Abstract

How the events of mitosis are coordinated is not well understood. Intriguing mitotic regulators include the chromosomal passenger proteins. Loss of either of the passengers inner centromere protein (INCENP) or the Aurora B kinase results in chromosome segregation defects and failures in cytokinesis. Furthermore, INCENP and Aurora B have identical localization patterns during mitosis and directly bind each other in vitro. These results led to the hypothesis that INCENP is a direct substrate of Aurora B. Here we show that the Caenorhabditis elegans Aurora B kinase AIR-2 specifically phosphorylated the C. elegans INCENP ICP-1 at two adjacent serines within the carboxyl terminus. Furthermore, the full length and a carboxyl-terminal fragment of ICP-1 stimulated AIR-2 kinase activity. This increase in AIR-2 activity required that AIR-2 phosphorylate ICP-1 because mutation of both serines in the AIR-2 phosphorylation site of ICP-1 abolished the potentiation of AIR-2 kinase activity by ICP-1. Thus, ICP-1 is directly phosphorylated by AIR-2 and functions in a positive feedback loop that regulates AIR-2 kinase activity. Since the Aurora B phosphorylation site within INCENP and the functions of INCENP and Aurora B have been conserved among eukaryotes, the feedback loop we have identified is also likely to be evolutionarily conserved.

Despite the central importance of the mitotic spindle in cell division, the mechanisms that control spindle dynamics during mitosis remain elusive. One class of proteins that has recently been implicated in coordinating spindle mechanics is the chromosomal passenger proteins (1). This class is composed of the inner centromeric protein INCENP1 (2), the unidentified autoimmune antigen TD-60 (3), the Aurora B kinase (4), and the inhibitor-of-apoptosis repeat-containing protein Survivin/BIR-1 (5, 6). Passenger proteins have been grouped together based upon their shared subcellular localization; they associate with centromeres at metaphase, move to the central spindle microtubules at or just prior to anaphase, and remain at the cytokinesis remnant at the completion of telophase (1). Thus, these proteins are strategically positioned during mitotic progression to play important roles in regulating mitotic spindle dynamics. We are therefore interested in determining the specific function of chromosomal passenger proteins.

INCENP was first identified through a screen of monoclonal antibodies that were raised against chromosome-associated proteins fractionated from chicken cell extracts (7). Immunofluorescence studies with INCENP antibodies revealed the dynamic translocation of INCENP from metaphase chromosomes to the central spindle microtubules at anaphase. Expression of various INCENP truncation constructs in tissue culture cells delineated specific domains of INCENP that are required for its association with microtubules, chromosomes, centromeres, and the central spindle (2).

A function for INCENP was first revealed by studies showing that expression of a mutant INCENP that is unable to bind microtubules prevents proper chromosome alignment and inhibits the completion of cytokinesis in tissue culture cells (2). Similarly, mice homozygous for a null allele of the murine INCENP orthologue die very early in development due to defects in chromosome segregation and cytokinesis (8). Depletion of the Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila INCENP orthologues by RNA interference again led to defects in chromosome segregation and cytokinesis (9, 10). Alignment of INCENP homologues from a variety of species identified a conserved region at the carboxyl terminus, the IN box, which is also found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sli15, an essential protein that is required for proper chromosome segregation in budding yeast (9, 11, 12). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that INCENP is required for chromosome congression at metaphase, for chromosome segregation at anaphase, and late in mitosis for the completion of cytokinesis. These roles are consistent with the evolutionarily conserved dynamic localization pattern of INCENP during mitosis.

Loss of Aurora B kinase expression or activity leads to a phenotype similar to loss of INCENP expression in a variety of organisms. The Aurora/Ipl1 family of protein kinases consists of three subclasses, Aurora A, B, and C, that have been implicated in different aspects of mitotic spindle dynamics (1, 13, 14). The Aurora A kinases localize to centrosomes and are required for centrosome maturation and spindle stability (15-20). The Aurora B kinases display a localization pattern typical of chromosomal passenger proteins and are required for chromosome segregation and the completion of cytokinesis (4, 21). The Aurora C class is found only in mammals and localizes to the centrosomes at anaphase where it performs an unknown function (22). Importantly, both the Aurora A and B kinases are oncogenic when overexpressed and are found at elevated levels in a variety of human cancers (23, 24).

The budding yeast Aurora kinase Ipl1 interacts both physically and genetically with Sli15, a protein that has since been recognized to be an INCENP homologue (9, 11). This interaction appears to be highly conserved as the INCENP and Aurora B proteins from C. elegans and Drosophila have been shown to physically associate in vitro, and both proteins can be co-immunoprecipitated from Xenopus egg and HeLa cell extracts (9, 10, 12). Furthermore, INCENP has been shown to be required for targeting Aurora B to metaphase chromosomes in C. elegans and Drosophila (9, 10), while further studies in Drosophila showed that Aurora B is required for the accumulation of INCENP at centromeres and for the translocation of INCENP to the central spindle at anaphase (10).

The results described above suggest that INCENP may act as a targeting subunit to localize Aurora B to metaphase chromosomes (12). Recently it was found that the Ipl1 kinase binds to and phosphorylates Sli15 at the carboxyl terminus, a region of the protein that contains the highly conserved IN box (25). Furthermore, the binding of Sli15 and Ipl1 produces an increase in Ipl1 kinase activity toward other substrates (25). Thus, the effect of the Aurora B-INCENP interaction, at least in part, may be to potentiate Aurora B kinase activity. We therefore chose to explore whether this mechanism is evolutionary conserved and identify whether phosphorylation of INCENP by Aurora B affects the ability of INCENP to potentiate Aurora B kinase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning

Construction of GST-AIR-2 has been described previously (26). GST-AIR-1 was created by PCR amplification of the AIR-1 coding region from a C. elegans cDNA library. The PCR product was cloned into pCR II-TOPO (Invitrogen) and then subcloned into the BamHI site of pGEX 6P-1 (Amersham Biosciences). GST-ICP-1 was created by PCR amplification of the C. elegans cDNA yk329a11. The PCR product was cloned into pCR II-TOPO and then subcloned into the BamHI/NotI sites of pGEX 6P-1. GST-ICP-1M and -C were similarly created by PCR amplification from the same cDNA, cloned into pCR II-TOPO, and subcloned into BamHI/NotI-digested pGEX 6P-1. GST-ICP-1N was created by double digesting GST-ICP-1 with BamHI/AvaI, gel-purifying the resulting 715-bp fragment containing the first 238 codons of ICP-1, and ligating the fragment into BamHI/XhoI-digested pGEX 6P-1. All site-directed mutants were created by PCR-mediated mutagenesis at the indicated codons by a method described elsewhere (26). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Recombinant Protein Purification and Kinase Assay

Recombinant GST fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) pLys S by overnight induction with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside. 15 ml of bacteria were pelleted, resuspended in 700 μl of lysis buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 40 mM HEPES, 0.2% Triton-X-100, pH 7.6) supplemented with Complete protease inhibitors (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and briefly sonicated on ice. The sonicates were clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatants were added to 10 μl of glutathione beads (Amersham Biosciences) and incubated on ice for 2 h. The beads were thoroughly washed in phosphate-buffered saline, 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.6 and resuspended in 30 μl of elution buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM glutathione). Kinase reactions were performed at room temperature for 10 min in kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 7.5 mM magnesium chloride, 10 nM ATP, 30 μCi (3 Ci/μmol) of [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences)) with ∼100 ng of GST-AIR-2, 100 ng of GST-AIR-2ts, or 100 ng of GST-AIR-1 with 20 ng of GST-ICP-1, and/or 100 ng of myelin basic protein (MBP) (Sigma) in a total volume of 15 μl. Kinase reactions were terminated by the addition of 7 μl of 3× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted to nitrocellulose. Radioactive phosphate incorporation was visualized and quantitated by phosphorimaging. Protein loading was determined by staining membranes with Ponceau S and/or probing with ICP-1- and AIR-2-specific antibodies. The AIR-2 antibody has been previously described (4), and the ICP-1 antibody will be described elsewhere.2

RESULTS

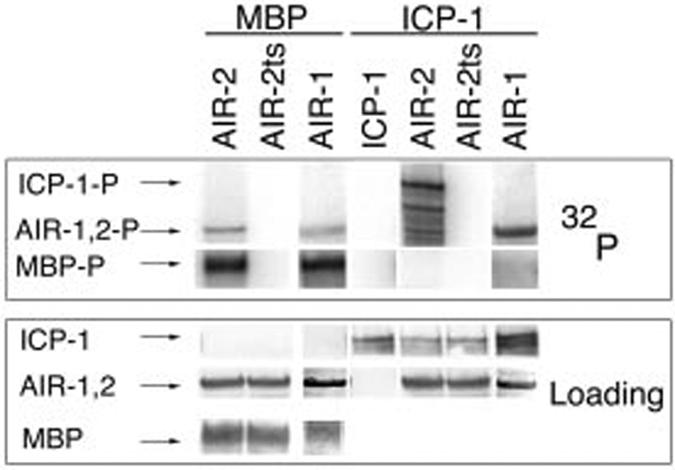

To determine whether the C. elegans INCENP ICP-1 is an in vitro substrate of the C. elegans Aurora B kinase AIR-2, we tested the ability of recombinant GST-AIR-2 to phosphorylate recombinant GST-ICP-1 in vitro. We have previously demonstrated that purified bacterially expressed GST-AIR-2 is active in vitro as it undergoes autophosphorylation and can specifically phosphorylate the meiotic cohesin REC-8 (26). Consistent with previous results, the GST-AIR-2 kinase underwent autophosphorylation and could phosphorylate the generic substrate MBP (Fig. 1, lane 1). The kinase activity was specific to GST-AIR-2 and not caused by a contaminating bacterial activity as preparations of a kinase-inactive GST-AIR-2 mutant corresponding to the in vivo mutation or207ts (27) (GST-AIR-2ts) did not autophosphorylate and had no activity toward MBP (Fig. 1, lane 2). Purified GST-ICP-1 alone, or in the presence of GST-AIR-2ts, similarly exhibited no phosphorylation (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 6). However, in the presence of GST-AIR-2, GST-ICP-1 became strongly phosphorylated (Fig. 1, lane 5). To determine whether ICP-1 is a specific substrate of the AIR-2 kinase, we asked whether GST-ICP-1 could also be phosphorylated by a GST fusion protein corresponding to the C. elegans Aurora A kinase AIR-1 (18). Although GST-AIR-1 was able to undergo autophosphorylation and to phosphorylate MBP (Fig. 1, lane 3), the AIR-1 kinase did not phosphorylate GST-ICP-1 (Fig. 1, lane 7). ICP-1 is therefore a specific in vitro substrate of the AIR-2 kinase.

FIG.1.

GST-AIR-2 specifically phosphorylates GST-INCENP in vitro. In vitro kinase reactions with MBP as a substrate for GST-AIR-2 (lane 1), GST-AIR-2ts (lane 2), and GST-AIR-1 (lane 3) and with GST-ICP-1 alone (lane 4) or as a substrate for GST-AIR-2 (lane 5), GST-AIR-2ts (lane 6), and GST-AIR-1 (lane 7) are shown. Top panel, 32P incorporation. Bottom panel, protein loading as determined by Ponceau S staining (MBP and GST-AIR-1), anti-AIR-2 Western (GST-AIR-2), and anti-ICP-1 Western (GST-ICP-1).

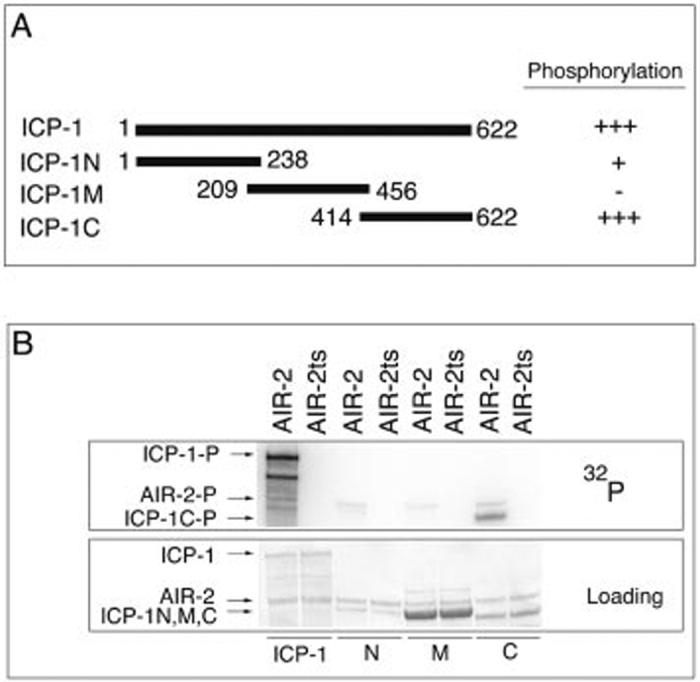

To determine the AIR-2 phosphorylation site in GST-ICP-1, we created three GST fusion proteins consisting of approximately the amino-terminal third (ICP-1N, residues 1-238), middle third (ICP-1M, residues 209-456), and carboxyl-terminal third (ICP-1C, residues 414-622) of ICP-1 (Fig. 2A). GST-ICP-1C was strongly phosphorylated by GST-AIR-2, whereas GST-ICP-1N was weakly phosphorylated, and phosphorylation of GST-ICP-1M was not detectable (Fig. 2B). The observed phosphorylation was specific as none of the proteins were phosphorylated by GST-AIR-2ts. Therefore, GST-ICP-1 is phosphorylated by GST-AIR-2 most strongly at residues within the carboxyl-terminal fragment; however, the amino-terminal fragment also contains at least one site that is weakly phosphorylated by GST-AIR-2.

FIG.2.

The carboxyl terminus of INCENP is strongly phosphorylated by GST-AIR-2. A, schematic of the GST-ICP-1 truncation proteins and relative phosphorylation by GST-AIR-2. B, in vitro kinase reactions with GST-ICP-1 (ICP-1) (lanes 1 and 2), GST-ICP-1N (N) (lanes 3 and 4), GST-ICP-1M (M) (lanes 5 and 6), or GST-ICP-1C (C) (lanes 7 and 8) as substrates for GST-AIR-2 (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) and GST-AIR-2ts (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Top panel, 32P incorporation. Bottom panel, protein loading as determined by Ponceau S staining.

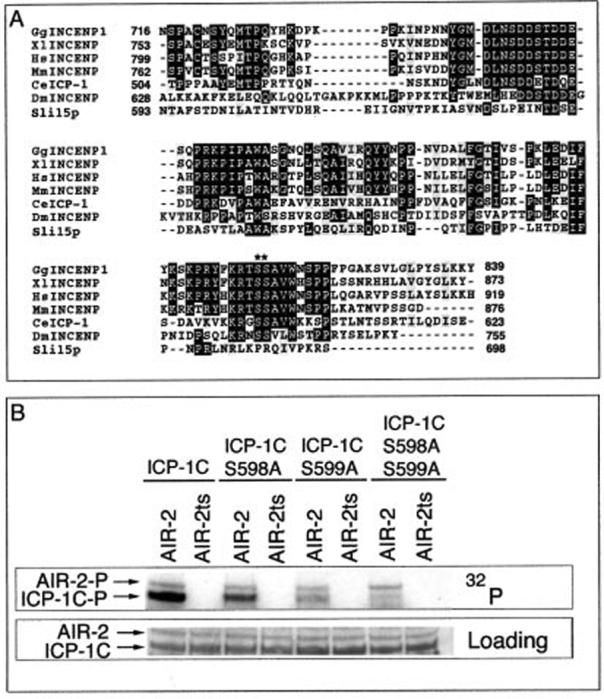

Within ICP-1C there are several serine and threonine residues that are potential AIR-2 phosphorylation sites, including several highly conserved serines in the IN box (Fig. 3A). Site-directed mutagenesis of serines 598 and 599 to alanines significantly diminished the phosphorylation of GST-ICP-1C (Fig. 3B). Ser-598 and Ser-599 appear to be additively phosphorylated as each single mutant was phosphorylated less strongly than GST-ICP-1C but more strongly than the double mutant ICP-1C (S598A/S599A). Mutation of these same residues in the full-length GST-ICP-1 protein revealed that these sites are also responsible for the majority of phosphate incorporation as GST ICP-1 (S598A/S599A) was significantly less phosphorylated by GST-AIR-2 (Fig. 4A, lane 4). The remaining signal is likely to be a result of phosphorylation at residues in the amino terminus as seen with GST-ICP-1N. Thus, serines 598 and 599 appear to be the primary sites through which the AIR-2 kinase specifically phosphorylates ICP-1.

FIG.3.

Serines 598 and 599 are additively phosphorylated by GST-AIR-2. A, the carboxyl-terminal IN box is highly conserved across species (with accession numbers from GenBank™ (AF) and NCBI (gi) in parentheses): chicken (GgINCENP1, gi 2134313), Xenopus (XlINCENP, gi 2072290), human (HsINCENP, gi 9438179), mouse (MmINCENP, gi 4886899), C. elegans (CeICP-1, AF300704), Drosophila melanogaster (DmINCENP, gi 17647535) and S. cerevisiae (Sli15p, gi 6319632). As-terisks denote the conserved serines that are phosphorylated by AIR-2. B, in vitro kinase reactions with GST-ICP-1C (lanes 1 and 2), GST-ICP-1C (S598A) (lanes 3 and 4), GST-ICP-1C (S599A) (lanes 5 and 6), or GST-ICP-1C (S598A/S599A) (lanes 7 and 8) as substrates for GST-AIR-2 (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) and GST-AIR-2ts (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Top panel, 32P incorporation. Bottom panel, protein loading as determined by Ponceau S staining.

FIG.4.

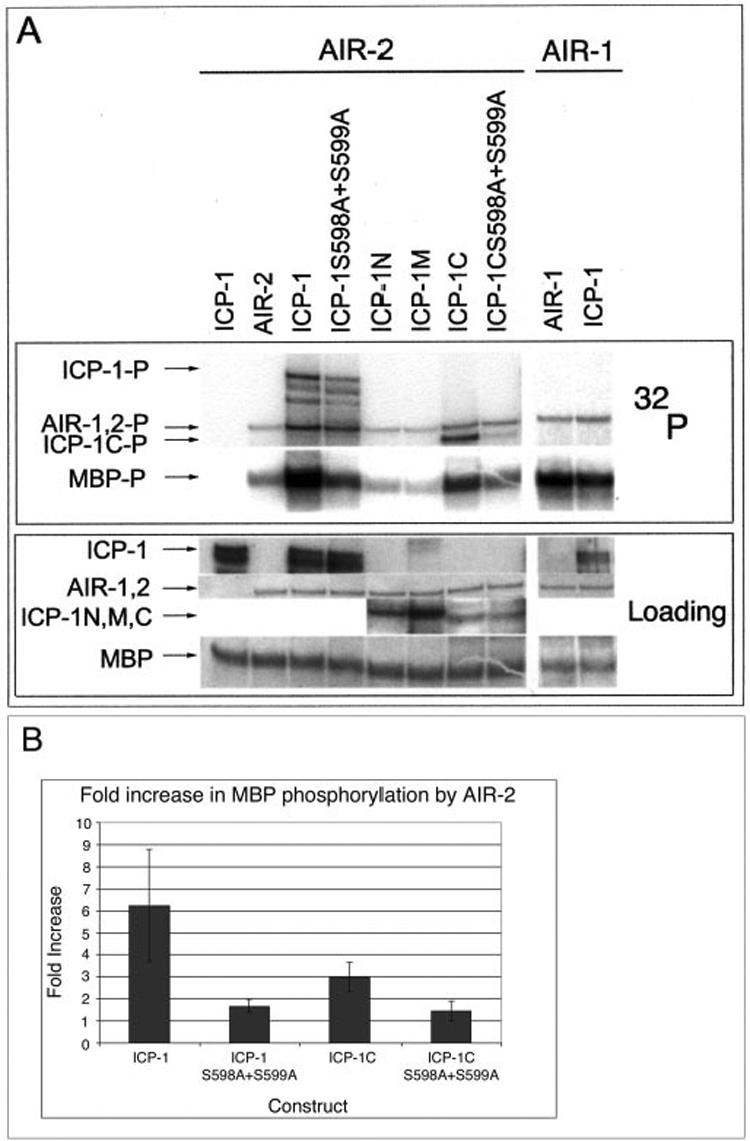

Wild-type GST-ICP-1 and GST-ICP-1C, but not the S598A/S599A mutants, stimulate GST-AIR-2 kinase activity. A, lanes 1-8, in vitro phosphorylation of MBP by either GST-ICP-1 alone (lane 1), GST-AIR-2 alone (lane 2), or GST-AIR-2 supplemented with GST-ICP-1 (lane 3), GST-ICP-1 (S598A/S599A) (lane 4), GST-ICP-1N (lane 5), GST-ICP-1M, (lane 6), GST-ICP-1C (lane 7), or GST-ICP-1C (S598A/S599A) (lane 8). Lanes 9 and 10, in vitro phosphorylation of MBP by either GST-AIR-1 alone (lane 9) or GST-AIR-1 supplemented with GST-ICP-1 (lane 10). Top panel, 32P incorporation. Bottom panel, protein loading as determined by Ponceau S staining (MBP, GST-AIR-2, and GST-AIR-1) or anti-ICP-1 Western. B, 32P incorporation into MBP by GST-AIR-2 in the presence of GST-ICP-1 (n = 7), GST-ICP-1 (S598A/S599A) (n = 3), GST-ICP-1C (n = 4), and GST-ICP-1C (S598A/S599A) (n = 3) was quantified by phosphorimaging. Error bars indicate one standard deviation.

The S. cerevisiae INCENP orthologue Sli15 can enhance the in vitro kinase activity of the yeast Aurora kinase Ipl1 (25). We therefore tested whether the ability to augment Aurora B kinase activity is evolutionarily conserved between yeast and nematode INCENPs. The effect of GST-ICP-1 on GST-AIR-2 activity was measured by assessing the level of GST-AIR-2-mediated MBP phosphorylation in the presence and absence of GST-ICP-1. GST-ICP-1 significantly increased MBP phosphorylation by GST-AIR-2 (Fig. 4, A, lanes 2 and 3, and B); however, it did not increase MBP phosphorylation by GST-AIR-1 (Fig. 4A, lanes 9 and 10).

To determine the specific domain of ICP-1 that is required for the enhancement of AIR-2 kinase activity, we tested the ability of the GST-ICP-1N, -M, and -C fragments to stimulate GST-AIR-2 phosphorylation of MBP. Addition of GST-ICP-1C resulted in a significant increase in GST-AIR-2 activity, whereas GST-ICP-1N and GST-ICP-1M did not (Fig. 4, A, lanes 2 and 5-7, and B). Since the ICP-1C domain contains the primary AIR-2 phosphorylation site (Ser-598 and Ser-599), we asked whether these residues were necessary for ICP-1-mediated enhancement of AIR-2 kinase activity. Neither GST-ICP-1 (S598A/S599A) nor GST-ICP-1C (S598A/S599A) was able to stimulate GST-AIR-2 phosphorylation of MBP above base-line levels (Fig. 4, A, lanes 4 and 8, and B). These results suggest that ICP-1 must be phosphorylated by AIR-2 for ICP-1 to enhance AIR-2 kinase activity.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrate for the first time that metazoan INCENPs are specific substrates of Aurora B kinases. Furthermore, we have identified residues within C. elegans INCENP that are phosphorylated by C. elegans Aurora B. Although the majority of the INCENP primary amino acid sequence is divergent, the Aurora B phosphorylation site is highly conserved across a range of species. This suggests that this site is critically important for INCENP function.

The data presented here confirm and extend previous results from budding yeast (25) by demonstrating that C. elegans INCENP has the ability to up-regulate the kinase activity of Aurora B and that the conserved IN box domain in the carboxyl terminus of INCENP is necessary for this effect. This stimulation is specific for Aurora B as the C. elegans Aurora A kinase was not stimulated by ICP-1. Furthermore, we show that the ability of INCENP to augment Aurora B activity is dependent on the presence of phosphorylated serine residues within the IN box. The simplest conclusion from these data is that phosphorylation of these residues by the Aurora B kinase is required for INCENP to stimulate Aurora B kinase activity. However, it is formally possible that the serine to alanine mutations perturb the folding or function of GST-ICP-1 in a manner unrelated to phosphorylation at these sites. However, when these critical serines were mutated individually, the resulting proteins retained an ability to stimulate AIR-2 kinase activity at a level that is intermediate between GST-ICP-1 and the serine double mutant (data not shown). These results correlate the level of ICP-1 phosphorylation with the level of AIR-2 stimulation, supporting the conclusion that loss of phosphorylation, rather than an overall folding problem, is responsible for the inability of GST-ICP-1 (S598A/S599A) to stimulate AIR-2 kinase activity.

The mechanism by which phosphorylated INCENP up-regulates the Aurora B kinase remains to be determined. It will be interesting to address whether Aurora B activity is increased toward a large number of substrates or only a small subset. As INCENP appears to act as a targeting subunit for Aurora B it will be important to determine whether serines 598 and 599 are also required for the localization of the Aurora B kinase in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Heallen for expert technical assistance, Y. Kohara for providing the cDNA yk329a11, and K. Roeder for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM62181-01 and a V-Foundation scholar award (to J. M. S.). All sequencing was performed at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson DNA Sequencing Core funded by NCI, National Institutes of Health Grant CA-16672. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

- INCENP

- inner centromere protein

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- MBP

- myelin basic protein

J. D. Bishop and J. M. Schumacher, unpublished data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams RR, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01880-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackay AM, Ainsztein AM, Eckley DM, Earnshaw WC. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:991–1002. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreassen PR, Palmer DK, Wener MH, Margolis RL. J. Cell Sci. 1991;99:523–534. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumacher JM, Golden A, Donovan PJ. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1635–1646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uren AG, Wong L, Pakusch M, Fowler KJ, Burrows FJ, Vaux DL, Choo KHA. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1319–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00769-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speliotes EK, Uren A, Vaux D, Horvitz HR. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke CA, Heck MM, Earnshaw WC. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:2053–2067. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutts SM, Fowler KJ, Kile BT, Hii LL, O’Dowd RA, Hudson DF, Saffery R, Kalitsis P, Earle E, Choo KH. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:1145–1155. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaitna S, Mendoza M, Jantsch-Plunger V, Glotzer M. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams RR, Maiato H, Earnshaw WC, Carmena M. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:865–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JH, Kang JS, Chan CS. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:1381–1394. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.7.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams RR, Wheatleya SP, Gouldsworthy AM, Kandels-Lewis SE, Carmena M, Smythe C, Gerloff DL, Earnshaw WC. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1075–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bischoff JR, Plowman GD. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:454–459. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giet R, Prigent C. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:3591–3601. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glover DM, Leibowitz MH, McLean DA, Parry H. Cell. 1995;81:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura M, Kotani S, Hattori T, Sumi N, Yoshioka T, Todokoro K, Okano Y. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13766–13771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopalan G, Chan CS, Donovan PJ. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:643–656. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schumacher JM, Ashcroft N, Donovan PJ, Golden A. Development. 1998;125:4391–4402. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roghi C, Giet R, Uzbekov R, Morin N, Chartrain I, Le Guellec R, Couturier A, Doree M, Philippe M, Prigent C. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:557–572. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannak E, Kirkham M, Hyman AA, Oegema K. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:1109–1116. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terada Y, Tatsuka M, Suzuki F, Yasuda Y, Fujita S, Otsu M. EMBO J. 1998;17:667–676. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura M, Matsuda Y, Yoshioka T, Okano Y. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7334–7340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou H, Kuang J, Zhong L, Kuo WL, Gray JW, Sahin A, Brinkley BR, Sen S. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:189–193. doi: 10.1038/2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bischoff JR, Anderson L, Zhu Y, Mossie K, Ng L, Souza B, Schryver B, Flanagan P, Clairvoyant F, Ginther C, Chan CS, Novotny M, Slamon DJ, Plowman GD. EMBO J. 1998;17:3052–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang J, Cheeseman IM, Kallstrom G, Velmurugan S, Barnes G, Chan CS. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:763–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers E, Bishop JD, Waddle JA, Schumacher JM, Lin R. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:219–229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Severson AF, Hamill DJ, Carter JC, Schumacher JM, Bowerman B. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1162–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]