Abstract

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy is a major cause of morbidity and mortality of cardiac transplant recipients. The underlying cause of this disease remains unclear. Histological studies have implicated accelerated hemostasis and intravascular fibrin deposition in its pathogenesis. In the present study a defined model of this disease in the rat was used to elucidate the implication of tissue factor in the production of the hypercoagulable state observed in cardiac allograft vessels. Tissue factor protein and mRNA expression were studied in rat heart allografts developing allograft vasculopathy resembling human disease. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated tissue-factor-positive cells present in the allograft coronary intima and adventitia. Significant staining for tissue factor was detected in the endothelium lining coronary lesions in cardiac allografts and in interstitial mononuclear cells, respectively. Both transplant coronary endothelial cells and mononuclear cells contained tissue factor mRNA as indicated by oligo-cell reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction after laser-assisted cell picking. In contrast, tissue factor mRNA and protein were not or negligibly dectectable within the coronary intima of nontransplanted control hearts. Thus, the present study clearly demonstrates that aberrant tissue factor expression occurs within the coronary intima after cardiac transplantation. Tissue factor, activating downstream coagulation mechanisms, may account for the intravascular clotting abnormalities observed in cardiac allografts and may represent a key factor in transplant atherogenesis.

The development of an unusually accelerated form of coronary artery disease, termed cardiac allograft vasculopathy, has become the major cause of long-term morbidity and mortality in the increasing number of heart transplant survivors. 1 With no real solution to understanding its pathogenesis or to preventing its development, cardiac graft vasculopathy is the predominant cause of graft loss and retransplantation after the first year after transplantation and one of the most discouraging aspects of heart transplantation today. 2

The pathology of cardiac allograft vasculopathy is characterized by an obliterative myointimal proliferation that affects the whole length of the coronary arteries, including epicardial arteries and small penetrating intramyocardial branches. However, the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for the development of transplant vasculopathy are incompletely understood. Although it has been postulated that this panvasculitis may emerge in response to alloreactive immune-mediated damage of the vessel intima, the role of immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis remains highly speculative. 3 In fact, despite the better control of immune responses and fewer acute rejection episodes with the introduction of current immunosuppressive therapy, there has been no concomitant reduction in the development of transplant vasculopathy. 3,4 Thus, with regard to the presence of an intact endothelial monolayer seen on vascular lesions of this disease, 5 the absence of a true vasculitic picture 6-8 and the lack of standard atherogenic risk factors, 9,10 respectively, transplant-induced vasculopathy may occur by mechanisms different from that of conventional atherosclerotic events or classic cell-mediated/humoral allograft rejection. Histological examinations characterizing early pathological changes in the coronary artery of allografted hearts suggest that intravascular activation of the coagulation system might be closely involved in the pathogenesis of the disease and that the clotting abnormalities observed within the coronary system of cardiac allografts may have a more significant role in the induction of cardiac graft vasculopathy than was hitherto considered. 11,12 Intraluminal and intralesional thrombus formation as well as fibrin deposition along the vessel intima commonly observed in coronary arteries after cardiac transplantation 13 may be directly involved in the initiation and progression of transplant vasculopathy by stimulating migration of smooth muscle cells from the inner media to intima and proliferation in the intima. 14-16

Given its role as the primary initiator of the coagulation protease cascade, tissue factor (TF), an integral 47-kd cell membrane-bound glycoprotein, may contribute to the intravascular thrombus and fibrin formation observed in cardiac allografts. 17 TF, normally absent in circulating blood cells and endothelium and functionally sequestered from circulating blood by predominant expression in the vascular adventitia, 18,19 is inducible expressed in a number of cell types, including endothelial cells, 20-22 monocytes, 23-25 fibroblasts, 26 and vascular smooth muscle cells 27 in response to a variety of inflammatory and immunological stimuli. It is tempting to speculate that the development of intimal hyperplasia after cardiac transplantation involves the induction of TF in the intima or media of the affected vessels. The purpose of the present study therefore was to determine the presence of TF expression in the vessel wall of cardiac allografts. The distribution, extent, and cellular localization of TF expression in allograft vasculopathy lesions was assessed in a rat heterotopic heart transplantation model.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult, inbred male Lewis (RT1) and F-344 (RT1) rats weighing 250 to 300 g were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY). All rats were housed under conventional conditions and maintained on standard laboratory rat chow and water ad libitum.

Heterotopic Heart Transplantation

Lewis rats served as donors and F-344 rats as recipients. Heterotopic heart transplantation was performed using a cuff anastomosis technique as described previously. 28 The recipients were anesthetized with phentanylcitrate, 0.315 mg/kg body weight, given intramuscularly. The abdomen was opened with a midline incision, the left kidney was removed, and the kidney vessels were cuffed as described elsewhere. 28 The donors were anesthetized with pentobarbital, 60 mg/kg body weight intraperitoneally, and 300 IU of heparin was injected intravenously before harvesting the heart. The grafts were flushed with cold Ringer lactate solution containing 50 IU of heparin/ml. Immediately after harvesting, the graft was anastomosed with the cuffed vessels; the cold ischemic times did not exceed 10 minutes. Cardiac allograft survival was monitored by daily palpation of the graft. Allografts were followed for 120 days after transplantation. The recipients were treated with daily intraperitoneal cyclosporine A (Sandoz, Basel, Switzerland) beginning on the day of transplantation. The initial dose of 2 mg/kg body weight/day was reduced to 0.5 mg/kg body weight/day on postoperative day 80.

Histological Examination

All hearts continued to beat throughout the study period. Rats were killed after 120 days by deep phenobarbital anesthesia. The heart allografts, the recipients’ own hearts, and other pertinent tissues were removed. Native nontransplanted donor hearts served as controls. Hearts were promptly sectioned into five slices: 1) basal (included the atria and the base of the ventricles), 2 to 4) middle (included the midportion of the ventricles), and 5) apical (included the ventricular apex). Slices 1, 2, 4, and 5 were embedded in isopentane-precooled OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN), quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for future processing. Frozen sections were cut at 5 μm, fixed in acetone, and immunostained using the alkaline phosphatase and anti-alkaline-phosphatase (APAAP) method. 29 Slice 3 was fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde solution for 24 hours and embedded in paraffin. The sections were routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and elastic van Gieson for regular histopathological analysis. The sections were examined by standard light microscopy and scored for both the severity of rejection and cardiac allograft vasculopathy (Tables 1 and 2 ▶ ▶ ; Figure 1 ▶ ), using previously described scoring systems. 30,31 Large vessels were defined as arteries with more than two smooth muscle cell layers; small vessels were defined as arteries/arterioles with two or fewer smooth muscle cell layers.

Table 1.

Histological Grading Scale for the Assessment of Degree of Rejection

| Grade | Histological appearance |

|---|---|

| 0 | No rejection |

| 1 | Mild rejection with scanty mononuclear cell infiltrate; minimal or no fibrosis |

| 2 | Moderate rejection with moderate mononuclear cell infiltrate |

| 3 | Severe rejection with diffuse and severe mononuclear cell infiltrate, focal hemorrhage, and necrosis |

Table 2.

Histological Grading Scale for the Assessment of Degree of Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy

| Grade | Histological appearance |

|---|---|

| 0 | Vessel unaffected |

| 1 | Accumulation of inflammatory cells along intimal surfaces but with <10% occlusion of the lumen |

| 2 | More advanced lesion including definite intimal proliferation and thickening with <50% of the lumen |

| 3 | High-grade occlusion of the vessel with >50% of its lumen |

| 4 | 100% vessel occlusion of lumen |

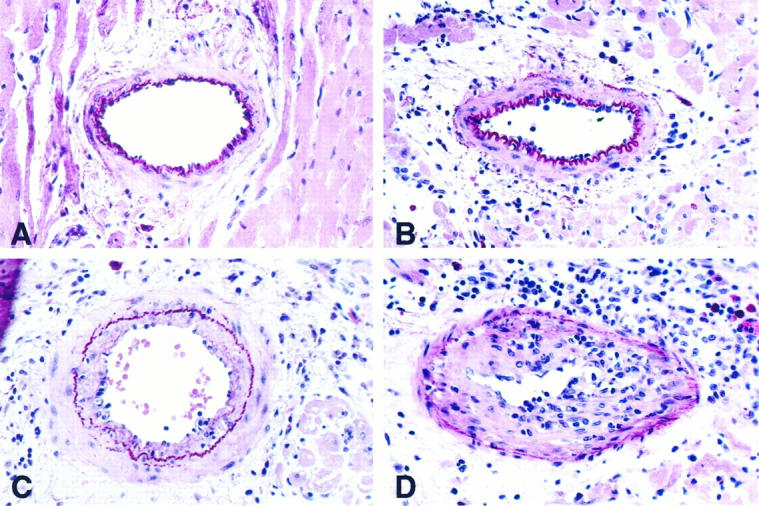

Figure 1.

Sections of rat cardiac allografts illustrating various features and degrees of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. A: Normal small intramyocardial artery (grade 0) with intact internal elastic lamina and single-cell layer endothelium. B: Minimal allograft vasculopathy (grade 1) with patchy endothelial protrusions, endothelial swelling, and adherence of a few inflammatory cells. C: Moderate allograft vasculopathy (grade 2) with concentric intimal proliferations and less than 50% obliteration of the lumen. D: Severe allograft vasculopathy (grade 3) with high-grade intimal proliferations and inflammatory cell infiltrate. H&E/elastic-van Gieson stain; original magnification, ×20 (A to C) and ×40 (D); .

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed by the highly sensitive alkaline phosphatase (APAAP) technique, using a slightly modified method of Cordell. 29 Briefly, freshly prepared, acetone-fixed cryostat sections (5 μm) were incubated for 30 minutes with primary antibodies at room temperature, followed by a 30-minute incubation at room temperature with rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobuline (rabbit “link”, 1:40; Dako, Hamburg, Germany) supplemented with pooled rat serum (1:750; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) to inhibit nonspecific cross-reactivity, and APAAP complex (1:50; Dako), respectively. The “link” and APAAP steps were repeated for 10 minutes. The samples were thoroughly washed in Tris/HCL-buffered saline (pH 7.6) between the “link” and APAAP steps. Alkaline phosphate substrate reaction with new fuchsin (100 μg/ml) and levamisole (400 μg/ml) was performed for 30 minutes at room temperature. Immunohistology for TF antigen was performed using the murine monoclonal rabbit TF antibody AP-1 (0.375 μg/ml, kindly provided by Dr. Michael D. Ezekowitz, Yale University New Haven, CT), the production, purification, and characterization of which are reported elsewhere. 32 The ability of the antibody to cross-react with rat TF apoprotein was assessed by immunoblotting with rat brain thromboplastin. Two hundred micrograms of rat brain acetone salt (Sigma) was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% gel), transferred to nitrocellulose, and incubated with the mouse anti-rabbit TF antibody (0.375 μg/ml) for 1.5 hours at room temperature after blocking with 5% milk protein for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse secondary antibody (0.3 μg/ml; Amersham, Freiburg, Germany) was added. Final bands were detected on x-ray film using the enhanced chemiluminescent system (Amersham). As a positive control for TF, immunohistochemistry was performed on sections of rat kidney. To confirm the identity of cells positive for TF staining, murine monoclonal antibody to rat monocytes/macrophages (clone ED1, 0.22 μg/ml; Camon, Wiesbaden, Germany) and to rat endothelial cell antigen-1/pan-endothelium (clone HIS 52, 1:100; Camon) were used. Negative controls were performed using mouse anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (clone MR 12/53, 0.425 μg/ml; Dako). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted in gelatin.

Laser-Assisted Cell Picking and Tissue Factor RT-PCR

Cryosections (5 μm) of transplanted (n = 10) and nontransplanted control hearts (n = 5) were prepared. Three sections of each heart were collected into a microcentrifuge tube and stored at −80°C. Afterwards, tissue was homogenized (Fisher Scientific, Nidderau, Germany) using the RNAzol-B (WAK, Bad Homburg, Germany) method for RNA extraction. For cell picking, three sections of each heart were mounted on glass slides (thickness, 0.17 mm) and stored at −20°C for several hours until further investigation. In both preparations, Kwok’s criteria for avoidance of contamination were meticulously obeyed. 33 Histological sections were stained with hemalaun (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) according to standard procedures, subsequently immersed in 70%, 96%, and 100% ethanol, and stored up to 2 hours in 100% ethanol until cell picking.

Laser-Assisted Cell Picking and Cell Lysis

Oligo-cell samples of endothelial cells and monocytes/macrophages (five to seven cells), respectively, of intramyocardial arteries from transplanted and control hearts were collected by cell picking. In brief, a sterile syringe needle (30 gauge, 1/2 inch) on a micromanipulator, a computer-controlled microscope stage, and an ultraviolet (UV)-laser microbeam (P.A.L.M., Wolfratshausen, Germany) connected with an inverse microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 135, Zeiss, Jena, Germany), a CCD camera, and a frame grabber were used as described elsewhere 34 (depicted in Figure 4 ▶ ). The highly precise UV-laser system is able to produce gaps of 1 μm in histological sections, 35 allowing the separation of a single endothelial cell layer from the adjacent media. At ×400 magnification, media cells and adventitia cells were photolysed by UV-laser pulses. From normal intima, endothelia were picked in microclusters of two cells, and from intimal proliferations, clusters of three to five cells were picked and transferred into a precooled 0.5-ml reaction tube, containing 10 μl of freshly prepared FSB buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mmol/L KCl, 3 mmol/L MgCl2, 4% RNAse inhibitor (20 U/μl; Perkin Elmer, Weiterstadt, Germany), and 0.5% Igepal CA-630 (Sigma)). 36 After incubation on ice for 5 minutes, samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

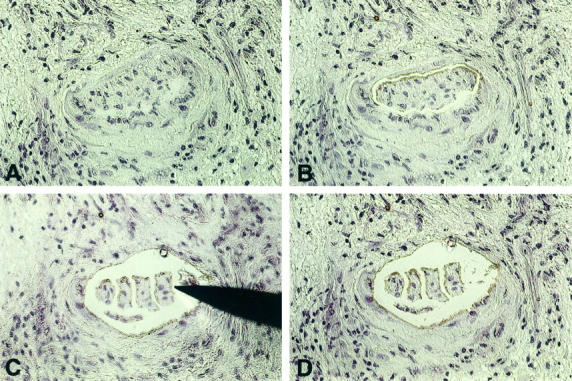

Figure 4.

Demonstration of laser-assisted cell picking in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. A: Advanced occlusion of an intramyocardial coronary artery (hemalaun-stained frozen section). B: Intimal proliferations were dissected free from media by UV-laser microbeam. C: Subdivision of intimal proliferations into oligo-cellular clusters and picking of a cluster with a syringe needle. The picked cell cluster is adhesive to the needle and is lifted under microscopic control. D: Section after removal of the intima cell cluster. Now the next cluster can be picked. Original magnification, ×20.

cDNA Synthesis and RT-PCR

Samples were incubated for 10 minutes at 70°C for RNA denaturing and then rapidly cooled on ice. For cDNA synthesis, 1 μl of random hexamers (50 μmol/L; Perkin Elmer), 0.5 μl of RNAse inhibitor (20 U/μl; Perkin Elmer), 1 μl of dNTPs (10 mmol/L each; Eurobio, Raunheim, Germany), 50 U of MuLV reverse transcriptase (Perkin Elmer), and 4 μl of H2O were added. First-strand reactions, 10 minutes at 20°C, 60 minutes at 43°C, and 5 minutes at 99°C, were performed using a TRIO Thermoblock (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany). cDNA was stored at −20°C until used for PCR. One-half of cDNA was used for porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD) housekeeping gene detection (L. Fink, U. Stahl, L. Ermert, W. Kummer, W. Seeger, and R.M. Bohle, manuscript submitted). The second half was used for TF PCR together with 10 pmol of reverse (5′-TCCAAGTTAAATTAAACGCTTTCCC-3′) and forward (5′-CCACCTTTCTC-GGCTTCCTT-3′) primer sequence (accession number U07619), 1 μl of dNTPs (10 mmol/L each; Eurobio), and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin Elmer) in a total volume of 50 μl. Reaction buffer (Perkin Elmer) contained 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2. PCR conditions (TRIO Thermoblock, Biometra) for cell-picking templates were 94°C for 2 minutes 45 seconds; 60 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, 62°C for 45 seconds, and 73°C for 45 seconds; and 73°C for 5 minutes. PCR conditions for complete heart slices were 94°C for 2 minutes 45 seconds; 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, 62°C for 45 seconds, and 73°C for 45 seconds; and 73°C for 5 minutes. Fifteen percent of each PCR reaction was electrophoresed together with a φ X 174 HinfI size marker on a 2.5% agarose/Tris-buffered ethanolamine gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

Statistical Analysis

Significance of differences between transplanted and nontransplanted hearts was determined by the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

Results

Histopathological Observations

At the time of sacrifice (day 120 after transplantation) all of the cardiac allografts were beating. The histological score evaluating the degree of cellular interstitial rejection at the time of sacrifice was 1.5 ± 0.53 (median, 1.5). Allografts exhibited mild to moderate myocardial rejection with focal areas of mononuclear cell infiltration, cardiomyocytolysis, and some degree of endomyocardial fibrosis and interstitial fibrosis. The nontransplanted native donor hearts generally demonstrated an entirely normal morphological structure with no signs of vascular obliteration or endocardial/myocardial damage.

A total of 646 artery cross sections in 15 rats (10 transplanted and 5 nontransplanted) were available for the study. We found that up to 90% (89.7 ± 10.3) of vessels were affected by transplant vasculopathy in all allografts removed at day 120 after transplantation (average lesion grade, 2.9), thereby confirming previous studies performed in the same donor-recipient graft model. 37 The nontransplanted native hearts had morphologically normal coronary arteries.

Rat cardiac allografts developed coronary vascular lesions indistinguishable in appearance from human accelerated graft vasculopathy (shown in Figure 1 ▶ ). Whereas early lesions with less than 10% occlusion demonstrated patchy endothelial protrusions, endothelial swelling and adherence of a few mononuclear cells along the vessel intima (Figure 1B) ▶ , advanced lesions with more than 50% occlusion were characterized by a marked cellular expansion of the intima and an inflammatory infiltrate typically found within the internal elastica lamina and in a halo zone exterior to the adventitia (Figure 1D) ▶ . Occasionally, the internal elastic membrane was stretched and focally disrupted in advanced lesions. Diffuse fibrointimal thickening that markedly compromised the lumen resulted in a virtually complete occlusion of some coronary arteries.

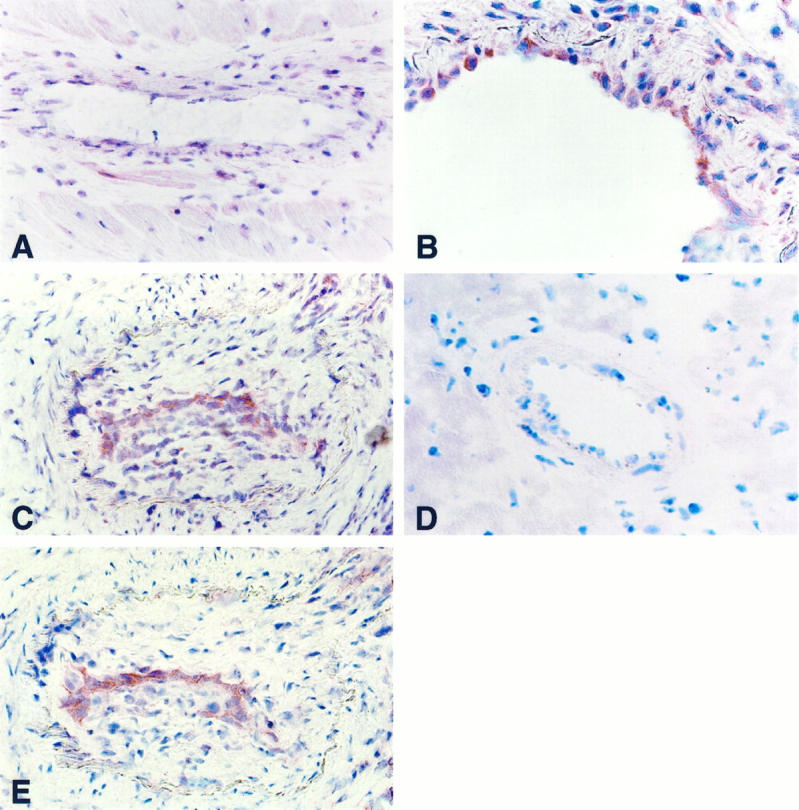

TF Antigen Detection in Coronary Vessels of Nontransplanted Hearts

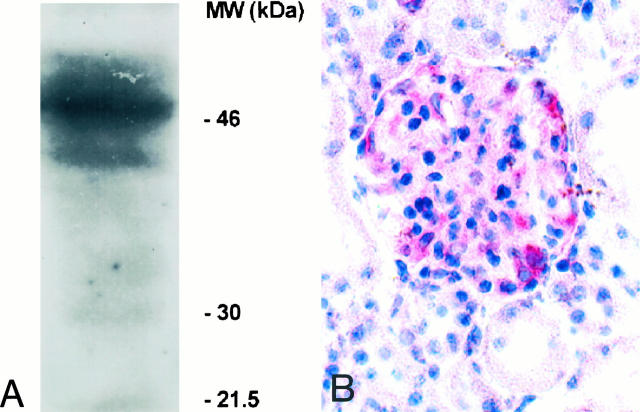

TF antigen detection in cryosections of transplanted and nontransplanted hearts was performed using the anti-rabbit TF monoclonal antibody AP-1. The ability of AP-1 to cross-react with rat TF was established by detection of the 47,000 molecular weight band of reduced TF by immunoblotting with rat brain acetone salt (Figure 2A) ▶ . As a positive control for TF, immunostaining was performed on sections of rat kidney, demonstrating TF-specific staining of the kidney glomeruli when AP-1 was used for immunohistochemistry (Figure 2B) ▶ . There was no or negligible TF detectable in the coronary system of nontransplanted control hearts by immunohistochemistry (Figure 3A) ▶ . In some rare intramyocardial nontransplant vessels, focal areas of vascular endothelium stained weakly for TF (2.1% of sections analyzed).

Figure 2.

Recognition of rat tissue factor by AP-1. A: The ability of the mouse anti-rabbit TF antibody AP-1 to cross-react with rat TF was established by Western blot analysis. AP-1 recognizes the 47-kd band of TF in rat brain acetone salt (source of TF). B: As a positive control for TF, immunohistochemical staining was performed on sections of rat kidney, demonstrating anti-TF staining of a rat kidney glomerulus. Original magnification, ×40.

Figure 3.

Detection and localization of TF in coronary lesions of rat cardiac allograft vasculopathy by APAAP immunohistochemistry. A: Section of an intramyocardial artery from a nontransplanted control heart without anti-TF staining. B: Cardiac allograft, with enhanced TF antigen expression in intimal cells in mild cardiac allograft vasculopathy. C and E: Severe cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Serial sections show enhanced TF expression at the luminal border of intimal proliferations (C) corresponding to luminal endothelial cells stained with the anti-rat pan-endothelium (E). D: No immunostaining is seen using the mouse anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (negative control). Original magnification, ×20 (A, C, and E) and ×40 (B and D).

TF Antigen Detection in Coronary Vessels of Transplanted Hearts

All 10 transplanted hearts showed positive vascular TF staining in approximately one-half of the tissue sections analyzed (46% of sections analyzed; Table 3 ▶ ). Intense TF antigen labeling was detected predominantly in the coronary intima with moderate labeling of the adventitia. No or only faintly focal staining of the media was observed. By co-localization of a rat pan-endothelial antigen in serial sections, intimal TF-positive cells were identified as endothelial cells lining the vascular lumen. Representative photographs of transplant coronary artery sections after immunostaining with antibodies to TF and pan-endothelial antigen are shown (Figure 3) ▶ . Moderate staining for TF was also seen in cells of the monocyte/macrophage origin infiltrating the intima, media, adventitia, or the interstitium of transplanted hearts. Extracellular staining for TF was only rarely detected and most often observed in tissue areas with mononuclear cell infiltrates. TF protein expression on coronary endothelial cells was found in all stages of transplant vasculopathy but was most frequently detected within less severe arterial lesions. TF expression was seen in both large and small coronary vessels and did not depend on the rejection grade at the time of sacrifice. No immunostaining was seen using mouse anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Figure 3D ▶ ; negative control).

Table 3.

Expression of TF in Normal (Nontransplanted) and Transplant Coronary Arteries

| Molecular expression | Normal arteries | Transplant arteries | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Location | Frequency | Location | |

| TF protein | 3/157 (2%) | EC | 87/187 (46%) | EC, M |

| TF mRNA | 2/9 (22%) | EC | 9/11 (82%) | EC |

| 0/7 (0%) | 8/9 (89%) | M |

Frequency is given for percentage of sections (TF protein) and percentage of specimens (TF mRNA) analyzed. EC, endothelial cell; M, monocyte/macrophage.

Presence of TF mRNA in the Coronary Intima in Transplanted and Nontransplanted Hearts

Coronary intimal cells as well as cells of the monocyte/macrophage origin in transplanted and nontransplanted hearts were examined for TF mRNA by use of laser-assisted cell picking, a novel technique for analysis of single- and oligo-cell preparations (illustrated in Figure 4 ▶ ).

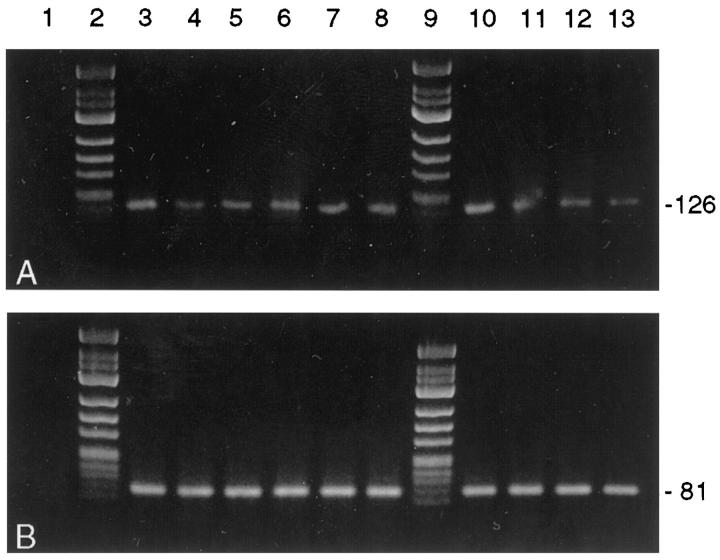

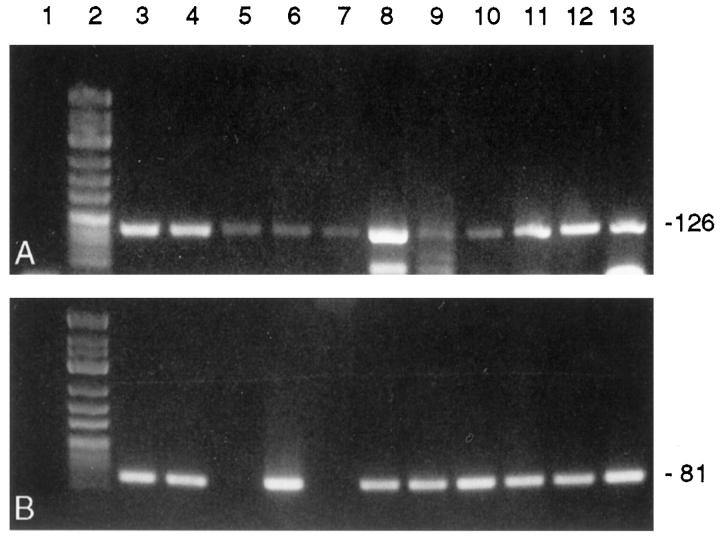

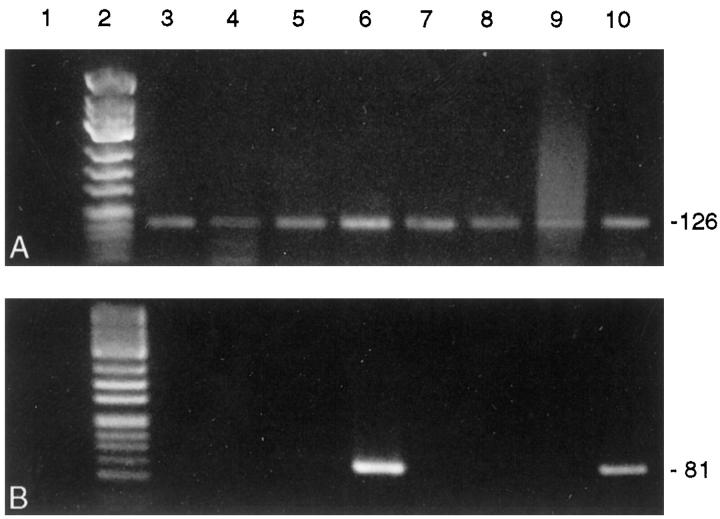

PBGD housekeeping gene mRNA was detected in 10/10 cDNA preparations of complete heart slices of the transplanted and nontransplanted control hearts (Figure 5A) ▶ , and 28/31 (90%) samples prepared by cell picking (each containing cDNA equivalents of five to seven endothelial cells or cells of the monocyte/macrophage system, respectively) were PBGD positive. When analyzing complete slices from either transplanted hearts or nontransplanted native hearts, no differences in TF mRNA expression could be detected. Amplifiable TF mRNA was present in six of six cDNA preparations from complete transplant heart slices and in four of four DNA preparations from complete control hearts (Figure 5B) ▶ . However, laser-assisted cell picking of endothelial cells from transplanted hearts detected TF mRNA transcripts in 9/11 (82%) oligo-cell samples (Figure 6B) ▶ whereas TF transcripts could be detected in only 2/9 (22%) intima samples of nontransplanted control hearts (P = 0.023; Figure 7B ▶ ). Eight of nine (89%) RNA preparations from interstitial monocytes/macrophages of transplanted hearts contained amplifiable TF mRNA. Data of TF mRNA and protein expression in normal and transplant coronary arteries are summarized in Table 3 ▶ .

Figure 5.

Detection of PBGD mRNA (A) and TF mRNA (B) in complete heart slices after tissue homogenization by RT-PCR. Lane 1, negative controls; lanes 2 and 9, molecular weight marker φ X 174 HinfI; lanes 3 to 8, transplant heart slices (n = 6 rats); lanes 10 to 13, control heart slices (n = 4 nontransplanted rats). TF mRNA was detected in transplant and nontransplant heart slices. Amplicon sizes (in bp) are indicated on the right. The 3% agarose/TBE gel was stained with ethidium bromide.

Figure 6.

Detection of PBGD mRNA (A) and TF mRNA (B) in oligo-cellular intimal preparations isolated from transplant hearts by laser-assisted cell picking and subsequent RT-PCR. Lane 1, negative controls; lane 2, molecular weight marker φ X 174 HinfI; lanes 3 to 13, intimal cell preparations from 11 intramyocardial arteries showing transplant vasculopathy (n = 8 rats). TF mRNA was detected in 9/11 cell clusters. Amplicon sizes (in bp) are indicated on the right. The 3% agarose/TBE gel was stained with ethidium bromide.

Figure 7.

Detection of PBGD mRNA (A) and TF mRNA (B) in oligo-cellular intimal preparations isolated from nontransplanted control hearts by laser-assisted cell picking and subsequent RT-PCR. Lane 1, negative controls; lane 2 , molecular weight marker φ X 174 HinfI; lanes 3 to 10, intimal cell preparations from 8 normal intramyocardial arteries (n = 4 rats). TF mRNA was detected in 2/8 cell clusters. Amplicon sizes (in bp) are indicated on the right. The 3% agarose/TBE gel was stained with ethidium bromide.

Discussion

Considerable histological evidence links the activation of blood coagulation with the pathogenesis of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. The source of the intravascular hypercoagulability has not been previously determined. To our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate the presence of TF in vascular lesions of transplant vasculopathy.

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy is manifested by a rapidly developing and rapidly progressing obliterative vascular disease affecting all segments of both epicardial and intramural coronary arteries and veins. 38 The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms still remain unclear. Sequential histological studies demonstrating fibrin deposition along the vessel intima and intraluminal thrombus formation have suggested that intravascular activation of the blood coagulation plays a pivotal role in the development of transplant vasculopathy. 11,13,39 The biochemical source for this intravascular activation, however, is largely unknown.

We hypothesized that TF, a membrane-bound glycoprotein that functions as a key protein in the activation of the clotting system by catalyzing both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of the blood coagulation, 17,40 might be associated with the hypercoagulable state observed in coronary transplant vessels. As major procoagulant, TF is normally absent from circulating blood. Under certain circumstances, however, TF is known to be inducibly expressed by various vascular cells and to promote intravasal coagulation. Indeed, aberrant TF expression within the vascular bed has been associated with the intravasal clotting activation observed in a variety of inflammatory and immunological diseases. 41-43 This study demonstrating expression of TF within the intima of coronary arteries after cardiac transplantation suggests that TF may participate in the thrombogenicity of transplant coronary arteries.

The primary finding of the present study is that TF expression is increased in the coronary intima in allografted hearts, suggesting that TF activation in coronary arteries occurs as a result of heart transplantation. TF-reactive cells predominantly were identified in the intima and the adventitia of graft coronary arteries. Intimal TF expression was localized to infiltrating monocytes/macrophages as well as to endothelium covering the coronary lesions. The finding of TF antigen present in endothelial cells in vivo is striking. Whereas TF expression in cultured endothelial cells has been demonstrated to occur in response to a variety of stimuli in vitro (reviewed in Ref. 44 ), little evidence has been presented that TF is generated by vascular endothelial cells in vivo. 45-48 The relative resistance of vascular endothelial cells to the induction of TF as well as the insensitiveness of hitherto existing detection methods have been proposed to account for previous failure to demonstrate endothelial TF expression in vivo. By use of a novel laser-assisted cell-picking technique and subsequent oligo-cell RT-PCR, we were able to identify TF mRNA in microdissected endothelial cells. The observation that TF mRNA expression is significantly higher in coronary endothelial cells from transplanted hearts versus nontransplanted native hearts strongly suggests that endothelial TF synthesis occurs in the coronary intima after cardiac transplantation. The current findings are in line with recently published data demonstrating considerable local fibrin deposition in rejected human cardiac allografts due to the induction of a net procoagulant state on the endothelial cell surface. 49

TF expression in allograft vascular endothelial cells may be activated by several mechanisms implicated in the pathophysiological setting after heart transplantation and known to induce TF expression in endothelial cells, including infections, 50 hyperlipoproteinemia, 51 and ischemic injury of coronary endothelium occurring between harvest and reimplantation. 52 In addition, it seems likely that immune phenomena may play a role in TF activation of coronary endothelial cells in transplanted hearts. Stimulation of endothelial cells may occur in response to several mediators involved in the allogeneic immune reaction after transplantation, such as inflammatory cytokines, 21,22,53,54 antibodies and immune complexes, 55 and allogeneic lymphocyte reactions. 56 As apparent endothelial TF expression was observed in some, but not in all, coronary vessels of the transplanted hearts, TF activation of endothelial cells in cardiac allografts may be a heterogeneous phenomenon. This heterogeneity may be based on a local different endothelial microenvironment as well as inherent responsiveness of cells. Moreover, the chronological sequence of endothelial TF expression after cardiac transplantation remains to be elucidated. It seems possible that the appearance of TF in transplant vasculopathy is lesion dependent. At present, we do not know when TF expression occurs during transplant atherogenesis and whether the examined specimens at the time of sacrifice consist of lesions too advanced to show expression. Thus, additional studies are required to determine the chronological distribution patterns of TF in transplant vasculopathy.

Both TF mRNA and TF protein could also be detected in mononuclear cells localized in the coronary intima, adventitia, and interstitium of cardiac allografts. We previously had demonstrated that TF activation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells occurs in human cardiac allograft recipients after transplantation. 57 In addition, there is a close interaction between monocytes and endothelial cells during adhesion and transmigration of cells as well as between macrophages and lymphocytes in the rejection infiltrate, which might lead to monocyte TF activation. Both vascular endothelium as well as T lymphoctes may further enhance intravascular hypercoagulability by intercellular stimulation of monocytes. Binding of the monocyte integrin α4β1 to endothelial cells through VCAM-1, an adhesion molecule participating in vascular leukocyte adhesion and emigration in transplant vasculopathy, as well as allogeneic monocyte-lymphocyte collaboration are known to directly induce TF expression in monocytes. 24,58,59

TF antigen was detected in all stages of the vascular disease but appeared to be most prominent in early lesions of transplant vasculopathy. The relationship between TF expression within allograft coronary arteries and the development of transplant vasculopathy deserves further scrutiny. It is increasingly clear that the activation of the coagulation cascade is strongly involved in atherogenesis. 60,61 By providing a site for circulating factor VII to bind and activate the coagulation protease cascade, the abundance of TF within the vessel wall of transplant coronary arteries therefore may have implications in the process of allograft coronary artery disease. TF expression in transplant vessel intima may not only be responsible for the clotting abnormalities observed in cardiac allografts 11,12,39 with the resultant fibrin deposition as the key event in the inititation and progression of transplant vasculopathy. 16 Moreover, in addition to its role in hemostasis, TF may contribute to the development of transplant vasculopathy by other functions apart from its role in coagulation activation. Histopathological examinations of coronary arteries from human cardiac allografts have established that early intima thickening in transplant vasculopathy results predominantly from intimal migration and proliferation of medial smooth muscle cells. 1 As TF has been demonstrated to be a strong chemotactic factor for vascular smooth muscle cells, 62 TF localized in the intima of transplant coronary arteries may provide the signal that activates smooth muscle cells to migrate through the gaps in the internal elastic lamina leading to diffuse intimal thickening .

In summary, we have documented that TF is synthesized in the coronary intima of rat heart allografts after cardiac transplantation. Endothelial TF expression in cardiac allografts may promote the induction and stabilization of procoagulant activities observed in cardiac allograft vessels, and intimal TF synthesis could be proposed as a further endovascular factor as the initiating or regulatory step in transplant vasculopathy. Additional studies correlating clinical and pathological patterns of cardiac allograft vasculopathy are needed to elucidate the potential utility of TF expression as a prognostic tool to identify patients with a higher risk for development of transplant vasculopathy.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Werner Haberbosch, Max-Planck-Institut für physiologische und klinische Forschung, Kerckhoff-Klinik, Benekestrasse 2–8, D-61231 Bad Nauheim, Germany. E-mail: werner.g.haberbosch@innere.med.uni-giessen.de.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Sonderforschungsbereich 547.

References

- 1.Weis M, von Scheidt W: Cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Circulation 1997, 96:2069-2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaye MP: The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Tenth Official Report, 1993. J Heart Lung Transplant 1993, 12:541-548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao SZ, Schroeder JS, Alderman EL, Hunt SA, Valantine HA, Wiederhold V, Stinson EB: Prevalence of accelerated coronary artery disease in heart transplant survivors: comparison of cyclosporine and azathioprine regimens. Circulation 1989, 80:100-105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakim M, Wallwork J, English T: Cyclosporin A in cardiac transplantation: medium-term results in 62 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 1988, 46:495-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billingham ME: Cardiac transplant atherosclerosis. Transplant Proc 1987, 19:19-25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hruban RH, Beschorner WE, Baumgartner WA, Augustine SM, Reitz BA, Hutchins GM: Accelerated arteriosclerosis in heart transplant recipients: an immunopathology study of 22 transplanted hearts. Transplant Proc 1991, 223:1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louie HW, Pang M, Lewis W, Drinkwater DC, Laks H: Immunhistochemical analysis of accelerated graft atherosclerosis in cardiac transplantation. Curr Surg 1989, 46:479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paavonen T, Mennander A, Lautenschlager I, Mattila S, Hayry P: Endothelialitis and accelerated arteriosclerosis in human heart transplant coronaries. J Heart Lung Transplant 1993, 12:117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wenke K, Meiser B, Thiery J, Nagel D, Scheidt Wv, Steinbeck G, Seidel D, Reichart B: Simvastatin reduces graft vessel disease and mortality after heart transplantation. Circulation 1997, 96:1398-1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao SZ, Alderman EL, Schroeder JS, Silverman JF, Hunt SA: Accelerated coronary vascular disease in the heart transplant patient: coronary arteriographic findings. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988, 12:334-340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faulk WP, Labarrere CA: Vascular immunopathology and atheroma development in human allografted organs. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992, 116:1337-1344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labarrere CA, Pitts D, Nelson DR, Faulk W: Page vascular tissue plasminogen activator and the development of coronary artery disease in heart-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 1995, 333:1111-1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbustini E, Roberts WC: Morphological observations in the epicardial coronary arteries and their surroundings late after cardiac transplantation. Am J Cardiol 1996, 78:814-820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabbani LE, Loscalzo J: Recent observations on the role of hemostatic determinants in the development of the atherothrombotic plaque. Atherosclerosis 1994, 105:1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss RH, Maduri M: The mitogenic effect of thrombin in vascular smooth muscle cells is largely due to basic fibroblast growth factor. J Biol Chem 1993, 268:5724-5727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith EB, Thompson WD: Fibrin as a factor in atherogenesis. Thromb Res 1994, 73:1-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nemerson Y: Tissue factor and hemostasis. Blood 1988, 71:71-78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilcox JN, Smith KM, Schwartz SM, Gordon D: Localization of tissue factor in the normal vessel wall and in the atherosclerotic plaque. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989, 86:2839-2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS: Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues. Am J Pathol 1989, 134:1089-1097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarpati EM, Sadler JE: Regulation of endothelial cell coagulation properties. J Biol Chem 1989, 264:20705-20713 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nawroth PP, Handley DA, Esmon CT, Stern DM: Interleukin 1 induces endothelial cell procoagulant activity while suppressing cell-surface anticoagulant activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986, 83:3460-3464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bierhaus A, Zhang Y, Deng Y, Mackman N, Quehenberger P, Haase M, Luther T, Müller M, Böhrer H, Greten J, Eike M, Bauerle P, Waldherr R, Kisiel W, Ziegler R, Stern DM, Nawroth PP: Mechanism of the TNFα mediated induction of endothelial tissue factor. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:26419-26432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edgington TS, Mackman N, Brand K, Ruf W: The structural biology of expression and function of tissue factor. Thromb Haemost 1991, 66:67-79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan S-T, Mackman N, Cui M-Z, Edgington TS: Integrin regulation of an inflammatory effector gene: direct induction of the tissue factor promoter by engagement of β1 or α4 integrin chains. J Immunol 1995, 154:3266-3274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregory SA, Kornbluth RS, Helin H, Remold HG, Edgington TS: Monocyte pro-coagulant inducing factor: a lymphokine involved in the T-cell instructed monocyte pro-coagulant response to antigen. J Immunol 1986, 141:3231-3239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloem LJ, Chen L, Konigsberg WH, Bach R: Serum stimulation of quiescent human fibroblasts induces the synthesis of TF mRNA followed by the appearance of tissue factor antigen and procoagulant activity. J Cell Physiol 1989, 139:418-423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taubman MB, Marmur JD, Rosenfield C-L, Guha A, Nichtberger S, Nemerson Y: Agonist-mediated tissue factor expression in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells: role of Ca2+ mobilization and protein kinase C activation. J Clin Invest 1993, 91:547-552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heron I: A technique for accessory cervical heart transplantation in rabbits and rats. Acta Pathol Scand 1973, 79:366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordell JL, Falini B, Erber WN, Gosh AK, Abdulaziz Z, MacDonald S, Pulford KAF, Stein H, Mason DY: Immunoenzymatic labelling of monoclonal antibodies using immune complexes of alkaline phosphatase and monoclonal anti-alkaline phosphatase (APAAP complexes). J Histochem Cytochem 1984, 32:219-229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarris GE, Mitchell RS, Billingham ME, Glasson JR, Cahill PD, Miller DC: Inhibition of accelerated cardiac allograft arteriosclerosis by fish oil. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989, 97:841-855 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lurie KG, Billingham ME, Jamieson SW, Harrison DC, Reitz BA: Pathogenesis and prevention of graft atherosclerosis in an rat experimental heart transplantation model. Transplantation 1981, 31:41-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawashe AB, Paolo G, Ambrosio G, Migliaccio F, Ragni M, Immacolata P, Chiariello M, Bach R, Garen A, Konigsberg WK, Ezekowitz MD: A monoclonal antibody against rabbit tissue factor inhibits thrombus formation in stenotic injured rabbit carotid arteries. Circ Res 1994, 74:56-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwok S: Procedures to minimize PCR-product carryover. Innis MA Gelfand DH Snisky JJ White TJ eds. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. 1990, :pp 142-145 Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker I, Becker HF, Röhrl HH, Höfler H: Laser-assisted preparation of single-cells from stained histological slides. Histochem Cell Biol 1997, 108:448-451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schütze K, Lahr G: Identification of expressed genes by laser-mediated manipulation of single cells. Nature Biotechnol 1998, 16:737-742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brady G, Iscove NN: Construction of cDNA libraries from single cells. Methods Enzymol 1993, 225:661-623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams DH, Tilney NL, Collins JJJ, Karnovsky MJ: Experimental graft arteriosclerosis. Transplantation 1992, 53:1115-1119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Billingham ME: Histopathology of graft coronary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992, 11:S38-S44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labarrere CA, Pitts D, Halbrook H, Faulk WP: Tissue plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and fibrin as indexes of clinical course in cardiac allograft recipients: an immunocytochemical study. Circulation 1994, 89:1599-1608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bach RR: Initiation of coagulation by tissue factor. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 1988, 23:339-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osterud B, Flaestad T: Increased tissue thromboplastin activity in monocytes of patients with meningococcal infection: related to an unfavorable prognosis. Thromb Haemost 1983, 49:5-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao LVM: Tissue factor as a tumor procoagulant. Cancer Metastasis Rev 1992, 11:249-266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor FBJ, Chang A, Ruf W, Morrissey JH, Hinshaw L, Catlett R, Blick K, Edgington TS: Lethal E. coli septic shock is prevented by blocking tissue factor with monoclonal antibody. Circ Shock 1991, 33:127-134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camerer E, Kolsto A, Prydz H: Cell biology of tissue factor, the principal initiator of blood coagulation. Thromb Res 1996, 81:1-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatakeyama K, Asada Y, Marutsuka K, Sato Y, Kamikubo Y, Sumiyoshi A: Localization and activity of tissue factor in human aortic atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis 1997, 133:213-219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Contrino J, Hair G, Kreutzer DL, Rickles FR: In situ detection of tissue factor in vascular endothelial cells: correlation with the malignant phenotype of human breast disease. Nature Med 1996, 2:209-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thiruvikraman SV, Guha A, Roboz J, Taubman MB, Nemerson Y, Fallon JT: In situ localization of tissue factor in human atherosclerotic plaques by binding of digoxigenin-labeled factors VIIa and X. Lab Invest 1996, 75:451-461 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drake TA, Cheng J, Chang A, Taylor FBJ: Expression of tissue factor, thrombomodulin, and E-selectin in baboons with lethal Escherichia coli sepsis. Am J Pathol 1993, 142:1458-1470 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salom RN, Maguire JA, Hancock WW: Endothelial activation and cytokine expression in human acute cardiac allograft rejection. Pathology 1998, 30:24-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colcucci M, Balconi G, Lorenzet R, Pietra A, Locati D, Donati MB, Semeraro N: Cultured human endothelial cells generate tissue factor in response to endotoxin. J Clin Invest 1983, 71:1893-1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drake TA, Hannani K, Fei HH, Lavi S, Berliner JA: Minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces tissue factor expression in cultured human endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 1991, 138:601-607 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gertler JP, Weibe DA, Ocasio VH, Abbott WM: Hypoxia induces procoagulant activity in cultured human venous endothelium. J Vasc Surg 1991, 1991:428-433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carlsen E, Flatmark A, Prydz H: Cytokine-induced procoagulant activity in monocytes and endothelial cells: further enhancement by cyclosporine. Transplantation 1988, 46:575-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clauss M, Gerlach M, Gerlach H, Brett J, Wang F, Familletti PC, Pan YC, Olander JV, Connolly DT, Stern D: Vascular permeability factor: a tumor-derived polypeptide that induces endothelial cell and monocyte procoagulant activity and promotes monocyte migration. J Exp Med 1990, 172:535-545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tannenbaum SH, Finko R, Cines DB: Antibody and immune complexes induce tissue factor production by human endothelial cells. J Immunol 1986, 137:1532-1537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyberg T, Galdal KS, Evensen SA, Prydz H: Cellular cooperation in endothelial cell thromboplastin synthesis. Br J Haematol 1983, 53:85-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hölschermann H, Kohl O, Maus U, Dürfeld F, Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP, Lohmeyer J, Tillmanns H, Haberbosch W: Cyclosporine inhibits monocyte tissue factor activation in cardiac transplant recipients. Circulation 1997, 96:4232-4238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Helin H, Edgington TS: Allogeneic induction of the human T cell-instructed monocyte procoagulant response is rapid and is elicited by HLA-DR. J Exp Med 1983, 158:962-975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferreira OC, Jr, Barcinski MA: Autologous induction of the human T-cell-dependent monocyte procoagulant activity: a possible link between immunoregulatory phenomena and blood coagulation. Cell Immunol 1986, 101:259-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanaka K, Sueishi K: Biology of disease: the coagulation and fibrinolysis systems and atherosclerosis. Lab Invest 1993, 69:5-18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson WD, Smith EB: Atherosclerosis and the coagulation system. J Pathol 1989, 159:97-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sato Y, Asada Y, Marutsuka K, Hatakeyama K, Sumiyoshi A: Tissue factor induces migration of cultured aortic smooth muscle cells. Thromb Haemost 1996, 75:389-392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]