Abstract

Mesangial cell proliferation and matrix accumulation, driven by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), contribute to many progressive renal diseases. In a novel approach to antagonize PDGF, we investigated the effects of a nuclease-resistant high-affinity oligonucleotide aptamer in vitro and in vivo. In cultured mesangial cells, the aptamer markedly suppressed PDGF-BB but not epidermal- or fibroblast-growth-factor-2-induced proliferation. In vivo effects of the aptamer were evaluated in a rat mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis model. Twice-daily intravenous (i.v.) injections from days 3 to 8 after disease induction of 2.2 mg/kg PDGF-B aptamer, coupled to 40-kd polyethylene glycol (PEG), led to 1) a reduction of glomerular mitoses by 64% on day 6 and by 78% on day 9, 2) a reduction of proliferating mesangial cells by 95% on day 9, 3) markedly reduced glomerular expression of endogenous PDGF B-chain, 4) reduced glomerular monocyte/macrophage influx on day 6 after disease induction, and 5) a marked reduction of glomerular extracellular matrix overproduction (as assessed by analysis of fibronectin and type IV collagen) both on the protein and mRNA level. The administration of equivalent amounts of a PEG-coupled aptamer with a scrambled sequence or PEG alone had no beneficial effect on the natural course of the disease. These data show that specific inhibition of growth factors using custom-designed, high-affinity aptamers is feasible and effective.

Specific inhibition of growth factors and cytokines has become a major goal in experimental and clinical medicine. However, this approach is often hampered by the lack of specific pharmacological antagonists. Available alternative approaches are also limited, as neutralizing antibodies often show a low efficacy in vivo and may be immunogenic, and as in vivo gene therapy for these purposes is still in its infancy. In the present study we have investigated a novel approach to specifically inhibit growth factors in vivo, namely, the use of aptamers produced by the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) method. 1,2 The SELEX method has recently emerged as a powerful tool for screening large sequence-randomized nucleic acid libraries for unique oligonucleotides (aptamers) that bind to various other molecules with high affinity and specificity. For the purpose of this study, we have targeted platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), the role of which is particularly well established in cardiovascular and renal disease. 3,4

A large variety of progressive renal diseases is characterized by glomerular mesangial cell proliferation and matrix accumulation. 5 PDGF B-chain appears to have a central role in driving both of these processes given that 1) mesangial cells produce PDGF in vitro and various growth factors induce mesangial cell proliferation via induction of auto- or paracrine PDGF B-chain excretion, 2) PDGF B-chain and its receptor are overexpressed in many glomerular diseases, 3) infusion of PDGF-BB or glomerular transfection with a PDGF B-chain cDNA can induce selective mesangial cell proliferation and matrix accumulation in vivo, and 4) PDGF B-chain or β-receptor knock-out mice fail to develop a mesangium (reviewed in Ref. 4 ).

So far only one study has examined the effect of inhibition of PDGF B-chain in renal disease; Johnson et al, using a neutralizing polyclonal antibody to PDGF, were able to reduce mesangial cell proliferation and matrix accumulation in a rat model of mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. 6 In this model, injection of an anti-mesangial cell antibody (anti-Thy-1.1) results in complement-dependent lysis of the mesangial cells, followed by an overshooting reparative phase that resembles human mesangioproliferative nephritis. 7 Limitations of the study of Johnson et al 6 included the necessity to administer large amounts of heterologous IgG and a limitation of the study duration to 4 days due to concerns that the heterologous IgG might elicit a humoral immune reaction. In the present study we have therefore used the anti-Thy-1.1 nephritis model to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of inhibiting PDGF B-chain in vivo with high-affinity DNA-based aptamers.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of High-Affinity DNA-Based Aptamers to the PDGF B-Chain

All aptamers and their sequence-scrambled controls were synthesized by the solid-phase phosphoramidite method on controlled pore glass using an 8800 Milligen DNA synthesizer and deprotected using ammonium hydroxide at 55°C for 16 hours. 2-Fluoropyrimidine nucleoside phosphoramidites were obtained from JBL Scientific (San Luis Obispo, CA). 2′-O-Methylpurine phosphoramidites were obtained from PerSeptive Biosystems (Boston, MA). Hexaethylene glycol (18-atom) spacer was obtained from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). All other nucleoside phosphoramidites were from PerSeptive Biosystems. To prolong the in vivo half-time of the aptamers in plasma, they were coupled to 40-kd polyethylene glycol (PEG). The covalent coupling of PEG to the aptamer (or to its sequence-scrambled control) was accomplished by treating 40-kd PEG N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Shearwater Polymers, Huntsville, AL) with a primary amine group introduced at the 5′ end of the aptamer using trifluoroacetyl-protected pentylamine phosphoramidite. All PEG-aptamer conjugates were purified by anion exchange followed by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). The binding affinities of various aptamers for PDGF-AB or -BB (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were determined by the nitrocellulose filter binding method 8 or by the competition electrophoresis mobility shift assay. 9

Cloning and Expression of Rat PDGF-BB

Rat PDGF-BB for cross-reactivity binding experiments was derived from Escherichia coli transfected with sCR-Script Amp SK(+) plasmid containing the rat PDGF-BB sequence. Rat PDGF-BB sequence was derived from rat lung poly A+ RNA (Clontech, San Diego, CA) through reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using primers that amplify sequence encoding the mature form of PDGF-BB. Rat PDGF-BB protein expression and purification was performed at R&D Systems.

Stability of Aptamers in Rat Plasma in Vitro and in Vivo

The stabilities of DNA-based aptamers in vitro were examined in rat serum at 37°C. Serum was obtained from a Sprague-Dawley rat and was filtered through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate filter and buffered with 20 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer. Test ligands were added to the serum at the final concentration of 500 nmol/L. The final serum concentration was 85% as a result of the addition of buffer and aptamer. From the original 900-μl incubation mixture, 100-μl aliquots were withdrawn at various time points and added to 10 μl of 500 mmol/L EDTA (pH 8.0), mixed and frozen on dry ice, and stored at −20°C until the end of the experiment. The amount of full-length oligonucleotide ligand remaining at each of the time points was quantitated by HPLC analysis. To prepare the samples for HPLC injections, 200 μl of a mixture of 30% formamide, 70% 25 mmol/L Tris buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1% acetonitrile was added to 100 μl of thawed time point samples, mixed for 5 seconds, and spun for 20 minutes at 14,000 rpm in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge. The analysis was performed using an anion exchange chromatography column (NuceoPac, Dionex, PA-100, 4 × 50 mm) applying a LiCl gradient. The amount of full-length oligonucleotide remaining at each time point was determined from the peak areas.

Pharmacokinetics of the Modified PDGF Aptamer Conjugated to 40-kd PEG in Vivo

The pharmacokinetic properties of the modified PDGF aptamer conjugated to 40-kd PEG were determined in Sprague-Dawley rats. Before animal dosing, the aptamer was diluted with sterile PBS from a stock solution (also in sterile PBS), to final concentrations between 1 and 2 mg/ml (based on oligonucleotide molecular weight and the ultraviolet absorption at 260 nm with an extinction coefficient of 0.037 per mg oligo/ml). A single dose of the aptamer was administered to three Sprague-Dawley rats by i.v. bolus injection through the tail vein. Blood samples (approximately 400 μl) were obtained by venipuncture under isofluorane anesthesia and placed in EDTA-containing tubes. The EDTA blood samples were immediately processed by centrifugation to attain plasma and stored frozen at ≤−20°C. Time points for blood sample collection ranged from 2 to 480 minutes

To prepare plasma samples for HPLC analysis, 200 μl of methanol was added to 100 μl of plasma sample, mixed for 30 seconds, and spun in a centrifuge for 10 minutes at 15,000 × g. All of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and dried under vacuum. Samples were resuspended by addition of 100 μl of 50% formamide and 4% perchloric acid, mixed, and spun as described above. Ninety microliters of supernatant was transferred to a 250-μl limited-volume insert vial for HPLC analysis. Samples were analyzed by anion exchange HPLC (DNAPac PA-100, 4 × 50 mm) with LiCl gradient elution in 30% formamide and monitoring of ultraviolet absorption at 270 nm. Aptamer concentrations were determined based on peak area from a standard curve of the PEG-aptamer conjugate. The HPLC-based analysis described here and the double hybridization analysis described previously 9 have produced comparable results for a similar aptamer conjugated to 40-kd PEG (specific binding to vascular endothelial growth factor, Stanley C. Gill, unpublished observations), suggesting that the HPLC analysis indicates the levels of undegraded (full-length) aptamer. Nevertheless, as the PEG moiety has a strong influence on the HPLC retention times of the PEG-aptamer conjugate, we have not at this time ruled out the possibility that some of the partially degraded aptamer may migrate with a similar retention time as the full-length aptamer.

Mesangial Cell Culture Experiments

Human and rat mesangial cells were established in culture, characterized, and maintained as described previously. 10 To examine the antiproliferative effect of the aptamers on the cultured mesangial cells, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) and grown to subconfluency. They were then growth-arrested for 48 hours in MCDB 302 medium (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) (human mesangial cells) or RPMI 1640 with 1% bovine serum albumin (rat mesangial cells). After 48 hours, various stimuli together with PDGF B-chain aptamer or sequence-scrambled aptamer were added: medium alone, human recombinant PDGF-AA, -AB, or -BB (kindly provided by J. Hoppe, University of Würzburg, Germany), human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF; Calbiochem, Bad Soden, Germany), or recombinant human fibroblast growth factor-2 (kindly provided by Synergen/Amgen, Boulder, CO). DNA synthesis in the rat mesangial cells was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation as described 11 after 24 hours of stimulation (of which the last 4 hours were in the presence of [3H]thymidine). In the case of human mesangial cells, after 72 hours of incubation, numbers of viable cells were determined using 2,3-bis[2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT; Sigma) as described. 12

Experimental Design

All animal experiments were approved by the local review boards. Anti-Thy-1.1 mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis was induced in 33 male Wistar rats (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) weighing 150 to 160 g by injection of 1 mg/kg monoclonal anti-Thy-1.1 antibody (clone OX-7; European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures, Salisbury, UK). Rats were treated with aptamers or PEG (see below) from days 3 to 8 after disease induction. Treatment consisted of twice-daily i.v. bolus injections of the substances dissolved in 400 μl of PBS, pH 7.4, for a total of 12 injections. The treatment duration was chosen to treat rats from ∼1 day after the onset to the peak of mesangial cell proliferation, which in the OX-7-induced anti-Thy-1.1 nephritis occurs between days 6 and 9 after disease induction. Four groups of rats were studied: 1) 9 rats that received a total of 4 mg (0.33 mg/injection) of the PDGF-B aptamer (coupled to 15.7 mg 40 kd PEG), 2) 10 rats that received an equivalent amount of PEG-coupled, scrambled aptamer, 3) 8 rats that received an equivalent amount (15.7 mg) of 40-kd PEG alone, and 4) 6 rats that received 400-μl bolus injections of PBS alone. Renal biopsies for histological evaluation were obtained on day 6 by intravital biopsy and postmortem on day 9 after disease induction. For intravital biopsies the left kidney was exposed by a flank incision under general anesthesia. A 3- to 4-mm slice was then cut off the lower pole, and bleeding was stopped immediately by gently applying a collagen sponge, followed by wound closure. As judged from serum creatinines, this biopsy technique does not disturb renal function (unpublished observations). Twenty-four-hour urine collections were performed from days 5 to 6 and 8 to 9 after disease induction. The thymidine analogue 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma; 100 mg/kg body weight) was injected intraperitoneally at 4 hours before sacrifice on day 9.

Normal ranges of proteinuria and renal histological parameters (see below) were established in 10 nonmanipulated Wistar rats of similar age.

Renal Morphology

Tissue for light microscopy and immunoperoxidase staining was fixed in methyl Carnoy’s solution 13 and embedded in paraffin. Four-micron sections were stained with the periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reagent and counterstained with hematoxylin. In the PAS-stained sections the number of mitoses within 100 glomerular tufts was determined.

Immunoperoxidase Staining

Four-micron sections of methyl Carnoy’s-fixed biopsy tissue were processed by an indirect immunoperoxidase technique as described. 13 Primary antibodies were identical to those described previously 14,15 and included a murine monoclonal antibody (clone 1A4) to α-smooth muscle actin; a murine monoclonal antibody (clone PGF-007) to PDGF B-chain; a murine monoclonal IgG antibody (clone ED1) to a cytoplasmic antigen present in monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells; affinity-purified polyclonal goat anti-human/bovine type IV collagen IgG preabsorbed with rat erythrocytes; an affinity-purified IgG fraction of a polyclonal rabbit anti-rat fibronectin antibody; plus appropriate negative controls as described previously. 14,15 Evaluation of all slides was performed by an observer who was unaware of the origin of the slides.

To obtain mean numbers of infiltrating leukocytes in glomeruli, more than 50 consecutive cross sections of glomeruli were evaluated and mean values per kidney were calculated. For the evaluation of the immunoperoxidase stains for α-smooth muscle actin and PDGF B-chain, each glomerular area was graded semiquantitatively, and the mean score per biopsy was calculated. Each score reflects mainly changes in the extent rather than intensity of staining and depends on the percentage of the glomerular tuft area showing focally enhanced positive staining: I, 0% to 25%; II, 25% to 50%; III, 50% to 75%; IV, >75%. We have recently described that data obtained using this scoring system are highly correlated with those obtained by computerized morphometry. 16,17

Immunohistochemical Double Staining

Double immunostaining for the identification of the type of proliferating cells was performed as reported previously 16,17 by first staining the sections for proliferating cells with a murine monoclonal antibody (clone BU-1) against bromodeoxyuridine-containing nuclease in Tris-buffered saline (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany) using an indirect immunoperoxidase procedure. Sections were then incubated with the IgG1 monoclonal antibodies 1A4 against α-smooth muscle actin and ED1 against monocytes/macrophages. Cells were identified as proliferating mesangial cells or monocytes/macrophages if they showed positive nuclear staining for BrdU and if the nucleus was completely surrounded by cytoplasm positive for α-smooth muscle actin or ED1 antigen. Negative controls included omission of either of the primary antibodies, in which case no double staining was noted.

In Situ Hybridization for Type IV Collagen mRNA

In situ hybridization was performed on 4-μm sections of biopsy tissue fixed in buffered 10% formalin using a digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probe for type IV collagen 18 as described. 14 Detection of the RNA probe was performed with an alkaline-phosphatase-coupled anti-digoxigenin antibody (Genius nonradioactive nucleic acid detection kit, Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) with subsequent color development. Controls consisted of hybridization with a sense probe to matched serial sections by hybridization of the antisense probe to tissue sections that had been incubated with RNAse A before hybridization or by deletion of the probe, antibody, or color solution. 15 Glomerular mRNA expression was semiquantitatively assessed using the scoring system described above.

Miscellaneous Measurements

Urinary protein was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany) and bovine serum albumin (Sigma) as a standard.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical significance (defined as P < 0.05) was evaluated using Student t-tests or analysis of variance and Bonferroni t-tests.

Results

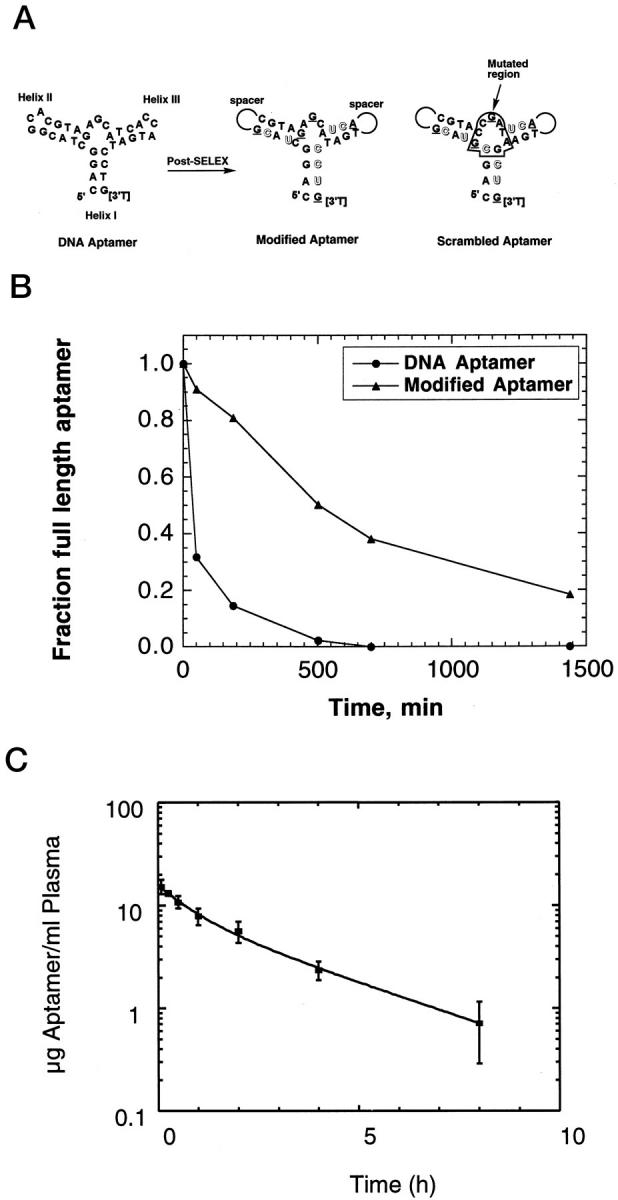

Post-SELEX Modifications in PDGF DNA Aptamers Result in Improved Nuclease Resistance

High-affinity DNA aptamers to the PDGF B-chain were identified previously by the SELEX process. 8 The consensus secondary structure motif of these aptamers is a three-way helix junction with a conserved single-stranded loop at the point of strand exchange (Figure 1A) ▶ . To improve nuclease resistance of one of the minimal aptamers (a truncated version of aptamer 36t in Ref. 8 ), we have synthesized and tested a series of 2′-O-methyl- or 2′-fluoro-substituted aptamers to identify positions that tolerate such substitutions without a loss of binding affinity. In addition to identifying a pattern of allowed 2′-O-methyl- and 2′-fluoro substitutions, we found that trinucleotide loops on helices II and III in the aptamer could be replaced with hexaethylene glycol (18-atom) non-nucleotide spacers without compromising high-affinity binding to PDGF-AB or -BB (Figure 1A) ▶ . This finding is in agreement with the notion that the helix junction domain of the aptamer represents the core of the structural motif required for high-affinity binding. 8 In practical terms, the replacement of six nucleotides with two spacers is advantageous in that it reduces by four the number of coupling steps required for the synthesis of the aptamer. Another support for the importance of helix junction domain in binding comes from the control aptamer, in which eight nucleotides in the helix junction region were interchanged without formally changing the consensus secondary structure (Figure 1A) ▶ . The binding affinity of this scrambled aptamer for PDGF-BB (Kd ≈ 1 μmol/L) is 10,000-fold lower compared with the binding affinity of the aptamer used in the experiments described below (Kd ≈ 0.1 nmol/L).

Figure 1.

A: Summary of post-SELEX modifications in the PDGF B-chain aptamers. Outlined and underlined letters denote 2′-fluoro and 2′-O-methyl nucleotides, respectively; spacer indicates the hexaethylene glycol linker, and [3′T] indicates an inverted (3′-3′) thymidine nucleotide used as a cap to reduce 3′ to 5′ exonuclease-mediated digestion. The mutated region of the scrambled region is boxed to accent the overall similarity to the aptamer. B: Stability of the all-DNA aptamer and the modified PDGF B-chain aptamers in rat serum at 37°C in vitro. C: Plasma concentration of modified PDGF-B aptamer conjugated to 40-kd PEG in Sprague-Dawley rats (mean ± SD; n = 3). Compartmental pharmacokinetic analysis (curve fit) was carried out using WinNonlin, version 1.5 (Scientific Consulting Apex, NC).

We next compared the stabilities of the modified aptamer and its precursor DNA aptamer in rat serum in vitro. The half-time of the modified aptamer in serum was considerably longer (∼8 hours) compared with that of its all-DNA precursor (∼0.6 hours; Figure 1B ▶ ). The observed increase in nuclease resistance is in agreement with previous studies with 2′-substituted nucleic acids. 19,20 In addition to the modifications mentioned above, for all experiments reported here, the modified DNA aptamer was conjugated to 40-kd PEG. Importantly, the addition of the PEG moiety to the 5′ end of the aptamer has no effect on the binding affinity of the aptamer for PDGF-BB (Kd ≈ 0.1 nmol/L).

Pharmacokinetics of the Modified PDGF Aptamer Conjugated to 40-kd PEG in Vivo

The concentration of the modified PDGF aptamer conjugated to 40-kd PEG in rat plasma after i.v. injection (1 mg/kg) is shown in Figure 1C ▶ . The clearance of the aptamer-PEG conjugate from plasma is biphasic with approximately 47% of the compound being cleared with a half-life of 32.4 ± 13 minutes and 53% of the compound being cleared with a half-life of 134.5 ± 13 minutes. The concentration of the aptamer in rat plasma after the i.v. injection is 16 μg/ml (1.6 μmol/L) at t = 0 and 0.21 μg/ml (21 nmol/L) at t = 12 hours (extrapolated). Thus, to a first approximation and assuming a linear increase in plasma concentration of the aptamer at the higher injected dose in the experiments described below (2.1 to 2.2 mg/kg i.v. every 12 hours), the aptamer concentration during the treatment period was not lower than 40 nmol/L (ie, 0.4 μg/ml).

Cross-Reactivity of Aptamers for Rat PDGF-BB

The sequence of PDGF is highly conserved among species, and human and rat PDGF B-chain sequences are 89% identical. 21,22 Nevertheless, in view of the high specificity of aptamers, 23 the correct interpretation of the in vivo experiments requires understanding of the binding properties of the aptamers to rat PDGF B-chain. We have therefore cloned and expressed the mature form of rat PDGF-BB in E. coli. Based on nitrocellulose filter binding experiments, the PDGF aptamers bound to rat and human recombinant PDGF-BB with the same affinity (Kd ≈ 0.1 nmol/L).

PDGF B-Chain DNA-Aptamer Specifically Inhibits PDGF-BB-Induced Rat and Human Mesangial Cell Proliferation in Vitro

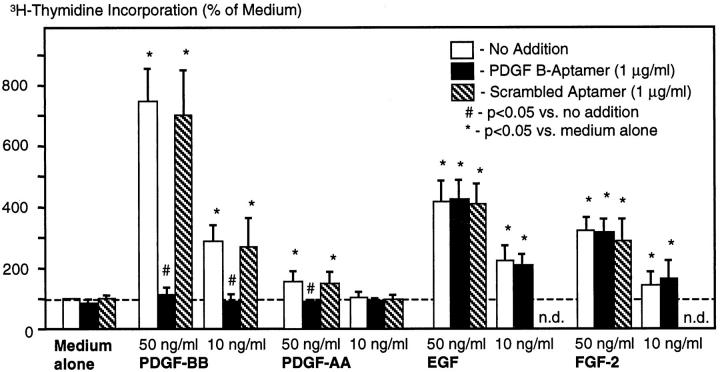

In growth-arrested rat mesangial cells, the effects of the PDGF-B aptamer or the scrambled aptamer on mitogen-induced proliferation were tested. Stimulated growth rates of the cells were not affected by the addition of scrambled aptamer (Figure 2) ▶ . At a concentration of 1 μg/ml the PDGF-B aptamer completely inhibited the PDGF-BB- and -AA-induced growth but had no effect on EGF- or FGF-2-induced growth (Figure 2) ▶ . In an additional experiment we also documented a 84% inhibition of the mesangial cell growth induced by 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB at an aptamer concentration of 0.5 μg/ml, ie, the minimal aptamer level achieved in vivo (see above). Inhibition of PDGF-BB-induced growth by the PDGF-B aptamer was not due to cell death as evidenced by trypan blue exclusion of the cells. Furthermore, using morphological criteria, in particular, nuclear condensation, no evidence for mesangial cell apoptosis was noted under these conditions.

Figure 2.

Effects of PDGF-B aptamer on mitogen-stimulated DNA synthesis of rat mesangial cells in culture. Data are 4-hour [3H]thymidine incorporation rates and are expressed as percentage of baseline incorporation (medium alone with no addition, 1373 ± 275 cpm). Data are means ± SD of five independent experiments.

Using the XTT assay (Table 1) ▶ , the PDGF-B aptamer also completely inhibited PDGF-BB-induced human mesangial cell growth. PDGF-AB- and -AA-induced mesangial cell growth also tended to be lower with the PDGF-B aptamer, but these differences failed to reach statistical significance. In contrast, no effects of the PDGF-B aptamer on either EGF- or FGF-2-induced growth were noted (Table 1) ▶ . Similar effects were noted if the aptamers were used at a concentration of 10 μg/ml (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effects of PDGF-B Aptamer on Mitogen-Stimulated Proliferation of Human Mesangial Cells in Culture

| Medium | PDGF-BB | PDGF-AB | PDGF-AA | EGF | FGF-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDGF-B aptamer (50 μg/ml) | 98 ± 23 | 108 ± 15* | 76 ± 34 | 100 ± 29 | 159 ± 14 | 162 ± 20 |

| Scrambled aptamer (50 μg/ml) | 88 ± 19 | 228 ± 65 | 123 ± 36 | 142 ± 41 | 160 ± 21 | 163 ± 38 |

| 40-kd PEG alone | 100 ± 0 | 218 ± 92 | 159 ± 40 | 142 ± 56 | 155 ± 33 | 174 ± 22 |

All mitogens were added at 100 ng/ml final concentration. Data are optical densities measured in the XTT assay and are expressed as percentages of baseline, ie, cells stimulated with medium plus 200 μg/ml 40-kd PEG (ie, the amount equivalent to the PEG attached to 50 μg/ml aptamer). Results are means ± SD of five separate experiments (n = 3 in the case of medium plus 40-kd PEG; statistical evaluation was therefore confined to the PDGF-B and scrambled aptamer groups.

*P < 0.05 versus scrambled aptamer.

Effects of PDGF B-Chain DNA-Aptamer in Rats with Anti-Thy-1.1 Nephritis

After the injection of anti-Thy-1.1 antibody, PBS-treated animals developed the typical course of the nephritis, which is characterized by early mesangiolysis and followed by a phase of mesangial cell proliferation and matrix accumulation on days 6 and 9. No obvious adverse effects were noted after the repeated injection of aptamers or PEG alone, and all rats survived and appeared normal until the end of the study.

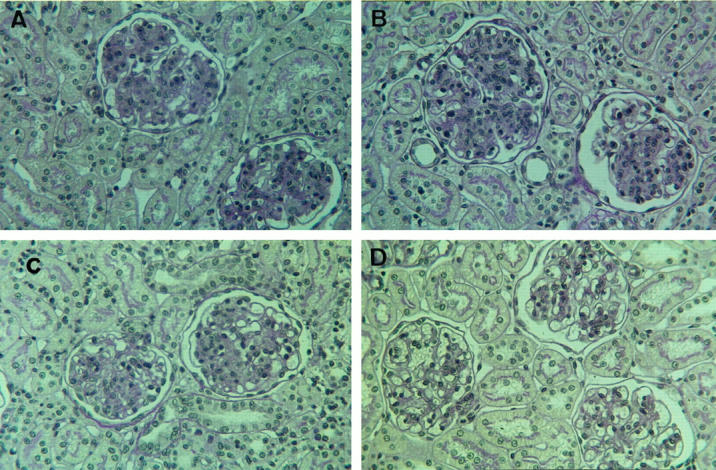

In PAS-stained renal sections the mesangioproliferative changes on days 6 and 9 after disease induction were severe and indistinguishable among rats receiving PBS, PEG alone, or the scrambled aptamer (Figure 3 ▶ , A to C). Histological changes were markedly reduced in the PDGF-B aptamer-treated group (Figure 3D) ▶ . To evaluate the mesangioproliferative changes, various parameters were analyzed.

Figure 3.

Representative PAS-stained renal sections at day 9 after disease induction of mesangioproliferative nephritis of a rat receiving PBS alone (A), 40-kd PEG alone (B), scrambled aptamer coupled to 40-kd PEG (C), or PDGF-B aptamer coupled to 40-kd PEG (D). Compared with the three control rats shown in A to C, the PDGF-B aptamer-treated rat exhibits an almost normal glomerular morphology, ie, markedly reduced glomerular hypercellularity and mesangial matrix accumulation. Magnification, ×400.

Reduction of Mesangial Cell Proliferation

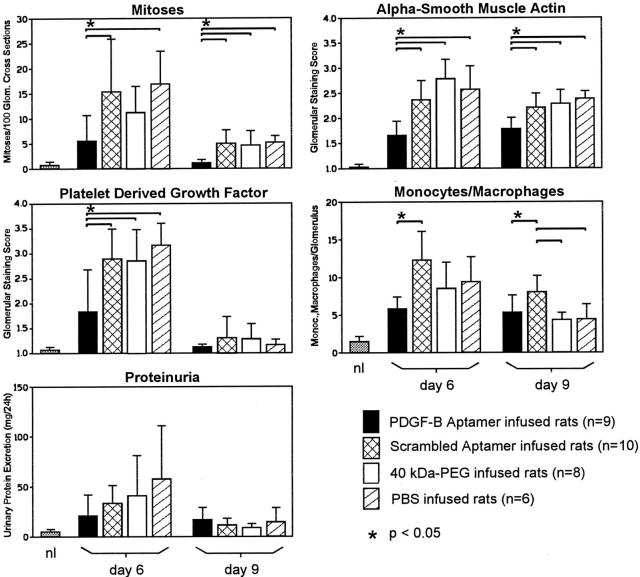

Glomerular cell proliferation, as assessed by counting the number of glomerular mitoses, was not significantly different between the three control groups on days 6 and 9 (Figure 4) ▶ . Compared with rats receiving the scrambled aptamer, treatment with PDGF-B aptamer led to a reduction of glomerular mitoses by 64% on day 6 and by 78% on day 9 (Figure 4) ▶ . To assess the treatment effects on mesangial cells, we immunostained the renal sections for α-smooth muscle actin, which is expressed by activated mesangial cells only. 24 Again, there were no significant differences between the three control groups on days 6 and 9. However, the immunostaining scores of α-smooth muscle actin were significantly reduced on days 6 and 9 in the PDGF-B aptamer-treated group (Figure 4) ▶ . To specifically determine whether mesangial cell proliferation was reduced, we double immuno-stained PDGF-B aptamer-treated rats and scrambled aptamer-treated rats for a cell proliferation marker (BrdU) and α-smooth muscle actin. The data confirmed a marked decrease of proliferating mesangial cells on day 9 after disease induction: 2.2 ± 0.8 BrdU-positive/α-smooth-muscle-actin-positive cells per 100 glomerular cross sections in PDGF-B aptamer-treated rats versus 43.3 ± 12.4 cells in rats receiving the scrambled aptamer, ie, a 95% reduction of mesangial cell proliferation (Figure 5) ▶ . In contrast, no effect of the PDGF-B aptamer was noted on proliferating monocytes/macrophages on day 9 after disease induction (PDGF-B aptamer-treated rats: 2.8 ± 1.1 BrdU+/ED-1+ cells per 100 glomerular cross sections; scrambled aptamer-treated rats: 2.7 ± 1.8).

Figure 4.

Effects of PDGF-B aptamer on glomerular cell proliferation, mesangial cell activation (as assessed by glomerular de novo expression of α-smooth muscle actin), expression of glomerular PDGF B-chain, monocyte/macrophage influx, and proteinuria in rats with anti-Thy-1.1 nephritis. nl = values observed in 10 normal rats.

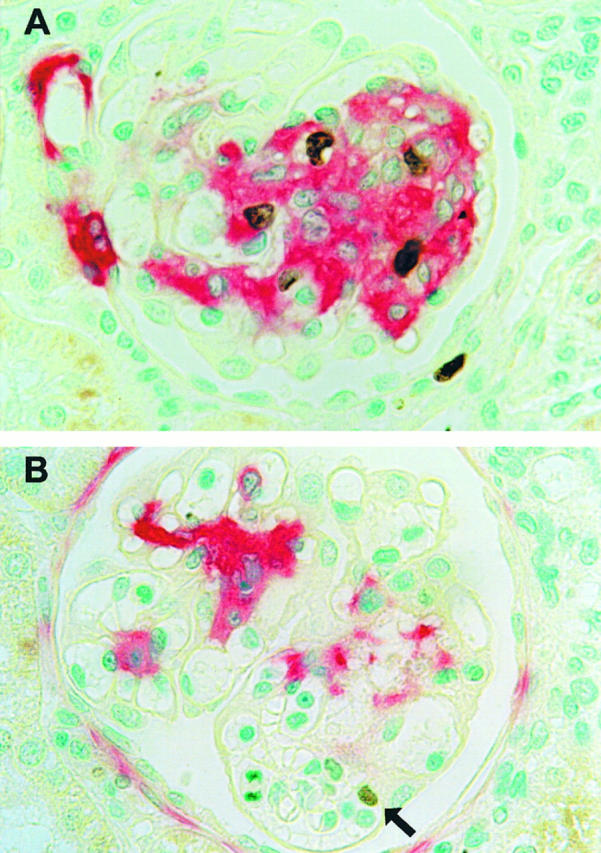

Figure 5.

Effects of PDGF-B aptamer on glomerular mesangial cell proliferation as assessed by double immunostaining for nuclei incorporating the thymidine analogue BrdU and the mesangial cell de novo expression of α-smooth muscle actin on day 9 after disease induction. In a rat receiving scrambled DNA aptamer (A), marked glomerular de novo expression of α-smooth muscle actin (red stain) is noted, and at least three glomerular cells with a BrdU-positive nucleus (brown stain) exhibit an α-smooth muscle actin-positive cytoplasm, indicating that they are proliferating mesangial cells. In a rat receiving PDGF-B aptamer (B), little glomerular de novo expression of α-smooth muscle actin (red stain) is noted, and only one glomerular cell, which is α-smooth muscle actin negative, shows weak nuclear BrdU staining (arrow). Magnification, ×400.

Reduced Expression of Endogenous PDGF B-Chain

By immunohistochemistry the glomerular PDGF B-chain expression was markedly up-regulated in all three control groups (Figure 4) ▶ , similar to previous observations. 15 In the PDGF-B aptamer-treated group the glomerular overexpression of PDGF B-chain was significantly reduced in parallel with the reduction of proliferating mesangial cells (Figure 4) ▶ . This reduction was not due to masking of the PDGF B-chain epitope recognized by the anti-PDGF B-chain antibody, as the immunostaining intensity was not affected in renal sections that had been preincubated with the PDGF-B aptamer (immunostaining scores in sections preincubated with buffer, 2.70; with PDGF-B aptamer, 2.97; with scrambled aptamer, 2.78; means of two experiments each).

Reduction of Glomerular Monocyte/Macrophage Influx

The glomerular monocyte/macrophage influx was significantly reduced in the PDGF aptamer-treated rats as compared with rats receiving scrambled aptamer on days 6 and 9 after disease induction (Figure 4) ▶ .

Effects on Proteinuria

Moderate proteinuria of up to 147 mg/24 hours was present on day 6 after disease induction in the three control groups (Figure 4) ▶ . Treatment with the PDGF-B aptamer reduced the mean proteinuria on day 6, but this failed to reach statistical significance (Figure 4) ▶ . Proteinuria on day 9 after disease induction was low and similar in all four groups (Figure 4) ▶ .

Reduction of Glomerular Matrix Production and Accumulation

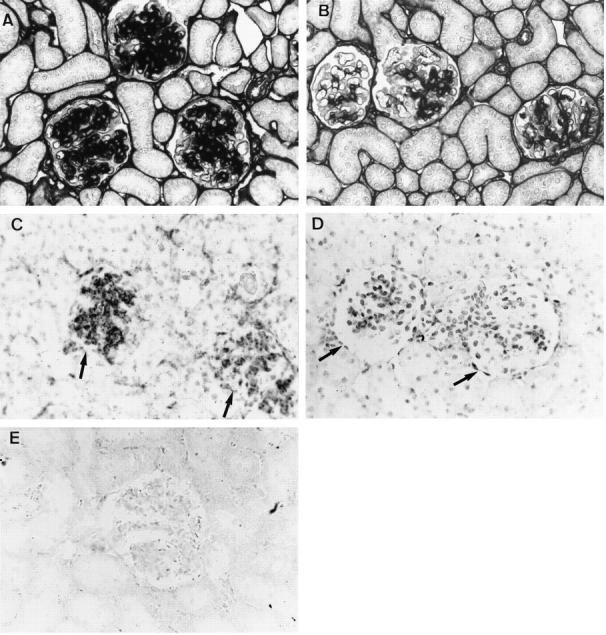

By immunohistochemistry, marked glomerular accumulation of type IV collagen and fibronectin was noted in all three control groups (Figure 6) ▶ . The overexpression of both glomerular type IV collagen and fibronectin was significantly reduced in PDGF-B aptamer-treated rats (Figure 6) ▶ . By in situ hybridization, the decreased glomerular protein expression of type IV collagen in PDGF-B aptamer-treated rats was shown to be associated with decreased glomerular synthesis of this collagen type (Figure 6) ▶ . Sense controls for the in situ hybridizations were negative and similar to those published recently 25 (Figure 6E) ▶ .

Figure 6.

Effects of PDGF-B aptamer on glomerular matrix accumulation. Glomerular immunohistochemical accumulation of type IV collagen on day 9 is massive in rats receiving scrambled aptamer (A) and markedly reduced in rats receiving PDGF-B aptamer (B). Magnification, ×400. Similarly, the expression of type IV mRNA, as assessed by in situ hybridization, is pronounced in glomeruli (arrows) of rats receiving scrambled aptamer (C) and low in glomeruli (arrows) of rats receiving PDGF-B aptamer (D); no specific signal is observed in a section hybridized with a sense control (E). Magnification, ×400.

Discussion

In the anti-Thy-1.1 nephritis model, immunological damage to the mesangium, resulting in mesangiolysis, occurs during the first 24 to 48 hours after disease induction. 13,26 Subsequently, nondamaged mesangial cells immigrate from the extraglomerular mesangium and proliferate, giving rise to the pathological picture of mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. 7,27 Given this course of the nephritis, we initiated treatment on the 3rd day to avoid any interference of the therapy with pathomechanisms involved in disease induction, eg, glomerular binding of the nephritogenic antibody, complement activation, or cytotoxic damage, all of which peak during the 1st day of the disease. Furthermore, this experimental design enhances the clinical relevance of the study, as treatment was instituted after the onset of mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis.

The major finding of the present study was that treatment with PDGF-B aptamer from days 3 to 9 after disease induction resulted in a near complete arrest of the overshooting mesangial cell proliferation and thereby led to a marked reduction of glomerular hypercellularity. Further support for the reduction of mesangial cell proliferation is provided by the observations that the glomerular de novo expression of α-smooth muscle actin and the overexpression of PDGF B-chain were also significantly inhibited by the PDGF-B aptamer. Both of these proteins are selectively up-regulated in activated mesangial cells in the anti-Thy-1.1 model, 15,24 and consequently, any intervention that reduces mesangial cell hyperplasia should also reduce expression of these proteins. It is of interest to note that mesangial cell proliferation as assessed by double immunostaining for BrdU and α-smooth muscle actin expression was reduced by 95% although glomerular mitoses were reduced by only 78% on day 9. This discrepancy suggests that proliferation of other glomerular cells may be independent of PDGF (as demonstrated, for example, by the determination of proliferating monocytes/macrophages) and lends support to the highly specific action of the PDGF-B aptamer.

In addition to selectively abrogating mesangial cell proliferation, treatment with the PDGF-B aptamer also reduced the glomerular monocyte/macrophage influx and accumulation of extracellular matrix. Both of these latter processes are known to depend to a large degree on other cytokines produced by activated mesangial cells: glomerular macrophage influx on the production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 28 and matrix overproduction on the release of transforming growth factor-β. 29 The present data therefore suggest that PDGF B-chain is either linked to the mesangial cell production of these latter cytokines, as indicated by cell culture studies, 30 or that PDGF B-chain is directly and independently involved in chemotaxis and matrix production. Regardless of these issues, the present study establishes the release of PDGF B-chain as a central pathogenetic event in the development of mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. Our data also suggest that macrophage- or platelet-derived PDGF is unlikely to play a major role in the mediation of mesangioproliferative changes in this model, as influx of both cell types peaks at ∼24 hours, 13 ie, 2 days before the initiation of anti-PDGF treatment.

Similar, albeit quantitatively somewhat lower, effects were also noted in our previous study with a neutralizing antibody to PDGF B-chain in the anti-Thy-1.1 nephritis model; treatment resulted in a 57% reduction of glomerular cell proliferation on day 4 and reduced glomerular matrix accumulation by approximately one score point. 6 One important concern in that study was that large amounts of IgG (600 mg/kg/day), both neutralizing anti-PDGF antibody and control IgG, had to be administered on a daily basis to the rats. Large doses of IgG can ameliorate the course of immune-mediated renal disease, 31 and the therapeutic effect of IgG per se is variable from batch to batch (R. J. Johnson and J. Floege, personal observation). Second, mesangial cells express Fc-γ receptors and modulate their cytokine release on binding of IgG to Fc receptors. 10 These observations, in addition to the immunogenicity of heterologous antibodies, impose considerable restrictions on the interpretation of such studies.

At present, no other specific PDGF B-chain antagonists have been tested in vivo. Trapidil, an anti-platelet agent, has been shown to interfere with PDGF B-chain binding to mesangial PDGF receptors, but its action is not specific for PDGF. 32 Preliminary data suggest that a blocker of the PDGF receptor-associated tyrosine kinase may also ameliorate the course of mesangioproliferative nephritis, 33 but again, the compound was not specific for PDGF and also reduced, for example, basic-FGF-induced cell proliferation.

The possibility to develop aptamer antagonists for defined biological mediators has become an attractive novel therapeutic approach in various diseases. 23 These previous studies, in which thrombin, selectins, and neutrophil elastase were targeted, have demonstrated the ability of aptamers to act as antagonists of plasma or leukocyte proteins in vivo. 34-36 The present study is the first to demonstrate that specific antagonism of peptide growth factors, which are produced in a spatially much more confined manner, by high-affinity aptamers in vivo is not only feasible but also highly effective. In pilot studies the high effectiveness of the PDGF-B aptamer was also demonstrated in an experiment in which the injection of 5 mg of the aptamer at a single time point, ie, day 3 of the nephritis, was as efficient as several days of twice-daily treatment with a total of 10 to 30 mg (unpublished data). Furthermore, in pilot experiments we have observed that the effects of the PDGF-B aptamer in vivo are dose dependent and can be demonstrated with doses as low as 2 mg total. In support of our findings, the PDGF aptamer used in this study has recently exhibited efficacy in the rat model of restenosis (C.-H. Heldin and A. Östman, personal communication).

Apart from their specificity and potency, the use of aptamers largely circumvents problems of Fc receptor binding. Furthermore, although the effort to thoroughly examine the immunogenicity of aptamers is still in progress, extensive in vivo data obtained to date suggest that aptamers induce little if any immune response (J. Bill and G. Biesecker, unpublished results). Another attractive feature of aptamers is that their pharmacokinetic behavior can easily be altered, for example, by altering the molecular size (eg, via variation of the length of the attached PEG), hydrophobicity (eg, via packaging them in or on liposomes 9 ), or other features. A potential problem with the use of nucleic-acid-based antagonists is their polyanionic character, which might in itself affect the course of diseases. Thus, other polyanionic compounds, for example, heparins or heparan sulfate proteoglycans, are also effective in reducing mesangial cell proliferation in the anti-Thy-1.1 nephritis model. 14 However, in the present study, this concern was resolved by the ineffectiveness of a scrambled aptamer, which is identical in composition and predicted secondary structure to the PDGF-B aptamer but whose binding affinity for PDGF B-chain is dramatically lower.

In conclusion, we describe the efficacy of a high-affinity nucleic-acid-based growth factor antagonist in vivo and thereby extend the currently available evidence that PDGF B-chain is a central mediator in mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. The specificity and effectiveness demonstrated with the currently used aptamer opens the possibility for growth factor inhibition over prolonged periods. Aptamers may thus be used both to elucidate the role of individual growth factors that represent potential targets for therapeutic intervention and to serve as drug candidates for the treatment of disease states characterized by growth factor overexpression.

Acknowledgments

The technical help of Monika Kregeler, Astrid Fitter, and Yvonne Schönborn is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Jeff Walenta, Philippe Bridonneau, Girija Rajagopal, and Tim Romig for the synthesis and purification of aptamers. We also thank Nikos Pagratis and Dan Drolet for cloning of rat PDGF-BB and Joe Senello for providing rat serum for the aptamer stability studies.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Jürgen Floege, Division of Nephrology 6840, Medizinische Hochschule, 30623 Hannover, Germany (E-mail: Floege.Juergen@MH-Hannover.de) or Nebojsa Janjic, Ph.D.,

Supported by a grant (SFB 244/C12) and a Heisenberg stipend of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to J. Floege.

J. Floege and T. Ostendorf contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Tuerk C, Gold L: Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249:505-510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellington A, Szostak J: In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346:818-822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross R: Cell biology of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Physiol 1995, 57:791-804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Floege J, Johnson RJ: Multiple roles for platelet-derived growth factor in renal disease. Miner Electrolyte Metab 1995, 21:271-282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slomowitz LA, Klahr S, Schreiner GF, Ichikawa I: Progression of renal disease. N Engl J Med 1988, 319:1547-1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson RJ, Raines EW, Floege J, Yoshimura A, Pritzl P, Alpers C, Ross R: Inhibition of mesangial cell proliferation and matrix expansion in glomerulonephritis in the rat by antibody to platelet-derived growth factor. J Exp Med 1992, 175:1413-1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Floege J, Eng E, Young BA, Johnson RJ: Factors involved in the regulation of mesangial cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Kidney Int Suppl 1993, 39:S47-S54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green LS, Jellinek D, Jenison R, Östman A, Heldin CH, Janjić N: Inhibitory DNA ligands to platelet-derived growth factor B-chain. Biochemistry 1996, 35:14413-14424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willis MC, Collins BD, Zhang T, Green LS, Sebesta D, Bell C, Kellogg E, Gill SC, Magillanez A, Knauer S, Bendele RA, Gill PS, Janjić N: Liposome-anchored vascular endothelial growth factor aptamers. Bioconj Chem 1998, 9:573-582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radeke HH, Gessner JE, Uciechowski P, Magert HJ, Schmidt RE, Resch K: Intrinsic human glomerular mesangial cells can express receptors for IgG complexes (hFcγRIII-A) and the associated FcεRI γ-chain. J Immunol 1994, 153:1281-1292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floege J, Topley N, Hoppe J, Barrett TB, Resch K: Mitogenic effect of platelet-derived growth factor in human glomerular mesangial cells: modulation and/or suppression by inflammatory cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol 1991, 86:334-341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lonnemann G, Shapiro L, Engler Blum G, Muller GA, Koch KM, Dinarello CA: Cytokines in human renal interstitial fibrosis. I. Interleukin-1 is a paracrine growth factor for cultured fibrosis-derived kidney fibroblasts. Kidney Int 1995, 45:837-844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson RJ, Garcia RL, Pritzl P, Alpers CE: Platelets mediate glomerular cell proliferation in immune complex nephritis induced by anti-mesangial cell antibodies in the rat. Am J Pathol 1990, 136:369-374 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burg M, Ostendorf T, Mooney A, Koch KM, Floege J: Treatment of experimental mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with non-anticoagulant heparin: therapeutic efficacy and safety. Lab Invest 1997, 76:505-516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshimura A, Gordon K, Alpers CE, Floege J, Pritzl P, Ross R, Couser WG, Bowen-Pope DF, Johnson RJ: Demonstration of PDGF B-chain mRNA in glomeruli in mesangial proliferative nephritis by in situ hybridization. Kidney Int 1991, 40:470-476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kliem V, Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Yoshimura A, Couser WG, Koch KM, Floege J: Mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in 5/6-nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int 1996, 49:666-678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hugo C, Pichler R, Gordon K, Schmidt R, Amieva M, Couser WG, Furthmayr H, Johnson RJ: The cytoskeletal linking proteins, moesin and radixin, are upregulated by platelet-derived growth factor, but not basic fibroblast growth factor in experimental mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest 1996, 97:2499-2508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eitner F, Westerhuis R, Burg M, Weinhold B, Gröne HJ, Ostendorf T, Rüther U, Koch KM, Rees AJ, Floege J: Role of interleukin-6 in mediating mesangial cell proliferation and matrix production in vivo. Kidney Int 1997, 51:69-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pieken WA, Olsen DB, Benseler F, Aurup H, Eckstein F: Kinetic characterization of ribonuclease-resistant 2′-modified hammerhead ribozymes. Science 1991, 253:314-317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummins LL, Owens SR, Risen LM, Lesnik EA, Freier SM, McGee D, Guinosso CJ, Cook PD: Characterization of fully 2′-modified oligoribonucleotide hetero- and homoduplex hybridization and nuclease sensitivity. Nucleic Acids Res 1995, 23:2019-2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herren B, Weyer KA, Rouge M, Lötscher P, Pech M: Conservation in sequence and affinity of human and rodent PDGF ligands and receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1993, 1173:294-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindner V, Giachelli CM, Schwartz SM, Reidy MA: A subpopulation of smooth muscle cells in injured rat arteries expresses platelet-derived growth factor B-chain. Circ Res 1995, 76:951-957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold L, Polisky B, Uhlenbeck OC, Yarus M: Diversity of oligonucleotide functions. Annu Rev Biochem 1995, 64:763-797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson RJ, Iida H, Alpers CE, Majesky MW, Schwartz SM, Pritzl P, Gordon K, Gown AM: Expression of smooth muscle cell phenotype by rat mesangial cells in immune complex nephritis: alpha-smooth muscle actin is a marker of mesangial cell proliferation. J Clin Invest 1991, 87:847-858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canaan-Kühl S, Ostendorf T, Zander K, Koch KM, Floege J: C-natriuretic peptide inhibits mesangial cell proliferation and matrix accumulation in vivo. Kidney Int 1998, 53:1143-1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto T, Wilson CB: Quantitative and qualitative studies of antibody-induced mesangial cell damage in the rat. Kidney Int 1987, 32:514-525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hugo C, Shankland SJ, Bowen-Pope DF, Couser WG, Johnson RJ: Extraglomerular origin of the mesangial cell after injury. J Clin Invest 1997, 100:786-794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujinaka H, Yamamoto T, Takeya M, Feng L, Kawasaki K, Yaoita E, Kondo D, Wilson CB, Uchiyama M, Kihara I: Suppression of anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis by administration of anti-monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 antibody in WKY rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997, 8:1174-1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Border WA, Okuda S, Languino LR, Sporn MB, Ruoslahti E: Suppression of experimental glomerulonephritis by antiserum against transforming growth factor-β1. Nature 1990, 346:371-374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goppelt-Struebe M, Stroebel M: Synergistic induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by platelet-derived growth factor and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett 1995, 374:375-378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nangaku M, Pippin J, Richardson CA, Schulze M, Young BA, Alpers CE, Gordon KL, Johnson RJ, Couser WG: Beneficial effects of systemic immunoglobulin in experimental membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 1996, 50:2054-2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gesualdo L, DiPaolo S, Ranieri E, Schena FP: Trapidil inhibits human mesangial cells proliferation: effect on PDGF β-receptor binding and expression. Kidney Int 1994, 46:1002-1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yagi M, Kato S, Kobayashi Y, Kobayashi N, Iinuma N, Nagano N, Yamamoto T: Beneficial effects of a selective platelet-derived growth factor receptor autophosphorylation inhibitor on proliferative glomerulonephritis in the rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997, 8:488A [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffin LC, Tidmarsh GF, Bock LC, Toole JJ, Leung LLK: In vivo anticoagulant properties of a novel nucleotide-based thrombin inhibitor and demonstration of regional anticoagulation in extracorporeal circuits. Blood 1993, 81:3271-3276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hicke BJ, Watson SR, Koenig A, Lynott CK, Bargatze RF, Chang YF, Ringquist S, Moon-McDermott L, Jennings S, Fitzwater T, Han HL, Varki N, Albinana I, Willis MC, Varki A, Parma D: DNA aptamers block L-selectin function in vivo. J Clin Invest 1996, 98:2688-2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bless NM, Smith D, Charlton J, Czermak BJ, Schmal H, Friedl HP, Ward PA: Protective effects of an aptamer inhibitor of neutrophil elastase in lung inflammatory injury. Curr Biol 1997, 7:877-880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]