Abstract

Background

Little is known about the effect of diabetes mellitus on subsequent lower body disability in older Mexican Americans, one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States. The aim of this study is to examine the relationship between diabetes mellitus and incident lower body disability over a 7-year follow-up period.

Methods

Ours was a 7-year prospective cohort study of 1835 Mexican-American individuals ≥65 years old, nondisabled at baseline, and residing in five Southwestern states. Measures included self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes, stroke, heart attack, hip fracture, arthritis, or cancer. Disability measures included activities of daily living (ADLs), mobility tasks, and an 8-foot walk test. Body mass index, depressive symptoms, and vision function were also measured.

Results

At 7-year follow-up, 48.7% of diabetic participants nondisabled at baseline developed limitations in one or more measures of lower body function. Cox proportional regression analyses showed that diabetic participants were more likely to report any limitation in lower body ADL function (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.05, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.58–2.67), mobility tasks (HR = 1.69, 95% CI, 1.39–2.04), and 8-foot walk (HR = 1.46, 95% CI, 1.15–1.85) compared with nondiabetic participants, after controlling for relevant factors. Older age and having one or more diabetic complications were significantly associated with increased risk of limitations in any lower body ADL and mobility task at follow-up.

Conclusion

Older Mexican Americans with diabetes mellitus are at high risk for development of lower body disability over time. Awareness of disability as a potentially modifiable complication and use of interventions to reduce disability should become health priorities for older Mexican Americans with diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most prevalent and disabling chronic diseases in the United States (1). In 2002, a total of 18.2 million people of all ages had DM (1). DM has its greater effects on elderly persons, women, and certain racial and ethnic groups (2). One in five adults aged 65 or older has DM (2). On average, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and Alaska Native adults are two to three times more likely to have DM compared to non-Hispanic whites (1–3).

DM is a leading cause of disability among older adults and often results in many limitations in daily activities of life (4). The risk of physical disability increases with age and can significantly impact the quality of life of older people (5,6). Older adults with disability are at higher risk of institutionalization and more likely to utilize health care (5–10).

The disabling effects of DM are multifactorial and include the high prevalence of complications such as stroke, heart attack, peripheral vascular disease, vision impairment, neuropathy, and depression (11). Several cross-sectional studies of older adults with DM have examined the disablement process with its associated comorbidities (12–15) and have found that diabetic persons had a greater prevalence of mobility disability and activities of daily living (ADL) disability. Few longitudinal studies (16–20) have examined the effect of DM on incident functional disability. These studies have found DM to be associated with an increased incidence of functional disability. For instance, Gregg and colleagues (18) assessed incident functional disability in older non-Hispanic women with DM and showed that risk of disability was related to increasing age, cardiovascular heart disease, severe visual impairment, and depressive symptomatology. Similarly, Rodríguez-Saldaña and colleagues (19) and Wu and colleagues (20) have found an increased risk of disability in ADL and instrumental ADL among older Mexicans and older Mexican Americans with DM.

In earlier studies from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (H-EPESE) survey, we demonstrated that DM was associated with a high prevalence of disability (21–23). Little is known about the effect of DM on subsequent subjective and objective measures of disability in older Mexican Americans, one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States. Therefore, we used data from the H-EPESE study to examine the relationship between DM and the incidence of lower body disability over a 7-year follow-up period among older Mexican Americans.

Methods

Sample

Data used were from the H-EPESE, a longitudinal study of Mexican Americans aged 65 and older, residing in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California. The sample and its characteristics have been described elsewhere (24). The present study uses baseline data (1993–1994) and data obtained at 2-, 5-, and 7-year follow-up assessment (2000–2001). The sample consisted of 1835 participants who reported no limitation in ADL (walking across a small room, bathing, transferring from a bed to a chair, and using the toilet) and reported the ability to climb stairs and walk a half mile without help.

Measures

Diabetes mellitus

We assessed DM by asking if participants had ever been told by a doctor that they had DM. Respondents who reported a DM diagnosis were asked about disease duration and treatment received (categorized as: none, oral hypoglycemic, insulin, or oral hypoglycemic–insulin combination). Respondents were asked if they had problems with their kidneys, eyes, or circulation or if they have any amputations due to DM. Sum scores for DM complications ranged from 0 to 4.

Measures of lower body disability

Measures of lower body disability included:

Self-reported limitation in four ADLs (i.e., walking across a small room, bathing, transferring from a bed to a chair, and using the toilet) (25). Respondents were asked if they could do the activities without help, needed help, or were unable to do the activities. Lower body ADL limitation was dichotomized as: no help needed/needing help with or unable to perform one or more ADLs.

Self-reported limitation in two mobility tasks (climbing stairs or walking a half mile). Respondents were asked if they need help or do not need help to perform the activities. Mobility limitation was dichotomized as no help needed/needing help with or unable to perform one or both activities (26).

Performance-based measure of mobility. This measure was assessed with an 8-foot walk timed twice (to the nearest second), using the faster of the two walks for scoring. Walking limitation was defined as being unable to walk or walking the 8-foot walk at a speed of ≥9.0 seconds. Scores were divided into approximate quartiles. A time of ≥9.0 seconds received a score of 1; 6.0–8.0 seconds a score of 2; 4.0–5.0 seconds a score of 3; and ≤3.0 seconds a score of 4; higher scores indicate faster walking speed (27–28).

Covariates

Baseline sociodemographic variables included age and sex. We assessed the presence of other medical conditions by asking if respondents had ever been told by a doctor that they had hypertension, heart attack, stroke, arthritis, cancer, or hip fracture. Depressive symptomatology was measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (29). We consider persons scoring ≥16 to experience high depressive symptomatology (30).

Cognitive function was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) instrument (31,32). Scores range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating poorer cognitive ability. Body mass index was computed as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Participants with a body mass index of ≥30 were considered obese (33).

Near vision was measured using cards, each with seven-digit numbers of three different type sizes: 7-, 10-, and 23-point. Participants held these cards at least 7 inches from their eyes and then were asked to read the numbers. Participants who could only read the 23-point were considered to have near vision impairment. Functional distance vision was measured using a modified Snellen test using directional Es at 4 meters to assess acuity from 20/60 to 20/200. Those participants with vision worse than 20/60 were considered to be impaired (34).

Outcome

Incidence of lower body disability was defined using three outcomes: a) new onset of any ADL lower body limitation (needing help with or unable to perform one or more of the four ADLs) at either 2-, 5-, or 7-year follow-up interview; b) new onset of any mobility limitation (unable to or needing help to walk up and down stairs or to walk a half mile) at either 2-, 5-, or 7-year follow-up interview; and c) walking limitation (unable to perform the walking test or performing it with a walking time of ≥9.0 seconds) at either, 2-, 5-, or 7-year follow-up interview.

Analysis

To compare baseline characteristics by DM status, chi-square statistic and t test were used. Cox proportional hazard regressions were used to estimate the hazard ratio of incidence of lower body disability at 2-, 5-, or 7-year follow-up as a function of a DM diagnosis among the 1835 participants reporting no limitation in ADLs and capable of climbing stairs and walking a half mile without help at baseline. Those participants who died and those who were lost to follow-up were censored at the date of the last follow-up. All analyses were controlled for age, sex, selected medical conditions, vision function, MMSE score, and obesity at baseline. Interaction effects were performed between DM and age, sex, medical conditions, high depressive symptoms, MMSE score, and obesity.

In the subgroup analysis, only nondisabled diabetic subjects (N = 347) were included, and measurements at 2-, 5-, or 7-year time points were analyzed to examine the association of diabetic complications and disease duration with lower body disability. The analyses were controlled for the above covariates and treatment received at baseline. All analyses were performed using the SAS System for Windows (version 8; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The overall prevalence of self-reported DM among non-disabled participants in this sample was 18.9%. Diabetic participants were significantly more likely to report heart attack, hypertension, arthritis, and obesity compared with their nondiabetic counterparts (Table 1). Mean duration of the disease was 11.7 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 9.0 years; 86.5% of diabetic participants were under treatment (59.4% with oral hypoglycemic; 23.1% with insulin, and 4.0% with combined treatment). A significant number reported serious complications: 30.0% reported circulation problems; 32.0% reported eye problems, 8.4% reported kidney problems; and 5.2% reported an amputation (Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Older Mexican Americans Nondisabled at Baseline by Diabetes Mellitus (DM) Status (N = 1835)

| Independent Variables | Total N | DM N (%) | No DM N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1835 | 347 (18.9) | 1488 (81.1) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 1835 | 70.8 ± 5.1 | 71.8 ± 5.6 |

| Sex (Female) | 1005 | 189 (54.5) | 816 (54.8) |

| Heart attack* | 151 | 47 (13.5) | 104 (7.0) |

| Stroke | 53 | 14 (4.0) | 39 (2.6) |

| Hypertension* | 719 | 187 (53.9) | 532 (35.8) |

| Near vision impairment | 155 | 34 (9.8) | 121 (8.1) |

| Distant vision impairment | 74 | 15 (4.3) | 59 (4.0) |

| Arthritis* | 605 | 142 (40.9) | 463 (31.1) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)† | 524 | 115 (33.1) | 409 (27.5) |

| Hip fracture | 27 | 8 (2.3) | 19 (1.3) |

| Cancer | 85 | 22 (6.3) | 63 (4.2) |

| High depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 16) | 320 | 63 (18.2) | 257 (17.3) |

| MMSE score, mean ± SD | 1835 | 26.3 ± 3.5 | 25.9 ± 3.7 |

Notes: p < .0001.

p < .01.

BMI = body mass index; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SD = standard deviation; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Nondisabled Older Mexican Americans With Diabetes Mellitus (N = 347)

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Duration of disease, mean ± standard deviation | 11.7 ± 9.0 |

| Treatment | |

| None | 47 (13.5) |

| Oral hypoglycemic | 206 (59.4) |

| Insulin | 80 (23.1) |

| Oral hypoglycemic + insulin | 14 (4.0) |

| Complications | |

| Eyes | 111 (32.0) |

| Kidney | 29 (8.4) |

| Circulation | 104 (30.0) |

| Amputations | 18 (5.2) |

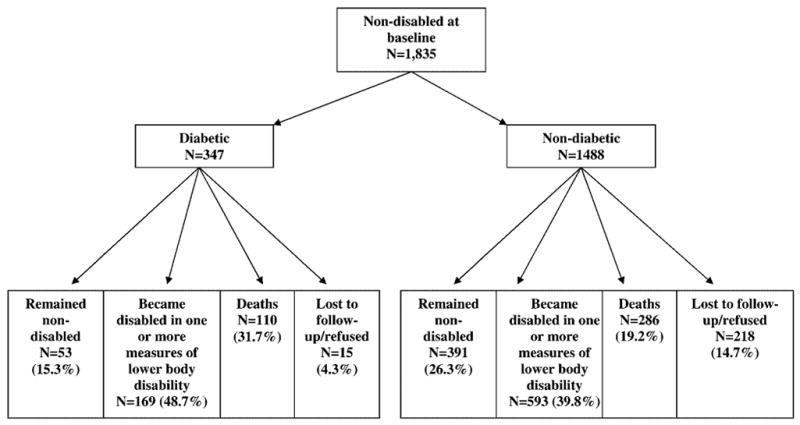

Figure 1 presents the status of the sample at 7-year follow-up among nondisabled participants at baseline. Of the 1488 nondiabetic participants, 391 (26.3%) remained nondisabled and 593 (39.8%) became disabled in one or more lower body disability measures. Of the 347 diabetic participants, 53 (15.3%) remained nondisabled and 169 (48.7%) became disabled in one or more lower body disability measures.

Figure 1.

Status of the sample at 7-year follow-up among nondisabled older Mexican Americans at baseline.

Table 3 presents the results of a multivariable analysis predicting the hazard of any lower body disability during 7 years of follow-up among nondisabled participants at baseline, as a function of DM, controlling for all covariates. Diabetic participants had a higher risk of developing lower body disability over time compared with nondiabetic participants. The hazard ratio (HR) for reporting any lower body ADL limitation was 2.05 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.58–2.67), for limitation in mobility was 1.69 (95% CI, 1.39–2.04), and for walking limitation was 1.46 (95% CI, 1.15–1.85).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis Predicting Hazard of Lower Body Disability Among Nondisabled Older Mexican Americans at Baseline Over a 7-Year Follow-Up (N = 1835)

| Independent Variables | Any Lower ADL Limitation HR (95% CI) | Any Mobility Limitation HR (95% CI) | Walking Limitation HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.05 (1.58–2.67) | 1.69 (1.39–2.04) | 1.46 (1.15–1.85) |

| Age (each 1-y increase) | 1.08 (1.05–1.10) | 1.07 (1.05–1.08) | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) |

| Sex (female vs male) | 1.24 (0.97–1.58) | 1.20 (1.01–1.42) | 1.10 (0.90–1.35) |

| High depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 16) | 1.18 (0.87–1.59) | 1.28 (1.04–1.56) | 1.30 (1.01–1.66) |

| MMSE score (each one-point increase) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) |

| Near vision impairment | 1.10 (0.74–1.64) | 1.20 (0.91–1.58) | 1.17 (0.83–1.65) |

| Distant vision impairment | 1.32 (0.82–2.11) | 1.07 (0.75–1.54) | 1.18 (0.78–1.79) |

| Heart attack | 1.42 (1.00–2.03) | 1.25 (0.96–1.63) | 0.96 (0.68–1.36) |

| Stroke | 0.54 (0.24–1.23) | 0.77 (0.47–1.25) | 0.77 (0.42–1.42) |

| Hypertension | 1.04 (0.82–1.33) | 1.11 (0.94–1.31) | 1.00 (0.82–1.23) |

| Arthritis | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 1.09 (0.85–1.41) | 1.22 (1.03–1.45) | 1.12 (0.91–1.38) |

| Hip fracture | 1.61 (0.75–3.42) | 1.33 (0.75–2.36) | 1.28 (0.63–2.60) |

| Cancer | 0.95 (0.53–1.69) | 1.15 (0.80–1.67) | 1.35 (0.87–2.08) |

Notes: Reference categories are given in parentheses.

BMI = body mass index; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; ADL = Activities of Daily Living; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Table 4 presents the results of a multivariable analysis predicting the hazard of any lower body disability during 7-year follow-up among nondisabled diabetic participants at baseline. Older age and having an amputation were factors associated with an increased risk over time of reporting any lower body ADL limitation and walking limitation. Kidney complication was associated with an increased risk of walking limitation. No interaction effects were found between DM and covariates for lower body disability.

Table 4.

Multivariable Analysis Predicting Hazard of Lower Body Disability Among Nondisabled Diabetic Older Mexican Americans at Baseline Over a 7-Year Follow-Up (N = 347)

| Independent Variables | Any Lower Body ADL Limitation HR (95% CI) | Any Mobility Limitation HR (95% CI) | Walking Limitation HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (each 1-y increase) | 1.08 (1.04–1.13) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) |

| Sex (female vs male) | 1.25 (0.78–2.02) | 1.13 (0.79–1.61) | 1.15 (0.72–1.84) |

| Duration (each 1-y increase) | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) |

| Diabetic complications | |||

| Eyes | 1.05 (0.63–1.75) | 1.12 (0.76–1.63) | 1.14 (0.70–1.85) |

| Kidney | 1.74 (0.81–3.72) | 1.69 (0.94–3.04) | 2.30 (1.05–5.03) |

| Circulation | 1.24 (0.76–2.03) | 1.25 (0.86–1.81) | 0.95 (0.58–1.54) |

| Amputations | 2.30 (1.01–5.25) | 1.50 (0.78–2.88) | 2.46 (1.17–5.20) |

Notes: The above analyses were controlled for heart attack, hypertension, stroke, visual impairment, arthritis, obesity, hip fracture, cancer, Mini-Mental State Examination, high depressive symptoms, and treatment.

Reference categories are given in parentheses.

ADL = Activities of Daily Living; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

This prospective cohort study demonstrates that older Mexican Americans with self-reported DM are at higher risk for decline in lower body function over a 7-year follow-up period. Diabetic participants were twice as likely to report any lower body ADL limitation over time compared with those participants without DM. Also, they were significantly more likely to report any limitations in mobility and walking limitation over time compared with their nondiabetic counterparts. Despite adjustments for prevalent chronic conditions and impairments, the association between DM and incidence of lower body disability remained statistically significant.

Previous research has suggested that the association of DM and the disablement process is multifactorial (14,15). Several mechanisms may explain our findings. First, diabetic participants were significantly more likely to report heart attack, hypertension, and arthritis than were their counterparts. All these factors are well known risk factors for disability in this population (35). Second, microvascular (retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy) and macrovascular (coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease) complications may play an important role in the disablement process. We found that diabetic participants with eye or kidney complications had an increased risk over time of reporting lower body disability. Third, the high incidence of nontraumatic lower extremity amputation in this population (36) may also contribute to disablement process in diabetic participants. We found that those diabetic participants with an amputation had an increased risk of reporting lower body disability over time compared with diabetic participants without an amputation.

This study has some limitations. First, the assessment of DM and its complications was by self-report. Clinical observation may provide a different and more precise diagnosis. However, the self-report approach has been documented to provide reliable information and a good agreement between self-reported DM and DM diagnosed by blood tests (37,38). Second, the assessment of ADL lower body and mobility was also by self-report. Nevertheless, several studies have demonstrated a high concordance between self-reported data and direct observations of ADL performance (39). Assuming that the incidence of lower body disability in participants with undiagnosed DM is higher than that in nondiabetic participants, the bias related to undiagnosed DM would lead to an underestimation of the association between DM and lower body disability. However, we use both a subjective (self-reported ADLs and mobility) and an objective measure (observed 8-foot walk) of walking to assess lower body function.

Conclusion

This study found that older Mexican Americans with DM are at higher risk for development of lower body disability over time than are nondiabetic persons. Attenuation of diabetic chronic complications and those modifiable factors (obesity and depressive symptoms) associated with lower body disability could reduce the impact of the disease at both the individual and societal levels. Additionally, lower body disability should be considered a long-term outcome of DM. Awareness of disability as a potentially modifiable complication and use of culturally appropriate interventions to prevent disability and diabetic complications should become health priorities for older Mexican Americans.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants AG10939, AG017231, and AG1763803 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Raji’s work is supported by the Bureau of Health Professions’ Geriatric Academic Career Award 1 K01 HP 00034-01. Dr. Glenn V. Ostir was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Footnotes

Decision Editor: John E. Morley, MB, BCh

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2003. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/estimates.htm3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: U.S.; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/aag/aag_ddt.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samos LF, Roos BA. Prevention and treatment of diabetes and its complications: diabetes mellitus in older persons. Med Clin North Am. 1982;82:791–804. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, Second Supplement on Aging. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirvensalo M, Rantanen T, Heikkinen E. Mobility difficulties and physical activity as predictors of mortality and loss of independence in the community-living older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Disability in older adults: evidence regarding significance, etiology and risk. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seeman TE, Charpentier PA, Berkman LF, et al. Predicting changes in physical performance in a high-functioning elderly cohort: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M97–M108. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.m97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penninx BW, Ferrucci L, Leveille SG, Rantanen T, Pahor M, Guralnik JM. Lower extremity performance in nondisabled older persons as a predictor of subsequent hospitalization. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2000;54A:M691–M697. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markides KS, Black SA, Ostir GV, Angel RJ, Guralnik JM, Lichtenstein M. Lower body function and mortality in Mexican American elderly people. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2001;56A:M243–M247. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.4.m243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan DM. Long-term complications of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1676–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306103282306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller DK, Lily Lui LY, Perry HM, Kaiser FE, Morley JE. Reported and measured physical functioning in older inner-city diabetic African Americans. J Gerontol. 1999;54:M230–M236. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.5.m230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volpato S, Blaum C, Resnick H, Ferrucci L, Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Comorbidities and impairments explaining the association between diabetes and lower extremity disability. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:678–683. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters EJG, Childs MR, Wunderlich RP, Harkless LB, Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Functional status of persons with diabetes-related lower-extremity amputations. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1799–1804. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregg EW, Williamson DF, Leveille SG, Langlois JA, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Diabetes and physical disability among older U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1272–1277. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Grauw WJC, van de Lisdonk EH, Behr RR, van Gerwen WH, van den Hoogen HJ, van Weel C. The impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on daily functioning. Fam Pract. 1999;16:133–139. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volpato S, Ferrucci L, Blaum C, et al. Progression of lower-extremity disability in older women with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;26:70–75. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregg EW, Mangione CM, Cauley JA, et al. Diabetes and incidence of functional disability in older women. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:61–67. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodríguez-Saldaña J, Morley JE, Reynoso MT, et al. Diabetes mellitus in a subgroup of older Mexican Americans: prevalence, association with cardiovascular risk factors, functional and cognitive impairment, and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:111–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu JH, Haan MN, Liang J, Ghosh D, Gonzalez HM, Herman WH. Diabetes as a predictor of change in functional status among older Mexican Americans: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:314–319. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black SA, Ray LA, Markides KS. The prevalence and health burden of self-reported diabetes in older Mexican Americans: findings from the Hispanic established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:546–552. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.4.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otiniano ME, Du XL, Ottenbacher K, Markides KS. The effect of diabetes combined with stroke on disability, self-rated health, and mortality in older Mexican Americans: results from the Hispanic EPESE. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:725–730. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(02)04941-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA. Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2822–2828. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markides KS, Stroup-Benham CA, Black S, Satish S, Perkowski L, Ostir G. The Health of the Mexican American elderly: selected findings from the Hispanic EPESE. In: Wykle ML, Ford AB, editors. Serving Minority Elders in the 21st Century. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc; 1999. pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branch LG, Katz S, Kniepmann K. A prospective study of functional status among community elders. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:266–268. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. J Gerontol. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostir GV, Markides KS, Black SA, Goodwin JS. Lower body functioning as a predictor of subsequent disability among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53A:M1–M5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.6.m491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS. The CED-S scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK. Screening for depression in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100059010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bird HR, Canino G, Stipec MR, Shrout P. Use of the Mini-Mental State Examination in a probability sample of a Hispanic population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175:731–737. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bray GA. Overweight is risking fate. Definition, classification, prevalence, and risks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;499:14–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb36194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salive M, Guralnik J, Glynn RJ, Christen W, Wallace RB, Ostfeld AM. Association of visual impairment with mobility and physical function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:287–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markides KS, Perkowski LP, Stroup-Benham CA, Lichtenstein M, Goodwin JS. Impact of selected medical conditions on lower-extremity function in Mexican American elderly. Ethn Dis. 1998;8:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otiniano ME, Du X, Ottenbacher K, Black SA, Markides KS. Lower extremity amputations in diabetic Mexican American elders. incidence, prevalence and correlates. J Diabetes Complications. 2000;17:235–245. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Midthjell K, Holmen J, Bjorndal A, Lund-Larsen G. Is questionnaire information valid in the study of chronic disease such as diabetes? The Nord-Trondelg diabetes study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46:537–542. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.5.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaye SA, Folsom AR, Sprafka JM, Prineas RJ, Wallace RB. Increased incidence of diabetes mellitus in relation to abdominal obesity in older women. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:329–334. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90044-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reuben DB, Siu AL, Kimpau S. The predictive validity of self-reported and performance-based measures of function and health. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1992;47:M106–M110. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.4.m106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]