Abstract

Expression of protein kinase C (PKC) isoenzymes -α, -β, -δ, -ε, -γ, -ι, -λ, -μ, -θ, and -ζ, and of their common receptor for activated C-kinase (RACK)-1, was determined immunohistochemically using specific antibodies in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens of early prostatic adenocarcinomas (n = 23) obtained at radical prostatectomy. Expression of each isoenzyme by malignant tissues was compared with nonneoplastic prostate tissues removed at radical cystectomy (n = 10). The most significant findings were decreased PKC-β expression in early neoplasia when compared to benign epithelium (P < 0.0001), together with a reciprocal increase in expression of PKC-ε (P < 0.0001). Detectable levels of PKC-α and PKC-ζ were also significantly increased in the cancers (P = 0.045 and P = 0.015 respectively) but did not correlate with either PKC-β or PKC-ε for individual cases. Alterations in the levels of the four PKC isoenzymes occurred specifically and consistently during the genesis and progression of human prostate cancer. PKC-δ, -γ, and -θ were not expressed in the epithelium of either the benign prostates or the cancers. Levels of expression for PKC-λ, -ι, -μ, and RACK-1 were not significantly different between the benign and malignant groups. Although changes in PKC isoenzyme expression may assist in explaining an altered balance between proliferation and apoptosis, it is likely that changes in activity or concentrations of these isoenzymes exert important modulating influences on particular pathways regulating cellular homeostasis. The findings of this study raise an exciting possibility of novel therapeutic intervention to regulate homeostatic mechanisms controlling proliferation and/or apoptosis, including expression of the p170 drug-resistance glycoprotein, intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, and enhanced cellular mobility resulting in the metastatic dissemination of human prostate cancer cells. Attenuation of PKC-β expression is currently being assessed as a reliable objective adjunct to morphological appearance for the diagnosis of early progressive neoplasia in human prostatic tissues.

Protein kinase C (PKC) comprises a family of at least 12 distinct serine/threonine kinase isoenzymes that have important actions in transmembrane signal transduction pathways and have been reported to regulate cell proliferation, 1 differentiation, 2 cell-to-cell interaction, 3 secretion, 4 cytoskeletal functions, 5 gene transcription, 6 apoptosis, 7 and drug resistance. 8 The family of isoenzymes is conventionally subdivided into three main categories (classic, novel, and atypical) according to cofactor requirements. Classic PKCs (-α, -β1, -β2, and -γ) and novel PKCs (-δ, -ε, -η, and -θ) can be activated in vivo by the second messenger diacylglycerol generated by receptor-ligand binding and in vitro by phorbol esters. Classic PKC isoenzymes are also dependent on calcium. In contrast, atypical PKCs (-ζ, -λ, -μ, -ι) are calcium-independent and are not activated by phorbol esters. 8

Members of the PKC family of isoenzymes, initially located in distinct subcellular compartments, are critical regulators of intracellular homeostasis, and thus intracellular communication and trafficking of a variety of protein and peptide molecules, through their interaction with anchoring proteins called receptors for activated C-kinase (RACKs) at specific sites. 9 Following translocation from the cytosol to cell membranes, activated PKCs form complexes with specific anchoring proteins, 10 phosphatidylserine and a range of cytoactive proteins including the p170 drug-resistance glycoprotein. Each PKC isoenzyme is characterized by its particular ability to phosphorylate a spectrum of intracellular proteins including P-glycoprotein raf kinase and (at least with respect to PKC-α within the family of PKC proteins) to autophosphorylate. The suggestion that different PKC isoenzymes have defined intracellular functions is supported by their distinct subcellular locations, 11 substrate specificities, 12 requirements for activation, 12,13 and rates of down-regulation. 14 Thus, the potential exists for specific inhibitors to modulate or to prevent particular isoenzyme-specific functions of PKC in complex signal transduction pathways.

Although central in regulating critical homeostatic pathways, the PKC family of isoenzymes has been proposed to have an important role in carcinogenesis. The enzymes have been implicated in metastasis 15 and chemotherapy-associated multidrug resistance. 16 Total PKC activity has been reported to be increased in carcinomas of breast 17 and lung 18 and reduced in colon adenocarcinoma. 19 Interest in the role of PKC in prostate cancer was stimulated when it was shown that PKC activity was vital for the growth of androgen-independent prostate cells 20 whereas in androgen-sensitive cell lines, PKC activity causes apoptosis. 21 Powell et al 22 suggested that activation of PKC-α occurs at a critical point in the apoptosis pathway in the androgen-sensitive LNCaP cell line, and that lack of PKC-α may explain resistance of androgen-independent PC-3 and Du-145 prostate cancer cell lines to apoptosis. Conversely, Lamm et al 23 demonstrated that reduction in PKC-α causes growth impairment in PC-3 cells and Liu et al 24 showed that activation of PKC-α is associated with increased invasiveness in Dunning (AT2.1 rat prostate) adenocarcinoma cells. In human prostate cancer cell lines, it has been suggested that specific down-regulation of PKC-ε prevents apoptosis 25 and that PKC-ζ overexpression decreases invasive and metastatic potential. 26

Our hypothesis, based on recent information gathered from this laboratory 27-29 and elsewhere (Abd-Elghany MI, Bashir I, Cornford P, Dodson AR, Brawn P, Thomas C, Ke Y, Foster CS, unpublished manuscript; Bashir I, Abd-Elghanay M, Dodson AR, Sikora K, Foster CS, unpublished manuscript), is that during prostatic oncogenesis there is a loss or down-regulation of specific intracellular homeostatic mechanisms likely to involve particular isoenzymes within the PKC family. To test this hypothesis, we now describe a comprehensive analysis of the expression of the currently known spectrum of PKC isoenzymes together with receptor protein RACK-1 in human prostatic carcinomas and in benign prostatic control tissues. No previous expression of PKC isoenzymes has been reported in either human normal prostatic tissue or in untreated primary prostatic adenocarcinomas. Failure of such homeostatic mechanisms results in diminished anion transport, altered intracellular cation concentration, and impaired maintenance of cell volume through PKC regulation of members of the ATP-binding cassette superfamily of molecular transporters. 30,31 In recognition of the critical role of stromal-epithelial interactions in the morphogenesis and maintenance of normal prostatic tissues as well as in the behavioral phenotypes that emerge from within individual prostate cancers, an assessment is also made of PKC isoenzyme distribution in prostatic stromal tissues and the epithelial compartment. The findings of this study reveal, for the first time, a strong association between changes in levels of specific PKC isoenzymes and both the genesis and the progression of human prostate cancers.

Materials and Methods

Tissues Examined

Controls

Positive control tissues for each of the PKC isoenzyme antibodies were chosen following the supplier’s recommendations as summarized in Table 1 ▶ .

Table 1.

Dilution, Pre-treatment, and Positive Controls for the Primary Antibodies

| Isoenzyme | Dilution | Pre-treatment | Positive Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| PKC-α | 1 /200 | None | Bone marrow |

| PKC-β | 1 /50 | MW | Tonsil |

| PKC-δ | 1 /50 | None | Smooth muscle |

| PKC-ε | 1 /50 | MW | Colon |

| PKC-γ | 1 /400 | None | Adrenal |

| PKC-λ | 1 /100 | MW | Colon |

| PKC-ι | 1 /8000 | MW | Brain |

| PKC-θ | 1 /100 | MW | Bone marrow |

| PKC-μ | 1 /800 | MW | Colon |

| PKC-ζ | 1 /800 | MW | Brain |

| RACK-1 | 1 /800 | MW | Brain |

MW, microwave.

Benign Prostatic Tissues

Tissues were examined from 10 prostates removed from men (average age 52.4 years) undergoing primary cysto-prostatectomy for invasive transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder. All tissue samples were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Pathology, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool, UK. All specimens were reviewed to confirm that there was no incidental prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) or carcinoma in the control samples. However, all 10 patients with bladder TCC had received standard intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy before their radical surgery. For each specimen, a complete hemisection of the prostate gland was examined from the level of the verumontanum.

Prostatic Carcinomas

Tissues from 23 consecutive, previously untreated patients with a diagnosis of organ-confined prostate cancer were examined. Primary diagnosis was made on core needle biopsy and the possibility of spread investigated by bone scan, CT, and transrectal ultrasound scanning (TRUS). (Since 1995, TRUS has been superseded by transrectal magnetic resonance imaging.) Mean preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was 10.2 μg/ml (range 2.5–25 μg/ml). Patients underwent radical retropubic prostatectomy between 1990 and 1996. Their average age was 55.4 years (range, 49.7–68.5 years) and the mean follow-up was 44 months (range, 17–92 months). At the time of follow-up, one patient had died of recurrent prostatic carcinoma 37 months after surgery and one patient had clinical evidence of recurrent tumor at 19 months after surgery. Another patient had an elevated serum PSA (7.2 μg/l) that began to rise at 33 months after surgery and was considered to have chemical evidence of recurrence. Two other patients had died of unrelated causes. Gleason grading of all prostatic carcinomas included in this study was performed by two pathologists according to conventional criteria. 32

Antibodies and Antisera

Monoclonal antibodies to PKC isoenzymes and to receptor protein RACK-1 were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). In addition, a polyclonal antibody to PKC-α was purchased from GIBCO (Life Technologies Ltd., Paisley, UK). Monoclonal antibodies to PKC isoenzymes -α, -δ, and -γ required no pretreatment. The polyclonal antibody to PKC-α and monoclonal antibodies to PKC isoenzymes -β, -ε, -ι, -μ, -λ, -θ, -ζ and to RACK-1 required microwave pretreatment for antigen retrieval. Microwave exposure was performed at 850 Watts for 15 minutes in 10 mmol/L ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid solution (pH 7.0), after which slides were allowed to cool in the same solution at room temperature for 15 minutes. Antibodies were diluted in Tris-buffered saline containing 5% bovine serum albumin to the concentrations shown in Table 1 ▶ .

Immunohistochemistry

Sections of each specimen 4 μm thick were prepared on poly-L-lysine coated glass slides. Sections were deparaffinized by two consecutive treatments with xylene and rehydrated by sequential immersion in graded alcohol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by treatment with a 3% solution of hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 minutes. Sections were then rinsed in tap water followed by distilled water before being submitted to microwave antigen retrieval. After washing in fresh Tris-buffered saline (0.05 mol/L Tris; 0.12 mol/L NaCl, pH 7.6), slides were incubated with the primary antibodies for 60 minutes at room temperature. Sections were then washed twice with Tris-buffered saline before biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin applied for 45 minutes at room temperature. Biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin were purchased from Amersham Life Science (Little Chalfont, UK). Thereafter, sections were washed twice before application of horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin-biotin complex (Dako Ltd., High Wycombe, UK) for 30 minutes at room temperature. After further washing, sections were immersed in 3,3′ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Dako Ltd.) diluted to 250μg/ml in 0.03% hydrogen peroxide for 7 minutes to reveal sites of bound antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin before mounting slides in DPX Mountant. For the two negative controls used in each experiment, either the primary or the secondary antibody was replaced with 5% bovine serum albumin. All sections were independently scored by two investigators (CSF and PAC).

Analysis of PKC Expression

Specimens were considered positive only when at least 5% of the contained epithelial cells (either normal or malignant) unequivocally expressed PKC isoenzyme staining. 33 This cutoff has been previously used as the criterion to distinguish positive from negative immunohistochemical staining of prostatic epithelium. 34 For each tissue section staining was assessed as negative, weakly or only focally positive (low-level), or strongly positive (high-level) and scored as 0, 1, or 2, respectively. For each of the positive sections, assessments were made of the cellular distribution of each PKC isoenzyme in benign, malignant or metastatic human prostatic epithelium and of the relationship between expression of PKC isoenzyme and tumor grade. All data were recorded electronically and analyzed using the StatView (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA) statistical package.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical values of significance were determined using the χ2 test throughout, with Yates’ correction used for those data comprising small numbers. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

All PKC isoenzymes examined were found to exhibit consistent patterns of distribution within both benign and malignant prostatic tissues. Within the control “normal” benign prostatic tissues, no differences were found between hyperplastic and non-hyperplastic areas. No isoenzyme was found which was not expressed in characteristic locations within those tissues.

Isoenzymes Expressed by Stroma but not by Epithelium: PKC-δ and PKC-γ

Within the stroma, PKC-δ was expressed by smooth muscle cells and by dendritic reticulum cells while PKC-γ was expressed by nerve cells and their ganglia in both benign and malignant tissues. PKC isoenzymes -δ and -γ were not expressed by either benign or malignant prostatic epithelium in any of the cases examined (Table 2) ▶ . These characteristically-consistent cellular distributions acted as additional internal positive controls for staining with these two antibodies.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemistry Results on 23 Radical Prostatectomy Specimens and 10 Age-matched Controls

| Antibody to | Stroma | Epithelium | p* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Weak | Strong | Negative | Weak | Strong | ||

| PKC-α | |||||||

| Ca | 2 | 14 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 13 | p = 0.045 |

| Control | 0 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 | |

| PKC-β | |||||||

| Ca | 7 | 14 | 2 | 12 | 8 | 3 | p < 0.0001 |

| Control | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| PKC-δ | |||||||

| Ca | 0 | 0 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 0 | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| PKC-ε | |||||||

| Ca | 23 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 9 | p < 0.0001 |

| Control | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| PKC-γ | |||||||

| Ca | 4 | 8 | 11 | 23 | 0 | 0 | |

| Control | 4 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| PKC-ι | |||||||

| Ca | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 12 | |

| Control | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | |

| PKC-λ | |||||||

| Ca | 23 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 11 | p = 0.059 |

| Control | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 | |

| PKC-μ | |||||||

| Ca | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20 | |

| Control | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | |

| PKC-θ | |||||||

| Ca | 23 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 3 | 0 | |

| Control | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| PKC-ζ | |||||||

| Ca | 0 | 6 | 17 | 0 | 3 | 20 | p = 0.015 |

| Control | 0 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| RACK-1 | |||||||

| Ca | 23 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 6 | |

| Control | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 1 |

*Statistical significance of epithelial immunoreactivity, χ2 test.

Isoenzymes Expressed by Epithelium but not by Stroma: PKC-ι, PKC-μ, PKC-θ, and RACK-1

PKC-ι and PKC-μ were widely expressed by both benign and malignant epithelia in all cases (Table 2) ▶ , with no apparently qualitative difference in their expression between the two types of tissues. PKC-μ appeared as punctate staining within the cytoplasm of all epithelial cells suggesting that this isoenzyme was distributed to a subcellular compartment such as the endoplasmic reticulum. PKC-θ was weakly expressed by invasive cells in three cases of prostate cancer, but no expression of this isoenzyme was found in any benign epithelium. Staining with the anti-RACK-1 antibody did not discriminate between benign and malignant tissues. RACK-1 was expressed in 70% of controls and 70% of cancers (Table 2) ▶ . No staining of any stromal components was identified in any of the benign or malignant cases examined using the antibodies to these four proteins.

Isoenzymes Expressed Differently by Benign and Malignant Epithelia: PKC-α, PKC-β, PKC-ε, PKC-λ, and PKC-ζ

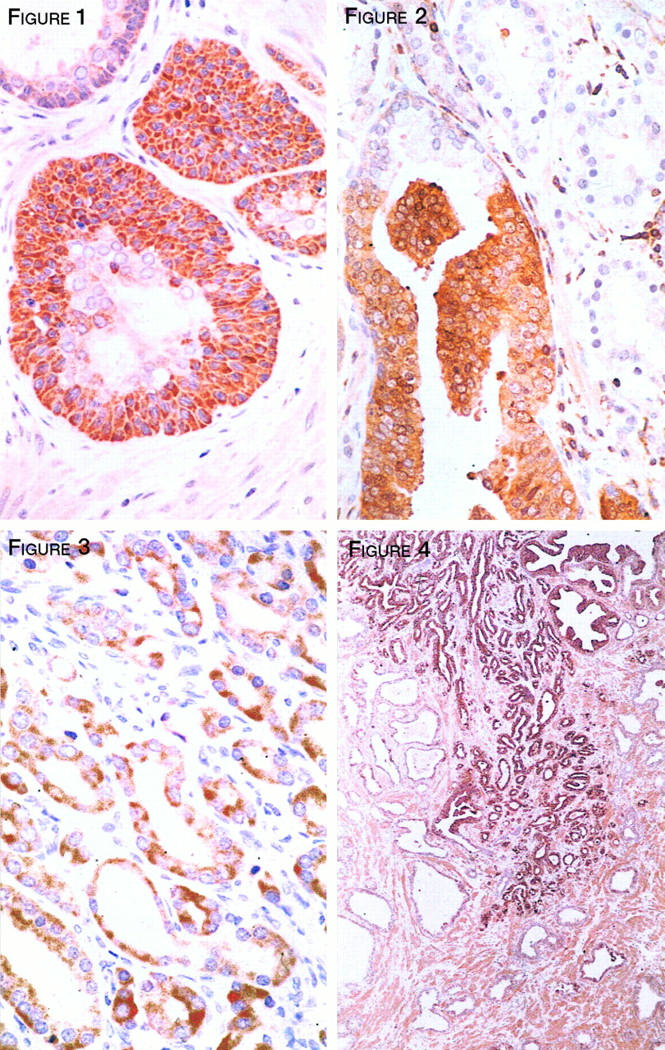

PKC-α was not identified in histological sections of either benign or malignant tissues using the monoclonal antibody from Transduction Laboratories, despite exhaustive attempts to adjust pretreatment antigen retrieval or antibody dilution. However, as revealed by the polyclonal antibody (Gibco) this isoenzyme occurred almost ubiquitously throughout the tissues. While the qualitative level of expression was statistically increased in the group of early cancers (P < 0.05), its quantitative expression with respect to the number of tissues stained was not statistically different (Figure 1) ▶ .

Figure 1.

PKC-α staining of prostatic basal cell hyperplasia with focal dysplastic features. The neoplastic basal cells express a significantly enhanced level of staining when compared to the overlying luminal cells or to adjacent nonneoplastic epithelium. Magnification, ×360.

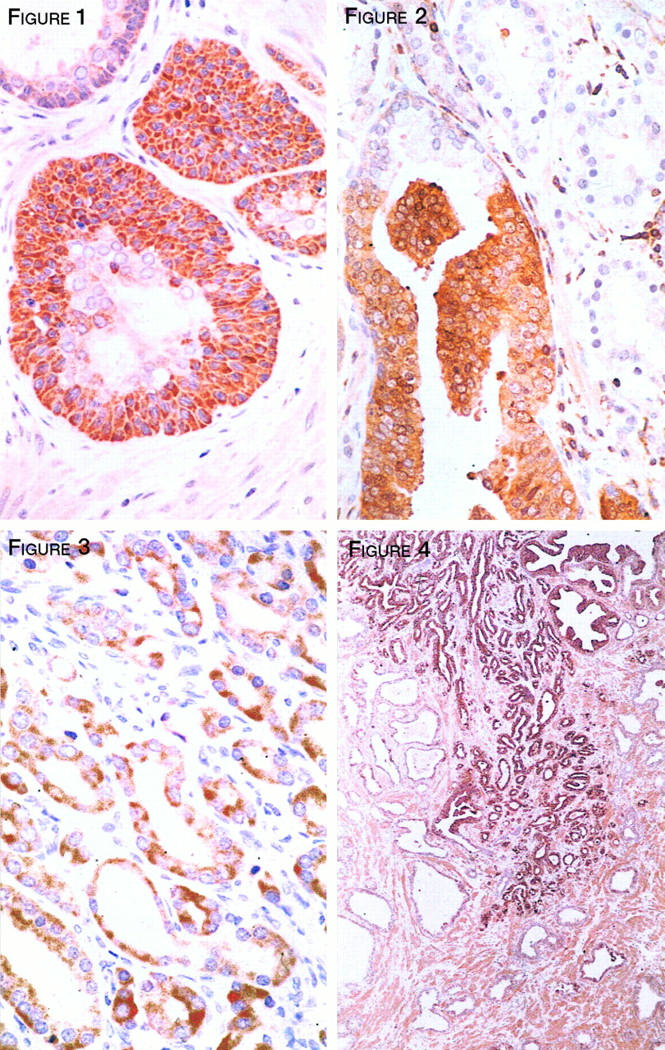

PKC-β was strongly and uniformly expressed throughout the epithelium of all 10 control samples and in a similar pattern by all benign epithelium adjacent to the cancers. This isoenzyme was strongly expressed by malignant epithelium in only three cancers although an additional eight samples showed some weak expression. Malignant epithelia of 12 cases failed to express this PKC isoform (Figure 2) ▶ . In the cancers which did stain, the pattern was heterogeneous and restricted to small focal regions of the tumors. When compared to nonneoplastic prostatic epithelium, prostate cancers showed a significant reduction in expression of PKC-β (P < 0.0001). No correlation was found between PKC-β expression and Gleason grade. Those patients whose tumors expressed PKC-β were at significantly greater risk of recurrence (0/14 versus 4/9 P < 0.01 < P < 0.05) (mean follow-up 44 months; range, 17–92 months). In five cases where high grade PIN was also present, this was negative for PKC-β, suggesting that this isoenzyme may be down-regulated at an early stage in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer.

Figure 2.

PKC-β expression by residual nonneoplastic epithelial cells within a terminal duct. However, adjacent and well-differentiated invasive prostate cancer cells do not express this isoenzyme. Similarly, foci of adjacent in situ neoplastic epithelial cells are negative, thus demonstrating the loss of this isoenzyme in early prostatic neoplasia. Magnification, ×360.

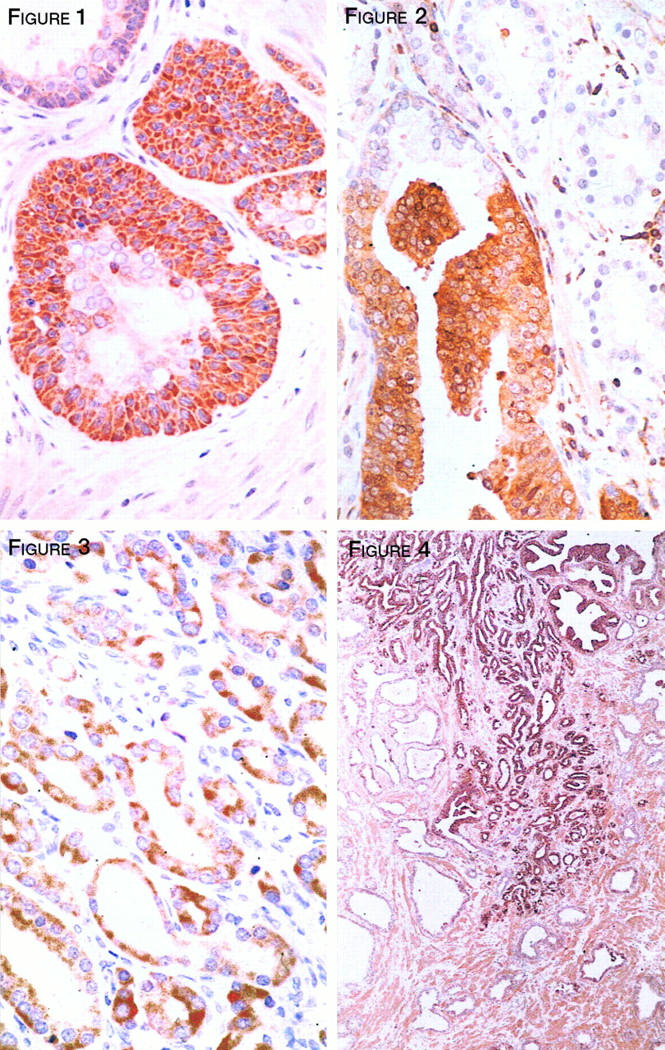

Although PKC-ε was not expressed by any benign epithelia (Table 2) ▶ , it was expressed in 22 of 23 (96%) samples of prostate cancer (Figure 3) ▶ . Statistical analysis confirmed this increase in expression to be highly significant (P < 0.0001). No relationship was identified between PKC-ε expression and Gleason grade of the examined tumors. In five cases where high grade PIN was identified, increased staining was also found in adjacent foci of epithelial dysplasia, suggesting this to be a specific change occurring early in prostatic neoplasia. χ2 analysis confirmed an inverse relationship between PKC-β and PKC-ε expression (0.0001 < P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

PKC-ε strongly expressed by moderately differentiated, invasive prostate cancer cells. Stromal expression of this isoenzyme is not identified in these invasive neoplasms. Magnification, ×360.

Although there was a trend suggesting increased expression of PKC-λ, it failed to reach statistical significance (0.05 < P < 0.10).

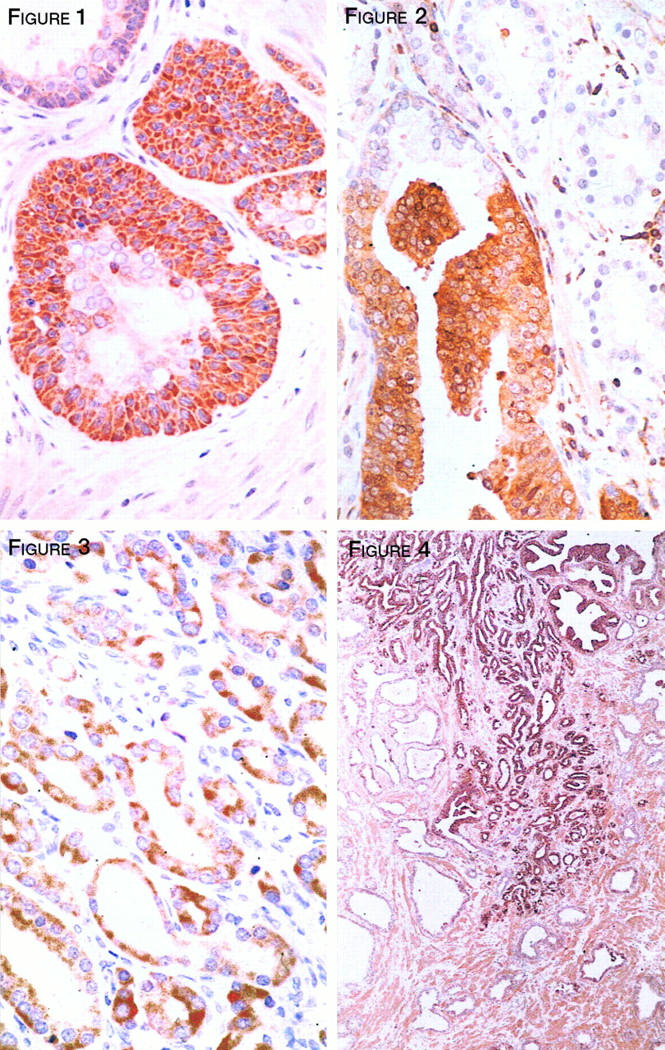

Expression of PKC-ζ was statistically increased in the cancers (0.01 < P < 0.05) compared to control benign tissues (Figure 4) ▶ .

Figure 4.

Enhanced expression of PKC-ζ by early invasive prostate cancer infiltrating between nonneoplastic glands. Foci of high grade PIN are also strongly positive. Smooth muscle cells within the stroma characteristically express this isoenzyme. Magnification, ×50.

Discussion

This study has revealed the normal profile of PKC isoenzyme expression within the epithelia and the stroma of human benign prostatic tissues to be specifically and consistently modulated in early-stage prostate cancers. When compared to the benign tissues, PKC-β expression was dramatically reduced in neoplastic epithelia (Figure 2) ▶ . Loss of PKC-β expression appeared to be a relatively early event in prostate cancer and was undetectable in foci of PIN contained within five different cases in this study. Previously, PKC-β has been shown to be decreased in other solid tumors including colon carcinoma 19,35 and pancreatic neoplasia. 36 It has also been suggested that loss of PKC-β may decrease the rate of apoptosis in prostatic adenocarcinoma. In tissue culture, this particular isoenzyme appears necessary for phorbol ester-induced apoptosis of HL-60 promyelocytes 37 and HT29 colon cancer cells. 37,38 Furthermore, expression of PKC-β1 is also considered to cause anchorage-independence 39 and hence may permit metastatic development. This finding may explain the observation that tumors continuing to express PKC-β had a worse outcome.

PKC-ε was found to be reciprocally increased in the cancer cells when compared to PKC-β (Figure 3) ▶ . This isoenzyme is thought to enhance proliferation 40 and has been reported to act as an oncoprotein in rat fibroblasts via activation of raf kinase. 41 A similar mechanism may also occur early in prostatic neoplasia because foci of PIN included in the samples stained strongly for PKC-ε, whereas no expression was detected in any of the benign tissues. After PKC-ε is stimulated intracellularly by diacylglycerol derived from phosphatidyl choline it activates proto-oncogene c-Raf-1. 42 Interaction between its zinc finger domain and a specific epitope on Ras-GTP 43 results in recruitment of Raf to the plasma membrane, where it becomes an integral part of the signal cascade initiated by activated growth factor receptors (particularly EGFr) and transduced via Ras guanine nucleotide-binding proteins. However, at least in some epithelial cell types PKC-α can act downstream of PKC-ε by directly stimulating Raf, suggesting that these diacylglycerol-regulated PKCs function as redundant activators of Raf-1 in vivo. Currently available data indicate that in the majority of human prostate neoplasms, mutations of Ras and Raf are rare and do not contribute to the spectrum of common pathogenetic mechanisms resulting in prostate cancer. 44,45 In the present study, PKC-ε was not identified in either the epithelial or stromal compartments of benign prostatic tissues or in the stroma of prostate cancers. However, neoexpression of this isoenzyme was identified in 22 of the 23 (96%) cases of prostate cancer. There was no relationship between PKC-ε expression and either primary or secondary Gleason grade. When the prostate cancers expressing PKC-α and those expressing PKC-ε were compared, a trend suggesting reciprocity of expression was obtained for all tissues (P = 0.067). These findings suggest that, because of inherent redundancy in the signalling pathway, the capacity for alternative stimulation, and the absence of information identifying mutations or other defects in the system, it is likely that the Ras→Raf cascade is fully activated by at least one of two distinct PKC isoenzymes (either -α or -ε) in all human prostate cancers.

PKC-ι was expressed within the epithelium of all benign and malignant prostatic specimens examined. With respect to the cancers, this is particularly significant because PKC-ι has been shown to protect other types of neoplastic cells to form drug-induced apoptosis, 46 rather than affecting pathways regulating cellular differentiation or proliferation. Significantly, rates of apoptosis in benign and malignant prostatic epithelium are usually very low. 47,48 Characteristically, these cells are sensitive to drug-induced cytotoxic agents, including those that induce apoptosis, because they do not express the p170 multidrug-resistance glycoprotein, (Abd-Elghany MI, Bashir I, Cornford P, Dodson AR, Brawn P, Thomas C, Ke Y, Foster CS, unpublished manuscript) at least until exposure to chemotherapeutic agents or other appropriate stimuli.

In summary, this study has demonstrated that specific and consistent alterations in expression of PKC isoenzymes are associated with the development and possibly the progression of prostatic adenocarcinoma by impairing intracellular homeostatic mechanisms. Altered regulation of at least some of these isoenzymes is also thought to promote tumor dissemination by disabling cell adhesion mechanisms and inhibiting apoptosis. The finding that intracellular localization and function of individual PKC isoenzymes may be perturbed by peptides that interfere with or promote specific intracellular protein-protein interactions provides an opportunity for devising novel therapeutic techniques to manipulate these pathways of intracellular homeostatic regulation, thus modulating the phenotypic behavior of tumor cells in different environments. The family of PKC isoenzymes contains at least one potential target by which tumor growth may be modified and which may be particularly important in chemoresistant cancers of the classical multidrug resistance phenotype. Although precise intracellular mechanisms and pathways in which the PKC family of protein kinases are involved have not yet been fully elucidated, the current study has clearly shown that detectable levels (and probably also activities) of particular isoenzymes are specifically and consistently modulated in prostatic carcinomas when compared to nonmalignant prostatic epithelial cells. Attenuation of PKC-β expression is currently being assessed as a reliable prognostic marker of progressive neoplasia in the diagnosis of early prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Alan Williams for photographic assistance, Mrs. Jill Gosney for typing and editing the manuscript, and Mrs. Norma Carter for validating the survival data.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Mr. P.A. Cornford, Department of Surgery, University of Liverpool, P.O. Box 147, Liverpool L69 3GA, UK.

Supported by Kancatak (Carbofab) Research Ltd., Stanley Thomas Johnson Memorial Foundation, Prostate Cancer Cure Foundation, and a BMA Insole Award. P.A.C. is current holder of the Insole Award. Generous funding for this project was obtained, in part, from the Stanley Thomas Johnson Memorial Foundation, Switzerland from Kancatak (Carbofab Research Ltd.) and from the Prostate Cancer Cure Foundation.

References

- 1.Lord JM, Pongracz J: Protein kinase C: a family of isoenzymes with distinct roles in pathogenesis. Clin Mol Pathol 1995, 48:57-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemens MJ, Trayner I, Meneya J: The role of protein kinase C isoenzymes in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Sci 1992, 103:881-887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freed E: A novel intergrin β subunit is associated with the vitronectin receptor α-subunit (α-v) in a human osteosarcoma cell line and is a substrate for protein kinase C. EMBO J 1989, 8:2955-2965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lord JM, Ashcroft SJH: Identification and characterisation of Ca2+- phospholipid-dependent protein kinase in rat islets and hamster β cells. Biochem J 1984, 219:547-551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owen PJ, Johnson GD, Lord JM: Protein kinase C-delta associates with vimentin intermediate filaments in differentiated HL-60 cells. Exp Cell Res 1996, 225:366-373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry N, Nishizuka Y: Protein kinase C and T cell activation. European Journal of Biochemistry 1990, 189:205-214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pongracz J, Johnson GD, Crocker J, Burnett D, Lord JM: The role of protein kinase C in myeloid cell apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans 1994, 22:593-597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dekker LV, Parker PJ: Protein kinase C: a question of specificity. Trends in Biochemical Science 1994, 19:73-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mochley-Rosen D, Gordon AS: Anchoring proteins for protein kinase C: a means for isozyme selectivity. FASEB J 1998, 12:35-42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mochley-Rosen D, Khaner H, Lopez J: Identification of intracellular receptor proteins for activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991, 88:3997-4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leach KL, Powers EA, Ruff VA, Jaken S, Kaufmann S: Type 3 protein kinase C localisation to the nuclear envelope of the phorbol ester treated NIH-3T3 cells. J Cell Biol 1989, 109:685-695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang KP, Huang FL, Nakabayashi H, Yoshida Y: Biochemical characterisation of rat brain protein kinase C isoenzymes. J Biol Chem 1988, 263:14839-14845 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaken S, Kiley SC: Purification and characterisation of 3 types of protein kinase C from rabbit brain cytosol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987, 84:4418-4422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiley SC, Schaap D, Parker P, Hsieh LL, Jaken S: Protein kinase C heterogeneity in GH4C1 rat pituitary cells. J Biol Chem 1990, 265:15704-15712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbert JM: Protein kinase C: a key factor in the regulation of tumor cell adhesion to the endothelium. Biochem Pharmacol 1993, 45:527-537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blobe GC, Sachs CW, Khan WA, Fabbro D, Stabel S, Westal WC, Obeid LM, Fine RL, Hannun YA: Selective regulation of expression of protein kinase C (PKC) isoenzyme in multidrug resistant MCF-7 cells-functional significance of enhanced expression of PKC-α. J Biol Chem 1993, 268:658-664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brian CA, Vogel VG, Singletary SE, Ward NE: Elevated protein kinase C expression in human breast tumor biopsies relative to normal breast tissue. Cancer Res 1989, 49:3215-3217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirai M, Gamou S, Kobayashi M, Shimizu N: Lung cancer cells often express high levels of protein kinase C activity. Japanese J Cancer Res 1989, 80:204-208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pongracz J, Clark P, Neoptolemos JP, Lord JM: Expression of protein kinase C isoenzymes in colorectal cancer tissue and their differential activation by different bile acids. Int J Cancer 1995, 61:35-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krongrad A, Bai G: c-fos promoter insensitivity to phorbol ester and possible role of protein kinase C in androgen-independent cancer cells. Cancer Res 1994, 54:203-210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young CY, Murtha PE, Zhang J: Tumor promoting phorbol ester-induced cell death and gene expression in a human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line. Oncol Res 1994, 6:203-210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell CT, Brittis NJ, Stec D, Hug H, Heston WD, Fair WR: Persistent membrane translocation of protein kinase C α during 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced apoptosis of LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ 1996, 7:419-428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamm ML, Long DD, Goodwin SM, Lee C: Transforming growth factor β 1 inhibits membrane association of protein kinase C α in a human prostate cancer cell line, PC3. Endocrinology 1997, 138:4657-4664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B, Maher RJ, Hanun YA, Porter AT, Honn KV: 12(S)-HETE enhancement of prostate tumor cell invasion: selective role of PKC α. J Natl Can Inst 1994, 86:1145-1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rusnak JM, Lazo JS: Downregulation of protein kinase C suppresses induction of apoptosis in human prostatic carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res 1996, 224:189-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell CT, Gschwend JE, Fair WR, Brittis NJ, Stec D, Huryk R: Overexpression of protein kinase C-zeta (PKC-zeta) inhibits invasive and metastatic abilities of Dunning R-3327 MAT-LyLu rat prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 1996, 56:4137-4141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bashir I, Sikora K, Foster CS: Multidrug resistance and behavioral phenotype of cancer cells. Cell Biol Int 1993, 17:907-917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ke Y, Jing C, Barraclough R, Smith P, Davies MPA, Foster CS: Elevated expression of calcium-binding protein p9Ka is associated with increasing malignant characteristics of rat prostate carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer 1997, 71:832-837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith P, Rhodes NP, Shortland AP, Fraser SP, Djamgoz MBA, Ke Y, Foster CS: Sodium channel protein expression enhances the invasiveness of rat and human prostate cancer cells. FEBS Lett 1998, 423:19-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyde SC, Emsley P, Hartshorn MJ, Mimmack MM, Gileadi U, Pearce SR, Gallagher MP, Gill DR, Hubbard RE, Higgins CF: Structural model of ATP-binding proteins associated with cystic fibrosis, multidrug resistance and bacterial transport. Nature 1990, 346:362-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miwa A, Ueda K, Okada Y: Protein kinase C-independent correlation between P-glycoprotein expression and volume sensitivity of Cl-channel. J Membr Biol 1997, 157:63-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deshmukh N, Foster CS: Grading prostate cancer. Foster CS Bostwick DG eds. Pathology of the Prostate. 1997, :pp 191-227 WB Saunders, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Diest P, van Dam P, Henzen-Logman SC: A scoring system for immunohistochemical staining: consensus report of the task force for basic research of the EORTC-GICCG. J Clin Pathol 1997, 50:801-804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharpe JC, Abel PD, Gilbertson JA, Brawn P, Foster CS: Modulated expression of human leucocyte antigen class I and class II determinants in hyperplastic and malignant human prostatic epithelium. Br J Urol 1994, 74:609-616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy MF, Pocsidio J, Guillem JG, Forde K, Logerfo P, Weinstein IB: Decreased levels of protein kinase C enzyme activity and protein kinase C mRNA in primary colon tumors. Dis Colon Rectum 1993, 36:913-921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gleason D: Histologic grading and clinical staging of carcinoma of the prostate, in Urologic Pathology. The Prostate. Edited by Tannenbaum M. Philadelphia PA, Lea and Febiger, 1977, pp 171–197

- 37.MacFarlane DE, Manzel L: Activation of Beta-isoenzyme of protein kinase C (PKC β) is necessary and sufficient for phorbol ester-induced differentiation of HL60 promyelocytes. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:4327-4331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi PM, Weinstein B: The modulation of growth by HMBA in PKC overproducing HT29 colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 1991, 181:809-817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borner C, Ueffing M, Jaken S, Parker PJ, Weinstein BI: Two closely related isoforms of protein kinase C produce reciprocal effects on the growth of rat fibroblasts. Possible molecular mechanisms. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:78-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perletti GP, Folini M, Lin HC, Mischak H, Piccinini F, Tashjian AHJ: Overexpression of protein kinase C epsilon is oncogenic in rat colonic epithelial cells. Oncogene 1996, 12:847-854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cacace AM, Guadagno SN, Krauss RS, Fabbro D, Weinstein IB: The epsilon isoform of protein kinase C is an oncogene when overexpressed in rat fibroblasts. Oncogene 1993, 8:2095-2104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cai H, Smola U, Wixler V, Eisenmann-Tappe I, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J, Rapp U, Cooper GM: Role of diacylglycerol-regulated protein kinase C isotypes in growth factor activation of the Raf-1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17:732-741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo Z, Diaz B, Marshall MS, Avruch J: An intact Raf zinc finger is required for optimal binding to processedRas and for ras-dependent Raf activation in situ. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17:46-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foster CS, McLoughlin J, Bashir I, Abel PD: Markers of the metastatic phenotype in prostate cancer. Hum Pathol 1992, 23:381-394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foster CS, Cornford P, Forsyth L, Djamgoz MBA, Ke Y: The cellular and molecular basis of prostate cancer. Br J Urol 1999, In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Murray NR, Fields AP: Atypical protein kinase C iota protects human leukemia cells against drug-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:27521-27524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kyprianou N, Tu H, Jacobs SC: Apoptotic versus proliferative activities in human benign prostatic hyperplasia. Hum Pathol 1996, 27:668-675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tu H, Jacobs SC, Borkowski A, Kyprianou N: Incidence of apoptosis and cell proliferation in prostate cancer: relationship with TGF-β1 and bcl-2 expression. Int J Cancer 1996, 69:357-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]