Abstract

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is a unique lipoprotein that has emerged as an independent risk factor for developing vascular disease. Plasma Lp(a) levels above the common cut-off level of 300 mg/L place individuals at risk of developing heart disease particularly if combined with other lipid and thrombogenic risk factors. Studies in humans have shown Lp(a) levels to be hugely variable and under strict genetic control, largely by the apolipoprotein(a) [apo(a)] gene. In general, Lp(a) levels have proven difficult to manipulate, although some factors have been identified that can influence levels. Research has shown that Lp(a) has a high affinity for the arterial wall and displays many athero-thrombogenic properties. While a definite function for Lp(a) has not been identified, the last two decades of research have provided much information on the biology and clinical importance of Lp(a).

Introduction

Lp(a) was first identified and classified as a “low density lipoprotein variant” over 40 years ago. Similar to low-density lipoprotein (LDL), but containing an additional protein, apo(a), Lp(a) has proven to be pathogenic in nature and involved in the development of coronary heart disease (CHD). Lp(a) has an unusual species distribution being present only in primates and hedgehogs. This makes animal models for the study of Lp(a) metabolism and pathogenicity scarce, although both transgenic rabbit and mouse models have recently been developed. To date, the only major influence on Lp(a) levels is a size polymorphism in the apo(a) gene. Traditional lipoprotein-lowering drugs do not significantly alter Lp(a) levels. This review highlights the latest findings on Lp(a) including new insights into its assembly, pathogenicity and growing clinical importance as a CHD risk factor. Factors affecting plasma Lp(a) levels and new possibilities for Lp(a)-lowering interventions will also be discussed.

Lp(a) Structure

Lp(a) was discovered in human serum in 1963 by Kåre Berg during a study of variation in LDL antigenicity.1 Further characterisation of Lp(a) showed it to consist of a LDL covalently bound to a unique protein called apo(a).2 Apo(a) is a homologue of plasminogen, containing multiple copies of plasminogen kringle 4, a single copy of plasminogen kringle 5, and an inactive protease domain.3 Past studies have shown that the number of kringle 4 (KIV) domains can vary from 12 to 51 giving rise to 34 different-sized apo(a) isoforms.4 Furthermore, within the repeated KIV domain exists 10 distinct types (KIV types 1–10) each present in single copy except for KIV type 2 which exists in varying number.3

Reducing agents were shown to dissociate apo(a) from LDL pointing to the existence of a disulphide linkage between apo(a) and the apolipoprotein (apo) B100 moiety of the LDL molecule.5 Indeed, mutagenesis studies have established that a disulphide bond exists between apo(a)Cys4057 6,7 and apoBCys4326.8,9 Hydrodynamic studies of recombinant Lp(a) particles showed that a single copy of apo(a) attaches to the single copy of apoB on the LDL surface with minimal contact between the two proteins.10 More recent electron microscopy studies, however, have shown apo(a) to be wrapped around the LDL molecule suggesting multiple contacts between the apo(a) and apoB proteins.11 This observation is supported by many studies that have identified multiple apo(a) sequences that interact noncovalently with apoB and vice versa. Some of these interactions are likely to be involved in the assembly of Lp(a) while others could be formed post-assembly to help stabilise the structure.

Lp(a) Assembly

The majority of evidence suggests that Lp(a) assembly occurs extracellularly, either in circulation or at the hepatocyte surface (reviewed in reference 12). There is, however, some evidence for intracellular assembly from kinetic studies in humans.13 Studies over the last decade have indicated that Lp(a) is assembled in a two-step manner involving noncovalent interactions between apo(a) and apoB that precede the formation of the disulphide bond between apo(a)Cys4057 and apoBCys4326.6,14 Experiments showing that lysine analogues disrupt Lp(a) assembly have suggested that lysine binding domains in apo(a) and lysine residues in apoB are involved in the initial non-covalent interaction.15,16 Mutagenesis studies documenting defective Lp(a) assembly after the removal of lysine binding sites in apo(a) KIV types 6–8 have provided further evidence for this.17 A recent study in which single point mutations were introduced into the lysine binding sites in KIV 6–8 has revealed that KIV 7 and 8, but not KIV 6, are required for efficient Lp(a) assembly.18

A number of apoB sequences that noncovalently bind apo(a) have been reported. Becker et al. have identified an apoB lysine residue in the N-terminus, apoBLys680, that mediates the noncovalent binding of an apoB18 fragment to apo(a).19 Subsequent studies have shown that a peptide containing the apoBLys680 residue binds to apo(a) KIV type 7.18 Sequences in the C-terminal region of apoB have also been implicated in the noncovalent interaction with apo(a). Experiments with truncated apoB molecules identified a region between apoB95 (4330 amino acids) and apoB97 (4397 amino acids) that was important for efficient Lp(a) assembly.20 Further characterisation of the apoB4330 to 4397 region identified a 21 amino acid sequence (amino acids 4372–4392) containing four lysine residues (including a highly conserved lysine at position 4372) that posed a potential apo(a) binding site.21 A peptide spanning this sequence was shown to bind apo(a) and completely inhibit Lp(a) formation in vitro.21 Furthermore, mutation of lysine residues in the apoB4372–4392 sequence impairs Lp(a) assembly in transgenic mice expressing a full length apoB mutant.22

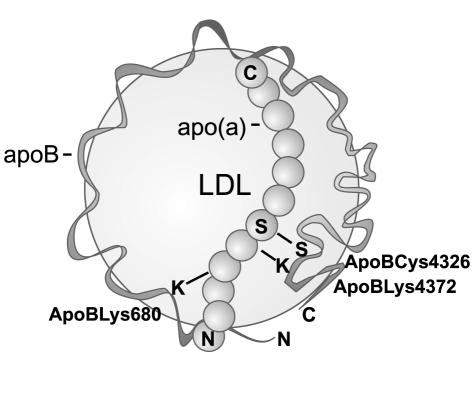

All of the above studies suggest that the assembly of Lp(a) is complex and requires multiple apo(a)/apoB interactions for the efficient association of the two proteins before formation of the disulphide bond. A proposed model for the assembly of Lp(a) based on current data is shown in Figure 1. Future research in this area will aim to identify the exact amino acid interactions between apo(a) and apoB that are crucial for Lp(a) assembly and may provide new targets for the development of Lp(a)-lowering drugs. The crystal structures for some of the apo(a) KIV domains have recently been solved and will surely aid such an endeavour.23,24

Figure 1.

Model of Lp(a) assembly. Lp(a) is formed through a two-step assembly mechanism involving initial non-covalent interactions between lysine residues in apoB (possibly Lys680 and Lys4372) and lysine binding domains in apo(a). These initial interactions precede the formation of a disulphide bond between apo(a)Cys4057 and apoBCys4326. N, N-terminus; C, C-terminus.

Lp(a) Metabolism

Despite years of research, the metabolic fate of Lp(a) has proven elusive. Because of its similarity to LDL, it was originally thought that Lp(a) would be cleared via the LDL receptor (LDLR). Some studies of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) individuals with mutant LDLRs have supported this hypothesis by showing that FH individuals have higher Lp(a) levels than control subjects.25–27 In contrast with these findings, an in vivo kinetic study of FH subjects demonstrated that the LDLR was not required for Lp(a) catabolism.28 Animal studies support a role for the LDLR in Lp(a) uptake since mice overexpressing the LDLR gene have an increased clearance of Lp(a)29 and rabbits deficient in the LDLR gene, conversely show elevated Lp(a) levels.30 One major body of evidence that does not support a role for the LDLR in Lp(a) clearance is large clinical trials that report no effect of the statins on Lp(a) levels.31, 32 Since the statins work by upregulating expression of the LDLR gene, one would have expected these drugs to be effective Lp(a)-lowering agents if the LDLR played a major role in Lp(a) clearance. In vitro evidence for Lp(a) binding to the LDLR is also lacking with cell culture studies showing that Lp(a) has a low affinity for the LDLR.33, 34

The major site of Lp(a) metabolism from animal studies appears to be the liver 35, 36 with some accumulation reported in muscle and spleen. Fragments of apo(a) are found in human urine suggesting that the kidney also plays a role in Lp(a) clearance although it is not a major route for Lp(a) catabolism.37 Cell culture studies have documented that Lp(a) can interact with other members of the LDLR family including the megalin/gp330 and VLDL receptors (reviewed in reference 38); however, the physiological importance of these interactions are unproven. Recently, Kostner et al. have identified an asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) that is highly expressed in the liver which binds and internalises Lp(a).39 A series of in vivo experiments in hedgehogs and ASGPR knockout mice suggest that this receptor may constitute a major pathway for liver uptake of Lp(a).39

Lp(a) as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor

Many large clinical trials have shown elevated levels of Lp(a) to be an independent risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease.40–42 A meta-analysis of 5436 CHD subjects from 27 prospective studies concluded that individuals in the upper third of Lp(a) measurements were 70% more likely to develop CHD than those individuals in the bottom third.43 The commonly cited cut-off value for Lp(a) becoming a risk factor is 300 mg/L. Most large cardiovascular studies have evaluated Lp(a) as a modest risk factor with odds ratios around 2 for those individuals above the cut-off level. There is, however, evidence from some studies that the risk of developing CHD from an elevated Lp(a) level is exacerbated in the presence of other lipid risk factors such as high LDL cholesterol or low HDL cholesterol levels.41,44 This is also the case when elevated levels of Lp(a) are found in combination with thrombogenic risk factors such as Factor V Leiden, protein C deficiency and antithrombin III deficiency.45 From this perspective, it may be prudent to aggressively treat modifiable risk factors in individuals that also have elevated Lp(a) levels.

As well as the clinical association of high levels of Lp(a) with CHD, there are multiple studies documenting the deposition of Lp(a) in human arteries affected by atherosclerosis. Immunohistochemical staining for Lp(a) has been documented in the aorta 46 as well as coronary,47 cerebral 48 and peripheral vessels 49 with the relative amount of Lp(a) deposition being related to the extent of atherosclerosis.48 Studies in rabbits have also demonstrated accumulation of injected human Lp(a) in balloon-injured and atherosclerotic arteries.50,51 The retention of Lp(a) in the arterial wall is likely due to apo(a)’s affinity for extracellular matrix proteins.52 Hughes et al. have shown that Lp(a)’s affinity for the extracellular matrix is mediated via lysine binding sites in apo(a) and that mutating these sites reduces Lp(a) deposition in the vascular wall.53 Lp(a) can be deposited intact or as fragments of apo(a). The generation of apo(a) fragments is most likely from proteolytic cleavage by elastases or metalloproteinases secreted by cells in the arterial wall.54 Once deposited, both intact Lp(a) and apo(a) fragments can elicit a range of biological activities (discussed below) that fuel the development of atherosclerosis.

Lp(a) in Animal Models

The use of animals to study Lp(a) is limited by the unusual species distribution of apo(a) which is found only in humans, old world monkeys and the hedgehog.2 Interestingly, hedgehog apo(a) is different from the primate version with respect to the duplication of plasminogen kringle domains, indicating an independent evolution.55 Both human apo(a) transgenic mice and rabbits have been generated to use as models to study the metabolism and pathogenicity of Lp(a). The first study of apo(a) transgenic mice by Lawn et al. reported significantly larger lesions in the transgenic mice compared to their nontransgenic littermates, when fed an atherogenic diet.56 Interestingly, mouse apoB lacked the covalent linkage to human apo(a), yet was still found associated with apo(a) in the lesioned areas, suggesting a non-covalent association between the two proteins.56 This association of mouse apoB with human apo(a) has been confirmed by other studies.57,58 A recent study of apo(a) transgenic mice, using much older animals than previously studied by Lawn, showed that the majority of these animals developed lesions on a chow diet in contrast to non-transgenic littermates reiterating the finding that apo(a) does promote atherosclerosis in mice.59

A number of investigators have generated bona fide Lp(a) transgenic mice by crossing the apo(a) transgenic mice with human apoB transgenic mice.60,61 These animals have higher LDL levels than apo(a) transgenic mice and contain covalently bound Lp(a) in their plasma; a situation more representative of the human one. Atherosclerosis studies of these animals, however, have provided conflicting results. An initial study by Callow et al. showed an 8-fold increase in lesion size in Lp(a) animals fed a high fat diet compared to nontransgenic littermates, with the presence of Lp(a) proving more atherogenic than expression of the apo(a) or apoB transgenes alone.62 Two subsequent studies of Lp(a) transgenic mice were at variance with this initial finding. Mancini et al. showed no difference in lesion area between Lp(a) and nontransgenic animals fed a high fat diet.57 Sanan et al. reported no effect of apo(a) on atherosclerosis development when Lp(a) transgenic mice were compared to human apoB transgenic mice on a LDLR knockout background.63

In contrast to the transgenic mouse model, expression of apo(a) in transgenic rabbits has consistently proven Lp(a) to be atherogenic. Fan et al. demonstrated that the expression of apo(a) promoted extensive fatty streak lesions in rabbits fed a cholesterol-rich diet.64 Furthermore, lesions developed along the length of the aorta, unlike mice in which the lesions are mainly confined to the proximal aorta. The association of apo(a) with the development of atherosclerosis is even more striking when the apo(a) transgene is expressed in the Watanabe Heritable Hyperlipidemic (WHHL) rabbit.65 These animals spontaneously develop lesions that are similar in composition to the human “vulnerable plaque” containing a necrotic core of foam cells, proliferated smooth muscle cells and a fibrous cap. The higher LDL levels in rabbits compared to mice and the ability of rabbit apoB to form a covalent linkage with human apo(a), may account for the tighter association between apo(a) expression and atherosclerosis in transgenic rabbits compared to transgenic mice.66 Nevertheless, both models have provided useful insight into Lp(a) metabolism and mechanisms that may account for Lp(a)’s pathogenicity.

Pathogenicity of Lp(a)

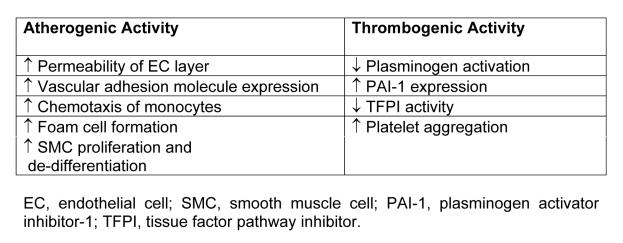

The physiological role of Lp(a) remains unknown, although a number of possible functions have been proposed (reviewed in reference 67). Lp(a) is certainly not essential, since a considerable number of individuals have no detectable Lp(a) with no apparent consequence. Probably the most likely function for Lp(a) is a role in wound healing. This makes biological sense given apo(a)’s affinity for fibrin, its ability to promote cell division and to carry a cholesterol load that could be used for wound repair. Most of the research on Lp(a) has centred around elucidating its role in promoting atherosclerosis. These studies have uncovered an array of biological activities produced by Lp(a) (see Table 1) that could explain its role in the development of CHD.

Table 1.

Lp(a) has an affinity for many components of the subendothelial matrix including proteoglycans,68 fibrinogen and fibronectin.52 Indeed, studies in rabbits have shown that Lp(a) can be retained in the arterial wall to a greater extent than LDL.51 Lp(a) also binds to triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, a property which may contribute to the accumulation of lipid in the arterial wall.69 Lp(a), like LDL, is subject to oxidative modification to become a substrate for uptake by macrophages thereby fuelling the formation of foam cells.70 Also like oxidised LDL, Lp(a) seems to have inflammatory properties promoting the chemotaxis of monocytes 71 and inducing the expression of vascular adhesion molecules.72

Apo(a)’s similarity to plasminogen has initiated much research into the effect of Lp(a) on fibrinolysis with the hypothesis that it could interfere with plasminogen action and promote thrombosis. Indeed, numerous studies have confirmed that Lp(a) does interfere with plasminogen activation by multiple mechanisms. Early cell culture studies showed that both Lp(a) and apo(a) bound to fibrin with high affinity and that Lp(a) could compete with plasminogen for fibrin binding to impair plasminogen activation.73 Interestingly, smaller apo(a) isoforms have a higher affinity for fibrin than larger isoforms suggesting that smaller isoforms may be associated with a greater risk of thrombosis.74 A recent study suggests that as well as binding to fibrin, apo(a) also interacts with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and plasminogen within the fibrinolytic complex to alter the kinetics and slow plasmin generation.75 Studies of cultured endothelial cells have also shown that Lp(a) can upregulate the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which in turn reduces the amount of tPA available for plasminogen activation.76 Other thrombogenic properties reported for Lp(a) include an ability to promote platelet aggregation77 and the ability to inactivate tissue factor pathway inhibitor, a major regulator of the coagulation cascade.78 Both animal and some human studies have provided evidence that Lp(a) is thrombotic in nature (reviewed in reference 79).

Another feature of Lp(a) is its growth-factor-like properties, which is unsurprising considering apo(a) belongs to a growth factor family.80 In vitro studies have shown that Lp(a) stimulates the growth of endothelial and smooth muscle cells.81,82 Lp(a)’s capacity to promote smooth muscle cell proliferation has been a feature in animal studies. Ichikawa et al. documented an increase in smooth muscle cell proliferation in areas of Lp(a) accumulation in transgenic rabbits.83 Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis of the smooth muscle cell layer showed expression of markers relating to proliferation and de-differentiation. Grainger et al. identified the mechanism by which Lp(a) stimulates smooth cell growth, after demonstrating that Lp(a) inhibited the activation of transforming growth factor-β, a negative regulator of smooth muscle cell proliferation.82

A recent study by Pelligrino et al. has identified yet another mechanism for Lp(a)’s involvement in atherogenesis, by showing that the apo(a) component of Lp(a) induces a rearrangement of actin fibres in cultured endothelial cells.84 This leads to a loss of cell to cell contact which may contribute to the initial damage and increased endothelial layer permeability that precedes the development of atherosclerotic lesions.

Lp(a) Measurement

Lp(a) is currently measured by a range of commercially available immunoassays including enzyme-linked-immunoabsorbant (ELISA), immunoturbidometric and immunonephelometric assays that use antibodies specific to the apo(a) moiety of Lp(a). A dilemma exists with most of these methods with respect to the affinity of the antibodies to different apo(a) size isoforms. A considerable number of methods are based on antibodies that have epitopes within the repetitive KIV type 2 kringle. This results in a varying immunoreactivity of the antibody to the samples being measured depending on the number of KIV type 2 repeats. Furthermore, because the calibrator used to standardise the assay will not be representative of the majority of apo(a) isoforms being measured, those samples containing smaller isoforms than the calibrator will be underestimated and conversely those having larger isoforms will be overestimated. This impact of apo(a) size on Lp(a) measurement has been well documented by Marcovina et al. who developed two ELISA assays for Lp(a), one using an antibody, MAb a5, specific to the repetitive KIV type 2 kringle and one using an antibody, MAb a40, specific to the unique KIV type 9 kringle.85 Both assays were calibrated with an apo(a) standard containing 21 KIV repeats and then used to measure Lp(a) in a large number of individuals. As expected, identical values were obtained by the two ELISA methods when samples containing apo(a) isoforms with 21 KIV repeats were measured. However, samples with apo(a) isoforms >21 KIV repeats were overestimated, and samples with apo(a) isoforms <21 KIV repeats were underestimated using the MAb a5 assay compared to the MAb a40 assay. The MAb a40 assay has been validated in studies with a large number of individuals.86 It has also been used to demonstrate that the apo(a) size dependent bias exists with the majority of commercially available assays.87

With such a variety of assays being used and no common calibrator, standardisation of Lp(a) measurement between laboratories is difficult. Storage of samples for Lp(a) measurement can also be an issue, with prolonged storage of samples at sub-optimal temperatures leading to the physical breakdown of the Lp(a) particle and changes in its immunoreactivity.88While it is not possible to eliminate all of these differences, a recent report from a NHLBI workshop on Lp(a) provides recommendations on how to reduce Lp(a) measurement inaccuracies.89

Lp(a) Levels: Genetic Influences

Plasma concentrations of Lp(a) are highly heritable, hugely variable and largely unaltered by environmental factors. Differences in Lp(a) levels exist between populations, suggesting ethnic differences in the control of Lp(a) levels. For example, African populations have higher levels compared to Caucasian populations.90 Within populations, Lp(a) levels can vary over 1000-fold between individuals.4 The highly heterogeneous apo(a) gene accounts for much of this variation. The apo(a) size polymorphism clearly has a large influence on Lp(a) levels, as first discovered by Utermann who showed an inverse relationship between the number of KIV repeats and plasma Lp(a) levels.5 Cell culture studies have since shown that this relationship is due to a lowered efficiency of secretion of the larger isoforms.91

Multiple studies have confirmed the inverse relationship between apo(a) size and Lp(a) level suggesting that the apo(a) size polymorphism accounts for the majority of variation in plasma Lp(a) levels depending on the population studied.4 However, even subjects with the same-sized apo(a) alleles, can have Lp(a) concentrations that vary by up to 200 fold.92 Other sequence variations in the apo(a) gene have been reported to influence Lp(a) levels. These include a pentanucleotide repeat polymorphism in the promoter,93 a C/T polymorphism in the 5′ untranslated region93 and a G to A substitution in the +1 donor site of the KIV type 8 intron, which generates a null allele.94 While these sequence variations may account for some of the remaining differences in Lp(a) levels, it is highly likely that other genes involved in the assembly and metabolism of Lp(a) also contribute to the control of Lp(a) levels. Indeed, a recent linkage study identified a significant linkage between plasma Lp(a) levels and a region on chromosome 19 (LOD score 3.8) in a non-Hispanic American population.95 Interestingly, the LDLR gene lies in the approximate region identified. Another linkage study of Western European families identified a region on chromosome 1 as having a significant influence on Lp(a) levels.96 Future studies will undoubtedly identify other genes that control Lp(a) levels, although their influence is likely to be minor compared to that exerted by the apo(a) gene.

Lp(a) Levels: Other influences

Lp(a) levels can be increased in certain disease conditions such as renal disease.97 There is also evidence that Lp(a) behaves as an acute phase reactant, with some studies showing significant increases in Lp(a) levels following tissue injury.98 A number of studies have reported associations between Lp(a) and inflammatory cytokines including tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), interleukin 6 (IL6) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1).99,100 Interestingly, the apo(a) gene contains multiple IL6 response elements101 and cell culture studies have shown that apo(a) gene expression is up-regulated by IL6, leading to an accumulation of Lp(a) particles.102 Yano et al. using immunohistochemical techniques, showed accumulation of Lp(a) in inflamed tissues, providing support for the notion that Lp(a) is involved in the wound healing process.103 An increase in Lp(a) levels with inflammation, combined with Lp(a)’s affinity for extracellular matrix proteins, may well underlie the accumulation of Lp(a) in the artery in the early phases of atherosclerosis.

Lp(a) levels are generally very resistant to changes in diet, although there is evidence that dietary fat lowers Lp(a) levels. Hornstra et al. documented a lowering of plasma Lp(a) levels in individuals placed on diets rich in saturated fat.104 In keeping with this, Ginsberg et al. reported an increase in Lp(a) levels in individuals after they reduced their saturated fat intake.105 Monosaturated fats also seem to reduce Lp(a) levels, as shown by a recent study that reported a significant decrease in Lp(a) levels in individuals whose diets were supplemented with almonds.106 A high intake of polyunsaturated fats may also lower Lp(a). Marcovina et al. documented significantly lower levels of Lp(a) in a population of Bantu fisherman compared to a nearby Bantu population existing on a vegetarian-based diet.107 This finding was supported by a significant inverse relationship between plasma omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and Lp(a) levels. Calorie restricted diets may favourably influence Lp(a) levels. One study of obese women with high Lp(a) levels did report a significant decrease in levels after 6 weeks on a calorie restricted diet.108 Finally, the lipid-lowering effect of alcohol also seems to apply to Lp(a).109,110

Lp(a) Lowering Interventions

Lp(a) levels are generally unresponsive to traditional lipid-lowering drugs, such as the statins or fibrates. One exception is niacin, which has routinely been shown to effectively lower Lp(a) levels, when given in high doses (2 to 3 g/day).111 The action of niacin appears to be through reducing Lp(a) production rates. Unfortunately, high doses of niacin can be associated with headaches, flushing and liver toxicity; side effects that can lead to non-compliance. Two less traditional lipid-modifying therapies that effectively lower Lp(a) levels are LDL apheresis and hormone replacement therapy. LDL apheresis has been reported to lower Lp(a) levels by greater than 50%.112 However, this procedure is very costly, time consuming, and usually reserved for people with extreme forms of hypercholesterolaemia, such as FH homozygotes. Trials of post-menopausal women receiving various forms of estrogen replacement therapy have shown quite large decreases in Lp(a) levels particularly in those individuals with high baseline levels.113 The action of estrogen is likely through a reduction in apo(a) secretion from the liver, since the apo(a) gene contains an estrogen receptor response element and studies in HepG2 cells have shown that estrogen reduces apo(a) expression.114 While estrogen therapy may be an effective Lp(a)-lowering agent, its controversial effect on cardiovascular risk and safety with respect to increasing the risk of certain cancers, will no doubt prevent its use as a routine means to lower Lp(a).

Other agents reported to lower Lp(a) levels include 2 g per day L-carnitine,115 a combination of L-lysine and ascorbate (3g/day of each)116 and the cholestin extract, Xuezhikang (1.2 g/day).117 A recent trial in 37 Japanese patients with high Lp(a) levels (>300 mg/L) has shown that low doses of aspirin (81 mg/day) decrease Lp(a) levels by approximately 20%.118 The aspirin affect is intriguing given Lp(a)’s possible role as an acute phase response protein. Interestingly, aspirin has been shown to reduce apo(a) transcriptional activity in human hepatocytes and interferes with the IL6 enhancement of apo(a) transcription.119 It will be of interest to see if the Lp(a)-lowering activity of aspirin can be repeated in larger scale clinical trials as this may be a cheap and effective means of lowering Lp(a) while reaping the anti-thrombogenic benefits of aspirin therapy. Also worthy of mention as possible Lp(a)-lowering therapies, although still in the experimental stage, are the use of apo(a) anti-sense RNA to reduce apo(a) expression120 and the use of synthetic peptides to inhibit Lp(a) assembly.21

Conclusions

Four decades of research on Lp(a) have seen it emerge as a clinically important molecule. Evidence has been gained for Lp(a)'s involvement in the development of CHD to a point where routine measurement of Lp(a) in patients at risk must be recommended. Much information has also been gained regarding the genetic control, metabolism and biological activity of Lp(a); however, some questions remain in relation to its assembly, catabolism and interactions with other risk factors. One major challenge that still remains is the development of a therapeutic agent to specifically lower Lp(a) levels. The development of a safe and effective means of lowering Lp(a) will provide the opportunity to conduct intervention trials to further decipher Lp(a)’s contribution to the development of CHD.

References

- 1.Berg K. A New Serum Type System in Man-the Lp System. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1963;59:369–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1963.tb01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Utermann G. The mysteries of lipoprotein(a) Science. 1989;246:904–10. doi: 10.1126/science.2530631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean JW, Tomlinson JE, Kuang WJ, et al. cDNA sequence of human apolipoprotein(a) is homologous to plasminogen. Nature. 1987;330:132–7. doi: 10.1038/330132a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaw A, Hobbs HH. Molecular genetics of lipoprotein (a): new pieces to the puzzle. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1994;5:149–55. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199404000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Utermann G, Menzel HJ, Kraft HG, Duba HC, Kemmler HG, Seitz C. Lp(a) glycoprotein phenotypes. Inheritance and relation to Lp(a)-lipoprotein concentrations in plasma. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:458–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI113093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner C, Kraft HG, Utermann G, Muller HJ. Cys4057 of apolipoprotein(a) is essential for lipoprotein(a) assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11643–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koschinsky ML, Cote GP, Gabel B, van der Hoek YY. Identification of the cysteine residue in apolipoprotein(a) that mediates extracellular coupling with apolipoprotein B-100. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19819–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormick SPA, Ng JK, Taylor S, Flynn LM, Hammer RE, Young SG. Mutagenesis of the human apolipoprotein B gene in a yeast artificial chromosome reveals the site of attachment for apolipoprotein(a) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10147–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callow MJ, Rubin EM. Site-specific mutagenesis demonstrates that cysteine 4326 of apolipoprotein B is required for covalent linkage with apolipoprotein (a) in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23914–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips ML, Lembertas AV, Schumaker VN, Lawn RM, Shire SJ, Zioncheck TF. Physical properties of recombinant apolipoprotein(a) and its association with LDL to form an LP(a)-like complex. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3722–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00065a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisel JW, Nagaswami C, Woodhead JL, et al. The structure of lipoprotein(a) and ligand-induced conformational changes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10424–35. doi: 10.1021/bi010556e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dieplinger H, Utermann G. The seventh myth of lipoprotein(a): where and how is it assembled? Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:275–83. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su W, Campos H, Judge H, Walsh BW, Sacks FM. Metabolism of Apo(a) and ApoB100 of lipoprotein(a) in women: effect of postmenopausal estrogen replacement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3267–76. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trieu VN, McConathy WJ. A two-step model for lipoprotein(a) formation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15471–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiesa G, Hobbs HH, Koschinsky ML, Lawn RM, Maika SD, Hammer RE. Reconstitution of lipoprotein(a) by infusion of human low density lipoprotein into transgenic mice expressing human apolipoprotein(a) J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank S, Durovic S, Kostner K, Kostner GM. Inhibitors for the in vitro assembly of Lp(a) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1774–80. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.10.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabel BR, Koschinsky ML. Sequences within apolipoprotein(a) kringle IV types 6–8 bind directly to low-density lipoprotein and mediate noncovalent association of apolipoprotein(a) with apolipoprotein B-100. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7892–8. doi: 10.1021/bi973186w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker L, Cook PM, Wright TG, Koschinsky ML. Quantitative evaluation of the contribution of weak lysine-binding sites present within apolipoprotein(a) Kringle IV types 6–8 to Lp(a) assembly. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309414200. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker L, McLeod RS, Marcovina SM, Yao Z, Koschinsky ML. Identification of a critical lysine residue in apolipoprotein B-100 that mediates noncovalent interaction with apolipoprotein(a) J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36155–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCormick SPA, Ng JK, Cham CM, et al. Transgenic mice expressing human ApoB95 and ApoB97. Evidence that sequences within the carboxyl-terminal portion of human apoB100 are important for the assembly of lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23616–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharp RJ, Perugini MA, Marcovina SM, McCormick SPA. A synthetic peptide that inhibits lipoprotein(a) assembly. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:502–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000055741.13940.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu CY, Broadhurst R, Marcovina SM, McCormick SPA. Mutation of lysine residues in apolipoprotein B-100 causes defective lipoprotein[a] formation. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:63–70. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300071-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye Q, Rahman MN, Koschinsky ML, Jia Z. High-resolution crystal structure of apolipoprotein(a) kringle IV type 7: insights into ligand binding. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1124–9. doi: 10.1110/ps.01701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maderegger B, Bermel W, Hrzenjak A, Kostner GM, Sterk H. Solution structure of human apolipoprotein(a) kringle IV type 6. Biochemistry. 2002;41:660–8. doi: 10.1021/bi011430k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Utermann G, Hoppichler F, Dieplinger H, Seed M, Thompson G, Boerwinkle E. Defects in the low density lipoprotein receptor gene affect lipoprotein (a) levels: multiplicative interaction of two gene loci associated with premature atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4171–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingenhel A, Kraft HG, Kotze M, et al. Concentrations of the atherogenic Lp(a) are elevated in FH. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6:50–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraft HG, Lingenhel A, Raal FJ, Hohenegger M, Utermann G. Lipoprotein(a) in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:522–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.2.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rader DJ, Mann WA, Cain W, et al. The low density lipoprotein receptor is not required for normal catabolism of Lp(a) in humans. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1403–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI117794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmann SL, Eaton DL, Brown MS, McConathy WJ, Goldstein JL, Hammer RE. Overexpression of human low density lipoprotein receptors leads to accelerated catabolism of Lp(a) lipoprotein in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1542–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI114602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan J, Challah M, Shimoyamada H, Shiomi M, Marcovina S, Watanabe T. Defects of the LDL receptor in WHHL transgenic rabbits lead to a marked accumulation of plasma lipoprotein[a] J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1004–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kostner GM, Gavish D, Leopold B, Bolzano K, Weintraub MS, Breslow JL. HMG CoA reductase inhibitors lower LDL cholesterol without reducing Lp(a) levels. Circulation. 1989;80:1313–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.5.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cobbaert C, Jukema JW, Zwinderman AH, Withagen AJ, Lindemans J, Bruschke AV. Modulation of lipoprotein(a) atherogenicity by high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in middle-aged men with symptomatic coronary artery disease and normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol. Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS) Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1491–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maartmann-Moe K, Berg K. Lp(a) lipoprotein enters cultured fibroblasts independently of the plasma membrane low density lipoprotein receptor. Clin Genet. 1981;20:352–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1981.tb01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snyder ML, Polacek D, Scanu AM, Fless GM. Comparative binding and degradation of lipoprotein(a) and low density lipoprotein by human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:339–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu R, Saku K, Kostner GM, et al. In vivo kinetics of lipoprotein(a) in homozygous Watanabe heritable hyperlipidaemic rabbits. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993;23:561–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1993.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank S, Hrzenjak A, Kostner K, Sattler W, Kostner GM. Effect of tranexamic acid and delta-aminovaleric acid on lipoprotein(a) metabolism in transgenic mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1438:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kostner KM, Maurer G, Huber K, et al. Urinary excretion of apo(a) fragments. Role in apo(a) catabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:905–11. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dieplinger H. Lipoprotein(a): the really bad cholesterol? Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27:439–47. doi: 10.1042/bst0270439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hrzenjak A, Frank S, Wo X, Zhou Y, Van Berkel T, Kostner GM. Galactose-specific asialoglycoprotein receptor is involved in lipoprotein (a) catabolism. Biochem J. 2003;376:765–71. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berg K, Dahlen G, Christophersen B, Cook T, Kjekshus J, Pedersen T. Lp(a) lipoprotein level predicts survival and major coronary events in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Clin Genet. 1997;52:254–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb04342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luc G, Bard JM, Arveiler D, et al. Lipoprotein (a) as a predictor of coronary heart disease: the PRIME Study. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163:377–84. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seman LJ, DeLuca C, Jenner JL, et al. Lipoprotein(a)-cholesterol and coronary heart disease in the Framingham Heart Study. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1039–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Danesh J, Collins R, Peto R. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary heart disease. Meta-analysis of prospective studies. Circulation. 2000;102:1082–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Eckardstein A, Schulte H, Cullen P, Assmann G. Lipoprotein(a) further increases the risk of coronary events in men with high global cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:434–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowak-Gottl U, Junker R, Hartmeier M, et al. Increased lipoprotein(a) is an important risk factor for venous thromboembolism in childhood. Circulation. 1999;100:743–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.7.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jurgens G, Chen Q, Esterbauer H, Mair S, Ledinski G, Dinges HP. Immunostaining of human autopsy aortas with antibodies to modified apolipoprotein B and apoprotein(a) Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1689–99. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.11.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rath M, Niendorf A, Reblin T, Dietel M, Krebber HJ, Beisiegel U. Detection and quantification of lipoprotein(a) in the arterial wall of 107 coronary bypass patients. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:579–92. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamieson DG, Usher DC, Rader DJ, Lavi E. Apolipoprotein(a) deposition in atherosclerotic plaques of cerebral vessels. A potential role for endothelial cells in lesion formation. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1567–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cambillau M, Simon A, Amar J, et al. Serum Lp(a) as a discriminant marker of early atherosclerotic plaque at three extracoronary sites in hypercholesterolemic men. The PCVMETRA Group. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12:1346–52. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.11.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen LB, Stender S, Kjeldsen K, Nordestgaard BG. Specific accumulation of lipoprotein(a) in balloon-injured rabbit aorta in vivo. Circ Res. 1996;78:615–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nielsen LB, Stender S, Jauhiainen M, Nordestgaard BG. Preferential influx and decreased fractional loss of lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic compared with nonlesioned rabbit aorta. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:563–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI118824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Hoek YY, Sangrar W, Cote GP, Kastelein JJ, Koschinsky ML. Binding of recombinant apolipoprotein(a) to extracellular matrix proteins. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:1792–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.11.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes SD, Lou XJ, Ighani S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) vascular accumulation in mice. In vivo analysis of the role of lysine binding sites using recombinant adenovirus. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1493–500. doi: 10.1172/JCI119671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scanu AM. Atherothrombogenicity of lipoprotein(a): the debate. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:26Q–33Q. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00733-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lawn RM, Boonmark NW, Schwartz K, et al. The recurring evolution of lipoprotein(a). Insights from cloning of hedgehog apolipoprotein(a) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24004–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lawn RM, Wade DP, Hammer RE, Chiesa G, Verstuyft JG, Rubin EM. Atherogenesis in transgenic mice expressing human apolipoprotein(a) Nature. 1992;360:670–2. doi: 10.1038/360670a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mancini FP, Newland DL, Mooser V, et al. Relative contributions of apolipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein-B to the development of fatty lesions in the proximal aorta of mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1911–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.11.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheesman EJ, Sharp RJ, Zlot CH, et al. An analysis of the interaction between mouse apolipoprotein B100 and apolipoprotein(a) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28195–200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berg K, Svindland A, Smith AJ, et al. Spontaneous atherosclerosis in the proximal aorta of LPA transgenic mice on a normal diet. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163:99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Linton MF, Farese RV, Chiesa G, et al. Transgenic mice expressing high plasma concentrations of human apolipoprotein B100 and lipoprotein(a) J Clin Invest. 1993;92:3029–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI116927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Callow MJ, Stoltzfus LJ, Lawn RM, Rubin EM. Expression of human apolipoprotein B and assembly of lipoprotein(a) in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2130–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Callow MJ, Verstuyft J, Tangirala R, Palinski W, Rubin EM. Atherogenesis in transgenic mice with human apolipoprotein B and lipoprotein (a) J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1639–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI118203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanan DA, Newland DL, Tao R, et al. Low density lipoprotein receptor-negative mice expressing human apolipoprotein B-100 develop complex atherosclerotic lesions on a chow diet: no accentuation by apolipoprotein(a) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4544–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fan J, Shimoyamada H, Sun H, Marcovina S, Honda K, Watanabe T. Transgenic rabbits expressing human apolipoprotein(a) develop more extensive atherosclerotic lesions in response to a cholesterol-rich diet. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:88–94. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fan J, Sun H, Unoki H, Shiomi M, Watanabe T. Enhanced atherosclerosis in Lp(a) WHHL transgenic rabbits. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;947:362–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fan J, Araki M, Wu L, et al. Assembly of lipoprotein (a) in transgenic rabbits expressing human apolipoprotein (a) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255:639–44. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lippi G, Guidi G. Lipoprotein(a): from ancestral benefit to modern pathogen? QJM. 2000;93:75–84. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lundstam U, Hurt-Camejo E, Olsson G, Sartipy P, Camejo G, Wiklund O. Proteoglycans contribution to association of Lp(a) and LDL with smooth muscle cell extracellular matrix. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1162–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.5.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gaubatz JW, Hoogeveen RC, Hoffman AS, et al. Isolation, quantitation, and characterization of a stable complex formed by Lp[a] binding to triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:2058–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haberland ME, Fless GM, Scanu AM, Fogelman AM. Malondialdehyde modification of lipoprotein(a) produces avid uptake by human monocyte-macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4143–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poon M, Zhang X, Dunsky KG, Taubman MB, Harpel PC. Apolipoprotein(a) induces monocyte chemotactic activity in human vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 1997;96:2514–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Allen S, Khan S, Tam S, Koschinsky M, Taylor P, Yacoub M. Expression of adhesion molecules by lp(a): a potential novel mechanism for its atherogenicity. FASEB J. 1998;12:1765–76. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.15.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rouy D, Grailhe P, Nigon F, Chapman J, Angles-Cano E. Lipoprotein(a) impairs generation of plasmin by fibrin-bound tissue-type plasminogen activator. In vitro studies in a plasma milieu. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:629–38. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.3.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kang C, Dominguez M, Loyau S, Miyata T, Durlach V, Angles-Cano E. Lp(a) particles mold fibrin-binding properties of apo(a) in size-dependent manner: a study with different-length recombinant apo(a), native Lp(a), and monoclonal antibody. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1232–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000021144.87870.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hancock MA, Boffa MB, Marcovina SM, Nesheim ME, Koschinsky ML. Inhibition of plasminogen activation by lipoprotein(a): critical domains in apolipoprotein(a) and mechanism of inhibition on fibrin and degraded fibrin surfaces. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23260–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levin EG, Miles LA, Fless GM, et al. Lipoproteins inhibit the secretion of tissue plasminogen activator from human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:438–42. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.3.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rand ML, Sangrar W, Hancock MA, et al. Apolipoprotein(a) enhances platelet responses to the thrombin receptor-activating peptide SFLLRN. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1393–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.9.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Caplice NM, Panetta C, Peterson TE, et al. Lipoprotein (a) binds and inactivates tissue factor pathway inhibitor: a novel link between lipoproteins and thrombosis. Blood. 2001;98:2980–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marcovina SM, Koschinsky ML. Evaluation of lipoprotein(a) as a prothrombotic factor: progress from bench to bedside. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14:361–6. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Donate LE, Gherardi E, Srinivasan N, Sowdhamini R, Aparicio S, Blundell TL. Molecular evolution and domain structure of plasminogen-related growth factors (HGF/SF and HGF1/MSP) Protein Sci. 1994;3:2378–94. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takahashi A, Taniguchi T, Fujioka Y, Ishikawa Y, Yokoyama M. Effects of lipoprotein(a) and low density lipoprotein on growth of mitogen-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 1996;120:93–9. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grainger DJ, Kirschenlohr HL, Metcalfe JC, Weissberg PL, Wade DP, Lawn RM. Proliferation of human smooth muscle cells promoted by lipoprotein(a) Science. 1993;260:1655–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8503012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ichikawa T, Unoki H, Sun H, et al. Lipoprotein(a) promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation and dedifferentiation in atherosclerotic lesions of human apo(a) transgenic rabbits. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:227–36. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64366-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pellegrino M, Furmaniak-Kazmierczak E, LeBlanc JC, et al. The apolipoprotein(a) component of lipoprotein(a) stimulates actin stress fiber formation and loss of cell-cell contact in cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309705200. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marcovina SM, Albers JJ, Gabel B, Koschinsky ML, Gaur VP. Effect of the number of apolipoprotein(a) kringle 4 domains on immunochemical measurements of lipoprotein(a) Clin Chem. 1995;41:246–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marcovina SM, Albers JJ, Wijsman E, Zhang Z, Chapman NH, Kennedy H. Differences in Lp[a] concentrations and apo[a] polymorphs between black and white Americans. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:2569–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marcovina SM, Albers JJ, Scanu AM, et al. Use of a reference material proposed by the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine to evaluate analytical methods for the determination of plasma lipoprotein(a) Clin Chem. 2000;46:1956–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kronenberg F, Trenkwalder E, Dieplinger H, Utermann G. Lipoprotein(a) in stored plasma samples and the ravages of time. Why epidemiological studies might fail. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:1568–72. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.12.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marcovina SM, Koschinsky ML, Albers JJ, Skarlatos S. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop on Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Disease: recent advances and future directions. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1785–96. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.023689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sandholzer C, Hallman DM, Saha N, et al. Effects of the apolipoprotein(a) size polymorphism on the lipoprotein(a) concentration in 7 ethnic groups. Hum Genet. 1991;86:607–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00201550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.White AL, Rainwater DL, Hixson JE, Estlack LE, Lanford RE. Intracellular processing of apo(a) in primary baboon hepatocytes. Chem Phys Lipids. 1994;67–68:123–33. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Perombelon YF, Soutar AK, Knight BL. Variation in lipoprotein(a) concentration associated with different apolipoprotein(a) alleles. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1481–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI117126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Trommsdorff M, Kochl S, Lingenhel A, et al. A pentanucleotide repeat polymorphism in the 5' control region of the apolipoprotein(a) gene is associated with lipoprotein(a) plasma concentrations in Caucasians. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:150–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI118015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ogorelkova M, Gruber A, Utermann G. Molecular basis of congenital lp(a) deficiency: a frequent apo(a) 'null' mutation in caucasians. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2087–96. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barkley RA, Brown AC, Hanis CL, Kardia SL, Turner ST, Boerwinkle E. Lack of genetic linkage evidence for a trans-acting factor having a large effect on plasma lipoprotein[a] levels in African Americans. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1301–5. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300163-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Broeckel U, Hengstenberg C, Mayer B, et al. A comprehensive linkage analysis for myocardial infarction and its related risk factors. Nat Genet. 2002;30:210–4. doi: 10.1038/ng827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kronenberg F, Utermann G, Dieplinger H. Lipoprotein(a) in renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27:1–25. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maeda S, Abe A, Seishima M, Makino K, Noma A, Kawade M. Transient changes of serum lipoprotein(a) as an acute phase protein. Atherosclerosis. 1989;78:145–50. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(89)90218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stenvinkel P, Heimburger O, Tuck CH, Berglund L. Apo(a)-isoform size, nutritional status and inflammatory markers in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1336–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Szalai C, Duba J, Prohaszka Z, et al. Involvement of polymorphisms in the chemokine system in the susceptibility for coronary artery disease (CAD). Coincidence of elevated Lp(a) and MCP-1 -2518 G/G genotype in CAD patients. Atherosclerosis. 2001;158:233–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wade DP, Clarke JG, Lindahl GE, et al. 5' control regions of the apolipoprotein(a) gene and members of the related plasminogen gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1369–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ramharack R, Barkalow D, Spahr MA. Dominant negative effect of TGF-beta1 and TNF-alpha on basal and IL-6-induced lipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein(a) mRNA expression in primary monkey hepatocyte cultures. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:984–90. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yano Y, Shimokawa K, Okada Y, Noma A. Immunolocalization of lipoprotein(a) in wounded tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:559–68. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hornstra G, van Houwelingen AC, Kester AD, Sundram K. A palm oil-enriched diet lowers serum lipoprotein(a) in normocholesterolemic volunteers. Atherosclerosis. 1991;90:91–3. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(91)90247-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ginsberg HN, Kris-Etherton P, Dennis B, et al. Effects of reducing dietary saturated fatty acids on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in healthy subjects: the DELTA Study, protocol 1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:441–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al. Dose response of almonds on coronary heart disease risk factors: blood lipids, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, lipoprotein(a), homocysteine, and pulmonary nitric oxide: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. Circulation. 2002;106:1327–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028421.91733.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marcovina SM, Kennedy H, Bittolo Bon G, et al. Fish intake, independent of apo(a) size, accounts for lower plasma lipoprotein(a) levels in Bantu fishermen of Tanzania: The Lugalawa Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1250–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.5.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kiortsis DN, Tzotzas T, Giral P, et al. Changes in lipoprotein(a) levels and hormonal correlations during a weight reduction program. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2001;11:153–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marth E, Cazzolato G, Bittolo Bon G, Avogaro P, Kostner GM. Serum concentrations of Lp(a) and other lipoprotein parameters in heavy alcohol consumers. Ann Nutr Metab. 1982;26:56–62. doi: 10.1159/000176544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Paassilta M, Kervinen K, Rantala AO, et al. Social alcohol consumption and low Lp(a) lipoprotein concentrations in middle aged Finnish men: population based study. BMJ. 1998;316:594–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7131.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Crouse JR., 3rd New developments in the use of niacin for treatment of hyperlipidemia: new considerations in the use of an old drug. Coron Artery Dis. 1996;7:321–6. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Armstrong VW, Schleef J, Thiery J, et al. Effect of HELP-LDL-apheresis on serum concentrations of human lipoprotein(a): kinetic analysis of the post-treatment return to baseline levels. Eur J Clin Invest. 1989;19:235–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1989.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shewmon DA, Stock JL, Rosen CJ, et al. Tamoxifen and estrogen lower circulating lipoprotein(a) concentrations in healthy postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:1586–93. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.10.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Boffelli D, Zajchowski DA, Yang Z, Lawn RM. Estrogen modulation of apolipoprotein(a) expression. Identification of a regulatory element. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15569–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sirtori CR, Calabresi L, Ferrara S, et al. L-carnitine reduces plasma lipoprotein(a) levels in patients with hyper Lp(a) Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2000;10:247–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dalessandri KM. Reduction of lipoprotein(a) in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:772–3. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.5.772-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu L, Zhao SP, Cheng YC, Li YL. Xuezhikang decreases serum lipoprotein(a) and C-reactive protein concentrations in patients with coronary heart disease. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1347–52. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Akaike M, Azuma H, Kagawa A, et al. Effect of aspirin treatment on serum concentrations of lipoprotein(a) in patients with atherosclerotic diseases. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1454–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kagawa A, Azuma H, Akaike M, Kanagawa Y, Matsumoto T. Aspirin reduces apolipoprotein(a) (apo(a)) production in human hepatocytes by suppression of apo(a) gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34111–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Frank S, Gauster M, Strauss J, Hrzenjak A, Kostner GM. Adenovirus-mediated apo(a)-antisense-RNA expression efficiently inhibits apo(a) synthesis in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther. 2001;8:425–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]