Abstract

Autosomal dominant hereditary amyloidosis with a unique cutaneous and cardiac presentation and death from heart failure by the sixth or seventh decade was found to be associated with a previously unreported point mutation (thymine to cytosine, nt 1389) in exon 4 of the apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1) gene. The predicted substitution of proline for leucine at amino acid position 90 was confirmed by structural analysis of amyloid protein isolated from cardiac deposits of amyloid. The subunit protein is composed exclusively of NH2-terminal fragments of the variant apoA1 with the longest ending at residue 94 in the wild-type sequence. Amyloid fibrils derived from four previously described apoA1 variants are composed of similar fragments with carboxyl-terminal heterogeneity, but contrary to those variants, which all carry one extra positive charge, the substitution Leu90Pro does not result in any charge modification. It is unlikely, therefore, that amyloid fibril formation is related to change of charge for a specific residue of the precursor protein. This is in agreement with studies on transthyretin amyloidosis in which no unifying factor such as change of charge for amino acid residues has been noted.

Hereditary amyloidosis is a group of late-onset autosomal dominant diseases with amyloid deposition in various tissues. 1 Although a few, such as Alzheimer’s disease 2,3 and medullary carcinoma of the thyroid, 4 give localized disease, most forms of hereditary amyloidosis have systemic distribution. The number of proteins with mutations resulting in amyloidosis has continued to increase. The most frequent form of systemic hereditary amyloidosis is associated with variant forms of transthyretin, but several other proteins are also responsible for diverse clinical forms: gelsolin, fibrinogen Aα-chain, apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1), lysozyme, and cystatin C. 5-10 Clinically, transthyretin amyloidosis most frequently is characterized by peripheral neuropathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, or nephropathy. A unique feature of gelsolin amyloidosis is lattice corneal dystrophy, but cranial neuropathy and some degree of cardiac and renal amyloid deposition is common. Fibrinogen Aα chain amyloidosis is characterized by predominance of renal failure as are apoA1 and lysozyme amyloidosis. Mutations in lysozyme may also give massive hepatic deposition. Cystatin C amyloidosis, although largely limited to intracranial vessels, may give some degree of systemic amyloid deposition.

Mutations in apoA1 are of particular interest because they are associated with a wide clinical spectrum including amyloid neuropathy, nephropathy, or hepatopathy. 11-13 In this paper, we report a novel variant of apoA1 that causes a unique combination of cutaneous amyloid deposition and restrictive cardiomyopathy which leads to death.

Kindred

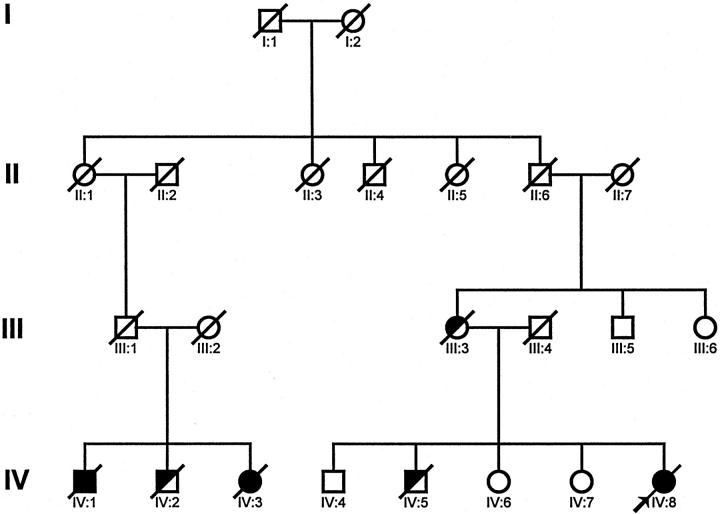

The propositus (IV:8, Figure 1 ▶ ) was a 54-year-old woman who presented in 1991 with recent onset of exertional dyspnea and cutaneous lesions for many years. The skin lesions, which were yellow and maculopapular, first appeared on the forehead and extended rapidly to the face, neck, shoulders, and axillary and antecubital areas. Congo red staining of a skin biopsy demonstrated amyloid deposits in dermal papillae and surrounding blood vessels in the reticular dermis. The amyloid deposits were resistant to treatment with permanganate. Physical examination revealed signs of congestive cardiac failure. The remainder of the clinical examination, including peripheral nervous system, was normal. Chest roentgenogram showed cardiomegaly, and electrocardiogram revealed right bundle branch block. Echocardiography showed concentric thickening of the wall of the left ventricle and a small left ventricular cavity. Cardiac catheterization showed a typical restrictive hemodynamic pattern. Endomyocardial biopsy revealed amyloid deposits. Tests for monoclonal immunoglobulin protein and plasmacytosis were negative. Skin from a typical amyloid-infiltrated area was resected for immunohistochemical studies and was also available for biochemical analysis. Treatment with colchicine was tried but discontinued due to gastrointestinal intolerance. Heart failure progressed, and the patient died in 1997. Heart tissue was frozen for extraction and characterization of the amyloid protein.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of family with cutaneous and cardiac amyloidosis. The propositus (IV:8) is indicated by an arrow. Subjects with histologically proven amyloidosis are indicated by solid symbols. Subjects that died of cardiac disease and are presumed to have been affected are indicated by half-shaded symbols.

A second cousin (IV:3, Figure 1 ▶ ), a 57-year-old woman without notable past medical history, presented in 1982 with a 3-year history of extensive cutaneous maculopapular amyloidosis. 14 Petechial purpura was observed on the skin, the ocular conjunctiva, tonsil pillars, buccal mucosa, and lips. A skin biopsy showed lesions similar to those of her cousin. Chest roentgenogram and electrocardiogram were normal. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis did not detect a monoclonal immunoglobulin. The patient was treated with colchicine (1 mg/day) for 4 years. In 1986, the patient experienced exertional dyspnea and hoarseness. Laryngeal, esophageal, and rectal biopsies all were positive for amyloid. Clinical and electrical neurological examinations continued to be normal. Chest roentgenogram revealed cardiomegaly, and electrocardiogram was consistent with left ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiogram disclosed thickening of the tricuspid and mitral valves and a pericardial effusion. Heart failure was slowly progressive, and the patient died in 1996.

In 1979, the brother of IV:3 (IV:1) presented at age 51 years with similar but much more impressive maculopapular skin lesions than those of his sister. The remainder of the physical examination was normal. A skin biopsy revealed amyloidosis. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis did not detect a monoclonal protein. Liver function tests suggested slight cholestasis:alkaline phosphatase of 133 IU/L (normal, <85 IU/L), total bilirubin of 33 μmol/L (normal, <17 μmol/L). In 1980, exertional dyspnea appeared and worsened progressively to reach stage IV in 1985. An endomyocardial biopsy at that time revealed cardiac amyloidosis. In view of severe cardiac prognosis and lack of other major organ involvement, heart transplantation was performed. Unfortunately, the patient’s outcome was complicated, and he died postoperatively. Autopsy revealed massive amyloid deposits in the heart and adrenals and slight deposits in the liver and spleen.

An older brother of the propositus (IV:5) died at age 41 years of heart disease and, although he may have been affected, no tissues were available for study. Their mother (III:3), an obligate carrier, died at age 62 years with congestive heart failure, but no tissues were studied. Two older sisters of the propositus (IV:6, IV:7) and an older brother (IV:4) are disease free. A brother (IV:2) of the cousins with proven amyloidosis (IV:1 and IV:3) died at age 55 of cardiomyopathy, but no tissues were available for study. The parents of these three siblings died young, the father (III:1) in an accident and the mother (III:2) in childbirth. These three sibs had nine children who are presently younger than the usual age of disease onset. None has been available for study. The propositus had no children.

Materials and Methods

Histology

Sections (6 μm) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded skin and heart were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or with alkaline Congo red by standard techniques. Congo-red-stained sections were viewed by polarized light.

Isolation of Amyloid Fibrils

Amyloid fibrils were isolated from skin and heart of the propositus by a modified procedure of Pras et al. 15 Approximately 2 g of skin was homogenized with 10 ml of 0.1 mol/L sodium citrate, 0.15 mol/L sodium chloride in a tissue homogenizer and centrifuged as previously described. 16 The pellet was homogenized as above three more times, and the final pellet was used for amyloid subunit protein isolation. Approximately 15 g of heart tissue was homogenized with 80 ml of sodium citrate/saline solution in a blender and centrifuged for 30 minutes at 11,000 rpm, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was homogenized as above three more times with sodium citrate/saline solution, eight times with 0.15 mol/L sodium chloride, and four times with water. The final pellet and four water wash supernatants were dialyzed against water and lyophilized. Smears of the heart water washes and of the pellet from both tissues stained with Congo red were positive for amyloid fibrils.

Isolation of Amyloid Subunit Protein

The final wet pellet from skin was suspended in 6 ml of 8 mol/L guanidine hydrochloride, 0.5 mol/L Tris, pH 8.2, containing 1 mg of EDTA/ml, reduced with 10 mg of dithiothreitol/ml for 24 hours at room temperature, and alkylated with 24.1 mg of iodoacetic acid/ml for 30 minutes. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 minutes, the supernatant was chromatographed on a Sepharose CL6B column (2.6 × 90 cm) equilibrated and eluted with 4 mol/L guanidine hydrochloride, 0.05 mol/L Tris, pH 8.2. Eluant was monitored by absorbance at 280 nm. Heart fibrils (140 mg) were suspended in 7 ml of 6 mol/L guanidine hydrochloride, 0.5 mol/L Tris, pH 8.2, containing 1 mg of EDTA/ml, reduced, alkylated, and chromatographed as above. Pooled fractions from both tissues were dialyzed against water, lyophilized, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using the Tricine system of Schägger and Von Jagow. 17

Amino Acid Sequence Analysis

Sepharose CL6B fractionated protein was digested with trypsin (2% w/w) in 0.1 mol/L ammonium bicarbonate at pH 8.0 for 18 hours and then lyophilized. The sample was dissolved in 50% acetic acid and fractionated on a Beckman Ultrasphere-ODS high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (0.46 × 25 cm) eluted with a linear gradient of 0% to 60% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid over 120 minutes. Eluant was monitored by absorbance at 215 nm. Fractions were dried in a Savant Speed Vac concentrator (Savant Instruments, Farmingdale, NY). Samples were sequentially degraded in an Applied Biosystems 473A protein sequencer (Foster City, CA) using standard cycle programs provided by the manufacturer.

DNA Sequence Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from skin by a conventional method. 18

A region of exon 4 of the apoA1 gene 19 containing 214 bp was amplified using E 4-1 primer (5′-TCAACCCTTCTGTCTCACCC-3′) and E 4-2 primer (5′-CTACCTGGACGACTTCCAGAA-3′). PCR conditions were 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 62°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute. PCR products were electrophoresed through 2% Nusieve GTG agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide, and the band was excised and melted in 100 μl of water. Asymmetric PCR for direct DNA sequencing was performed using 1 μl of the gel-purified template and the conditions noted above except for primer ratios of 1:30. Samples were extracted with chloroform and subjected to spin dialysis with a centricon-30 concentrator, and 7 μl of the retentate was used for dideoxynucleotide DNA sequencing by Sequenase version 2.0 as suggested by the manufacturer. Samples were electrophoresed in 8% polyacrylamide gel at 2000 V for 3 hours, dried, and exposed to Kodak XAR film.

RFLP Analysis

Direct nucleotide sequencing of DNA from the propositus showed a thymine to cytosine transition corresponding to the second base of codon 90 of apoA1. This results in the creation of a BamH1 recognition site. To facilitate separation of enzyme-digested PCR product on agarose gel electrophoresis, a new set of primers that produce an 889-bp product were used. The 5′ primer was 5′ TGT ACT GGA AAT GCT AGG CC 3′, and the 3′ primer was 5′ GGA TCT CAA CAA CTC CGT G 3′, corresponding to bp 1134 to 1153 and bp 2004 to 2022 of the genomic apoA1 sequence, respectively. 19 PCR-amplified DNA fragments were digested with the restriction enzyme BamH1 at 37°C for 3 hours, electrophoresed through 3% Nusieve GTG agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV light.

Results

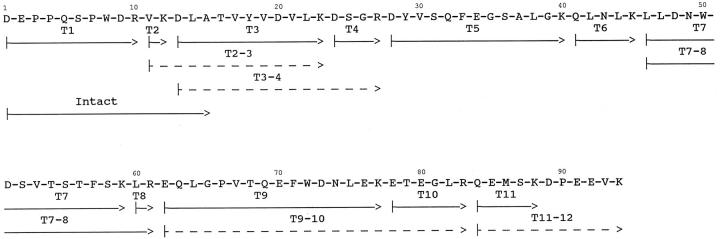

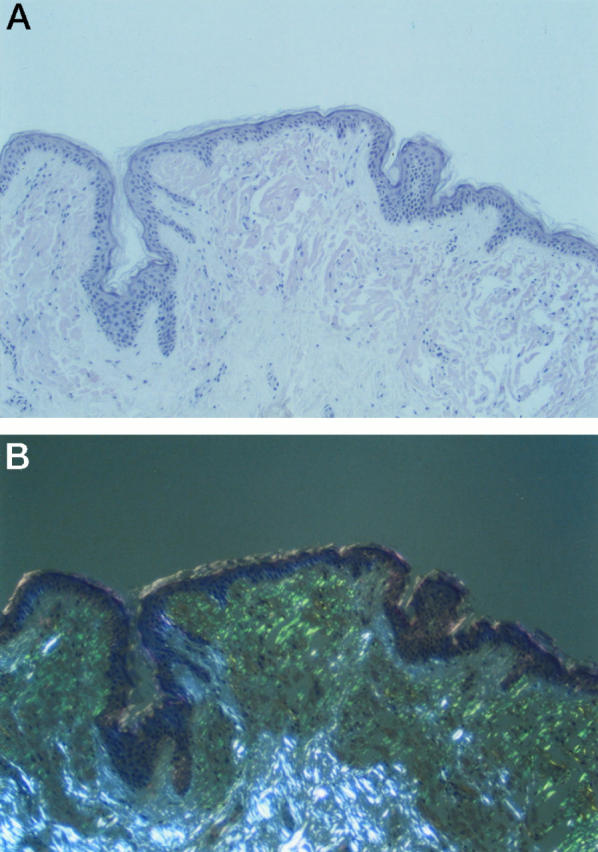

Histological evaluation of skin from the propositus revealed extensive amyloid deposition in subepithelial areas of dermis (Figure 2A) ▶ . Some areas showed a flat epidermis, but considerable papillary formation was present in other areas. Congo-red-stained sections showed typical green birefringence of the amyloid deposits when viewed between crossed polars (Figure 2B) ▶ . Histological sections of postmortem cardiac tissue of a cousin (IV-2) revealed extensive replacement of myocardial fibers with amyloid (Figure 3, A and B) ▶ . Blood vessel walls were also heavily infiltrated with amyloid.

Figure 2.

A: Skin biopsy from proband stained with Congo red. Amyloid deposition forms a band in the upper dermis with papillary formation. B: Viewed with polarized light, amyloid deposits give typical green birefringence, whereas collagen gives white birefringence.

Figure 3.

A: Postmortem cardiac muscle stained with Congo red showing extensive amyloid deposition between muscle fibers and in vessel walls. Marked loss of myocardial fibers is noted. B: Same section viewed by polarized light.

Initially, amyloid fibrils isolated from limited amounts of skin biopsy tissue from the propositus were solubilized with guanidine hydrochloride and fractionated on Sepharose CL6B. Amino acid sequence analysis for 12 cycles of pooled fractions eluting in the 15-kd and lower region yielded a sequence identical to residues 1 to 12 of human apoA1. Analysis of the pooled fractions on SDS-PAGE showed two major bands at approximately 7 and 9 kd. Sequence analysis of both bands after transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane gave an amino-terminal sequence identical to residues 1 to 15 of apoA1, indicating that the difference in molecular weight was most likely due to carboxyl-terminal heterogeneity. Additional sequence characterization of the pool after trypsin digestion and reverse-phase HPLC fractionation identified peptides from residues 1 to 88 of apoA1, all containing the normal apoA1 residues.

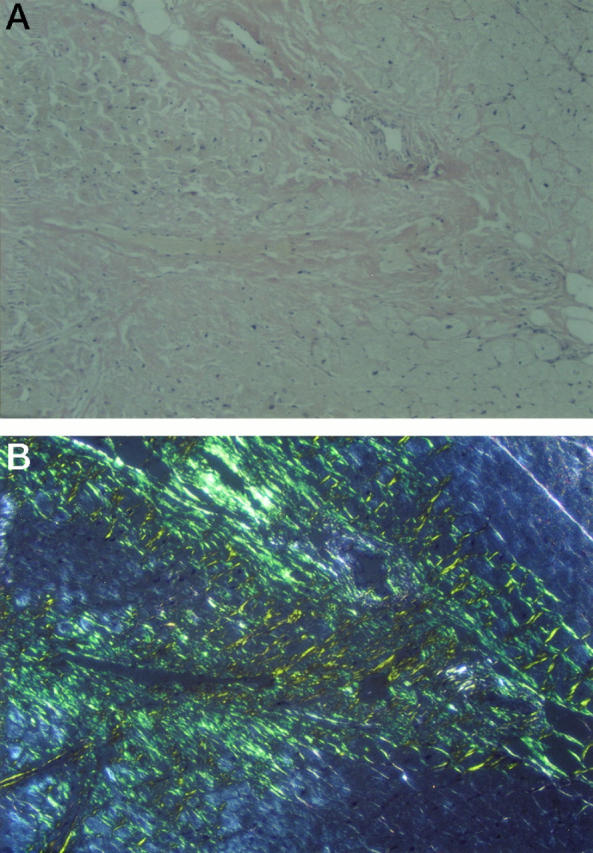

Subsequently, amyloid was isolated from postmortem cardiac tissue from the propositus. After solubilization of fibrils and fractionation on Sepharose CL6B, low molecular weight peak fractions were characterized in the same fashion as for the skin isolated fibrils. Analysis on SDS-PAGE showed two major bands at 7 and 9 kd, similar to the skin amyloid. Both bands, after transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, had an amino-terminal sequence identical to apoA1. The sequence of the entire amyloid subunit protein was determined by analysis of tryptic peptides after reverse-phase HPLC fractionation. Peptides comprising residues 1 to 94 of apoA1 were identified (Figure 4) ▶ . Although T3, T5, T7, and T9 were recovered in similar amounts, the yield of T10 was approximately 75% and T11 approximately 25% that of the others. The yield of T11–12, which contained the Leu90Pro substitution, was only approximately 5% that of the others. These results suggest that the carboxy terminus of the amyloid subunit protein is heterogeneous, in agreement with the SDS-PAGE results, and that the vast majority of the amyloid subunit protein has been proteolyzed to remove the variant Pro90 residue. Whether this occurred before or after fibril formation is unknown.

Figure 4.

Amino acid sequence of the amyloid subunit protein isolated from heart tissue. The arrows indicate the peptides used to determine the amino acid sequence of the amyloid protein. Peptides labeled with T were isolated from HPLC fractionation of a trypsin digest of the subunit protein. The arrow labeled Intact designates the sequence obtained from the undigested sample for 15 cycles. Dashed arrows indicate peptides recovered at ≤10% the molar amount of the other peptides. Amyloid protein isolated from skin deposits gave the same sequence, but no residues beyond position 88 were found.

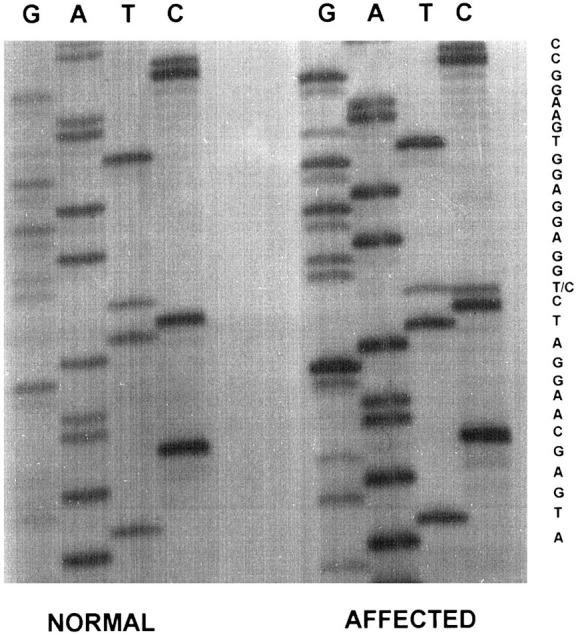

Based on the identification of a fragment of apoA1 in amyloid fibrils isolated from skin, DNA sequencing of the apoA1 gene was performed on genomic DNA isolated from the propositus. PCR amplification of apoA1 exon 4 gave the expected 214-bp product. Direct DNA sequencing detected both thymine and cytosine at the position corresponding to the second base of codon 90 (CTG and CCG), indicating heterozygosity for leucine and proline at this position (Figure 5) ▶ . Direct DNA sequencing of exon 3 of apoA1 revealed only the normal sequence.

Figure 5.

Autoradiograph of DNA sequencing gel of exon 4 of propositus showing heterozygosity at codon 90 with both CTG(Leu) and CCG(Pro).

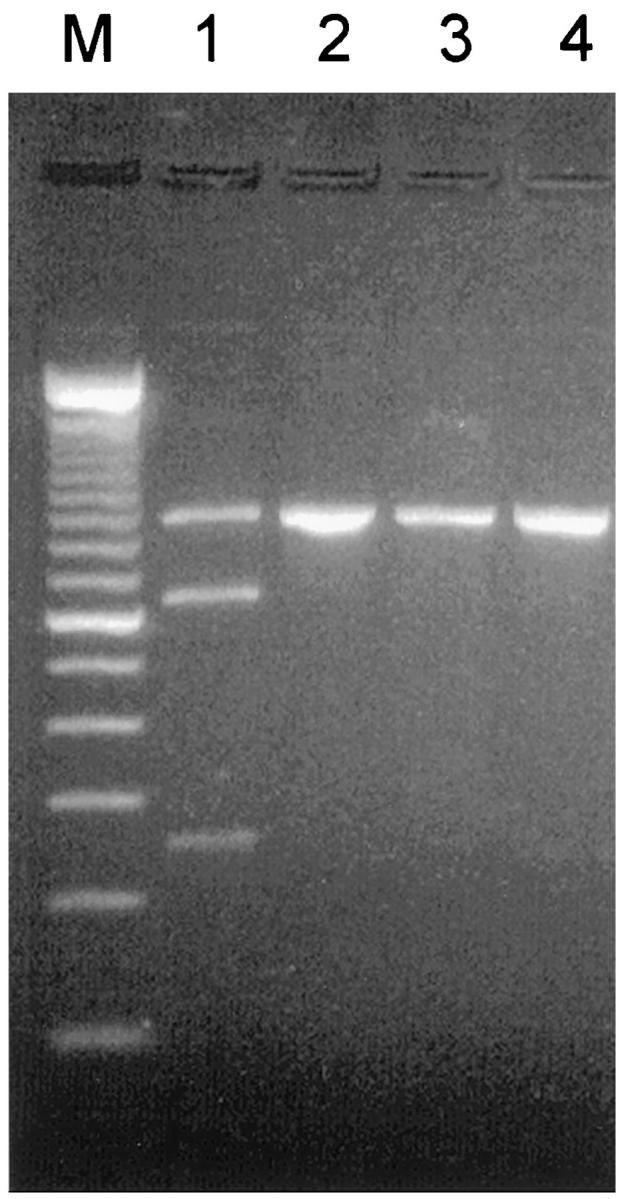

Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the 889-bp PCR product from exon 4 containing the thymine to cytosine transition by digestion with BamH1 gave bands on agarose electrophoresis corresponding to the expected 633- and 256-bp digestion products plus the undigested 889-bp band indicating heterozygosity at this position (Figure 6) ▶ .

Figure 6.

RFLP analysis of exon 4 PCR product of propositus (lanes 1 and 2) and a normal subject (lanes 3 and 4). Lanes 1 and 3, digested with BamH1; lanes 2 and 4, before digestion. Only propositus DNA product (889 bp) shows cleavage to give bands of 633 bp and 256 bp (lane 1).

Discussion

Affected members of the family described here had a unique phenotype of hereditary nonneuropathic systemic amyloidosis with both cutaneous and cardiac disease. The cutaneous amyloidosis is of particular interest because of the extensive deposition in the upper layer of the dermis (Figure 2) ▶ . This deposition would appear to explain the papillary nature of the clinically described dermal lesions. The avascular nature of the amyloid contributes to the yellow appearance of the skin lesions. This is similar to the appearance of dermal amyloid in the immunoglobulin (AL) amyloidosis that may occur on eye lids and occasionally in other areas of skin. As with AL amyloidosis, the dermal deposits of amyloid in this case of apoA1 disease was extensive enough to allow isolation of amyloid fibrils for chemical analysis. 20 This is unlike other forms of familial amyloidosis where deposition is usually limited to adnexal structures, including eccrine glands, apocrine glands, and hair follicles. 21 As is the case with AL amyloidosis, factors governing the predilection of the Leu90Pro apoA1 amyloid to accumulate in the dermis are not apparent. It can be speculated, however, that this feature may be governed by the specific mutation, as none of the previously described apoA1 variants give cutaneous deposits, and in the present kindred, all members with the systemic amyloidosis had skin involvement. 11-13,22-24 In AL amyloidosis the presence of significant cutaneous amyloidosis is sporadic, and if this was governed by any structural factor in the immunoglobulin light chain precursor protein, this factor would be difficult to identify as each AL amyloid light chain precursor is unique.

Other forms of amyloidosis that may give skin deposits include gelsolin, 25 cystatin C, 26 and other, as yet uncharacterized sporadic and hereditary forms. 27-30 These all give limited amounts of amyloid deposition that are useful for diagnosis but are not sufficient for chemical characterization.

The heart is the major organ involved in this kindred and was the cause of death of all three patients studied. Cardiac involvement was described in one patient in a British kindred with the apoA1 Trp50Arg mutation, who was treated with combined heart/liver transplantation for end-stage cardiac and renal failure. 23 However, cardiac involvement has not been reported as a consistent feature in any previously described kindred with apoA1 amyloidosis. Clinical evidence for amyloid cardiomyopathy appeared much later than cutaneous lesions in the patients described here. However, it is not possible to say how long the cardiac amyloid remained occult while the skin disease became visually apparent. It is likely that the cardiac deposition of amyloidosis is a chronic process, as it is in various forms of transthyretin amyloidosis, and is not as rapidly progressive as in AL amyloidosis.

Clinically, the present kindred is distinct from other reported types of hereditary amyloidosis, including transthyretin amyloidosis and amyloidosis associated with other mutations in apoA1. In the Iowa family with the apoA1 Gly26Arg mutation (familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy type III), the disease is characterized by peripheral neuropathy, renal failure, and peptic ulcer disease. 7,11 Other kindreds with the Gly26Arg variant have been reported, and each is distinguished by renal amyloidosis. 12 The same is true of two other forms of apoA1 amyloidosis caused by single amino acid substitutions, Trp50Arg and Leu60Arg, although one individual (noted above) was reported to have cardiomyopathy in addition to renal failure. 22,23 A Spanish kindred was reported with a unique late-onset hepatic amyloidosis leading to death from liver failure in which a deletion/insertion in exon 4 of the apoA1 gene was found. 13 More recently, a second apoA1 deletion mutant has been described in a family with hereditary amyloidosis. 24 None of these families has shown the unique presentation of cutaneous and cardiac amyloidosis.

The mechanisms by which variants of apoA1 form amyloid deposits are unknown. It has recently been discovered that wild-type apoA1 is the precursor protein for pulmonary vascular amyloid in aged dogs 31 and amyloid deposits found in aged human aorta. 32 Thus, apoA1 belongs to the class of proteins, which includes transthyretin and the β-amyloid precursor of Alzheimer disease, that may spontaneously form amyloid in vivo and are associated with aging. 33 In the dominant forms of hereditary amyloidosis it can be hypothesized that mutations in the fibril precursor proteins make them more amyloidogenic. Studies of the crystal structure of transthyretin and lysozyme have supported an essential role of a conformational change induced by mutations, although no unifying factor has been found. 34,35 The tertiary structure of apoA1 has not yet been determined, and changes induced by mutations can only be speculated. It has been proposed that, as the three previously described forms of apoA1 have been associated with point mutations resulting in arginine residues substituted for neutral residues, thus giving one extra charge to the protein, and as the two deletion/insertion mutants also result in a +1 charge, that the change in charge may be important to fibrillogenesis. 24 For those forms of apoA1 that have been studied chemically, the most abundant fragments were from positions 1 to residues 83 to 94, although considerable heterogeneity at the carboxy terminus has been demonstrated by mass spectrometry (1 to 81 to 1 to 113). The variant we report (Leu90Pro) is also situated in the amino-terminal portion of apoA1. However, this is a neutral substitution and does not predict any charge modification of the precursor apoA1 protein. Although this neutral substitution does not preclude a conformational change as has been predicted for many of the transthyretin mutations, it is obvious that a change in charge is not required for the fibrillogenesis process to occur. It would also seem apparent, based on the absence of the mutated residue in the amyloid fibrils of the skin deposits, whereas this residue is present in the cardiac amyloid, that the mutant residue is not structurally required for fibril formation. A similar finding has been noted in the Aβ-peptide of Alzheimer disease where mutations at position 717, which give amyloidosis, are not found within the amyloid plaque protein fibrils. 36 It is possible that the apoA1 mutated residue Leu90Pro, rather than having a direct structural effect at the level of amyloid fibril formation, may be associated with metabolic changes as has been shown with the Alzheimer β-precursor protein 37,38 and with the apoA1 Gly26Arg amyloid precursor. 39 In vitro fibrillogenesis and in vivo metabolic studies of this neutral variant of apoA1 may present new clues on amyloid fibril formation.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Merrill D. Benson, Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, Indiana University School of Medicine, 975 West Walnut Street, IB130, Indianapolis, IN 46202-5251.

Supported by Association Paulette Ghiron-Bistagne contre l’amylose, Association Française contre les Myopathies, a grant for clinical research from Société de Néphrologie, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (1869 for year 1992), R.L.R. Veterans Affairs Medical Research (MRIS 583-0888), grants from the U.S. Public Health Service (AG 10608, DK 42111, DK 49596, and RR-00750), the Marion E. Jacobson Fund, and the Machado Family Research Fund.

References

- 1.Benson MD: Amyloidosis. ed 7 Scriver CR Beaudet AL Sly WS Valle D eds. The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease, 1995, :pp 4159-4191 McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin M-C, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, Giuffra L, Haynes A, Irving N, James R, Mant R, Newton P, Rooke K, Roques P, Talbot C, Pericak-Vance M, Roses A, Williamson R, Rossor M, Owen M, Hardy J: Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 1991, 349:704-706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murrell J, Farlow M, Ghetti B, Benson MD: A mutation in the amyloid precursor protein associated with hereditary Alzheimer’s disease. Science 1991, 254:97-99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sletten K, Westermark P, Natvig JB: Characterization of amyloid fibril proteins from medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. J Exp Med 1976, 143:993-998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson MD, Uemichi T: Transthyretin amyloidosis. Amyloid 1996, 3:44-51 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy E, Haltia M, Fernandez-Madrid I, Koivunen O, Ghiso J, Prelli F, Frangione B: Mutation in gelsolin gene in Finnish hereditary amyloidosis. J Exp Med 1990, 172:1865-1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichols WC, Gregg RE, Brewer HB, Jr, Benson MD: A mutation in apolipoprotein A-I in the Iowa type of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Genomics 1990, 8:318-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson MD, Liepnieks J, Uemichi T, Wheeler G, Correa R: Hereditary renal amyloidosis associated with a mutant fibrinogen α-chain. Nature Genet 1993, 3:252-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pepys MB, Hawkins PN, Booth DR, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Soutar AK, Totty N, Nguyen O, Blake CC, Terry CJ, Feest TG, Zalin AM, Hsuan JJ: Human lysozyme gene mutations cause hereditary systemic amyloidosis. Nature 1993, 362:553-557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghiso J, Pons-Estel B, Frangione B: Hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy: the amyloid fibrils contain a protein which is a variant of cystatin C, an inhibitor of lysosomal cysteine proteases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1986, 136:548-554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Allen M, Frohlich J, Davis J: Inherited predisposition to generalized amyloidosis. Neurology 1969, 19:10-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigushin DM, Gough J, Allan D, Alguacil A, Penner B, Pettigrew NM, Quinonez G, Bernstein K, Booth SE, Booth DR, Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB: Familial nephropathic systemic amyloidosis caused by apolipoprotein AI variant Arg26. Q J Med 1994, 87:149-154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booth DR, Tan SY, Booth SE, Tennent GA, Hutchinson WL, Hsuan JJ, Totty NF, Truong O, Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Bruguera M, Caballeria J, Sole M, Campistol JM, Pepys MB: Hereditary hepatic and systemic amyloidosis caused by a new deletion/insertion mutation in the apolipoprotein AI gene. J Clin Invest 1996, 97:2714-2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moulin G, Cognat T, Delaye J, Ferrier E, Wagschal D: Amylose disséminée primitive familiale (nouvelle forme clinique?). Ann Dermatol Venereal 1988, 115:565-570 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pras M, Schubert M, Zucker-Franklin D, Rimon A, Franklin EC: The characterization of soluble amyloid prepared in water. J Clin Invest 1968, 47:924-933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamidi Asl K, Liepnieks JJ, Bihrle R, Benson MD: Local synthesis of amyloid fibril precursor in AL amyloidosis of the urinary tract. Amyloid 1998, 5:49-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schagger H, Von Jagow G: Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1–100 kDa. Anal Biochem 1987, 166:368-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis J: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, ed 2 1989, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY,

- 19.Seilhamer JJ, Protter AA, Frossard P, Levy-Wilson B: Isolation and DNA sequence of full-length cDNA and of the entire gene for human apolipoprotein AI: discovery of a new genetic polymorphism in the apo AI gene. DNA 1984, 3:309-317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen KE, Sandgren O, Sletten K, Westermark P: Primary localized amyloidosis of the eyelid: two cases of immunoglobulin light chain-derived proteins, subtype lambda V respectively lambda VI. Clin Exp Immunol 1996, 106:362-366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubinow A, Cohen AS: Skin involvement in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Neurology 1981, 31:1341-1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soutar KA, Hawkins PN, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Booth SE, Hutton T, Nguyen O, Totty NF, Feest TG, Hsuan JJ, Pepys MB: Apolipoprotein AI mutation Arg60 causes autosomal dominant amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992, 89:7389-7393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booth DR, Tan SY, Booth SE, Hsuan JJ, Totty NF, Nguyen O, Hutton T, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Hutchinson WL, Thomson N, Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB: A new apolipoprotein AI variant, Trp 50 Arg, causes hereditary amyloidosis. Q J Med 1995, 88:695-702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persey MR, Booth DR, Booth SE, Van Zyl-Smit R, Adams BK, Fattaar AB, Tennent GA, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB: Hereditary nephropathic systemic amyloidosis caused by a novel variant apolipoprotein A-I. Kidney Int 1998, 53:276-281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorevic PD, Munoz PC, Gorgone G: Amyloidosis due to a mutation of the gelsolin gene in an American family with lattice corneal dystrophy type II. N Engl J Med 1991, 325:1780-1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benedikz E, Blšndal H, Gudmundsson G: Skin deposits in hereditary cystatin C amyloidosis. Virchows Arch A (Pathol Anat) 1990, 417:325-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang WJ: Clinical features of cutaneous amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol 1990, 8:13-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasily DB, Bhatia SG, Uhlin SR: Familial primary cutaneous amyloidosis. clinical, genetic, and immunofluorescent studies. Arch Dermatol 1978, 114:1173-1176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton JA, Jagjvan A, Bhogal B, McKee PH, McGibbon DH: Familial primary cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol 1985, 112:201-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajagopalan K, Tay CH: Familial lichen amyloidosis: report of 19 cases in 4 generations of a chinese family in Malaysia. Br J Dermatol 1972, 87:123-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson KH, Sletten K, Hayden DW, O’Brien TD, Roertgen KE, Westermark P: Pulmonary vascular amyloidosis in aged dogs: a new form of spontaneously occurring amyloidosis derived from apolipoprotein A1. Am J Pathol 1992, 141:1013-1019 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westermark P, Mucchiano G, Marthin T, Johnson KH, Sletten K: Apolipoprotein AI-derived amyloid in human aortic atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol 1995, 147:1186-1192 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westermark P, Sletten K, Johansson B, Cornwell GG: Fibril in senile systemic amyloidosis is derived from normal transthyretin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87:2843-2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton JA, Steinrauf LK, Braden BC, Liepnieks J, Benson MD, Holmgren G, Sandgren O, Steen L: The x-ray crystal structure refinements of normal human transthyretin and the amyloidogenic Val-30→Met variant to 1.7-Å resolution. J Biol Chem 1993, 268:2416-2424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Booth DR, Sunde M, Bellotti V, Robinson CV, Hutchinson WL, Fraser PE, Hawkins PN, Dobson CM, Radford SE, Blake CCF, Pepys MB: Instability, unfolding and aggregation of human lysozyme variants underlying amyloid fibrillogenesis. Nature 1997, 385:787-793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liepnieks JJ, Ghetti B, Farlow M, Roses AD, Benson MD: Characterization of amyloid fibril-peptide in familial Alzheimer disease with APP 717 mutations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993, 197:386-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung AY, Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lieberburg I, Selkoe DJ: Mutation of the β-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer’s disease increases β-protein production. Nature 1992, 360:672-674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomita T, Maruyama K, Saido TC, Kume H, Shinozaki K, Tokuhiro S, Capell A, Walter J, Grünberg J, Haass C, Iwatsubo T, Obata K: The presenilin 2 mutation (N141I) linked to familial Alzheimer disease (Volga German families) increases the secretion of amyloid β protein ending at the 42nd (or 43rd) residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:2025-2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rader DJ, Gregg RE, Meng MS, Schaefer JR, Zech LA, Benson MD, Brewer HB, Jr: In vivo metabolism of a mutant apolipoprotein, ApoA-IIOWA, associated with hypoalphalipoproteinemia and hereditary systemic amyloidosis. J Lipid Res 1992, 33:755-763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]