Abstract

N1-methyladenine (m1A) and N3-methylcytosine (m3C) are major toxic and mutagenic lesions induced by alkylation in single-stranded DNA. In bacteria and mammals, m1A and m3C were recently shown to be repaired by AlkB-mediated oxidative demethylation, a direct DNA damage reversal mechanism. No AlkB gene homologues have been identified in Archaea. We report that m1A and m3C are repaired by the AfAlkA base excision repair glycosylase of Archaeoglobus fulgidus, suggesting a different repair mechanism for these lesions in the third domain of life. In addition, AfAlkA was found to effect a robust excision of 1,N6-ethenoadenine. We present a high-resolution crystal structure of AfAlkA, which, together with the characterization of several site-directed mutants, forms a molecular rationalization for the newly discovered base excision activity.

Keywords: AlkA, Archaeoglobus fulgidus , DNA repair, 1-methyladenine, 3-methylcytosine

Introduction

Enzymatic transmethylation reactions using S-adenosylmethionine as a donor to methylate certain DNA base positions are widespread among organisms. 5-Methylcytosine (m5C) is a minor but significant component of eukaryotic DNA, residing in CpG sequences throughout the genome (Vanyushin et al, 1970). It is considered to play an important regulatory role including gene silencing. In the majority of prokaryotes, m5C and N6-methyladenine protect genomic DNA from digestion by their own restriction endonucleases, and are also involved in repair, replication and expression. Because of its resistance to deamination-induced mutagenesis, N4-methylcytosine replaces m5C in the most thermophilic organisms (Ehrlich et al, 1987). However, erroneous non-enzymatic methylation of DNA (and other macromolecules) by S-adenosylmethionine, as well as by other cofactors, for example, N5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid, also occurs at a slow rate (Barrows and Magee, 1982; Rydberg and Lindahl, 1982). In double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), the major product formed by these reactions is the relatively innocuous N7-methylguanine, followed by N3-methyladenine (m3A). The latter is an important lethal lesion, possibly owing to protrusion of the N3-methyl group into the minor groove of the DNA double helix, thereby blocking DNA replication at the site of the lesion. These and other minor products, such as the similarly cytotoxic N3-methylguanine (m3G) and the O2-alkylpyrimidines, are excised from DNA in vivo by methylpurine-DNA glycosylase (MPG) enzymes (Sedgwick, 2004), leaving behind an apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site. This reaction initiates the so-called base excision repair (BER) pathway (Friedberg et al, 2006), which is predominantly completed by reinsertion of a single nucleotide by the activity of a 5′-acting AP endonuclease, DNA deoxyribophosphodiesterase, DNA polymerase and DNA ligase. O6-alkylguanine and O4-alkylthymine have long been regarded as the most mutagenic lesions owing to their ability to base-pair with thymine and guanine, respectively. They are corrected through direct damage reversal by methyl transfer to a cysteine residue in a DNA alkyltransferase (Sedgwick, 2004).

In adenine and cytosine, the N1- and N3-positions are, respectively, the nucleophilic centers most reactive to alkylating agents. However, since base pairing protects these positions from methylation in dsDNA, the highly toxic N1-methyladenine (m1A) and both mutagenic and toxic N3-methylcytosine (m3C) (Delaney and Essigmann, 2004) are major products in single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) only (Beranek, 1990). Repair of m1A in DNA has eluded scientists for decades (Sedgwick, 2004), but it was recently reported to be carried out by a novel mechanism: oxidative demethylation. This is catalyzed by the AlkB protein and homologues in Escherichia coli and mammals, respectively (Duncan et al, 2002; Falnes et al, 2002; Trewick et al, 2002; Aas et al, 2003). However, some organisms, including the archaeons, lack AlkB homologues, which prompted the question whether other enzymatic mechanisms are involved in m1A repair.

We report here that m1A and m3C, as well as the alkylated base analogue 1,N6-ethenoadenine (ɛA), are all excised with high efficiency from DNA by the MPG enzyme AfAlkA (Birkeland et al, 2002) and are consequently repaired through the BER pathway in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. We present a high-resolution crystal structure of AfAlkA, which, together with the characterization of several site-directed mutants, forms a molecular rationalization for the newly discovered base excision activity. Comparison of the crystal structure of AfAlkA with the structure of AlkA from E. coli (EcAlkA) (Labahn et al, 1996; Yamagata et al, 1996; Hollis et al, 2000) reveals intriguing differences and conservations between the two enzymes.

Results

Excision of m1A, m3C and ɛA from DNA by AfAlkA

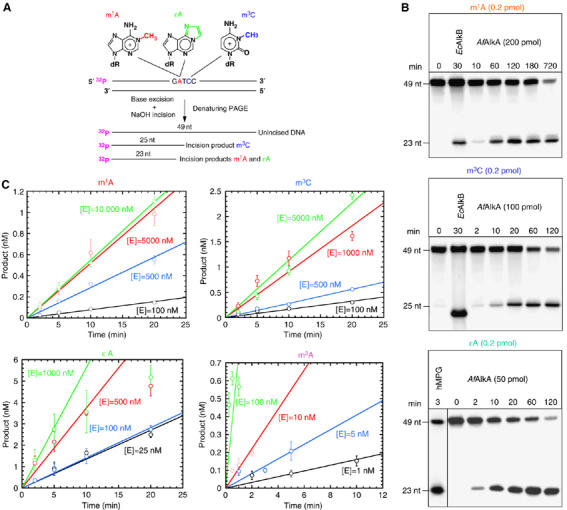

To investigate whether the AfAlkA protein is able to excise m1A, m3C and ɛA from DNA, oligonucleotide substrates containing one of these base lesions inserted at a defined position (Figure 1A) were incubated with enzyme at 70°C (a temperature previously determined to be optimal for the excision of m3A by AfAlkA; Birkeland et al, 2002) for an increasing period of time. To avoid interference from less well-defined factors such as possible product inhibition (released base; AP site) and enzyme inactivation, activity was measured under single-turnover conditions employing enzyme 2–3 orders of magnitude in excess of substrate, as previously have been preferred for analysis of human MPG (hMPG) excision rate (Abner et al, 2001). The presence of repairable base lesions was confirmed by incubating the m1A- and m3C-containing DNA with EcAlkB (Trewick et al, 2002) and the ɛA-containing DNA with hMPG (Abner et al, 2001; Speina et al, 2003). The results showed that AfAlkA exhibits significant activity for the excision of all base lesions examined from DNA (Figure 1B). No excision of m1A or m3C was observed by incubating EcAlkA with substrate at 37°C under similar experimental conditions (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1abc.

Excision of m1A, m3C and ɛA from DNA by AfAlkA. (A) The oligonucleotides containing m1A, ɛA or m3C at a specific position utilized as substrates. The size of the incision products following glycosylase excision of the specified base lesion and base-catalyzed phosphodiester bond cleavage of the resulting abasic site by alkali treatment is indicated. (B) Cleavage of 5′32P-labeled 49-nucleotides (nt) DNA into repair product (23 and 25 nt) is shown, for typical experiments. Incubation with EcAlkB (4.2 pmol) at 37°C was included as a positive control (in the case of m1A, 10 fmol DNA; m3C, 4.2 fmol DNA), where the DpnII cleavage site corresponds to 22 nt (Ringvoll et al, 2006) (not indicated). For excision of ɛA, incubation of 10 fmol DNA with a 26 kDa truncated hMPG protein (O'Connor, 1993) was included as a positive control. (C) Single-turnover kinetics for excision of m1A, m3C and ɛA, where 10 nM of DNA was incubated with the indicated concentrations of AfAlkA at 70°C for increasing time periods. Incubation with MNU-treated DNA (see Materials and methods) was performed under conditions where virtually only m3A is enzymatically excised (Birkeland et al, 2002), using 5000 d.p.m. of methylated DNA bases (∼1 nM of m3A). Each value represents the average of three independent measurements.

To determine kinetic parameters for the excision of m1A, m3C and ɛA from DNA by AfAlkA, a single-turnover kinetic analysis based on certain considerations (presented in Supplementary data) was performed, where the reaction rate v for excision of a single base on a single DNA strand is described by the following equation:

where [DNA]tot is the concentration of active substrate/DNA, [E]tot is the total concentration of the enzyme, k2 is the turnover number and KD=(k−1+k2)/k1. KD is analogous to the Michaelis constant KM describing the steady state (or rapid equilibrium) between substrate and the enzyme-substrate complex (see Supplementary data).

The reaction rate v was determined by the slopes of the linear regression curves presented in Figure 1C. Dividing the rate by the active substrate concentration [DNA]tot leads to a first-order rate constant k, which describes the overall accumulation of product P during the excision:

The amount of cleavable DNA (i.e. the active substrate concentration [DNA]tot) was determined by fitting the experimental [P] – time plots presented in Figure 1D to equation (2)), where the concentrations approached 5.3±0.1 nM for m1A, 6.4±0.3 nM for m3C, 8.2±0.2 nM for ɛA and 0.63±0.02 nM for m3A. The rate constant k is dependent on the total enzyme concentration as shown in equation (3) (see Supplementary data for derivation):

Figure 1de.

(D) Plots of product formation as a function of time ([P]–time plots, together with a curve fit of equation (2) to the experimental data, to determine the active substrate concentration [DNA]tot (see Results)). (E) Calculated k values (determined from the slopes of the curves presented in C) as a function of [E]tot, together with a curve fit of equation (3) to the experimental data (see Results).

Experimental results are in good agreement with equation (3). k values determined as function of [E]tot are presented in Figure 1E, together with a curve fit of equation (3) to the experimental data. From this, k2 and KD for the different substrates were estimated (Table I).

Table 1.

Single-turnover kinetic parameters of AfAlkAa

| Parameter | Entity | Substrate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1A | m3C | ɛA | m3A | ||

| Wild type | |||||

| k2 | min−1 | 0.0109±0.0002 | 0.022±0.004 | 0.12±0.02 | 3.9±0.8 |

| KD | nM | 530±40 | 900±500 | 700±200 | 230±60 |

| Gln128Ala | |||||

| k2 | min−1 | 0.011±0.001 | 0.058±0.004 | ||

| KD | nM | 1300±500 | 170±50 | ||

| Phe133Ala | |||||

| k2 | min−1 | 0.008±0.002 | 0.037±0.001 | ||

| KD | nM | 7000±4000 | 220±30 | ||

| Phe282Ala | |||||

| k2 | min−1 | 0.0084±0.0009 | 0.046±0.004 | ||

| KD | nM | 4000±1000 | 160±50 | ||

| Phe133Ala/Phe282Ala | |||||

| k2 | min−1 | ≈5 × 10−7 KD | 0.008±0.001 | ||

| KD | nM | ≫10 000 | 400±200 | ||

| Arg286Ala | |||||

| k2 | min−1 | 0.027±0.003 | 0.033±0.001 | ||

| KD | nM | 4000±1000 | 280±30 | ||

| Asp240Ala | |||||

| k2 | min−1 | Not detectable | Not detectable | ||

| aBecause KD values depend on the binding kinetics between DNA and the enzyme, a precise interpretation of the physical nature of KD is difficult to make. See Supplementary data section for a more detailed discussion. | |||||

The results show that AfAlkA excises m3C (k2=0.022±0.004 min−1) from DNA about twice as fast as m1A (k2=0.0109±0.0002 min−1). The rate for ɛA (k2=0.12±0.02 min−1) is further 5–10 times higher (Figure 1E). The results also indicate m3A as the principal substrate for AfAlkA, although the nature of the DNA in this case makes a direct comparison to the other three damaged bases inaccurate.

Overall structure and comparison with EcAlkA

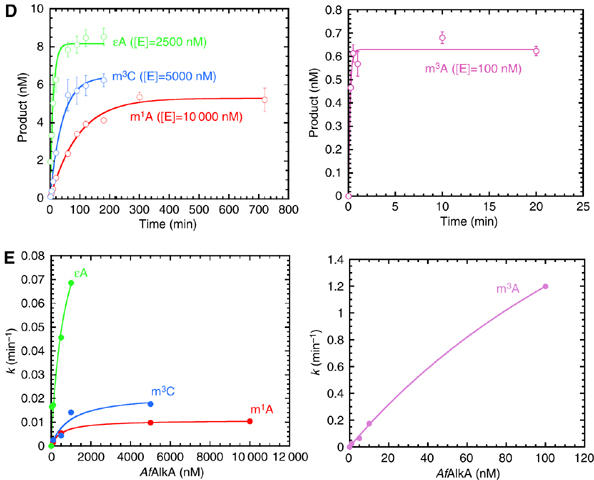

The crystal structure of AfAlkA was determined using the single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) method on a mercury-soaked crystal. Redundant diffraction data to 1.8 Å resolution, collected on the absorption peak of the mercury LIII edge were sufficient to solve the structure. The native structure was thereafter determined by molecular replacement using data collected to 1.9 Å resolution on a native crystal. Of the 295 amino-acid residues, 289 from each of the two protein monomers in the asymmetric unit were ordered and included in the refinement. In addition, 2–3 residues in the C-terminus were observed to interact with a symmetry molecule and were modeled with reduced occupancy. This interaction is most likely an artifact of the crystal packing. Crystallographic data are presented in Supplementary Table I. The two monomers in the asymmetric unit overlay with a root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 0.24 Å for all Cα atoms. Similar to the helix–hairpin–helix (HhH) protein EcAlkA (Labahn et al, 1996), AfAlkA has a relatively compact globular structure, with overall dimensions of about 35 Å by 40 Å by 50 Å. AfAlkA is a three-domain protein, where the N-terminal domain, comprising residues 1–81, consists of a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (βA–βE) with two α-helices adjacent to the β-sheet (αA–αB; Figure 2A and B). Two helices (αC–αD), comprising residues 82–109, are close to the C-terminal domain. The central domain is mainly helical and consists of residues 110–236 in a total of eight α-helices (αE–αL). Two short β-strands (βF–βG; residues 148–161) protrude from the middle domain, contacting strands βC–βE in the N-terminal domain. A short linker region connects the middle domain with the C-terminal domain, which comprises residues 237–289, forming the three last α-helices in the protein (αM–αO). A study on EcAlkA in complex with DNA containing a modified abasic nucleotide, 1-azaribose (Hollis et al, 2000), established the HhH motif to be important for DNA binding. In AfAlkA, this motif is located in the C-terminal part of the central domain, comprising residues 205–229 in α-helices αK–αL (colored green in Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Structure of AfAlkA. β-Strands are shown in blue and α-helices in red (except for the two α-helices forming the HhH motif, αK–αL, which are shown in green). (A) Stereo representation of the overall ribbon structure. (B) Primary and secondary structures of AfAlkA (above) aligned with EcAlkA (below). Identical amino-acid residues are boxed in blue, whereas structurally conserved residues are highlighted in gray. AfAlkA residues investigated by site-directed mutagenesis are indicated by an asterisk. The sequence alignment in (B) is based on a structural alignment of the crystal structures. The secondary structure elements of AfAlkA are indicated above the alignment, whereas those of EcAlkA are indicated below.

Two metal ions with octahedral coordination were identified in electron density in each monomer of AfAlkA. These were modeled as sodium, according to mean bond distances of 2.43 Å (2.42 Å) to water ligands and 2.44 Å (2.46 Å) to main-chain carbonyl atoms (where numbers in parentheses are the expected distances), as well as its presence as the major cation (0.3 M) during purification (Harding, 2006). One sodium ion is located in proximity to the αA–βB loop of the N-terminal domain and is coordinated by the carbonyl oxygens of Leu21, Pro22, Leu24 and Asp28, the side-chain oxygen of Thr26 and a water molecule. This ion is most likely important only in stabilizing the folded state of the protein. The other sodium ion is located in proximity to the HhH region and will be described in more detail later.

AfAlkA and EcAlkA share 20.5% amino-acid sequence identity, and similarity in secondary structure is indicated by their native crystal structures (Supplementary Figure 2) (Labahn et al, 1996; Yamagata et al, 1996), where 159 residues can be superimposed with an overall r.m.s.d. of 1.58 Å for Cα atoms. Highest structural similarity is within the central domain, where Gly112–Leu241 of AfAlkA overlaps with Leu107–Tyr239 of EcAlkA (Figure 2B). However, larger conformational differences are observed between the N- and C-terminal regions of the proteins (Supplementary Table II and Supplementary Figure 2), explaining why the crystal structure of AfAlkA could only be determined by experimental phasing methods.

A three-dimensional structural homology search using DALI (Holm and Sander, 1993), with one monomer of AfAlkA as the search template, resulted in structural hits for several HhH proteins. As expected, EcAlkA showed the highest similarity with a Z-score of 28.2, followed by the bifunctional human 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase/lyase (hOGG1) (Bruner et al, 2000) with a Z-score of 20.7. The sequence of hOGG1 comprises 345 amino acids sharing ∼17% identity with that of AfAlkA. The HhH motifs of the three proteins align particularly well and a more detailed comparison was therefore performed as described later.

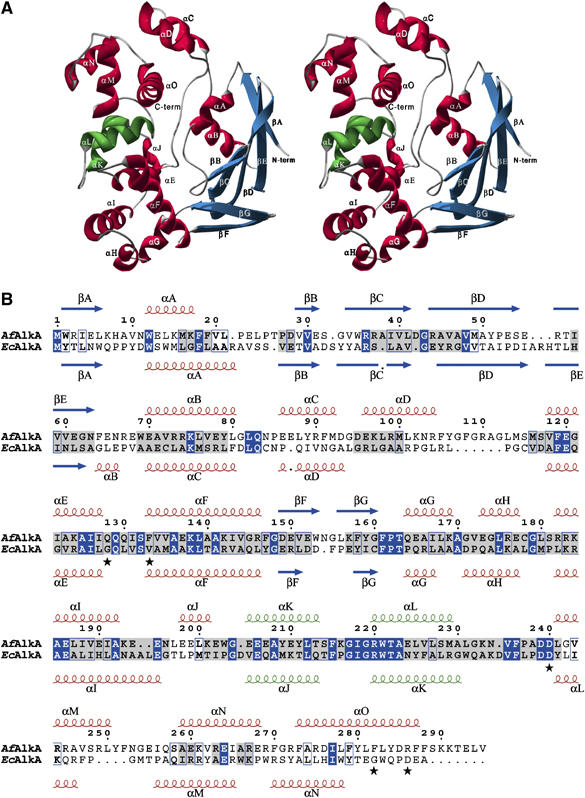

The DNA-binding region

There are numerous amino-acid substitutions in the active site region and in the DNA-binding area of AfAlkA compared with EcAlkA (Figure 3A–D). On the other hand, the extensively conserved hairpin region of the HhH motif (Figure 2B) suggests a retained overall mode of enzyme–DNA binding. Superimposing the crystal structures of AfAlkA and EcAlkA, when the latter is in complex with a modified AP-site DNA (Hollis et al, 2000), specifies the DNA-contacting residues of AfAlkA (Figure 3A and B), showing a conserved mode of contacting and bending (>60°) DNA. A requirement for dsDNA is indicated, since both enzymes seem to possess more and stronger charged interactions with the complementary strand than with the damage-containing strand, along with amino-acid residues forming van der Waals interactions to the DNA minor groove. The number of positively charged residues putatively in contact with the phosphate backbone of the complementary strand appears to be slightly higher in AfAlkA (Lys138, Lys142, Arg176 and Arg182) compared with EcAlkA (Lys133, Arg137 and Lys170). In addition to the positively charged Arg245 and Lys216 expected to strengthen AfAlkA–DNA binding, the damage-containing strand appears to almost exclusively form polar interactions with the protein backbone and a sodium ion present in proximity to the hairpin loop of the HhH motif. This ion is coordinated by three main-chain protein contacts (the carbonyl oxygens of Thr213, Phe215 and Ile218) as well as three water molecules, and may mediate DNA phosphate backbone interactions, as suggested for a similarly coordinated sodium ion in EcAlkA. The latter is coordinated by the main-chain carbonyl oxygens of the structurally conserved Gln210, Phe212 and Ile215 (EcAlkA numbering) (Hollis et al, 2000). AfAlkA and EcAlkA have similar electrostatic surface potentials (Figure 4A and B), which also may relate to their overall DNA-binding strength.

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of (A) EcAlkA in complex with DNA containing the modified abasic nucleotide 1-azaribose (Hollis et al, 2000) and (B) AfAlkA, including an enlarged view of their respective active site regions (C, D). The damage-containing strand is shown in cyan and the complementary strand is shown in yellow. The HhH motif of EcAlkA and AfAlkA is colored dark blue, whereas the amino-acid residue replacing the flipped-out nucleotide is colored red in (A and B). In (D), an ɛA moiety has been modeled into the substrate-binding pocket of AfAlkA, with the molecular surface of the ɛA moiety shown in atom colors. Furthermore, the AfAlkA residue Arg286 is flexible and, as a consequence, was refined in two conformations, indicated in (D).

Figure 4.

Estimated electrostatic surface potential of (A) EcAlkA and (B) AfAlkA colored according to electrostatic potential at a contour level of ±7 kBT (blue, positively charged; red, negatively charged). The damage-containing strand is shown in light blue and the complementary strand in yellow. The DNA fragment from the EcAlkA–DNA complex structure has been modeled to fit to the AfAlkA DNA-binding region in (B).

Amino-acid residues involved in damage detection and binding

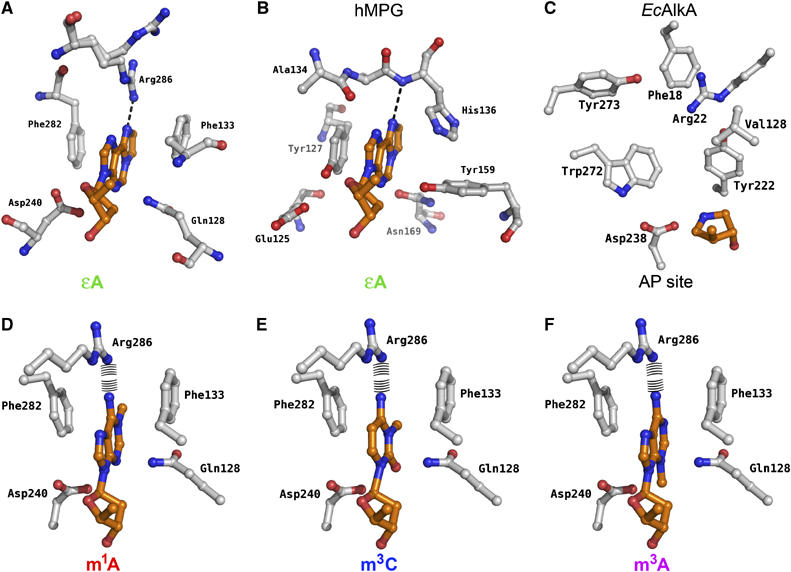

As indicated by sequence analysis (Birkeland et al, 2002), the crystal structures of AfAlkA (Figure 3B) and EcAlkA (Figure 3A) demonstrate several differences in the composition of the active site (Figure 3C and D). As EcAlkA and hOGG1 were found to have the highest structural similarity to AfAlkA, their crystal structures were utilized to identify conformational similarities and potential differences between the three proteins. Although superimposing the DNA backbone of the hOGG1-DNA (Bruner et al, 2000) and EcAlkA-DNA (Hollis et al, 2000) complexes results in a reasonably good match, the orientation of the two active site grooves indicates that the flipped-out damaged bases will be oriented in different ways. Furthermore, the aromatic residues in the substrate-binding pockets of EcAlkA and AfAlkA will direct rotation of the substrate base at roughly 90°, compared with its orientation in hOGG1. Aromatic residues are electron donors attracting the damaged, and in most cases electron-deficient, alkylated DNA base. Such π–π (or π–cation in the case of positively charged bases) interactions have been suggested to be important in the recognition and binding of alkylated base lesions (Eichman et al, 2003) (Figure 5A–F). In AfAlkA, base stacking appears to be more pronounced than in EcAlkA (Figure 3C and D), with Phe133 and Phe282 ideally positioned in the binding pocket to form interactions with the flipped-out substrate base (Figure 3D). The binding pocket of EcAlkA (Figure 3C) possesses less-optimized residues (Val128 and Trp272) in order to attract damaged bases (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Substrate-binding pockets of (A) AfAlkA with ɛA modeled into the substrate-binding pocket and (B) hMPG crystallized in complex with an ɛA-containing DNA fragment. The ɛA moiety is indicated with orange carbon atoms. The dotted line indicates the potential hydrogen bond between the damaged base and the protein. (C) Binding pocket of EcAlka crystallized in complex with DNA containing 1-azaribose. (D–F) AfAlkA binding pockets with m1A, m3C and m3A modeled, otherwise as above. The potential repulsion between Arg286 and the amine of the damaged base is indicated.

Arg286 provides binding strength and productive orientation of substrate by forming a hydrogen bond specifically with the ɛA base (Figure 5A), where the N6 nitrogen of ɛA projects a lone pair in the direction of the NH2+ (Nη2) arginine side chain. This may also explain the efficiency of hypoxanthine, the deamination product of adenine, as a substrate for AfAlkA (Mansfield et al, 2003). In this case, an oxygen atom (O6) instead of a nitrogen atom (N6) provides the lone pair. The equivalent position (N6) of m1A is unable to accept a proton necessary to form a similar interaction with Arg286 (Figure 5D), which also is the case for the N4 atom of m3C being in a spatially overlapping position (Figure 5E). The m1A/m3A-N6 and m3C-N4 amine groups are protonated and potentially cause repulsion of the protonated side chain of Arg286 (Figure 5D–F).

The substrate-binding pocket of AfAlkA indicates some selectivity against naturally occurring purine bases. While adenine has a protonated N6 amine, causing repulsion of Arg286 (as described for m1A, m3C and m3A) (Figure 5D–F), guanine has an oxygen atom at this position, which would be able to form stabilizing interaction with Arg286. However, guanine is aminated in its C2 position, which is likely to cause repulsion of the hydrophobic side chain of Leu225, with its closest atoms (Cδ1 and Cδ2) less than 2.8 Å away from the amine group. The AfAlkA Leu225 is conserved in most thermophilic AlkA-type sequences (data not shown), as opposed to EcAlkA, where Tyr222 occupies the overlapping position and thus probably serves a similar purpose. It is interesting to note that Arg286, which like Leu225 is conserved among thermophilic sequences, is close to the C-terminus of AfAlkA, whereas the residue occupying the corresponding position in EcAlkA, Arg22, belongs to the N-terminal domain (Figures 2B and 3C and D). These two residues are likely to play similar roles in substrate binding and discrimination.

Surprisingly, the substrate-binding pocket of AfAlkA is ‘open-ended', with 13 water molecules and one glycerol molecule located in its extension, which is branched, with branch lengths of around 11 Å in each direction (Supplementary Figure 3). The function of this internal water channel in AfAlkA is yet to be identified.

Site-directed mutagenesis of amino-acid residues involved in substrate binding and catalysis

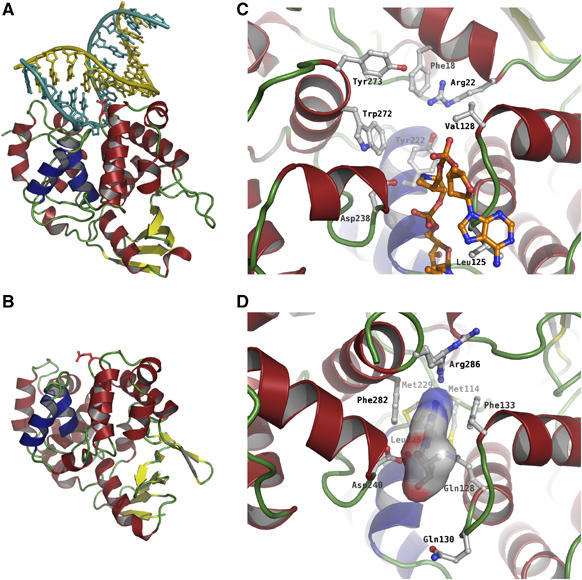

Based on the crystal structure of AfAlkA, several site-directed mutants were designed (Table II). The mutants were selected to verify the DNA-bound model built by superpositioning AfAlkA on the DNA–EcAlkA complex, and to explain the substrate specificity of AfAlkA. Following purification of each mutant protein to apparent homogeneity (Supplementary Figure 4), their activities were assayed under single-turnover conditions using the m1A (Supplementary Figure 5) and ɛA (Supplementary Figure 6) substrates (Figure 6A and B). As for wild-type AfAlkA, k2 and KD were estimated (Table I).

Table 2.

Proposed functions of the mutated residues of AfAlkA

| Mutation | Proposed function in wild-type protein |

|---|---|

| Gln128Ala | Accommodation of ɛA in binding pocket |

| Phe133Ala | π–cation/π–π/van der Waals contact with aromatic ring structure of DNA base |

| Asp240Ala | Catalytic residue |

| Phe282Ala | π–cation/π–π/van der Waals contact with aromatic ring structure of DNA base |

| Arg286Ala | Repulsion of protonated adenine N6 and m3C N4; H-bond to ɛA and hypoxanthine |

Figure 6.

Single-turnover kinetics for excision of m1A (A) and ɛA (B) by mutant AfAlkA proteins using the conditions described in Figure 1(A)–(C) and (D). Each value represents the average of 2–4 independent measurements.

As indicated by structural analysis, the importance of Phe133 and Phe282 for substrate binding was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis. For excision of m1A, k2 decreased only moderately (to ∼75% of wild-type value) by replacing one phenylalanine, whereas activity was almost totally knocked out by replacing both with Ala (Table I and Figure 6A): the rate measurement of the Phe133Ala/Phe282Ala protein approached the lower detection limit (Supplementary Figure 5 and Table I). In conclusion, one aromatic residue only (where Phe133 and Phe282 seem equally suitable) is necessary to accommodate m1A (and most likely also other positively charged bases) productively in the substrate-binding pocket (Figure 5D–F), verifying the strength of the π–cation interaction. Replacing one or both phenylalanines with alanines decreased the wild-type value of k2 for excision of ɛA to 30–40 or 7%, respectively (Table I), demonstrating that both Phe133 and Phe282 are desirable for productive binding of ɛA to AfAlkA (Figure 6B).

Because π–cation interactions are replaced by weaker π–π/van der Waals interactions when AfAlkA binds neutral substrates such as ɛA and hypoxanthine, the required extra stabilization in the active site pocket is provided by hydrogen bonding to Arg286 (Figure 5A). This structural characteristic is nicely confirmed by the observation that the k2 for excision of ɛA by the Arg286Ala protein decreased to ∼30% of the wild-type value (Table I). This contrasts with the activity for m1A (Figure 6A), where k2 more than doubled by introduction of the neutral Ala instead of the positively charged Arg, by neutralizing the repulsion of this positively charged base in the active site pocket (Figure 5D).

The Gln128Ala replacement had no significant effect on the excision rate of m1A (Figure 6A and Table I), indicating little interference between m1A and Gln128 (Figure 5D). This contrasts with the excision rate for ɛA (Figure 6B), where k2 decreases to the half of the wild-type value (Table I). This can be explained by the fact that whereas m1A and other positively charged bases need little catalytic power for excision, as proposed for excision of base lesions by EcAlkA (O'Brien and Ellenberger, 2004), the much more stably DNA-bound ɛA lesion requires a more precise positioning in the substrate-binding pocket to be liberated. Since this residue seems to restrict accessibility to the substrate-binding site (Figure 5A), it may have a function in substrate selection, although Gln128 is clearly important for coordination of ɛA in the substrate-binding pocket.

In EcAlkA, Asp238 has been indicated as the catalytically critical residue by site-directed mutagenesis to Asn (Labahn et al, 1996; Yamagata et al, 1996). Consequently, the structurally equivalent Asp240 of AfAlkA was mutated to Ala, resulting in virtually total loss of enzyme function on all substrates tested (data not shown). Although the measurements were performed using huge excess of enzyme (10 fmol of m1A and ɛA substrates with 60 and 15 pmol AfAlkA, respectively, at 70°C for 30 min; ∼0.06 pmol of m3A present in MNU-treated DNA with 15 pmol AfAlkA at 70°C for 10 min), the activity was at the limit of detection. This strongly indicates that Asp240 is needed either for nucleophilic attack on the C1′ of deoxyribose or for stabilizing a reaction intermediate, although the exact role of this residue in AfAlkA (as for Asp238 in EcAlkA) remains unclear for the moment.

Discussion

In normal B-form DNA, Watson–Crick base pairing protects the 1-position of adenine and the 3-position of cytosine from alkylation exposure. However, m1A is a major and m3C a minor methylation product in single-stranded regions of cellular DNA, which are frequently formed during replication and transcription (Sedgwick, 2004). Their significant toxicity and mutagenicity (Delaney and Essigmann, 2004) thus necessitate their repair in all types of tissues. Although the presence of m1A and m3C in DNA has been known for decades, a mechanism for their removal was only recently elucidated as a novel form of direct damage reversal described as oxidative demethylation, catalyzed by the E. coli AlkB protein and mammalian homologues (Duncan et al, 2002; Falnes et al, 2002; Trewick et al, 2002; Aas et al, 2003). Etheno lesions were thereafter also found to be repaired by this mechanism (Delaney et al, 2005). To date, no BER glycosylases have been reported to excise m1A or m3C from DNA.

However, several organisms, including the hyperthermophilic archaeon A. fulgidus, contain no alkB homologue (Klenk et al, 1997). We therefore aimed to investigate whether other mechanisms might be involved in the repair of m1A and m3C in DNA. One likely candidate was the AfAlkA glycosylase characterized by our research group, which excises m3A, m3G, m7A and m7G from DNA exposed to methylating agents (Birkeland et al, 2002). Intriguingly, we found that AfAlkA showed significant activity for excision of both m1A and m3C from DNA (Figure 1B). This contrasts with EcAlkA, which exhibited no activity for these lesions (Supplementary Figure 1), as previously reported for m1A in alkylation-exposed poly(dA) and poly(dA)/poly(dT) (Bjelland and Seeberg, 1996). The kinetic parameters determined for AfAlkA (Table I) demonstrate that the catalytic efficiency for m1A and m3C is comparable to that for the removal of other lesions by DNA glycosylases measured under single-turnover conditions (Abner et al, 2001; O'Neill et al, 2003), indicating that m1A and m3C are repaired by the BER pathway in A. fulgidus. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating enzymatic excision of 1-methylated purines or 3-methylated pyrimidines from DNA. We also found that ɛA, another type of base damage repaired by both AlkB- (Delaney et al, 2005) and MPG-type (Abner et al, 2001) enzymes, is efficiently excised from DNA by AfAlkA (Figure 1B and Table I). In an accompanying report, we describe the whole BER pathway of A. fulgidus (I Knævelsrud, GT Haugland, K Grøsvik, A Klungland, N-K Birkeland and S Bjelland, in preparation).

Careful determination of the turnover number (k2) for the base lesions studied shows that AfAlkA excises ɛA 5–10 times more efficiently than m1A and m3C from DNA (Table I). This makes it tempting to speculate whether ɛA may be formed in higher amounts than the other two lesions at the high-temperature and anaerobic growth conditions of A. fulgidus. The kinetic data also confirm m3A as a major substrate for AfAlkA (Birkeland et al, 2002), exhibiting a k2 about 30 times higher than for ɛA (Table I). This can partly be explained by the severe instability of the glycosyl bond of m3A requiring little catalytic power for its excision (O'Brien and Ellenberger, 2004), although the different nature of the m3A compared with the other DNA substrates makes a comparison inaccurate.

To explain the novel substrate specificity demonstrated for AfAlkA compared with EcAlkA, AfAlkA was crystallized and subjected to X-ray diffraction and docking analyses. The results of structural comparisons indicated that two main factors are important for a damaged base to be accepted into the AfAlkA binding pocket: (1) while the electron-deficient m1A, m3C and m3A are attracted into the binding pocket by π–cation interactions, that is, electrons projected by the aromatic residues Phe133 and Phe282 at the wall of the pocket (Figure 5D–F), these residues only provide weaker π–π and van der Waals interactions with neutral substrates like hypoxanthine (Mansfield et al, 2003) and ɛA (Figure 5A). Nonetheless, these interactions are also considered important in order for neutral substrates to be excised efficiently by AfAlkA. (2) Hypoxanthine and ɛA will be able to form a stabilizing hydrogen bond with the side chain of Arg286 (not formed by m1A, m3C and m3A). Concluded from the active site structure, AfAlkA should thus be able to excise all the above-mentioned damaged DNA bases. Site-directed mutagenesis indicates that only one aromatic residue (Phe133 and Phe282 seem equally suitable) is necessary to accommodate m1A (and possibly other positively charged bases) productively (at 70°C) in the substrate-binding pocket (Figure 5D–F), verifying the strength of a π–cation interaction. In fact, several other glycosylases, like the structurally conserved EcAlkA and hMPG (which except for the substrate-binding pocket is structurally dissimilar to AfAlkA), contain only one aromatic residue, where a valine (Figure 5C) or a slightly tilted histidine (Figure 5B), respectively, has ‘replaced' the other. By contrast, both Phe133 and Phe282 are needed for productive binding of ɛA to AfAlkA. Thus it is tempting to speculate whether the sandwiching of a damaged base between two aromatic side chains in the active site of AfAlkA has primarily evolved to accommodate neutral lesions, and not positively charged base products, at (hyper)thermophilic temperatures. The importance of such ‘aromatic sandwiching' for alkylated base binding has previously been demonstrated by site-directed mutagenesis of one of the two residues serving this purpose in Helicobacter pylori MagIII glycosylase (Trp24 and Phe45) (Eichman et al, 2003). Replacement of Phe45 with the larger Trp side chain increased activity ∼1.5–2 times, depending on the nature of the substrate base. Site-directed mutagenesis also confirmed the importance of Arg286 (Figure 5A) to provide extra stabilization in the active site pocket of neutral substrates when π–cation interactions are replaced by weaker π–π/van der Waals forces (point (2) above). Replacement of Arg286 with Ala decreased the activity for ɛA by ∼70%, whereas the rate of excision of m1A rather increased (Table I), owing to elimination of the repulsion of this positively charged base in the active site pocket (Figure 5D–F). Importantly, Arg286 probably also causes repulsion of the protonated N6 amine of adenine, thus exclusion of this natural base from the pocket. This is similar to the anticipated repulsion of the aminated C2 position of guanine caused by the hydrophobic side chain of Leu225 (see Figure 3D). By contrast, specific discrimination against adenine is not evident for the MagIII protein mentioned above. Here, increased surface area and hence higher binding energy of ɛA compared with adenine, upon stacking between two aromatic groups, might provide sufficient discrimination (Eichman et al, 2003).

The crystal structure of AfAlkA as well as amino-acid sequence alignments (Figure 2B) suggest Asp240 as a catalytic residue (Figure 5A), which appears to be structurally conserved within the HhH superfamily. In monofunctional glycosylases, this residue is proposed to activate a water molecule for nucleophilic attack on the C1′ deoxyribose carbon to replace the damaged base, whereas in bifunctional enzymes, it is believed to activate a catalytic lysine (Labahn et al, 1996). The undetectable or very low activity of the Asp240Ala mutant protein is in line with this notion (data not shown), as shown for the corresponding mutant protein of EcAlkA (Labahn et al, 1996; Yamagata et al, 1996). However, in contrast with the crystal structure of hMPG, where a water nucleophile is positioned for activation by Glu125 (Lau et al, 1998) (Figure 5B), no obvious candidate for a water nucleophile has been identified in AfAlkA. While numerous water molecules were found in the substrate-binding pocket, none of these appears to be positioned for activation by Asp240, resulting in an attack of the deoxyribose C1′ atom of the damaged base following an SN2-type catalytic mechanism. Our results are thus similar, although not as clearcut as what has been reported for EcAlkA (Hollis et al, 2000), where modeling of a damaged base left no room for a catalytic water molecule, leading to the suggestion that EcAlkA follows an SN1-type catalytic mechanism. In EcAlkA, the catalytic Asp238 residue is suggested to stabilize a carbocation intermediate by directly interacting with the C1′ atom of the ribose moiety. Although this may be sufficient to excise the positively charged alkylated bases typically serving as EcAlkA substrates, AfAlkA, in contrast to EcAlkA, also efficiently removes neutral bases like ɛA (this report) and hypoxanthine (Mansfield et al, 2003) (both with stable glycosyl bonds). This suggests the existence of a residue acting as a general acid to protonate the leaving base as well as a direct SN2 displacement reaction for AfAlkA. It is tempting to speculate whether this is compensated for by an increased glycosyl bond labilization at high temperatures. However, this may be disputed by the fact that AfAlkA also works quite efficiently at mesophilic temperatures (Birkeland et al, 2002), suggesting a common catalytic mechanism for AfAlkA in its whole temperature range.

When EcAlkA binds its dsDNA substrate, Leu125 replaces the flipped-out base and stacks between the neighboring bases on the damage-containing strand. It thus participates in stabilizing the reaction intermediate through improved DNA binding (Figure 3C). This interaction may also be responsible for the severe distortion observed in the region surrounding the flipped-out nucleotide (Hollis et al, 2000). Replacement of the structurally equivalent Gln130 of AfAlkA (Figure 3D) with Leu resulted in significantly decreased activity against m1A and ɛA (data not shown), raising the question whether possible contacts made by a polar amide group to the vacant base following damaged base flipping were disrupted. However, more data are needed to conclude on this issue.

AfAlkA and EcAlkA have a similar number and conserved spatial arrangement of putative DNA-contacting residues. In addition, a sodium ion found to interact with the phosphate backbone in the EcAlkA–DNA complex (Hollis et al, 2000) is bound in a similar position in AfAlkA, coordinated by structurally conserved main-chain contacts in the hairpin region of the HhH motif. Furthermore, the similar electrostatic surface potentials of the two proteins (Figure 4A and B) also suggest a similar DNA-binding mode.

Structural data suggest that both enzymes possess more and stronger charged interactions with the complementary than the damage-containing strand. Along with protein residues forming van der Waals interactions to the DNA minor groove, this indicates a requirement or preference for dsDNA. This has been shown for the excision of hypoxanthine by AfAlkA (Mansfield et al, 2003) and for EcAlkA-catalyzed excision of m3A from alkylation-exposed poly(dA) and poly(dA)/poly(dT) (Bjelland and Seeberg, 1996). The former study showed that AfAlkA binding to DNA is sensitive to mismatches neighboring the site of damage, that is, the introduction of mismatches both 5′ and 3′ to the damaged base almost completely abolishes excision by AfAlkA. Furthermore, no excision was observed when damaged bases were introduced at the end of an oligonucleotide, showing that AfAlkA requires at least two paired bases 5′ and four paired bases 3′ to the damaged site (Mansfield et al, 2003).

Materials and methods

Expression of afalkA wild-type and mutant genes and purification of the corresponding proteins

Amplification and overexpression of wild-type and mutant afalkA genes in E. coli BL21 CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA; containing the genes for the rare E. coli tRNAs recognizing AGA and ATA) harboring pET-11a/af2117 and subsequent purification of the corresponding proteins were performed as previously described (Birkeland et al, 2002). Essentially, cell extract was prepared using French press (900 psi) or sonication (30 min) followed by heat treatment (70°C for 20 min) and centrifugation (10 000 g for 15 min). The supernatant was separated on HiTrap SP Sepharose columns (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with 50 mM Mes [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid)], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 5% (v/v) glycerol (pH 6). The wild-type AfAlkA and the mutants all eluted at around 0.1–0.4 M NaCl (1 ml each) and each fraction was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Supplementary Figure 4).

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutations were introduced into the wild-type afalkA gene present in the pET-11a/af2117 plasmid (Birkeland et al, 2002) by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based method (QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit, Stratagene), employing the appropriate primers with mutations at amino-acid residue positions 128, 133, 240, 282 and 286: Gln128Ala (forward, 5′-GCATTGCCAAGGCCATCATAGCCCAGCAAATCTCTTTCGTAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTACGAAAGAGATTTGCTGGGCTATGATGGCCTTGGCAATGC-3′), Phe133Ala (forward, 5′-CATACAGCAGCAAATCTCTGCGGTAGTTGCGGAGAAACTTG-3′; reverse, 5′-CAAGTTTCTCCGCAACTACCGCAGAGATTTGCTGCTGTATG-3′), Asp240Ala (forward, 5′-GTTTTTCCAGCAGATGCCCTTGGCGTGAGGAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCTCCTCACGCCAAGGGCATCTGCTGGAAAAAC-3′), Phe282Ala (forward, 5′-GGGACATACTGTTCTACCTCGCTCTCTACGACAGATTTTTTAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTAAAAAATCTGTCGTAGAGAGCGAGGTAGAACAGTATGTCCC-3′) and Arg286Ala (forward, 5′-CTCTTTCTCTACGACGCATTTTTTAGTAAAAAGACA-3′; reverse, 5′-TGTCTTTTTACTAAAAAATGCGTCGTAGAGAAAGAG-3′). The reaction mixture was treated with DpnI and amplified DNA was transformed into XL1-Blue Supercompetent Cells using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Correct nucleotide sequence of inserts was confirmed by sequencing both DNA strands.

DNA substrates

The following 49 nt DNA sequence with one m1A, ɛA or m3C site-specifically inserted (underlined) was annealed to an equimolar amount of its complementary strand (3.5 pmol/μl; T opposite m1A and ɛA, G opposite m3C) and employed as substrate (Figure 1A): 5′[32P]-TAGACATTGCCATTCTCGATAGGATCCGGTCAAACCTAGACGAATTCCG-3′. Radiolabeling was performed using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Stratagene) and [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, Amersham) followed by separation on a non-denaturing (m1A and m3C) or denaturing (ɛA) polyacrylamide (PAGE) gel (20%; 300 V, 2.5 h) and purification by ethanol precipitation. Specific activity of substrate (in c.p.m.) was determined in triplicate by scintillation counting (1 μl substrate or [γ-32P]ATP placed in a 6 ml scintillation tube). Substrate concentration (fmol/μl) was calculated according to a formula recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham).

Calf thymus DNA treated with [3H]N-methyl-N′-nitrosourea (MNU; 18.4 Ci/mmol, code TRT785, batch 4, GE Healthcare) (Alseth et al, 2005) was prepared as described.

Assays for incision of DNA

Substrate DNA (10 nM) was incubated with AfAlkA protein in 52 mM Mops [3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid], pH 7.5, 0.75 mM EDTA, 0.75 mM dithiothreitol, 3.75% (v/v) glycerol and 120 mM KCl (final volume 20 μl) at 70°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 20 mM EDTA, 0.5% (w/v) SDS and proteinase K (190 μg/ml) followed by ethanol precipitation. Abasic sites were cleaved by adjusting the samples to a final concentration of 0.1 M NaOH and incubating at 90°C for 30 min. The AlkB assay was performed at 37°C for 30 min in a final volume of 50 μl, as previously described (Ringvoll et al, 2006). Samples were prepared for electrophoresis by adding 10 μl loading solution (80% formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA and 0.05% xylene cyanol), incubated at 95°C for 5 min and cooled on ice. Reaction products were loaded onto a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and electrophoresed at 300 V for 3 h. Gels were fixed in 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid and 4% glycerol followed by vacuum drying for 30 min at 80°C in Hoefer drying equipment and exposure of radioactive gels in a phosphorimager screen cassette overnight. Visualization and quantification were performed by phosphorimaging analysis using ImageQuant Software (Molecular Dynamics Inc.). A decade marker (7 μl) diluted to 1:100 was also loaded onto the gel as a size marker. Experimentally determined rate constant values (k) were fitted to equation (3) by means of the program KaleidaGraph (www.synergy.com).

Crystallization and data collection

AfAlkA was crystallized by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 1 μl-drops of the protein solution (18 mg/ml) with 50 mM Mes, pH 6. The drops were equilibrated at room temperature (291 K) and crystals suitable for data collection (growth to a size of about 100 μm in all directions) generally appeared overnight. Glycerol (30% (v/v)) added to the reservoir solution sufficed as a cryoprotectant for flash cooling the crystals in liquid nitrogen. A native data set (Supplementary Table I) was collected at beam line 14.1 (BESSY, Berlin), reaching a resolution of 1.9 Å. This and subsequent data sets collected were indexed and integrated using MOSFLM (Leslie, 1992), followed by scaling, merging and conversion of the collected intensities into structure factors using the CCP4 programs SCALA and TRUNCATE (CCP4, 1994). The crystals were monoclinic, with unit cell dimensions of a=69.7Å, b=49.5Å, c=104.4Å and β=106.1°, belonging to space group P21. The solvent content was estimated to be around 54%, with a Matthew coefficient of 2.7, assuming two molecules in the asymmetric unit. The two molecules in the asymmetric unit are related by a pseudo-translational vector (0.5, 0.45, 0.5).

Structure determination and refinement

The first attempt to solve the crystal structure of AfAlkA by molecular replacement, using the previously determined crystal structure of EcAlkA as a search model, failed. AfAlkA and EcAlkA show about 20% sequence identity at the amino-acid level, which is at the lower limit of what is sufficient for this purpose. Although a molecular replacement solution, which was well separated above the next solution, could be identified, all attempts to manually adjust and refine the search model failed. In a second attempt to solve the crystal structure of AfAlkA, heavy atom incorporation techniques were employed. As previous studies have shown that AfAlkA is inhibited by the addition of small amounts of p-hydroxymercuribenzoate (Birkeland et al, 2002), this compound was considered suitable for soaking experiments. After a 1-h soak of 1 mM p-hydroxymercuribenzoic acid solubilized in the crystallization buffer, a crystal was rapidly transferred into the cryo-solution and flash-cooled as described above. Following a XANES (X-ray absorption near edge structure) scan, diffraction data were collected close to the peak of the mercury absorption edge (Hg LIII-edge; λ=1.009 Å) at the tunable macromolecular crystallography beam line ID14-4 (ESRF, Grenoble). This data set was collected to high redundancy (Supplementary Table I) and allowed the solution of the crystal structure of AfAlkA in a SAD approach. Anomalous Patterson plots within the peak data set using the BrukerNonius program XPREP gave a clear indication of heavy atoms being present and ordered in the crystal. Two heavy atom sites, whose cross-vectors resolved the anomalous Patterson, were identified by SHELXD (Schneider and Sheldrick, 2002) using the anomalous differences (FAs from XPREP). The two sites were used as input to SHARP, which was run at 2.5 Å resolution (La Fortelle and Bricogne, 1997). Following solvent flattening and phase extension using DM (CCP4, 1994; Cowtan, 1994), an interpretable electron density map to 1.8 Å resolution was produced. These phases were subsequently fed into ARP/wARP (Perrakis et al, 1999), which built 573 out of the total 590 residues of the two protein monomers in each asymmetric unit. Five hundred and sixty-nine residues were correctly assigned to sequence by ARP/wARP. After a manual rebuilding round using O (Jones et al, 1991), the initial model was refined in REFMAC5 (Winn et al, 2001). Subsequent cycles of refinement interspersed with manual rebuilding resulted in Rwork and Rfree of 18.5 and 22.3%, respectively, with acceptable geometrical parameters. For an overview of the statistics from phasing and refinement, see Supplementary Table I. The native structure of AfAlkA was determined by molecular replacement using the coordinates of the mercury-complexed AfAlkA as a search model in MOLREP (CCP4, 1994). This was followed by rigid body refinement and restrained positional and B-factor refinement in REFMAC5. Cycles of manual rebuilding and refinement reduced the final Rwork and Rfree to 18.1 and 23.9%, respectively. Atomic coordinates and structure factor data have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 2JHJ and 2JHN for the native and mercury-soaked data sets, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Pål Falnes and Magnar Bjørås for purified EcAlkB and hMPG proteins, respectively. We are indebted to Karen Molde and Helene Robstad for technical assistance. The Norwegian Structural Biology Centre (NorStruct) is supported by a grant from the National Program in Functional Genomics (FUGE) with the Research Council of Norway. Provision of synchrotron beamtime at the ESRF and at BESSY is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Aas PA, Otterlei M, Falnes PØ, Vågbø CB, Skorpen F, Akbari M, Sundheim O, Bjørås M, Slupphaug G, Seeberg E, Krokan HE (2003) Human and bacterial oxidative demethylases repair alkylation damage in both RNA and DNA. Nature 421: 859–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abner CW, Lau AY, Ellenberger T, Bloom LB (2001) Base excision and DNA binding activities of human alkyladenine DNA glycosylase are sensitive to the base paired with a lesion. J Biol Chem 276: 13379–13387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alseth I, Osman F, Korvald H, Tsaneva I, Whitby MC, Seeberg E, Bjørås M (2005) Biochemical characterization and DNA repair pathway interactions of Mag1-mediated base excision repair in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 1123–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrows LR, Magee PN (1982) Nonenzymatic methylation of DNA by S-adenosylmethionine in vitro. Carcinogenesis 3: 349–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beranek DT (1990) Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutat Res 231: 11–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland N-K, Ånensen H, Knævelsrud I, Kristoffersen W, Bjørås M, Robb FT, Klungland A, Bjelland S (2002) Methylpurine DNA glycosylase of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Biochemistry 41: 12697–12705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland S, Seeberg E (1996) Different efficiencies of the Tag and AlkA DNA glycosylases from Escherichia coli in the removal of 3-methyladenine from single-stranded DNA. FEBS Lett 397: 127–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner SD, Norman DP, Verdine GL (2000) Structural basis for recognition and repair of the endogenous mutagen 8-oxoguanine in DNA. Nature 403: 859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D50: 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K (1994) DM: an automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography 31: 34–38 [Google Scholar]

- Delaney JC, Essigmann JM (2004) Mutagenesis, genotoxicity, and repair of 1-methyladenine, 3-alkylcytosines, 1-methylguanine, and 3-methylthymine in alkB Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14051–14056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney JC, Smeester L, Wong C, Frick LE, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Drennan CL, Samson LD, Essigmann JM (2005) AlkB reverses etheno DNA lesions caused by lipid oxidation in vitro and in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 855–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan T, Trewick SC, Koivisto P, Bates PA, Lindahl T, Sedgwick B (2002) Reversal of DNA alkylation damage by two human dioxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 16660–16665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M, Wilson GG, Kuo KC, Gehrke CW (1987) N4-methylcytosine as a minor base in bacterial DNA. J Bacteriol 169: 939–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichman BF, O'Rourke EJ, Radicella JP, Ellenberger T (2003) Crystal structures of 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase MagIII and the recognition of alkylated bases. EMBO J 22: 4898–4909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falnes PØ, Johansen RF, Seeberg E (2002) AlkB-mediated oxidative demethylation reverses DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Nature 419: 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T (2006) DNA Repair and Mutagenesis, 2nd edn., Washington, DC: ASM Press [Google Scholar]

- Harding MM (2006) Small revisions to predicted distances around metal sites in proteins. Acta Cryst D 62: 678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis T, Ichikawa Y, Ellenberger T (2000) DNA bending and a flip-out mechanism for base excision by the helix–hairpin–helix DNA glycosylase, Escherichia coli AlkA. EMBO J 19: 758–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C (1993) Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J Mol Biol 233: 123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M (1991) Improved methods for binding protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A 47: 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk H-P, Clayton RA, Tomb J-F, White O, Nelson KE, Ketchum KA, Dodson RJ, Gwinn M, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Richardson DL, Kerlavage AR, Graham DE, Kyrpides NC, Fleischmann RD, Quackenbush J, Lee NH, Sutton GG, Gill S, Kirkness EF, Dougherty BA, McKenney K, Adams MD, Loftus B, Peterson S, Reich CI, McNeil LK, Badger JH, Glodek A, Zhou L, Overbeek R, Gocayne JD, Weidman JF, McDonald L, Utterback T, Cotton MD, Spriggs T, Artiach P, Kaine BP, Sykes SM, Sadow PW, D'Andrea KP, Bowman C, Fujii C, Garland SA, Mason TM, Olsen GJ, Fraser CM, Smith HO, Woese CR, Venter JC (1997) The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature 390: 364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Fortelle ED, Bricogne G (1997) Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. Methods Enzymol 276: 472–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labahn J, Schärer OD, Long A, Ezaz-Nikpay K, Verdine GL, Ellenberger TE (1996) Structural basis for the excision repair of alkylation-damaged DNA. Cell 86: 321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AY, Schärer OD, Samson L, Verdine GL, Ellenberger T (1998) Crystal structure of a human alkylbase-DNA repair enzyme complexed to DNA: mechanisms for nucleotide flipping and base excision. Cell 95: 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie AGW (1992) Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACMB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography No. 26 [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield C, Kerins SM, McCarthy TV (2003) Characterisation of Archaeoglobus fulgidus AlkA hypoxanthine DNA glycosylase activity. FEBS Lett 540: 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien PJ, Ellenberger T (2004) The Escherichia coli 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase AlkA has a remarkably versatile active site. J Biol Chem 279: 26876–26884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TR (1993) Purification and characterization of human 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res 21: 5561–5569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill RJ, Vorob'eva OV, Shahbakhti H, Zmuda E, Bhagwat AS, Baldwin GS (2003) Mismatch uracil glycosylase from Escherichia coli: a general mismatch or a specific DNA glycosylase? J Biol Chem 278: 20526–20532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol 6: 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringvoll J, Nordstrand LM, Vågbø CB, Talstad V, Reite K, Aas PA, Lauritzen KH, Liabakk NB, Bjørk A, Doughty RW, Falnes PØ, Krokan HE, Klungland A (2006) Repair deficient mice reveal mABH2 as the primary oxidative demethylase for repairing 1meA and 3meC lesions in DNA. EMBO J 25: 2189–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydberg B, Lindahl T (1982) Nonenzymatic methylation of DNA by the intracellular methyl group donor S-adenosyl-L-methionine is a potentially mutagenic reaction. EMBO J 1: 211–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM (2002) Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D 58: 1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick B (2004) Repairing DNA-methylation damage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 148–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speina E, Kierzek AM, Tudek B (2003) Chemical rearrangement and repair pathways of 1,N6-ethenoadenine. Mutat Res 531: 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trewick SC, Henshaw TF, Hausinger RP, Lindahl T, Sedgwick B (2002) Oxidative demethylation by Escherichia coli AlkB directly reverts DNA base damage. Nature 419: 174–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyushin BF, Tkacheva SG, Belozersky AN (1970) Rare bases in animal DNA. Nature 225: 948–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN (2001) Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr D 57: 122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata Y, Kato M, Odawara K, Tokuno Y, Nakashima Y, Matsushima N, Yasumura K, Tomita K, Ihara K, Fujii Y, Nakabeppu Y, Sekiguchi M, Fujii S (1996) Three-dimensional structure of a DNA repair enzyme, 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase II, from Escherichia coli. Cell 86: 311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information