Abstract

Malaria pigment hemozoin was reported to activate the innate immunity by Toll-like receptor (TLR)-9 engagement. However, the role of TLR activation for the development of cerebral malaria (CM), a lethal complication of malaria infection in humans, is unknown. Using Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbA) infection in mice as a model of CM, we report here that TLR9-deficient mice are not protected from CM. To exclude the role of other members of the TLR family in PbA recognition, we infected mice deficient for single TLR1, -2, -3, -4, -6, -7, or -9 and their adapter proteins MyD88, TIRAP, and TRIF. In contrast to lymphotoxin α-deficient mice, which are resistant to CM, all TLR-deficient mice were as sensitive to fatal CM development as wild-type control mice and developed typical microvascular damage with vascular leak and hemorrhage in the brain and lung, together with comparable parasitemia, thrombocytopenia, neutrophilia, and lymphopenia. In conclusion, the present data do not exclude the possibility that malarial molecular motifs may activate the innate immune system. However, TLR-dependent activation of innate immunity is unlikely to contribute significantly to the proinflammatory response to PbA infection and the development of fatal CM.

Worldwide, 1 to 2 million persons die each year of malaria.1 The majority of these deaths are attributable to cerebral malaria (CM), in which patients fall into coma and suffer occlusion of brain microvessels by parasitized erythrocytes.2 The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes into brain vessels is not fully understood.3 Several studies using antibodies, recombinant cytokines, or genetically deficient mice have documented that secretion of cytokines of the inflammatory (Th1) pathway, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), lymphotoxin-α (LT-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), are important for the appearance of cerebral signs during malaria.4,5,6 It has also been demonstrated that these cytokines induce an up-regulation of adhesion molecules on blood vessel endothelia, eg, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), which may contribute to the microvascular lesions leading to CM. After infection with Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbA), a murine malaria parasite that causes CM, we showed that ICAM-1 is essential for the development of murine CM, as ICAM-1-deficient mice are protected against this form of the disease.7 We reported that the absence of TNF and LT-α protected from CM,5 and Engwerda and colleagues8 demonstrated that locally up-regulated LT-α is essential for CM development.

Pattern recognition receptors play a critical role for pathogen sensing and activation of the host innate immune response.9,10 Little is known with respect to Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation by malaria-associated molecules and their role for inducing the host innate immune response. Malaria pigment hemozoin from the Plasmodium falciparum parasite has recently been shown to activate dendritic cells through TLR9 activation in vitro.11 Further, the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor of P. falciparum parasite is recognized by TLR2 and TLR4.12 The GPI anchor may be required for the development of CM because immunization against GPI is protective.13,14 Further, we showed that in vitro activation of natural killer (NK) cells by the human parasite P. falciparum is TLR2-, -9-, and -11-independent but MyD88-dependent.15

Here, we investigated the role of TLR-dependent pathways for the control of murine blood stage malaria infection using the PbA strain leading to fatal CM using TLR-deficient mice. We demonstrate here that mice deficient for TLR9, several other TLRs, or TLR adaptors develop severe and fatal CM, suggesting that disruption of the innate immune signaling through TLR does not prevent fatal PbA-induced disease.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice deficient for TLR1,16 TLR2,17 TLR3,18 TLR4,19 TLR6,20 TLR7,21 TLR9,22 TIRAP,23 and MyD8824 were obtained from Dr. S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan); TrifLps2 from Dr. K. Hoebe (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA)25; and mice deficient for LT-α26 or CD1427 were bred in our animal facility at the Transgenose Institute (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Orleans, France). All mice were on the C57BL/6 genetic background (backcrossed at least 10 times beside TIRAP-deficient mice that were backcrossed seven times), and wild-type C57BL/6 (WT) mice were used as control. For experiments, adult (6 to 10 weeks old) mice were kept in filtered cages in a P2 animal facility. All animal experiments complied with the French Government’s ethical and animal experiments regulations.

Experimental Malaria Infection

PbA transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein were obtained from Dr. A. Waters (Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands).28 Mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of 106 parasitized erythrocytes as described previously.5 The mice were observed daily for clinical neurological signs of CM culminating in ataxia, paralysis, and coma. Parasitemia was analyzed by flow cytometry28 once per week, hematological parameters were assessed at regular intervals. Before succumbing to neurological signs, mice were sacrificed for histological analysis of the brain, lung, and liver.

Primary Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophage Cultures

Murine bone marrow cells were isolated from femurs and cultivated (106/ml) for 7 days in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 2 mmol/L l-glutamine and 2 × 10−5 mol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 20% horse serum, and 30% L929 cell-conditioned medium (as a source of M-CSF29). After resuspension in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 4°C), washing, and reculturing for 3 days in fresh medium, the cell preparation contained a homogenous population of macrophages (verified periodically by Giemsa staining and CD11b expression). The bone marrow-derived macrophages were plated in 96-well microculture plates at a density of 105 cells/well in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 2 mmol/L l-glutamine and 2 × 10−5 mol/L β-mercaptoethanol and stimulated with 100 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli, serotype O111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.125 μmol/L CpG ODN1826 (CpG; 5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3′), and parasitized red blood cells (freeze-thawed at 3 and 10 × 105 cells/ml) in the presence of IFN-γ (500 U/ml). After 20 hours of stimulation, the supernatants were harvested and analyzed immediately or stored at −20°C until further use. The absence of cytotoxicity of the stimuli was controlled using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium incorporation.

Cytokine Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Supernatants were harvested and assayed for cytokine content using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reagents for TNF and interleukin (IL)-6 (Duoset R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK).

Assessment of Vascular Leak

Mice were injected intravenously with 0.2 ml of 1% Evans blue (Sigma-Aldrich) on day 7, shortly before the death of the WT mice. One hour later, mice were sacrificed, and the coloration of brain sections was assessed. Lung and brain extravasation in formamide (Sigma-Aldrich) was quantified by absorbance at 610 nm of the tissue extracts as an indicator of increased capillary permeability, as described.5

Hematology

Blood was drawn into tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Vacutainer; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Grenoble, France), from five normal control mice and infected mice. Blood was homogenized and blood cell composition determined using a five-partdifferential hematology analyzer (model MS 9.5; Melet Schloesing Laboratoires, Osny, France).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

For histological analysis of cerebral pathology, brains, lungs, and livers from PbA-infected mice were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered saline formaldehyde for 72 hours, and 3-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Microscopic alterations were assessed with a semiquantitatively using a score (0 to 5) by two independent observers. Frozen sections (5 μm) of the brain were incubated overnight at 4°C with purified rat anti-mouse ICAM-1 antibody (clone YN1/1.7.4; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) diluted in PBS after saturation with normal rabbit serum. After washing, sections were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), followed by the addition of horseradish peroxidase-avidin, and colorimetric reaction was obtained using the 3-amino,9 ethyl-carbazole chromogen (ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin before mounting. The ICAM-1 staining was evaluated semiquantitatively.

Parasitemia

Parasitemia was assessed in 2 μl of tail blood collected at 7, 11, 18, and 22 days after infection with enhanced green fluorescent protein-PbA. Blood was diluted in 2 ml of PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin. The cells were then analyzed in FACScan flow cytometer LSR (Becton, Dickinson and Company) using CellQuest software (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Parasitemia in lung and liver was quantified in tissue homogenates and expressed as green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean values and SD indicated by error bars, if not otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was determined with Graph Pad Prism software (version 4.0; San Diego, CA) by means of nonparametric analysis of variance test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test for some data or log rank test; for others, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In Vitro TNF Production to PbA-Parasitized Erythrocytes Is MyD88- and TLR9-Dependent

To ascertain that erythrocytes infected with the murine parasite induce a TLR9-dependent proinflammatory response as reported for human parasites and hemozoin,11 we stimulated bone-derived macrophages from WT, TLR9-deficient, and MyD88-deficient mice with PbA-parasitized erythrocytes. We used the TLR4 and TLR9 agonists LPS and CpG, respectively, as reference compounds for the MyD88- and TLR9-dependent responses. In the absence of MyD88, the response to LPS- and PbA-parasitized erythrocytes was strongly reduced, in terms of TNF or IL-6 secretion, and the response to CpG was completely abrogated (Figure 1, A, C, and E). TLR9-deficient macrophages were unable to respond to CpG and exhibited only a partially reduced response to PbA-parasitized erythrocytes, in terms of TNF secretion (Figure 1B), which did not reach statistical significance for IL-6 secretion (Figure 1F). Therefore, these data confirmed an implication of TLR9, and more prominently MyD88, in the macrophage response to parasitized erythrocytes. The remaining stimulation seen in MyD88-deficient macrophages indicates a partial MyD88-independent response, such as the TRIF-mediated response to LPS stimulation. Based on the in vitro results, we tested the hypothesis that the development of PbA-induced CM is abrogated in TLR- and MyD88-deficient mice.

Figure 1.

Cytokine production by macrophages derived from MyD88- and TLR9-deficient mice. Bone marrow-derived macrophages from WT, MyD88-deficient (MyD88), or TLR9-deficient (TLR9) mice were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml), CpG (0.125 μmol/L), and noninfected (RBC NI) or parasitized red blood cells (PbA at 3 or 10 × 105 cells per ml). After 20 hours, the culture supernatants were analyzed for concentrations of TNF (A–D) and IL-6 (E, F). Results are from one representative experiment (n = 2 mice per genotype) of three independent experiments; the differences in response to LPS, CpG, and PbA between WT and MyD88-deficient mice were all statistically significant whereas statistically significant differences between WT controls and TLR9-deficient mice were seen merely for CpG and PbA 10× stimulated TNF (P < 0.05).

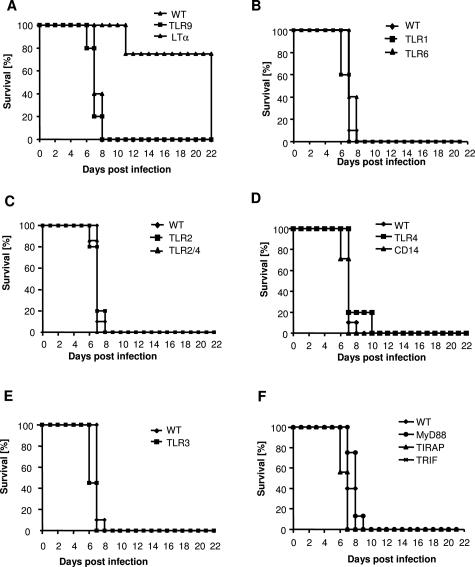

Development of CM in TLR-Deficient Mice

To analyze the biological relevance of the TLR9-dependent activation of innate immunity by P. falciparum,11 TLR9-deficient and WT mice were injected with 106 PbA-infected erythrocytes, which typically causes fatal CM within 6 to 9 days3 (Supplemental Figure 1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org for dose titration, survival, and parasitemia). WT control and TLR9-deficient mice developed typical neurological signs of CM within 7 days, which included postural disorders, impaired reflexes and loss of grip strength, progressive paralysis, and coma. WT and TLR9-deficient mice died between days 7 and 8 (Figure 2A). LT-α-deficient mice, included in the experiments as a resistant strain, did not develop CM, consistent with previous results,8 but developed a progressive parasitemia (see Figure 5A) and severe anemia by day 22 when they had to be sacrificed (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Survival from PbA-infected TLR-deficient mice. WT mice or those deficient for TLR9 or LT-α (A); TLR1 or TLR6 (B); TLR2 alone or plus TLR4 (C); TLR4 or CD14 (D); TLR3 (E); or MyD88, TIRAP, or TRIF (F) were infected with 106 PbA-parasitized red blood cells and the survival monitored daily. Results are given as Kaplan-Meyer curves of n = 7 mice per group pooled from two independent experiments. There was no statistically significant difference between the WT controls and the genetically deficient mice, except for LT-α-deficient mice (P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Parasitemia and hematological alterations are TLR-independent. The percentage of parasitized erythrocytes in the peripheral blood was determined by analyzing GFP fluorescent erythrocytes using flow cytometry (A) on day 7 for all TLR pathway-deficient mice and on days 7, 11, 18, and 22 after infection for resistant LT-α-deficient mice (B). Total platelet, leukocyte, lymphocyte, neutrophil, and erythrocyte counts were determined in the peripheral blood of control WT and MyD88-, TLR2-, and LT-α-deficient mice (C–G). The data represent the mean ± SD of n = 5 mice per group from two independent experiments (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). NI, noninfected mice. n.s., not significant.

Because TLR9-deficient mice are sensitive to CM, and GPI membrane anchor of P. falciparum was reported to be recognized by TLR2 and TLR4,12 we asked whether mice deficient for TLR2 or TLR4 or other members of the TLR family might be involved in the resistance to CM development. We investigated the response to PbA infection of a series of mice single and double deficient for TLR2 and -4 but also deficient for TLR1 or -6, which heterodimerize with TLR2 or TLR3. All tested mice were sensitive for the development of fatal CM with a mean survival between 6 and 8 days (Figure 2, B–E). Further, mice deficient for CD14, a co-receptor of TLR2, TLR4, and possibly other TLRs,30 developed fatal CM within 6 to 8 days after PbA infection (Figure 2D).

Finally, we assessed the role of the TLR signaling pathways by analyzing the course of PbA infection in mice deficient for critical TLR adapter molecules such as MyD88, TIRAP, and TRIF. MyD88-, TIRAP-, and TRIF-deficient mice were all highly sensitive to CM development, dying within 6 to 8 days, similar to WT control mice (Figure 2F). Therefore, the development of CM after PbA infection occurs independently of all TLR pathways investigated.

Microvascular Pathology in the Brain in the Absence of TLR Signaling

Because the neurological signs of CM are identical between WT and TLR9-deficient mice, we asked whether morphological investigations might reveal subtle local differences. First, we studied the cerebral vascular leak after intravenously injected Evans blue in mice with end-stage CM. Consistent with our previous data,5 WT mice displayed a distinct vascular leak as shown by a massive blue staining of the brain, which was absent in the CM-resistant LT-α-deficient mice (Figure 3A). By contrast, distinct vascular leak, identical to that of WT controls, was found in MyD88-deficient (Figure 3A) and TLR9-deficient mice (not shown).

Figure 3.

Cerebral microvascular leak and lesion in mice developing CM. Vascular leak as assessed macroscopically (A) by the blue discoloration of the brain of control WT, MyD88-deficient, and LT-α-deficient mice injected intravenously with 1% Evans blue on day 7 with severe CM or quantified after extravasation in formamide (C). Microvascular damage with mononuclear cell adhesion and perivascular hemorrhage (B) and ICAM-1 expression by immunohistochemistry on microvessels (D) in WT, MyD88-deficient, and LT-α-deficient mice. The data represent the mean ± SD of n = 5 mice per group pooled from two independent experiments (**P < 0.01); n.s., not significant. NI, noninfected.

The morphological correlate of the vascular leak was investigated in brain tissue sections at 7 days after infection. The brain vessels of infected WT mice displayed typical microvascular damage with mononuclear cell adhesion on the endothelium and hemorrhage into the parenchyma, which were also found in TLR9- and MyD88-deficient mice but absent in the CM-resistant LT-α-deficient strain (Figure 3B). The quantitative analysis of cerebral vascular permeability was in good agreement with the macroscopic observation, because Evans blue leakage was not significantly reduced in MyD88-deficient mice, as compared with WT mice, whereas it was essentially absent in LT-α-deficient mice (Figure 3C).

Further, we verified that CM was associated with an up-regulation of the intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in the absence of TLR. Indeed, ICAM-1 was up-regulated on vascular endothelium in the brain of TLR9- and MyD88-deficient mice as in WT mice on PbA infection (Figure 3D). We have previously shown that ICAM-1 expression is essential for CM development because ICAM-1-deficient mice are protected from the fatal neurological complication.12 Thus, the microvascular pathology associated with CM is independent of TLR9 and MyD88 pathways.

Acute Inflammation and Parasite Sequestration in the Lung

The microvascular pathology induced by PbA infection is not limited to the central nervous system but also involves pulmonary vessels, resulting in acute pulmonary inflammation. Therefore, we investigated lung sections to assess lung inflammation in PbA-infected TLR9- and MyD88-deficient mice. TLR9- and MyD88-deficient mice developed distinct inflammatory changes with thickening of the alveolar septae containing abundant intracapillary leukocytes similar to that seen in WT mice (Figure 4A). By contrast, CM-resistant LT-α-deficient mice show little inflammatory pathology in the lung, a finding that has not been reported before,8 except for a focal accumulation of mononuclear cells attributable to a homing defect.26 Quantification of the sequestered parasites in the lung was performed by flow cytometric analysis using GFP-transfected parasites.28 Analysis of lung homogenates revealed that parasite sequestration was not significantly reduced in MyD88 and LT-α-deficient mice (Figure 4B). Further, we assessed the vascular damage by Evans blue leakage in the bronchoalveolar space. WT and MyD88-deficient mice had high vascular permeability, whereas LT-α-deficient mice were primarily protected (Figure 4C). Therefore, acute lung inflammation after PbA infection, vascular leak, and parasite sequestration is TLR/MyD88 signaling-independent.

Figure 4.

Acute pulmonary inflammation, hemorrhage, and parasite sequestration in mice developing CM. A: Pulmonary inflammation, edema, and hemorrhage in the alveolar space was evaluated in H&E-stained microscopic sections of WT mice and those deficient for TLR9, MyD88, or LT-α 7 days after infection with 106 PbA-parasitized red blood cells. B: Parasite sequestration in the lung was analyzed by flow cytometry of WT, MyD88-deficient, and LT-α-deficient mice 7 days after infection with 106 enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-PbA parasitized red blood cells. C: Pulmonary vascular leak was quantified by lung Evans blue extravasation in formamide on day 7 with severe CM. The data represent the mean ± SD of n = 5 mice per group, from one of two independent experiments (**P < 0.01; n.s., not significant). NI, noninfected mice. Original magnifications, ×40.

Parasitemia and Hematological Changes Are Not TLR-Dependent

We then asked whether parasitemia and anemia are influenced in the absence of TLR signaling. Parasites are abundant in erythrocytes in the course of murine PbA infection and can be visualized by Giemsa staining of blood smear or by flow cytometry using GFP-transfected parasites.28 Parasitemia is usually low (less than 10%) when mice start to develop neurological signs leading to fatal CM. The absence of TLR and TLR adapters had no effect on parasitemia in all mice deficient for single or double TLR or for adapter proteins tested (Figure 5A). In contrast, CM-resistant LT-α-deficient mice, while presenting comparable parasitemia at day 7 (Figure 5A), developed extremely high parasitemia of ∼70% by day 22 (Figure 5B) consistent with published data.8

The hematological investigations at 7 days after infection revealed distinct reductions of thrombocytes in WT mice as compared with noninfected mice (Figure 5C) consistent with published data.31 This reduction was independent of TLR/MyD88 but was also found in the CM-resistant LT-α-deficient mice (Figure 5C). The latter finding suggests that thrombocytopenia in the blood in LT-α-deficient mice is not an indicator of platelet sequestration in microvessels.3 The total white blood cell counts decreased after infection in WT mice (Figure 5D), primarily attributed to a decrease in lymphocytes (Figure 5E), whereas neutrophil counts were augmented (Figure 5F). Similar changes were found in TLR- and MyD88-deficient mice, whereas LT-α-deficient mice behaved as noninfected control.

Finally, no significant anemia developed 7 days after infection, and the erythrocyte count was still in the normal range (Figure 5G) as well as the hematocrit and hemoglobin concentrations (data not shown). The CM-resistant LT-α-deficient mice developed dramatic anemia (1.34 ± 0.30 × 106 on day 22) and probably succumbed of general hypoxia after 3 weeks. Thus, parasitemia, thrombocytopenia, neutrophilia, and lymphopenia after PbA infection developed in the absence TLR/MyD88 signaling.

Parasite Sequestration and Pigment Deposition in the Liver

PbA infection is associated with abundant hemozoin-like pigment deposition in Kupffer cells with focal accumulation of mononuclear cells and single cell necrosis. These changes are nonspecific because of sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes in TLR9- and MyD88-deficient and control WT mice at day 7, as well as in LT-α-deficient mice (Figure 6A). Further, a progressive deposition of pigment with chronic inflammation and minor hepatocyte degeneration at later stages was observed in the CM-resistant LT-α-deficient mice (data not shown). This, however, was not as prominent as found after infection with the P. berghei NK65 strain, which causes MyD88-dependent liver damage.32 The accumulation of malaria pigment and mononuclear cells was TLR-independent. The amount of sequestered parasites was then analyzed in liver homogenates. The results suggest that parasite sequestration in the liver is TLR/MyD88-independent (Figure 6B). In conclusion, PbA, unlike the NK65 strain, does not cause prominent liver damage, and the deposition of malaria pigment and parasite sequestration were independent of TLR and MyD88 signaling.

Figure 6.

Hepatic parasite sequestration and hemoglobin-derived pigment deposition is TLR-independent. A: Microscopic analysis of liver sections from control WT and MyD88- and TLR9-deficient mice at day 7 of infection, H&E staining. B: Sequestration of GFP-labeled parasites in the liver by flow cytometry analysis of liver homogenates. The data represent the mean ± SD of n = 5 mice per group from two independent experiments (NI, noninfected; n.s., not significant). Original magnifications, ×40.

Discussion

The role of the innate immune Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in the development of malaria, and in particular of fatal microvascular disease in the brain, known as CM, was unknown. Recent investigations at the molecular level proposed that hemozoin and GPI expressed by P. falciparum might represent novel TLR9 and TLR2–4 ligands activating the innate immune system.11,12 However, the relation between TLR activation by malarial products and the development of CM is not established.

Here, using blood stage infection we demonstrate that TLR9 signaling is not required for the PbA-induced neurological syndrome known as CM with limb paralysis, ataxia, and coma because TLR9-deficient mice succumbed to CM within 6 to 8 days. Testing mice deficient for several members of the TLR family (TLR1, -2, -3, -4, -6, -7, and -9), including the major TLR adaptor proteins MyD88, TIRAP, and TRIF, we conclude here for the first time that TLR signaling is dispensable for the development of fatal CM. Although our data do not exclude the possibility that malarial molecular motifs may activate the innate immune system, TLR-dependent activation of innate immunity is unlikely to contribute significantly to the proinflammatory response to PbA infection.

We investigated several pathophysiological aspects of CM in TLR-deficient mice and show that TLR-deficient mice develop typical microvascular damage with accumulation of mononuclear cells, vascular leak, hemorrhage, and inflammation in the brain. Further, TLR-deficient mice display pulmonary microvascular damage with alveolitis and plasma and erythrocyte leak in the alveolar space as control mice. Therefore, PbA-induced microvascular damage in both lungs and brain is TLR signaling-independent.

The hematological investigations in TLR-deficient mice were comparable with those obtained in control WT mice showing thrombocytopenia, decreased lymphocyte counts, and augmented neutrophil counts at day 7 when the mice commence developing CM in the absence of anemia and low parasitemia as observed before.5 Therefore, disruption of TLR signaling has no effect on the typical inflammatory response to PbA infection in mice.

Last, liver pathology is not an important feature of PbA infection. At day 7 when mice succumb to CM, there is no significant hepatic pathology. This is in contradistinction with P. berghei NK65 strain, which causes overt liver injury in a MyD88-dependent manner32 and which is not a feature of PbA infection. LT-α-deficient mice used here served as controls, which do not develop fatal CM development on PbA infection.8 Under the experimental conditions in the study, we confirm the published data. Further, we demonstrate that the absence of LT-α abrogates the cerebral and pulmonary microvascular disease and inflammation. The interpretation of the effects of the infection on blood leukocytes is compounded by the fact that LT-α-deficient mice have a leukocyte homing defect.26

Therefore, our data clearly demonstrate that TLR9, other TLR family members, and TLR adaptor proteins MyD88, TIRAP, and TRIF are dispensable for the development of fatal CM in vivo. These results were not predicted by the TLR agonistic data reported on activation of TLR9 and TLR2–4 by hemozoin and GPI expressed by P. falciparum.11,12 However, those investigations were focusing on in vitro or short-term in vivo innate immune activation. We confirm that parasitized erythrocytes activate antigen-presenting cells. The lack of correlation of early innate immune parameters with disease outcome has its precedent in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection. In fact, although TLR-deficient macrophages and dendritic cells have a blunted proinflammatory response to Mtb, the control of Mtb infection in vivo was primarily TLR-independent.33

Recent investigations demonstrated a potential for innate immune mechanisms directed against the Plasmodium parasites to contribute to pathology and protection from malaria.34 Several cell types such as dendritic cells, macrophages, γδ T, NK, and natural killer T cells contribute to the innate response.35 Both human and murine dendritic cells are activated by blood stage parasites in a TLR9-dependent manner,36 which is possibly mediated by hemozoin derived from the human parasites.11 NK cells are an important source of IFN-γ, and disruption of IFN-γ signaling or NK cell depletion leads to increased parasitemia and higher mortality in mouse models of malaria.6,35 We have recently shown that macrophage-derived IL-18 is required for NK cell activation by P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes resulting in IFN-γ production, which depends on IL18R/MyD88 signaling on both macrophages and NK cells.15 However, TLR signaling of NK cells is dispensable for their activation.15

Last, we investigated the role of the CD14 and IL-1, which both are part of the TLR/MyD88 signaling pathways. CD14 may associate with TLR2, TLR4, and TLR337 acting as a match maker of the TLR pathway30; however, CD14-deficient mice developed fatal CM in response to PbA infection. The potential participation of IL-1, a critical mediator in inflammation,38 was excluded because IL-1R1-deficient mice were as sensitive to PbA-induced CM as WT controls (data not shown). The clinical relevance of the findings in mice are being tested by TLR gene polymorphism analyses suggesting an association of TLR4 and TLR9 variants with susceptibility and severity of malaria39; however, more investigations are necessary to strengthen a link between disease manifestation and TLR polymorphism.

In conclusion, the present data demonstrate that TLR sensing or signaling of PbA-parasitized erythrocytes does not contribute to microvascular disease resulting in fatal CM.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Bernhard Ryffel, UMR6218, IEM, CNRS Transgenose Institute, 45071 Orleans, France. E-mail: bryffel@cnrs-orleans.fr.

Supported by Le Studium (Orleans, France); the Medical Research Foundation (FRM), Orleans, France; the Biomedical Research Foundation SBF, Matzingen, Switzerland; the European FP6 MPCM (no. 037749) project, and the French Ministère de l’Education National de la Recherche et de la Technologie.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on see http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2005;434:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature03342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J, Lucas R, Grau GE. Pathogenesis of cerebral malaria: recent experimental data and possible applications for humans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:810–820. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.810-820.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield L, Grau GE. Immunological processes in malaria pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:722–735. doi: 10.1038/nri1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau GE, Fajardo LF, Piguet PF, Allet B, Lambert PH, Vassalli P. Tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) as an essential mediator in murine cerebral malaria. Science. 1987;237:1210–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.3306918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin W, Eugster HP, Bordmann G, Bonato J, Muller M, Yamage M, Ryffel B. Resistance to cerebral malaria in tumor necrosis factor-alpha/beta-deficient mice is associated with a reduction of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 up-regulation and T helper type 1 response. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:257–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amani V, Vigario AM, Belnoue E, Marussig M, Fonseca L, Mazier D, Renia L. Involvement of IFN-gamma receptor-medicated signaling in pathology and anti-malarial immunity induced by Plasmodium berghei infection. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1646–1655. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1646::AID-IMMU1646>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre N, Da Laperousaz C, Ryffel B, Weiss NA, Imhof BA, Rudin W, Lucas R, Piguet PF. Role of ICAM-1 (CD54) in the development of murine cerebral malaria. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:961–968. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engwerda CR, Mynott TL, Sawhney S, De Souza JB, Bickle QD, Kaye PM. Locally up-regulated lymphotoxin alpha, not systemic tumor necrosis factor alpha, is the principle mediator of murine cerebral malaria. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1371–1377. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S. Mammalian Toll-like receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:5–11. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Jiang Z, Georgel P, Crozat K, Croker B, Rutschmann S, Du X, Hoebe K. Genetic analysis of host resistance: Toll-like receptor signaling and immunity at large. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:353–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coban C, Ishii KJ, Kawai T, Hemmi H, Sato S, Uematsu S, Yamamoto M, Takeuchi O, Itagaki S, Kumar N, Horii T, Akira S. Toll-like receptor 9 mediates innate immune activation by the malaria pigment hemozoin. J Exp Med. 2005;201:19–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnegowda G, Hajjar AM, Zhu J, Douglass EJ, Uematsu S, Akira S, Woods AS, Gowda DC. Induction of proinflammatory responses in macrophages by the glycosylphosphatidylinositols of Plasmodium falciparum: cell signaling receptors, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) structural requirement, and regulation of GPI activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8606–8616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413541200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebl T, De Veer MJ, Schofield L. Stimulation of innate immune responses by malarial glycosylphosphatidylinositol via pattern recognition receptors. Parasitology. 2005;130:S45–S62. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield L, Hewitt MC, Evans K, Siomos MA, Seeberger PH. Synthetic GPI as a candidate anti-toxic vaccine in a model of malaria. Nature. 2002;418:785–789. doi: 10.1038/nature00937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baratin M, Roetynck S, Lepolard C, Falk C, Sawadogo S, Uematsu S, Akira S, Ryffel B, Tiraby JG, Alexopoulou L, Kirschning CJ, Gysin J, Vivier E, Ugolini S. Natural killer cell and macrophage cooperation in MyD88-dependent innate responses to Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14747–14752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507355102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Sato S, Horiuchi T, Hoshino K, Takeda K, Dong Z, Modlin RL, Akira S. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins. J Immunol. 2002;169:10–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen KS, Aicher A, Mohaupt M, Hartung T, Dimmeler S, Kirschning CJ, Schumann RR. The role of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in bacteria-induced maturation of murine dendritic cells (DCS). Peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid are inducers of DC maturation and require TLR2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25680–25686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Muhlradt PF, Morr M, Radolf JD, Zychlinsky A, Takeda K, Akira S. Discrimination of bacterial lipoproteins by Toll-like receptor 6. Int Immunol. 2001;13:933–940. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Sanjo H, Hoshino K, Horiuchi T, Tomizawa H, Takeda K, Akira S. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K, Wagner H, Takeda K, Akira S. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R. The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signalling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;420:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature01180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, Janssen E, Tabeta K, Kim SO, Goode J, Lin P, Mann N, Mudd S, Crozat K, Sovath S, Han J, Beutler B. Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling. Nature. 2003;424:743–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks TA, Rouse BT, Kerley MK, Blair PJ, Godfrey VL, Kuklin NA, Bouley DM, Thomas J, Kanangat S, Mucenski ML. Lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient mice. Effects on secondary lymphoid organ development and humoral immune responsiveness. J Immunol. 1995;155:1685–1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang KK, Dorner BG, Merkel U, Ryffel B, Schutt C, Golenbock D, Freeman MW, Jack RS. Neutrophil influx in response to a peritoneal infection with Salmonella is delayed in lipopolysaccharide-binding protein or CD14-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:4475–4480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke-Fayard B, Janse CJ, Cunha-Rodrigues M, Ramesar J, Buscher P, Que I, Lowik C, Voshol PJ, den Boer MA, van Duinen SG, Febbraio M, Mota MM, Waters AP. Murine malaria parasite sequestration: CD36 is the major receptor, but cerebral pathology is unlinked to sequestration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11468–11473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503386102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Eugster HP, Le Hir M, Shakhov A, Di Padova F, Maurer C, Quesniaux VF, Ryffel B. Correction or transfer of immunodeficiency due to TNF-LT alpha deletion by bone marrow transplantation. Mol Med. 1996;2:247–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finberg RW, Wang JP, Kurt-Jones EA. Toll-like receptors and viruses. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:35–43. doi: 10.1002/rmv.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau GE, Piguet PF, Gretener D, Vesin C, Lambert PH. Immunopathology of thrombocytopenia in experimental malaria. Immunology. 1988;65:501–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K, Tsutsui H, Kashiwamura S, Seki E, Nakano H, Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Okumura K, Van Kaer L, Okamura H, Akira S, Nakanishi K. Plasmodium berghei infection in mice induces liver injury by an IL-12- and Toll-like receptor/myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2001;167:5928–5934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryffel B, Fremond C, Jacobs M, Parida S, Botha T, Schnyder B, Quesniaux V. Innate immunity to mycobacterial infection in mice: critical role for Toll-like receptors. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005;85:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall N, Carlton J. Comparative genomics of malaria parasites. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson MM, Riley EM. Innate immunity to malaria. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:169–180. doi: 10.1038/nri1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichyangkul S, Gettayacamin M, Miller RS, Lyon JA, Angov E, Tongtawe P, Ruble DL, Heppner DG, Jr, Kester KE, Ballou WR, Diggs CL, Voss G, Cohen JD, Walsh DS. Pre-clinical evaluation of the malaria vaccine candidate P. falciparum MSP1(42) formulated with novel adjuvants or with alum. Vaccine. 2004;22:3831–3840. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Dunzendorfer S, Soldau K, Tobias PS. Double-stranded RNA-mediated TLR3 activation is enhanced by CD14. Immunity. 2006;24:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamero AM, Oppenheim JJ. IL-1 can act as number one. Immunity. 2006;24:16–17. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockenhaupt FP, Bedu-Addo G, Junge C, Hommerich L, Eggelte TA, Bienzle U. Markers of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistant falciparum malaria in placenta and circulation of pregnant women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:332–334. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00856-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.