Abstract

Both type II collagen and the proteoglycan aggrecan are capable of inducing an erosive inflammatory polyarthritis in mice. In this study we provide the first demonstration that link protein (LP), purified from bovine cartilage, can produce a persistent, erosive, inflammatory polyarthritis when injected repeatedly intraperitoneally into BALB/c mice. We discovered a single T-cell epitope, located within residues 266 to 290 of bovine LP (NDGAQIAKVGQIFAAWKLLGYDRCD), which is recognized by bovine LP-specific T lymphocytes. We also identified three immunogenic regions in bovine LP that contain epitopes recognized by antibodies in hyperimmunized sera. One of these B-cell regions is found in the most species-variable domain of LP (residues 1 to 36), whereas the other epitopes are located in the most conserved regions (residues 186 to 230 and 286 to 310). The latter two regions contain an AGWLSDGSVQYP motif shared by the G1 globulin domain of aggrecan core protein, versican, neurocan, glial hyaluronan-binding protein, and the hyaluronan receptor CD44. Our data reveal that the induction of arthritis is associated with antibody reactivities to B-cell epitopes located at residues 1 to 19. Together, these observations show that another cartilage protein, LP, like type II collagen and the proteoglycan aggrecan, is capable of inducing an erosive inflammatory arthritis in mice and that the immunity to LP involves recognition of both T- and B-cell epitopes. This immunity may be of importance in the pathogenesis of inflammatory joint diseases, such as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, in which cellular immunity to LP has been demonstrated.

Immunity to articular cartilage may play an important role in the development and chronicity of erosive inflammatory arthritis, such as is observed in diseases like adult and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. 1 There have been many reports describing cellular and humoral immunity to type II collagen. 1,2 Type II collagen is found in cartilage, as well as in the vitreous humor of the eye. When injected into selected strains of mice and rats and into nonhuman primates, type II collagen causes an inflammatory arthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis. 1-3 Another cartilage-specific molecule is the large proteoglycan called aggrecan. 3,4 Patients with inflammatory arthritis exhibit cellular immunity to this molecule. 5-7 Injection of human fetal aggrecan, from which chondroitin sulfate chains have been removed, plus adjuvant, into BALB/c mice induces an erosive polyarthritis and spondylitis. 8,9 CD4+ T cells are actively involved in the pathogenesis of the arthritis. 10 We have recently shown that the isolated G1 globular domain of aggrecan (G1) is sufficient to induce polyarthritis and spondylitis in mice, 11 and we have identified T- and B-cell epitopes at distinct regions in bovine aggrecan G1 domain. 12

In cartilage matrix, aggrecan binds to hyaluronan via the G1 globular domain (hyaluronic acid binding region). A protein called link protein (LP), 4,13 which shares some structural homology with the G1 domain, 14,15 stabilizes this binding. LP as well as G1 binds to hyaluronan and they bind to each other. We recently showed that the T cells of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis frequently respond to LP, unlike the T cells of nonarthritic controls, in whom such responses are uncommon. 16 In the present study, we show that LP, purified from bovine cartilage, can produce a persistent, erosive, inflammatory polyarthritis when injected repeatedly into BALB/c mice. This immunity involves recognition of a predominant T-cell epitope and B-cell epitopes located in three separate domains. These observations indicate that the immunity to LP is able to induce an erosive inflammatory arthritis and may be of importance in the pathogenesis of these joint diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female BALB/c mice (6 to 8 weeks old, 17 to 20 g) were obtained from Charles River Canada (St. Constant, Quebec, Canada).

Reagents and Culture Media

The following reagents were used: cesium chloride (Kodak Chemicals, Rochester, NY); guanidine hydrochloride, iodoacetamide, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pepstatin A, and ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO); and Freund’s complete adjuvant and incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). The “complete culture medium” (CM) used for lymphocyte cultures was RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 5 × 10−5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Serva Chemie, Heidelberg, Germany), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mmol/L l-glutamine, and 1% nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies). In T-cell proliferation assays, purified protein derivative of tuberculin (Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark) and concanavalin A were used as controls at final concentrations of 10 and 5 μg/ml, respectively. We prepared T-cell growth factors from supernatants of concanavalin A-stimulated spleen cells. Briefly, spleen cells from BALB/c mice were cultured in CM supplemented with 0.1% fresh autologous serum (one spleen per 10 ml of medium) and concanavalin A (5 μg/ml). The cultures were incubated in a humidified incubator with a constant gas flow of 5% CO2 in air. After 24 hours, the cultures were pooled and centrifuged at 900 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatants were collected and stored in aliquots at −20°C until use.

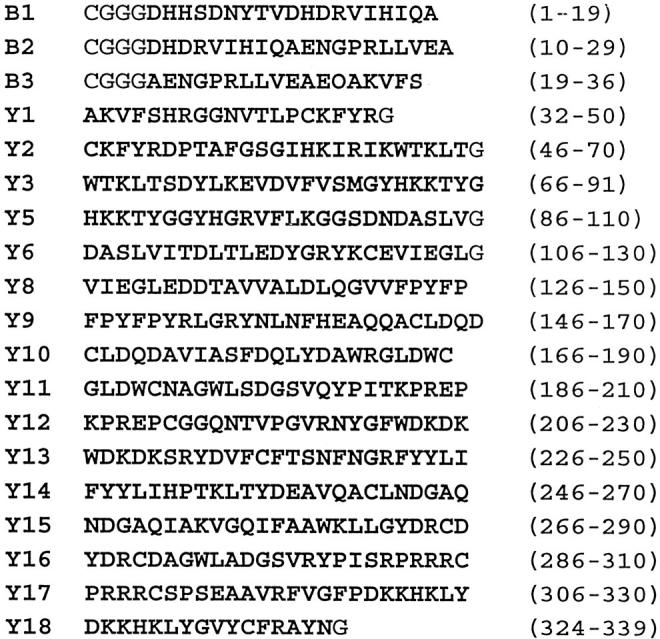

Synthetic Peptides of LP

The synthetic peptides of LP covered the full-length bovine LP sequence, and each peptide overlapped the next by 5 to 10 amino acids (Figure 1) ▶ . They were synthesized using standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry on a solid-phase peptide synthesizer (model 431A; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Crude peptides were purified by reverse-phase chromatography (Prep-10 Aquapore C8 column, Applied Biosystems) using an acetonitrile gradient in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Peptides B1, B2, and B3 have a cysteine at their N terminus followed by three glycine residues as spacers. Other peptides, namely peptide Y1, Y2, Y5, Y6, and Y18, have an additional glycine at the C terminus (Figure 1) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Profile of synthetic peptides used in this study. The bovine LP sequence is based on work done by T. M. Hering, J. Kollar, T. D. Huynh, and L. J. Sandell; National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence identification no., 406053. Light type (lines B1, B2, B3, Y1, Y2, Y5, Y6, and Y18) indicates added amino acids, which are not part of the LP sequence.

LP and Aggrecan

LP and the proteoglycan aggrecan were extracted with 4 mol/L guanidine hydrochloride from adult bovine nasal cartilage and purified as described earlier. 13,17 Briefly, the proteoglycan aggregate fraction A1 was isolated by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation under associative conditions. This contains LP, aggrecan, and hyaluronan. It was then subjected to equilibrium density gradient centrifugation under dissociative conditions to produce an A1D1 fraction (proteoglycan aggrecan) and an A1D3 fraction. The A1D3 fraction was chromatographed on Sepharose CL-6B in 4 mol/L guanidine hydrochloride and 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.3. Fractions were collected and monitored at 280 nm for protein and by the 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue assay for sulfated glycosaminoglycan. 18 The peak fractions containing protein were dialysed and further analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with silver staining and by immunoblotting (see below) for LP and for the glycosaminoglycan keratan sulfate (KS) of aggrecan and G1 domain. 11 Fractions containing LP, free of detectable KS and G1, were used as the antigen. LP was also isolated from trypsin-treated bovine aggrecan aggregate fraction (A1A1). 19 The protein content was determined by the Lowry assay. 20

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

The primary contaminant of LP is the G1 globular domain of aggrecan. This has recently been shown to contain KS, 21 which is immunodetectable using the monoclonal antibody AN9P1. 11 Alternatively, G1 can also be demonstrated by specific monoclonal (1C6) or polyclonal antibodies. In an effort to identify any G1 contamination of the LP, preparations were electrophoresed on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis minigel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA) under reducing conditions. They were silver stained for protein. Alternatively, after electrophoresis, the proteins were electrotransferred (60 V, 300 mA) for 60 minutes in 50 mmol/L Tris-glycine with 20% methanol onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose membrane was immunoblotted with the mouse monoclonal antibody 8A4 (immunoglobulin (Ig) G2b) to LP, 22 with the monoclonal antibody AN9P1 (IgG2a) specific for KS chains, 23 and with aggrecan G1-specific mouse monoclonal antibody 1C6 24 or polyclonal rabbit anti-bovine G1 antiserum that was prepared in our laboratory according to the method described elsewhere. 25 Briefly, the membrane was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hour, and individual lanes were cut out. The lanes were incubated with the different antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature with shaking, followed by three washes in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 for 5 minutes. Goat anti-mouse IgG (Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, Ontario) conjugated with alkaline phosphatase was then incubated with the membranes at room temperature for 1 hour followed by three washes in PBS-0.1% Tween 20. Specific antibody binding was visualized by addition of the insoluble alkaline phosphatase substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium (Bio-Rad).

Induction of Arthritis

Arthritis was induced in BALB/c mice using a protocol described earlier for aggrecan 8 but with some modifications. Briefly, mice were immunized with 25 μg of adult nasal bovine LP per intraperitoneal injection. LP was injected in an emulsion of 50 μl of 50 mmol/L Tris-NaCl buffer, with 50 μl of Freund’s complete adjuvant (day 0), or with 50 μl of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant on days 15, 43, 71, and 99. The injections were stopped when arthritis appeared but continued for the nonarthritic mice up to a maximum of five injections. Injected mice were examined for clinical signs of arthritis every 2nd day as previously described. 10 Briefly, joints of front and rear paws and ankles were examined for swelling, redness, and limitation of movement. Severity scores were determined on a scale of 0 to 4 for each front paw or rear paw/ankle as follows: grade 1, mild redness and swelling in one or more joints; grade 2, moderate redness and swelling in one or more joints; grade 3, severe redness and swelling involving the whole paw; and grade 4, grade 3 plus loss of movement in the affected joint. The sum of arthritic scores in all four paws was taken as the severity score of the mouse. Thus, the maximum possible score was 16.

Histology

Fore and hind paws, ankles, knees, and spines were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, decalcified, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin by standard techniques.

Antigen-Specific T-Cell Lines

Long-term culture of specific T-helper cell lines was established essentially as described. 26 Briefly, BALB/c mice were inoculated with 60 μg of protein or peptide emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant in the hind footpads of one foot. Seven to 9 days later, the enlarged draining lymph nodes were removed, and a single cell suspension was prepared. The lymphocytes were incubated in CM containing 1% fresh mouse serum in the presence of antigen for 3 days. The activated T lymphoblasts were then separated by gradient centrifugation and propagated in CM containing 15% T-cell growth factor with restimulation every 10 to 15 days.

T-Cell Proliferation Assay

T cell lines (3 to 4 × 10 4 cells/well) and irradiated (4000 rads) syngeneic spleen cells (1 × 106/well), as a source of antigen-presenting cells, were co-cultured with the optimal dose of LP (20 μg/ml) or peptides (20 μg/ml) in 200 μl of CM in round-bottomed microtiter plates (Nunc, Naperville, IL). After 48 hours, the cultures were labeled with tritiated thymidine (0.2 μCi/well; Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL) and harvested 12 to 16 hours later with a Titertek multiple harvester (Flow Laboratories, McLean, VA). Cell-associated radioactivity was determined by β-scintillation counting.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs) for Determining Antibody Titer to LP and Specificity

Blood samples were collected by retro-orbital bleeding. The sera were used for a standard ELISA. Briefly, LP (50 ng per well) or each individual LP peptide was diluted to 20 μg/ml in 0.1 mol/L carbonate buffer, pH 9.2, and 50 μl (1 μg) was added to each well of an Immulon-2 flat-bottom microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., Chantilly, VA). After 24 hours at 4°C, the plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% v/v Tween-20 (PBS-Tween, Sigma). Noncoated sites were blocked with 150 μl/well of 1% (w/v) casein (Fisher Scientific Inc., Springfield, NJ) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The plates were washed three times with PBS-Tween. Then 50 μl serum (diluted to 1:200) from LP-hyperimmunized BALB/c mice were added to individual wells. After 90 minutes at room temperature, the plates were washed three times with PBS-Tween. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig diluted at 1:1000 in PBS-Tween was added at 50 μl/well. After 1 hour at room temperature, the plates were washed three times with PBS-Tween. Finally, 50 μl of freshly prepared alkaline phosphatase substrate (disodium p-nitrophenol phosphate, Sigma) at 0.5 mg/ml in 8.9 mmol/L diethanolamine and 0.25 mmol/L MgCl2, pH 9.8, was added to each well for 20 to 30 minutes at room temperature. The absorbencies were measured at 405 nm on an ELx808 plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT).

Results

Analysis of Purity of Bovine LP Preparation

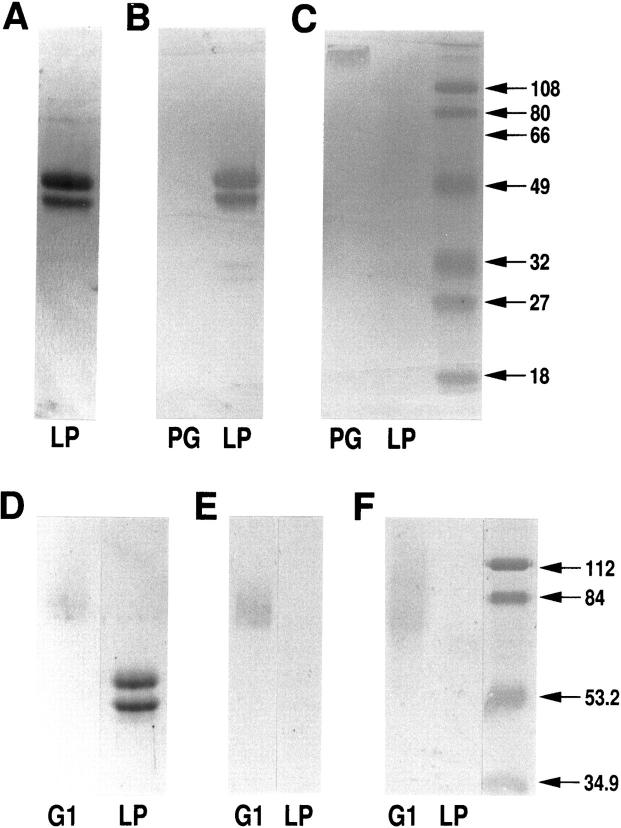

To ensure that LP did not contain the G1 domain of aggrecan or any other molecules, purified LP was electrophoresed on an SDS acrylamide gel under reducing conditions and silver stained. Figure 2A ▶ shows that the characteristic 45- and 49-kd subunits of LP were detected with silver staining. A very faint sharp doublet of higher molecular weight is shown in the LP preparation (Figure 2A) ▶ . These additional band(s) in Figure 2A ▶ are not likely due to a contamination of G1 domain, because G1 bands are usually broad and faint, as shown in Figure 2, D through F ▶ , because of varying glycosylation. Moreover, Western blot analysis, with the LP-specific monoclonal antibody 8A4 (Figure 2B) ▶ , KS epitope-specific monoclonal antibody AN9P1 (Figure 2C) ▶ , aggrecan G1-specific monoclonal antibody 1C6 24 (Figure 2E) ▶ , or polyclonal rabbit anti-bovine G1 antiserum (Figure 2F) ▶ , further demonstrated the absence of contaminating proteoglycan or G1 domain. Therefore, there was no evidence for the presence of high molecular weight G1 domain in our LP preparation.

Figure 2.

Analysis of purity of bovine LP preparation by SDS electrophoresis and Western blotting. A: One μg of purified LP was electrophoresed on a 10% SDS acrylamide gel under reducing conditions and silver stained. The characteristic two subunits of bovine LP 12 are clearly visible. Purified LP (1 μg) and bovine aggrecan (PG, 1 μg dry weight) (B and C) or G1 protein and LP (D through F) were electrophoresed and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then immunoblotted with LP-specific monoclonal antibody 8A4 (B), the KS-specific monoclonal antibody AN9P1 (C), the G1-specific monoclonal antibody 1C6 (E), or the G1-specific polyclonal antibody (F). In B, both LPs react with antibody 8A4. In C, only aggrecan at the origin is reactive in the lane containing PG. In E and F, there is no trace of G1 domain in LP preparation using mono- or polyclonal anti-G1 antibodies. The relative positions of G1 (D) and LP (A and D) are shown with Coomassie blue staining or silver staining.

Induction of Arthritis by LP

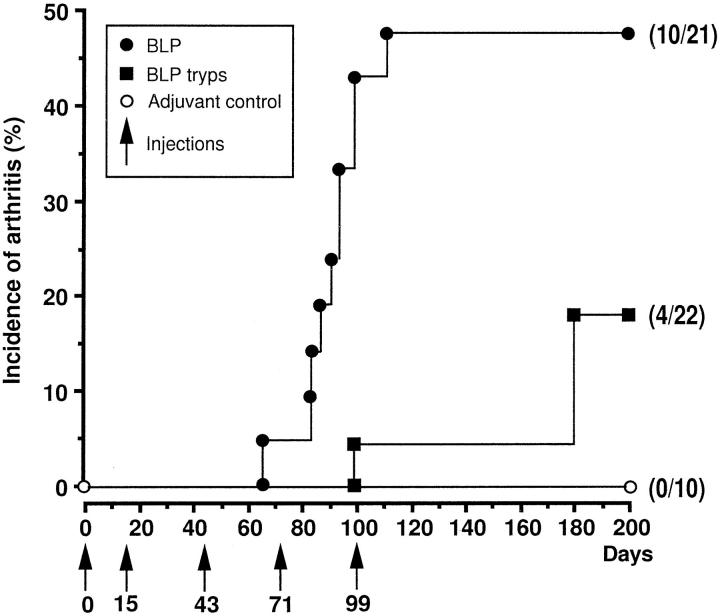

BALB/c mice injected with bovine LP developed an erosive inflammatory arthritis (Figures 3 and 4) ▶ ▶ . In half of mice (n = 10/21), bovine LP produced a clinically and histologically defined arthritis (Figure 4) ▶ that was of moderate severity (mean 4.5) and located in the front and rear paws and ankles (Figure 4) ▶ . Bovine LP isolated from trypsin-digested proteoglycan aggregate, which lacks the first 13 N-terminal residues, 27 produced a lower incidence of arthritis (n = 4/22, Figure 3 ▶ ). No arthritis developed in animals immunized with adjuvant only (n = 0/10). The arthritis produced by bovine LP had a mean onset of 88 days and reached its highest incidence at days 100 to 120. The joint swelling persisted in some animals up to at least day 145 when observations were discontinued because of ethical limitations. In general, the arthritis was less severe than the arthritis induced by the aggrecan G1 domain 11 but presented in a similar manner.

Figure 3.

Induction, incidence, and onset of arthritis in mice injected with bovine LP. BALB/c mice were immunized with 25 μg of native bovine LP (•–•, n = 21) or trypsinized bovine LP (▪–▪, n = 22) per intraperitoneal injection in an emulsion of 50 μl of Tris-NaCl buffer in 50 μl of Freund’s complete adjuvant (day 0) or in 50 μl of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (days 15, 71, and 99; arrows). Controls (○, n = 10) were immunized with the same amount of adjuvant without antigen.

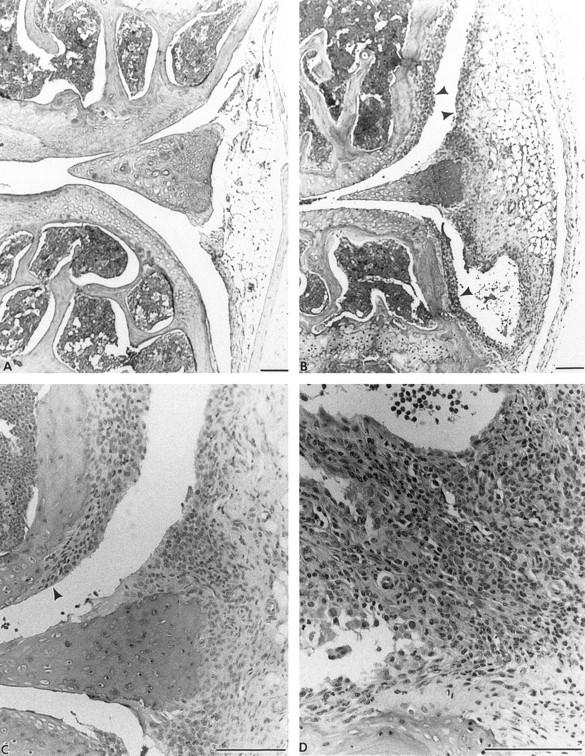

Figure 4.

The histology (H&E) of nonarthritic (A) and arthritic (B through D) joints of mice injected or not injected with bovine LP. A: Nonarthritic knee to show joint cavity, articular cartilages, and meniscus. B: Arthritic knee indicating synovitis (arrowheads) 20 days after onset. C: A high-power view of B to show pannus formation (arrowhead) and synovitis. D: Mononuclear infiltration in arthritic front paw 16 days after onset, which was usually seen throughout the paw. Bars = 100 nm.

Histological Analyses

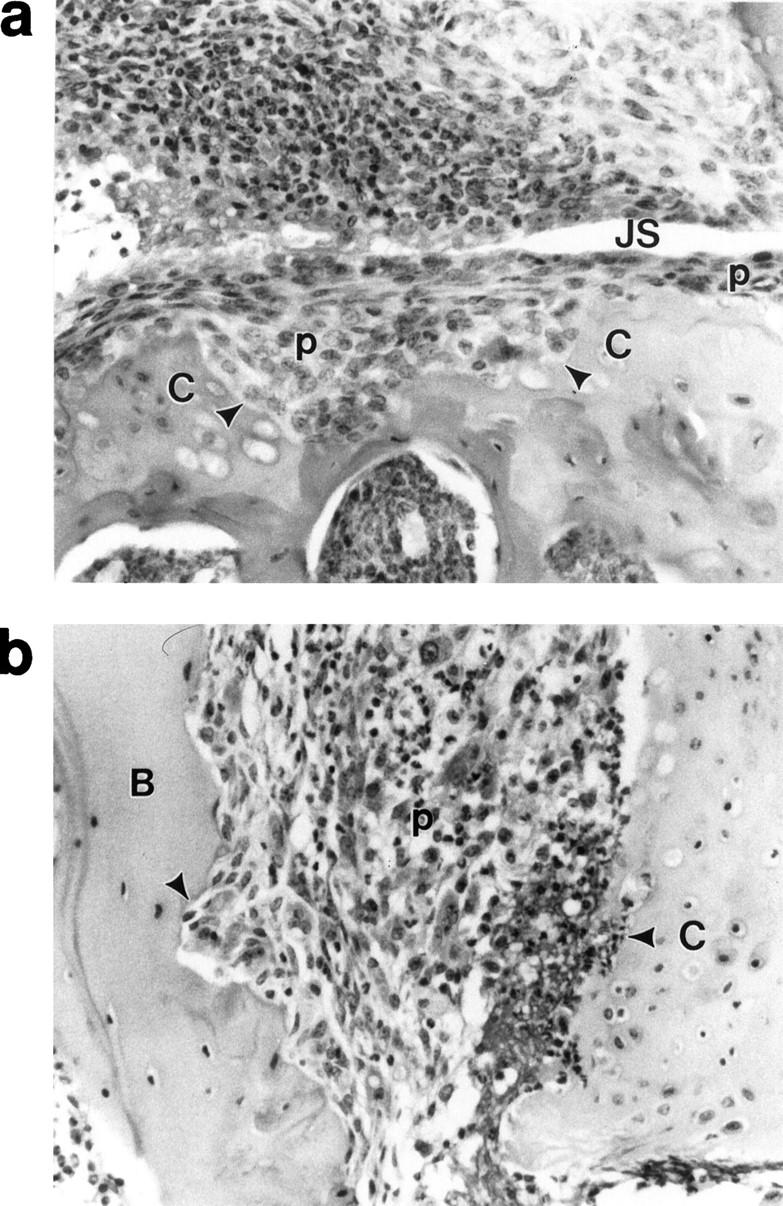

Examination of all paws, ankles, knees, and spines of mice injected with LP within 2 weeks of onset of arthritis revealed that the swelling, redness, and deformity observed in affected paws and ankles always involved extensive mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration. In the paws, this was seen around the tarsal and metatarsal joints as well as carpal, metacarpal, and phalangeal joints (Figure 4D) ▶ . This resulted in pannus formation and synovitis (Figure 4, B and C) ▶ . An extensive erosive destruction of cartilage and bone was observed in association with a pronounced synovitis with pannus formation 85 days after LP immunization (Figure 5, a and b) ▶ . Polymorphonuclear leukocytes were commonly seen in joint cavities and synovia but were absent from the joints of control animals. Synovitis and joint destruction were never observed in the control animals (Figure 4A) ▶ . Spines all appeared normal in mice injected with LP (data not shown). There was, therefore, no evidence of the spondylitis that we have observed in mice injected with the G1 globular domain of bovine aggrecan (after removal of KS) 11 or with human fetal aggrecan (after removal of chondroitin sulfate). 8

Figure 5.

Cartilage and bone erosions in LP-induced arthritis in BALB/c mice. a: Erosion (arrowheads) of tibial cartilage by inflammation tissue (pannus, p) in a knee joint of a mouse 85 days after the initial immunization with LP. The joint space (JS) is also shown. b: Erosion (arrowheads) of cartilage (C) and bone (B) by inflammatory tissue (p) in hind foot 85 days after initial immunization with LP. No articular cartilage remains on the bone, having been destroyed by the inflammatory tissue.

Mapping of T-Cell Epitope in LP

We were unsuccessful in generating T-cell lines to purified LP. However, five T-cell lines, three raised to a peptide mixture covering the whole LP and two to peptide Y15, were generated from different animals as described in Materials and Methods. All of the T-cell lines were of the CD3+, CD4+, and CD8− phenotype (data not shown) and responded well to native LP, but did not respond to native or KS chain-depleted G1 domain of aggrecan or type II collagen. Table 1 ▶ shows the results of T-cell proliferation assays against native LP and the overlapping synthetic LP peptides (Figure 1) ▶ . All of the T-cell lines responded to peptide Y15, but not to any other LP peptides (Table 1) ▶ . We have thus identified a single T-cell epitope of LP located within residues 266 to 290 and shown that this epitope can be actively processed and presented by antigen-presenting cells using native LP.

Table 1.

Mapping of T-Cell Epitope in Bovine LP (BLP)

| T cell line | PPD | GIKS | BLP | B1 | B2 | B3 | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y5 | Yc6 | Y8 | Y9 | Y10 | Y11 | Y12 | Y13 | Y14 | Y15 | Y16 | Y17 | Y18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBLP | <2 | <2 | 17.1 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | 2.0 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | 58.2 | <2 | <2 | <2 |

| MY15 | ND | <2 | 20.3 | <2 | 2.9 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | 2.1 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | 18.6 | <2 | <2 | 2.4 |

MBLP and MY15 were representative T cell lines generated from draining lymph node of BALB/c mice immunized with a peptide cocktail covering the whole bovine LP or peptide Y15, respectively. These cells were tested for proliferation in the presence of an optimal dose of PPD (10 μg/ml), native bovine LP (BLP 20 μg/ml), keratan sulfate depleted aggrecan G1 domain (G1KS) (20 μg/ml, or synthetic LP peptides (B1 to Y18, 10μg/ml). The results are expressed as stimulation index (S.I.). S.I. = experimental mean cpm − control mean cpm/control mean cpm.

PPD, purified protein derivative of tuberculin; ND, not determined.

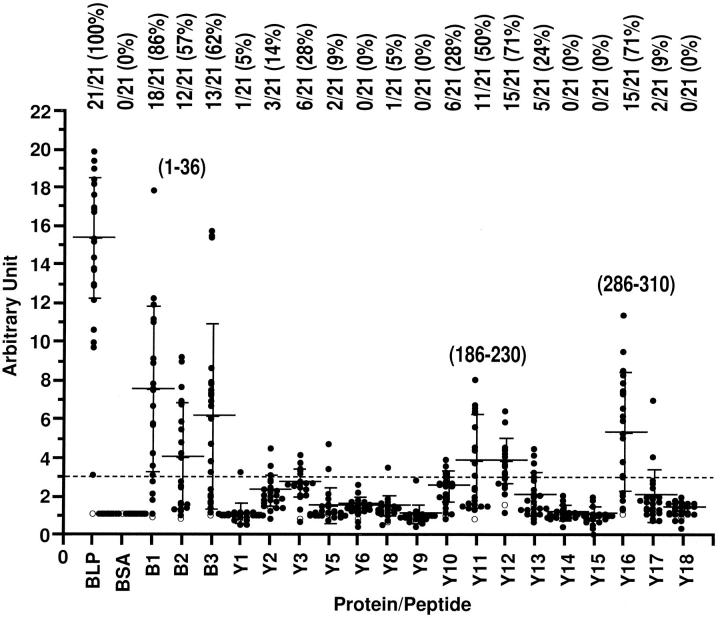

Mapping of Immunogenic Regions of LP Recognized by B Cells

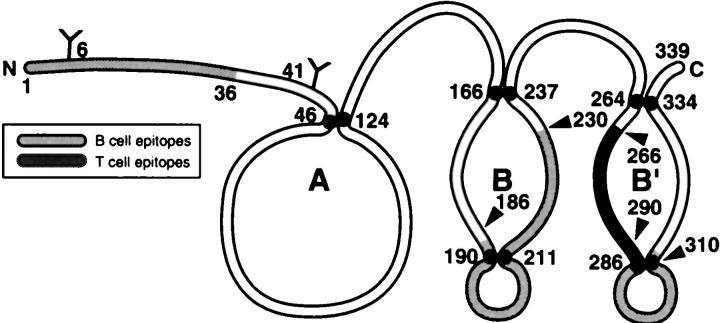

To identify immunogenic region(s) and arthritis-related B-cell epitope(s) in LP, sera were collected from LP-immunized BALB/c mice at an early stage in immunization before the onset of arthritis (day 29) and also on the day when clinical symptoms appeared (day 58 to 113). These sera were assessed by an ELISA against LP, as well as by using a set of synthetic LP peptides. BSA was used as a control. All of the sera (n = 21) showed binding to native LP, whereas none bound to BSA, the control protein. There were three main regions recognized, represented by peptides covering residues 1 to 36, 186 to 230, and 286 to 310 (Figure 6) ▶ . Residues 1 to 36 (peptides B1, B2, and B3) constitute the N-terminal end of the molecule, which is the most variable region of LP. Removal of amino acids 1 to 13 by trypsin from this area results in reduced arthritis incidence (Figure 3) ▶ . In contrast, residues 186 to 230 (peptides Y12 and Y13) and 286 to 310 (peptide Y16) are located within the most conserved regions, around the second and third cysteines of loops B and B′ of LP (Figure 7) ▶ . Both regions are homologous in humans, 28 cows (T. M. Hering, J. Kollar, T. D. Huynh, L. J. Sandell, unpublished data), and rats. 29 The mouse LP sequence is not yet published.

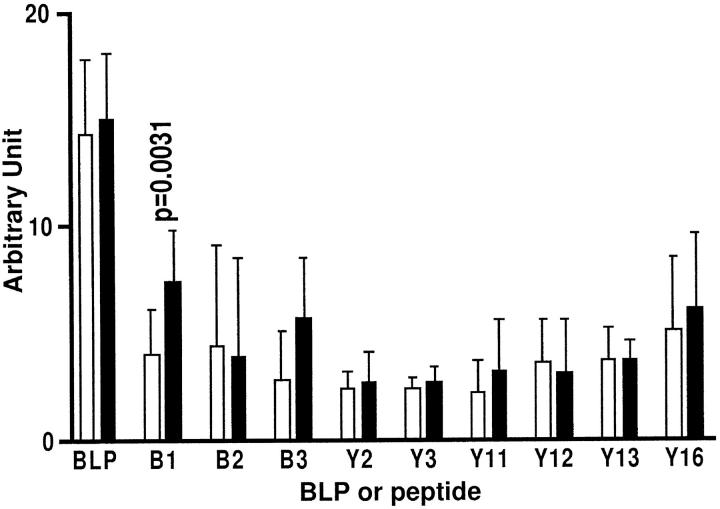

Figure 6.

Identification of B-cell immunogenic regions on bovine LP. Serum isolated from one normal BALB/c mouse (○) and sera isolated from BALB/c mice (n = 21, •) on day 85 after hyperimmunization with native bovine LP were assayed for their reactivity to bovine LP (BLP) or LP peptides. The background responses to BSA were all in the range from 0.58 to 0.91. The arbitrary unit was calculated as the experimental optical density value divided by background (BSA) optical density value, and units exceeding 3 (broken line) were recorded as a positive reaction. Also shown are the proportion of positive to total reactions and the positive percentage (top), mean ± SD (bars), and residue position of reactive peptides (1 to 36, 186 to 230, and 286 to 310).

Figure 7.

Profile of T- and B-cell epitope distribution in bovine LP. The diagram shows the major immunogenic regions recognized by B cells (pale gray) and by T cells (dark gray) in LP. An Ig-like loop A and two closely related structures of loop B and B′ are also shown.

We analyzed the B-cell epitope recognition patterns between arthritic (n = 10) and nonarthritic (n = 11) mice within these immunogenic regions. The results demonstrate that the arthritis-associated B-cell epitope is located within the first 19 amino acid residues (peptide B1) (Figure 8) ▶ . Although the response to peptide B3 (residues 29 to 36) is higher in the arthritic group, this difference was not quite significant (P = 0.0573) by the Mann-Whitney U test (Figure 8) ▶ .

Figure 8.

Identification of arthritis-associated B cell-recognizing regions on bovine LP. The sera of 10 arthritic mice (▪) were collected on the day arthritis developed (day 58 to 113), and sera of nonarthritic animals were also collected over the same period of time (n = 11, □) and were assessed for their binding to BSA, LP, and individual LP synthetic peptides using an ELISA. The results are expressed as arbitrary units, calculated as experimental optical density value divided by the background optical density value. Statistical significance between arthritic and nonarthritic animals was assessed by Mann-Whitney U test. The P value with significant difference between the arthritic and nonarthritic groups is shown.

Discussion

Immunity to cartilage antigens may play a role in the pathogenesis of human inflammatory joint diseases. In addition to collagen type II, injection of human or bovine aggrecan into mice induces an erosive polyarthritis. 8,9 We have shown that the G1 globular domain of aggrecan alone can induce polyarthritis, which is often accompanied by spondylitis, a feature not seen in type II collagen-induced arthritis. 11 This only occurs, however, if the G1 preparation is treated with keratanase to remove KS. In this study, we show that immunity to purified bovine LP lacking the G1 domain (and not treated with keratanase), which is a protein structurally similar to the G1 domain of aggrecan and which can also bind hyaluroran, can also induce an erosive polyarthritis in BALB/c mice of the kind induced by aggrecan G1 protein and collagen type II, 2 IX, and XI. 30 After immunization with LP, free of G1 domain, about half the mice developed a persistent erosive polyarthritis (Figure 3) ▶ , determined both clinically and histologically (Figures 4 and 5) ▶ ▶ . There was no histological evidence of spondylitis (data not shown), which is observed on immunization with the keratanase-treated G1 domain. 11 The LP arthritis is milder but persistent and is thereby distinguished from proteoglycan and G1 domain-induced polyarthritis in BALB/c mice. Although our LP preparation may have been contaminated with an amount of the aggrecan G1 protein too small to detect even with our very sensitive methods, contamination is very unlikely, because the arthritogenic ability of the bovine G1 is wholly dependent on the removal of KS chains from G1 protein, 11 and our LP was never treated in this way. Moreover, there was also no spondylitis with LP.

We have identified at least one major T-cell epitope in bovine LP (Table 1) ▶ located at residues 266 to 290 of bovine LP (NDGAQIAKVGQIFAAWKLLGYDRCD) using LP- or peptide Y15-specific T-cell lines. It is premature to conclude that this is the predominant T-cell epitope, because we were unable to isolate T-cell lines and clones using native LP and the peptides that we used overlap by five amino acid residues, whereas typical T-cell determinants consist of eight to nine residues. One important feature of T cell-recognizing epitope 266 to 290 is their cross-reactivity to native LP, indicating that peptide 266 to 290 contains a functional T-cell epitope, especially because the antigen-presenting cells from mice can process and present native LP to these T-cell lines (Table 1) ▶ . It remains to be established whether the T-cell response to epitope 266 to 290 is involved in the induction of arthritis.

In human arthritis, the immune system is probably exposed to the Gl globular domain and LP, because molecules such as aggrecan and LP are released from cartilage and are detectable by immunoassay in synovial fluid. 1 Our recent studies also demonstrate that cellular immunity to human and bovine LP, either as the native protein or in the form of synthetic polypeptides, is frequently observed in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, compared with nonarthritic age and sex-matched controls. Moreover, in these patients, there was a significant correlation between cellular immunity to LP and clinically measured disease activity. 16

Although the present antibody analyses have some limitations in that we used bound peptides, and this may preclude detection of epitopes through masking of peptide binding site(s), we have never encountered this problem in studies of antibodies to peptides and their known proteins. Our study of antibodies in these mice did, however, reveal some associations with arthritis induction. Using this approach whereby peptides were used, we found that the antibodies in sera from LP-hyperimmunized mice reacted mainly with three domains of LP. One was located at the N terminus, the most variable region of LP at residues 1 to 36. The other two domains were located at corresponding regions of loops B and B′, at residues 186 to 230 and 286 to 310, respectively (Figures 6 and 8) ▶ ▶ . Both are located in the most conserved part of the LP molecule. The sequences of these two regions show complete homology in human, 28 cow (T. M. Hering et al, unpublished data), and rat LP. 29 The sequence of mouse LP is not yet available. Moreover, both regions include a AGWLSDGSVQYPI motif that is repeated twice in LP and four times in proteoglycan aggrecan core protein, and is also shared by the proteoglycans versican, neurocan, the glial hyaluronan-binding protein, and the hyaluronan receptor CD44. 31 Thus, cross-reactivity may occur with these proteins, but this remains to be established.

That the humoral response against N-terminal peptides 1 to 19 was significantly higher in arthritic than in nonarthritic mice (Figure 8) ▶ suggests that humoral immunity to this N-terminal epitope may be associated with the pathogenesis of LP-induced arthritis. The observation that LP isolated from aggrecan aggregate treated with trypsin, which lacks 13 residues of the N-terminal domain, 32 has a reduced capacity to induce arthritis (Figure 2) ▶ also points to the importance of this domain and to a role for humoral immunity to this region in disease induction. Amino-terminal peptides up to 30 residues in length are preferentially removed by extracellular cleavage of LP in proteoglycan aggregates by a variety of proteases. 32 In vivo, this N-terminal segment is lost from human cartilage. 32 Hence, these peptides are probably released from articular cartilage during the normal process of turnover and aging, leading to their uptake and recognition by cells of the immune system, such as monocytes and B cells. 33 We have also observed that human LP can also induce arthritis in BALB/c mice and that the antibodies that bind to bovine LP residues 1 to 15 and 23 to 36 often cross-reacted strongly with the human LP peptides from the same region (Y. Zhang and A. R. Poole, unpublished data). In summary, although we are limited by our existing ELISA system, being aware that only linear epitopes have been identified, which may not represent all such epitopes, we believe that these B-cell epitope analyses are of value in identifying immunogenic domains of LP in BALB/c mice. There are two oligosaccharide attachment sites in the N terminus of LP. They may influence antibody recognition and may be important in inducing arthritis. Studies are planned to determine the predominance of antibodies to LP epitopes in immunity to whole LP. We are currently interested to see whether an immunization of BALB/c mice with these T- and B-cell epitope peptides will lead to induction of arthritis.

These collective observations draw attention to the fact that LP, as well as other cartilage molecules that are capable of inducing a rheumatoid-like arthritis in mice, may also serve as an autoantigen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Of equal interest, LP is not entirely restricted to cartilage in its distribution in the body, although hyaline cartilage is the principal tissue in which it is concentrated. We and others have shown previously that it is also present in the aortic media, 34,35 the central nervous system, and the sclera, 33 where it may serve to stabilize the binding of aggregating proteoglycans to hyaluronic acid found in these tissues. Thus, as suggested previously, 34 some extra-articular complications of rheumatic disease 36 may involve and be caused by immunity to matrix LP. Our study draws further attention to the capacity of different cartilage antigens to induce a persistent inflammatory erosive polyarthritis in experimental animals. Hence, these different cartilage molecules may act as autoantigens in human arthritis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Virabhadzachari Vipparti for purification of LP, Isabelle Pidoux-Perera for assistance with the microphotography, and Jane Wishart for the artwork.

Footnotes

Funded by the Shriners of North America (to YZ and ARP), Riva Foundation (to ARP), and U.S. Public Health Service grants AR34614 and AR21498 (to LCR).

Address all correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Yiping Zhang, Joint Diseases Laboratory, Shriners Hospital for Children, 1529 Cedar Avenue, Montreal, Quebec, H3G 1A6, Canada. E-mail: yzhang@shriners.mcgill.ca.

References

- 1.Poole AR: Immunology of cartilage. ed 2 Moskowitz RW Howell DS Goldberg VM Mankin HJ eds. Osteoarthritis Diagnosis and Medical/Surgical Management, 1992, :pp 155-189 WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuart JM, Watson WC, Kang AH: Collagen autoimmunity and arthritis. FASEB J 1988, 2:2950-2956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poole AR: Cartilage in health and disease. ed 12 McCarty DJ Koopman W eds. Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A Textbook of Rheumatology, 1993, :279-333 Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neame PJ, Barry FP: The link proteins. Jollés P eds. Proteoglycans. 1994, :pp 53-72 Birkhauser Verlag Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glant T, Csongar J, Szucs T: Immunopathologic role of proteoglycan antigens in rheumatoid joint disease. Scand J Immunol 1980, 11:247-252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golds EE, Stephen IBM, Esdaile JM, Strawczynski H, Poole AR: Lymphocyte transformation to connective tissue antigens in adult and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus and a non-arthritic control population. Cell Immunol 1983, 82:196-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikecz K, Glant TT, Baron M, Poole AR: Isolation of proteoglycan-specific T lymphocytes from patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Cell Immunol 1988, 112:55-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glant TT, Mikecz K, Arzoumanian A, Poole AR: Proteoglycan-induced arthritis in BALB/c mice: clinical features and histopathology. Arthritis Rheum 1987, 30:201-212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikecz K, Glant TT, Poole AR: Immunity to cartilage proteoglycans in BALB/c mice with progressive polyarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis induced by injection of human cartilage proteoglycan. Arthritis Rheum 1987, 30:306-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee S, Webber C, Poole AR: The induction of arthritis in mice by the cartilage proteoglycan aggrecan: role of CD4+ and CD8+ cells. Cell Immunol 1992, 144:347-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leroux J-Y, Guerassimov A, Banerjee S, Cartman A, Rosenberg LC, Poole AR: Immunity to the G1 globular domain of the cartilage proteoglycan aggrecan can induce inflammatory erosive polyarthritis and spondylitis in BALB/c mice but immunity to G1 is inhibited by covalently bound keratan sulfate in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest 1995, 97:621-632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Guerassimov A, Leroux J-Y, Cartman A, Webber C, Lalic R, de Miguel E, Rosenberg LC, Poole AR: Arthritis induced by proteoglycan aggrecan G1 domain in BALB/c mice: evidence for T cell involvement and the immunosuppressive influence of keratan sulfate on recognition of T- and B-cell epitopes. J Clin Invest 1998, 101:1678-1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang L-H, Rosenberg L, Reiner A, Poole AR: Proteoglycans from bovine nasal cartilage: properties of a soluble form of link protein. J Biol Chem 1979, 254:10523-10531 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barta E, Déak F, Kiss I: Evolution of the hyaluronic-binding module of link protein (Letter). Biochem J 1993, 292:947-949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neame PJ, Christner JE, Baker JR: Cartilage proteoglycan aggregates: the link protein and proteoglycan amino-terminal globular domains have similar structures. J Biol Chem 1987, 262:17768-17778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerassimov A, Duffy C, Zhang Y, Banerjee S, Leroux J-Y, Reimann S, Webber C, Delaunay N, Vipparti V, Ronbeck L, Cartman A, Arsenault L, Rosenberg LC, Poole AR: Immunity to cartilage link protein in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1997, 24:959-964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roughley PJ, Poole AR, Mort JS: The heterogeneity of link proteins isolated from human articular proteoglycan aggregates. J Biol Chem 1982, 257:11908-11914 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ: Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochim Biophys Acta 1986, 883:173-177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leroux J-Y, Poole AR, Webber C, Vipparti V, Choi HU, Rosenberg LC, Banerjee S: Characterization of proteoglycan-reactive T cell lines and hybridomas from mice with proteoglycan-induced arthritis. J Immunol 1992, 148:2090-2096 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowry OH, Roseborough NJ, Farr AC, Randall RJ: Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 1951, 193:265-275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry FP, Rosenberg LC, Gaw JU, Koob TJ, Neame PJ: N- and O-linked keratan sulfate on the hyaluronan binding region of aggrecan from mature and immature cartilage. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:20516-20524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caterson B, Baker JR, Christner JE, Lee Y, Lentz M: Monoclonal antibodies as probes for determining the microheterogeneity of the link proteins of cartilage proteoglycans. J Biol Chem 1985, 260:11348-11356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole AR, Webber C, Reiner A, Roughley P: Studies of a monoclonal antibody to skeletal keratan sulphate: importance in antibody valency. Biochem J 1989, 260:849-856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens JW, Oike Y, Handley C, Hascall VC, Hampton A, Caterson B: Characteristics of the core protein of the aggregating proteoglycan from the Swarm rat chondrosarcoma. J Cell Biochem 1984, 26:247-259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura JK, Thonar EJ-M, Hascal VC: Identification of core protein, an intermediate in proteoglycan biosynthesis in cultured chondrocytes from the Swarm chondrosarcoma. J Biol Chem 1981, 256:7890-7897 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Barkas T, Juillerat M, Schwendimann B, Wekerle H: T cell epitopes in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis of the rat: strain-specific epitopes and cross-reaction between two distinct segments of the α chain of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (Torpedo californica). Eur J Immunol 1988, 18:551-557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Cassidy D, Allen A, Neame PJ, Mort JS, Roughley PJ: Link protein shows species variation in its susceptibility to proteolysis. J Orthop Res 1992, 10:621-630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudhia J, Hardingham TE: The primary structure of human cartilage link protein. Nucleic Acids Res 1990, 18:2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doege K, Hassel JR, Caterson B, Yamada Y: Link protein cDNA sequence reveals a tandemly repeated protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986, 83:3761-3765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boissier M-C, Chiocchia G, Rouziere M-C, Herbage D, Fournier C: Arthritogenicity of minor cartilage collagens (types IX and XI) in mice. Arthritis Rheum 1990, 33:1-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldenstein LA, Zhou DFH, Picker LJ, Minty CN, Bargatze RF, Ding JF, Butcher EC: A human lymphocyte homing receptor, the Hermes antigen, is related to cartilage proteoglycan core and link protein. Cell 1989, 56:1063-1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen Q, Liu J, Roughley PJ, Mort JS: Link protein as a monitor in situ of endogenous proteolysis in adult human articular cartilage. Biochem J 1991, 278:143-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin H, Dean MF: An N-terminal peptide from link protein is rapidly degraded by chondrocytes, monocytes, and B cells. Eur J Biochem 1993, 212:87-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poole AR, Pidoux I, Reiner A, Cöster L, Hassell JR: Mammalian eyes and associated tissues contain molecules that are immunologically related to cartilage proteoglycan and link protein. J Cell Biol 1982, 93:910-921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardell S, Baker J, Caterson B, Heinegård D: Link protein and a hyaluronic acid-binding region as components of aorta proteoglycan. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1980, 95:1823-1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferry AP: The eye and rheumatic diseases. Textbook of Rheumatology, ed 4. Edited by WN Kelley, ED Harris Jr, S Ruddy, CB Sledge. Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co, pp 507–508