Abstract

These studies examined the effects of increased dietary sodium on expression of Fos, the protein product of c-fos, in forebrain structures in the rat following intravenous infusion with angiotensin II (AngII). Animals were provided with either tap water (Tap) or isotonic saline solution (Iso) as their sole drinking fluid for 3–5 weeks prior to testing. Rats were then implanted with catheters in a femoral artery and vein. The following day the conscious, unrestrained animals received iv infusion of either isotonic saline (Veh), AngII, or phenylephrine (Phen) for two hrs. Blood pressure and heart rate were monitored continuously throughout the procedure. Brains were subsequently processed for evaluation of Fos-like immunoreactivity (Fos-Li IR) in the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT), the subfornical organ (SFO), and the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO). Fos-Li IR was significantly increased in the SFO and OVLT of animals consuming both Tap and Iso following AngII, but not Phen, compared to Veh infusions. Furthermore, Fos-Li IR in the MnPO was increased following AngII infusion in rats consuming a high sodium diet, but not in animals drinking Tap. These data suggest that increased dietary sodium sensitizes the MnPO neurons to excitatory input from brain areas responding to circulating AngII.

Keywords: Blood pressure, sympathetic nervous system, hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Circulating angiotensin II (AngII) produces a number of effects by activation of the central nervous system (CNS), including initiation of thirst, vasopressin release, and increased blood pressure. Previous studies have demonstrated that the pressor response induced by systemic infusion of AngII is initially mediated primarily by the direct, peripheral vasoconstrictor effects of the peptide, with relatively little contribution from the sympathetic nervous system (SymNS), due to suppression by baroreceptor activation (Xu and Sved, 2001). However, during continuous infusion, AngII-induced SymNS activation makes a progressively larger contribution to the increase in blood pressure (Bealer, 2003; Li et al., 1996). Furthermore, we previously found that animals ingesting increased dietary sodium demonstrate a more rapid activation of the SymNS component of the pressor response during chronic iv AngII administration (Bealer, 2003). These data indicate that high sodium ingestion alters the CNS processing of signals induced by circulating AngII. Specifically, these findings are consistent with the proposal that increased dietary sodium sensitizes CNS centers to the sympathoexcitatory effects of circulating AngII. However, these central sites have not been identified.

Structures located along the lamina terminalis, the rostral border of the third cerebral ventricle, are critical for activation of the neuroaxis by blood-borne AngII. Two circumventricular organs, the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT) and the subfornical organ (SFO), which respond directly to circulating AngII (Johnson et al., 1996; Johnson and Thunhorst, 1997; McKinley et al., 1996), and the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO), which receives afferent input from the SFO and OVLT (Lind and Johnson, 1982; Lind et al., 1984), constitute a local circuit within the lamina terminalis for processing information derived from humoral inputs to regulate body fluid balance and cardiovascular responses (Johnson et al., 1996; Johnson and Gross, 1993; Zardetto-Smith et al., 1993). This proposal has been supported by a number of studies demonstrating that circulating AngII stimulates each of these sites independently of baroreceptor activation (Badoer and McKinley, 1997; McKinley et al., 1992; McKinley et al., 1995; Potts et al., 1999), and studies demonstrating that lesions of the entire lamina terminalis, or individual components of the circuit, abolish a variety of behavioral and physiological responses to circulating AngII (Bellin et al., 1987; Bellin et al., 1988; Cunningham et al., 1992; Johnson et al., 1996; Jones, 1988; McKinley et al., 1996).

Since this circuit is critical for behavioral and physiological responses, including activation of the SymNS during systemic AngII infusion, we proposed that increased sodium ingestion would alter the sensitivity of these brain sites to the excitatory effects of circulating AngII. To test this proposal, we evaluated neuronal activation of these structures along the lamina terminalis by measuring immunohistochemical labeling of Fos, the protein product of the immediate early gene c-fos, in the OVLT, SFO, and MnPO of animals consuming normal or high sodium diet following iv administration of AngII.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 200 and 250 g were obtained from a commercial supplier (Harlan), and housed two to three per cage in plexiglass cages. Animals were allowed access to standard laboratory rat chow and drinking solution ad libitum. Room temperature was maintained at 23o C and room lights were on for 12 h/day. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animals Care and Use Committee at the University of Utah.

Sodium Ingestion

Prior to testing, animals were provided with either tap water (Tap) or 0.9% saline (Iso) as their sole drinking solution for 3–5 weeks. Animals had ad libitum access to drinking fluid and standard rat chow (Harlan 8640, 0.4% sodium content) until tested.

Surgery

In preparation for testing, animals were anesthetized with 300 mg/kg 2,2,2 tribromoethanol (Avertin, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and polyethylene catheters (40 mm PE-10 cemented into PE-50), filled with heparinized (50 U/ml) isotonic saline, were implanted into a femoral artery and femoral vein. Catheters were externalized between the scapulae and sealed. Following surgery, rats were returned to their home cages and allowed to recover from the anesthetic and tested the next day.

Protocol

On the day of the experiment, the arterial catheter was connected to a pressure transducer and MacLab data acquisition system for continuous monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate. The femoral vein catheter was connected to a remote syringe filled with either isotonic saline vehicle (Veh; Tap, n=5; Iso, n=6), phenylephrine (Phen, 180 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO; Tap, n=4; Iso, n=5), or AngII (500 ng/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO; Tap, n=6, Iso, n=6).

The animals were then left undisturbed for 45–60 min. Following equilibration, iv infusions were initiated and maintained at a rate of 40 ul/min/kg for a period of 2 hr. Separate groups of control (Cont; Tap, n=3; Iso, n=3) animals were treated similarly, except they received no infusion.

Following the infusion period, rats were deeply anesthetized with Avertin and transcardially perfused with 250–300 ml ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) followed by 250–300 ml paraformaldehyde. Brains were extracted and placed in vials containing 30% sucrose/4% paraformaldehyde for 3 hr, and then transferred to vials containing 30% sucrose.

Fos-immunoreactivity

Brains were subsequently processed for Fos-like immunoreactivity (Fos-Li IR) with procedures routinely used in our laboratory (Bealer and Metcalf, 2005). Briefly, brains were blocked, frozen on dry ice, and 50-μm-thick sections were collected from rostral to the anterior commissure through the lamina terminalis. Free floating sections were placed in PBS+0.2% Triton-X (PBS-Triton). Sections were incubated in 0.5% sodium borohydride for 20 min then rinsed three times with PBS-Triton. The sections were then incubated in 0.3% H2O2 for 20 min and rinsed with PBS-Triton. The blocking step included incubating sections in 1.5% goat serum (in PBS-Triton) for 1 hr. Immediately after this incubation, the goat serum was removed and tissue was incubated in c-fos primary antibody (Rabbit polyclonal IgG, 1;5000, 0.02 μl/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Santa Cruz, CA) for 36–48 hr at 4 o C. This antibody cross reacts with other Fos family members including FosB, Fra1, and Fra2. Sections were then rinsed with PBS-Triton and incubated in biotinylated antibody (5 μl/ml, Vector ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hr at room temperature, then rinsed with PBS-Triton. Next sections were incubated in ABC reagent (20ul/ml avidin DH+20 μl/ml biotinylated enzyme, Vector ABC kit) for 1 hr at room temperature. Slices were then exposed to 3’3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Fast-Dab; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for approximately 2–5 min. Finally, the tissue was rinsed in PBS and placed on pre-treated slides and allowed to dry overnight before coverslipping (Cytoseal 60, Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI).

As a control for non-specific staining of cells, brains from a separate group of rats were treated similarly, except incubation with the primary c-fos antibody was omitted. There was no reaction product in these tissues following processing.

Quantification of Fos-Li IR

A Leitz light microscope was used to examine tissue sections using light field microscopy, and images captured with a Nikon Coolpix 995 camera. These digital images were then analyzed using NIH Image software. Neurons were considered to contain Fos-Li IR and were counted if their nuclei appeared as dark, circular structures with clearly defined edges with the reaction product clearly visible above background. Counting was done by observers blind to the experimental conditions of the animals.

The MnPO, SFO, and OVLT were analyzed. Two or three sections of each brain area from every rat were counted. The entire region of interest was outlined and then quantified with NIH Image software. Fos-Li IR cells were counted in each section, and data were recorded as mean counts/1000 μm2/section.

Statistics

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Experimental effects were determined using a two-factor ANOVA, and differences between individual groups were evaluated using a Fisher LSD a posteriori analysis. A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

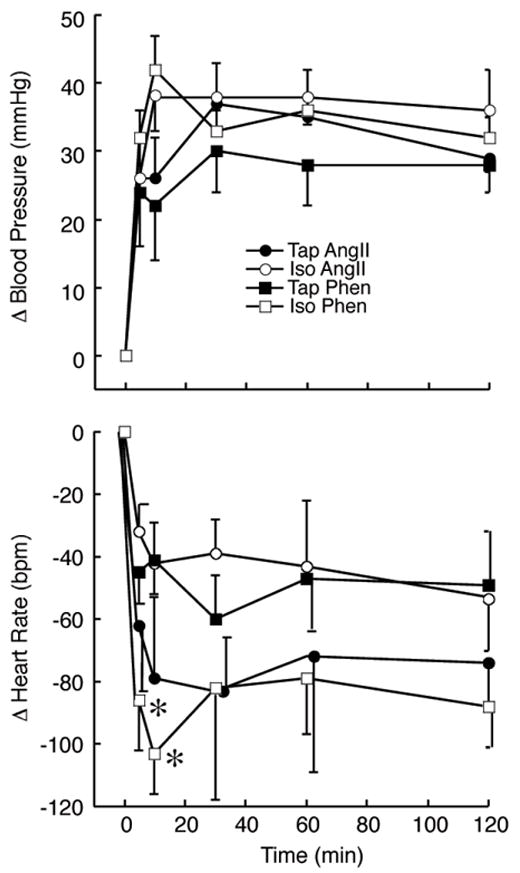

RESULTS

The duration of saline consumption was equally distributed across the experimental period (3–5 weeks) for Iso rats, and there was no relationship between the period of isotonic saline ingestion and blood pressure, heart rate, or Fos-Li IR. Furthermore, at the time of testing, mean arterial blood pressure was not significantly different between Tap (107±3 mmHg) and Iso (113±3 mmHg) rats prior to the infusion period. Finally, the increase in blood pressure during the infusion period was equivalent for both experimental groups infused with AngII or Phen (Fig. 1, Top Panel). The blood pressure in Cont rats and in animals infused with Veh did not change during the infusion period. (Data not shown).

Figure 1.

Change in blood pressure (Top Panel) and heart rate (bottom panel) for animals consuming isotonic saline (Iso; open symbols) or tap water (Tap; closed symbols) which received iv infusion of angiotensin II (AngII; circles) or phenylephrine (Phen; squares). *p<0.05 Tap Phen vs. Iso Phen.

Basal heart rate tended to be lower in animals consuming Iso (381±10 bpm) than in rats ingesting Tap (405±15 bpm), although this difference was not statistically significant. In addition, the initial (5–15 min) bradycardia observed during infusion of Phen was greater in Iso animals than in Tap rats. However, the fall in heart rate associated with AngII infusion was equivalent throughout the observation period between groups (Fig. 1, Bottom Panel).

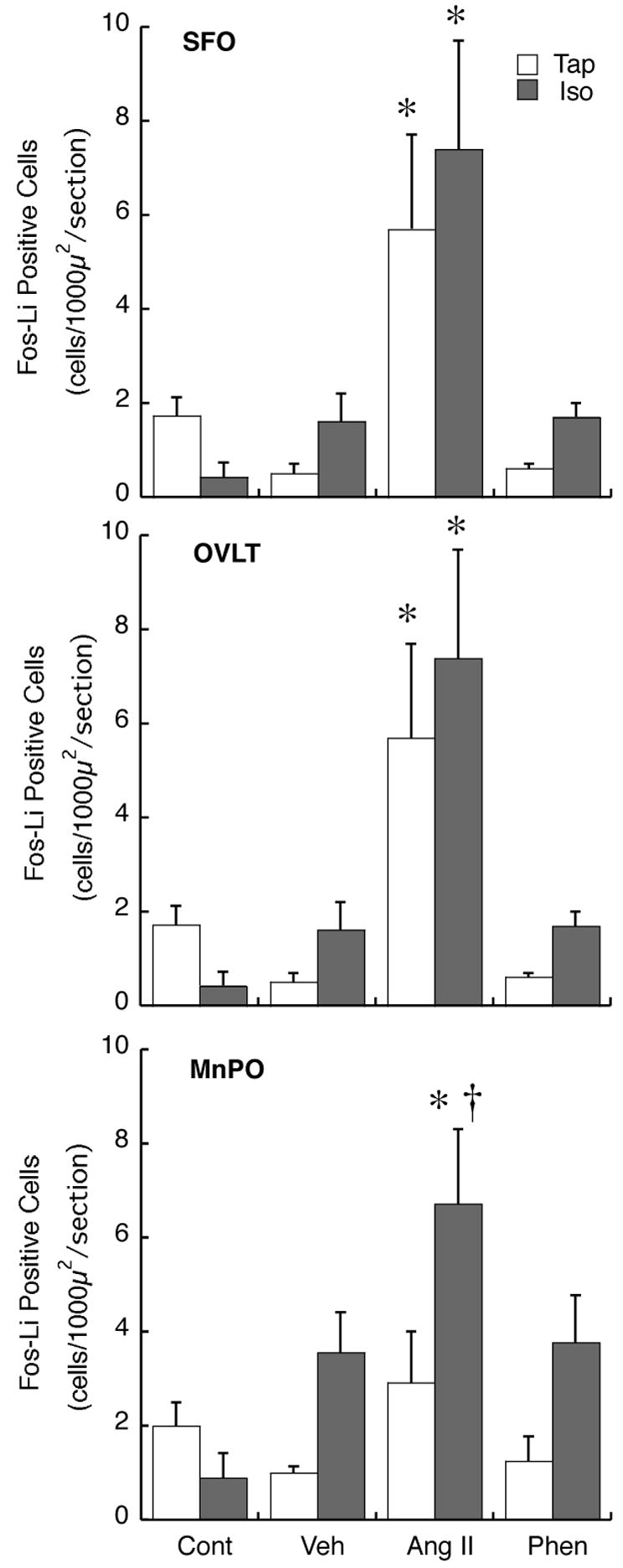

Fig. 2 shows representative photomicrographs of the SFO obtained from rats administered iv Veh, AngII, or Phen. A summary of total Fos-Li IR in the SFO is presented in Fig. 5. Fos-Li IR in was similar between Cont groups, and Tap and Iso rats infused with Veh or Phen. Furthermore, AngII infusion resulted in a similar significant increase in Fos-Li IR in the SFO of both groups of experimental animals.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of coronal brain sections through the subfornical organ from animals which received iv infusion of isotonic saline (Veh), angiotensin II (AngII) or phenylephrine (Phen), and were consuming either tap water (Tap) or isotonic saline (Iso). Abbreviations: hc, commissure of the hippocampus; sfo, subfornical organ, bar= 200 μm.

Figure 5.

Summary of the number of cells demonstrating Fos-Li IR in the SFO, OVLT, and MnPO following no treatment (Cont), or iv infusion of isotonic saline (Veh), angiotensin II (AngII), or phenylephrine (Phen) * p< 0.05 compared to Veh; †p<0.01 compared to Tap, same infusion solution.

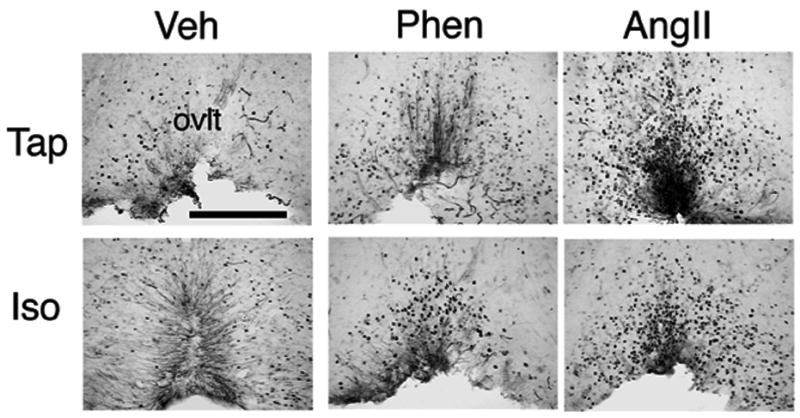

A similar relationship was observed in Fos-Li IR in the OVLT (Fig. 3; Summarized data in Fig. 5). Iso ingestion did not alter basal Fos-LI IR in this structure (Cont), or following Veh or Phen infusion. Furthermore, similar to the SFO, AngII administration during the infusion period resulted in similar increases in Fos-Li IR in the OVLT of both Iso and Tap rats.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of coronal brain sections through the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis from animals which received iv infusion of isotonic saline (Veh), angiotensin II (AngII) or phenylephrine (Phen), and were consuming either tap water (Tap) or isotonic saline (Iso). Abbreviations: ovlt, organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, bar= 200μm.

The effects of high sodium ingestion on Fos-Li IR in the MnPO are shown in Fig. 4 and summarized in Fig. 5. Similar to the SFO and the OVLT, there were no differences in basal Fos-Li IR between Iso and Tap rats in this structure. Infusion of Veh did not significantly alter Fos-Li IR in either group. Although Veh-infused Iso animals tended to show greater Fos-Li IR than Cont-Iso and Veh-infused Tap animals, these differences were not statistically significant (p=0.07, p=0.08, respectively). Similarly, Phen administration did not significantly change Fos-Li IR in the MnPO in either Tap or Iso rats compared to Veh infusion. Iso rats infused with Phen tended to have increased Fos-Li IR compared to Phen-infused Tap rats, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.07). However, infusion of AngII produced differential effects on neuronal activation in the MnPO in Iso compared to Tap rats. In Tap animals, AngII infusion did not alter Fos-Li IR. In distinction, Iso rats infused with AngII demonstrated significantly increased Fos-Li IR in the MnPO compared to both Veh-infused Iso animals, and AngII-infused Tap rats.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of coronal brain sections through the median preoptic nucleus from animals which received iv infusion of isotonic saline (Veh), angiotensin II (AngII) or phenylephrine (Phen), and were consuming either tap water (Tap) or isotonic saline (Iso). Abbreviations: ac, anterior commissure; bar= 200μm.

DISCUSSION

The present studies investigated the effects of increased dietary sodium on neuronal activation of the SFO, OVLT, and MnPO in response to iv infusion of AngII by evaluating Fos-Li IR. While neuronal activation of the SFO and OVLT were equivalent between animals consuming Tap and Iso in all infusion conditions, Fos-Li IR was selectively increased in response to AngII infusion in the MnPO of animals consuming higher dietary sodium.

The SFO, OVLT, and MnPO of the lamina terminalis comprise a forebrain neuronal circuit regulating body fluid balance and cardiovascular responses to circulating hormones and systemic osmolality (Johnson et al., 1996; McKinley et al., 1996; Zardetto-Smith et al., 1993). Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of the lamina terminalis as a whole, as well as individual components and neural connections between these sites in CNS-mediated responses to systemic AngII (Bellin et al., 1987; Cunningham and Johnson, 1991; Cunningham et al., 1991; Lind and Johnson, 1982; Mangiapane et al., 1983). Further support for the lamina terminalis in mediating central effects of circulating AngII comes from studies using Fos-Li IR as an indication of neuronal activation. These reports have consistently demonstrated that Fos-Li IR is increased in the SFO and OVLT by circulating AngII (McKinley et al., 1992; McKinley et al., 1995; Potts et al., 1999; Rowland et al., 1996; Rowland et al., 1994). However, results on the effects of systemic AngII on Fos-Li IR in the MnPO have been equivocal. While some studies found increased MnPO Fos-Li IR in rabbits (Potts et al., 1999) and rats (Rowland et al., 1996; Rowland et al., 1994) after systemic AngII, other reports found only weak Fos-Li IR in the MnPO of rats (McKinley et al., 1995). Results from the present experiments agree with this latter report (McKinley et al., 1995), as we found that systemic AngII did not produce significant Fos-Li IR in the MnPO in animals consuming Tap water. However, our experiments extend earlier results by demonstrating that Fos-Li IR was enhanced during AngII infusion in animals consuming Iso. These data suggest that a high sodium diet sensitizes the neurons in the MnPO to the excitatory input evoked by blood-borne AngII.

In addition to the OVLT and SFO, circulating AngII also stimulates neurons in a circumventricular organ located in the medulla, the area postrema, to alter SymNS and cardiovascular function (Johnson et al., 1996; Johnson and Thunhorst, 1997). The MnPO receives afferent input from medullary cardiovascular sites innervated by the area postrema (Saper and Levisohn, 1983; Tanaka et al., 1992). Consequently, the enhanced effects of systemic AngII on MnPO neurons may be mediated by increased sensitivity and/or afferent input to MnPO neurons from the SFO, OVLT, and/or medullary brain sites stimulated by AngII action on the area postrema. The mechanism(s) regulating enhanced MnPO neuronal activation by circulating AngII is not currently understood.

Regardless of the specific mechanism which enhances responses in the MnPO, results from the present studies suggest an anatomical basis for previous findings on the relationship between dietary sodium, circulating AngII, and SymNS activation. Systemic AngII increases blood pressure initially by direct action on receptors located on vascular smooth muscle. Although there is also a central action to activate the SymNS (Li et al., 1996), it is initially masked by baroreceptor activation (Xu and Sved, 2001). Subsequently, during chronic infusion of AngII, the systemic component of the AngII receptor stimulation decreases and the pressor response is increasingly dependent upon SymNS activation (Bealer, 2003; Li et al., 1996). We previously found that the SymNS component of the AngII-induced pressor response returns more quickly in animals consuming increased dietary sodium (Bealer, 2003). The present experiments suggest that this may be due to sensitization of MnPO neurons to the stimulatory effects of circulating AngII at the SFO, OVLT, and/or area postrema, and subsequent activation of the SymNS. This proposal is consistent with recent studies demonstrating a population of neurons in the MnPO which respond to circulating AngII, project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, and are associated with SymNS activation (Stocker and Toney, 2005).

Increased dietary sodium represents a risk factor for the development, maintenance, and exacerbation of hypertension. However, the mechanisms of this effect have not been completely elucidated (Campese, 1994). One mechanism through which dietary sodium may predispose toward chronically increased arterial pressure is by sensitizing central SymNS sites to the excitatory effects of pressor stimuli (Ito et al., 1999; Pawloski-Dahm and Gordon, 1993). The present experiments have presented evidence that a central circuitry involved in activation of the SymNS to circulating AngII is sensitized to the sympathoexcitatory effects of circulating AngII. Long term activation of the SymNS by AngII could be a major contributing factor to development and maintenance of hypertension (Fink, 1997). Therefore, chronically enhanced sensitivity of the SFO/OVLT/area postrema/MnPO circuit to the sympathoexcitatory effects of AngII is a potential mechanism through which increased dietary sodium may contribute to hypertension.

Previous findings demonstrate that increased dietary sodium can enhance baroreflex responses (Bealer, 2005; Huang and Leenen, 1994). Similarly, in the present studies, the initial fall in heart rate during Phen-induced pressor response was greater in Iso animals compared to Tap rats (Fig. 1). In addition, we have previously shown that the bradycardia associated with systemic AngII infusion was also potentiated by high sodium diet (Bealer, 2003). However, in the present study, the falls in heart rate of Iso and Tap rats infused with AngII were equivalent. The reason for these differences in the relative heart rate responses during AngII infusion is unknown.

The increase of Fos-Li IR in the MnPO appears specific to AngII infusion, and not the resulting increase in blood pressure, as similar increases in pressure with Phen did not significantly increase Fos-Li IR in the MnPO in either experimental condition. This is similar to earlier reports showing that Fos-Li IR in the MnPO does not increase during Phen infusion (McKinley et al., 1992). This results also supports the view that increased MnPO sensitivity to afferent input from blood pressure sensitive sites in the medulla was not enhanced by Iso ingestion (McKitrick et al., 1992; Saper and Levisohn, 1983; Saper et al., 1983), and supports the proposition that the increased Fos-Li IR in the MnPO was due to increased sensitivity to AngII afferent input from the SFO, OVLT, and/or the area postrema.

Although not significantly increased, Fos-Li IR in the MnPO of Iso animals infused with Veh and with Phen tended to be elevated compared to Cont-Iso rats. These data suggest that high sodium diet may sensitize animals to stress associated with the experimental procedures, which has been shown to increase Fos-Li IR in SymNS centers (Kantzides and Badoer, 2003). This interpretation is consistent with the proposal that increased dietary sodium sensitizes the SymNS not only to central (Ito et al., 1999; Pawloski-Dahm and Gordon, 1993) and peripheral (Bealer, 2003) pressor stimuli, but also to environmental conditions which may increase stress and blood pressure. However, since Fos-Li IR in the MnPO induced by AngII infusion in Iso animals was significantly greater than following Veh administration, it is unlikely that a potential differential stress response to the infusion conditions accounted for the enhanced neuronal activation in Iso rats during AngII administration.

The mechanism through which increased dietary sodium enhances Fos-Li IR in the MnPO, but not the SFO or OVLT following AngII infusion is unknown. Differential activation in these brain sites may be related to changes in AngII receptor binding in the MnPO, as AT1 receptor binding density increases in this brain site, but not the SFO or the OVLT, in normotensive rats placed on high salt diet for 4 weeks (Wang et al., 2003) Direct effects on CNS structures in response to increased plasma osmolality in the present experiments appear unlikely. Although not measured in the present study, previous experiments have demonstrated that plasma osmolality is not increased in rats consuming isotonic saline for three weeks (Bealer, 2005; Bealer and Metcalf, 2005). However, chronic excitation of gastric and/or hepatoportal sodium or osmoreceptors induced by long term ingestion of isotonic saline acting on the MnPO through the area postrema and/or nucleus tractus solitarius (Carlson et al., 1998; Carlson and Osborn, 1998) could enhance responses of the MnPO to afferent input without a concurrent increase in plasma osmolality and/or sodium concentration. Finally, changes in MnPO responses may be due to long term suppression of circulating AngII induced by high salt intake. Defining the precise mechanism through which increased dietary sodium alters reactivity of MnPO neurons to circulating AngII, as well as reactivity of other sympathetic nervous system centers to pressor stimuli (Ito et al., 1999; Pawloski-Dahm and Gordon, 1993) will require further inquiry.

Previous studies have reported specific distributions of neuronal activation induced by iv AngII in the SFO and OVLT. For example, some investigators found Fos-Li IR primarily in the annular region of the OVLT (McKinley et al., 1992), and the posterior portion of the SFO (Rowland et al., 1994). However, these patterns of neuronal activation are not universally observed. Other studies, some from these laboratories, find Fos-Li IR concentrated in the inner core of the SFO (McKinley et al., 1998) and lateral regions of the OVLT (McKinley et al., 1998), or equally distributed throughout one or both of these circumventricular organs (McKinley et al., 1992; Potts et al., 1999). In agreement with some of the earlier reports (McKinley et al., 1998; Potts et al., 1999), we found an even distribution of Fos-Li IR across the SFO and OVLT in both TAP and Iso rats (McKinley et al., 1998). This may have resulted from the relatively high dose of AngII used in these studies, as the specific pattern of neuronal activation in circumventricular organs appears to depend upon the infused concentration of AngII (McKinley et al., 1998).

Similarly, the dose of AngII used in the present experiments may have maximally stimulated neurons in the SFO and OVLT, and consequently prevented detection of differences in FOS-Li IR in these structures between Tap and Iso rats. It is possible that utilization of a smaller concentration of AngII may result in enhanced activation of SFO and OVLT neurons in Iso animals, similar to that noted in the MnPO. However, even with the potential of maximal stimulation of SFO and OVLT neurons, we observed enhanced activation of neurons in the MnPO of Iso rats.

In our protocol, animals typically ingest approximately 40–50 mls of isotonic saline per day (Bealer, 2003). Along with normal food consumption, this is equivalent to a 2.5–3 fold increase in daily sodium ingestion. Although not as great as is often used to investigate the cardiovascular effects of high sodium diets (Huang and Leenen, 1992; Ise et al., 1998; Ito et al., 1999), it represents a significant increase in daily sodium consumption.

In the present experiments, we evaluated Fos-Li IR only in the ventral portion of the MnPO. However, neuronal activation in the dorsal and ventral aspects of the MnPO to AngII have always been qualitatively similar (Potts et al., 1999; Rowland et al., 1996; Rowland et al., 1994). Consequently, it is probable that the changes we observed in the ventral portion of the MnPO also occurred throughout this brain structure.

In summary, these experiments have demonstrated that ingesting a high sodium diet alters activation of a CNS circuit which responds to circulating AngII and mediates activation of the SymNS. Specifically, Fos LI IR in the MnPO was significantly enhanced during iv AngII administration in animals consuming increased dietary sodium, while neural activations in the SFO and OVLT were comparable between experimental groups. These data suggest that enhanced sodium ingestion sensitizes MnPO neurons to input from circumventricular organs sensing blood-borne AngII. These findings extend earlier results showing that dietary sodium sensitizes central sympathoexcitatory centers to the stimulatory effects of pressor agents. This could represent a mechanism by which dietary sodium contributes to SymNS tone, and consequently alters baroreflex responses and contributes to hypertension.

Acknowledgments

The authors with to acknowledge the expertise technical assistance of Natalie Knotts. These studies were supported by USPHS grant HL 67722.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Badoer E, McKinley MJ. Effect of intravenous angiotensin II on fos distribution and drinking behavior in rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1515–R1524. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.5.R1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bealer SL. Increased dietary sodium alters neural control of blood pressure during intravenous angiotensin II infusion. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:H559–H565. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00628.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bealer SL. Increased dietary sodium inhibits baroreflex-induced bradycardia during acute sodium loading. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:R1211–R1219. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00244.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bealer SL, Metcalf CS. Increased dietary sodium enhances activation of neurons in the medullary cardiovascular pathway during acute sodium loading in the rat. Auton Neurosci. 2005;117:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellin SI, Landas SK, Johnson AK. Localized injections of 6-hydroxydopamine into lamina terminalis associated structures: Effects on experimentally induced drinking and pressor responses. Br Res. 1987;416:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91498-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellin SI, Landas SK, Johnson AK. Selective catecholamine depletion of structures along the ventral lamina terminalis: Effects on experimentally-induced drinking and pressor responses. Br Res. 1988;456:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campese VM. Salt sensitivity in hypertension: Renal and cardiovascular implications. Hypertension. 1994;23:531–550. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SH, Collister JP, Osborn JW. The area postrema modulates hypothalamic fos responses to intragastric hypertonic saline in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1921–R1927. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SH, Osborn JW. Splanchnic and vagal denervation attenuate central fos but not avp responses to intragastric salt in rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R1243–R1252. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.5.R1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JT, Beltz T, Johnson RF, Johnson AK. The effects of ibotenate lesions of the median preoptic nucleus on experimentally-induced and circadian drinking behavior in rats. Brain Res. 1992;580:325–330. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90961-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JT, Johnson AK. The effects of central norepinephrine infusions on drinking behavior induced by angiotensin after 6-hydroxydopamine injections into the anteroventral region of the third ventricle (av3v) Brain Res. 1991;558:112–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90724-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JT, Sullivan MJ, Edwards GL, Farinpour R, Beltz TG, Johnson AK. Dissociation of experimentally induced drinking behavior by ibotenate injection into the median preoptic nucleus. Brain Res. 1991;554:153–158. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90183-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink GD. Long-term sympatho-excitatory effect of angiotensin II: A mechanisms of spontaneous and renovascular hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997;24:91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BS, Leenen FHH. Dietary na, age, and baroreflex control of heart rate and renal sympathetic nerve activity in rats. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1441–H1448. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.5.H1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BS, Leenen FHH. Dietary na and baroreflex modulation of blood pressure and rsna in normotensive vs. Spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H496–H502. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.2.H496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ise T, Kobayashi K, Biller W, Haberle DA. Sodium balance and blood pressure response to salt ingestion in uninephrectomized rats. Kidney Intl Suppl. 1998;67:S245–S249. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Gordon FJ, Sved AF. Dietary salt intake alters cardiovascular responses evoked from the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1600–R1607. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.6.R1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AK, Cunningham ET, Thunhorst RL. Integrative role of the lamina terminalis in the regulation of cardiovascular and body fluid homeostasis. Clin Exp Pharmacol and Physiol. 1996;23:183–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AK, Gross PM. Sensory circumventricular organs and brain homeostatic pathways. FASEB Journal. 1993;7:678–686. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.8.8500693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AK, Thunhorst RL. The neuroendocrinology of thirst and salt appetite: Visceral sensory signals and mechanisms of central integration. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1997;18:292–353. doi: 10.1006/frne.1997.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL. Kainic acid lesions of the median preoptic nucleus: Effects on angiotensin II induced drinking and pressor responses in the conscious rat. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1988;66:1082–1086. doi: 10.1139/y88-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantzides A, Badoer E. Fos, rvlm-projecting neurons, and spinaly projecting neurons in the pvn following hypertonic saline infurion. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:R945–R953. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00536.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Dale WE, Hasser EM, Blaine EH. Acute and chronic angiotensin hypertension: Neural and nonneural components, time course, and dose dependency. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R200–R207. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.1.R200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind RW, Johnson AK. Subfornical organ-median preoptic connections and drinking and pressor responses to angiotensin II. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1043–1051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-08-01043.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind RW, Swanson LW, Ganten D. Angiotensin II immunoreactivity in the central neural afferents and efferents of the subfornical organ of the rat. Brain Res. 1984;321:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiapane ML, Thrasher TN, Keil LC, Simpson JB, Ganong WF. Deficits in drinking and vasopressin secretion after lesions of the nucleus medianus. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;37:73–77. doi: 10.1159/000123518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Allen AM, Burns P, Colvill LM, Oldfield BJ. Interaction of circulating hormones with the brain: The roles of the subfornical organ and the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. Clin Exp Pharmacol and Physiol. 1998;25:S61–S67. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Badoer E, Oldfield BJ. Intravenous angiotensin II induces fos-immunoreactivity in circumventricular organs of the lamina terminalis. Brain Res. 1992;594:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Badoer E, Vivas L, Oldfield BJ. Comparison of c-fos expression in the lamina terminalis of conscious rats after intravenous or intracerebroventricular angiotensin. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Pennington GL, Oldfield BJ. Anteroventral wall of the third ventricle and dorsal lamina terminalis: Headquarters for control of body fluid homeostasis? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKitrick DJ, Krufoff TL, Calaresu FR. Expression of c-fos protein in rat brain after electrical stimulation of the aortic depressor nerve. Brain Res. 1992;599:215–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90394-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawloski-Dahm CM, Gordon FJ. Increased dietary salt sensitizes vasomotor neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Hypertension. 1993;22:929–933. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts PD, Hirooka Y, Dampney RAL. Activation of brain neurons by circulating angiotensin II: Direct effects and baroreceptor-mediated secondary effects. Neuroscience. 1999;90:581–594. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00572-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland NE, Fregly MJ, Li BH, Han L. Angiotensin-related induction of immediate early genes in rat brain. Regul Pept. 1996;66:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(96)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland NE, Li BH, Rozelle AK, Fregly MJ, M G, Smith GC. Localization of changes in immediate early genes in brain in relation to hydromineral balance: Intravenous angioteinsin II. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33:427–436. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Levisohn D. Afferent connections of the median preoptic nucleus in the rat: Anatomical evidence for a cardiovascular integrative mechanism in the anteroventral third ventricular (av3v) region. Brain Res. 1983;288:21–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Reis DJ, Joh T. Medullary catecholamine inputs to the anteroventral third ventricular cardiovascular regulatory region in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1983;42:285–291. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker SD, Toney GM. Median preoptic neurones projecting to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus respond to osmotic, circulating ang II and baroreceptor input in the rat. J Physiol. 2005;568:599–615. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Nishimura J, Kimura F, Nomura M. Noradrenergic excitatory inputs to median preoptic neurons in rats. Neuroreport. 1992;3:946–948. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199210000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JM, Veerasingham SJ, Tan J, Leenen FHH. Effects of high salt intake on brain AT1 receptor densities in dahl rats. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:H1949–H1955. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00744.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Sved AF. Acute sympathoexcitatory action of angiotensin II in conscious baroreceptor-denervated rats. Am J Physiol. 2001;283:R451–R459. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00648.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zardetto-Smith AM, Thunhorst RL, Cicha MZ, Johnson AK. Afferent signaling and forebrain mechanisms in the behavioral control of extracellular fluid volume. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;689:161–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb55545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]