Abstract

To compare regulatory effects of NOS2 in acute and chronic cardiac allograft rejection, we used NOS2 knockout mice as recipients in a cardiac transplant model. To study acute and chronic rejection separately but within the same genetic strain combination, we compared allografts placed into recipients without or with immunosuppression (anti-CD4/8 for 28 days). NOS2 mRNA and protein expression were compared using 32P-RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry. In our acute rejection model, NOS2 was predominately localized to graft-infiltrating immune cells. At day 7, grafts in NOS2-deficient recipients (n = 7) showed reduced inflammatory infiltrates and myocyte damage resulting in significantly lower rejection scores (1.6 ± 0.4) compared to wild-type controls (n = 18; 2.8 ± 0.2, P = 0.002). In contrast, in our chronic rejection model, additional NOS2 expression was localized to graft-parenchymal cells. At day 55, grafts in NOS2-deficient recipients (n = 12) showed more parenchymal infiltration and parenchymal destruction (rejection score 3.8 ± 0.1) than wild-type controls (n = 15; 1.6 ± 0.2, P < 0.0001). This was associated with a significant decrease in ventricular contractility (palpation score 0.3 ± 0.1 compared to 2.3 ± 0.3 in wild-type, P < 0.0001). Hence, NOS2 promotes acute but prevents chronic rejection. These opposing effects during acute and chronic cardiac allograft rejection are dependent on the temporal and spatial expression pattern of NOS2 during both forms of rejection.

Rejection is a complex process involving cellular and humoral immune responses to the challenge of a genetically disparate organ. Allograft rejection is typically classified based on clinical and histopathological patterns. Acute rejection produces rapid graft failure if untreated. Its histological characteristics include infiltrating inflammatory cells, parenchymal and vascular damage, interstitial edema, and hemorrhage. 1 Chronic rejection refers to grafts with protracted functional decline and late graft failure. The histological picture includes parenchymal fibrosis and accelerated transplant arteriosclerosis. 1 Whether acute and chronic rejection are terms describing different phases of the same process, representing independent processes arising from donor/recipient mismatch, or a combination of both remains an open question.

In recent years, the cytokine-inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) has attracted interest as a potential regulator of both acute and chronic rejection. 2,3 However, recent reports have shown that various measures to reduce NOS activity produce contrasting effects in various models of acute and chronic rejection used. For example, in acute rejection studies involving rat cardiac and lung transplant models, pharmacological synthase inhibitors or NO precursors have been shown to attenuate the course of rejection. 4-8 In contrast, in a mouse chronic rejection model where NOS2 is reduced by targeted gene disruption there is accelerated development of graft vasculopathy, the hallmark of chronic rejection. 9 At this point, it remains unclear whether these contrasting results should be attributed to different rejection models or different measures to alter NOS activity or whether they reflect opposing biological effects of NOS2 during acute and chronic rejection.

To study independently the effects of NOS2 on acute and chronic allograft rejection within the same genetic strain combination, we placed MHC class I/II mismatched allografts into recipients with and without T-cell depleting immunosuppressive therapy. 10,11 To assess the effect of NOS2 in these models, we induced a NOS2-deficient state by using recipient mice with targeted deletion of the NOS2 gene. 12 We compared the impact of recipient NOS2-deficiency on ventricular contractility, parenchymal rejection, and intragraft NOS expression in cardiac allografts undergoing acute or chronic rejection placed into NOS2-deficient and wild-type recipients.

Materials and Methods

Mice

For this study, 63 heterotopic cardiac transplantations were studied. This included analysis of 27 chronically rejecting transplants completed as part of another body of work examining arteriosclerotic parameters. 9 Male CBA/CaJ (H-2k) mice (allografts) or C57BL/6J (H-2b) mice (isografts) aged 6 to 8 weeks were used as heart donors. As organ recipients male mice deficient in inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2−/−) on a C57BL/6J × 129SvEv (H-2b) background 12 were compared with wild-type recipients. Two different wild-type strains were used as comparative control groups. The first control group consisted of mosaic B6J129/Sv (H-2b) wild-type recipients (hereafter referred to as B6/129). In addition, we used pure C57BL/6J (H-2b) recipients (hereafter referred to as B6) as a second reference group as this transplantation model had been originally established and characterized with the pure B6 strain combination. 11 NOS2-deficient mice were generously supplied by Dr. Carl Nathan (Cornell University, New York, NY), who produced them in collaboration with J.S. Mudgett. CBA/CaJ (stock number 000654), B6 (stock number 000664) and B6/129 mice (stock number 101045) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME).

Heterotopic Cardiac Transplantation

Vascularized heterotopic abdominal cardiac transplantation was performed as described by Corry et al 10 and transplants were harvested as described previously. 11 Grafts from NOS2−/− recipients were compared with those from wild-type recipients. Acute rejection was studied in allografts placed into nonimmunosuppressed recipients (NOS2−/− n = 7, wild-type B6 n = 10, and wild-type B6/129 n = 8). CBA grafts placed into B6 or B6/129 recipients typically fail by day 8. Hence, grafts were harvested 7 days after transplantation, when the characteristic histological features of acute rejection are maximally developed but before final graft failure, to ensure adequate in vivo perfusion of the graft before tissue harvest and fixation. Chronic rejection was studied in allografts placed into immunosuppressed recipients (NOS2−/− n = 12, wild-type B6 n = 8 and wild-type B6/129 n = 7) that were harvested 55 days after transplantation. At this point, grafts in wild-type recipients developed histological manifestations of chronic rejection with preserved ventricular function (palpation scores ≥ 2).

Immunosuppressive therapy to delay onset of rejection and produce grafts undergoing chronic rejection included anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies (GK1.5 and 2.43; 2.0 mg i.p., days 1–4 and then weekly to day 28) as described previously. 11 As demonstrated by FACS analysis of splenocytes, this program reduces CD4+ and CD8+ cells by >94% during the treatment. 11 At day 55 after transplantation, splenic CD4+ cells were 48% of the control level and CD8+ were 15% of the control level, indicating ongoing low-level immunosuppression. Native hearts from transplanted recipients (NOS2−/− and wild-type) exposed to the same circulation were used as one control group. Isografts placed into untreated recipients (NOS2−/− and wild-type) and exposed to the same surgical procedure were used as a second control group. Graft function was evaluated daily by measuring the force of palpable heart beat and assigning a score ranging from 0 (no palpable heart beat) to 4 (maximal strength heart beat).

Histological Analysis of Rejection

After perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cardiac allografts were harvested at 7 days (acute rejection) or 55 days (chronic rejection) post-transplantation. Transverse heart sections were fixed in Methyl Carnoy’s solution and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Verhoeff’s elastin for histological evaluation. Slides were examined by light microscopy and allografts were graded for severity of rejection using a modified International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation grading system on a scale of 0 (no rejection) to 4 (severe rejection). 13 Grading was performed by two independent observers in a blinded fashion. Scores are reported as mean value for all grafts in each recipient group.

Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Relative gene transcript levels for NOS2 were measured using RT-PCR as published previously. 11 This method allows triplicate analysis of 5 to 11 representative grafts from each group simultaneously. The cDNA panel was prepared from the following hearts: native hearts (wild-type B6 n = 8, NOS2−/− n = 11), isografts (wild-type B6 n = 6, NOS2−/− n = 5), acutely rejecting allografts (wild-type B6 n = 8, NOS2−/− n = 7) and chronically rejecting allografts (wild-type B6 n = 7, NOS2−/− n = 11). Primer sequences, sequence accession numbers, annealing temperatures, and cycle numbers were as follows:

|

Triplicate samples were amplified using the following thermal cycling parameters: denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at a primer-optimized temperature for 20 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 60 seconds (increased by 2 seconds/cycle) followed by a final extension of 7 minutes at the end of all cycles. 32P-dCTP (150,000 cpm/reaction) was included for quantitative PCR studies. The amount of incorporated 32P-dCTP in amplified product bands from dried agarose gels was measured by volume integration (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The corrected level of the specific product was derived by dividing the amplified product value by the mean value for the control gene G3PDH in the respective sample.

Immunohistological Analysis

To localize NOS2 expression within the rejecting hearts, immunostaining for NOS2 was performed in paraffin sections (4 μm) from acutely and chronically rejecting allografts transplanted into wild-type recipients. Polyclonal rabbit anti-NOS2 (1:250, 60 minutes at room temperature) was prepared by Jeffrey R. Weidner and Richard A. Mumford (Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ) and kindly provided to us by Carl Nathan. 14 Negative controls included omission of primary or secondary antibody and staining of native heart sections from NOS2−/− mice.

Statistical Analysis

For comparison of two groups, an unpaired t-test was used. A probability value < 0.05 was considered significant. For comparison of more than two groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. If the ANOVA was significant, the Bonferroni/Dunn procedure was used as a post hoc test. Group data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

NOS2 mRNA and Protein Expression in Acutely and Chronically Rejecting Allografts

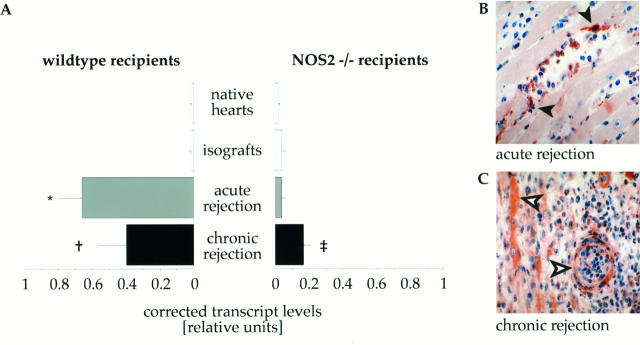

As shown in Figure 1A ▶ , acute rejection was associated with significant induction of NOS2 gene transcript levels in allografts from wild-type recipients (0.66 ± 0.08 relative units) compared with native hearts (0.01 ± 0.01 relative units, P < 0.0001) and isografts (0.02 ± 0.01 relative units, P < 0.0001). In contrast, in acutely rejecting allografts placed into NOS2−/− recipients NOS2 transcript levels (0.04 ± 0.01 relative units) did not show a significant increase when compared to the baseline levels in native hearts (0.02 ± 0.01 relative units, P = 0.24) or isografts (0.04 ± 0.01 relative units, P = 0.87). During chronic rejection, grafts placed into wild-type recipients showed significantly increased NOS2 transcript levels (0.40 ± 0.08 relative units) when compared to baseline levels in native (P < 0.0001) or isograft (P < 0.0002) controls. However, this increase was significantly smaller than in acutely rejecting hearts (P = 0.003). Interestingly, chronically rejecting grafts placed into NOS2−/− recipients (0.17 ± 0.02 relative units) also showed a significant increase in NOS2 transcript levels when compared to native hearts (P < 0.0001), isografts (P < 0.0001) as well as acutely rejecting allografts (P < 0.0001). However, this induction during chronic rejection was significantly lower than in wild-type recipients (P = 0.0034). Thus, disruption of recipient sources of NOS2 resulted in completely abolished intragraft transcript levels of NOS2 during acute rejection, whereas during chronic rejection, grafts in NOS2-deficient recipients still show partially conserved induction of NOS2 expression.

Figure 1.

NOS2 expression (mRNA and protein) in acutely and chronically rejecting allografts. A: Corrected mRNA levels were measured in native host hearts (wild-type n = 8, NOS2−/− n = 11), isografts (wild-type n = 6, NOS2−/− n = 5), acutely (wild-type n = 8, NOS2−/− n = 7) and chronically (wild-type n = 7, NOS2−/− n = 11) rejecting allografts. Reverse-transcriptase 32P-PCR amplification was normalized against G3PDH. Each bar represents the mean ± SD from all cDNAs in each subgroup. * P < 0.0001 acute versus native and isograft, † P < 0.0001 chronic versus native, P = 0.0002 chronic versus isograft, P = 0.003 chronic versus acute, ‡ P < 0.0001 chronic versus native, isograft and acute. Representative photomicrographs (original magnification, ×200) showing inducible nitric oxide synthase gene product in acutely (B) and chronically (C) rejecting mouse cardiac allografts after immunostaining. B: Myocardium of an acutely rejecting allograft showing NOS2 predominantly expressed in infiltrating inflammatory cells (filled arrowheads) . C: Myocardium in a chronically rejecting allograft with NOS2 expression in parenchymal cells (cardiac myocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, open arrows) as well as immune cells.

Immunostaining was performed to localize NOS2 protein expression within acutely and chronically rejecting allografts. In acutely rejecting hearts from wild-type recipients (Figure 1B) ▶ , NOS2 expression was predominantly found in infiltrating macrophages and lymphocytes. It was absent in donor-derived parenchymal cells (vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, or myocytes). In acutely rejecting grafts from NOS2−/− recipients, NOS2 immunopositivity was absent in both infiltrating inflammatory cells and parenchymal cells (data not shown). In chronically rejecting hearts from wild-type recipients (Figure 1C) ▶ , NOS2-expression was induced in cardiac myocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells. This was in addition to the expression in immune cells. Despite the recipient deficiency, NOS2 expression was also evident only in parenchymal cells in grafts from NOS2−/− recipients. As expected, infiltrating inflammatory cells stained negative in these grafts (data not shown).

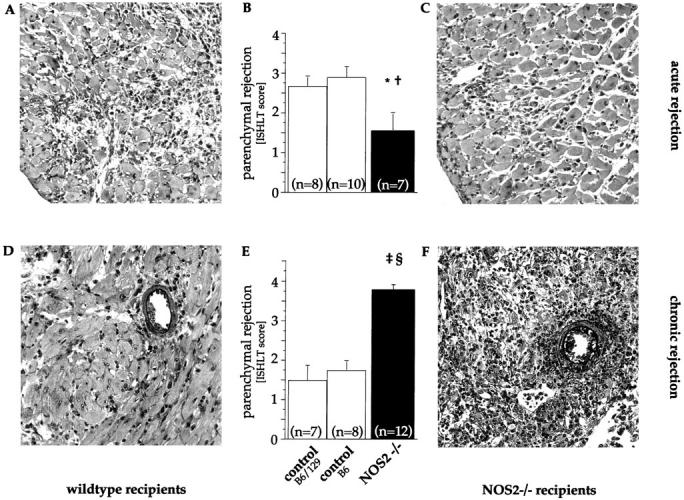

NOS2 Promotes Acute Rejection

As shown in Figure 2A ▶ , at day 7 after transplantation, allografts placed into untreated wild-type recipients (B6 n = 10, B6/129 n = 8) had multifocal inflammatory infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes and macrophages. The allograft parenchyma showed patches of myocyte damage and necrosis (Figure 2A) ▶ . There were no differences between grafts placed into B6 and B6/129 controls. In contrast, allografts placed into untreated NOS2−/− recipients (n = 7) showed only sporadic foci with fewer infiltrating mononuclear cells. The parenchymal architecture was preserved showing only infrequent myocyte damage (Figure 2C) ▶ . This resulted in significantly lower mean histological grading scores (Figure 2B) ▶ in allografts placed into NOS2-deficient recipients (1.6 ± 0.4) compared to those in either wild-type control group (wild-type B6 2.9 ± 0.2, P = 0.002; wild-type B6/129 2.7 ± 0.3, P = 0.012). Scores for the pure and mosaic wild-type recipient groups were not significantly different. Hence, in our acute rejection model the reduction in rejection scores in grafts from nonimmunosuppressed NOS2−/− recipients indicates that NOS2 promotes parenchymal destruction in the acutely rejecting heart.

Figure 2.

Parenchymal rejection in allografts undergoing acute or chronic rejection. Representative sections (Verhoeff’s elastin stain, original magnification, ×30) and mean histological grades of cellular rejection from acutely and chronically rejecting allografts placed in wild-type and NOS2−/− recipients. Sections of myocardium from acutely rejecting 7-day-old allografts placed into a wild-type (A) and NOS2−/− (C) recipient showing reduced myocyte damage in NOS2-deficient recipients. This results in significantly lower mean parenchymal rejection scores (B). In contrast, sections of myocardium from chronically rejecting 55-day-old allografts placed into a wild-type (D) and NOS2−/− (F) recipient showing increased diffuse inflammatory infiltrates and myocyte necrosis, advanced interstitial fibrosis, and scattered interstitial hemorrhage in NOS2-deficient recipients. This results in significant increases in histological grades of rejection (E). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM from all allografts in each subgroup. * P = 0.012 NOS2−/− versus wild-type B6/129, † P = 0.002 NOS2−/− versus wild-type B6, ‡ P < 0.0001 NOS2−/− versus wild-type B6/129, § P < 0.0001 NOS2−/− versus wild-type B6.

NOS2 Prevents Chronic Rejection

Immunosuppressed wild-type recipients produced allografts with sparse interstitial fibrosis, inflammatory infiltrates, and rare myocyte damage (Figure 2D) ▶ . In contrast, allografts placed into immunosuppressed NOS2−/− recipients showed more diffuse inflammatory infiltrates, frequent patches of myocyte necrosis, advanced interstitial fibrosis, and scattered interstitial edema and hemorrhage (Figure 2F) ▶ . As shown in Figure 2E ▶ , mean histological grading scores were significantly higher in allografts from NOS2-deficient recipients (3.8 ± 0.1 [NOS2−/−] compared with those in allografts from wild-type recipients 1.8 ± 0.2 [wild-type B6; P < 0.0001] or 1.5 ± 0.4 [wild-type B6/129; P < 0.0001]). Of note, all grafts in each group showed diffusely diseased vessels. However, as previously established in another set of transplants, 9 NOS2-deficiency of the recipient resulted in increased severity of transplant arteriosclerosis.

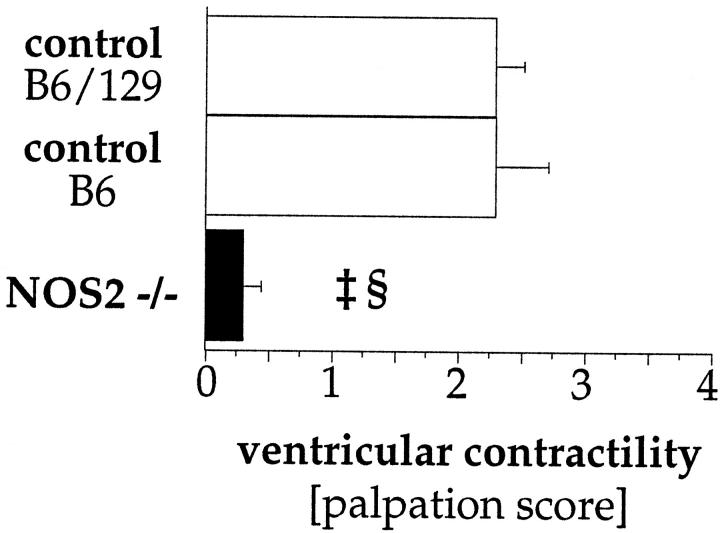

NOS2 Protects Long-Term Graft Function

The impact of NOS2-deficiency on myocardial function was estimated by scoring the force of the palpable heartbeat in chronically rejecting grafts (55 days). As shown in Figure 3 ▶ , mean palpation scores in chronically rejecting grafts placed into NOS2−/− recipients (n = 12) were significantly lower (0.3 ± 0.1) than scores for both wild-type control groups (B6 [n = 8] 2.3 ± 0.4, P < 0.0001; B6/129 [n = 7] 2.3 ± 0.2, P < 0.0001). Similar palpation (chronic rejection) and rejection (acute and chronic rejection) scores in allografts from both wild-type control groups (B6 and B6/129) suggest a comparable alloimmune reponse in these inbred strains.

Figure 3.

Ventricular function in allografts undergoing chronic rejection. In chronically rejecting grafts, NOS2-deficiency results in significant reductions in ventricular palpation scores. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM from all allografts in each subgroup. ‡ P < 0.0001 NOS2−/− versus wild-type B6/129, § P < 0.0001 NOS2−/− versus wild-type B6.

Discussion

We used recipient mice with targeted deletion of the NOS2 gene to show that NOS2 plays different roles in the acute and chronic forms of cardiac rejection. During acute rejection, NOS2 expressed by recipient-derived graft-infiltrating inflammatory cells (lymphocytes and macrophages) promotes a destructive alloimmune response that culminates in rapid graft failure. This was demonstrated by reduced parenchymal rejection in grafts placed into non-immunosuppressed NOS2-deficient recipients. In marked contrast, during chronic rejection (produced by T-cell-depleting immunosuppression), NOS2 is also induced in donor-derived parenchymal cells (myocytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells). Chronically rejecting grafts placed into NOS2-deficient recipients show deteriorated graft contractile function and increased histological grades of rejection. Hence, NOS2 attenuates graft destruction and protects graft function in chronic rejection.

NO, NOS2, and Acute Rejection

The observed reduction in allograft rejection in NOS2-deficient recipients extends previous findings in other acute rejection models correlating pharmacologic inhibition of NOS with prolonged allograft survival and reduced histological grades of rejection. 4-6,8 Immune cell-derived NOS2 mediates destructive effects on the allograft parenchyma. NO may be directly inducing morphological damage to cardiac myocytes. Increased NO synthesis has been associated with an increase in myocyte death. This effect could be prevented by addition of a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. 15 Programmed cell death (apoptosis) has been recognized as one of the causes of NO-mediated cardiac myocyte loss in the transplanted heart. 16 In situ detection of apoptotic myocytes paralleled NOS2 expression in a rat model of cardiac rejection. 16 In vivo gene transfection of endothelial NOS into rat cardiac myocytes has been shown to induce apoptotic cell death, an effect which could be abolished by pretreatment with a NOS inhibitor. 17

NO, NOS2, and Chronic Rejection

With regard to chronic rejection, this study represents the first in vivo assessment of NOS2-mediated actions on parenchymal parameters. NOS2-deficiency resulted in lower palpation scores, more graft destruction with higher rejection scores, and more vascular thickening. This demonstrates that NOS2 has a protective role against ventricular failure in chronically rejecting allografts. The mechanisms for this protective effect deserve further study. Our leading hypothesis is that antiproliferative effects of NO produced by up-regulation of NOS2 in the donor vasculature 18 mediate the protective effects in the transplanted myocardium. In the future, the role of donor-derived NOS2 sources could be further addressed by using NOS2-knockout mice as donors after an appropriate immunosuppressive regimen for the immunogenetically different reverse strain combination (H-2b into H-2k) is identified.

Recently, we showed that NOS deficiency was associated with an increase in the severity of transplant arteriosclerosis. 9 Comparison of arteriosclerotic lesion development in grafts placed into NOS2−/− and wild-type recipients showed a twofold increase in severity of luminal occlusion in association with NOS2-deficiency. Myocyte necrosis, interstitial edema, and mononuclear infiltration characteristic of parenchymal rejection are hard to distinguish from ischemic injury. Attenuation of transplant-associated lesion development in the chronically rejecting allograft would reduce ischemic myocardial damage. We showed that NOS2 deficiency correlates with increases in rejection scores and arteriosclerotic severity. It is believed that the fibrotic parenchymal changes in chronically rejecting hearts result, at least in part, from ischemic insults from diffuse, obliterative vascular thickening. 19 Therefore, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that by maintaining vessel patency, NOS2-mediated anti-arteriosclerotic effects would result in less ischemic damage.

Conclusion

The present study shows contrasting effects of NOS2 on regulation of acute and chronic alloimmune reponses. In our model, a promoting role in the acutely rejecting graft is contrasted by protective effects during chronic rejection. NOS2 expression by graft-infiltrating cells predominates during acute rejection, whereas NOS2 is also induced within parenchymal cells during chronic rejection. The dual effects in these two forms of rejection arise, in part, from the cellular origins of NOS2. However, it is likely that NO effects are determined more by the target cells that are subject to NO actions (myocytes in acute rejection and smooth muscle cells in chronic rejection). The challenge ahead is to characterize these target-specific mechanisms of NO. In the future, selective control may alter the clinical outcome in different stages of allograft rejection.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Mary E. Russell, Cardiovascular Biology Laboratory, Harvard School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: russell@cvlab.harvard.edu.

Supported by a grant of the Milton Foundation and the Abraham Fund. JK was supported by a fellowship grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn, Germany.

References

- 1.McManus BM, Winters GL: Pathology of heart allograft rejection. Kolbeck PC Markin RS McManus BM eds. Transplant Pathology: Clinical and Anatomical Principles. 1994, :pp 197-218 ASCP Press, Chicago [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang X, Chowdhury N, Cai B, Brett J, Marboe C, Sciacca RR, Michler RE, Cannon PJ: Induction of myocardial nitric oxide synthase by cardiac allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1994, 94:714-721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell ME, Wallace AF, Wyner LR, Newell JB, Karnovsky MJ: Upregulation and modulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat cardiac allografts with chronic rejection and transplant arteriosclerosis. Circulation. 1995, 92:457-464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worrall NK, Lazenby WD, Misko TP, Lin TS, Rodi CP, Manning PT, Tilton RG, Williamson JR, Ferguson TB, Jr: Modulation of in vivo alloreactivity by inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1995, 181:63-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winlaw DS, Schyvens CG, Smythe GA, Du ZY, Rainer SP, Lord RS, Spratt PM, Macdonald PS: Selective inhibition of nitric oxide production during cardiac allograft rejection causes a small increase in graft survival. Transplantation 1995, 60:77-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiraishi T, DeMeester SR, Worrall NK, Ritter JH, Misko TP, Ferguson TB, Jr, Cooper JD, Patterson GA: Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase ameliorates rat lung allograft rejection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995, 110:1449-1459;discussion 1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul LC, Myllarniemi M, Muzaffar S, Benediktsson H: Nitric oxide synthase inhibition is associated with decreased survival of cardiac allografts in the rat. Transplantation 1996, 62:1193-1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worrall NK, Boasquevisque CH, Botney MD, Misko TP, Sullivan PM, Ritter JH, Ferguson TB, Jr., Patterson GA: Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase ameliorates functional and histological changes of acute lung allograft rejection. Transplantation 1997, 63:1095-1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koglin J, Glysing-Jensen T, Mudgett JS, Russell ME: Exacerbated transplant arteriosclerosis in inducible nitric oxide-deficient mice. Circulation 1998, 97:2059-2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS: Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation 1973, 16:343-350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Räisänen-Sokolowski A, Glysing-Jensen T, Mottram PL, Russell ME: Sustained anti-CD4/CD8 blocks inflammatory activation and intimal thickening in mouse heart allografts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997, 17:2115-2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacMicking JD, Nathan C, Hom G, Chartrain N, Fletcher DS, Trumbauer M, Stevens K, Xie QW, Sokol K, Hutchinson N, Chen H, Mudgett JS: Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase [published erratum appears in Cell 1995, 81: following 1170]. Cell 1995, 81:641-650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billingham ME, Cary NR, Hammond ME, Kemnitz J, Marboe C, McCallister HA, Snovar DC, Winters GL, Zerbe A: A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart and lung rejection: Heart Rejection Study Group. The International Society for Heart Transplantation. J Heart Transplant. 1990, 9:587-593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie QW, Cho HJ, Calaycay J, Mumford RA, Swiderek KM, Lee TD, Ding A, Troso T, Nathan C: Cloning and characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase from mouse macrophages. Science 1992, 256:225-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinsky DJ, Cai B, Yang X, Rodriguez C, Sciacca RR, Cannon PJ: The lethal effects of cytokine-induced nitric oxide on cardiac myocytes are blocked by nitric oxide synthase antagonism or transforming growth factor β. J Clin Invest 1995, 95:677-685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szabolcs M, Michler RE, Yang X, Aji W, Roy D, Athan E, Sciacca RR, Minanov OP, Cannon PJ: Apoptosis of cardiac myocytes during cardiac allograft rejection. Relation to induction of nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 1996, 94:1665-1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaguchi H, Shin WS, Wang Y, Inukai M, Kato M, Matsuo-Okai Y, Sakamoto A, Uehara Y, Kaneda Y, Toyo-oka T: In vivo gene transfection of human endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in cardiomyocytes causes apoptosis-like cell death: identification using Sendai virus-coated liposomes. Circulation 1997, 95:2441-2447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loscalzo J, Welch G: Nitric oxide and its role in the cardiovascular system. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1995, 38:87-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul LC, Fellstrom B: Chronic vascular rejection of the heart and the kidney–have rational treatment options emerged? Transplantation 1992, 53:1169-1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]