Abstract

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a newly identified serine/threonine protein kinase implicated in integrin signaling. To investigate the functions of ILK in vivo, we have analyzed the expression and regulation of ILK in the skin, in which proper control of cell-extracellular matrix interactions and cell proliferation is essential for its normal development and homeostasis. We report here that ILK is abundantly expressed throughout the extracellular matrix-rich dermis. ILK mRNA was also detected in the hair follicles and the basal cells of the interfollicular epidermis. However, ILK expression is lost in the suprabasal layers of keratinocytes that are undergoing terminal differentiation. PINCH, an ILK-binding protein, exhibited a similar expression pattern in the skin. Recent studies have indicated that erbB-2, a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family, plays a pivotal role in epidermal growth, differentiation, and hair follicle morphogenesis. Using a transgenic mouse system in which an activated erbB-2 is overexpressed in the epidermis, we show that ILK expression is regulated by erbB-2. The in vivo expression and regulation patterns of ILK, together with its biochemical activities, suggest an important role of ILK in coordinating the integrin signaling pathways and the growth factor signaling pathways in the development of the skin and the pathogenesis of skin diseases.

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a newly identified serine/threonine protein kinase that has been implicated in cellular control of cell-extracellular matrix interactions and cell proliferation. 1-3 ILK regulates integrin-mediated cell adhesion, E-cadherin expression, and extracellular fibronectin matrix assembly. 1,3 Moreover, overexpression of ILK in rat epithelial cells induces anchorage-independent cell growth in culture 1 and tumor formation in vivo. 3 Biochemical and cell biological analyses have shown that ILK is intimately involved in the cell adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression by regulating the level and/or activity of several key components of cell cycle machinery, including cyclin A, cyclin D1, and cyclin-dependent kinases. 2 In addition to binding to integrins, we recently have found that ILK interacts with PINCH (Y Tu, F Li, S Goicoechea, C Wu, manuscript submitted for publication), an intracellular adaptor protein comprising primarily five LIM domains. 4 The ILK gene has been mapped to the human chromosome 11p15.5 to p15.4 region 5 and a conserved region in mouse chromosome 7, 6 which includes a syntenic group of genes encoding Harvey-ras, insulin-like growth factor II, and target of antiproliferative antibody 1. It is particularly interesting to note that several breakpoints associated with the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, a genetic disorder with overgrowth and predisposition to Wilms’ tumor, are located in the same area within the human chromosome 11p15.5 region. 7

Although the biochemical, cell biological, and genetic evidence has implicated important roles of ILK in the pathogenesis of tumor and other hyperproliferative diseases, the in vivo expression and regulation of ILK were previously not known. Previous studies have shown that members of the epidermal growth factor receptor family play critical roles in cell differentiation and proliferation in the skin. 8-13 For example, overexpression of a constitutively active form of erbB-2, a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family, 14,15 in the hair follicles and the basal cells of the epidermis resulted in profound epidermal, dermal, and hair follicle abnormalities, including epidermal hyperplasia, preneoplasia, papilloma, hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, and dermal hyperplasia. 13 The majority of the hair follicles were replaced by bizarre hyperproliferative intradermal squamous invaginations, whereas the rest of the follicles exhibited severe hyperplasia and disorganization. 13 It becomes clear now that the growth factor signaling pathways coordinate with the integrin signaling pathways in control of cell proliferation and differentiation. 16-19 To investigate the functions of ILK in vivo, we have analyzed the expression of ILK in normal mouse skins and those of the erbB-2-transgenic mice. We report here that ILK is expressed by the dermal fibroblasts, the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicles, and the basal cells of the epidermis in normal mouse skins. The ILK expression is lost in the differentiating and postmitotic suprabasal keratinocytes. Strikingly, overexpression of the activated erbB-2 dramatically and specifically increased ILK expression along the basal layers of the hyperplastic epidermis, the squamous invaginations, and the outer root sheath-equivalent compartment of the hyperplastic follicles. These results provide important in vivo evidence suggesting a role of ILK in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation in the skin.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Normal mice (B6 × SJL) were obtained from the animal facility of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The K14-erbB-2 transgenic mice were generated by injection of one-cell B6 × SJL mouse zygotes with a K14-erbB-2 transgene in which the cDNA encoding an activated form of rat c-neu/erbB-2 (with Val664 to Glu664 mutation) 20,21 was placed downstream of the 2.3-kb promoter for the human K14 gene. 13 All mice were handled in the University of Alabama at Birmingham animal facility in accordance with the institutional animal care policies.

In Situ Hybridization

Frozen sections (10 μm) of the back skins from normal neonatal (1-day-old) B6 × SJL mice and the K14-erbB-2 transgenic mice were subjected to in situ hybridization using 35S-labeled anti-sense riboprobes that correspond to the full-length mouse ILK cDNA (1.4 kb), 6 human PINCH cDNA (0.9 kb), 4 and the C-terminal fragment of the rat erbB-2 cDNA (2.7-kb NdeI-SalI fragment), 13 respectively. High-specific activity riboprobes were synthesized in 10-μl reactions containing 100 μCi [35S]UTP and 100 μCi [35S]CTP (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), 10 mmol/L NaCl, 6 mmol/L MgCl2, 40 mmol/L Tris (ph 7.5), 2 mmol/L spermidine, 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 500 μmol/L each of unlabeled ATP and GTP, 25 μmol/L each of unlabeled UTP and CTP, 0.5–1 μg linearized template, 15 U of the appropriate polymerase, and 15 U RNase inhibitor (RNasin, Promega, Madison, WI). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 42°C for 60 minutes. Labeled cRNA probes were purified with Bio-Spin 6 columns (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). The skin sections were hybridized with the probes at 55°C temperature for 15 to 18 hours. 13 After hybridization, emulsion dip (NTB2 nuclear emulsion, Kodak, Rochester, NY), exposure, and developing, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin and subjected to microscopic examination under bright-field and dark-field illumination. In control experiments, serial sections of the back skins from both the normal and K14-erbB-2 transgenic mice were hybridized with 35S-labeled cRNA probes for hexaminidase A and O-linked N-acetyl glucosamine transferase, respectively. The results showed that hexaminidase A and O-linked N-acetyl glucosamine transferase were expressed by both epidermal and dermal cells. Moreover, in contrast to ILK expression, which was markedly increased in the K14-erbB-2 transgenic mouse skins (see Results), neither the expression of hexaminidase A nor that of O-linked N-acetyl glucosamine transferase was altered by the overexpression of the activated erbB-2.

Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) Immunostaining

Paraffin sections of the erbB-2-transgenic and control mouse back skins were stained with a mouse monoclonal anti-PCNA antibody (1:100 dilution, BioGenex, San Ramon, CA). After washing, the bound anti-PCNA antibody was detected with a biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The immune complexes were visualized with a Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride as chromogen. The sections were slightly counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories).

Results

Expression of ILK in Normal Mouse Skins

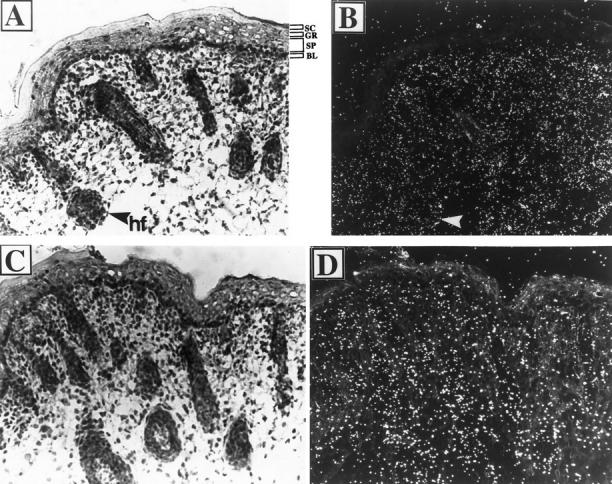

We analyzed the expression of ILK in mouse skins by in situ hybridization. The skin sections from the back of a 1-day-old normal B6 × SJL mouse were hybridized with a 35S-labeled antisense cRNA probe of ILK. Abundant ILK mRNA was detected in the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicles and in the dermal fibroblasts (Figure 1, A ▶ (bright field) and B (dark field)). Additionally, ILK mRNA was present, although at a relatively lower level, in the basal cells of the interfollicular epidermis. In contrast, no appreciable ILK expression was detected in the spinous and granular layers or in the stratum corneum.

Figure 1.

In situ localization of ILK and PINCH mRNAs in normal mouse skins. Frozen sections of the back skin of 1-day-old mouse were subjected to in situ hybridization using [35S]UTP- and [35S]CTP-labeled ILK (A and B) and PINCH (C and D) cRNA probes, respectively. After hybridization, sections were dipped in liquid emulsion and exposed for 1 week before developing. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. The same fields were examined by bright-field (A and C) and dark-field (B and D) microscopy. SC, stratum corneum; GR, granular cells; SP, spinous cells; BL, basal layer; hf, hair follicle. Arrows indicate hair follicles. Original magnification (A to D), ×200.

Expression of the ILK-Binding Protein PINCH in Normal Mouse Skin

We next determined the cellular expression of the ILK-binding protein PINCH in the skin. The skin sections of the neonatal mouse were hybridized with a 35S-labeled antisense cRNA probe of PINCH. The results showed that PINCH mRNA was primarily expressed by the dermal and the outer root sheath cells (Figure 1, C ▶ (bright field) and D (dark field)). No PINCH expression was detected in the suprabasal keratinocytes of the epidermis. Thus, the expression pattern of PINCH mRNA resembles that of ILK, consistent with a role of PINCH in ILK function in vivo.

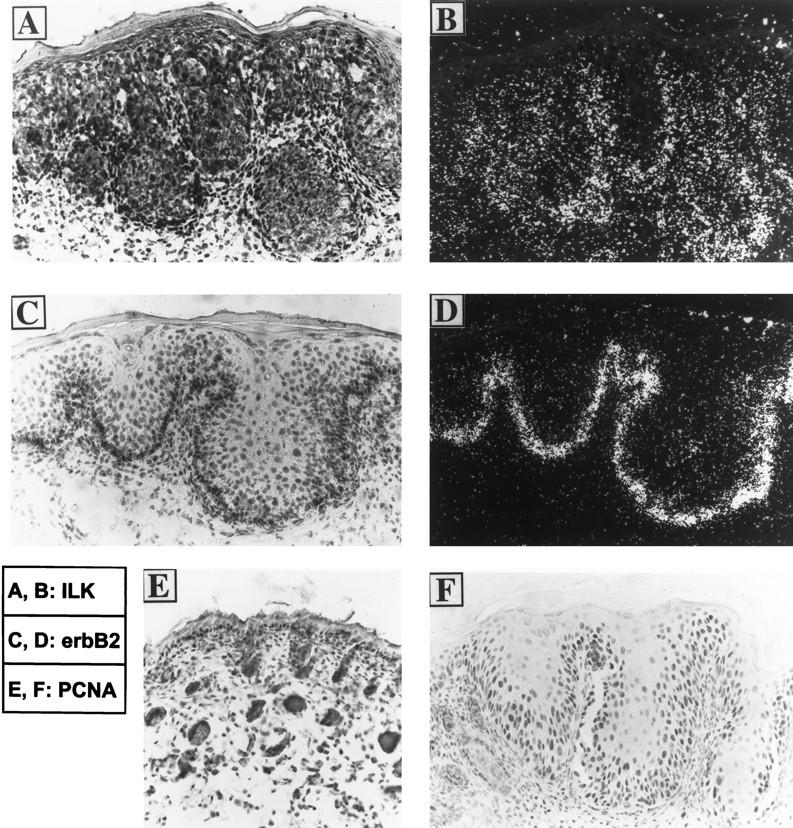

Stimulation of ILK Expression in the Epidermis by Overexpression of erbB-2

To determine whether ILK expression in the skin is altered under pathological conditions, we analyzed the ILK expression in the skins of the K14-erbB-2 transgenic mice. In normal mouse skins, erbB2 is expressed predominantly in the outer root sheath of the hair follicles. 13,22-24 In addition, low levels of erbB-2 transcripts were also present throughout the interfollicular epidermis with relatively higher expression in the basal cells. 13,22-24 The K14 promoter faithfully targets the expression of the transgene (activated erbB-2) to the basal cells and the outer root sheath of the hair follicles, sites to which the endogenous erbB-2 expression has been localized. 13 The K14-erbB-2 transgenic mice exhibited severe epidermal hyperplasia, hyperplastic hair follicle, and numerous hyperproliferative intradermal squamous invaginations that may arise from abnormally developed hair follicles. 13 The back skin sections of neonatal K14-erbB-2 transgenic mice were hybridized with a 35S-labeled ILK cRNA probe (Figure 2, A ▶ (bright field) B (dark field)) or a 35S-labeled erbB-2 cRNA probe (Figure 2, C ▶ (bright field) and D (dark field)) as a control. Abundant erbB-2 mRNA was detected along the basal layers of the hyperplastic epidermis and squamous invaginations of the transgenic skins (Figure 2 ▶ , C and D), consistent with the basal and the outer root sheath specificity of the K14 promoter. 25 Strikingly, ILK expression was significantly and specifically up-regulated in the erbB-2-overexpressing basal-most several layers of the hyperplastic squamous invaginations (Figure 2 ▶ , A and B), whereas the ILK expression in dermal fibroblasts remained unchanged. Therefore, the expression of ILK along the basal layers is distinctively higher than the dermal fibroblasts, which markedly differs from the skin of the normal mouse, in which ILK is equally expressed in the hair follicles and dermal fibroblasts (Figure 1 ▶ , A and B). Staining of the transgenic and control mouse skin sections with an anti-PCNA 26 antibody, a marker of proliferating cells, 27 showed that the cells in which ILK expression was up-regulated by erbB-2 overexpression were highly proliferative (Figure 2F) ▶ .

Figure 2.

In situ localization of ILK mRNA in the skin of the transgenic mouse overexpressing the activated erbB-2. A to D: In situ localization of ILK and erbB-2 mRNAs. Frozen sections of the back skin of a 1-day-old K14-erbB-2 transgenic founder mouse (TG4839) were subjected to in situ hybridization using [35S]UTP- and [35S]CTP-labeled cRNA probes for the ILK (A and B) or the erbB-2 (C and D). After hybridization, sections were dipped in liquid emulsion and exposed for 1 week before developing. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. The same fields were examined by bright-field (A and C) and dark-field (B and D) microscopy. E and F: PCNA immunostaining in neonatal skins of normal (E) and the K14-erbB-2 (F) mice. Paraffin sections were subjected to PCNA immunostaining with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride as the chromogen. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Original magnification (A to F), ×200.

Additionally, we have observed that the expression of PINCH was also increased, although to a much lesser extent than that of the ILK expression, in the areas where the activated erbB-2 was overexpressed (eg, the outer root sheath of the hair follicles; data not shown).

Discussion

The results obtained from this study reveal several important features of ILK expression in the skin. First, ILK expression in normal mouse epidermis is confined to the outer root sheath of hair follicles and the basal keratinocytes of the interfollicular epidermis. The keratinocytes in the suprabasal layers, which are undergoing terminal differentiation and are largely postmitotic, are devoid of ILK. The highly restricted expression pattern of ILK in the epidermis resembles that of the β1 integrins, to which ILK binds. 1 The β1 integrins normally are also confined to the proliferative basal keratinocytes. 28 Watt and Jones have shown that the proliferative potential of the keratinocytes is correlated to the level and the activation state of the cell-surface β1 integrins, 28 and the stem cells can be effectively isolated based on their strong adhesion to fibronectin, type IV collagen, or other extracellular matrix proteins. 29 Moreover, forced expression of functional β1 integrins (eg, α5β1 or α2β1) in the suprabasal epidermal layers of transgenic mice resulted in epidermal hyperproliferation, perturbed keratinocyte differentiation, and other features reminiscent of psoriasis. 30 The similarity between the expression patterns of ILK and the β1 integrins, together with the previous observations that ILK is capable of binding and phosphorylating the β1 integrins 1 and promoting integrin-mediated fibronectin matrix assembly, 3 suggest that ILK likely works in concert with the β1 integrins in regulation of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation.

The second important observation of this study is that ILK expression is regulated by erbB-2, an oncogenic protein, in vivo. ErbB-2 is normally expressed in basal cells of the epidermis and the outer root sheath of the hair follicles. 22-24,31 Overexpressing the constitutively active erbB-2 under the control of human keratin K14 promoter, which directed its expression to cells in which erbB-2 is normally expressed, induced extensive and striking hyperplastic skin phenotypes 13 that share many features that, although more severe, are similar to those observed in the K14-TGFα transgenic mice. 25 All but one of the K14-erbB-2 transgenic mice died before or shortly after birth, probably as a consequence of defects in the skin and esophagus. 13 It has become increasingly clear that the integrin signaling pathways coordinate with the growth factor pathways in regulation of cell proliferation. In fact, the hair follicle and eyelid defects induced by overexpression of the β1 integrins are extremely similar to those induced by mutations in transforming growth factor α 32,33 or epidermal growth factor receptor. 34 Because ILK is involved in integrin signaling and can activate several key components of cell cycle machinery, 2 the increase of ILK expression induced by overexpression of the activated erbB-2 in the epidermis likely contributes to the extensive and striking hyperplastic skin abnormalities, including epidermal hyperplasia, preneoplasia, papilloma, hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, and dermal hyperplasia, observed in the erbB-2 transgenic mice. 13 It will be important to determine in future studies whether overexpression of ILK in the epidermis can induce a phenotype similar to that of the erbB-2 transgenic mice.

Abundant ILK expression in normal mouse skin was detected throughout the dermis, into which extensive extracellular matrices were deposited. Previous studies have shown that integrins not only receive signals from the extracellular matrix but also actively participate in the formation of the extracellular matrix. 35,36 In a recent study, we found that overexpression of ILK in cultured intestinal epithelial cells, which normally assemble littler fibronectin matrix, dramatically stimulated the deposition of fibronectin into the matrix. 3 Thus, loss of ILK expression in the suprabasal layers of the epidermis is likely functionally important for keratinocyte terminal differentiation, as the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes is inhibited in the presence of fibronectin. 37 On the other hand, the high expression level of ILK in the matrix-rich dermis may reflect, among other things, a positive regulatory role of ILK in promoting extracellular matrix deposition in vivo.

In summary, our results provide in vivo evidence supporting a role of ILK in regulation of cell proliferation and cell-matrix interactions in the skin. Future studies should include analyses of ILK expression and regulation in human hyperproliferative and fibrotic skin diseases.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Chuanyue Wu, 217 Volker Hall, Department of Cell Biology and the Cell Adhesion and Matrix Research Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294-0019. E-mail: cwu@cellbio.bhs.uab.edu.

Supported by research grants from American Heart Association (grant 95012830), American Lung Association, and the Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Cell Adhesion and Matrix Research Center of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (all to CW). CW is an Edward Livingston Trudeau Scholar of the American Lung Association and a Parker B. Francis Fellow in Pulmonary Research of the Francis Families Foundation. WX and JEK were supported by United States Public Health Service grants DK48882 and DK43652.

Wen Xie’s present address is Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Gene Expression Laboratory, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037.

References

- 1.Hannigan GE, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Fitz-Gibbon L, Coppolino MG, Radeva G, Filmus J, Bell JC, Dedhar S: Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new β1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature 1996, 379:91-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radeva G, Petrocelli T, Behrend E, Leunghagesteijn C, Filmus J, Slingerland J, Dedhar S: Overexpression of the integrin-linked kinase promotes anchorage-independent cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:13937-13944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu C, Keightley SY, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Radeva G, Coppolino M, Goicoechea S, McDonald JA, Dedhar S: Integrin-linked protein kinase (ILK) regulates fibronectin matrix assembly, E-cadherin expression, and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:528-536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rearden A: A new Lim protein containing an autoepitope homologous to “senescent cell antigen.” Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994, 201:1124-1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannigan GE, Bayani J, Weksberg R, Beatty B, Pandita A, Dedhar S, Squire J: Mapping of the gene encoding the integrin-linked kinase, ILK, to human chromosome 11p15.5–p15.4. Genomics 1997, 42:177-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li F, Liu J, Mayne R, Wu C: Identification and characterization of a mouse protein kinase that is highly homologous to human integrin-linked kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1997, 1358:215-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shows TB, Alders M, Bennett S, Burbee D, Cartwright P, Chandrasekharappa S, Cooper P, Courseaux A, Davis C, Devignes M-D, Deville P, Elliott R, Evans G, Fantes J, Garner H, Gaudray P, Gerhard DS, Gessler M, Higgins M, Hummerich H, James M, Lagercrantz J, Litt M, Little P, Mannens M, Munroe D, Nowak N, O’Brien S, Parker N, Perlin M, Reid L, Richard C, Sawicki M, Swallow D, Thakker R, van Heyningen V, van Schothorst E, Vorechovsky I, Wadelius C, Weber B, Zabel B: Report of the Fifth International Workshop on Human Chromosome 11 Mapping (1996). Cytogenet Cell Genet 1996, 74:1-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miettinen PJ, Berger JE, Meneses J, Phung Y, Pedersen RA, Werb Z, Derynck R: Epithelial immaturity and multiorgan failure in mice lacking epidermal growth factor receptor. Nature 1995, 376:337-341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sibilia M, Wagner EF: Strain-dependent epithelial defects in mice lacking the EGF receptor [published erratum appears in Science 1995, 269: 909]. Science 1995, 269:234-238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Threadgill DW, Dlugosz AA, Hansen LA, Tennenbaum T, Lichti U, Yee D, LaMantia C, Mourton T, Herrup K, Harris RC, Barnard JA, Yuspa SH, Coffey RJ, Magnuson T: Targeted disruption of mouse EGF receptor: effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science 1995, 269:230-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murillas R, Larcher F, Conti CJ, Santos M, Ullrich A, Jorcano JL: Expression of a dominant negative mutant of epidermal growth factor receptor in the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits striking alterations in hair follicle development and skin structure. EMBO J 1995, 14:5216-5223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen LA, Alexander N, Hogan ME, Sundberg JP, Dlugosz A, Threadgill DW, Magnuson T, Yuspa SH: Genetically null mice reveal a central role for epidermal growth factor receptor in the differentiation of the hair follicle and normal hair development. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:1959-1975 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie W, Chow LT, Wu X, Chin E, Paterson AJ, Kudlow JE: Targeted expression of activated erbB-2 to the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits striking developmental abnormalities in the epidermis and hair follicles. Cell Growth Differ 1998, 9:313-325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougall WC, Qian X, Peterson NC, Miller MJ, Samanta A, Greene MI: The neu-oncogene: signal transduction pathways, transformation mechanisms and evolving therapies. Oncogene 1994, 9:2109-2123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carraway KLR, Cantley LC: A neu acquaintance for erbB3 and erbB4: a role for receptor heterodimerization in growth signaling. Cell 1994, 78:5-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks PC, Klemke RL, Schon S, Lewis JM, Schwartz MA, Cheresh DA: Insulin-like growth factor receptor cooperates with integrin αvβ5 to promote tumor cell dissemination in vivo. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:1390-1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Gutkind JS, Yamada KM: Integrins can collaborate with growth factors for phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases and MAP kinase activation: roles of integrin aggregation and occupancy of receptors. J Cell Biol 1996, 135:1633-1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujii K: Ligand activation of overexpressed epidermal growth factor receptor results in loss of epithelial phenotype and impaired RGD-sensitive integrin function in HSC-1 cells. J Invest Dermatol 1996, 107:195-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plopper GE, McNamee HP, Dike LE, Bojanowski K, Ingber DE: Convergence of integrin and growth factor receptor signaling pathways within the focal adhesion complex. Mol Biol Cell 1995, 6:1349-1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bargmann CI, Weinberg RA: Oncogenic activation of the neu-encoded receptor protein by point mutation and deletion. EMBO J 1988, 7:2043-2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bargmann CI, Hung MC, Weinberg RA: Multiple independent activations of the neu oncogene by a point mutation altering the transmembrane domain of p185. Cell 1986, 45:649-657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokai Y, Cohen JA, Drebin JA, Greene MI: Stage- and tissue-specific expression of the neu oncogene in rat development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987, 84:8498-8501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quirke P, Pickles A, Tuzi NL, Mohamdee O, Gullick WJ: Pattern of expression of c-erbB-2 oncoprotein in human fetuses. Br J Cancer 1989, 60:64-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maguire HC, Jr, Jaworsky C, Cohen JA, Hellman M, Weiner DB, Greene MI: Distribution of neu (c-erbB-2) protein in human skin. J Invest Dermatol 1989, 92:786-790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vassar R, Fuchs E: Transgenic mice provide new insights into the role of TGF-α during epidermal development and differentiation. Genes Dev 1991, 5:714-727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bravo R, Frank R, Blundell PA, Macdonald-Bravo H: Cyclin/PCNA is the auxiliary protein of DNA polymerase-delta. Nature 1987, 326:515-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall PA, Levison DA, Woods AL, Yu CC, Kellock DB, Watkins JA, Barnes DM, Gillett CE, Camplejohn R, Dover R, Waseem NH, Lane DP: Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) immunolocalization in paraffin sections: an index of cell proliferation with evidence of deregulated expression in some neoplasms. J Pathol 1990, 162:285-294(see comments) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watt FM, Jones PH: Expression and function of the keratinocyte integrins. Development 1993, (suppl):185-192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones PH, Watt FM: Separation of human epidermal stem cells from transit amplifying cells on the basis of differences in integrin function and expression. Cell 1993, 73:713-724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll JM, Romero MR, Watt FM: Suprabasal integrin expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice results in developmental defects and a phenotype resembling psoriasis. Cell 1995, 83:957-968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Press MF, Cordon-Cardo C, Slamon DJ: Expression of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in normal human adult and fetal tissues. Oncogene 1990, 5:953-962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann GB, Fowler KJ, Gabriel A, Nice EC, Williams RL, Dunn AR: Mice with a null mutation of the TGF α gene have abnormal skin architecture, wavy hair, and curly whiskers and often develop corneal inflammation. Cell 1993, 73:249-261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luetteke NC, Qiu TH, Peiffer RL, Oliver P, Smithies O, Lee DC: TGF α deficiency results in hair follicle and eye abnormalities in targeted and waved-1 mice. Cell 1993, 73:263-278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luetteke NC, Phillips HK, Qiu TH, Copeland NG, Earp HS, Jenkins NA, Lee DC: The mouse waved-2 phenotype results from a point mutation in the EGF receptor tyrosine kinase. Genes Dev 1994, 8:399-413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu C, Keivens VM, TE OT, McDonald JA, Ginsberg MH: Integrin activation and cytoskeletal interaction are essential for the assembly of a fibronectin matrix. Cell 1995, 83:715-724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu C: Roles of integrins in fibronectin matrix assembly. Histol Histopathol 1997, 12:233-240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams JC, Watt FM: Fibronectin inhibits the terminal differentiation of human keratinocytes. Nature 1989, 340:307-309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]