Abstract

The Tuskegee Institute opened a polio center in 1941, funded by the March of Dimes. The center’s founding was the result of a new visibility of Black polio survivors and the growing political embarrassment around the policy of the Georgia Warm Springs polio rehabilitation center, which Franklin Roosevelt had founded in the 1920s before he became president and which had maintained a Whites-only policy of admission. This policy, reflecting the ubiquitous norm of race-segregated health facilities of the era, was also sustained by a persuasive scientific argument about polio itself: that Blacks were not susceptible to the disease.

After a decade of civil rights activism, this notion of polio as a White disease was challenged, and Black health professionals, emboldened by a new integrationist epidemiology, demanded that in polio, as in American medicine at large, health care should be provided regardless of race, color, or creed.

IN MAY 1939, BASIL O’CONNOR, director of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, announced that the foundation would provide $161350, its largest single grant, to build and staff a polio center at the Tuskegee Institute. The Tuskegee Infantile Paralysis Center, O’Connor claimed, would “provide the most modern treatment for colored infantile paralysis victims” and would “train Negro doctors and surgeons for orthopedic work,” as well as orthopedic nurses and physical therapists.1 Designing the center as a site for both health care and professional training was intended to compensate for the many hospitals in Alabama and across the region that refused to treat Black patients or accept Black providers on their staff. Orthopedic care at the Tuskegee Center, O’Connor boasted, would help “hundreds of children who might otherwise be doomed to a lifetime of crippling.”2 Yet from the outset, the center, with only 36 beds and limited outpatient facilities, could help only a fraction of the patients who sought its care. Implicit in O’Connor’s remarks, then, was an acknowledgment of what physician W. Montague Cobb would excoriate a few years later as the enduring “Negro medical ghetto.”3

The center opened with much fanfare in January 1941, marked by a ceremony broadcast nationally on the radio. In a special message read at the event by O’Connor, President Franklin Roosevelt extolled the Tuskegee Center as “a perfect setting for a hospital unit to care for infantile paralysis victims” based in “a hospital completely staffed and directed by competent Negro doctors.”4 Neither Roosevelt nor O’Connor hinted at the political calculations that had led to the opening of the center. During the 1930s the systematic neglect of Black polio victims had become publicly visible and politically embarrassing. Most conspicuously, the polio rehabilitation center in Warm Springs, Ga, which Roosevelt, himself a polio survivor, had founded, accepted only White patients. This policy, reflecting the ubiquitous norm of race-segregated health facilities, was sustained by a persuasive scientific argument about polio itself. Blacks, medical experts insisted, were not susceptible to this disease, and therefore research and treatment efforts that focused on Black patients were neither medically necessary nor fiscally justified.

It was true that few Black polio victims were reported during the 1920s and 1930s, even with the growing number of epidemics in the Northeast and Midwest. And in the South, where the majority of Black Americans lived until after World War II, there were few outbreaks of polio at all. Nonetheless, leaders of the Black medical profession argued that too many Black polio cases were missed as the result of medical racism and neglect: families had limited access to doctors and hospitals, and inadequately trained Black health professionals were unable to diagnose polio’s ambiguous early symptoms. “I firmly believe,” Black orthopedist John Watson Chenault asserted, that the statistics used to argue for a lower incidence of disease among Blacks “are due to the notoriously poor treatment facilities available for Negroes and[,] as much as I hate to admit it, the failure of so many of our men to recognize the disease.”5

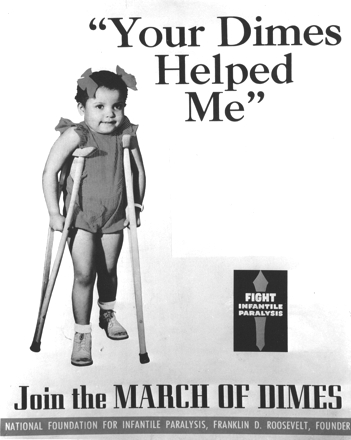

Only after a decade of pressure from Black activists was the notion of polio as a White disease effectively challenged. Funding from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (popularly called the March of Dimes) at first supported separatist health facilities such as the Tuskegee Center to care for Black polio survivors and to train Black health professionals. During the late 1940s, in response to civil rights activism and Cold War race politics, the foundation gradually began to use its funding to try to integrate training programs and health facilities. Officials featured Black boys and girls as March of Dimes poster children and boasted that the foundation’s efforts were contributing to a breakdown in medical segregation. With this change in philanthropy policy and the growing visibility of Black polio cases, the science of polio also shifted and the theory of polio’s racial susceptibility faded. Invigorated by this integrationist epidemiology, civil rights activists demanded that in polio, as in American medicine at large, health care should be provided “regardless of race, color or creed.”6 Black children were made part of the 1954 Salk vaccine trials and the subsequent national vaccination programs.7

Thus, it was a calculated convergence of politics, civil rights activism, and philanthropy that first made minority polio survivors visible, then affirmed that they deserved care from specialists (albeit in separate institutions), and finally, as the notion of polio as a White disease became disreputable, transformed Blacks into appropriate subjects of research and recipients of medical science advances. This new politics of polio made Black and White bodies analogous and forced a new epidemiology. Clinical visibility informed social awareness of neglect, which in turn empowered larger claims for social justice and medical equity.

POLIO, A WHITE DISEASE?

In the early decades of the 20th century, when polio epidemics first appeared in North America, medical professionals and the lay public shared the conviction that Blacks were rarely infected, whereas with Whites, polio was common and transcended class lines. Epidemiologists initially saw wealthy White polio patients as anomalies, best explained by an unlucky association with infected members of the urban poor.8 However, by the late 1920s, polio was reconceived as “everyone’s disease.”9

The low numbers of paralyzed Black children—in a 1924 Detroit epidemic, for example, there were only 5 in 300 cases10—did not surprise most medical experts. More susceptible to some diseases and impervious to others, the constitutions of “primitive” races were contrasted with the complex and delicate bodies of the “civilized” peoples of Northern European heritage. The most sophisticated expositor of this argument was Rockefeller Hospital clinician George Draper. A polio expert who had been studying the disease since the early 1910s and had directed Roosevelt’s own therapy in the 1920s, Draper believed that eugenic factors were at the heart of polio’s confusing epidemiology. In his 1917 text on polio, expanded in 1935, Draper pointed to the “well-grown, plump” White, native-born children with widely spaced upper front teeth and “delicate” teenagers who filled hospital beds and doctors’ offices during polio outbreaks.11 The argument that a child’s susceptibility could be the result of a constitutional makeup rather than an acquired immunity fit well within broader professional and popular assumptions about biological differences between Blacks and Whites.12 When White physicians studied Blacks as the “syphilis-soaked race,” for example, racialized genetics and social psychology combined. More vulnerable to syphilis, less susceptible to polio—both pieces of evidence were enlisted to establish the pathological and alien nature of the Black body.13

Today, we would argue that poverty, poor hygiene and nutrition, and unequal access to health care could explain most race disparities in health and disease in American history. Even at the time, there was a powerful piece of evidence that could have argued against the race theory of differential susceptibility: White Southerners, the other missing group in early 20th-century polio epidemics. Without widespread electrification or water filtration systems, the South had such a low level of sanitation (which led to mild infant infection and widespread adult immunity) that the region saw no major polio epidemics until the late 1940s.14 Yet polio clearly did affect Black communities. During the 1916 epidemic, for example, health officials in Maryland reported more Black cases than White cases but were unable to explain why.15

Facing a segregated health system and Black nurses and doctors without specialized training in polio, anxious families sought out any expert who claimed some scientific insight into the disease. During the 1920s, George Washington Carver, the eminent agricultural chemist at the Tuskegee Institute, began to use a special peanut oil he had developed to massage a few young men whose muscles had been debilitated by polio. In the early 1930s, he told reporters about his work, adding, “it has been given out that I have found a cure. I have not, but it looks hopeful.” Hundreds of people wrote to him, and families brought their paralyzed children to Tuskegee to ask his advice.16 In 1934, when a small group of Black Democrats decided to organize a ball as part of Roosevelt’s polio fundraising, they proposed naming the event after Carver, “the Tuskegee scientist, whose peanut oil products . . . have aided treatment for infantile paralysis.”17

WARM SPRINGS—A SEGREGATED POLIO REFUGE

By the time Roosevelt was elected to the White House in 1932, he had made polio—a disease he claimed to have conquered—his personal charity. During the 1920s, he bought Warm Springs, then a run-down thermal springs resort, and turned it into a polio rehabilitation center, formally incorporating it as the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, a nonprofit company eligible for tax-free gifts.18

Warm Springs gradually became a refuge for an elite group of the disabled. Merging medical and social rehabilitation, the center gave polio survivors the opportunity to recover physically and mentally. But from the beginning, this refuge was for White survivors only. Typical of the political calculations by Roosevelt’s New Deal administration, which fought the Depression with unprecedented federal funding while accepting racist policies that accommodated the Southern status quo, Roosevelt was careful not to challenge what he saw as Georgia’s “local customs” and kept the Warm Springs patients, administrators, and medical staff White.19

Of course, Blacks lived and worked at Warm Springs as maids, waiters, body servants (assistants used to lift disabled patients), laundresses, gardeners, and janitors. By the mid-1930s, 43 of 93 employees were Black. The center’s White employees lived in the main hotel and the surrounding housekeeping cottages; Black employees lived in a special “colored dormitory” and in the servants’ room in the hotel basement.20 The subservience and hard work expected of these employees was exemplified in Sarah, whom a Warm Springs patient praised in 1932 as a “most diverting person . . . tall, gaunt . . . with her sun hat and bony hands,” expert in “pouring olive oil on skins that have not known the sun, adjusting bathing suits, fetching towels, wheeling chairs . . . [and urging patients] ‘’Cose yo’ can learn to swim. . . . Fust thing yo’ knows yo’ll be going right across the pool by yo’self. Yas, ma’am.’”21

Roosevelt encouraged the trustees of the Warm Springs Foundation to use him as a patron for polio fundraising, and annual Birthday Ball campaigns began in 1934 (held annually on January 30, Roosevelt’s birthday). At first the funds were intended to create a permanent endowment for Warm Springs. But gradually the Birthday Ball organizers redirected the money to the local communities that had raised it. The significance of this philanthropic policy shift away from Warm Springs was not widely appreciated by the American public, however, and Warm Springs continued to be viewed as a national polio center.22

RACE, POLITICS, AND POLIO

Segregation at Warm Springs became a source of political disquiet when Roosevelt first ran for reelection in 1936. The close connection between the president and Warm Springs, a place he continued to use as a personal retreat, led those campaigning against him to scrutinize its admission policies as part of the fierce campaign. There were rumors that Warm Springs was a moneymaking scam for the Democratic Party and for Roosevelt personally. The president was also said to have deceived the American people about the effects of polio on his own body. According to a whispering campaign, polio had left him addicted to drugs, so erratic that he required a straightjacket, and was incontinent, sexually impotent, and helplessly crippled.23

One key ingredient in Roosevelt’s New Deal strategy was to remake the Democratic Party by attracting new voters, especially Blacks.24 During the 1936 presidential campaign, the Republican Party sought prominent Blacks to combat claims that the Democratic Party was the party of civil rights. Warm Springs policies became part of this debate, and distinctions between Roosevelt’s New Deal programs and the resort were frequently blurred. In a radio speech supporting Governor Alfred Landon for president, Marion Moore Day, the daughter of Frederick Randolph Moore, a former minister to Liberia, offered as evidence of the Democrats’ neglect the $100000 Blacks had contributed to the Warm Springs Foundation during the Birthday Ball celebrations, while “no Negro children suffering from infantile paralysis can be admitted there.”25 Reverend J.S. Bookens of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Mobile, Ala, tried to have his paralyzed 9-year-old son admitted to Warm Springs and was told “Negroes [are] never admitted to that institution.” This case was widely discussed in the Black press and spurred Walter White, secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, to remind Eleanor Roosevelt that segregation at Warm Springs was the reason his association refused to sponsor Birthday Ball fund raising.26 In a letter published in the Chicago Tribune, one angry writer cited Warm Springs to show how little New Deal officials cared about racial justice:

There is a place in Georgia named Warm Springs where the President has endowed, or partially maintains, a sanitarium for the treatment of infantile paralysis. I have no doubt but what the humblest, most ragged, and illiterate little white child in the land would be admitted there for treatment, but the most cultured, refined, and well clothed Negro child would be denied admittance simply because it was a Negro.27

Declining to answer such charges publicly, “because of the intense heat of this year’s presidential campaign,” Charles Irwin, chief surgeon at Warm Springs, prepared a 6-page response that could be sent out in reply to private inquiries, explaining why Warm Springs did not “accept colored patients.” Irwin frankly assumed the need for racial segregation at most medical facilities. Warm Springs, he said, was “not a general orthopedic hospital. It treats and studies nothing but Infantile Paralysis. It maintains no wards, separate clinics or segregated rooms. Aid and pay patients share the same facilities. We cannot take colored people for this reason.”28

Irwin’s second line of defense was about money:

The Trustees deem it more wise to spend public monies received for enlarging the national fight so that a greater number may be helped back home than to spend such monies in huge buildings duplicating existing orthopedic hospitals. We feel our national program is helping more colored people than the putting up of buildings and constructing of pools which could service but a small number.28

As polio fundraising was recast as a national campaign, Warm Springs’ admission policy became even more potent as a symbol of medical racism. “Since Negroes are contributing . . . and since they are sufferers of infantile paralysis,” a National Urban League official told Eleanor Roosevelt, the Birthday Ball campaign must include “their needs in the general program of curing and preventing this dreaded malady,” a change that “would be heartily welcomed by ten million otherwise socially disinherited American citizens.”29 Warm Springs segregation had become an awkward reminder of the Roosevelt administration’s reluctance to enforce social justice and civil rights.

DEFENDING MEDICAL SEGREGATION

Because it could be neatly buttressed by statistics, the susceptibility argument provided an expedient way to counter the groundswell of protests against racism in polio care. Still, it was a fragile defense, suggesting both that Black cases did not exist and that building separate health services for them was too expensive. Such arguments were familiar parts of what Cobb would describe as a policy of “secondhand hospitals” defended by White proponents as “not new, but . . . better than anything [a Negro] . . . has or can get now.”30

In 1936, Roosevelt was reelected with an extraordinary 76% of Black voters who chose, as one Black editor in Pittsburgh famously phrased it, to “turn the portrait of Lincoln to the wall.” Prominent intellectuals formed what was known as the Black Cabinet, an informal but influential group of New Deal advisors, and Black doctors, nurses, and social workers gained positions as administrators of some New Deal programs, although usually with little say about the eligibility and rights of their clients.31

Eleanor Roosevelt and, less enthusiastically, her husband began to urge the Warm Springs trustees to turn one of the center’s residential cottages into a house for patients of color and to build them a small pool for hydrotherapy. Just at this time the first formal epidemiological analysis of polio and race appeared. Written by Paul Harmon, a Chicago public health official, and published in the prestigious Journal of Infectious Diseases, it provided a strong argument for maintaining the status quo at Warm Springs.

“There has never been an adequate survey of the incidence of this disease among racial groups,” Harmon announced, and he made the question of race central by analyzing the numbers of Black and White and “Oriental” polio cases.32 Statistics from the 1916 New York epidemic, showing a Black morbidity rate of 241 per 100000 of population compared with 383 for Whites, suggested “that the disease is relatively infrequent in the colored race.”33

Harmon also analyzed outbreaks in the early 1930s in North Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi, which showed a 2 to 4 times higher incidence in the “white race,” and in the 1930 San Francisco epidemic, only 10 of 234 cases were Asian Americans, supporting the susceptibility theory.34 Harmon did include some disturbing counterevidence. Records showed a higher incidence of Black cases than White cases in Maryland in 1916 and in Chicago in 1930 and a higher fatality rate than Whites in New York’s 1931 epidemic.35 All of his statistics demonstrated significant numbers of Black polio survivors, but he felt that the epidemiological records were unreliable “for the difficulty that the negro presents to statisticians is real.” With tortured reasoning, Harmon suggested that higher mortality rates in New York might be the result of the “non-reporting of mild cases among negros [sic],” which would mean there were even more unrecognized Black cases. “It is possible that opportunity for contact infection” rather than a “genuine racial immunity . . . is the determining factor in the data reported,” Harmon concluded, but his doubtful tone allowed readers to remain skeptical of such a conclusion and left differential racial susceptibility uncontested as the best overall explanation.36

The politics of race and polio were exacerbated in early 1937 when an article on George Washington Carver in Reader’s Digest featured a photograph of Carver seated beside piles of letters from the parents of paralyzed children.37 Within weeks, in private letters, conversations, and memoranda, the White trustees of the Warm Springs Foundation and the Birthday Ball committee began to try to work out a solution.38 All the trustees disliked the idea of integrating Warm Springs, but many felt uncomfortable having to say so. Their discussions covered 3 issues: (1) the financial cost of installing separate facilities at Warm Springs, (2) the political cost of keeping Warm Springs White, and (3) the public relations risk of demonstrating that Warm Springs staff already treated the local Black community.

Trustee A. Graeme Mitchell, a pediatrician who directed Cincinnati’s Children’s Hospital, was convinced “that there is no chance of having a cottage for Negroes at Warm Springs.” It was obvious, Mitchell explained, that Black and White patients could not swim in the same pool or eat in the same dining room.39 Warm Springs Foundation Director O’Connor, Roosevelt’s longstanding friend and adviser, based his reluctance on the susceptibility argument, because “it has always been my understanding that the colored race was not very susceptible to this disease.” O’Connor drew the trustees’ attention to the special epidemiological analysis he had asked former Warm Springs physician Leroy Hubbard to complete, which concluded that “the attack rate in the colored race is somewhat lower than in the white, indicating that there may be a [sic] slightly less susceptibility.”40 Although O’Connor believed that only troublemakers like “professional colored promoters” were raising “this colored question,” he admitted that “we have a psychological problem which we probably should endeavor to meet to whatever extent we are not meeting it now.”41

In a similarly awkward defense that acknowledged the existence of Black polio patients, business manager Henry N. Hooper and chief surgeon Irwin insisted that the outpatient clinic at Warm Springs was already responsive to the needs of local Black health professionals and their “colored orthopedic patients.” “Where surgery is indicated,” Irwin noted, these patients were sent to “one of the Atlanta hospitals for colored people.”42 Hooper argued that the limited “susceptibility of the colored people” meant that only White patients could provide useful “material for education and for study by our orthopedic and physical therapy staffs.”43 In any case, Hooper added, as “our facilities do not lend themselves to the comfortable housing and treatment of resident colored cases . . . we do not feel that we could make such patients comfortable both physically and psychologically.”44

The trustees rejected the idea of a special cottage at Warm Springs for “colored victims” but agreed that the solution should be based on the familiar model of institutional separatism. Warm Springs officials were instructed to investigate “the possibility of our establishing relations with an institution already equipped for the care of colored people.”45 Perhaps at a new polio unit based in an established Black hospital that could train nurses, physical therapists, doctors, and brace makers, “considerably more would be accomplished, the results would be obtained at a lower cost and criticism would both be avoided and unjustified.”46 A separatist solution would enable Warm Springs to avoid breaching the comfort level of current patients and staff, angering local politicians and businessmen, and bringing medical racism into the public eye.

In August 1937, the announcement of the Birthday Ball’s expenditures for that year, with no mention of Tuskegee or any other Black institution, outraged Black community leaders who had organized fundraisers as a way of both fighting polio and showing their newfound support for the Democratic Party. Letters to Roosevelt, the Warm Springs trustees, and to Paul de Kruif, secretary of the Birthday Ball’s Research Committee and the nation’s most famous science journalist, were reprinted and debated in the Black press.47 De Kruif defended his committee’s neglect of Carver’s polio work with the unconvincing argument that Birthday Ball funds were available for prevention, not treatment. “In these crucial hours,” Chicago businessman James Hale Porter replied, “a scientific remedy from a student of this disease is an angel of mercy to suffering millions,” adding, with a pointed reference to de Kruif’s best-selling Microbe Hunters, “Dr. Carver’s work to civilization compares if history is true, with that of Pasteur, the eminent French chemist.”48 More sharply, a Chicago Defender article headed “We Donated, But They Left Us Out” claimed that the Warm Springs board of trustees, which “comprises some of the aristocrats of the South . . . took particular care not to include a Race institution in its research program” and had defended this policy by arguing that “the Negro should solve his problem with reference to this plague through local medical practitioners, because statistics show that it is most prevalent among White people.”49 Epidemiological statistics that were believed to prove polio’s differential racial susceptibility were being used to justify medical segregation and to deny Blacks legitimacy as both patients and scientists.

THE TUSKEGEE SOLUTION

In September 1937, Roosevelt announced the formation of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to “direct and coordinate the fight against this disease in all its phases.” The new foundation (soon known popularly by its campaign slogan, the March of Dimes) would be directed by O’Connor, and the president would not “hold any official position in it.” With Warm Springs trustees no longer in charge of national polio fundraising, the Georgia center could become just one of a number of regional centers caring for polio patients and training specialists.50

A few months before this announcement, the Tuskegee Institute’s Andrew Memorial Hospital had opened a small unit for disabled children and hired John Chenault, one of the nation’s few Black orthopedic surgeons, as its director. The 12-bed unit was a calculated step in a campaign by institute president Frederick Douglass Patterson and Midian Othello Bousfield, director of the Rosenwald Fund’s Division of Negro Health. Buttressed by support from Reverend J.S. Bookens, Mary Bethune, and other Black activists, and building on public interest in Carver’s polio work, Patterson and Bousfield were quietly urging O’Connor to consider Tuskegee as the site for a polio center.51

In April 1939, Roosevelt made his first official visit to the Tuskegee Institute. He praised the beauty of the campus, visited the Veterans Hospital and shook hands with patients in wheelchairs, and talked briefly with Carver.52 O’Connor came in May to speak at the institute’s commencement ceremonies, where he announced that the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis would fund the Infantile Paralysis Center.53 The 3-story redbrick building, designed by Tuskegee architect Louis E. Fry, officially opened in 1941.54 “Like many other institutions under the sponsorship of the National Foundation,” O’Connor proclaimed at the dedication, this new center would make “a valuable contribution to the solution of the problem,” and headed by the “brilliant young specialist” John Chenault, it was “destined to become a great orthopedic center for the Negro people of the United States.”55 But while arguing that polio was “notoriously no respecter of persons,” O’Connor simultaneously blamed the plight of “twisted, distorted and disabled children and adults” on the ignorance of Black parents who did not “know when, and how, and where” to secure “expert medical care” and who had not “abandon[ed] the superstitions and the traditions of an uninformed past.”56

The center quickly became a symbol of Black progress. Its national prominence enabled the staff to confront the theory of polio’s racial susceptibility and to make visible the neglect of disabled patients of color. In the Journal of the National Medical Association, Chenault directly addressed the susceptibility argument with his own analysis of evidence from Alabama and Georgia. Harmon’s work, he argued, had capably summarized previous epidemiological knowledge, but new evidence showed that Black patients’ unequal access to care and their physicians’ inadequate professional training had skewed the statistical reports, leaving “many features” of polio’s epidemiology “still debatable.”57

Meanwhile at the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, O’Connor hired university administrator Charles Hudson Bynum to direct the foundation’s new interracial activities division.58 In Negro Digest, Bynum reminded readers that the National Foundation provided funding “on the same basis that polio strikes—regardless of race, color or creed” and that there was “no evidence of any racial susceptibility to the disease.”59 In the New York Times, Bynum claimed that March of Dimes funding enabled hospitals nationwide to treat Black polio patients and Black physicians, nurses, and physical therapists to train at not only Tuskegee but also Black hospitals in Nashville, Tenn; Durham, NC; and Chicago, Ill. Training courses for polio emergency volunteers were now also open to Black women.60

Integration occurred more fitfully, but by the late 1940s, the fear that race discrimination at home could damage America’s Cold War prestige abroad meant that moderate civil rights measures could potentially “make credible the government’s argument about race and democracy.”61 In 1944 when the March of Dimes funded a nonsegregated polio hospital during a particularly fierce polio epidemic in Hickory, NC, a Black Baltimore, Md, newspaper pointedly noted that if disease is color blind, “there is cause to wonder why they can’t do the same thing the year round.”62 National foundation executives began to argue that their funding was contributing to a gradual breakdown in discrimination, including “notable reversals of admission policies of medical schools, associations, and hospitals.”63 A turning point came in September 1945 when Bynum announced at the annual meeting of National Medical Association’s board of trustees that Black polio patients were now being treated at Warm Springs.64

On the popular front, March of Dimes organizers began to encourage local chapters to integrate, arguing that “accurate statistics” now showed that “the disease attacked all races.” A few Black boys and girls were chosen for local, regional, and national campaigns.65 These slow changes in public relations and professional training did not resolve questions of access, however. Polio survivor Wilma Rudolph, future Olympic track star who won 3 gold medals in 1960, later recalled traveling 50 miles in a segregated bus with her mother from her home in Clarksville, Tenn, to be treated at Meharry’s polio clinic in Nashville.66

A NEW VISIBILITY

With the opening of the Tuskegee Infantile Paralysis Center and the prominent support of the nation’s largest disease philanthropy, Black leaders had a platform to talk in general about race and medicine, health care access, and the training of professionals. March of Dimes money shored up Tuskegee’s financial troubles, and by 1948 O’Connor had become president of the institute’s board of trustees. In November 1950, to commemorate the center’s 10th anniversary, 300 people came to hear speeches by O’Connor, Chenault, Bynum, and Mrs Bettye Steele Turner, the head of Tuskegee’s March of Dimes chapter.67 With a flourish of Cold War rhetoric O’Connor declared that “we must continue to broaden the field of opportunity to make places for our best brains, our most capable hands, our most dynamic personalities, whether they be Negro or white,” for “as a nation, we cannot continue to squander the abilities of our people without lessening our capacity for world leadership.”68 Highly visible to the audience was the impressive transformation that March of Dimes support had made in the renovation and expansion of institute buildings, including a new nursing school, nurses’ residence, and out-patient department.69

George Draper’s arguments about susceptibility, though, did not vanish. In a 1951 story reported as “Polio Strikes Negroes 1st in Louisiana,” a White physician speaking for the March of Dimes called a Shreveport, La, epidemic unusual because “usually polio strikes blonde, blue-eyed persons at a far greater rate.”70 Leading scientists, however, found the differential susceptibility theory less convincing. In 1946 Harry Weaver, newly appointed as director of research at the National Foundation, discovered this when he wrote to virologist Thomas Francis asking about research on race and polio: “I have been under the impression that most people believed that there was less poliomyelitis among Negroes than Whites.” No, Francis told Weaver, “the incidence by race . . . was essentially the same”; poor statistical collection had previously skewed the statistics and “there has been a tendency in the past not to seek out colored cases as well as White.”71

When Francis later directed the massive clinical trial of the Salk polio vaccine funded by March of Dimes, Black children were made part of the research, and Black medical leaders, including Chenault and Matthew Walker, president of the National Medical Association, were invited to attend the historic announcement ceremony at the University of Michigan. During the 1954 vaccine trial, Black activists praised the unusual integration of Black and White professionals as “white nurses assisted Negro physicians in administering the vaccine” and the way that “public health officials, many of whom had never taken notice of Negro children in the community[,] supervised the tests in person.” Black scientists and technicians at Tuskegee’s Carver Research Foundation produced the HeLa cells used for evaluating the vaccine.72 After the results were announced, Bynum, known in the Black press as “Mr Polio,” boasted that the results were a “triumph of racial cooperation.”73

This new science of polio, however, did not counter pervasive customs of medical racism. Thus, in May 1954, the month that the Supreme Court announced its Brown v. Board of Education decision, Black children in Montgomery, Ala, had to wait to receive their Salk shots on the front lawns of local White public schools. They were forbidden to use the restrooms inside.74

Warm Springs remained segregated for many years. By the end of the 1940s it had set up a few “emergency” beds for local Black patients, but there were no Black physicians, nurses, therapists, or administrators, and the Warm Springs movie theater had an indoor picket fence indicating where Black employees could sit, separate from the White patients and staff, in the worst seats, the two front rows.75 By the mid-1960s, the widespread use of the Salk and Sabin polio vaccines led to fewer polio cases and a less critical need for rehabilitative care. The Warm Springs center became primarily a tourist attraction commemorating the legacy of Franklin Roosevelt. In the 1980s, however, with the emergence of postpolio syndrome, the Warm Springs center’s history of rehabilitative expertise gave it new importance, and today the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation includes a postpolio clinic and other programs for brain injury rehabilitation, orthotics, and prosthetics.

Even before the national decline in polio cases, the Tuskegee Center began to represent an outdated symbol of medical accommodationism. By the mid-1950s many Black health professionals were no longer content to work with White business leaders to support separatist hospitals through what medical historian Preston Reynolds has called “well-established patterns of civility.”76 The new civil rights movement pervaded medicine, as physicians, nurses, and other activists began to work for “the death of Jim Crow.”77 During a 1957 March of Dimes campaign, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson refused to perform in a segregated hall and reminded local organizers of the March of Dimes’ national policy, “which is dedicated to all people, regardless of race.” She was not, she explained, “urging my people to turn their backs on the drive against polio. I know what sickness is. I think race hatred is a sickness too.”78 Amid the slow desegregation of hospitals across the South, the Tuskegee Center lost its regional distinctiveness, and in 1975 it closed its doors.79

CONCLUSION

The struggle to desegregate Warm Springs and to vanquish racism in polio care and specialist training was a difficult battle fought at a time when polio, race, and politics converged on the national stage. During the 1910s and 1920s defenders of medical segregation had argued that Blacks were simply not susceptible to the disease, but epidemiological statistics nonetheless revealed numbers of Black polio cases whose very existence, activists pointed out, had been kept invisible by medical racism and neglect. By the 1930s, polio became a civil rights issue that Roosevelt’s Democratic advisers and the directors of the Warm Springs center could not ignore. The building of a special center for rehabilitative care and professional training at Tuskegee, funded by the March of Dimes, ran in tandem with the US Public Health Service’s Tuskegee syphilis experiment. But polio lacked the virulent racist connotations associated with a sexually transmitted disease. More than this, the sentimentalized appeal of disabled children, rather than adults facing the so-called penalties of promiscuity, helped to make polio a more palatable issue for civil rights activism.

The fight to desegregate Warm Springs made visible the narratives of Black patients and emboldened claims for compassion and equity.80 Although medical practices remained infused with racism, the turmoil allowed the appalling inequities in access and quality of care among disabled minorities and the idea of polio as a White disease to come under critical scrutiny. Under the leaky umbrella of Roosevelt’s pluralist New Deal, although conspicuously without its proactive support, Blacks were able to alter the official record and assert the right to an equal standard of health care. As the fight against Jim Crow medicine grew more forceful in the 1950s, Blacks—now recognized as susceptible to the polio virus and as deserving recipients of the advances of medical science—waited eagerly for their children to receive the Salk vaccine. But all too often it was offered to children waiting on the lawn outside the local White school door.

Figure 1.

The Infantile Paralysis Center at the Tuskegee Institute, c. 1945.

Source. March of Dimes Archives, White Plains, NY.

Figure 2.

Rita Reed from Blue Island, Ill, the first African American March of Dimes poster child, 1947.

Source. March of Dimes Archives, White Plains, NY.

Figure 3.

White guests and black waiters at the Warm Springs dining room, c. 1950.

Source. March of Dimes Archives, White Plains, NY.

Figure 4.

Warm Springs movie theater interior, with white picket fence separating White patients and staff from Black employees, c. 1950.

Source. March of Dimes Archives, White Plains, NY.

Figure 5.

March of Dimes official Charles H. Bynum accepting a check from Mrs J. A. Jackson, secretary of the Grand Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star of Virginia, December 3, 1955.

Source. Afro-American Newspaper Archives and Research Center, Baltimore, Md.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to David Arguss, Ted Brown, Elizabeth Fee, Meg Hyre, Beth Linker, Steven Mawdsley, David Rose, Emilie Townes, John Harley Warner, and Daniel Wilson for their comments and suggestions; to Marilyn Benaderet at the Afro-American Newspapers Archives for her assistance in tracking down photographs; and to David Rose at the March of Dimes Archives for all his research help.

Human Participant Protection No human subject research was involved in this study.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.“Paralysis Center Set Up for Negroes,” New York Times, May 22, 1939.

- 2.O’Connor Basil, “Education in Infantile Paralysis: An Address” (15 January 1941), quoted in Edith P. Chappell and John F. Hume, “A Black Oasis: Tuskegee’s Fight Against Infantile Paralysis, 1941–1975” (Tuskegee University, 1987, unpublished), copy in March of Dimes Archives, White Plains, NY, 194.

- 3.Montague Cobb W., Medical Care and the Plight of the Negro (New York: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 1947), 6.

- 4.“Statement at the Dedication of the Infantile Paralysis Unit,” Atlanta Daily Herald, February 6, 1940.

- 5.John W. Chenault, “Infantile Paralysis (Acute Anterior Poliomyelitis),” Journal of the National Medical Association 33 (1941): 220–26, quote 221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charles H. Bynum, “Dimes Against Death,” Negro Digest 5 (1947), 82. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jane S. Smith, Patenting the Sun: Polio and the Salk Vaccine (New York: William Morrow, 1990), 273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.See Rogers Naomi, Dirt and Disease: Polio Before FDR (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992); John R. Paul, A History of Poliomyelitis (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1971); Tony Gould, A Summer Plague: Polio and Its Survivors (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995); Daniel J. Wilson, Living with Polio: The Epidemic and Its Survivors (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); and Amy L. Fairchild, “The Polio Narratives: Dialogues with FDR,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 75 (2001): 488–534. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.But see one contemporary argument against this “central dogma” of polio epidemiology, supporting “the power of genes in determining susceptibility” (51) with questions such as “could there be something about race, something in your genes, that makes you less—or more—likely to get polio?” (48) and “apparently the poliovirus has a peculiar affection for Germanic fold and southern Europeans” (49); Richard L. Bruno, The Polio Paradox: Uncovering the Hidden History of Polio to Understand and Treat “Post-Polio Syndrome” and Chronic Fatigue (New York: Warner Books, 2002).

- 10.Paul H. Harmon, “The Racial Incidence of Poliomyelitis in the United States with Special Reference to the Negro,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 58 (1936): 331. For an important analysis of race and the history of epidemiology see Harry M. Marks, “Epidemiologists Explain Pellagra: Gender, Race and Political Economy in the Work of Edgar Sydenstricker,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 58 (2003): 34–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draper quoted this description from his 1917 text Acute Poliomyelitis in his later, more popular book Infantile Paralysis (New York: Appleton-Century, 1935), 59; see also Paul, History, 161–66; Gould, Summer Plague, 70–73.

- 12.On theories of acquired immunity during the 1910s, see Paul, History, 131–33. On research projects (probably inspired by George Draper’s work) funded by Rockefeller Foundation during the 1916 epidemic that included detecting “physical characteristics,” see Paul, History, 152. On the history of race and disability, see Douglas C. Baynton, “Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History,” in Paul K. Long-more and Lauri Umansky, eds., New Disability History: American Perspectives (New York: New York University Press, 2001), 33–57.

- 13.See, for example, Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Pantheon, 1997); James H. Jones, Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment (London: Free Press, 1981); Vanessa Northington Gamble, Making a Place for Ourselves: The Black Hospital Movement, 1920–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); and Susan M. Reverby, “More Than a Metaphor: An Overview of the Scholarship of the Study,” in Tuskegee’s Truths: Rethinking the Tuskegee Study, ed. Susan M. Reverby (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 1–11.

- 14.On White patients’ experiences of polio care in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, see Kathryn Black, In the Shadow of Polio: A Personal and Social History (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1996); Thomas M. Daniel and Frederick C. Robbins, eds., Polio (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997); and Edmund J. Sass with George Gottfried and Anthony Sorem, eds., Polio’s Legacy: An Oral History (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1996).

- 15.Harmon, “Incidence,” 333.

- 16.“May See Paralysis Treatment,” New York Times, October 31, 1933; “Peanut Oil Helps in Paralysis Cure,” Washington Post, December 31, 1933; “Mineral Oil Helps Cure Ailing Boys,” Los Angeles Times, January 1, 1934; “Cripples Beg Cure of Negro Scientist,” Washington Post, January 7, 1934. On Carver’s polio work, see Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 242–55; and Rackham Holt, George Washington Carver: An American Biography (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co, 1943), 299. For Carver’s description of the 2020 letters he had received during 1934, see Carver to Mrs Hardwick, December 16, 1934, reprinted in Gary R. Kremer, George Washington Carver: In His Own Words (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1987), 146. On Roosevelt’s tactful responses to Carver, see David M. Oshinsky, Polio: An American Story (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 66.

- 17.McMurry, Scientist and Symbol, 253–54; “Negro Citizens to Give Ball for Roosevelt,” Washington Post, January 14, 1934.

- 18.“Georgia” was probably added because there were other well-known warm springs linked to health resorts. On Roosevelt and Warm Springs, see Hugh Gregory Gallagher, FDR’s Splendid Deception (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1985); Dawn W. Houck and Amos Kiewe, FDR’s Body Politics: The Rhetoric of Disability (College Station, TX: Texas A&M Press, 2003); Theo Lippman Jr., The Squire of Warm Springs: F.D.R. in Georgia, 1924–1945 (Chicago: Playboy Press, 1977); and Turnley Walker, Roosevelt and the Warm Springs Story (New York: A. A. Wyn, 1953).

- 19.See Katznelson Ira, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Norton, 2005), 42; Wilson, Living with Polio, 75–76.

- 20.Carpenter Arthur, “Special Report to Trustees: Georgia Warm Springs Foundation,” March 1, 1933, President’s Secretary’s File, Subject: Warm Springs: 1933, Box 170, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, Hyde Park, NY.

- 21.Reinette Lovewell Donnelly, “Playing Polio at Warm Springs,” Polio Chronicle 1 (1932): n.p. On Roosevelt’s personal efforts to give “Aunt Sarah” an “old-age security” pension, see Walker, Roosevelt and the Warm Springs Story, 260–261.

- 22.See Sills David L., The Volunteers: Means and End in a National Organization (Glencoe, Ill: Free Press, 1957), 42–43; Paul, History, 305–307; Lippman, Squire of Warm Springs, 203–204.

- 23.See Wolfskill George and John A. Hudson, All But the People: Franklin D. Roosevelt and His Critics, 1933–1939 (London: Macmillan, 1969), 4–16; and Lippman, Squire of Warm Springs, 64–67, 187–198.

- 24.Kevin J. McMahon, Reconsidering Roosevelt on Race: How the Presidency Paved the Way to Brown (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

- 25.“Affront to Negro Laid to New Deal,” New York Times, November 1, 1936.

- 26.“Colored Help Warm Springs; Can’t Get Aid,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1936; “Application of Race Lad to Warm Springs Signal for Buck Passing,” Chicago Defender, October 24, 1936. See also “Warm Springs Bars Negro Boy,” New York Sun, October 14, 1936; and Walter White to Eleanor Roosevelt, October 20, 1936, both quoted in Chappell and Hume, “A Black Oasis,” 34–37.

- 27.George W. Holbert, “Reply to Mr. Ickes,” Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1936.

- 28.Irwin C.E., “[Report on] Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, Warm Springs, Georgia,” October 20, 1936, President’s Secretary’s File, Subject: Warm Springs: 1936, Box 170, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, Hyde Park, NY.

- 29.Jesse O. Thomas to Mrs Roosevelt [abstr], January 25, 1938, President’s Personal File 76, Warm Springs, Georgia, 1938, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, Hyde Park, NY.

- 30.Cobb, Medical Care and the Plight of the Negro, 20; see also “Voices From the Past: Medical Progress and African Americans,” American Journal of Public Health 92 (2002): 191–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nancy J. Weiss, Farewell to the Party of Lincoln : Black Politics in the Age of FDR (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983); McMahon, Reconsidering Roosevelt on Race; Darlene Clark Hine, “Black Professionals and Race Consciousness: Origins of the Civil Rights Movement, 1890–1950,” Journal of American History 89 (2003): 1279–94.

- 32.Harmon, “The Racial Incidence of Poliomyelitis,” 331.

- 33.Ibid.

- 34.Ibid., 332–36.

- 35.Ibid., 333.

- 36.Ibid., 336. After the 1936 polio epidemic in Chicago, the governor of Illinois set up a new division for handicapped children with Harmon as its first director.

- 37.McMurry, Scientist and Symbol, 253; James Saxon Childers, “A Boy Who Was Traded for a Horse,” American Magazine (1932), reprinted in Reader’s Digest 30 (1937): 5–9; and see “Ex-Slave Aids Paralytics,” New York Times, July 20, 1937.

- 38.O’Connor Basil to My Dear Mr President, March 3, 1937, President’s Secretary’s File, Subject: Warm Springs: 1937, Box 171, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, Hyde Park, NY.

- 39.“Memorandum of replies re question of a cottage for negroes at Warm Springs,” [enclosed with] O’Connor to My Dear Mr President, March 3, 1937.

- 40.“Memorandum: Poliomyelitis, in relation to white and colored populations in U.S.,” Leroy W. Hubbard to Basil O’-Connor, March 9, 1937, [enclosed in] Basil O’Connor to Dear Mr President, March 10, 1937, President’s Secretary’s File, Subject: Warm Springs: 1937, Box 171, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, Hyde Park, NY.

- 41.O’Connor to My Dear Mr President, March 3, 1937.

- 42.“Memorandum of replies.”

- 43.Hooper Henry to Dear Mr O’Connor, May 8, 1937, President’s Personal File 76, Warm Springs, Georgia, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, Hyde Park, NY.

- 44.“Memorandum of replies.”

- 45.O’Connor to My Dear Mr President, May 11, 1937.

- 46.Hooper to O’Connor, May 8, 1937.

- 47.Porter James Hale to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, August 3, 1937 [letter reprinted] in “What The People Say,” Chicago Defender, August 14, 1937.

- 48.“Urges Nation Use Dr. Carver in Infantile Paralysis Fight,” Chicago Defender, September 25, 1937.

- 49.“We Donated, But They Left Us Out,” Chicago Defender, August 7, 1937.

- 50.Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Foreword,” Annual Report of Georgia Warm Springs Foundation 1940, Disability History Museum, http://disabilitymuseum.org/lib/docs/2168.htm (accessed January 31, 2007).

- 51.Walcott, “Tuskegee Institute Infantile Paralysis Center,” 14; “Dr J. S. Brookens, AME Editor, Dies On Train,” Chicago Defender, September 22, 1951; “Roosevelt to See Noted Dr. Carver on Tuskegee Visit,” Birmingham Age-Herald, March 30, 1939. For the broader picture on Black medical leaders and philanthropic funding, see P. Preston Reynolds, “Dr Louis T. Wright and the NAACP: Pioneers in Hospital Racial Integration,” American Journal of Public Health 90 (2000): 883–87; W. Michael Byrd and Linda A. Clayton, An American Health Dilemma: Race, Medicine, and Health Care in the United States, 1900–2000 (New York: Routledge, 2002); Hine, “Black Professionals and Race Consciousness,” 1279–94; and E. H. Beardsley, “Making Separate, Equal: Black Physicians and the Problems of Medical Segregation in the Pre-World War II South,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 57(1983): 382–396. [PubMed]

- 52.“Roosevelt Thrilled by Tuskegee Choir”; “President Meets Dr. Carver, Tuskegee Wizard,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 8, 1939.

- 53.Chappell and Hume, “A Black Oasis,” 42.

- 54.“Statement at the Dedication of the Infantile Paralysis Unit”; “Infantile Paralysis to Be Treated Here,” Atlanta Daily Herald, February 6, 1940.

- 55.O’Connor, “Education in Infantile Paralysis,” 196–97; see also O’Connor’s address quoted in “New Polio Center to Aid Negro Paralysis Victims,” Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, June 25, 1939.

- 56.O’Connor “Education in Infantile Paralysis,” 194, 195; see also “‘Do Ye Also Unto Them,’” Black Dispatch (Oklahoma City), January 18, 1941.

- 57.Chenault, “Infantile Paralysis,” 221. See also Chenault’s speech at the ground breaking ceremony for the Tuskegee Center in January 1940, on “recent surveys” which showed “no appreciable variation between the white and Negro races”; “Infantile Paralysis Center Launched at Tuskegee,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, January 12, 1940.

- 58.“Negro Polio Victims Gets Foundation Aid,” New York Times, December 21, 1945.

- 59.Charles H. Bynum, “Dimes Against Death,” Negro Digest 5 (1947), 82. [Google Scholar]

- 60.“Negro Polio Victims Aided in All States,” New York Times, December 18, 1946; “Negro Groups Aided by Polio Foundation,” New York Times, January 9, 1949.

- 61.Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 14.

- 62.“$329.03 Is Raised in Atlanta Polio Drive,” Atlanta Daily World, February 7, 1941; “Disease Knows No Color Line,” (Baltimore) Afro-American, January 1, 1949.

- 63.Worthingham Catherine, “Professional Education and Poliomyelitis,” Journal of the National Medical Association 43 (1951): 24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.“Says Warm Springs Treats Negro Polio Victims Now, Atlanta Daily Herald, September 8, 1945; “Warm Springs Treats Negro Polio Victims,” Chicago Defender, September 8, 1945.

- 65.Darr Robert, “The Deep South Speaks,” Louisiana Weekly, January 18, 1947; “Polio Grants Made to Train Negroes,” New York Times, September 26, 1947; “Marching Against Polio,” Atlanta Daily World, January 14, 1948. The 1947 poster girl “Negro child Rita Reed” was a 5-year-old polio patient from Blue Island, IL; Joe Willie Brown was a poster boy for the 1948 campaign.

- 66.Rudolph Wilma, Wilma (New York, NY: Signet Books, 1977), cited in Wilson, Living with Polio, 146.

- 67.“Tuskegee to Hold Polio Conference,” New York Times, November 26, 1950.

- 68.“Negro Leaders’ Contribution in Field of Health Praised by Basil O’Connor, President of National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis,” Globe and Independent (Nashville), December 1, 1950; “O’-Connor Praises Contribution of Negro Leaders to Health,” Montgomery (Alabama) Advertiser, November 28, 1950.

- 69.Carter Kimberly Ferren, “Trumpets of Attack: Collaborative Efforts between Nursing and Philanthropies to Care for the Child Crippled with Polio 1930 to 1959,” Public Health Nursing 18 (2001): 254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.“Polio Strikes Negroes 1st in Louisiana,” Washington Post, August 21, 1951.

- 71.Weaver Harry to Thomas Francis, December 6, 1946; Francis to Weaver, December 10, 1946; quoted in Oshinsky, Polio, 66–67.

- 72.“Salk Vaccine Effectiveness Is Tribute to Cooperation,” (Baltimore) Afro-American, April 23, 1955; R.W. Brown and J. H. Henderson, “The Mass Production and Distribution of HeLa cells at the Tuskegee Institute, 1953–55,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 38 (1983): 413–431. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Enoc P. Waters, “Salk Vaccine Is Triumph of Racial Cooperation,” Chicago Defender, April 23, 1955.

- 74.Wright Bea in McCutcheon Transcript, quoted in Smith, Patenting the Sun (New York: William Morrow, 1990), 273.

- 75.Charles H. Bynum, “Upholding a Pledge,” Opportunity 24 (1946): 22. After outrage at their poor treatment, these patients were removed to a general hospital in Atlanta; “Don’t Say We Didn’t Tell You,” Chicago Defender, April 5, 1947; “Polio Grants Made to Train Negroes,” New York Times, September 26, 1947; Gould, Summer Plague, 189–191; Photo Album, Box 3, photos 909 and G418, Georgia Warm Springs Foundation Record, March of Dimes Archives; and see Elaine M. Strauss, In My Heart I’m Still Dancing (New Rochelle, NY: self published, 1979), 90–91, cited in Fairchild “The Polio Narratives,” 531, fn. 211. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reynolds P. Preston, “Hospitals and Civil Rights, 1945–1963: The Case of Simkins v Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital,” Annals of Internal Medicine 126 (1997): 898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hine, “Black Professionals and Race Consciousness,” 1294; and see Gamble, Making a Place for Ourselves, and P. Preston Reynolds, “Professional and Hospital Discrimination and the US Court of Appeals Fourth Circuit 1956–1967,” American Journal of Public Health 94 (2004): 710–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.“Race Bias Stops Mahalia Jackson,” Chicago Defender, January 19, 1957.

- 79.Chappell and Hume, “A Black Oasis.”

- 80.On the dynamics of civil rights and clinical visibility, see Keith Wailoo, Dying in the City of the Blues: Sickle Cell Anemia and the Politics of Race and Health (Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina University Press, 2001).