Abstract

BACKGROUND

Uncertainty shapes many decisions made by physicians everyday. Uncertainty and physicians’ inability to handle it may result in substandard care and unexplained variations in patterns of care.

OBJECTIVE

To describe socio-demographic and professional characteristics of reactions to uncertainty among physicians from all specialties, including physicians in training.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional postal survey.

PARTICIPANT

All physicians practicing in Geneva, Switzerland (n = 1,994).

MEASUREMENT

Reaction to medical care uncertainty was measured with the Anxiety Due to Uncertainty and Concern About Bad Outcomes scales. The questionnaire also included items about professional characteristics and work-related satisfaction scales.

RESULTS

After the first mailing and two reminders, 1,184 physicians responded to the survey. In univariate analysis, women, junior physicians, surgical specialists, generalist physicians, and physicians with lower workloads had higher scores in both scales. In multivariate models, sex, medical specialty, and workload remained significantly associated with both scales, whereas clinical experience remained associated only with concern about bad outcomes. Higher levels of anxiety due to uncertainty were associated with lower scores of work-related satisfaction, while higher levels of concern about bad outcomes were associated with lower satisfaction scores for patient care, personal rewards, professional relations, and general satisfaction, but not for work-related burden or satisfaction with income-prestige. The negative effect of anxiety due to uncertainty on work-related satisfaction was more important for physicians in training.

CONCLUSION

Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in medical care were associated with several dimensions of work-related satisfaction. Physicians in training experienced the greatest impact of anxiety due to uncertainty on their work-related satisfaction. Incorporating strategies to deal with uncertainty into residency training may be useful.

KEY WORDS: uncertainty, quality of care, medical training, work-related satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

Uncertainty shapes many decisions made by clinicians everyday and is so ubiquitous that physicians must learn to tolerate ambiguity if they are to provide quality care to patients who suffer from complex conditions.1–4 Medical uncertainty can have several sources: limited medical knowledge, unpredictability of the natural course of disease and of the patients’ response to treatment, and variability in the physicians’ and patients’ values and attitudes toward risk.1,5–11 The discovery that medicine is an uncertain science typically starts in medical school.12 Young physicians in training may be unsure about their knowledge and skills or whether the relevant knowledge exists to begin with, and they may be unable to distinguish between the two.13,14 For practicing physicians, technical uncertainty caused by inadequate scientific data, personal uncertainty that arises from not knowing patients’ wishes, and conceptual uncertainty due to the difficulty of applying abstract criteria to concrete situations have been described.3,15 Thus, both uncertainty and the doctors’ inability to handle it may result in substandard care3,16 and cause unexplained variations in patterns of care.1,3,9,17 Medical care uncertainty can also affect physicians’ work-related satisfaction. In a survey of 1,755 Swiss primary care physicians, an increased level of self-reported stress due to medical care uncertainty was associated with a higher risk of burnout18 that can result in decreased job performance, lower career satisfaction,19–21 and lower quality care.22

Despite the importance of uncertainty in medical care, studies including physicians from all medical specialties from graduation to retirement have not been reported. Furthermore, the importance of uncertainty as a correlate of physicians’ work-related satisfaction, an important indicator of quality care, has never been studied. In this paper, we used the data from a population-based survey of physicians practicing in Geneva, Switzerland, including physicians in training, to explore the relationship between physicians’ reactions to medical care uncertainty and socio-demographic and professional characteristics including work-related satisfaction.

METHODS

Context

In Switzerland, medical students can enroll in 1 of 5 medical schools, for a 6-year graduate program. Having obtained their medical degree, most physicians initiate postgraduate training, which lasts 5–8 years. Residency programs in General Medicine, General Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Psychiatry last 5 years, in general. Internal Medicine Specialists and Surgical Specialists have longer training. Most doctors then go into private practice in the community.

Sample and Study Design

We conducted a mail survey of all physicians practicing in canton Geneva, Switzerland, during the autumn of 1998. Physicians were identified from membership files of the Geneva Medical Association (1,370 members) and the Swiss Association of Interns/Registrars, Geneva Section (906 members). After exclusion of 54 duplicate records, 10 pretest participants, 97 doctors who had incorrect addresses, and 121 who did not practice clinical medicine, 1,994 physicians remained eligible.

Most members of the Geneva Medical Association work in the private sector, either in solo or group practice, and are paid on a fee-for-service basis. A minority of the physicians work in private clinics or are salaried in a medical center. Members of the Swiss Association of Interns/Registrars are mainly salaried junior physicians working at the single public hospital of Geneva. Senior staff at the public hospital can belong to either association.

Measurement of Reaction to Medical Care Uncertainty

Reaction to medical care uncertainty was measured with two scales derived from the Physicians’ Reactions to Uncertainty instrument,7,23,24 the Anxiety Due to Uncertainty and Concern About Bad Outcomes scales (Appendix 1). These scales had a high internal reliability (Cronbach α 0.86 and 0.73, respectively) and were designed to measure mutable physician attitudes about uncertainty. We chose it over other scales designed to measure uncertainty, such as the Tolerance for Ambiguity scale,6 which measures personality traits rather than attitudes. Attitudes may change with experience, education, or environment,16 while personality trait are believed to be immutable.

Table 4.

Original English and French Translation of the Items Measuring the Two Dimensions of the Stress from Uncertainty Scale

| Anxiety due to uncertainty | |

|---|---|

| The uncertainty of patient care often troubles me | Je trouve que l’incertitude liée à la prise en charge des patients est déconcertante |

| I find the uncertainty involved in patient care disconcerting | L’incertitude lors de la prise en charge des patients me dérange souvent |

| I usally feel anxious when I am not sure of a diagnosis | Je suis généralement anxieux quand je ne suis pas sûr d’un diagnostic |

| Uncertainty in patient care makes me uneasy | L’incertitude liée à la prise en charge des patients me met mal à l’aise |

| I am quite comfortable with the uncertainty in patient care* | Je suis à l’aise face à l’incertitude liée à la prise en charge des patients* |

| Concern about bad outcomes | |

| When I am uncertain of a diagnosis, I imagine all sorts of bad scenarios (patient dies, patient sues, etc...) | Quand je ne suis pas sûr d’un diagnostic, j’imagine toutes sortes de scénarios catastrophes (le patient meurt, me poursuit en justice, etc.) |

| I fear being held accountable for the limits of my knowledge | J’ai peur qu’on puisse me reprocher les limites de mes connaissances médicales |

| I worry about malpractice when I do not know a patient’s diagnosis | J’ai peur de commettre une faute professionnelle quand je ne connais pas le diagnostic d’un patient. |

Response options ranged from 1: totally disagree/Pas du tout d’accord to 5: totally agree/Tout à fait d’accord

*Item reversed scored for the summary scale

We translated these scales into French using a standardized procedure including three independent translations, selection of a consensus translation by an expert panel, and pretests among 10 physicians (Appendix 1). The items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by 1: totally disagree and 5: totally agree. Scores of negatively worded items were reversed so that a higher score would mean greater anxiety due to uncertainty or concern about bad outcomes. The internal consistency of the translated scales were similar to that of the original scales (Cronbach α 0.81 and 0.67, respectively).

Table 5.

Original French and English Translation of Items Measuring Physician Job Satisfaction

| Veuillez indiquer dans quelle mesure vous êtes satisfait avec les aspects suivants de votre vie professionnelle : | Please indicate how satisfied you are with the following aspects of your professional life |

|---|---|

| Soins aux patients | Patient Care |

| Vos relations avec vos patients | Your relations with your patients |

| La possibilité que vous avez de traiter vos patients comme vous l’entendez | The possibility to treat your patients as you see it |

| La possibilité que vous avez d’adresser vos patients à un spécialiste chaque fois que vous l’estimez nécessaire | The possibility to refer your patients to a specialist whenever you think it is necessary |

| La qualité des soins que vous êtes à même de dispenser | The quality of care you are able to provide |

| Inconvénients | Burden |

| Votre charge de travail | Your workload |

| Le temps que vous pouvez consacrer à votre famille, vos amis, ou vos loisirs | The time you have for family, friends or leisure activities |

| Le niveau de stress auquel vous êtres soumis dans l’exercice de votre profession | The level of stress you experience at work |

| Le temps et l’énergie consacrés aux tâches administratives | The time and energy you spend on administrative tasks |

| Revenu-prestige | Income prestige |

| Votre revenu actuel | Your current income |

| La manière dont vous êtes actuellement rétribué (honoraires à l’acte, salaire, forfait, etc.) | The way you are currently paid (fee-for-service, salary, capitation, etc.) |

| Votre position sociale et le respect dont on vous témoigne | Your social status and the respect people show you |

| Récompenses personnelles | Personal rewards |

| Votre stimulation intellectuelle au travail | Your intellectual stimulation at work |

| Vos possibilités de formation continue | Your opportunities for continuing medical education |

| Votre plaisir à travailler | Your enjoyment at work |

| Relations professionnelles | Professional relations |

| Vos relations et échanges professionnels avec d’autres médecins | Your professional relations and interactions with other medical doctors |

| Vos relations avec vos collaborateurs non-médecins (infirmier(ère), assistant(e), etc.) | Your relations with non medical staff (nurse, assistant) |

| Question générale | General item |

| Tout compte fait, votre situation professionnelle en ce moment | All things considered, your professional situation at this time |

The original items were developed in French; the translation in English was done by the authors and checked by a native English speaker. Response options ranged from 1: extrêmement insatisfait—extremely dissatisfied to 7: extrêmement satisfait—extremely satisfied.

Determinants of Medical Care Uncertainty

Physicians’ characteristics included socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex), professional experience (time since graduation from medical school), type of training (board-certification, medical specialty), type of practice (community vs hospital-based), and workload (number of patients per week).

Work-related satisfaction was measured by a locally developed and validated 17-item instrument25 based on the main component of work satisfaction identified by qualitative research of the Society of General Internal Medicine Career Satisfaction Study Group.26 These items addressed five dimensions of work-related satisfaction: “patient care”, “work-related burden”, “income-prestige”, “personal rewards”, and “professional relations” (Appendix 2). These five dimensions were identified based on an exploratory factor analysis, using principal component analysis with varimax rotation, and they captured 67% of the total variance in physician responses. These subscales had satisfactory internal consistency (0.76, 0.79, 0.83, 0.71, and 0.66, respectively). A single item was also used to reflect general work satisfaction. Respondents rated the items using a 7-point Likert scale anchored by 1: extremely dissatisfied and 7: extremely satisfied.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Physicians’ Scores on the Stress from Uncertainty and Work-related Satisfaction Scales (n = 1,189)

| Scales and items | N missing | Mean score (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Stress from uncertainty scales | ||

| Anxiety due to uncertainty (5 items, alpha 0.81)* | 26 | 44.9 (22.1) |

| Concern about bad outcomes (3 items, alpha 0.67)† | 24 | 37.9 (22.8) |

| Work-related Satisfaction scales‡ | ||

| Patient care (4 items, alpha 0.76) | 12 | 5.8 (0.8) |

| Work-related burden (4 items, alpha 0.79) | 9 | 3.6 (1.2) |

| Income-prestige (3 items, alpha 0.83) | 9 | 4.6 (1.3) |

| Personal rewards (3 items, alpha 0.71) | 10 | 5.4 (1.0) |

| Professional relations (2 items, alpha 0.66) | 10 | 5.8 (0.9) |

| General satisfaction (1 item) | 16 | 5.1 (1.2) |

*Summary scores were calculated whenever responses for 3 or more items were present and then rescaled to range from 0 and 100, where 0 corresponded to the lowest anxiety due to uncertainty level.

†Scale scores were calculated whenever responses for 2 or more items were present and then rescaled to range from 0 and 100, where 0 corresponded to the lowest concern about bad outcomes level.

‡Scales scores were calculated whenever responses for half or more items were present. Scores were averaged across the number of items in each scale so all scale scores range from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each item of the Anxiety Due to Uncertainty and Concern About Bad Outcomes scales (mean, standard deviation, quartiles, number missing). For each scale, a summary score was calculated by averaging the responses whenever at least half or more of the items were present. Both uncertainty scores were rescaled between 0 and 100 using a linear transformation, where 0 corresponded to the lowest level and 100 to the highest. For the five satisfaction scales, scores were constructed by averaging items in each scale whenever at least half or more of the items were present. Thus, scale scores ranged from 1 to 7 with greater scores corresponding to greater satisfaction.

First, we studied the relationships of anxiety due to uncertainty and concern about bad outcomes across socio-demographic and job characteristics of the respondents using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for categorical variable. In ANOVA, the between-group variance can be partitioned into 2 components: the linear trend (1 df) across the categories and the deviation from linearity (for k groups, k-2 df). The linear trend test is equivalent to doing a linear regression model with the group number entered as a continuous covariate. Because clinical experience has been reported as an important determinant,24 we defined 6 categories based on time since graduation from medical school, board-certification, and type of practice: hospital-based physicians in training for less than 4 years, in training for over 4 years, or completed training (board-certified), and community-based physicians in practice 4 years or less, 5–10 years, or 11 years or more. We also studied the relationship with workload, using self-reported number of patients per week categorized into 4 groups (<26, 26–50, 51–75, >75). To adjust for confounding, significant factors in the univariate analysis were used to compute adjusted means using general linear models. In multivariate analysis, we first ran a multi-way ANOVA to obtain adjusted means. Then, to obtain linear trend tests, we treated ordinal factors as continuous covariates, one at a time. We also tested whether hospital-based physicians would differ from community based-physicians using an interaction term between medical specialty and hospital-based practice. Age was not included in the regression models due to colinearity with clinical experience.

Second, we explored the relationship between uncertainty and work-related satisfaction and computed mean scores of Anxiety Due to Uncertainty and Concern About Bad Outcomes scales across tertiles of all dimensions of work-related satisfaction, adjusting for other factors significantly associated with reactions to uncertainty based on the preceding analysis. ANOVA and test for linear trends were used to evaluate these associations.

Finally, we explored graphically whether the relationship between work-related satisfaction (using a T-score based on all 17 items) and uncertainty scores would vary across levels of socio-demographic and professional characteristics using scatter-plots. To avoid the assumption of linearity, we applied nonparametric regression lines (LOWESS).27 All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 11.0). All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of .05. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons because we thought it would not improve statistical inference in this work.28 Instead, we preferred to provide adjusted 95% confidence intervals around our estimates.

RESULTS

After the first mailing and two reminders, 1,184 physicians (59%) responded to the survey. Seven hundred eighty-four (66%) were men, and their mean age was 44.9 years (SD: 10.9; quartiles: 36, 44, 52). Most respondents were board-certified and in community-based practice (n = 717, 61%), 254 (21%) were hospital interns or registrars in training, and 213 (18%) were board-certified hospital-based physicians. A third (n = 402, 34%) were Generalist Physicians, 196 (17%) Internal Medicine Subspecialists, 178 (15%) Psychiatrists, 83 (7%) Pediatricians, and 325 (27%) other Specialists. On average, respondents had graduated from medical school 17.8 years earlier (SD 10.3; quartiles: 10, 17, 24). As a measure of workload, the mean self-reported number of patients seen per week was 50.6 (SD 30.5; quartiles: 28, 45, 70).

Reaction to Medical Care Uncertainty

Over ninety percent of the respondents rated all items of the Anxiety Due to Uncertainty (n = 1,100, 93%) and Concern About Bad Outcomes (n = 1,140, 96%) scales. Distributions of the ratings were close to normal, except for the first item of the Concern About Bad Outcomes scale, whose distribution was skewed toward the lowest end of the scale. Scores for the Anxiety Due to Uncertainty and Concern About Bad Outcomes scales were computed for 1,158 (98%) and 1,160 (98%) respondents, respectively (Table 1). Scores covered the entire range measured by the scales, and their distribution appeared to be approximately normal. After rescaling, the mean values were 44.9 (SD, 22.1; quartile: 30, 45, 60) for the Anxiety Due to Uncertainty scale and 37.9 (SD 22.8; quartile: 25, 33.3, 58.3) for the Concern About Bad Outcomes scale.

Characteristics Associated with Reactions to Uncertainty

In univariate analysis, women physicians had greater anxiety due to uncertainty and concern about bad outcomes (Table 2). Clinical experience was also strongly associated with scores on both scales: physicians in early stages of their careers had substantially higher scores than physicians in later stages of their careers. With regard to Medical Specialties, Psychiatrists and Internal Medicine Subspecialists (e.g., Cardiologists, Gastroenterologists) had the least anxiety and concern about bad outcomes, and technical specialists (e.g., Surgeons, Anesthesiologists) and Generalist Physicians (especially noncertified practitioners) had the greatest anxiety and concern about bad outcomes. Of interest, workload was also associated with greater anxiety and concern about bad outcomes.

Table 2.

Anxiety Due to Uncertainty and Concern about Bad Outcomes by Demographic Characteristics of 1,184 Physicians in Geneva, Switzerland

| Anxiety due to uncertainty | Concern about bad outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Unadjusted score | P value | Adjusted score* (95% CI) | P value | Unadjusted score | P value | Adjusted scorea (95% CI) | P value | |

| Clinical experience | <.001 | .07† | <.001† | <.001† | |||||

| Hospital-based | |||||||||

| In training for less than 4 years | 42 (3.5) | 54.5 | 50.1 (42.9 to 57.3) | 45.8 | 42.8 (35.3 to 50.3) | ||||

| In training for over 4 years | 212 (17.9) | 50.0 | 47.9 (44.5 to 51.3) | 43.5 | 40.6 (37.0 to 44.2) | ||||

| Board-certified | 213 (18.0) | 44.4 | 42.1 (38.7 to 45.6) | 41.3 | 40.3 (36.7 to 43.9) | ||||

| Community-based | |||||||||

| 0–4 year | 183 (15.5) | 46.4 | 45.7 (42.4 to 49.1) | 39.0 | 37.8 (34.3 to 41.3) | ||||

| 5–10 years | 176 (14.9) | 40.7 | 41.7 (38.4 to 45.0) | 33.2 | 34.3 (30.8 to 37.8) | ||||

| 11 years or more | 358 (30.2) | 42.0 | 44.2 (41.6 to 46.7) | 33.3 | 34.4 (31.7 to 37.1) | ||||

| Sex | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .009 | |||||

| Men | 784 (66.2) | 41.8 | 41.7 (39.5 to 43.9) | 35.7 | 36.4 (34.1 to 38.7) | ||||

| Women | 400 (33.8) | 50.8 | 48.8 (46.3 to 51.4) | 42.3 | 40.3 (37.7 to 43.0) | ||||

| Medical specialty | <.001 | <.001 | .003 | .001 | |||||

| Generalist physicians‡ | 402 (34.0) | 46.6 | 48.0 (45.6 to 50.4) | 40.9 | 42.2 (39.7 to 44.1) | ||||

| Pediatricians | 83 (7.0) | 43.2 | 46.8 (41.7 to 51.9) | 38.0 | 41.5 (36.2 to 46.8) | ||||

| Internal medicine subspecialists | 196 (16.6) | 41.0 | 43.4 (40.0 to 46.8) | 33.7 | 34.6 (31.0 to 38.2) | ||||

| Psychiatrists | 178 (15.0) | 39.4 | 37.6 (33.7 to 41.5) | 35.5 | 34.4 (30.3 to 38.5) | ||||

| “Technical” specialties§ | 325 (27.4) | 48.5 | 50.6 (47.9 to 53.3) | 38.0 | 39.2 (36.4 to 42.1) | ||||

| Self-reported number of patients per week (83 missing) | .004† | .003† | <.001† | .02† | |||||

| <26 | 269 (24.4) | 45.6 | 46.9 (44.0 to 49.9) | 39.8 | 39.7 (36.6 to 42.8) | ||||

| 26–50 | 409 (37.1) | 46.3 | 48.0 (45.5 to 50.4) | 39.9 | 41.4 (38.8 to 44.0) | ||||

| 51–75 | 195 (17.7) | 46.1 | 45.8 (42.4 to 49.3) | 36.3 | 37.9 (34.3 to 41.5) | ||||

| >75 | 228 (20.7) | 39.8 | 40.4 (36.9 to 43.9) | 32.4 | 34.5 (30.8 to 38.2) | ||||

*Observations, 1,059, were included in the regression models, and all scores were adjusted for all factors listed in the table.

†P values are based on the ANOVA test for linearity.

‡Includes 238 General Internists, 92 General Practitioners, and 72 noncertified practitioners

§Including 45 Anesthesiologists, 117 Surgeons (including Subspecialties and Orthopedics), 17 Ear Nose Throat Specialists, 64 Gynecologist-Obstetricians, 26 Dermatologists, 37 Ophthalmologists, and 16 Radiologists

In multivariate analyses, sex, medical specialty, and workload remained significantly associated with both scores. The association with clinical experience remained significant only for concern about bad outcomes (Table 2). In addition, hospital-based physicians tended to have lower scores than community based doctors, but these differences were only significant for General Internists and General Practitioners and were no longer significant after adjusting for socio-demographic and professional characteristics.

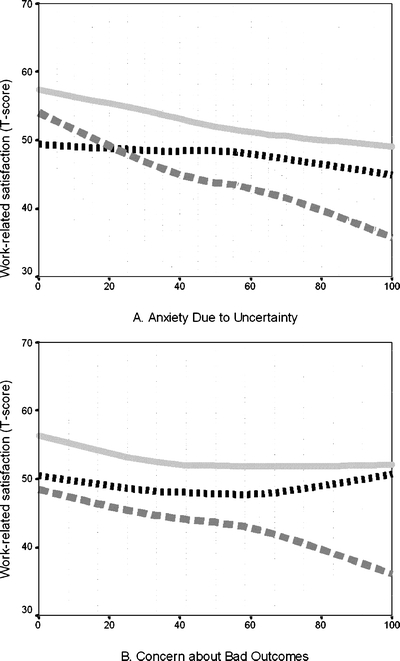

Relationship between Reaction to Uncertainty and Work-Related Satisfaction

Scores on the Anxiety Due to Uncertainty scale were statistically associated with all dimensions of work-related satisfaction (Table 3). For Concern About Bad Outcomes, only the dimensions of patient care and personal rewards displayed a strong association; a weak association was found for professional relations and general satisfaction. We further examined the association between reaction to uncertainty and work-related satisfaction graphically across levels of socio-demographic and professional characteristics. For levels of clinical experience, we found that the negative linear association was much steeper for hospital-based doctors in training (Fig. 1). We tested this impression in a linear regression model including reaction to uncertainty scores and clinical experience dichotomised into 2 categories (in training vs others), as predictors of work-related satisfaction. The interaction term between uncertainty scores and clinical experience was statistically significant for anxiety due to uncertainty (P = .04), but not for concern about bad outcomes (P = .14), indicating that the effect of anxiety due to uncertainty on work-related satisfaction was more important for doctors in training.

Table 3.

Relationship Between Reactions to Medical Care Uncertainty and Work-related Satisfaction for 1,184 Physicians in Geneva, Switzerland

| Anxiety due to uncertainty (mean score) | P Value | Concern about bad outcomes (mean score) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Care | <.001* | .004* | ||

| Lowest tertile | 50.5 | 41.9 | ||

| Intermediatetertile | 43.9 | 36.5 | ||

| Highest tertile | 41.4 | 36.7 | ||

| Work-related Burden | .001* | .09* | ||

| Lowest tertile | 48.3 | 40.2 | ||

| Intermediate tertile | 45.3 | 38.2 | ||

| Highest tertile | 42.6 | 37.1 | ||

| Income-prestige | .004* | .62* | ||

| Lowest tertile | 47.7 | 38.4 | ||

| Intermediate tertile | 46.2 | 40.5 | ||

| Highest tertile | 43.2 | 37.6 | ||

| Personal Rewards | <.001* | .001* | ||

| Lowest tertile | 49.2 | 41.3 | ||

| Intermediate tertile | 47.3 | 39.2 | ||

| Highest tertile | 40.9 | 35.7 | ||

| Professional Relations | .02* | .04* | ||

| Lowest tertile | 47.4 | 40.6 | ||

| Intermediate tertile | 45.2 | 37.7 | ||

| Highest tertile | 43.6 | 37.1 | ||

| General Satisfaction | <.001* | .05* | ||

| Lowest tertile | 50.1 | 40.8 | ||

| Intermediate tertile | 46.2 | 38.7 | ||

| Highest tertile | 42.3 | 37.3 |

All scores are adjusted for sex, age, clinical experience, medical specialty, and workload (self-reported number of patients per week).

*P values are based on ANOVA test for linearity.

Figure 1.

Relationship between work-related satisfaction and reactions to uncertainty scores for three different levels of clinical experience among 1,184 doctors in Geneva, Switzerland (light gray solid line: community-based doctors, black dotted line: hospital-based senior doctors, gray broken line: hospital-based doctors in training). Lines represent nonparametric regression estimates (LOWESS).

DISCUSSION

Our findings bring new insights on the importance of measuring reactions to uncertainty in medical care. Despite an abundant qualitative literature about the importance of uncertainty in medical care,1–3,11,12,14,15,17,29 we are one of a few authors who have addressed this problem quantitatively.8,9,16,30 First, we found several socio-demographic and professional characteristics associated with medical care uncertainty. Similar to findings reported years ago by Gerrity et al.7 in a study of U.S. physicians, we found that reactions to uncertainty were higher in women and among physicians in technical specialties, and lower for physicians with a greater number of years in practice. It was highest for recently graduated physicians and lowest for physicians who had an established private practice for 5 years or more. Beyond that point, the levels of stress from uncertainty remained stable. Across Medical Specialities, Psychiatrist and Internal Medicine Subspecialists displayed the lowest scores.

In addition, we found that physicians who saw many patients per week reported lower stress from uncertainty—an association that has not been previously reported. Possibly, physicians who cope with uncertainty better spend less time considering alternative diagnoses and courses of action, and are thus able to see more patients. Conversely, it may be the greater clinical experience accumulated by seeing many patients that reduces the physicians’ stress from uncertainty. Because of the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot determine the direction of causation based on our data.

Furthermore, we observed a significant relationship between anxiety due to uncertainty across tertiles of all dimensions of work-related satisfaction, with differences of approximately half a standard deviation in medical care uncertainty. This is also the first study to report such a strong relationship, highlighting the importance of physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in medical care. Again, we cannot establish the direction of causality from this study, but it seems far more likely that higher stress from uncertainty would cause professional dissatisfaction than the opposite.

Finally, the association between anxiety due to uncertainty and work-related satisfaction was stronger for physicians in training. Indeed, higher levels of anxiety due to uncertainty were associated with differences in work-related satisfaction of approximately 1 SD. Two basic explanations may underlie this finding: the amount of uncertainty may decrease as the physician advances in his or her clinical training and accumulates knowledge and clinical skills, or the physician learns to tolerate and cope with clinical uncertainty, as a specific clinical skill. Quite possibly, both explanations may be true. In both cases, clinical training appears to be important as a way of decreasing stress from uncertainty2,31 and its consequences on professional activities. The socio-demographic and professional determinants of medical care uncertainty suggest that dealing with medical care uncertainty can be taught. This is also typically what senior physicians observe with young interns working in medical outpatient clinic during their training program.2,12 Therefore, learning to cope with uncertainty should be an important goal of clinical training and should be regularly assessed with appropriate instruments.

Limitations and Strengths

The main weakness of our study was its cross-sectional design, which precludes a definitive evaluation of temporal precedence and causality of the observed associations. Another limitation was our exclusive reliance on self-reported rating scales, which raises the issue of systematic positive or negative response tendencies. Finally, as our data had been collected in 1998, it is possible to argue that our results may not be applicable today because of changes in medical studies or postgraduate training. We believe that this is unlikely because recent changes did not introduce specific training to deal with medical care uncertainty.

On the positive side, our results were obtained among a large unselected sample of physicians. The participation rate was acceptable, and the large number of respondents allowed us to explore even fairly weak associations with several determinants of uncertainty. Finally, the French translation of the scales, initially developed by Gerrity,7 retained their psychometric properties.

CONCLUSION

We found new correlates of physicians’ reaction to uncertainty in medical care including its relationship with work-related satisfaction. Physicians who were in training experienced the greatest impact of anxiety due to uncertainty on their work-related satisfaction. Incorporating explicit strategies to deal with uncertainty into residency training curricula may be a useful next step2,29 and should be evaluated quantitatively with appropriate measures. Further studies should also concentrate on the link between reactions to uncertainty and patient outcomes to establish to what extent it could affect quality of care, particularly in primary care.

Acknowledgement

Parts of these results have been presented as a poster at the 74th meeting of the Swiss Society of Internal Medicine, May 10–12, 2006 in Lausanne, Switzerland. This study was funded by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (3200-053377). The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the interpretation or analysis of the data, or the approval the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Appendix

References

- 1.Rizzo JA. Physician uncertainty and the art of persuasion. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:1451–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hewson MG, Kindy PJ, Van Kirk J, et al. Strategies for managing uncertainty and complexity. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:481–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Griffiths F, Green E, Tsouroufli M. The nature of medical evidence and its inherent uncertainty for the clinical consultation: qualitative study. BMJ. 2005;330:511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Geller G, Faden RR, Levine DM. Tolerance for ambiguity among medical students: implications for their selection, training and practice. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:619–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Kassirer JP. Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty. A cause of excessive testing. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1489–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Geller G, Tambor ES, Chase GA, Holtzman NA. Measuring physicians’ tolerance for ambiguity and its relationship to their reported practices regarding genetic testing. Med Care. 1993;31:989–1001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gerrity MS, DeVellis RF, Earp JA. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in patient care: a new measure and new insights. Med Care. 1990;28:724–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Pearson SD, Goldman L, Orav EJ, et al. Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians’ risk attitudes make the difference? J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:557–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Poses RM, De Saintonge DM, McClish DK, et al. An international comparison of physicians’ judgments of outcome rates of cardiac procedures and attitudes toward risk, uncertainty, justifiability, and regret. Med Decis Mak. 1998;18:131–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Friedmann PD, Brett AS, Mayo-Smith MF. Differences in generalists’ and cardiologists’ perceptions of cardiovascular risk and the outcomes of preventive therapy in cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:414–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Tubbs EP, Broeckel Elrod JA, Flum DR. Risk Taking and tolerance of uncertainty: implications for surgeons. J Surg Res. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Light D, Jr. Uncertainty and control in professional training. J Health Soc Behav. 1979;20:310–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Atkinson P. Training for certainty. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19:949–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schor R, Pilpel D, Benbassat J. Tolerance of uncertainty of medical students and practicing physicians. Med Care. 2000;38:272–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Beresford EB. Uncertainty and the shaping of medical decisions. Hastings Cent Rep. 1991;21:6–11. [PubMed]

- 16.Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Cook EF, et al. The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Med Decis Making. 1998;18:320–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.van der Weijden T, van Bokhoven MA, Dinant GJ, et al. Understanding laboratory testing in diagnostic uncertainty: a qualitative study in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:974–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Goehring C, Bouvier Gallacchi M, Kunzi B, Bovier P. Psychosocial and professional characteristics of burnout in Swiss primary care practitioners: a cross-sectional survey. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Goldberg R, Boss RW, Chan L, et al. Burnout and its correlates in emergency physicians: four years’ experience with a wellness booth. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:1156–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Lemkau J, Rafferty J, Gordon R, Jr. Burnout and career-choice regret among family practice physicians in early practice. Fam Pract Res J. 1994;14:213–22. [PubMed]

- 21.Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, et al. Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet. 1996;347:724–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gerrity M, White KP, DeVellis RF, Dittus RS. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty: refining the constructs and scales. Motiv Emot. 1995;19:175–91. [DOI]

- 24.Gerrity M, Earp JA, DeVellis RF, Light DW. Uncertainty and professional work: perceptions of physicians in clinical practice. Am J Sociol. 1992;97:1022–51. [DOI]

- 25.Bovier P, Perneger T. Predictors of work satisfaction among physicians. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Konrad TR, Williams ES, Linzer M, et al. Measuring physician job satisfaction in a changing workplace and a challenging environment. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999;37:1174–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74:829–36. [DOI]

- 28.Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998;316:1236–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Hall KH. Reviewing intuitive decision-making and uncertainty: the implications for medical education. Med Educ. 2002;36:216–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Bovier PA, Martin DP, Perneger TV. Cost-consciousness among Swiss doctors: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Fargason CA, Jr., Evans HH, Ashworth CS, Capper SA. The importance of preparing medical students to manage different types of uncertainty. Acad Med. 1997;72:688–92. [DOI] [PubMed]