S, et al. Potential contamination of beef carcases with brain tissue at slaughter. Vet Rec. 1999;145:460–462. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.16.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horlacher S, Lücker E, Eigenbrodt E. Brain emboli in the lungs of cattle. Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 2002;115:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lücker E, Schlottermüller B, Martin A. Studies on contamination of beef with tissues of the central nervous system (CNS) as pertaining to slaughtering technology and human BSE-exposure risk. Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 2002;115:118–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commission Decision 2000/418/EC of 29 June 2000 regulating the use of materials presenting risks as regards transmissible spongiform encephalopathies and amending decision 94/474/EC. Official Journal of the European Communities L158/77 2000. Available from: http://forum.europa.eu.int/irc/sanco/vets/info/data/oj/00418ec.pdf Last accessed February 5, 2007.

- 14.Beaver BV, Reed W, Leary S, et al. 2000 Report of the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;218:671–696. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]