The first-ever U.S. Surgeon General’s report on oral health, released in May 2000, addressed the growing disparity between groups who have optimum oral health and groups who do not. 1 The report termed oral health “a mirror for general health and well-being,” citing links between oral health and other health problems. A report from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) followed in 2001, titled “A Plan to Eliminate Craniofacial, Oral, and Dental Health Disparities.” It is an action plan, targeting disparities that result from differences in culture, language, diet, physical activity, socioeconomic and demographic status, gender, age, environmental pollutants and occupational hazards.2 The Surgeon General, in a separate report in 2003, called for a national partnership to improve and maintain the nation’s oral health. 3

According to one author, there is growing consensus among health researchers that they have a responsibility both to acquire scientific knowledge and also to apply it in a way that benefits the public health. 4 An extension of that argument is that dental scientists and educators cannot say they are committed to improving oral health and then not accept the task of disseminating the results of research to the community. In the past the results of research have failed to reach those studied and facing health disparities. However, results oriented community-based research requires greater efforts to establish and maintain networks and trust. Developing readiness in a community to sanction and participate in research takes time. Funding for such research requires flexibility5 and universities must provide incentives for faculty to apply their research findings to reduce disparities. 6

In 2001 NIDCR responded to the Surgeon General’s landmark report and the greater need to support community-based research by funding five regional Centers for Research to Reduce Oral Health Disparities and committing $7 million per year over a seven-year period for support to each of these centers. The Centers were identified after an exhaustive national competition. The Centers are based at Boston University, New York University, University of California, San Francisco, University of Michigan, and University of Washington. Reflecting the importance of research to reduce disparities, the expenditures for the Centers, along with related grants and programs, encompass the single largest commitment ever made by the NIDCR. An important part of each center’s mission is opening career development opportunities for potential scientists from underrepresented groups—the same groups the Surgeon General targeted for study and treatment.

The Centers are sponsored in part by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHHD) at NIH. In response to a question about why NCMHHD was sponsoring oral health research, Dr. John Ruffin, director of the Center, responded: “…we are pleased to help support these centers through this promising interdisciplinary effort with the NIDCR. This partnership…demonstrates how we can work together with our communities to build the collaborative biomedical and behavioral research enterprise we need to eliminate health disparities.”

The purpose of this report is to describe on-going and planned research at the five centers and to suggest how the results of this health disparities research may impact dental practitioners and their communities. The report also demonstrates the extent of commitment of university-based investigators to the needs of underserved communities and the importance of treating our communities as true partners in research.

THE CENTERS

The regional centers funded by NIDCR are as diverse in their goals and natures as the people and problems they address. 7 Each center has identified target populations and research focuses on different geographical area. For example, the primary goal at the University of California, San Francisco center is to conduct research aimed at preventing early childhood caries (ECC) in low socioeconomic groups and ethnic/racial minorities, while researchers at New York University are working to cut the rate of oral cancers in adolescent and adult males. Each of the five centers has forged partnerships that include ties with component dental societies, state and local health agencies, community and migrant health centers, Native American tribal nations and institutions that serve other diverse patient populations.

Center to Address Disparities in Children’s Oral Health (CAN-DO) at the University of California, San Francisco

The CAN-DO program operates through a network of community organizations. Researchers from the center work directly with departments of public health and other California social and health-care agencies. 8 CAN-DO focuses on preventing ECC among Mexican-, African-, Chinese-, and Filipino-American populations as well as among children from low-income families. The severity of the problem in California is illustrated by the differential prevalence of ECC determined in a statewide survey. Among preschool children statewide, 14% were found to have ECC. This prevalence was much higher among some population groups, 44% among Asian and 39% among Latino children from low-income families enrolled in Head Start programs. 9 The CAN-DO center works from two directions-from past to present and from present to future-to delineate the problems and find ways to ameliorate them. From the past, researchers collect data to reveal factors associated with dental inequalities. Looking to the future, they use the data to predict which groups of children are most likely to be susceptible to dental disease that can be targeted for interventions. Clinical trials are being conducted to determine which treatments might be most effective.

Here are two examples of the several programs and research studies the CAN-DO center has sponsored:

An infant oral health care program is providing information on preventing dental caries in children to the families enrolled in this study at the San Ysidro Community Health Center near the US-Mexican border. All the pregnant women participating in this randomized clinical trial receive counseling before and after delivery. New mothers in the intervention group receive chlorhexidine mouthrinse to prevent transmission of cariogenic bacteria from mother to child, and infants, once their teeth erupt, receive applications of fluoride varnish to prevent dental caries.

In another study, focus groups have been conducted in English and other languages to determine if cultural factors affect access to preventive oral health care for young children. The community participants are African-American, Chinese, Filipino and Hispanic caregivers of children 1 and 5 years old, both US born and non-US born. Little information is known about oral health beliefs and practices for many specific race/ethnic groups and cultures in the U.S. Researchers plan to use the results of this study to develop culturally appropriate programs and interventions. Collaborators with UCSF are the San Francisco Department of Public Health, the San Ysidro Community Health Center (located near the U.S.-Mexican border) and 12 other agencies and institutions along the West Coast. The projects include considerable community participation in design, implementation and interpretation of findings.

Research on Adolescent and Adult Health Promotion: New York University Oral Cancer RAAHP Center

Unlike the other centers, which seek to reduce dental disparities among young children, this center concentrates its research on adolescents and adults—specifically on oral cancer in these groups. 10 The NYU RAAHP Center, which includes 12 collaborating universities and health agencies, is conducting epidemiologic and health promotion studies focused on reducing the incidence and mortality of oral cancer, including the following:

A study on environmental and genetic risk factors for oral epithelial dysplasia in Puerto Rico. The primary aim of this study is to estimate the association between OED and the use of smoking tobacco and alcoholic beverages, as well as nutritional factors, in a Hispanic population living in Puerto Rico.

The first study comparing the five oral cancer detection methods currently available for use by the general dentists against the “gold standard” of surgical biopsy regarding validity of diagnosis. It is expected that insights gained from this study will leading to new ideas about biomarkers for oral cancer and their exploitation for the prevention, early detection and treatment of oral cancer.

A dental practice-based smoking cessation randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing a technique called “personalized risk feedback” with more traditional educational interventions on inner-city adolescent and adult populations. .

A questionnaire survey to determine whether, and if so—why—minorities’ participation in cancer screenings, and as research participants, differ from that of Whites using a random digit dial telephone technique to 1800 participants in New York City, Baltimore and San Juan.

To strengthen the future base of researchers on issues of minority health and health disparities, the NYU center has begun research training with minority faculty and dental students at the University of Puerto Rico, Howard University and Tuskegee University. Additionally, the NYU Oral Cancer RAAHP Center has partnered with Tuskegee University’s National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care in establishing a national bioethics research competition for pilot studies funded by the NYU Oral Cancer RAAHP Center for studies relevant to cancer research and care.

If successful, the NYU Oral Cancer RAAHP Center research will produce model strategies for the reducing the burden of oral cancer in minority and under served communities and can be applied widely. It will also have provided opportunities for students and minority faculty from partnering schools to gain skills and assert greater control over the health of their own communities.

Northeast Center for Research to Evaluate and Eliminate Dental Disparities

The CREEDD (as in “we believe”) is based at Boston University School of Dental Medicine and is a collaborative effort involving Boston Medical Center, the Boston Public Health Commission, Forsyth Institute, and other institutions in the Boston area and New England. 11 It also has projects based at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., and the Columbus Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

The CREEDD’s underlying research hypothesis is that “oral health matters” - oral conditions are importantly related to functional well-being and to systemic health outcomes. The main research focus is ECC, which remains a major unmet health need in the communities that the Boston center has targeted, disproportionately affecting poor children and those from minority racial and ethnic groups. A key Center goal is to quantify the effects oral conditions on the health-related quality of life of low-income and minority children, adolescents, and their families, using valid and reliable short-form questionnaires being developed by Center investigators.

Essential to the CREEDD’s research objectives is its Community Liaison Core, building on its experience in creating and implementing model prevention programs and in effecting their transfer to new settings beyond the Boston metropolitan area. Investigators are also studying the best ways to involve physicians in oral health promotion. One research project in this area is examining the use of patient-centered counseling, by pediatricians and nurses, with the goal of reducing caries risk in very young children.

In work led by investigators at Children’s National Medical Center and Columbus Children’s Hospital, one project aims to determine whether severe dentoalveolar infection in young children can slow their growth and whether such effects are mediated by nutritional factors. The Center is also conducting microbiological studies of children and caregivers from various racial and ethnic groups in order to identify the microbes that may cause oral diseases and how these microbes may be acquired.

The CREEDD is also working to enhance the research pipeline by providing training opportunities for talented high school, college, and dental students, in addition to training doctoral and postdoctoral investigators. Support for trainees has come from NIDCR research training grant and minority research supplement programs. The CREEDD expects that its research, training, and outreach programs will result in measurable improvements in the oral health status of its target populations. To assess its effectiveness in meeting such outcomes, the Center is being guided by the oral health goals and objectives of Healthy People 2010.

Detroit Center for Research on Oral Health Disparities at the University of Michigan

Detroit inner city families face many circumstances similar to those of families in other inner cities in the United States: deteriorating housing, high unemployment, limited health care resources, large numbers of uninsured individuals, a faltering school system, disproportionate rates of adult men in prison and a crumbling safety net.

Researchers report that when they observe the obstacles inner-city families face in their daily lives, it is impossible to isolate their oral health status from the rest of their lives. This team of researchers is seeking to learn why some families have good oral health and others do not, even when they live in the same neighborhoods and share similar racial, economic and social environments. Researchers look beyond traditional oral health status indicators to examine and attempt to understand oral health disparities in communities that face difficult social, economic, and environmental challenge.

The Center has brought together researchers from the University of Michigan’s Schools of Dentistry, Public Health, Social Work, Nursing, and Institute for Social Research, as well as community partners Detroit Department of Health and Voices of Detroit Initiative. 12

The University of Michigan center has a unique focus because most of its research programs concentrate on a single population group: African-American children under 6 years old and their main caregivers, who live in low-income neighborhoods in Detroit. More than a thousand families participate in the Detroit Dental Health Project. Participants will be monitored for at least four years. The Center incorporates a strong service component, which researchers believe is important to their goals and to the community at large. In addition to the Detroit inner-city focus, the Center funds a project to evaluate a unique “real-life experiment” in Michigan in which Medicaid recipients are covered in a system equivalent to private dental insurance.

Using survey research and clinical examinations, the research team is examining a number of possible determinants that can affect oral health outcomes in children and their caregivers. Variables include stress, parenting styles, diet and nutrition, lead exposure, racial discrimination, stress and depression, degree of social support and access to services, racial discrimination, housing instability, employment, religious views and practices, cultural beliefs and oral hygiene practices. Center dentists have conducted examinations for early and advanced signs of dental caries, periodontal disease and oral cancer. Other team members have undertaken extensive “asset mapping” of the neighborhoods to better understand how a community’s physical assets may affect oral health. The information that was collected in 2002 and 2003 from 1,023 families will be used to design tailored interventions to reduce oral health disparities. The team is now working on design an evidence-based realistic educational program to promote oral health of young children. The program will be implemented and evaluated starting in 2004. Should the intervention be successful, the process and strategies used can be a model for other communities.

Northwest/Alaska Center to Reduce Oral Health Disparities at the University of Washington

The Seattle target groups are unique and diverse. They include Alaska Natives, Native Americans, Hispanic migrant farm workers, African-American and Hispanic families from local military bases, Pacific Islanders and low-income rural Caucasians. 13

The diversity of the targeted populations requires Washington researchers to translate dental knowledge and techniques into means of care that will work in culturally appropriate and effective ways. Here are some key facts about the populations with whom the Northwest/Alaska center works:

57 percent of native children in Alaska have dental caries by age 3. Ninety-eight percent of their mothers have dental caries. 14

Children in Washington have a relatively high rate of dental caries compared to children in other states. More than half of Hispanic children in Washington have dental caries. 15

Center researchers from the UW schools of Medicine and Dentistry are conducting a clinical trial with young Native Alaskan mothers as participants to determine whether two weeks of chlorhexidine mouth rinses followed by two years of chewing xylitol gum will prevent dental caries in the children of these mothers. The mothers also receive dental care and oral hygiene instruction. If results show better oral health in the test group, researchers predict the chlorhexidine-xylitol regimen could result in a change in the standard of dental care for this population. As part of the Center’s commitment to this native community, researchers are providing continuing education for health care providers and working to identify other ways that findings can be used. Results could also reinforce a movement to modify insurance programs and Medicaid to more adequately cover mothers. Other Center research focuses on the development of vehicles for xylitol that are acceptable to children and their parents. One project has developed xylitol containing gummy bears and other snack foods that can be used in community Head Start classroooms.

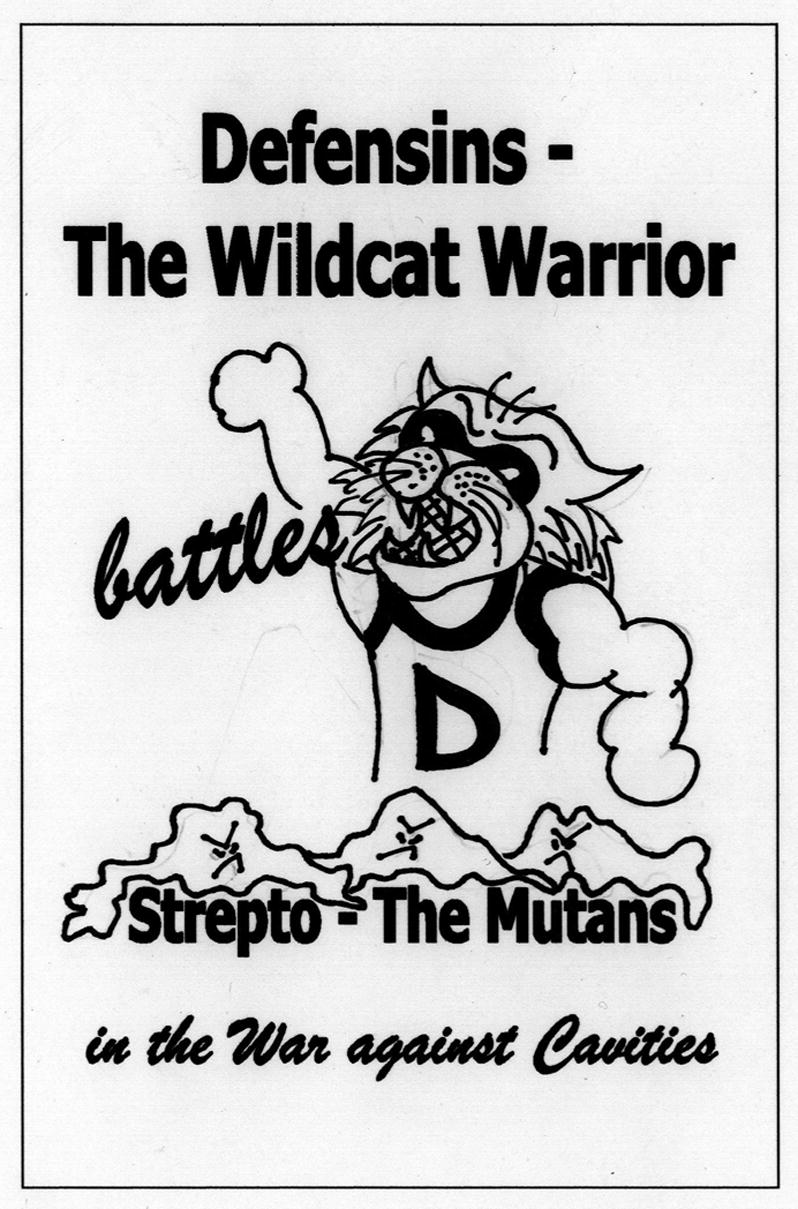

Other Center researchers are testing the hypothesis that natural antibodies in epithelial cells lining the mouth protect against dental caries. Their participants are Hispanic children in the Yakima Valley of eastern Washington. Staff from the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic and students from Heritage College in Toppenish, WA are collaborating. If tests bear out their hypothesis, researchers will work with caries-prone children to determine whether these participants experience a breakdown in antibody protection. This project is of special note because it was the first experience of a senior bench scientist to conduct research in a community setting and to be responsible for providing direct benefits to the children and the schools that participated. 16

Another group at the Washington based center is testing streamlined interceptive orthodontic treatment for children from low-income families during transitional dentition. This study is under way in Seattle’s inner city with a focus on African-American and African immigrant children. The investigators hypothesize that most of these children will not need regular orthodontic treatment after this relatively inexpensive intervention. Further, the treatment methods may be taught to pediatric dentists and general practitioners, who might then work in collaboration with orthodontists to reduce oral health disparities.

In a pilot project, a general dentist serving a rural Hispanic population is developing a secure web site to share records with orthodontists in Seattle in order to get advice about how to treat his rural patients lacking access to orthodontic care.

Conclusion

In developing this national network of oral health disparity research centers, the National Institutes of Health is attempting to address the needs of communities with poor oral health. Many of these communities that are the focus of center investigators rarely participate in research and do not trust outside investigators. Previously, many researchers conducted research but left nothing behind and often failed to disseminate the results of the research or provide any benefit to those that participated. Such practice was due to different priorities and perspectives of researchers in the past as well as the result of lack of an initiative and funding to implement the findings to benefit the community studied. As a result, community members, who are far removed from the bureaucracy of research funding, ended up feeling that they were being used as “guinea pigs”. Hence, a major part of the effort of these new oral health research centers is to build community networks and establish long-term relationships. Center investigators also recognize that solutions to these vexing problems must be built on an understanding of the social, economics, racial, educational, political and behavioral factors that impact most health care problems.

Collectively, the centers at these five universities and their community partners will contribute new model strategies and understanding of oral health disparities that can be applied with communities throughout the United States.

SIDEBARS

The agencies behind the National Centers for Research on Oral Health Disparities.

-The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, or NIDCR: This is the federal focal point for oral health research within the National Institutes of Health. Its Web site is at “www.nidcr.nih.gov”.

-

-National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities: This agency is partner with NIDCR centers and other initiatives. It’s goal is long, healthy and productive lives for all populations. Its Web site is at “www.ncmhd.nih.gov”.

Diversity and the Future of Patient Care

-Today, nearly one out of every 10 U.S. residents is foreign-born. The majority of these new Americans are of Hispanic or Asian/Pacific Islander origin.

-More than one of every four Americans today is African-American, Hispanic or Asian/non-Hispanic. By 2020, that proportion will increase to one of every three Americans, and by 2050, racial and ethnic “minority” groups are expected to be the majority.

-Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians/Alaska Natives have the poorest oral health of any population groups in the United States.

Figure 1.

Directors of the Oral Health Disparity Centers OF THE National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, or NIDCR (from left to right): Dr. Raul Garcia, Boston University; Dr. Jane Weintraub, University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Amid Ismail, University of Michigan; Dr. Ruth Nowjack-Raymer, NIDCR project officer; Dr. Ralph Katz, New York University; and Dr. Peter Milgrom, University of Washington.

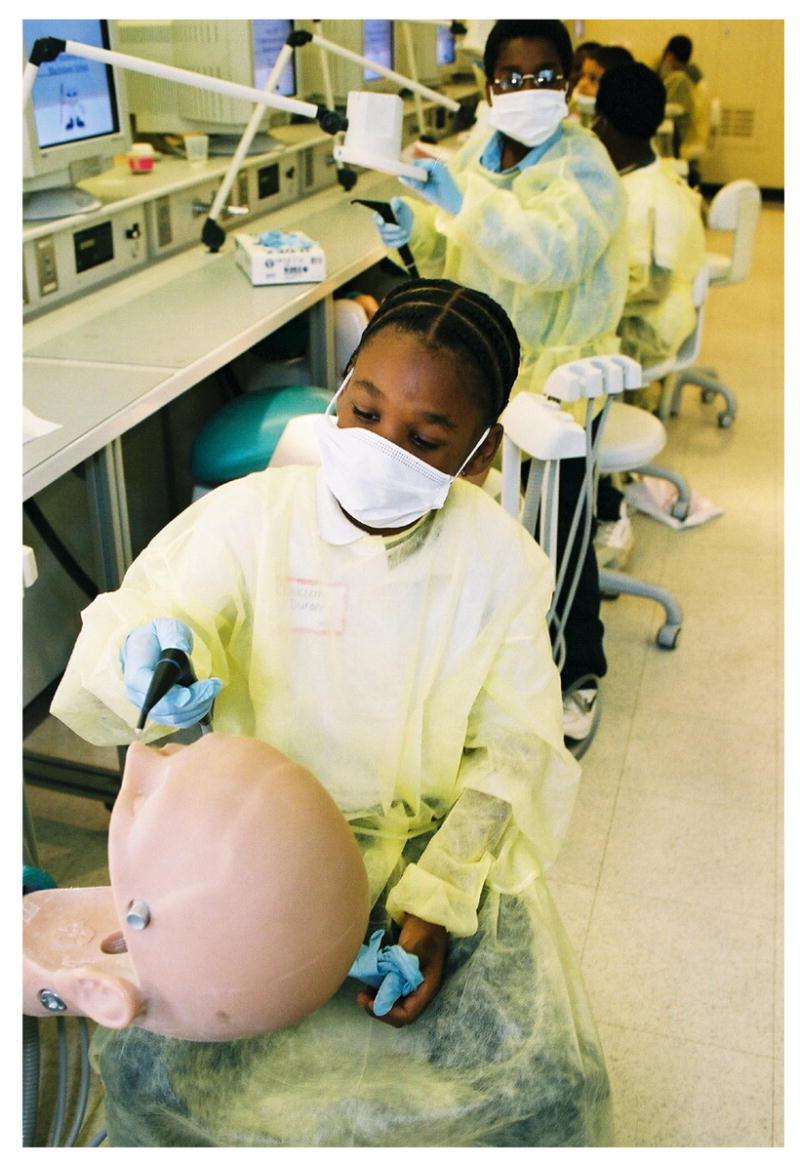

Figure 2.

Third-graders from Boston’s Blackstone school, a Center for Research to Evaluate and Eliminate Dental Disparities site, on their annual “day as dental students” field trip to Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine. More than 97 percent of Blackstone schoolchildren are minorities.

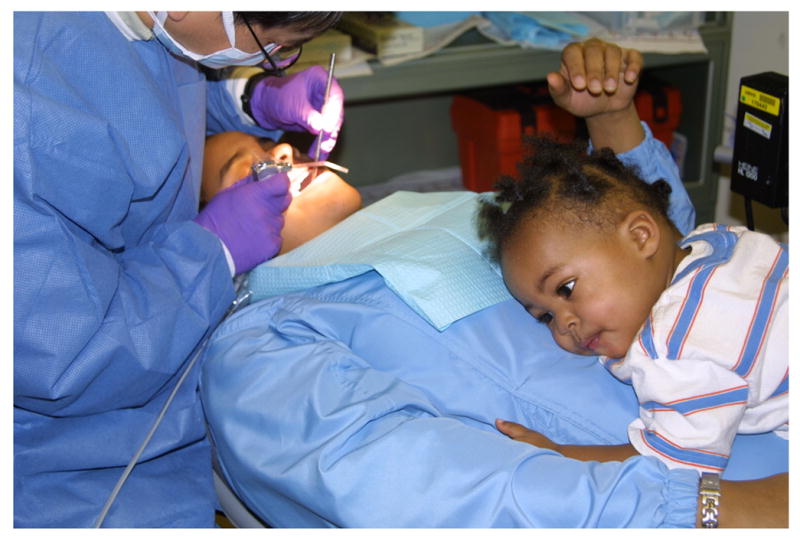

Figure 3.

A caregiver and her daughter being examined by a dentist at the Detroit Dental Assessment Center, the office of the Detroit Center for Research on Oral Health Disparities.

Figure 4.

“Oral Science” is a comic book developed for middle-school students participating in basic research about oral beta-defensins in the Yakima Valley, Washington. The research is part of the University of Washington program. The cover was drawn by Pat Brown and the University of Washington Oral Health Collaborative.

Figure 5.

The San Ysidro Health Center in California near the U.S.-Mexican border: site of a major University of California, San Francisco oral health disparities research program to prevent early childhood caries.

Footnotes

The Centers for Research to Reduce Oral Health Disparities are supported, in part, by grants U54 DE 014264, DE 014261, DE 014257, DE 014402, DE 014254 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

Contributor Information

Peter Milgrom, Dr. Milgrom is professor, Department of Dental Public Health Sciences, and the director, Northwest/Alaska Center to Reduce Oral Health Disparities, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Box 357475, Seattle, Wash. 98195-7475, email dfrc@u.washington.edu.

Raul I. Garcia, Dr. Garcia is a professor and the chair, Department of Health Policy and Health Services Research, Goldman School of Dental Medicine, Boston University, and director, Center for Research to Evaluate and Eliminate Dental Disparities, Boston..

Amid Ismail, Dr. Ismail is a professor, Department of Cariology, Restorative Sciences, and Endodontics, School of Dentistry, and the Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He also is director of the Detroit Center for Research on Oral Health Disparities..

Ralph V. Katz, Dr. Katz is a professor and the chair, Department of Epidemiology and Health Promotion, and the director, New York University Oral Cancer Research on Adolescent and Adult Health Promotion Center at the New York University College of Dentistry College of Dentistry..

Jane A. Weintraub, Dr. Weintraub is Lee Hysan professor and chair, Division of Oral Epidemiology and Dental Public Health, Department of Preventive and Restorative Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of California, San Francisco. She also is director, Center to Address Disparities in Children’s Oral Health, San Francisco..

References

- 1.U.S. Surgeon General. [Accessed October 12, 2003.];Report of the Surgeon General. Oral health in America. URL: http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sgr/oralhealth.asp.

- 2.NIDCR, NIH. [Accessed October 12, 2003];A plan to eliminate craniofacial, oral, and dental health disparities. URL: http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/health_disp.asp.

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIH Publication No. 03-5303, Spring 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weed DL, McKeown RE. Science and social responsibility in public health. Environ Health Perspect. 2003 Nov;:111–14. 1804–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003 Aug;:93–8. 1210–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyden P. Academic incentives for faculty participation in community-based participatory research. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Jul;18(7):576–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NIH News Release. [Accessed October 12, 2003];NIDCR funds centers to reduce oral health disparities. http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/oct2001/nidcr-01.htm.

- 8.University of California, San Francisco. [Accessed November 16, 2003.];The Center to Address Disparities in Children’s Oral Health. URL: http://www.ucsf.edu/cando/

- 9.Pollick HF, Pawson IG, Martorell R, Mendoza FS. The estimated cost of treating unmet dental restorative needs of Mexican-American children from Southwestern US HHANES, 1982–83. J Public Health Dent. 1991 Fall;51(4):195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1991.tb02215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New York University College of Dentistry. [Access November 16, 2003.]; URL: http://www.nyu.edu/dental/raahp/index.html.

- 11.Northeast Center for Research to Evaluate and Eliminate Dental Disparities. [Accessed December 6, 2003.]; URL: http://www.creedd.org/

- 12.Detroit Center for Research on Oral Health Disparities. [Accessed November 16, 2003.]; URL: http://oralhealth.dent.umich.edu/dcrohd.html.

- 13.University of Washington. [Accessed November 16, 2003]; URL: http://depts.washington.edu/nacrohd/about.htm.

- 14.Lewis CW, Riedy CA, Grossman DC, Domoto PK, Roberts MC. Oral health of young Alaska Native children and their caregivers in Southwestern Alaska. Alaska Med. 2002 Oct–Dec;44(4):83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leroux BG, Maynard RJ, Domoto P, Zhu C, Milgrom P. The estimation of caries prevalence in small areas. J Dent Res. 1996;75(12):1947–56. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750120601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dale BA, Brown PS, Wells NJ. Picture talk-effective communication with participants as a critical element in oral health research. J Dent Res. 2003 Sep;82(9):669–70. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]