Abstract

Mature podocytes are regarded as growth-arrested cells with characteristic phenotypic features that underlie their function. To determine the relationship between cell cycle regulation and differentiation, the spatiotemporal expression of cyclin A, cyclin B1, cyclin D1, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) p27 and p57, and markers of differentiating podocytes in developing human kidneys was investigated by immunohistochemistry. In S-shaped body stage, Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker that labels the G1/S/G2/M phase, was expressed in the majority (more than 80%) of presumptive podocytes, along with cyclin A (∼20% of the Ki-67-positive cells) and cyclin B1 (less than 5% of Ki-67-positive cells) expression. Among these cells, cyclin D1 and CKIs were markedly down-regulated. At the capillary-loop stage, by contrast, CKIs and cyclin D1 were intensely positive in podocytes, whereas no Ki-67, cyclin B1, or cyclin A expression was seen. Moreover, double-immunolabeling and serial-section analysis provided evidence that CKIs and markers specific for differentiating podocytes, namely PHM-5 (podocalyxin-like protein in humans), synaptopodin (a foot process-related protein), and C3b receptor, were co-expressed at the capillary-loop stage. Podocytes were the only cells within the glomeruli that expressed CKIs at immunohistochemically detectable levels. Furthermore, bcl-2 (an apoptosis inhibitory protein) showed a reciprocal expression pattern to that of CKI. These results suggest that 1) the cell cycle of podocytes is regulated by cyclin and CKIs, 2) CKIs may act to arrest the cell cycle in podocytes at the capillary-loop stage, and 3) the specific cell cycle system in podocytes may be closely correlated with their terminal differentiation in humans.

Podocytes in mature kidneys are regarded as growth-arrested cells with a minimal capacity for cell replication. It has been shown that podocytes in normal rats or rats with various glomerular diseases do not incorporate thymidine. 1-3 We previously observed that podocytes do not increase in number even when the glomerular volume was increased seven-fold in uninephrectomized young rats. 4 These observations suggested that the cell cycle of mature podocytes is stably regulated and may not undergo cell proliferation even in the diseased state. This characteristic biological feature of podocytes may be involved in maintaining stable glomerular function (ie, capillary support and filtration). 5 In the diseased kidney, podocytes show minimal mitosis with an increase in ploidy, suggesting failure to undergo cytokinesis after mitosis. 6,7 The response to cell injury of podocytes may result in progressive glomerulosclerosis. 3,4,8,9 Hence, an understanding of cell cycle regulation in podocytes may help clarify their role in glomerular pathophysiology.

The podocyte lineage originates from nephrogenic mesenchymal cells, which initially form mesenchymal condensates. The cells then transform into epithelial cells during the comma-shaped body stage to the S-shaped body stage, into which capillaries invade. 10 During these stages, podocytes occasionally display mitotic figures. In the next glomerular stage, called the capillary-loop stage, podocytes develop foot processes, indicating that phenotypic expression of terminal differentiation has just started. 11 Bustling cell cycle alteration in the podocytes has been shown to occur during this nephrogenic process. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is expressed strongly in podocytes at the S-shaped body stage, and this expression is dramatically reduced at the capillary-loop stage in human fetal kidneys, indicating a rapid arrest of the podocyte cell cycle during nephrogenesis. 12 Furthermore, podocytes in mature glomeruli do not express PCNA or incorporate thymidine. 1,12 Thus, the mechanism responsible for the cell cycle arrest that occurs during nephrogenesis may also participate in maintenance of cell cycle quiescence in mature podocytes.

The mammalian cell cycle is governed by a balance of positive and negative cell cycle regulatory proteins, namely, the cyclins and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs), respectively. 13 Cyclin D and cyclin E are responsible for the progression of the G1/S phase, and the S/G2/M phase is promoted by cyclin A and cyclin B. These cell cycle activators are negatively regulated by the CKIs, which include p21WAF1/CIP1 (p21 in this manuscript), p27Kip1 (p27), and p57Kip2 (p57). 13

Thus, we have investigated the expression of cell cycle proteins in the human podocyte lineage where dramatic cell cycle alterations have been shown to occur. 12 Furthermore, to test the hypothesis that podocyte differentiation is controlled under cell cycle quiescence, the co-expression of CKIs and markers of podocyte differentiation was analyzed. Our findings suggest that CKIs may be important determinants of cell cycle regulation and of terminal differentiation in the podocyte lineage.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Fetal Kidneys

Twenty-six human fetal kidneys (10 weeks to 41 weeks of gestational age; 3 cases of <14 weeks, 4 cases at 19 weeks, 4 cases at 24 weeks, 5 cases at 30 weeks, 5 cases at 34 weeks, and 5 cases at >35 weeks) from either autopsy or abortions were adopted for immunohistochemical staining. Kidneys were fixed with either 10% paraform aldehyde or ethanol and then embedded in paraffin. Snap-frozen kidneys were also preserved until use. Cases in which renal anomalies were evident were not included, and all materials were well preserved for immunohistochemical analysis.

Antibodies

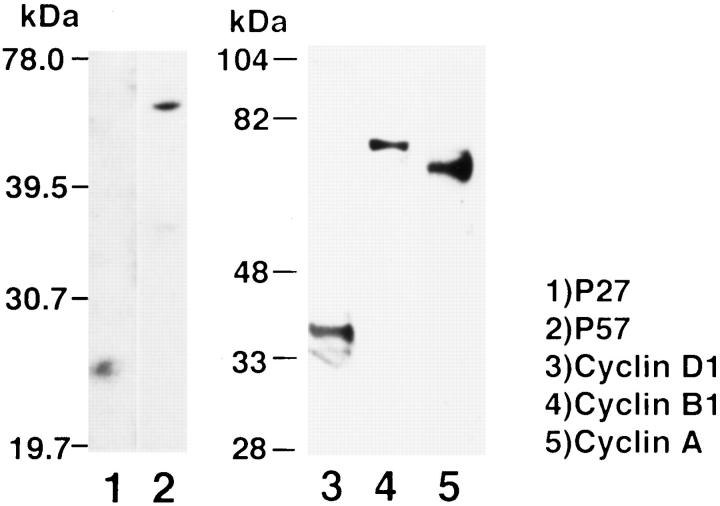

Table 1 ▶ shows profiles of and references for the antibodies used in this study. Western blot analysis was used to confirm specific reactivity of the antibodies against cell cycle proteins exactly as previously described. 14 Briefly, proteins were extracted from rat brain (for antibody against p27 and p57) or human mesangial cells (for antibody against cyclins) using the previously described extraction buffer containing 50 mmol/L glycerophosphate, pH 7.3, 1.5 mmol/L EGTA, 0.1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 1 mmol/L benzamidine. Each protein was resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the proteins were then transferred to an Immobilon P membrane (Daiichikagaku, Tokyo, Japan). The membrane was then incubated with each antibody in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.5% Tween 20 for 2 hours at 37°C and then visualized using the ECL chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK). As shown in Figure 1 ▶ , antibodies against p27 and p57 showed specific reactivity for a protein of expected molecular weight, and no cross-reactivity between these two antibodies was seen. Cyclin D1, cyclin B1, and cyclin A also showed specific reactivity on Western blot analysis. The specificity of the other antibodies has been well established (Table 1) ▶ .

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemical Staining

| Antibodies | Localization in mature podocyte | Species (clone or immunization) | Dilution | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki-67 | Negative | Mouse MAb (clone MIB1) | 1/100 | MBL | 39 |

| Cyclin A | Negative | Rabbit pAb (aa.1–432 of human cyclinA) | 1/500 | Santa Cruiz Bio Tec | 41 |

| Cyclin B1 | Negative | Mouse MAb (human recombinant cyclin B1) | 1/1000 | Santa Cruiz Bio Tec | 42 |

| Cyclin D1 | Nuclei | Mouse MAb (aa.1–295 of human cyclin D1) | 1/100 | Santa Cruiz Bio Tec | NA |

| p27 | Nuclei | Mouse MAb (clone 57) | 1/200 | Transduction Lab | 43 |

| p57 | Nuclei | Rabbit pAb (aa.286–305 of c-terminus Kip2 p57) | 1/100 | Santa Cruiz Bio Tec | NA |

| PHM-5 | Membrane | Mouse MAb (PHM-5) | Sup | Dr. Atkins | 17 |

| Synaptopodin | Foot process | Mouse MAb (pp44) | Sup | Dr. Mundel | 18 |

| C3b-receptor | Membrane | Mouse MAb (Tod5) | ×50 | Dako | 19 |

| WT1 | Nuclei | Rabbit PAb (peptide of the Wilm’s tumor protein) | ×300 | Santa Cruiz Bio Tec | 44 |

| bcl-2 | Cytoplasm | Mouse MAb (clone 124) | ×100 | Dako | 45 |

Sup, supernatant of the hybridoma; MAb, monoclonal antibody; PAb, polyclonal antibody, aa, amino acid; NA, not available.

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis demonstrating specificity of the antibodies against cell cycle proteins. Ten micrograms of protein extracted from rat brain was loaded in lanes 1 and 2 and immunoblotted with antibodies to p27 and p57, respectively. No cross-reactivity between these two antibodies is noted. In lanes 3, 4 and 5, 20 μg of protein extracted from human mesangial cells was immunoblotted with antibodies to cyclin D1, cyclin B1, and cyclin A, respectively. Specific immunoreactive bands are obtained and are consistent with the molecular weight of each cyclin. Molecular weight markers in kilodaltons are shown in the margin.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on serial sections, using the streptavidin and biotin technique, as described previously. 15 For Ki-67 (a cell proliferation marker that labels the G1/S/G2/M phase), cyclin A, cyclin D1, cyclin B1, p27, and bcl-2 (an apoptosis inhibitory protein) immunostaining, antigens were retrieved by autoclave pretreatment (120°C for 20 minutes) in citrate buffer (pH 6). The incubation time for antibodies was either 60 minutes at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Immunoreaction products were developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% H2O2. Occasionally, nuclear staining with hematoxylin and counterstaining with periodic acid-Schiff reagent were carried out.

As negative controls for immunostaining, the same procedures were used with the same materials treated with either normal mouse or rabbit serum or PBS alone instead of each first antibody as described previously. 15 Control materials incubated with either normal mouse serum or PBS alone were entirely negative for immunostaining (data not shown).

Immunofluorescence microscopic analyses for the detection of WT1 (a Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene product), synaptopodin (an actin-related protein specific for foot processes), C3b receptor, and p57 were performed by standard procedures that are described elsewhere. 16 A double-immunolabeling technique was performed to determine the co-expression of p57 and either synaptopodin or C3b receptor. Briefly, sections taken from snap-frozen fetal kidneys were fixed with acetone for 10 minutes. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with blocking solution for 30 minutes and then incubated with mixed antibodies against p57 and synaptopodin or p57 and C3b receptor for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with PBS, these sections were incubated with second antibodies composed of fluorescein-isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG mixed with rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Cappel, Durham, NC). Sections were then observed under an immunofluorescence microscope. A negative control was provided by using PBS as a first antibody, and no specific immunoreaction was observed (data not shown).

Results

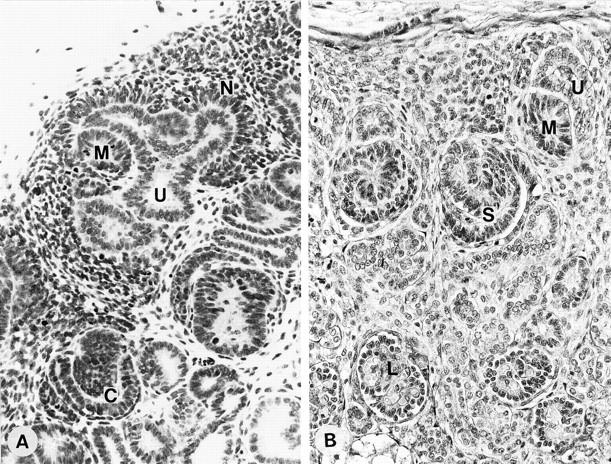

As shown in Figure 2 ▶ , the nephrogenic zone in developing embryonic kidneys displays various stages of glomerular development, which allows the podocyte lineage to be followed. Centrifugal glomerular maturation is well preserved throughout kidney development and it allows us to trace podocyte differentiation even in a single section. The nephrogenic zone was absent in cases of later than 35 weeks of gestation in which all glomeruli are post-capillary-loop stage as has been noted in previous reports. 12

Figure 2.

Light microscopic view of a section from a developing kidney at 11 weeks (A) and 28 weeks (B) of gestation. Both sections have glomeruli at various stages of development in which the podocyte lineage can be observed. Nephrogenic mesenchyme (N) and mesenchymal condensates (M) develop around the ureteric bud (U). The comma-shaped body stage (C), S-shaped body stage (S), and capillary-loop stage (L) can be observed in a single section. Note that podocytes at the S-shaped body stage are closely associated, whereas podocytes at the maturing stage lose these tight attachments. Magnification, ×250 (A) and ×300 (B).

Expression of Ki-67 and Cyclins

Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker that labels G1/S/G2/M phase cells, was expressed in the majority of presumptive podocytes at the comma-shaped and S-shaped body stages. Approximately 80% of the presumptive podocytes expressed Ki-67. This expression was markedly reduced in podocytes at the capillary-loop stage, and no Ki-67 expression was evident at the maturing stage. Cyclin A, an S phase promoter, expression was scattered among presumptive podocytes in every glomerular profile, and the incidence of positive cells in S-shaped body stage was ∼20% of Ki-67-positive cells. Cyclin B1, a positive determinant for the G2/M phase transition, was minimally expressed in presumptive podocytes until the capillary-loop stage, and the incidence of cells positive for cyclin B1 was less than 5% of Ki-67-positive cells.

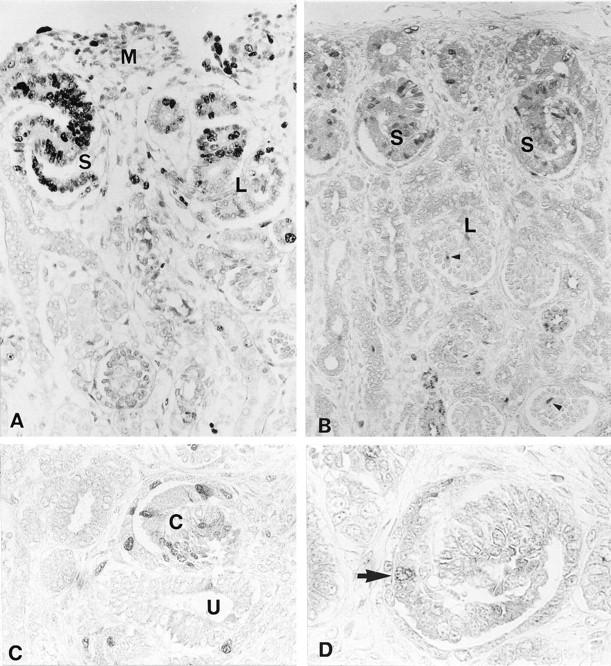

No expression of Ki-67, cyclin A, or cyclin B1 was observed after the capillary-loop stage (Figure 3) ▶ . Distinct expression of cyclin A and cyclin B1 was sometimes observed in mesangial cells, endothelial cells, and parietal epithelial cells after the capillary-loop stage. Cyclin D1, a major promoter of the G1/S transition, was expressed ubiquitously in mature nephrons. In the podocyte lineage, cyclin D1 was expressed in mesenchymal condensates, and then expression was markedly down-regulated during the comma-shaped body and S-shaped body stages. This expression was again increased at the capillary-loop stage. Cyclin D1 and Ki-67 showed reciprocal patterns of expression throughout the podocyte lineage. Although mesangial cells and endothelial cells sometimes showed distinct cyclin D1 immunolabeling after the capillary-loop stage, cyclin D1 was predominantly expressed in the podocytes at this stage (Figure 4) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Expression of Ki-67, cyclin A, and cyclin B1 in fetal kidneys at 24 weeks of gestation. A: Ki-67. Ki-67-positive cells were found scattered in the nephrogenic mesenchyme (M) and frequently at the S-shaped body stage (S). This expression was markedly reduced at the capillary-loop stage (L). Magnification, ×250. B and C: Cyclin A. Cyclin A was expressed in approximately 15% to 20% of presumptive podocytes at the S-shaped body stage (S) and comma-shaped body stage (C), which are identified by the ureteric bud (U). Podocytes at the capillary-loop stage (L) were entirely negative for cyclin A, whereas the endothelial cells or mesangial cells were sometimes positive (arrowhead). Magnification, ×200 (B) and ×250 (C). D: Cyclin B1. Cyclin B1-positive cells are found only infrequently in presumptive podocytes at the comma-shaped body stage (arrowhead). Magnification, ×500.

Figure 4.

Expression of cyclin D1 in the fetal kidney at 11 weeks of gestation. A: Cyclin D1 was initially expressed in mesenchymal condensates (asterisk) and podocytes at the capillary-loop stage. At the comma-shaped body stage (C), cyclin B1 expression was markedly down-regulated. Magnification, ×300. B: In maturing glomeruli, cyclin D1 was clearly positive among podocytes and, to some extent, in mesangial cells and endothelial cells. Magnification, ×300.

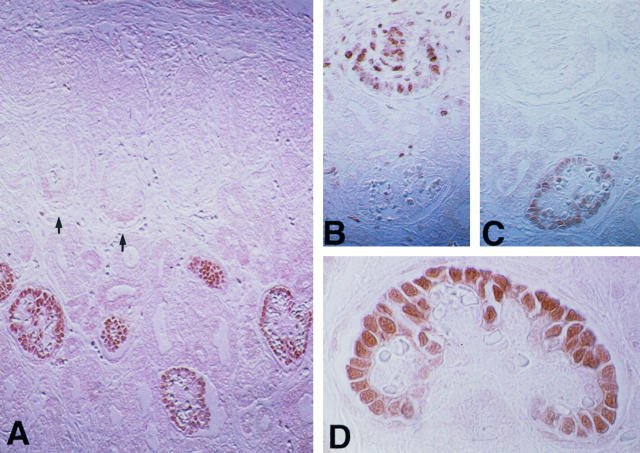

Reciprocal Expression Pattern of Ki-67 and p27

At the capillary-loop and maturing stages, p27 was exclusively and clearly expressed in the nuclei of podocytes. No immunolabeling of p27 was identified in mesenchymal condensates up to the S-shaped body stage. Serial-section analysis revealed reciprocal expression pattern of p27 and Ki-67 occurring in a glomerular-stage-dependent manner. Furthermore, this p27 expression was limited to the podocytes (Figure 5) ▶ . No expression was immunohistologically detectable in mesangial cells, endothelial cells, tubular cells, or parietal epithelial cells.

Figure 5.

Expression of p27 and Ki-67 in the fetal kidney. A: p27 expression in a fetal kidney at 24 weeks of gestation. At the S-shaped body stage (arrow), p27 was not expressed, whereas podocytes at the capillary-loop stage showed diffuse p27 expression. Magnification, ×150. B and C: Serial-section immunostaining for Ki-67 (B) and p27 (C) in fetal kidney at 18 weeks of gestation. Note that the expression of Ki-67 and p27 in podocytes at the S-shaped body stage and the capillary-loop stage were reciprocal. Magnification, ×200. D: Higher-magnification view of glomeruli at the maturing stage. Of note, p27 is expressed in the podocyte nuclei but not in mesangial cells or endothelial cells. Magnification, ×500.

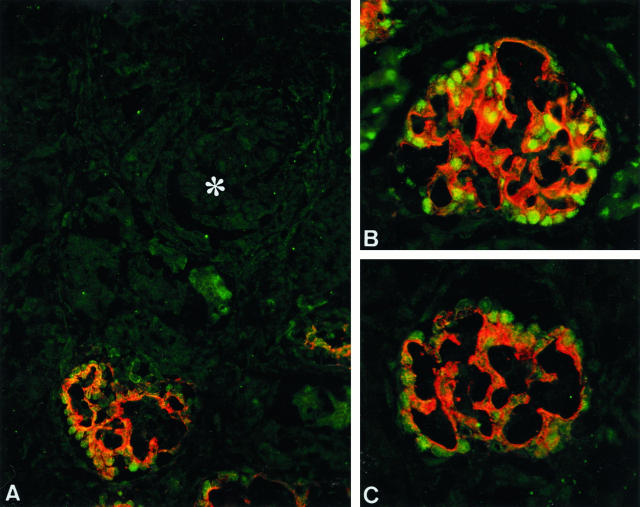

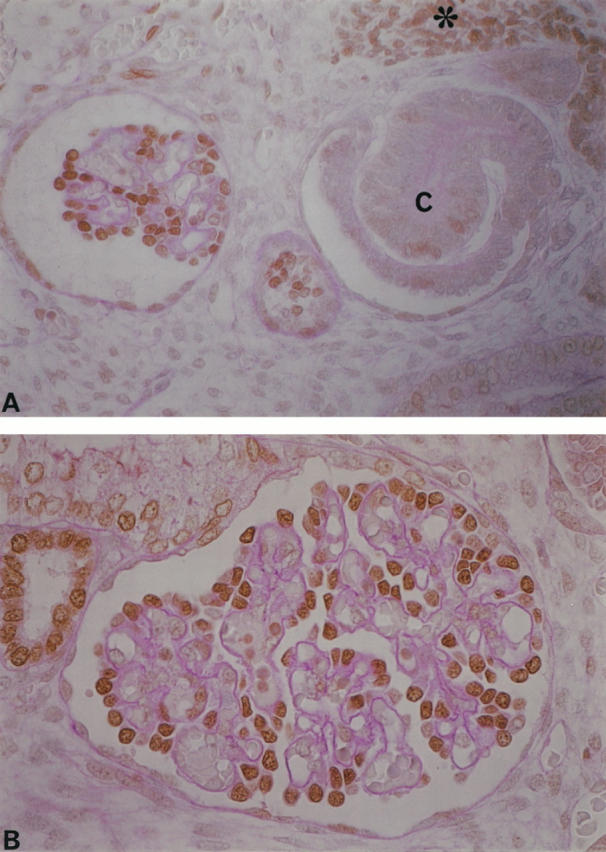

Co-Expression of CKIs and Podocyte Differentiation Markers

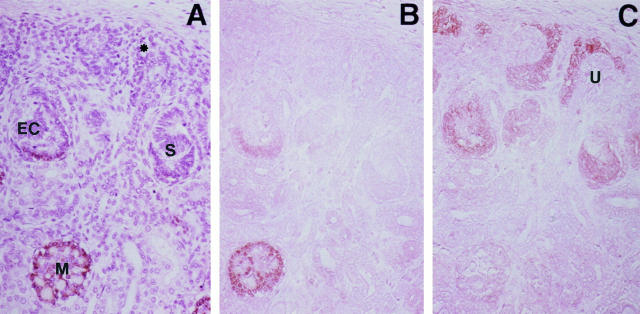

PHM-5 is an antibody that recognizes the apical membrane of human podocytes. 17 Synaptopodin, an actin-related protein, has been found to be specifically localized in the foot processes of podocytes and in telencephalic dendrites. 18 The C3b receptor is expressed in maturing podocytes. 19 These proteins are recognized as functional markers, reflecting the state of differentiation of podocytes. Using a double-immunolabeling technique, we have demonstrated that the co-expression of p57 with synaptopodin and C3b receptor is first detectable at the capillary-loop stage (Figure 6) ▶ . Podocytes in maturing glomeruli showed prominent co-expression of p57 and these differentiation markers. In addition, serial-section analyses showed that PHM-5 is initially expressed with p27 at the capillary-loop stage. Bcl-2, an apoptosis inhibitory protein, is expressed during mesenchymal-epithelial transition in human nephrogenesis. 20 The expression of bcl-2 was markedly reduced after the capillary-loop stage, concurrent with an up-regulation of p27 expression (Figure 7) ▶ . WT1 was expressed throughout the podocyte lineage, and expression became intense after the capillary-loop stage 21 (data not shown).

Figure 6.

A double-immunolabeling technique demonstrated the co-expression of p57 and synaptopodin (A and B) and p57 and C3b-receptor (C). At the S-shaped body stage, neither antibody had a positive reaction (asterisk), whereas podocytes at the capillary-loop stage expressed both p57 and synaptopodin (in fetal kidneys from 24 weeks of gestation). Magnification, ×300. B: Distinct co-expression is observed in maturing glomeruli from fetal kidneys at 35 weeks of gestation. Magnification, ×400. C: Co-expression of p57 and C3b receptor was initially found at the capillary-loop stage. Magnification, ×400.

Figure 7.

Expression of PHM-5 (A), p27 (B), and bcl-2 (C) in serial sections from fetal kidneys at 18 weeks of gestation. Note that mesenchymal condensates (asterisk) surround the ureteric bud (U), and presumptive podocytes at the S-shaped body stage (S) were negative for PHM-5 and p27, whereas bcl-2 was strongly expressed. Expression of PHM-5 and p27 occurred first at the early capillary-loop stage (EC), and the maturing stage (M) exhibited strong expression of p27 and PHM-5, whereas bcl-2 expression was markedly down-regulated. Magnification, ×160.

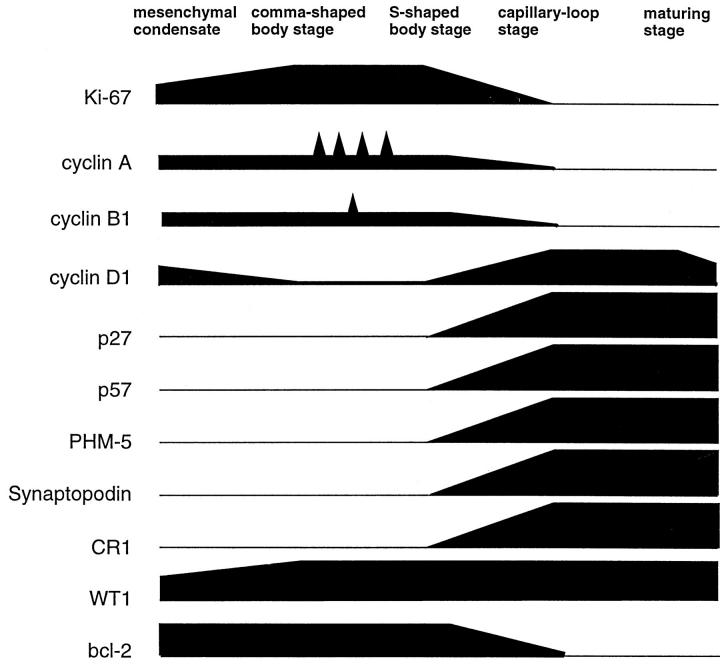

The expression pattern of all of the antibodies in podocytes at each nephrogenic stage is summarized in Figure 8 ▶ .

Figure 8.

Pattern of expression of cell cycle proteins and differentiation markers in developing podocytes. The reciprocal expression and co-expression of several proteins in differentiating podocytes suggests the requirement of protein interactions in podocyte differentiation. The black triangles in cyclin A and cyclin B1 indicate that a proportion of podocytes expressed these proteins.

Discussion

The present study characterized the spatiotemporal expression of cell-cycle-related proteins and podocyte-specific markers in the human podocyte lineage. We previously observed that PCNA was frequently expressed in podocytes at the S-shaped body stage and that this expression was dramatically reduced at the capillary-loop stage, indicating that podocytes rapidly become quiescent at this latter stage. 12 This finding was confirmed by the expression of Ki-67, another marker for cell cycle activation, in this study. A recent report showed the expression of p21 in podocytes from human fetal kidneys. 22 As p21 binds PCNA to suppress the cell cycle, 23 it may be that the rapid cell cycle arrest that occurs in podocytes at the capillary-loop stage was promoted by p21. In addition, the present study provides evidence that two other CKIs, p27 and p57, are initially co-expressed in podocytes at the capillary-loop stage, concurrent with a down-regulation of Ki-67 expression. After the capillary-loop stage, the mesangial cells and endothelial cells sometimes expressed Ki-67, whereas podocytes exhibited no immunohistochemically detectable Ki-67. This expression pattern of p27 in fetal kidney was confirmed by the recent study by Combs et al. 24 A similar pattern of p57 expression to that demonstrated in the present study was also shown in the developing mouse podocytes. 25 These findings suggest that the CKIs act synergistically to arrest the cell cycle at the capillary-loop stage of the podocyte lineage. Furthermore, the persistent expression of CKIs after the maturing stage implies that the CKIs act to keep the cell cycle quiescent in mature podocytes. A recent in vivo functional study by Shankland et al, which analyzed the changes in cell cycle proteins during podocyte injury, supports this hypothesis. 26 They used a rat model of membranous nephropathy and found up-regulation of p21 and p27 and increased binding activity to cyclin A cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)2 complexes. Furthermore, when basic fibroblast growth factor was administered to this model, in which mitosis and ploidy have been shown to increase, p21 expression was decreased in association with increased DNA synthesis in podocytes. Taken together, these results suggest that CKIs may be an important determinant of cell cycle quiescence in podocytes.

Up-regulation of Ki-67 expression in presumptive podocytes until the S-shaped body stage indicates that they are in various phases of the active cell cycle (G1/S/G2/M phase). To specify the phase of cell cycle in the podocyte lineage, the present immunohistochemical study examined the expression of each cell cycle regulatory protein. The G1 phase is positively promoted by cyclin D and CDK complexes. The S phase is mainly promoted by cyclin A, and the subsequent G2/M phase is positively promoted by cyclin B and CDK complexes. 13 The population of each cell cycle stage cell may indicate the time course of the cell cycle in the podocyte lineage. Cyclin A was occasionally positive and cyclin B1 was very rarely positive in presumptive podocytes until the S-shaped body stage, in association with Ki-67. Approximately 80% of presumptive podocytes expressed Ki-67, and not all Ki-67-positive cells expressed cyclins A or B1. Among the Ki-67-expressing cells, ∼20% were cyclin A positive and less than 5% were cyclin B1 positive. This suggests that the majority of Ki-67-positive presumptive podocytes are in G1/S phase. The presence of only a relatively small number of cyclin-A- and cyclin-B1-positive cells may be explained by the fact that they are rapidly degraded by ubiquitin systems. 27 Cyclin A and cyclin B1 were not expressed in podocytes after the capillary-loop stage. Of note, cyclin D1 was apparently down-regulated in these proliferating presumptive podocytes, and then its expression, along with that of the CKIs, was increased and persisted after the capillary-loop stage. As cell cycle activation is determined by the balance of positive and negative cell cycle regulators, cyclin D1 down-regulated presumptive podocytes may be in active cell cycle due to marked down-regulation of CKIs. Taken together, these observations suggest that CKIs regulate the G1/S transition during an active mesenchymal-epithelial transition and podocyte differentiation in the developing human kidney.

The regulatory mechanism of CKI levels in podocytes is unknown. Although degradation by the ubiquitin system may play a role in passive regulation, 27 the factors that determine CKI synthesis in podocytes have not yet been established. Several known factors that show altered expression in podocyte differentiation may provide a clue for the CKI regulation. WT1, a Wilms’ tumor suppresser gene product, has a proline-rich amino terminus that represses the transcription of a number of target promoters. 28 As previously shown, WT1 is expressed throughout the podocyte lineage, and its expression pattern suggests a role for WT1 in podocyte differentiation. 21,29 Microinjection of WT1 cDNA into quiescent cells blocked cell cycle progression to S phase through the inhibition of cyclin/CDK complexes. 30 Furthermore, Englert and colleagues recently demonstrated that WT1 induces p21 expression in Saos-2 cells and observed co-expression of WT1 and p21 in human fetal kidneys, specifically in podocytes. 22 Although these findings may suggest that WT1 is involved in cell cycle arrest in the podocyte lineage via the induction of CKIs, the involvement of WT1 in CKI regulation is still obscure, as expression of WT1 was detectable during CKI down-regulation in actively dividing presumptive podocytes at the S-shaped body stage. Of note is that PAX2 expression was down-regulated concurrent with WT1 up-regulation in the podocyte lineage. 31 Furthermore, PAX2 may stimulate endogenous WT1 gene expression. 32 Interestingly, the pattern of expression of PAX2 is similar to that of bcl-2. 31 Bcl-2 was identified as a gene responsible for follicular lymphoma, which inhibits apoptosis. 33 Bcl-2 was expressed in the nephrogenic zone, 20 and bcl-2-deficient mice showed abnormal renal development, suggesting its indispensable role in kidney development. 34 As demonstrated in the present study, the expression of bcl-2 was up-regulated at the comma-shaped and S-shaped body stages when p27 was not expressed. This may be supported by the recent finding of Upadhyay et al that bcl-2 inhibited p21 expression in breast epithelial cells. 35 Likewise, after the capillary-loop stage, bcl-2 expression was markedly down-regulated concurrent with CKI up-regulation. Interestingly, Hewitt et al demonstrated that WT1 repressed the transcription of bcl-2 promoters in HeLa cells. 36 Additional functional studies are needed to address CKI regulation in the podocyte lineage.

An additional insight provided by the present study was that cell cycle regulation and differentiation in podocytes may be closely related. Double-immunolabeling techniques and serial-section analyses provided evidence that PHM-5, synaptopodin, and C3b receptor were initially co-expressed with CKIs in podocytes at the capillary-loop stage. PHM-5, synaptopodin, and C3b receptor were initially expressed at the capillary-loop stage, where the foot processes developed, indicating that the terminal differentiation of podocytes commences in this stage. As CKIs are distributed in terminally differentiated cells such as myocytes, 37,38 the expression of CKIs in terminally differentiating podocytes at the capillary-loop stage is likely. This hypothesis is strongly supported by experiments utilizing a recently established mouse immortalized podocyte cell line. 39 In this cell line, when cobblestone cells transformed to arborized cells, the cells expressed podocyte-specific synaptopodin with a loss of BrdU incorporation. Thus, it may be concluded that cell cycle quiescence is required for terminal differentiation of podocytes.

In conclusion, the present study has described the expression of cell cycle regulators in the human podocyte lineage. The reciprocal expression pattern of cell proliferative marker and CKIs (p27 and p57) in differentiating podocytes implies that CKIs may play a central role in cell cycle regulation and differentiation in podocytes. The stable and strong expression of CKIs in mature functioning podocytes suggests a requirement for CKIs in cell cycle quiescence to allow for stable glomerular function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Takahashi for providing the materials. We appreciate the generous gifts of antibodies from Drs. P. Mundel (Heidelberg) and R.C. Atkins (Melbourne). Expert technical assistance by S. Horita and S. Shibata is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Michio Nagata, Department of Pathology, Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305-8575, Japan. E-mail: nagatam@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (07670231) and from the University of Tsukuba Research Projects.

References

- 1.Pabst R, Sterzel RB: Cell renewal of glomerular cell types in normal rats: an autoradiographic analysis. Kidney Int 1983, 24:626-631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasch R, Nørgaard JO: Renal enlargement: comparative autoradiographic studies of 3H-thymidine uptake in diabetic and uninephrectomized rats. Diabetologia 1983, 25:280-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fries JU, Sandstrom DJ, Meyer TW, Rennke HG: Glomerular hypertrophy and epithelial cell injury modulate progressive glomerulosclerosis in the rat. Lab Invest 1989, 60:205-218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagata M, Kriz W: Glomerular damage after uninephrectomy in young rats. II. Mechanical stress on podocytes as a pathway to sclerosis. Kidney Int 1992, 42:148-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mundel P, Kriz W: Structure and function of podocytes: an update. Anat Embryol 1995, 192:385-397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagata M, Yamaguchi Y, Komatsu Y, Ito K: Mitosis and presence of binucleate cells among glomerular podocytes in diseased human kidneys. Nephron 1995, 70:68-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kriz W, Hahnel B, Rosner S, Elger M: Long-term treatment of rats with FGF-2 results in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 1995, 48:1435-1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kriz W, Elger M, Nagata M, Kretzler M, Uiker S, Koeppen-Hageman I, Tenchert S, Lemley K: The role of podocytes in the development of glomerular sclerosis. Kidney Int 1994, 45:S-64-S-72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kihara I, Yaoita E, Kawasaki K, Yamamoto T: Limitation of podocyte adaptation for glomerular injury in puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis. Pathol Int 1995, 45:625-634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxen L: The metanephros. Saxen L eds. Organogenesis of the Kidney. 1987, :pp 13-18 Cambridge University Press Cambridge, UK, [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeves W, Caulfield JP, Farquhar MG: Differentiation of epithelial foot processes and filtration slit. Lab Invest 1978, 39:90-100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagata M, Yamaguchi Y, Ito K: Loss of mitotic activity and the expression of vimentin in glomerular epithelial cells of developing human kidneys. Anat Embryol 1993, 187:175-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankland ST: Cell-cycle control and renal disease. Kidney Int 1997, 52:294-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terada Y, Tomita K, Homma MK, Nonoguchi H, Yang T, Yamada T, Yuasa Y, Krebs EG, Sasaki S, Marumo F: Sequential activation of Raf-1 kinase, mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase, MAP kinase, and S6 kinase by hyperosmolality in renal cells. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:31296-31301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagata M, Akioka Y, Tsunoda Y, Komatsu Y, Kawaguch H, Yamaguchi Y, Ito K: Macrophages in childhood IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 1995, 48:527-535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagata M, Watanabe T: Podocytes in metanephric organ culture express characteristic in vivo phenotypes. Histochem Cell Biol 1997, 108:17-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerjaschki D, Poczewski H, Dekan G, Horvat R, Balzar E, Kraft N, Atkins RC: Identification of a major sialoprotein in the glycocalyx of human visceral epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 1986, 78:1142-1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mundel P, Heid HW, Mundel TM, Kruger M, Reiser J, Kriz W: Synaptopodin: an actin-associated protein in telencephalic dendrites and renal podocytes. J Cell Biol 1997, 39:193-204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appay MD, Mounier F, Gubler MC, Rouchon M, Beziau A, Kazatchkine MD: Ontogenesis of the glomerular C3b receptor (CR1) in fetal human kidney. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1985, 37:103-113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeBrun DP, Warnke RA, Cleary ML: Expression of bcl-2 in fetal tissues suggests a role in morphogenesis. Am J Pathol 1993, 142:743-753 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mundlos P, Pelletier J, Darveau A, Bachmann M, Winterpacht A, Zabel B: Nuclear localization of the protein encoded by the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in embryonic and adult tissues. Development 1993, 119:1329-1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Englert CE, Maheswaran S, Garvin AJ, Kreidberg J, Haber DA: Induction of p21 by the Wilms’ tumor suppresser gene WT1. Cancer Res 1997, 57:1429-1434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Jackson PK, Kirschner MW, Dutta A: Separate domains of p21 involved in the inhibition of cdk kinase and PCNA. Nature 1995, 374:386-388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combs HL, Shankland SJ, Setzer SV, Hudkins KL, Alpers CE: Expression of the cyclin kinase inhibitor, p27kip1, in developing and mature human kidney. Kidney Int 1998, 53:892-896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan Y, Friesen J, Lee MH, Massague J, Barbacid M: Ablation of the CDK inhibitor p57Kip2 results in increased apoptosis and delayed differentiation during mouse development. Genes Dev 1997, 11:973-983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shankland ST, Floege J, Thomas SE, Nangaku M, Hugo C, Pippin J, Hennke K, Hockenberry DM, Johnson RJ, Couser WG: Cyclin kinase inhibitors are increased during experimental mambranous nephropathy: potential role in limiting glomerular epithelial cell proliferation in vivo. Kidney Int 1997, 52:1230-1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glotzer M, Murray AW, Kirchner MW: Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature 1991, 349:132-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rauscher FJ, III: The WT1 Wilms tumor gene product: developmentally regulated transcription factor in the kidney that functions as a tumor suppressor. FASEB J 1993, 7:896-903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grubb GR, Yun K, Williams BRG, Eccles MR, Reeve AE: Expression of WT1 protein in fetal kidneys and Wilms’ tumors. Lab Invest 1994, 71:472-479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kudoh T, Ishidate T, Moriyama M, Toyoshima K, Akiyama T: G1 phase arrest induced by Wilms tumor protein WT1 is abrogated by cyclin/CDK complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:4517-4521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dehbi M, Ghahremani M, Lechner M, Dressler G, Pelletier J: The paired-box transcription factor, PAX2, positively modulates expression of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene (WT1). Oncogene 1996, 13:447-453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan G, Steele-Perkins V, Morris JF, Rauscher JF, III, Dressler GR: Repression of Pax-2 by WT1 during normal kidney development. Development 1995, 121:867-875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hockenbery D, Nunez G, Milliman C, Schreiber RD, Korsemeyer S: Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature 1990, 348:334-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagata M, Nakauchi H, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, Loh D, Watanabe T: Apoptosis during an early stage of nephogenesis induces renal hypoplasia in bcl-2 deficient mice. Am J Pathol 1996, 148:1601-1611 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Upadhyay S, Li G, Liu H, Chen YQ, Sarker FH, Kim HC: bcl-2 suppresses expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 in breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res 1995, 55:4520-4524 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hewitt SM, Hamada S, Mcdonell TJ, Rauscher FJ, III, Saunders G: Regulation of the proto-oncogenes bcl-2 and c-myc by Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene WT1. Cancer Res 1995, 55:5386-5389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker SB, Eichele G, Zang P, Raws A, Sands AT, Bradley A, Olson EN, Harper JW, Elledge SJ: p53-independent expression of p21 in muscle and other terminally differentiating cells. Science 1995, 267:1024-1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halevy O, Novitch BG, Spicer DB, Skapek SX, Rhee J, Hannon GJ, Beach D, Lasser AB: Correlation of terminal cell cycle arrest of skeletal muscle with induction of p21 by Myo D. Science 1995, 267:1018-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mundel P, Reiser J, Zuniga A, Mejis B, Pavenstadt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W, Zeller R: Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell line. Exp Cell Res 1997, 236:348-358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerdes J, Li L, Schlueter C, Duchrow M, Wohlenberg C, Gerlach C, Stahmer I, Kloth S, Brandt E, Flad HD: Immunobiochemical and molecular biological characterization of the cell proliferation-associated nuclear antigen that is defined by monoclonal antibody Ki-67. Am J Pathol 1991, 138:867-873 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deloia JA, Burlingame JM, Krasnow JS: Differential expression of G1 cyclin during human placentogenesis. Placenta 1997, 18:9-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawamoto H, Koizumi H, Uchikoshi T: Expression of the G2-M checkpoint regulators cyclin B1 and cdc2 in nonmalignant and malignant human breast lesions: immunocytochemical and quantitative image analysis. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:15-23 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramani P, Cowell JK: The expression pattern of Wilms’ tumour gene (WT1) product in normal tissues and paediatric renal tumours. J Pathol 1996, 179:162-168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lloyed RV, Jin L, Quian X, Kulig E: Aberrant p27 expression in endocrine and other tumors. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:401-407 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pezzella F, Tse AGD, Cordell JL, Pufford KAF, Gatter KC, Mason DY: Expression of the bcl-2 oncogene protein is not specific for the 14;18 chromosomal translocation. Am J Pathol 1990, 137:225-232 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]