Abstract

BACKGROUND

Organizational leaders and scholars have issued calls for the medical profession to refocus its efforts on fulfilling the core tenets of professionalism. A key element of professionalism is participation in community affairs.

OBJECTIVE

To measure physician voting rates as an indicator of civic participation.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional survey of a subgroup of physicians from a nationally representative household survey of civilian, noninstitutionalized adult citizens.

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 350,870 participants in the Current Population Survey (CPS) November Voter Supplement from 1996–2002, including 1,274 physicians and 1,886 lawyers; 414,989 participants in the CPS survey from 1976–1982, including 2,033 health professionals.

MEASUREMENTS

Multivariate logistic regression models were used to compare adjusted physician voting rates in the 1996–2002 congressional and presidential elections with those of lawyers and the general population and to compare voting rates of health professionals in 1996–2002 with those in 1976–1992.

RESULTS

After multivariate adjustment for characteristics known to be associated with voting rates, physicians were less likely to vote than the general population in 1998 (odds ratio 0.76; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.59–0.99), 2000 (odds ratio 0.64; 95% CI 0.44–0.93), and 2002 (odds ratio 0.62; 95% CI 0.48–0.80) but not 1996 (odds ratio 0.83; 95% CI 0.59–1.17). Lawyers voted at higher rates than the general population and doctors in all four elections (P < .001). The pooled adjusted odds ratio for physician voting across the four elections was 0.70 (CI 0.61–0.81). No substantial changes in voting rates for health professionals were observed between 1976–1982 and 1996–2002.

CONCLUSIONS

Physicians have lower adjusted voting rates than lawyers and the general population, suggesting reduced civic participation.

KEY WORDS: professionalism, social science, community health, health policy

INTRODUCTION

Voting is the most basic expression of civic participation and community engagement in a democratic society. Many scholars have argued that doctors’ professional standing elevates expectations for their civic participation. Recent trends including declining trust in medicine and increasing investor–ownership in the health care industry have renewed discussions about medical professionalism and its basic tenets, including duty to engage in advocacy and community affairs.1–5

Medical organizations themselves have issued a series of proclamations and calls for a renewal of medical professionalism. In 2001, the American Medical Association issued its “Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine’s Social Contract with Humanity,” which included a commitment to “advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”6 Their “Principles of Medical Ethics” include the statement that “a physician shall recognize a responsibility to participate in activities contributing to the improvement of the community...”7 More recently, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in conjunction with its European counterpart published the “Charter on Medical Professionalism” with similar views.8

However, few studies have been conducted to assess physicians’ civic behaviors and whether they meet these goals put forth by professional associations. Voting rates offer an imperfect but informative view of the civic behaviors of populations. Voters are more likely to be interested in politics, to give to charity, to volunteer, to serve on juries, to attend community school board meetings, to participate in public demonstrations, and cooperate with their fellow citizens on community affairs.9–12 The act of voting itself has been shown to have spillover effects on other civic behaviors in a relationship that appears causative in nature.12 Conversely, low voting rates are suggestive of a general disengagement from civic life. This study aims to measure the voter participation rates of U.S. physicians as an indicator of civic participation, compare these rates to the general public and another prominent profession, and to ascertain whether participation rates have changed in recent history.

METHODS

We studied the voter participation rates of U.S. physicians compared to lawyers and the general population in congressional and presidential elections between 1996 and 2002. We used the U.S. Bureau of Census Current Population Survey (CPS) November Voter Supplement.13 The CPS is a monthly, nationally representative household survey primarily designed to measure labor force participation. The November Voter Supplement is administered in even-numbered years in the weeks after election day and ascertains whether individuals voted in the most recent election. Specifically, survey respondents are asked: “In any election some people are not able to vote because they are sick or busy or have some other reason, and others do not want to vote. Did you vote in the election held on Tuesday, November X?” Between 1996 and 2002, each November Voter Supplement included approximately 85,000 U.S. adult citizens, including 1,274 physicians and 1,886 lawyers for the entire period.

In addition, we compared the voting rates in the 1996 to 2002 sample with voting rates in the elections between 1976 and 1982 (1976, 1978, 1980, and 1982), the earliest collection of adequate occupational data in the CPS. Because the occupational categories in the data collections between 1976 and 1982 collapsed physicians with other health professionals (i.e., podiatrists, optometrists, dentists, and veterinarians), we created the same category of health professionals in the 1996 to 2002 data for comparison. Physicians represent approximately two thirds of this category in the 1996 to 2002 sample. From 1976 to 1982, the CPS sample ranges from 87,000 to 119,000 U.S. adult citizens and includes 2,033 health professionals over the period.

The CPS response rate typically exceeds 85% in each monthly survey and is more than 90% if unoccupied houses are excluded from the sample frame. Further details and documentation for the CPS are available from the U.S. Census Bureau.14

The primary outcome of odds of physicians voting relative to lawyers and the general population was estimated with multivariate logistic regression models adjusting for a variety of demographic characteristics known to be associated with voter participation rates (age, sex, race, ethnicity, income, education, geography, marital status, employment, duration of residence, home ownership, and the presence of children in the household).15 The odds of voting was estimated for each year of analysis and was subsequently pooled across the years 1996–2002 and the historic reference period 1976–1982 with the inclusion of fixed year effects. We also calculated adjusted probabilities of voting for the same occupational categories (physicians, lawyers, and general population) utilizing the mean values of each covariate. We were not primarily interested in unadjusted voting rates given the known strong correlations of socioeconomic status and voting and the marked demographic differences between physicians and the general population. Survey respondents answering the voter participation question with “no,” “do not know,” or those who did not respond to the question were classified as nonvoters. This approach is consistent with the methods of the U.S. Census Bureau.15 In separate models, nonrespondents and those answering “do not know” were classified as missing and dropped from the analysis. Statistical significance was prespecified with a two-tailed test below the 0.05 level. The statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 9 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex, USA).

This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Survey respondents from the principal period of analysis, 1996–2002, included 1,274 physicians, 1,886 lawyers, and 347,710 other individuals that were neither physicians nor lawyers. The characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 1. As expected, physicians and lawyers differ from the general population along most demographic variables.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants by Occupation

| Doctors, N = 1,274 (%) | Lawyers, N = 1,886 (%) | Other, N = 347,710 (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 45.0 | 44.1 | 46.2 | 0.015* |

| <0.001† | ||||

| Female | 26.3 | 30.8 | 53.1 | <0.001 |

| Married | 79.0 | 70.6 | 58.7 | <0.001 |

| Nonrural residence | 87.3 | 89.3 | 74.6 | <0.001 |

| Children in household | 52.3 | 48.3 | 41.4 | <0.001 |

| Employed | 99.5 | 98.5 | 64.5 | <0.001 |

| Race and Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| White | 80.5 | 90.4 | 80.8 | |

| African-American | 4.6 | 4.2 | 9.7 | |

| Native American | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.2 | |

| Asian-American | 10.8 | 2.3 | 2.6 | |

| Hispanic | 3.8 | 2.7 | 5.8 | |

| Region | <0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 26.6 | 26.4 | 21.3 | |

| Midwest | 23.1 | 20.7 | 24.8 | |

| South | 29.0 | 30.2 | 30.6 | |

| West | 21.3 | 22.8 | 23.3 | |

| Income | <0.001 | |||

| <$20,000 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 18.3 | |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 18.6 | |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 4.3 | 5.9 | 14.8 | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 7.1 | 13.0 | 16.8 | |

| >$75,000 | 75.0 | 66.3 | 17.1 | |

| Duration of Residence | <0.001 | |||

| <1 Year | 15.9 | 12.8 | 14.6 | |

| 1–5 Years | 31.7 | 34.2 | 28.0 | |

| >5 Years | 52.4 | 53.0 | 57.5 | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| High school or less | 0.0 | 0.0 | 48.8 | |

| Some college | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28.2 | |

| Bachelors degree | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.1 | |

| Graduate degree | 100.0 | 100.0 | 7.0 |

*Doctors compared to nondoctors and nonlawyers (other)

†Lawyers compared to nondoctors and nonlawyers (other)

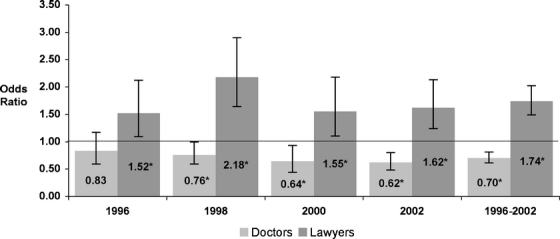

After multivariate adjustment, physicians were significantly less likely to vote than the general population in 3 of the 4 studied elections as shown by odds ratios in Figure 1. In these same 4 elections, lawyers voted at much higher rates than the general population (Fig. 1). In all years, lawyers’ voting rates were significantly higher than those of doctors (P < .001). After pooling data across the four elections (1996–2002) and including fixed year effects, physicians were less likely to vote than the general population (odds ratio 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.61–0.81; P < .001) and lawyers were more likely to vote than the general population (odds ratio 1.74; 95% CI 1.49–2.02; P < .001). Results were similar (although confidence intervals widened) in analyses excluding item nonresponders and individuals answering “do not know” to the voting question.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds of voting of physicians and lawyers compared to the general population from 1996 to 2002. P values for physicians compared to the general population: 1996, P = .3; 1998, P = .045; 2000, P = .018; 2002, P < .001; and 1996–2002, P < .001. P values for lawyers compared to the general population: 1996, P = .015; 1998, P < .001; 2000, P = .012; 2002, P < .001; and 1996–2002, P < .001. Statistical significance is denoted in the figure with an asterisk for P < .05.

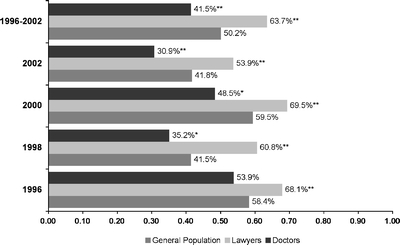

Figure 2 depicts the adjusted probability of voting across the 4 elections (1996–2002) for doctors and lawyers compared to the general population. In a pooled analysis of the 4 elections, doctors’ adjusted voting rates were 8.7 percentage points lower than the general population (41.5 vs 50.2%; 95% CI for difference 5.2–12.2 percentage points; P < .001) and lawyers’ adjusted voting rates were 13.5 percentage points higher than the general population (63.7 vs 50.2%; 95% CI for difference 10.0–17.0 percentage points; P < .001). The adjusted difference between doctors and lawyers was 22.2 percentage points (P < .001).

Figure 2.

Adjusted probability of voting of physicians compared to lawyers and the general population from 1996 to 2002. P values are calculated for physicians and lawyers compared to the general population. Statistical significance is denoted with an asterisk for P < .05 and double asterisks for P < .01.

Adjusted voting rates for health professionals in the periods 1976–1982 and 1996–2002 were calculated. No substantial change in voting rates of the broader category of health professionals was observed between the periods 1976–1982 (odds ratio 0.77; 95% CI 0.68–0.86) and 1996–2002 (odds ratio 0.75, 95% CI 0.67–0.85). In the period 1996–2002, this occupational category is 66% physicians. Although this proportion may have changed over the period, there is no evidence of a substantial change in voting participation over time.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze the voting rates of physicians in the United States and finds that physicians vote less often than the general population and less often than lawyers, when controlling for a variety of socioeconomic characteristics. Moreover, our research suggests that the low voter participation rates of doctors may date back to at least the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Our research studying the electoral participation of physicians is not motivated by a desire to simply measure political influence. The entire physician population, totaling just more than 800,000, represents a rather small voting bloc in the United States.16 Only in highly contested elections with small victory margins and unified physician views could physicians possibly tip the balance in favor of a particular candidate. However, the participation of physicians in elections remains important for a variety of reasons. Most significantly, it represents a basic and simple act of participating in community and public affairs, a role that many scholars and medical professional associations have described as an essential responsibility of the medical profession. Although medical professionalism is hard to define, many agree with the notion that civic engagement is an important aspect of professionalism.2–6,8,17

Although an individual physician’s failure to vote would not be described as unprofessional behavior, lower voting rates evident in the collective behavior of physicians may signal civic disengagement. Robert Putnam9 has equated electoral abstention to a fever “even more important as a sign of deeper trouble in the body politic than as a malady itself” and that “declining electoral participation is merely the visible symptom of a broader disengagement from community life.”

Society has expectations of the professions extending beyond an assurance of competence; it relies on the professions as an important ethical voice and participant in public life.18,19 Our finding of low voter participation of doctors raises concerns about that voice and questions the current role of physicians in public affairs and community life.

Why do doctors vote less than their socioeconomic position would predict?15 Whereas our data source does not permit exploration of potential causes of low voting rates, we offer some hypotheses. A study of professional associations’ agendas over the 20th century, measured by the content of their presidential speeches, reveals a trend toward declining discussions of the sociocultural purpose of the professions and increasing emphasis on internal affairs and professional achievement.20 Perhaps physicians became increasingly focused on professional accomplishment as medicine shifted toward greater specialization. Another factor may have been the challenge posed to earlier conceptions of physician authority by the growing influence of payers and regulation. These trends might have led physicians to perceive a diminished role for themselves in public affairs.17,21 We did not find evidence of changing voting rates between 1976–1982 and 1996–2002, which would have lent further support to these hypotheses; however, the first major shift toward specialization and the precipitous decline in physicians authority preceded our earliest data.19,22,23

In contrast, physicians may also view their clinical work as having great social purpose. As a result, civic participation might appear less important. Voting in particular may be viewed as trivial relative to the significance of physicians’ daily clinical encounters. Perhaps satisfaction with the social importance of one’s primary professional activities coupled with substantial time pressures in busy clinical practices substitutes for more basic and individually ceremonial aspects of civic life. Medical schools may also play a role by selecting individuals for admission that are less inclined toward civic participation and more focused on the science of medicine. Medical training may also lead physicians to perceive voting as a political act that is somehow in conflict with professional duties and patient care. Lawyers offer an interesting comparison group because law schools are likely to attract students with predispositions toward civics and government and also foster these interests as part of the formal curriculum.

Many commentaries on medical professionalism focus attention on civic engagement as an important element; however, empirical research seeking to evaluate physician attitudes and behaviors focuses strongly on day-to-day patient care experiences and possible violations of basic ethical standards. Most studies also focus exclusively on the medical training environment and tend to neglect physicians in practice.24,25 Future research should overcome these limitations in the literature, by describing the civic behaviors of the medical profession to determine if physicians are disengaged from community life as their voting rates suggest, and determining what attitudes might underlie such disengagement if it exists. Some specific activities that can be explored include service on nonprofit boards, philanthropy, volunteering with community organizations, and more widespread forms of political participation. In the meantime, we believe the medical profession can begin to take modest steps to encourage civic participation by promoting the principles of the Charter on Medical Professionalism,8 encouraging voter participation and modeling and celebrating civic engagement in medical schools and residency training programs.

Civic engagement is an important social good, and physicians’ status, education, and resources enhance their ability to contribute individually and collectively. With trust in the medical profession eroding, improved civic engagement might improve medicine’s relationship with society.1,18,26 The U.S. health care system is widely recognized as plagued with major problems, including the intractable number of uninsured and thousands of associated deaths.27 Local communities are afflicted with wide-ranging problems affecting the health of nearly every American. Rothman and O’Toole28 have argued that “a civil society grappling with issues of equity and humaneness, in which health care is one of the most central concerns, desperately needs physician input and physician participation.” As members of a profession, physicians should be participating in public affairs and contributing solutions.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Rothman, PhD, of Columbia University for providing comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript and Mark Lopez, PhD, of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at the University of Maryland for contributing to the initial study design. David Grande conducted this research as a Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania and presented it at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Los Angeles, Calif on April 29, 2006.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest None disclosed

References

- 1.Schlesinger M. A loss of faith: the sources of reduced political legitimacy for the American medical profession. Milbank Q. 2002;80:185–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Swick HM. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75:612–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Johnston SE. Professionalism: an ideal to be sustained. Lancet. 2000;356:156–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Rothman DJ. Medical professionalism: focusing on the real issues. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1284–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gruen RL, Pearson SD, Brennan TA. Physician-citizens—public roles and professional obligations. JAMA. 2004;291:94–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.American Medical Association. Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine’s Social Contract with Humanity. 2001. Retrieved February 6, 2006 from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/upload/mm/369/decofprofessional.pdf. [PubMed]

- 7.American Medical Association. AMA Principles of Medical Ethics. 2001. Retrieved February 6, 2006 from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2512.html.

- 8.ABIM Foundation, ACD-ASIM Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: the Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2000.

- 10.Conway MM. Political Participation in the United States (2nd edition). Washington, DC: CQ Press; 1991.

- 11.Knack S, Kropf ME. For shame! The effect of community cooperative context on the probability of voting. Polit Psychol. 1998;19:585–99. [DOI]

- 12.McCann JA. Electoral participation and local community activism: spillover effects, 1991–1996. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston, Mass, September, 1998.

- 13.U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Current population survey: voter supplement November 1976, 1978, 1980, 1982, 1996, 1998, 2000, & 2002 (computer file). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce. Ann Arbor, Mich: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (distributor).

- 14.Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce Census Bureau; n.d. Retrieved January 27, 2006 from http://www.census.gov/cps/.

- 15.Day JC, Holder K. Voting and registration in the election of November 2002. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; 2004.

- 16.Goodman D. Twenty-year trends in regional variations in the U.S. physician workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;Suppl Web Exclusive:VAR90–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wynia MK, Latham SR, Kao AC, Berg JW, Emanuel LL. Medical professionalism in society. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1612–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sullivan WM. Medicine under threat: professionalism and professional identity. CMAJ. 2000;162:673–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1982.

- 20.Brint S, Levy CS. Professions and civic engagement. In: Skocpol T, Fiorina MP, eds. Civic Engagement in American Democracy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 1999:163–210.

- 21.Krause EA. Death of the Guilds: Professions, States and the Advances of Capitalism, 1930 to the Present. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 1996.

- 22.Donini-Lenhoff FG, Hedrick HL. Growth of specialization in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2000;284:1284–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Green LA, Dodoo MS, Ruddy G, et al. The Physician Workforce of the United States: a Family Medicine Perspective. Washington, DC: American Academy of Family Physicians Robert Graham Center; 2004.

- 24.Arnold L. Assessing professional behavior: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77:502–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Stern D, Lingard L. The anatomy of the professional lapse: bridging the gap between traditional frameworks and students’ perceptions. Acad Med. 2002;77:516–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Stevens RA. Public roles for the medical profession in the United States: beyond theories of decline and fall. Milbank Q. 2001;79:327–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002.

- 28.Rothman DJ, O’Toole T. Physicians and the body politic: ideas for an Open Society (occasional papers from OSI-US Programs). 2002;2:2–5.