Abstract

The cognitive deficits associated with HIV-1 infection are thought to primarily reflect neuropathophysiology within the fronto-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits. Prospective memory (ProM) is a cognitive function that is largely dependent on prefronto-striatal circuits, but has not previously been examined in an HIV-1 sample. A form of episodic memory, ProM involves the complex processes of forming, monitoring, and executing future intentions vis-à-vis ongoing distractions. The current study examined ProM in 42 participants with HIV-1 infection and 29 demographically similar seronegative healthy comparison (HC) subjects. The HIV-1 sample demonstrated deficits in time-and event-based ProM, as well as more frequent 24-hour delay ProM failures and task substitution errors relative to the HC group. In contrast, there were no significant differences in recognition performance, indicating that the HIV-1 group was able to accurately retain and recognize the ProM intention when retrieval demands were minimized. Secondary analyses revealed that ProM performance correlated with validated clinical measures of executive functions, episodic memory (free recall), and verbal working memory, but not with tests of semantic memory, retention, or recognition discrimination. Taken together, these findings indicate that HIV-1 infection is associated with ProM impairment that is primarily driven by a breakdown in the strategic (i.e., executive) aspects of retrieving future intentions, which is consistent with a prefronto-striatal circuit neuropathogenesis.

HIV-1 infiltrates the brain during the initial phases of systemic infection where it promotes neuronal and glial injury (e.g., dendritic simplification) (Petito, 2004). Prevalent throughout the neocortex and white matter tracts, HIV-1-associated neuropathology is perhaps most common within the fronto-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits (e.g., Everall et al., 1999). Neuropsychological impairment is evident in 30 to 50% of persons with HIV-1 disease, with the characteristic pattern of deficits thought to reflect a preferential disruption of prefronto-striatal circuits (Reger, Welsh, Razani, Martin, & Boone, 2002). Deficits in motor coordination, information processing speed, working memory, and executive functions are commonly associated with HIV-1 (e.g., Heaton et al., 1995). In contrast, deficits in cognitive functions mediated by the posterior neocortex (e.g., praxis) are less frequently observed in HIV-1 (e.g., Reger et al., 2002).

Deficient episodic (i.e., retrospective) learning and retrieval are also common in individuals with HIV-1 infection (e.g., Murji et al., 2003). Group studies of HIV-1 disease reveal evidence of limited free recall, diminished use of organizational strategies (e.g., semantic clustering), interference effects, inconsistent recall across learning trials, and high rates of repetition errors (Delis et al., 1995; Murji et al., 2003; Peavy et al., 1994). By way of comparison, retention (i.e., consolidation) and recognition discrimination are less commonly affected in persons with HIV-1 disease (e.g., Delis et al., 1995). Taken together, the memory profile of HIV-1-infection is most consistent with dysfunction in the strategic (i.e., executive) aspects of encoding and retrieval as seen in prototypical “subcortical” disorders, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases (e.g., Massman, Delis, Butters, Levin, & Salmon, 1990; Murji et al., 2003). To date, however, the scope of episodic memory research in HIV-1 disease has been limited to studies of retrospective memory (i.e., memory for past events and experiences).

Prospective Memory

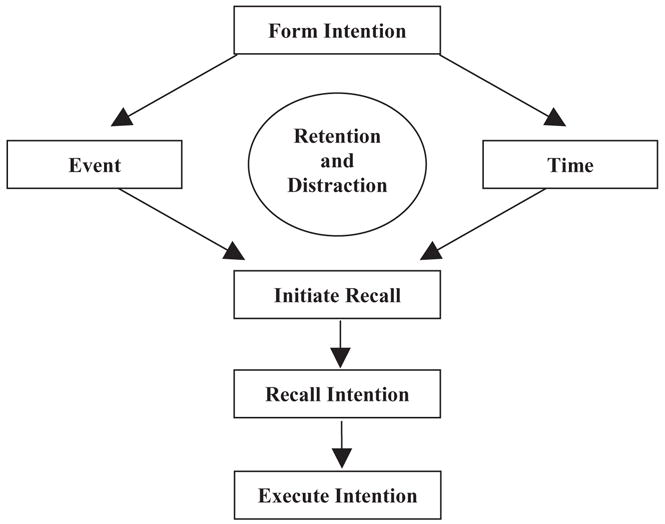

First studied by Loftus (1971), prospective memory (ProM) is a form of episodic memory that encompasses the execution of future intentions, or “remembering to remember.” Specifically, ProM refers to the complex cognitive processes involved in retrieving and performing a previously encoded intention at the appropriate moment in the future (Kvavilashvili & Ellis, 1996). Practical, everyday examples of ProM include remembering to take medications at a particular time or remembering to turn off the stove after preparing a meal. An adapted conceptual model of the cognitive operations involved in ProM is presented in Figure 1 (e.g., Burgess & Shallice, 1997; Dobbs & Reeves, 1996; Ellis, 1996; Knight, 1998). The initial stage of ProM involves the formation of the intention, which requires knowledge about potential factors that could optimize and/or impede performance. Also embedded within this stage is the generation and encoding of the action plan, which requires organizational ability and planning. The second stage involves a retention interval, during which other activities are ongoing so as to preclude simple rehearsal of the encoded intention. Intermittent recollections of the delayed intention may occur, but strategic monitoring is necessary to evaluate whether the designated circumstances are present for performing the intention. The third stage—considered by some theorists to be the defining feature of ProM (e.g., Knight, 1998)—involves self-initiated retrieval, whereby the appropriate cue (e.g., an event) triggers an effortful and controlled search for retrospective recall. ProM requires the independent initiation of a search for the meaning of the cuing stimulus (e.g., “What was I supposed to ask the doctor during my appointment?”). In this way, ProM tasks differ from conventional retrospective recall tasks in which an experimenter explicitly prompts the search for recall. The final stages require the actual recall and execution of the intention, which also necessitate an evaluation of the accuracy and success of the realized intention.

Figure 1.

A Component Process Model of ProM (adapted from Knight, 1998).

An important distinction is often made between event-based (EB) and time-based (TB) ProM tasks (Einstein & McDaniel, 1990). The difference between these two tasks concerns the type of cues that initiate retrieval of the intention. For example, an external stimulus (sometimes embedded in an ongoing activity) provides the cue for action in an EB task (e.g., a mailbox cues the mailing of a letter), whereas in TB tasks, the intended action is performed after a specified time interval (e.g., taking a medication every four hours). It has been hypothesized that TB tasks require slightly different cognitive processes than EB tasks (i.e., a greater emphasis on self-initiated monitoring and retrieval), and empirical evidence suggests that the former are generally more sensitive in older adults (Einstein, McDaniel, Richardson, & Guynn, 1995; cf. Henry, MacLeod, Phillips, & Crawford, 2004) and traumatic brain injury samples (e.g., Cockburn, 1996).

Although ProM requires several different cognitive functions and presumably different neural networks (e.g., temporolimbic circuits), the specific contributions of executive functions and fronto-striatal systems are immediately apparent. Support for the involvement of prefrontal systems in ProM comes from neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies, which reveal the involvement of the fronto-polar and superior rostral aspects of the frontal lobes (e.g., Burgess, Quayle, & Frith, 2001). Moreover, ProM deficits are observed in individuals with frontal lesions (Shallice & Burgess, 1991) and Parkinson’s disease (Katai, Maruyama, Hashimoto, & Ikeda, 2003), as well as in older adults (e.g., Einstein et al., 1995).

The aim of the current study was to provide a hypothesis-driven examination of the nature and extent of ProM impairment in HIV-1 infection. Given the purported sensitivity of ProM tasks to fronto-striatal circuit dysfunction, it was hypothesized that persons with HIV-1 infection would demonstrate impaired ProM relative to demographically comparable seronegative comparison subjects. We further hypothesized that HIV-1-infected individuals would demonstrate particular impairment on TB tasks, but would perform comparably to the comparison group on recognition trials. Finally, we hypothesized that ProM functioning would correlate with performance on standard clinical tests of executive functions, information processing speed, learning, and working memory, but not with measures of retention or semantic memory.

Method

Participants

The study sample included 29 HIV-1 seronegative healthy comparison subjects (HC) and 42 individuals with HIV-1 infection as indicated by enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and a Western Blot confirmatory test. Strict exclusion criteria were enforced so as to minimize the possible confounding effects of comorbid factors known to adversely impact cognition, including psychiatric (e.g., mental retardation, psychotic disorders, diagnosed learning disabilities, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Bipolar Disorders, as well as substance-related disorders within two years of evaluation) and neurologic (e.g., seizure disorders, closed head injuries with loss of consciousness greater than 15 minutes, neoplastic diseases, and central nervous system opportunistic infections) conditions. Participants were also excluded if they exhibited a positive urine toxicology screening for illicit substances on the day of testing (no prospective participants evidenced a positive urine toxicology). Table 1 demonstrates that the HIV-1 and HC groups were generally comparable in age, education, sex, and self-reported symptoms of depression. There was a greater proportion of Caucasian individuals in the HC group as compared to the HIV-1 group (p = 0.05).

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic data and HIV-1 disease and treatment characteristics

| Variable | HC (n = 29) | HIV-1 (n = 42) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.1 (12.2) | 44.4 (8.4) |

| Education (years) | 14.5 (2.4) | 13.9 (2.6) |

| Proportion of men | 72% | 81% |

| Proportion of Caucasiansa | 79% | 59% |

| CD4 lymphocytes, cells/μlb | — | 450 (263, 608) |

| Proportion immunosuppressedc | — | 19% |

| Plasma HIV RNA/μlb | — | 1.9 (0, 4.5) |

| Proportion detectable plasma RNAd | — | 41% |

| CSF HIV RNA/μlb,e | — | 0 (0, 3) |

| Proportion detectable CSF RNAf | — | 36% |

| Proportion with AIDS | — | 79% |

| Proportion on HAART | — | 79% |

| BDI (cognitive-affective scale)b | 1 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 4) |

Note. Data represent means (SD) unless otherwise indicated. HC = healthy comparison subjects. HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy.

p = 0.05.

Median values with interquartile ranges.

CD4 lymphocyte cell count < 200.

Plasma HIV RNA/μl > 2.6.

Subset of HIV + sample (n = 25).

CSF HIV RNA >1.7.

Procedure

After providing informed written consent, all participants were administered the Memory for Intentions Screening Test (MIST; Raskin, 2004) as part of a larger neuropsychological test battery. The MIST is a standardized 30-min measure comprised of eight ProM tasks that correspond to the component process model of ProM described in Figure 1. The MIST contains balanced ProM items that use: 1) a 2-min or 15-min delay; 2) a verbal (e.g., “In 2 min, ask me what time this session ends”) or physical (e.g., “In 15 min, use that paper to write down the number of medications you are currently taking”) response; and 3) a TB (e.g., “In 15 minutes, tell me that it is time to take a break”) or EB (e.g., “When I hand you a postcard, self-address it”) cue. A series of word search puzzles functions as an ongoing distracter task. The MIST also includes a multiple choice recognition trial that is administered following the completion of all eight ProM tasks. Standardized administration requires that recognition prompts be given only for those ProM tasks missed during testing; however, in an effort to more clearly measure the retrieval component of ProM, the current study administered all eight ProM prompts. Finally, a 24-hour probe is administered in which participants are instructed to leave a telephone message for the examiner the following day specifying the number of hours slept the night after the assessment. MIST error types are coded according to the guidelines presented in Table 2. The range of overall summary scores on the MIST is 0 to 48. Preliminary psychometric data on the MIST support its internal (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) and alternate form reliability, as well as its convergent validity with laboratory and everyday measures of ProM (Raskin, 2004).

Table 2.

Operationalization of errors on the MIST

| Error type | Error response |

|---|---|

| No Responsea | |

| Task substitution (action or verbal task) |

|

| Loss of content (action or verbal task) |

|

| Place losing omission |

|

| Loss of time |

|

| Random error |

|

No Response errors are referred to as Prospective Memory errors on the MIST.

The broader neuropsychological battery contained the following tests: 1) Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT-FAS; Benton, Hamsher, & Sivan, 1994; Gladsjo et al., 1999); 2) animal fluency (Gladsjo et al., 1999); 3) Digit Symbol, Letter-Number Sequencing, and Symbol Search subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale –Third edition (WAIS-III; Heaton, Taylor, & Manly, 2002; Psychological Corporation, 1997); 4) Trail Making Test Parts A and B (TMT; Heaton, Grant, & Matthews, 1991; Reitan & Wolfson, 1985); 5) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised (HVLT-R; Brandt & Benedict, 2001); 6) Brief Visuospatial Memory Test – Revised (BVMT-R; Benedict, 1997); 7) Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST 64-item version; Kongs, Thompson, Iverson, & Heaton, 2000); 8) Stroop Color and Word Test (Golden, 1978); 9) Halstead Category Test (Heaton et al., 1991; Reitan & Wolfson, 1985); 10) Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT; Diehr, Heaton, Miller, & Grant, 1998); 11) Grooved Pegboard Test (Heaton et al., 1991; Kløve, 1963); and 12) Reading subtest from the Wide Range Achievement Test – 3 (WRAT-3; Wilkinson, 1993).

An objective summary score of global neuropsychological impairment, the Global Deficit Score (GDS), was derived from the standard test battery (Carey et al., 2004; Heaton et al., 1995). The GDS was generated by converting raw scores to demographically corrected T-scores using published normative data. T-scores for each measure were converted to a zero (no impairment) to 5 (severe impairment) point deficit rating, as follows: >39 T = 0 points, 35–39 T = 1 point; 30–34 T = 2 points; 25–29 T = 3 points; 20–24 T = 4 points; <20 T = 5 points. The GDS was then computed by adding the deficit ratings of the individual test measures and dividing by the total number of measures administered. The recommended GDS cut score of 0.5 (Carey et al., 2004) yielded a 26% rate of global cognitive impairment in the HIV-1 sample.

Statistical Analyses

An a priori power analysis demonstrated that the study sample would provide ample statistical power (>0.80) to detect medium-to-large univariate effect sizes (Erdfelder, Faul, & Buchner, 1996). Because all of the MIST variables were non-normally distributed (Kolmogrov-Smirnov p-values < 0.01), Wilcoxon tests (and the unbiased Cohen’s d measure of effect size) were used to assess between-group differences. Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients were conducted to examine the associations between the MIST summary score and tests selected from the comprehensive neuropsychological battery to provide evidence for the convergent (e.g., executive functions and working memory) and divergent validity (e.g., consolidation and semantic memory) of ProM. Consistent with recent recommendations, the correlational analyses were conducted separately within the HIV-1 and HC samples (Delis, Jacobson, Bondi, Hamilton, & Salmon, 2003). Finally, a receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve and descriptive classification accuracy statistics were generated to examine the abilities of the MIST summary score to detect global neuropsychological impairment in the HIV-1 sample. Using the coordinates of the ROC curve, we selected a cutpoint that provided the best balance between sensitivity and specificity. A critical alpha level of p < 0.05 was used for all analyses, except for the convergent/divergent validity correlations for which we used a more conservative alpha of p < 0.01.

Results

As shown in Table 3, the HIV-1 and HC groups performed comparably on the word search task (p > 0.10). The HIV-1 group scored significantly below the HC group on the MIST total summary score (Cohen’s d = −0.92), TB (d = −0.68) and EB (d = −0.84) tasks, and the 24-hour delay. Error type analyses revealed a large effect for Task Substitution errors (Cohen’s d = 0.84), and medium effects for No Response (Cohen’s d = 0.47) and Loss of Time (Cohen’s d = 0.46) errors. The prevalence of Loss of Content errors, Place Losing Omissions, and Random errors was comparable between groups. No differences were observed on the multiple choice recognition trial (d = −0.30).

Table 3.

ProM performance in the HC and HIV-1 disease samples

| MIST Variable | HC (n = 29) | HIV-1 (n = 42) | p-value | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary score | 45.0 (42.0, 48.0) | 36.0 (29.5, 42.5) | 0.0005 | −0.92 (−1.42, −0.43) |

| Time-based cues | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (5.0, 7.0) | 0.006 | −0.68 (−1.17, −0.19) |

| Event-based cues | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 0.002 | −0.84 (−1.33, −0.35) |

| Total errors | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 0.0003 | 1.02 (0.52, 1.52) |

| No Response | 0.0 (0.0, 0.5) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.09 | 0.47 (−0.01, 0.95) |

| Task Substitution | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 0.001 | 0.84 (0.35, 1.33) |

| Loss of Content | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.66 | 0.17 (−0.31, −0.64) |

| Place Losing | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.41 | 0.17 (−0.30, 0.65) |

| Omission | ||||

| Loss of Time | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.09 | 0.46 (−0.02, 0.94) |

| Random Error | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | — | — |

| Recognition | 8.0 (8.0, 8.0) | 8.0 (8.0, 8.0) | 0.34 | −0.30 (−0.77, 0.18) |

| Word search | 18.0 (16.5, 27.0) | 18.0 (15.0, 31.5) | 0.78 | 0.05 (−0.42, 0.53) |

| 24hr delay (% complete) | 38% | 12% | 0.01 | — |

| Retrieval Index | 1.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 0.02 | 0.69 (0.19, 1.16) |

Note. Data are presented as median values with the interquartile range in parentheses or as valid population percentages (24hr delay only). CI = confidence interval. HC = healthy comparison subjects. MIST = Memory for Intentions Screening Test. ProM = prospective memory.

Retrieval Index = recognition hits-free recall such that higher scores indicate worse performance.

Table 4 displays measures of association between the MIST summary score and the neuropsychological tests selected from the comprehensive battery to examine the convergent and divergent validity of ProM. Within the HC sample, significant correlations were observed between the MIST and the Stroop interference trial and BVMT-R Total Trials 1–3, as well as trend-level associations with PASAT and Halstead Category Test (ps < 0.05). Generally stronger findings emerged in the HIV-1 sample, where significant correlations were observed between the MIST and tests of executive functions (e.g., WCST-64 categories completed), verbal working memory (e.g., PASAT), as well as both verbal and visual learning (e.g., HVLT-R semantic clustering). No significant correlations were found between the MIST and measures of lexical-semantic memory (e.g., WRAT-3 reading and animal fluency) in either study group. Similarly, no significant associations were observed between the MIST and memory savings scores (i.e., retention) or recognition discrimination.

Table 4.

Correspondence between MIST summary score and traditional neuropsychological tests

| Domain and measure | HC (n = 29) | HIV-1 (n = 42) |

|---|---|---|

| Learning | ||

| HVLT-R Trials 1–3 | 0.03 | 0.46*** |

| HVLT-R Semantic Clustering | −0.06 | 0.41** |

| BVMT-R Trials 1–3 | 0.46** | 0.45*** |

| Retrospective Memory | ||

| HVLT-R Retention | 0.20 | 0.31 |

| BVMT-R Retention | −0.05 | 0.12 |

| HVLT-R Recognition | −0.05 | 0.09 |

| BVMT-R Recognition | 0.09 | −0.30 |

| Executive Functions | ||

| TMT B | −0.32 | −0.44*** |

| WCST-64 Categories | 0.30 | 0.39** |

| Halstead Category Test (errors) | −0.38* | −0.29 |

| Stroop Interference | 0.58**** | −0.004 |

| Working Memory | ||

| WAIS-III Letter Number Sequencing | 0.36 | 0.32* |

| PASAT | 0.43* | 0.58**** |

| Processing Speed | ||

| TMT A | −0.34 | −0.36* |

| WAIS-III PSI | 0.21 | 0.35* |

| Lexical-Semantic Memory | ||

| WRAT-3 Reading | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| Category Fluency (animals) | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Letter Fluency (FAS) | −0.09 | 0.15 |

Note. Data are presented as Spearman rho correlation coefficients. BVMT-R = Brief Visuospatial Memory Test – Revised; HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised; MIST = Memory for Intentions Screening Test; TMT = Trailmaking Test; PASAT = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; WAIS-III PSI = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third edition Processing Speed Index; WRAT-3 = Wide Range Achievement Test – Revision 3.

p ≤ 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

p < 0.005.

p < 0.001.

ROC analyses displayed in Table 5 show that the MIST summary score performed significantly better than chance in correctly classifying HIV-1-infected participants as globally neuropsychologically impaired or unimpaired (p = 0.001). In fact, HIV-1 subjects with MIST summary scores below 35 were almost 8 times more likely to be globally neuropsychologically impaired than HIV + persons scoring above cutoff (odds ratio = 7.7, p = 0.01). This MIST cutoff demonstrated a reasonable sensitivity (0.73) and specificity (0.74), with an overall hit rate of 74%.

Table 5.

Classification accuracy of the MIST summary score in predicting global neuropsychological impairmenta

| Variable | ROC (SE) | Hit Rate | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIST Summary (<35) | 0.83** (0.64) | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.89 | 7.7* |

Note. Classification accuracy statistics were calculated between the neuropsychologically impaired (n = 11) and unimpaired (n = 31) participants in the HIV+ group.

Neuropsychological impairment was defined as a Global Deficit Score ≥ 0.5. ROC = Total area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; SE = standard error for the area under the ROC curve; PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value;

p = 0.01.

p = 0.001.

Discussion

Consistent with our original hypotheses, results from the current study provide evidence of ProM impairment in persons with HIV-1-infection; that is, individuals with HIV-1 disease experience difficulty with the complex cognitive processes involved in performing future intentions. Deficits in ProM are commensurate with the predominant fronto-striatal neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 disease, as well as with prior research demonstrating deficient strategic encoding and retrieval in episodic retrospective memory. It is unlikely that findings from the current study are confounded by demographic factors or depressive symptoms, as the HIV + and HC groups were comparable for age, years of education, and sex. Although there was a slightly larger proportion of Caucasian participants in the HC group, post-hoc analyses revealed no main effect for ethnicity on the MIST summary score, nor any interaction between ethnicity and HIV serostatus (ps > 0.10). Furthermore, the HIV-1 and HC groups reported comparable levels of depressive symptoms, and depression (as measured by the BDI) did not correlate with the MIST summary score (p > 0.10). It is also unlikely that the discrepant ProM performance in the HIV-1 and HC groups was the result of differential effort toward the task since the groups performed similarly on the word search distracter test.

Instead, the profile of ProM impairment in HIV-1 is interpreted to reflect deficient retrieval of future intentions. In support of this interpretation, the HIV-1 group performed comparably to the HC sample on the recognition task, which indicates that reducing the self-initiated retrieval demands of the task allowed the HIV-1 group to more effectively identify the correct intention and cue. This pattern of ProM retrieval difficulties is consistent with the episodic learning and retrieval profile that has been consistently identified in HIV-1 disease on traditional retrospective recall tasks (e.g., Murji et al., 2003). Specifically, persons with HIV-1 often exhibit dysfunction in the strategic or “executive” aspects of both retrospective and prospective episodic memory tasks, but not in consolidation. Such executive aspects include difficulties organizing and planning an effective recall strategy, as well as problems encoding (e.g., deficient semantic clustering), which may adversely impact the efficiency and accuracy of retrieval. Likewise, a disorganized or inefficient plan for searching and retrieving the correct information from episodic memory stores would also be manifested in ProM task substitutions (e.g., repetition and intrusion errors). Note that, although these findings are primarily consistent with a retrieval deficit, we cannot definitively rule out the possible contribution of deficient encoding given the quasi-experimental design of the current study.

It was originally hypothesized that the HIV-1 group would demonstrate particular impairment on TB relative to EB tasks given the additional cognitive demands of the former, which potentially imposes greater demands on self-initiated retrieval. However, the present study revealed HIV-1-associated deficits on both TB and EB ProM tasks. ProM failures thus occurred regardless of the specificity of the cue provided, and in essence, thereby crossed the construct barrier of TB versus EB ProM in this sample. This finding provides further support for the notion that deficient executive control of encoding and retrieval is likely driving the ProM failure in this population. To this end, more recent literature calls into question the purported differential sensitivity of TB tasks to fronto-striatal dysfunction associated with normal aging (e.g., Henry et al. 2004) and Parkinson’s disease (Katai et al., 2003). One possibility it that the sensitivity of ProM may relate more specifically to the particular nature of the cue and retrieval processing demands, rather than if the task is time- or event-based (McDaniel et al., 2004).

Post-hoc analyses revealed that Task Substitution errors were more likely to occur on EB trials (d = .72) and were most often characterized by the performance of a repetition from an earlier trial (80%), which suggests the possible influence of interference effects in the retrieval of intentions. In the context of the ProM model, such Task Substitution errors indicate accurate recognition of a ProM cue, but a breakdown in the process of “encoding” (e.g., inaccurate intention-cue associations are initially formed) and/or retrieving the appropriate intention. Experimental studies are needed to further investigate proactive and retroactive interference of ProM cues, including an exploration of the potential effects of the degree of relatedness between cues and intentions (e.g., McDaniel et al., 2004).

ProM—at least as measured by the MIST—demonstrated evidence of construct validity through its associations with well validated clinical tests in the HIV-1 and HC groups. Specific correlations were observed between the MIST and tests of executive functions and verbal working memory, particularly within the HIV-1 sample. Moreover, the relationships between the MIST and learning trials from both the HVLT-R (e.g., semantic clustering) and the BVMT-R provided further evidence of the convergent validity of ProM as an indicator of episodic memory. Although these latter correlations were statistically significant, they were not so strong as to suggest that ProM is too collinear to be of any scientific or clinical interest (i.e., these tasks accounted for less than 30% of the variance in ProM). Preliminary evidence for the divergent validity of ProM was also demonstrated by the absence of significant correlations between the MIST and validated measures of lexical-semantic memory, memory consolidation, or recognition discrimination. Additionally, individuals with HIV-1 infection whose summary scores fell below cutoff were almost eight times as likely to be neuropsychologically impaired, as determined by a broad neuropsychological battery, than those who performed within normal limits. Overall, these data support the construct validity of the component process model of ProM in HIV-1 disease and are consonant with prior research indicating that ProM is related to prefrontal-striatal cognitive functions (e.g., McDaniel, Glisky, Guynn, & Routhieaux, 1999).

One critical question concerns whether our findings represent a true deficit in ProM that is entirely dissociable from retrospective memory (RM) (Einstein & McDaniel, 1990; Ellis, 1996). It is widely held that both ProM and RM are forms of episodic memory, but not necessarily mutually exclusive (Knight, 1998). In fact, ProM requires RM (and thereby medial temporal and limbic structures) as a component process involved in realizing a delayed intention (ProM), such that failures in retrospective recall (i.e., forgetting the content of an intention) will necessarily result in ProM failure (Burgess & Shallice, 1997). In other words, ProM and RM are not doubly dissociable since realizing a delayed intention presupposes a degree of retrospective recall and thereby also depends on the integrity of medial temporal and limbic systems (Dobbs & Reeves, 1996). Although both ProM and RM tasks involve retrieval of an associated event, ProM tasks require subjects to “remember to remember” on their own, without a direct command to search their memory for the appropriate response. In fact, there is clear evidence of a single dissociation between the two abilities (i.e., impaired ProM with intact RM) (e.g., Cockburn, 1996; McDaniel et al., 1999; Shallice & Burgess, 1991), suggesting that clinical assessment of ProM might provide valuable additional information above and beyond that which is offered by RM.

A few important limitations to our findings deserve consideration. Our HIV-1 group was generally healthy in that most of the sample had low plasma viral loads and most were not immunosuppressed, which may restrict generalizability. The relationship between HIV-1 disease severity and ProM therefore remains to be explored (n.b., the current sample did not have adequate variability in disease severity to validly explore such relationships). Future studies might also examine the association between qualitative aspects of ProM performance and neurovirologic (e.g., biomarkers of macrophage activation), neuroimaging, and neuropathologic variables in HIV-1 infection. Also, the present findings are not specific to HIV-infection, nor to conditions with fronto-striatal systems disruption, since ProM deficits are evident in numerous neurologic conditions (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease; Oriani et al., 2003).

One strength of using the MIST to measure ProM was the availability of the 24-hour task, which provided a unique mechanism for expanding a laboratory measure to a more naturalistic setting. Although 24-hour failure rates were high in both the HIV-1 and HC groups, significantly fewer HIV-1 subjects correctly executed the intended action (i.e., telephoning the examiner the day after the evaluation). Although participants were not explicitly instructed to utilize mnemonic cues to enhance task performance (e.g., electronic organizers), the use of such effective strategies was not prohibited. Accordingly, that the HIV-1 sample made significantly more failures on the 24-hour delay task provides additional and ecologically relevant evidence of the pervasiveness of their ProM encoding and retrieval deficits.

To this end, the prevalence of ProM encoding and retrieval failures in our HIV-1 sample potentially carries profound clinical implications in terms of their possible impact on independent living skills (e.g., van den Broek et al., 2000). For instance, prior research shows that HIV-1-associated retrospective learning and memory deficits increase the risk of nonadherence to complex antiretroviral medication regimens (Hinkin et al., 2002). Such findings using retrospective memory tasks imply that assessment and consideration of the ProM deficits associated with HIV-1-infection might further inform advances in the day-to-day management of the disease. In light of the prevalence of Task Substitution errors in HIV-1, it might be prudent to incorporate highly explicit and specific task reminders (e.g., a text messaging system that gives explicit instructions, including the name of the particular medication, recommended dosage, and any conditions under which the medication should be taken) when designing remedial medication adherence strategies. Medication adherence efforts might also be enhanced by minimizing the ProM “load” (e.g., keeping to a minimum the number and complexity of tasks to be completed) for persons with HIV-1.

Footnotes

The research described was also supported by DA12065, MH59745, MH62512, and MH073419 from the National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government. The authors extend their gratitude to Sarah Raskin, Ph.D. for her generosity in supplying a complementary version of the MIST for use in this study. We also thank Jennifer Marquie, Emily Conover, Emily Jo Rajotte, J. Cobb Scott, and Richard Seghers for their assistance with data collection and coding. Aspects of these data were presented as part of a symposium at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society in St. Louis, MO.

References

- Benedict RHB. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benton LA, Hamsher K, Sivan AB. Multilingual aphasia examination. 3. Iowa City, IA: AJA; 1994. Controlled Oral Word Association Test. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Benedict RHB. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—revised. Professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Quayle A, Frith CD. Brain regions involved in prospective memory as determined by positron emission tomography. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:545–555. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Shallice T. The relationship between prospective and retrospective memory: Neuropsychological evidence. In: Conway MA, editor. Cognitive models of memory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1997. pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Grant I, et al. Predictive validity of global deficit scores for detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26:307–319. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn J. Failure of prospective memory after acquired brain damage: Preliminary investigation and suggestions for future directions. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1996;18:304–309. doi: 10.1080/01688639608408284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Jacobson M, Bondi M, Hamilton JM, Salmon DP. The myth of testing construct validity using factor analysis or correlations with normal or mixed populations: Lessons from memory assessment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:936–946. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703960139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Peavy G, Heaton R, Butters N, Salmon DP, Taylor M, et al. Do patients with HIV-associated minor cognitive/motor disorder exhibit a “subcortical” profile? Evidence using the California Verbal Learning Test. Assessment. 1995;2:151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Diehr MC, Heaton RK, Miller SW, Grant I. The Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT): Norms for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1998;5:375–387. doi: 10.1177/107319119800500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs AR, Reeves MB. Prospective memory: More than memory. In: Brandimonte M, Einstein GO, McDaniels MA, editors. Prospective memory: Theory and application. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Normal aging and prospective memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;16:717–726. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA, Richardson SL, Guynn MJ. Aging and prospective memory: Examining the influences of self-initiated retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1995;21:996–1007. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.21.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. Prospective memory or the realization of delayed intentions: A conceptual framework for research. In: Brandimonte M, Einstein GO, McDaniel MA, editors. Prospective Memory: Theory and Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Erdfelder E, Faul F, Buchner A. G*Power: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 1996;28:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Everall IP, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Atkinson JH, et al. Cortical synaptic density is reduced in mild to moderate human immunodeficiency virus neurocognitive disorder. Brain Pathology. 1999;9:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladsjo JA, Schuman CC, Evans JD, Peavy GM, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Norms for letter and category fluency: Demographic corrections for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1999;6:147–178. doi: 10.1177/107319119900600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ. Stroop Color and Word Test. Chicago: Stoelting; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Grant I, Butters N, White DA, Kirson D, Atkinson JH, et al. The HNRC 500-Neuropsychology of HIV infection at different disease stages. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1995;1:231–251. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Grant I, Matthews CG. Comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographic corrections, research findings, and clinical applications. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Taylor MJ, Manly JJ. Demographic effects and use of demographically corrected norms with the WAIS-III and WMS-III. In: Tulsky D, et al., editors. Clinical Interpretation of the WAIS-III and WMS-III. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, MacLeod M, Phillips L, Crawford JR. A meta-analytic review of prospective memory and aging. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:27–39. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Hardy DJ, Lam MN, Mason KI, et al. Medication adherence among HIV + adults: Effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology. 2002;59:1944–1950. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038347.48137.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katai S, Maruyama T, Hashimoto T, Ikeda S. Event based and time based prospective memory in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2003;74:704–709. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.6.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kløve H. Grooved Pegboard. Lafayette, IN: Lafayette Instruments; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Knight RG. Prospective memory. In: Tröster AI, editor. Memory in neurodegenerative disease: Biological, clinical, and cognitive perspectives. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test-64 card computerized version. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kvavilashvili L, Ellis J. Varieties of intentions: Some distinctions and classifications. In: Brandimonte M, Einstein GO, McDaniel MA, editors. Prospective memory: Theory and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Loftus EF. Memory for intentions: The effect of presence of a cue and interpolated activity. Psychonomic Science. 1971;23:315–316. [Google Scholar]

- Massman PJ, Delis DC, Butters N, Levin BE, Salmon DP. Are all subcortical dementias alike? Verbal learning and memory in Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1990;12:729–744. doi: 10.1080/01688639008401015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Glisky EL, Rubin SR, Guynn MJ, Routhieaux BC. Prospective memory: A neuropsychological study. Neuropsychology. 1999;13:103–110. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Guynn MJ, Einstein GO, Breneiser J. Cue-focused and reflexive-associative processes in prospective memory. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;9:1–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.3.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murji S, Rourke SB, Donders J, Carter SL, Shore D, Rourke BP. Theoretically derived CVLT subtypes in HIV-1 infection: Internal and external validation. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:1–16. doi: 10.1017/s1355617703910010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriani M, Moniz-Cook E, Binetti G, Zanieri G, Frisoni GB, Geroldi C, et al. An electronic memory aid to support prospective memory in patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Aging and Mental Health. 2003;7:22–27. doi: 10.1080/1360786021000045863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy G, Jacobs D, Salmon DP, Butters N, Delis DC, Taylor M, et al. Verbal memory performance of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: Evidence of subcortical dysfunction. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1994;16:508–523. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petito CK. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 compartmentalization in the central nervous system. Journal of NeuroVirology. 2004;10:21–24. doi: 10.1080/753312748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. San Antonio, TX: Author; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin S. Memory for intentions screening test [abstract] Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;10(Suppl 1):110. [Google Scholar]

- Reger M, Welsh R, Razani J, Martin DJ, Boone KB. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological sequelae of HIV infection. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:410–424. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shallice T, Burgess PW. Deficits in strategy application following frontal lobe damage in man. Brain. 1991;114:727–741. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek MD, Downes J, Johnson Z, Dayus B, Hilton N. Evaluation of an electronic memory aid in the neuropsychological rehabilitation of prospective memory deficits. Brain Injury. 2000;14:455–462. doi: 10.1080/026990500120556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. Wide Range Achievement Test administration manual. 3. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]