Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including both traditional nonselective NSAIDs and the selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, are widely used for their anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. NSAIDs are a necessary choice in pain management because of the integrated role of the COX pathway in the generation of inflammation and in the biochemical recognition of pain. This group of drugs has recently come under scrutiny because of recent focus in the literature on the various adverse effects that can occur when applying NSAIDs. This review will provide an educational update on the current evidence of the efficacy and adverse effects of NSAIDs. It aims to answer the following questions: (1) are there clinically important differences in the efficacy and safety between the different NSAIDs, (2) if there are differences, which are the ones that are more effective and associated with fewer adverse effects, and (3) which are the effective therapeutic approaches that could reduce the adverse effects of NSAIDs. Finally, an algorithm is proposed which delineates a general decision-making tree to select the most appropriate analgesic for an individual patient based on the evidence reviewed.

Keywords: Analgesics, COX-2 specific inhibitors, NSAIDs, Pain

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most widely used medications in the world because of their demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain and inflammation.1 Their efficacy has been documented in a number of clinical disorders, including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, gout, dysmenorrhea, dental pain and headache.2–8 The basic mode of action is inhibition of the pro-inflammatory enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX). NSAIDs as a class comprise both traditional nonselective NSAIDs (tNSAIDs) that nonspecifically inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2, and selective COX-2 inhibitors. Although effective at relieving pain and inflammation, tNSAIDs are associated with a significant risk of serious gastrointestinal adverse events with chronic use.9 Therefore, specific inhibitors of the COX-2 isoenzyme were developed, thus opening the possibility to provide anti-inflammatory and analgesic benefits, while theoretically leaving the gastroprotective activity of the COX-1 isoenzyme intact. However, important concerns have recently been raised regarding the potential cardiovascular toxicity of COX-2 inhibitors.10

This review will provide an educational update of the scientific evidence for the efficacy and adverse effects of NSAIDs in view of the emerging new information for this class of drugs. It is composed deliberately to be a classic, pragmatic review and draws on the results of published systematic reviews and studies regarding the topic. It aims to answer the following questions: (1) are there clinically important differences in the efficacy and safety between the different NSAIDs, (2) if there are differences, which are the ones that are more effective and associated with fewer adverse effects, and (3) which are the effective therapeutic approaches that could reduce the adverse effects of NSAIDs. Finally, an algorithm is proposed which delineates a general decision-making tree to select the most appropriate analgesic for an individual patient based on the evidence reviewed.

A literature search for this review was done by computer in the MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE and CINAHL databases for manuscripts published between 1986 and 2006. A broad free text search with restriction to publications in English was undertaken using all variants of terms “NSAIDs,” “COX-2 inhibitors,” and the names of the common NSAIDs, for example, diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketorolac, naproxen, rofecoxib, valdecoxib and celecoxib. Reference lists of identified articles and pertinent review articles were also manually searched.

Analgesic Efficacy of NSAIDs

The evidence for the effectiveness of NSAIDs is generally overwhelming when the test drug is compared to placebo in acute or chronic pain conditions.11 However, there is a controversy about the relative efficacy of NSAIDs when compared with each other. In the past, some authors have stated that there is little difference in the analgesic efficacy between the different types of NSAIDs.12 Recent evidence has shown that individual NSAIDs do differ in their analgesic efficacy and the Oxford League Table has been suggested as a good tool for assessing the relative efficacy of analgesics.13

There are hundreds of proprietary analgesics in the market with manufacturer’s claims of efficacy. Many physicians and patients are confused as to which analgesic is the most efficacious for the pain that needs to be treated. Frequently, the choice of analgesic is based on personal experience rather than evidence.6,12 The Oxford League Table13 will be used to discuss the relative analgesic efficacy of NSAIDs in this review.

Oxford League Table

The Oxford pain group has constructed the Oxford League Table for analgesics in acute pain by giving each analgesic a number to grade its efficacy.13 The efficacy of analgesics is expressed as the number-needed-to-treat (NNT), the number of patients who need to receive the active drug for one to achieve at least 50% relief of pain compared with placebo over a 4 to 6 hour treatment period.14 The most effective drugs would have a low NNT of approximately 2. This means that for every two patients who receive the drug, one patient will get at least 50% relief due to the treatment (the other patient may or may not obtain relief but it does not reach the 50% level).

Information from the table was from systematic reviews of randomized, double-blind, single-dose studies in patients with moderate to severe pain in postoperative dental, orthopedic, gynecological and general surgical pain. For each review the outcome was identical, that is, at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours. Information is presented in the form of a league table, which has the number of patients in the comparison, the percent with at least 50% pain relief with analgesic, the NNT, and the high and low 95% confidence interval (table 1 ▶).

Table 1.

Oxford League Table.

| Analgesic | Number of patients in comparison | Percent with at least 50% pain relief | NNT | Lower confidence interval | Higher confidence interval |

| Valdecoxib 40 mg | 473 | 73 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| Ibuprofen 800 | 76 | 100 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 2.2 |

| Ketorolac 20 | 69 | 57 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| Ketorolac 60 (intramuscular) | 116 | 56 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| Rofecoxib 50 | 1900 | 63 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Diclofenac 100 | 411 | 67 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| Piroxicam 40 | 30 | 80 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 4.3 |

| Lumiracoxib 400 mg | 252 | 56 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| Paracetamol 1000 + Codeine 60 | 197 | 57 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.9 |

| Oxycodone IR 5 + Paracetamol 500 | 150 | 60 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 3.2 |

| Diclofenac 50 | 738 | 63 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| Naproxen 440 | 257 | 50 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.9 |

| Oxycodone IR 15 | 60 | 73 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 4.9 |

| Ibuprofen 600 | 203 | 79 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 4.2 |

| Ibuprofen 400 | 4703 | 56 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| Aspirin 1200 | 279 | 61 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 3.2 |

| Bromfenac 50 | 247 | 53 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.3 |

| Bromfenac 100 | 95 | 62 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 4.9 |

| Oxycodone IR 10 + Paracetamol 650 | 315 | 66 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 3.5 |

| Ketorolac 10 | 790 | 50 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| Ibuprofen 200 | 1414 | 45 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Oxycodone IR 10+Paracetamol 1000 | 83 | 67 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 5.6 |

| Piroxicam 20 | 280 | 63 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.8 |

| Diclofenac 25 | 204 | 54 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| Dextropropoxyphene 130 | 50 | 40 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 6.5 |

| Pethidine 100 (intramuscular) | 364 | 54 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 3.9 |

| Tramadol 150 | 561 | 48 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 3.6 |

| Morphine 10 (intramuscular) | 946 | 50 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Naproxen 550 | 169 | 46 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 4.8 |

| Naproxen 220/250 | 183 | 58 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 5.2 |

| Ketorolac 30 (intramuscular) | 359 | 53 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 4.9 |

| Paracetamol 500 | 561 | 61 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 13.3 |

| Paracetamol 1500 | 138 | 65 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 9.5 |

| Paracetamol 1000 | 2759 | 46 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 4.4 |

| Oxycodone IR 5 + Paracetamol 1000 | 78 | 55 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 20.0 |

| Paracetamol 600/650 + Codeine 60 | 1123 | 42 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 5.3 |

| Ibuprofen 100 | 396 | 31 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 6.3 |

| Paracetamol 650 + Dextropropoxyphene (65 mg hydrochloride or 100 mg napsylate) | 963 | 38 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 5.6 |

| Aspirin 600/650 | 5061 | 38 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 4.9 |

| Tramadol 100 | 882 | 30 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 6.1 |

| Tramadol 75 | 563 | 32 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 8.2 |

| Aspirin 650 + Codeine 60 | 598 | 25 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 7.4 |

| Oxycodone IR 5 + Paracetamol 325 | 149 | 24 | 5.5 | 3.4 | 14.0 |

| Tramadol 50 | 770 | 19 | 8.3 | 6.0 | 13.0 |

| Codeine 60 | 1305 | 15 | 16.7 | 11.0 | 48.0 |

| Placebo | >10,000 | 18 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Adapted with permission from Bandolier (http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/index.html).

The NNT is useful for comparison of relative efficacy of analgesics since these NNT comparisons are versus placebo. A NNT of 2, which is the best, means that 50 out of 100 patients will get at least 50% relief specifically due to the treatment. Another 20 may have a placebo response giving them at least 50% relief. As an example, ibuprofen 400 mg has a NNT of 2.4 on the league table, therefore approximately 62 (42+20) of 100 patients in total will have effective pain relief. For comparison, 10 mg intramuscular morphine with a NNT of 2.9 will provide approximately 54 (34+20) of 100 patients with effective pain relief.

From the league table, it is clear that tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors do extremely well in this single-dose comparison and that they do differ in efficacy (the differences also reflect the dose response of different doses of selected NSAIDs). At commonly used doses they all have NNT values between 1.6 and 3, and the point estimate of the mean is below that of (i.e., better than) 10 mg of intramuscular morphine (NNT of 2.9), even though the confidence intervals overlap. However, it should be noted that this dose of morphine does not usually last 4 to 6 hours during which pain scores are recorded. tNSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen, and COX-2 inhibitors, such as rofecoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib, top the league table. By comparison, other analgesics such as aspirin 600 mg and acetaminophen 1000 mg (NNT of 4.4 and 3.8, respectively) are significantly less effective than 10 mg intramuscular morphine. The point estimates of the NNT are higher, and there is no overlap of the confidence intervals. Weak opioids perform poorly in single doses on their own. For example, codeine phosphate 60 mg has an NNT of 16.7. However, combining them with simple analgesics improves analgesic efficacy (NNT of 2.2 for acetaminophen 1000 mg + codeine 60 mg).

Limitations of the Oxford League Table

An assumption of the Oxford League Table is that different pain models are comparable, and that the benefit and harm can be extrapolated from one model to another. However, Cooper15 suggested that there are “some clinically relevant differences among the different pain models.” Pooling the data from different procedures and different patient groups by the Oxford pain group may limit their interpretability.16 Even though a direct comparison of efficacy between different drugs is, in principle, a valuable guide to clinical application, creating an average value with a wide margin of error that lacks applicability to particular clinical scenarios may be problematic. For example, a drug that is well-suited to one pain setting may have a different effect or no effect at all in another. Hence, the information provided in the Oxford League Table should be interpreted in light of the specific pain symptoms, which need to be treated, and used as an approximate guide concerning the relative efficacy of analgesics. There remains a need for a league table with NNT calculated related to specific surgical procedures.

Another drawback of the league table is the small size of some trials used to combine the data. Small trials with few patients cannot accurately estimate the magnitude of the analgesic effect. For example, to accurately know the NNT of an analgesic that is 3.0 with a confidence interval of 2.5 to 3.5, about 1000 patients need to be included in a comparative trial. Some drugs meet such stringent criteria. For instance, trials involving 2800 patients were used to combine the data on the league table concerning acetaminophen with an NNT of 3.8. However, for ibuprofen 800 mg, which is at the top of the league table with an impressive NNT of 1.6 and with 100% of patients achieving at least 50% pain relief, only 76 patients were ever involved in the comparative trials. Such disparity in study size necessitates careful interpretation of results.

Comparison of the Efficacy of NSAIDs with Other Analgesics

Older clinical data suggested that acetaminophen is as effective as NSAIDs in many pain conditions.17,18 However, it can be seen from the Oxford League Table that overall, NSAIDs are clearly more efficacious than acetaminophen. A recent survey of 1799 patients with osteoarthritis found that the majority (>60%) preferred NSAIDs over acetaminophen in the symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis based on perceived better efficacy.19 Results from recent blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trials comparing the efficacy of acetaminophen and NSAIDs are consistent with this patient preference for NSAIDs and may necessitate the reassessment of the older clinical data.20,21 Results from a meta-analysis conducted by Lee and colleagues22 indicate that NSAIDs are statistically superior to acetaminophen in reducing osteoarthritis pain. Using data from seven clinical trials that evaluated both tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of osteoarthritis pain, the authors found that scores for overall pain at rest and while walking favored the NSAID group. A second trial, conducted by Zhang and colleagues, 23 found that while acetaminophen was effective in relieving arthritis pain, NSAIDs were significantly better in terms of pain relief, patient preference and clinical response.

While it seems clear that NSAIDs have a better efficacy than acetaminophen, it should be noted that acetaminophen has a safer profile than NSAIDs. A recent Cochrane review of 15 randomized control trials (RCTs) involving 5986 patients comparing the effect of NSAIDs with acetaminophen has concluded that NSAIDs were more effective (significantly better in controlling pain at rest and pain at night with a trend toward superiority in controlling pain after activity).24 However, the risk of adverse gastrointestinal events associated with NSAID use was greater than for acetaminophen, resulting in a benefit-to-risk ratio that favored acetaminophen in certain pain conditions.

It can be seen from the Oxford League Table that few analgesics, if any, are better than NSAIDs for acute pain. All NSAIDs have a NNT of 1.6 to 3.0 on the league table. Alternative analgesics like codeine phosphate 60 mg and tramadol 50 mg, which are commonly used, have an NNT of 16 and 8, respectively. Even parenteral morphine 10 mg and pethidine 100 mg have an NNT of only 2.9.

When the COX-2 inhibitors first appeared on market, some experts suggested that COX-2 inhibitors may have inferior analgesic efficacy compared with tNSAIDs.25,26 However, as more clinical data became available, it became clear that many of the COX-2 inhibitors have equal or better analgesic efficacy compared with tNSAIDs, and this is reflected in the Oxford League Table.13,14,27 In a recent meta-analysis for dental pain, rofecoxib 50 mg (1330 patients) compared with placebo (570 patients) demonstrated a NNT of 1.9 (95% confidence interval 1.8 to 2.1) for 6 hours, 2.0 (1.8 to 2.1) at 8 hours, 2.4 (2.2 to 2.6) at 12 hours, and 2.8 (2.5 to 3.1) at 24 hours.28

Effects of Formulation on the Analgesic Activity of NSAIDs

The formulation of certain NSAIDs can have a profound effect on its efficacy. Certain formulations of NSAIDs may enhance onset of analgesia and efficacy. For example, the absorption of ibuprofen acid is influenced by formulation, and certain salts of ibuprofen (e.g., lysine) and solubilized formulations have an enhanced onset of activity. Ibuprofen lysine 400 mg produces faster onset and higher peak analgesia than a conventional tablet of ibuprofen acid 400 mg in dental pain.29 Solubilized liquigel ibuprofen 400 mg had more rapid onset than acetaminophen 1000 mg and had a longer duration of action than either acetaminophen 1000 mg or ketoprofen 25 mg.30 These differences can be clinically important as the median time to clinically meaningful relief of pain was shorter after solubilized ibuprofen 400 mg than after acetaminophen 1000 mg.31 The solubilized potassium liquigel formulation of ibuprofen is available over-the-counter worldwide. Diclofenac sodium softgel has also been shown to provide a very rapid onset of analgesic activity and prolonged analgesic duration compared with conventional diclofenac potassium.32

Generally, NSAIDs vary in time of onset and duration of analgesic effect. The longer the half-life of the drug, the slower the onset of effect. In addition, a higher dose has a faster onset, higher peak effect and a longer duration. It is advantageous to start with a high dose of a short-life drug (e.g., ibuprofen) and then adjust the dose downward when analgesic efficacy has been achieved. For management of chronic pain, administration of NSAIDs with long half-lives (e.g., naproxen, COX-2 inhibitors) has clear advantages in allowing for once-or twice-a-day dosing. Strict adherence to a treatment schedule that requires drug administration many times a day can be difficult even for the most compliant patient.

Summary Statement

The evidence for the effectiveness of NSAIDs, as compared to placebo in acute pain conditions, is overwhelming and is reflected in the Oxford League Table and in individual reviews. Moreover, individual NSAIDs do differ in their analgesic efficacy. As a group, NSAIDs are excellent analgesics and are even more efficacious than intramuscular morphine for acute pain. However, it should be noted that the evidence for the efficacy of NSAIDs comes mainly from the study of acute pain conditions. There is still a controversy as to which NSAID is better in chronic pain conditions. Two Cochrane reviews of NSAIDs in hip and knee disease are available.33,34 One review focusing on treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip found 43 randomized comparisons, but the lack of standardization of case definition and outcome assessments, together with multiple different comparisons meant that no conclusions could be drawn about which NSAID was best.33 Similarly, the other review could not help us in choosing between NSAIDs for effectiveness in osteoarthritis of the knee.34

Adverse Effects of NSAIDs

NSAIDs are associated with a number of adverse effects. These include alterations in renal function, effects on blood pressure, hepatic injury and platelet inhibition which may result in increased bleeding. However, the most important adverse effects of tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors are the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse effects, respectively.35 The deleterious gastrointestinal effects of tNSAIDs are cause for concern because of their frequency and seriousness. Recent clinical trials have also demonstrated an apparent increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events in patients taking COX-2 inhibitors.10 This section will focus on the evidence of the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse effects of NSAIDs.

Gastrointestinal Risk of tNSAIDs

There are two separate COX gene products, COX-1 and COX-2, that can initiate the metabolism of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and related lipid mediators.32 COX-1 is expressed in most tissues of the body and largely governs the homeostatic production of arachidonic acid metabolites necessary to maintain physiologic integrity, including gastric cytoprotection via prostacyclin (PGI2), whereas COX-2 is induced in response to inflammatory stimuli and is responsible for the enhanced production of eicosanoid mediators for inflammation and pain. All tNSAIDs inhibit COX-2 as well as COX-1 to varying degrees and are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcers observed by endoscopy and serious upper gastrointestinal complications, including gastrointestinal hemorrhage, perforation and obstruction.36–39 The ulcerogenic properties of tNSAIDs to a large extent relate to their capacity to inhibit COX-1 in the gastric mucosa.40 Agents that show less gastrointestinal toxicity tend to be COX-1 sparing (COX-2 selective) and vice versa. Endoscopic studies have demonstrated that gastric or duodenal ulcers develop in 15% to 30% of patients who regularly take tNSAIDs.41 This section will discuss the differences in the gastrointestinal toxicity of the different tNSAIDs and ways to minimize their toxicity.

Relative Risks for Gastrointestinal Toxicity of the Different tNSAIDs

Three recent studies indicate that some tNSAIDs are associated with a higher gastrointestinal risk than others.42–44 The first is a meta-analysis of case-control studies, the second is a cohort study of 130,000 patients over 50 years in the United Kingdom, and the third is a case-control study of 780,000 patients from Italy. These three studies give clear differences in gastrointestinal risks with the different tNSAIDs, and some compounds are clearly associated with higher risks of upper gastrointestinal bleeding than others (table 2 ▶). In general, ibuprofen has the lowest risk among tNSAIDs, while diclofenac and naproxen have intermediate risks, and piroxicam and ketorolac carry the greatest risk. It should be noted that the advantage of “low risk” drugs may be lost once their dose is increased. This information is vital when considering the types of tNSAIDs to prescribe for patients.

Table 2.

Relative risk of gastrointestinal complications with tNSAIDs, relative to ibuprofen or non-use.

| Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

| Drug | Case-control studies42 | Cohort study43 | Case-control44 |

| Nonuse | 1.0 | ||

| Ibuprofen | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.1 (0.6 to 7.1) |

| Fenoprofen | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.5) | 3.1 (0.7 to 13) | |

| Aspirin | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) | ||

| Diclofenac | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.6) | 2.7 (1.5 to 4.8) |

| Sulindac | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.7) | ||

| Diflusinal | 2.2 (1.2 to 4.1) | ||

| Naproxen | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.9) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.5) | 4.3 (1.6 to 11.2) |

| Indomethacin | 2.4 (1.9 to 3.1) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 5.4 (1.6 to 18.9) |

| Tolmetin | 3.0 (1.8 to 4.9) | ||

| Piroxicam | 3.8 (2.7 to 5.2) | 2.8 (1.8 to 4.4) | 9.5 (6.5 to 13.8) |

| Ketoprofen | 4.2 (2.7 to 6.4) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.6) | 3.2 (0.9 to 11.9) |

| Azopropazone | 9.2 (2.0 to 21) | 4.1 (2.5 to 6.7) | |

| Ketorolac | 24.7 (9.6 to 63.5) | ||

Therapeutic Approaches to Reduce Gastrointestinal Toxicity of tNSAIDs

Several strategies may be used to decrease the risk of tNSAID-associated gastrointestinal events. First, gastrointestinal complications can be avoided by the use of non-tNSAID analgesics, when possible (e.g., acetaminophen). Second, use of the lowest effective dose of a tNSAID will decrease the incidence of complications. The analgesic property of tNSAIDs has a ceiling effect (notably, the ceiling dose may be different in acute and chronic pain), meaning that higher doses do not result in enhanced pain control but merely result in more adverse effects. Third, anti-ulcer co-therapy can be used in high risk patients. Finally, the COX-2 inhibitors can be used as an alternative analgesic to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal events. The evidence is summarized in table 3 ▶.

Table 3.

Evidence for reduced gastrointestinal risks with gastroprotective agents.

| Use of Anti-Ulcer Treatments |

| Proton Pump Inhibitor Co-therapy45,46 |

| Two large double-blind placebo RCTs, ASTRONAUT and OMNIUM trials, compared omeprazole (20 mg daily) with standard dose ranitidine (150 mg twice daily) and with misoprostol (200 μg twice daily) in patients with healed ulcers and erosions who continued tNSAID therapy for 6 months post healing. These studies used a composite of surrogate markers (endoscopic ulcers, multiple erosions, and symptoms) as endpoints. In the ASTRONAUT study, the gastric ulcer recurrence rate at 6 months was 5.2% with omeprazole and 16.3% with ranitidine. The percentage of patients with gastric ulcer recurrence in the OMNIUM study was 13% with omeprazole and 10% with misoprostol. |

| Misoprostol Co-therapy48,49 |

| Silverstein study48: 8843 patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving continuous tNSAID therapy were randomly assigned to receive 800 μg of misoprostol or placebo per day. Serious gastrointestinal complications were reduced by 40% (relative risk reduction) among patients receiving misoprostol compared with those receiving placebo. In patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal bleeding, misoprostol conferred a relative risk reduction of 52% and 50%, respectively. |

| Graham study49: 537 patients on long-term tNSAIDs and who had a history of endoscopically documented gastric ulcer were randomized to receive placebo, 800 μg of misoprostol 4 times a day, or 15 or 30 mg of lansoprazole once daily for 12 weeks. Patients receiving lansoprazole (15 or 30 mg) remained free from gastric ulcer longer than those who received placebo (P<0.001) but for a shorter time than those who received misoprostol. By week 12, the percentages of gastric ulcer-free patients were as follows: placebo 51%, misoprostol 93%, 15 mg lansoprazole 80%, and 30 mg lansoprazole 82%. |

| Use of COX-2 Inhibitors |

| Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research (VIGOR) trial54 |

| The study enrolled 8076 patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged 50 years or older to treatment with either rofecoxib 50 mg/day or naproxen 500 mg twice daily. Over 9 months of follow-up the efficacy of rofecoxib and naproxen were equivalent. However, the incidence of confirmed upper gastrointestinal adverse events per 100 patient-years in the rofecoxib group was less than half that observed in the naproxen group. In a post hoc analysis of the trial, about 40% of the gastrointestinal bleeding events were in the lower gastrointestinal tract. These were also reduced by more than half in patients who received rofecoxib. |

| Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study (CLASS)55 |

| In this study 8059 patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis aged 18 years or older were randomly assigned to therapy with celecoxib 400 mg twice daily, ibuprofen 800 mg 3 times daily, or diclofenac 75 mg twice daily. Patients were permitted to receive aspirin if indicated for cardiovascular prophylaxis. During the 6-month treatment period, among patients receiving celecoxib, the annualized incidence of upper gastrointestinal complications alone and in combination with symptomatic ulcers was half that observed in patients who received tNSAIDs. However, this study has been recently criticized because the authors only published the results from the first 6 months of the trial and that unpublished data showed that after 13 months, much of the gastrointestinal benefits had vanished.114 |

| Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET)56 |

| This large scale RCT compared effect of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen for the reduction of gastrointestinal ulcer complications in 18,325 patients with osteoarthritis over 52 weeks. Lumiracoxib showed a 3-fold to 4-fold reduction in ulcer complications compared with tNSAIDs without an increase in the rate of serious CVS events. |

| Successive Celecoxib Efficacy and Safety Study I (SUCCESS-I)57 |

| Another large scale RCT that examined the effect of celecoxib versus diclofenac and naproxen on gastrointestinal outcomes in 13,274 patients with osteoarthritis over 12 weeks. They were equally effective but celecoxib-treated patients had significantly lower rates of any adverse events, including withdrawal due to abdominal pain and serious upper-gastrointestinal events (producing an 8:1 advantage on safety endpoint). |

Use of Anti-Ulcer Co-Therapy

Four classes of drugs, namely proton pump inhibitor (PPI), prostaglandins, histamine H2-blockers and antacids are available for co-therapy for reducing tNSAID-associated gastrointestinal toxicity. Co-therapy with PPIs, which inhibit acid secretion, has been demonstrated in large scale RCTs to promote ulcer healing in patients with tNSAID-related gastric ulcers.45,46 Prophylactic use of PPIs in patients with previous gastrointestinal events or in those at high risk for such events is considered appropriate by major treatment guidelines, but it should be noted that the protective effects of PPIs are confined solely to the gastric mucosa, where it specifically suppresses acid secretion.47 Clinical studies also support the efficacy of misoprostol (a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue) that reduces gastric acid secretion, as a strategy to prevent tNSAID-dependent gastropathy.48,49 However, due to its nonspecific mode of action at the studied dosage (800 μg/day), a significant proportion of patients reported treatment-related adverse events such as diarrhea, and discontinued the medication. It should also be noted that misoprostol increases uterine tonus and is a commonly used drug to terminate pregnancy, which precludes its use in pregnant patients.

To date, there is no definitive evidence that the concomitant administration of histamine H2-blockers or antacids will either prevent the occurrence of gastrointestinal effects or allow continuation of tNSAIDs when such adverse reactions occur.50,51

Histamine H2-blockers decrease the incidence of dyspepsia in patients using tNSAIDs, but at standard doses they appear to have little or no effect on the gastric lesions.52 Moreover, the protective effect of histamine H2-blockers seen in RCTs have not translated well into clinical use.52,53 For example, a recent study shows that using histamine H2-blockers to suppress tNSAID-induced dyspepsia can double the risks of serious gastrointestinal bleeding.51 However, this was an observational cohort study and there may be other confounding factors responsible for the gastrointestinal effects.

Use of COX-2 Inhibitors

Evidence from several large scale RCTs has clearly shown that COX-2 inhibitors have reduced gastrointestinal toxicity as compared to tNSAIDs (table 3 ▶). The VIGOR trial, CLASS trial, TARGET trial and SUCCESS-I trial have provided evidence that COX-2 inhibitors minimize risk for gastrointestinal events.54–57

Clinical studies also suggest that the COX-2 inhibitors are associated with a reduction in risk for gastrointestinal adverse events that is approximately equivalent to the reduction achieved by adding PPI therapy to tNSAIDs.58 Recently released data suggest that, in addition to minimizing ulcers and their complications, COX-2 inhibitors improve the tolerability of anti-inflammatory therapy compared to that achieved with tNSAIDs plus a PPI.59 A multicenter, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of healthy adults that employed video capsule endoscopy found an average of only 0.32 (± 0.10) small bowel mucosal breaks among patients receiving celecoxib 200 mg twice daily compared with 2.99 (± 0.51) for those taking naproxen 500 mg twice daily plus omeprazole 20 mg once daily (P<0.001).60 Similar reductions in gastrointestinal risk were observed with the newer COX-2 inhibitors valdecoxib, etoricoxib and lumiracoxib.61–63

Risk Factors for tNSAID-Induced Gastrointestinal Adverse Events

It should be noted that the risk for serious gastrointestinal complications increases in the following patient groups, necessitating prudent drug choice:64

▪ patients over the age of 65,

▪ patients with a history of previous peptic ulcer disease,

▪ patients taking corticosteroids,

▪ patients taking anticoagulants,

▪ patients taking aspirin.

A recent meta-analysis of 18 case-control and cohort studies published between 1990 and 1999 identified age and previous peptic ulcer disease, particularly if complicated, as the strongest predictors of absolute risk.65

Further, it should be considered that many side effects of tNSAIDs develop in a time-dependent manner, such that “long-term use” should probably be added to the list of risk factors for gastrointestinal adverse effects. In their over-the-counter formulation, tNSAID use is generally advised not to exceed 3 days for fever and 10 days for analgesia; however, considering their widespread use, they have generally proven to be extremely safe.66 Short-term use (5–10 days) of over-the-counter tNSAIDs has been shown in several studies to be extremely safe and well tolerated. Large-scale RCTs and meta-analyses have shown that the side effect profile of over-the-counter naproxen (≤660 mg/day) and ibuprofen (≤1200 mg/day) is no different than that of acetaminophen or placebo.67–70

Summary Statement

Evidence indicates that tNSAIDs do differ in their gastrointestinal toxicity; some associated with higher gastrointestinal risks than others. The lower risk tNSAIDs should be used first and the more toxic tNSAIDs should only be used in the event of a poor clinical response to the less toxic tNSAIDs. As for the therapeutic approaches to reduce gastrointestinal toxicity, the PPIs, misoprostol and COX-2 inhibitors are all effective. However, PPIs and COX-2 inhibitors may be preferable to misoprostol due to their once-daily dosing, and their lower rate of treatment-related adverse events.

Although acetaminophen has a safer gastrointestinal profile than tNSAIDs, there are probably more deaths from acetaminophen than ibuprofen overdose. Acetaminophen overdose can cause fatal hepatotoxicity;71 and severe hepatotoxicity has been reported after therapeutic doses in patients with risk factors such as chronic alcohol consumption, human immunodeficiency virus infection and hepatitis C virus infection.72 Hence, rational prescribing is equally important for “safe” analgesics, like acetaminophen.

Cardiovascular Risks of NSAIDs

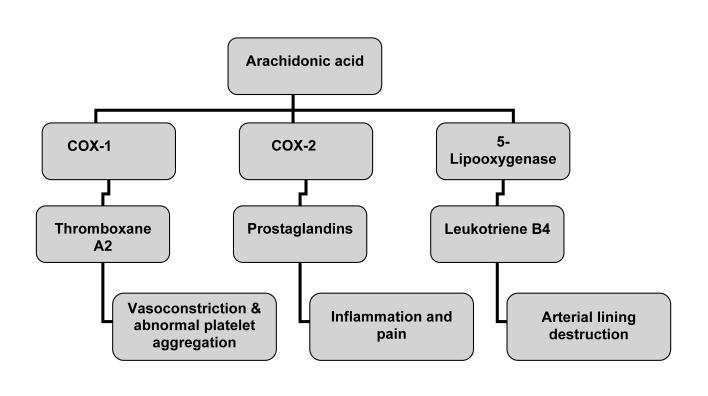

At therapeutic doses, the COX-2 inhibitors are thought to inhibit only the COX-2, but not the COX-1 enzyme. The problem with inhibiting only the COX-2 enzyme is that metabolism imbalances may occur, resulting in an overproduction of harmful byproducts that may damage the arterial wall and induce arterial blood clotting.73 When COX-2 is inhibited, less PGI2 is synthesized from arachidonic acid and more leukotriene B4 and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) are produced. PGI2 is vasodilatory and antiaggregatory, while TXA2 is vasoconstrictive and proaggregatory. This tip of balance allows TXA2 to function unopposed, leading to increased risk for cardiovascular adverse events. Rofecoxib inhibits the COX-2 enzyme 80 times more than the COX-1 enzyme, whereas celecoxib inhibits the COX-2 enzyme only 9 times more than the COX-1.74 (The ratio of COX-2:COX-1 inhibition for the tNSAIDs, ibuprofen and naproxen, is 0.4 and 0.3, respectively.) It can then be extrapolated that rofecoxib shifts the PGI2/TXA2 balance more significantly against PGI2 than other NSAIDs, and hence, is the single agent shown consistently to increase cardiovascular adverse events. These possible harmful mechanisms are illustrated in figure 1 ▶.

Figure 1.

Prostanoid hypothesis for the cardiovascular adverse effects of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors. When COX-2 is inhibited, more leukotriene B4 and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) are produced. This tip of balance leads to an increased risk for cardiovascular adverse events.

A recent study has challenged this prostanoid hypothesis and raises new questions about the mechanisms underlying the potential cardiovascular adverse effects of NSAIDs.75 If the PGI2 and TXA2 imbalance theory holds true then, adding aspirin should eliminate the risk. However, results from other RCTs indicate that adding a COX-1 inhibitor, e.g., aspirin, does not prevent the cardiovascular adverse effects observed with COX-2 inhibitors.55,56 Moreover, if the PGI2/TXA2 hypothesis represented the only mechanistic explanation for these events, one would have expected the use of tNSAIDs (which have considerable COX-1 effects) to be associated with little cardiovascular effects. However, the recent observation of a trend toward increased cardiovascular events with naproxen when compared with placebo and celecoxib in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT) highlights the need to scrutinize these agents.76

Evidence from several large scale RCTs and epidemiologic studies of structurally distinct COX-2 inhibitors has indicated that such compounds elevate the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke (table 4 ▶).54,77–84 This evidence led to the subsequent worldwide withdrawal of rofecoxib and valdecoxib, recently. Notably, valdecoxib was also withdrawn because of an unexpectedly high number of serious dermatological side effects such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Although, COX-2 inhibitors may increase the risk for cardiovascular events, the risk differs to some degree between individuals, across agents, is dose-related, and varies with the duration of therapy. For example, the APPROVe clinical trial showed that the risk was only apparent after 18 months of continuous intake of rofecoxib.77 Risk is highest among patients receiving the 50 mg dose, is less among patients receiving the 25 mg dose, and is not detected among those receiving 12.5 mg. In some high risk patients (e.g., following coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]), valdecoxib increased the cardiovascular events by 3-fold even in short-term application of only 10 to 14 days.79–81 This increased cardiovascular risk from short-term use of valdecoxib was not observed in patients undergoing general or orthopedic surgeries.85 Some studies suggested that celecoxib and lumiracoxib may have a slightly better safety profile than other COX-2 inhibitors. Because the benefits seem to outweigh potential cardiovascular risks, these two drugs have remained on the market.56,86 Currently, celecoxib, etoricoxib, lumiracoxib, and parecoxib are still available in many countries and were approved for marketing as they fulfilled the requirements for drug registration based on internationally accepted guidelines.

Table 4.

Evidence for the cardiovascular effects of COX-2 inhibitors.

| Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research (VIGOR) Trial54 |

| The study enrolled 8076 patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged 50 years or older to treatment with either rofecoxib 50 mg/day or naproxen 500 mg twice daily. Over 9 months of follow-up, it was found that there was a 5-fold divergence in the incidence of myocardial infarction (20 versus 4 events). This study was not originally designed to assess the incidence of cardiovascular event. |

| Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) trial77 |

| This study found that the long-term use of the rofecoxib at 25 mg/day in 2586 patients with a history of colorectal adenomas was associated with an 1.92-fold increased risk for thrombotic events (myocardial infarction and strokes) first observed after 18 months of therapy. This led to the subsequent worldwide withdrawal of rofecoxib on September 30, 2004. It is interesting to note that a correction of the data analysis published recently shows that this conclusion is not supported by a formal statistical test.115 |

| Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib (APC) Trial78 |

| This study randomly assigned 2035 patients with a history of colorectal neoplasia to placebo or high dose celecoxib (400–800 mg/day) for 3 years. It demonstrated dose related increases in cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction and strokes) with celecoxib. A dose of 400 mg/day of celecoxib increased the risk by 2.5-fold, 800 mg/day increased the risk by 3.4-fold compared with placebo. |

| Clinical Trial of Valdecoxib in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG)79,80,81 |

| CABG is characterized by intense hemostatic activation. Two placebo-controlled studies of valdecoxib, anteceded by its intravenous pro-drug parecoxib, were performed in patients undergoing CABG. Despite their small study sizes (462 and 1636 patients, respectively) and short duration (10 and 14 days of treatment, respectively), a pooled analysis of the two quite similar studies suggests that parecoxib/valdecoxib elevates the combined incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke by 3-fold in this population. |

| Epidemiologic Studies82,83 |

| Graham study82: a nested case-control analysis of data from more than 1.3 million patients and 2.3 person-years of follow-up, found that rofecoxib at doses above 25 mg/day was associated with a 3-fold higher incidence of myocardial infarction and/or cardiac deaths than were recorded among nonusers or remote users of anti-inflammatory drugs. |

| Johnsen study83: a population-based case-control study that enrolled 10,280 cases of first-time hospitalization for myocardial infarction and 102,797 sex- and age-matched non-myocardial infarction population controls. All prescriptions for non-aspirin NSAIDs filled before the date of admission for myocardial infarction were identified using population-based prescription databases. It was found that current and new users of rofecoxib, celecoxib and all classes of non-aspirin NSAIDs had elevated relative risk estimates for myocardial infarction. |

| Meta-Analysis of RCTs84 |

| A recent meta-analysis of 18 RCTs and 11 observational studies of rofecoxib supports the cardiovascular findings of VIGOR. Overall, patients who received rofecoxib in these studies were at a 2.3-fold increased risk for myocardial infarction compared with those receiving placebo or other tNSAIDs. |

To add to the controversies of the cardiovascular adverse effects of COX-2 inhibitors, several recent studies have shown that some COX-2 inhibitors are not associated with an increased cardiovascular risk. The SUCCESS-I trial found no increased cardiovascular risks of celecoxib compared to either diclofenac and naproxen in 13,274 patients with osteoarthritis.57 The TARGET trial found no significant difference in cardiovascular deaths between lumiracoxib and either ibuprofen or naproxen, irrespective of aspirin use, in 18,325 patients with osteoarthritis.56 A recent meta-analysis of 34,668 patients receiving lumiracoxib for ≤1 year of treatment found no evidence of increase in cardiovascular risk compared with naproxen, placebo or all comparators.87

With the recent findings of the cardiovascular adverse effects of the COX-2 inhibitors, a potential safety concern has been raised as to whether the increased cardiovascular events would be a class effect for all NSAIDs. Unfortunately, there are no placebo-controlled RCTs addressing the cardiovascular safety of tNSAIDs, only observational studies, information from basic and human pharmacology, and the previously discussed tNSAID comparator RCTs. For example, preliminary results from a long-term observational study suggest that long-term use of certain tNSAIDs may be associated with an increased cardiovascular risk compared to placebo.88,89 In addition, a recent meta-analysis of 14 observational studies suggests that some tNSAIDs may increase myocardial infarction risks.90 In particular, diclofenac carries a higher risk than other tNSAIDs (as it is more COX-2 selective). This was not the case for naproxen. However, it should be noted that there are usually many confounding factors in observational studies which may also be responsible for the increased cardiovascular events.

Based upon the available data, the Food and Drug Administration has concluded that the increased risk of cardiovascular events may be a class effect for all NSAIDs and recommended that all NSAIDs now carry stronger warnings for adverse side effects, including gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse effects.91 These serious warnings for all NSAIDs may have been exaggerated and definitely, and perhaps needlessly, frightened NSAID users, since the current literature supports the enhanced cardiovascular toxicity of COX-2 inhibitors over tNSAIDs.

Summary Statement

Evidence indicates that COX-2 inhibitors as a group have a small but absolute risk of cardiovascular adverse effects. Due to its widespread use a few years ago, this small proportion translates into a large absolute number of COX-2 inhibitor users developing cardiovascular events. Generally, COX-2 inhibitors are contraindicated in patients with a history of ischemic heart disease, stroke or congestive heart failure and in patients who have recently undergone CABG. The cardiovascular risk appears to be dose related and varies with the duration of therapy. Hence, the smallest effective dose for shortest duration should be used when COX-2 inhibitors are indicated.

It should be noted that the analgesic efficacy of COX-2 inhibitors is excellent as evidenced in the Oxford League Table. All drugs have potential adverse effects and COX-2 inhibitor therapy is necessarily a balance between achieving a therapeutic effect, while causing minimum side effects. One should not forget that an inadequate long-term control of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, smoking and weight excess is more deleterious in terms of cardiovascular mortality than the administration of COX-2 inhibitors.

Drug Interactions of NSAIDs

A key concern is the interaction between aspirin and NSAIDs. Although low-dose aspirin is cardioprotective, evidence suggests that concomitant use with certain NSAIDs (in particular ibuprofen) may reduce its cardioprotective benefits and increase gastrointestinal risk.92,93 It has been shown in a recent study that ibuprofen prevents the irreversible platelet inhibition induced by aspirin. This effect may be responsible for a statistically and clinically significant increase in risk for mortality in users of aspirin plus ibuprofen compared with users of ibuprofen alone. In contrast, sustained exposure to diclofenac, rofecoxib or acetaminophen did not influence the effects of aspirin on platelet function.94,95 To add to the controversy, another study on the effect of ibuprofen in aspirin-treated healthy adult volunteers showed no clinically meaningful loss of cardioprotection of aspirin when over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen were administered.96

The gastroprotective benefit of COX-2 inhibitors is partially or, in some patients, totally lost if aspirin is used for cardiovascular prophylaxis.56,97 In a study conducted by Schnitzer and colleagues,56 18,325 patients aged 50 years or older were randomly assigned to lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily, naproxen 500 mg twice daily or ibuprofen 800 mg 3 times daily for 1 year. Patients were stratified by low dose aspirin use and age. Consistent with the results of previous studies of COX-2 inhibitors, the cumulative incidence of ulcer complications was reduced by 3-fold to 4-fold among patients who received lumiracoxib compared with tNSAIDs, but the reduction was smaller and did not reach statistical significance among patients who received concomitant aspirin.

Recent evidence suggests that gastrointestinal benefits may also be lost in patients who receive warfarin together with NSAIDs. In a nested case-control analysis, Battistella and colleagues98 quantified the gastrointestinal risk in warfarin users treated with tNSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors. During the study period, 361 (0.3%) out of 98,821 elderly patients who had received warfarin were admitted with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. These patients were 1.9-fold more likely to be receiving tNSAIDs, 1.7-fold more likely to be receiving celecoxib and 2.4-fold more likely to be taking rofecoxib than to be taking no NSAIDs before hospitalization.

Concurrent use of NSAIDs and corticosteroids may also increase gastrointestinal risk. In a population-based cohort study of 45,980 patients, Nielsen and colleagues99 found that there was an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding among patients who concurrently used NSAIDs and corticosteroids.

Alternative Analgesics

When tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors are inappropriate analgesics for patients, alternatives are available. However, it is worth noting from the Oxford League Table that few, if any, oral analgesics have a better NNT than NSAIDs for acute pain. Acetaminophen should be used as the first-line alternative in view of its efficacy and safety. Opioids and tramadol may also be used when NSAIDs are unsuitable. However, oral opioids like codeine phosphate and merperidine have been shown to be relatively poor analgesics with NNT as high as 16.7 for codeine. Parenteral morphine has a slightly better NNT of 2.9, but still inferior to tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. Tramadol is also a relatively poor analgesic when compared with NSAIDs (NNT of 8.3 for 50 mg tramadol). Combining analgesics, e.g., acetaminophen 1000 mg and codeine 60 mg, increases its efficacy from a NNT of 3.8 and 16.7 for each individual drug, respectively, to a NNT of 2.2 for the combination.13

Nitric oxide releasing NSAIDs are a new class of anti-inflammatory agents obtained by adding a nitric oxide releasing moiety to existing NSAIDs. Preclinical and clinical studies suggest that nitric oxide-NSAIDs inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 activities while causing less adverse effects on the gastrointestinal tract, as compared to tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, and reduce systemic blood pressure.100,101 However, these new drugs have yet to be approved.

It is a common belief that parenteral NSAIDs would be more efficacious than the oral route. Many doctors use injected or rectal NSAIDs even when the oral route can be used. Reasons for choosing these routes are pharmacokinetic based, that is rate of drug absorption may impact upon efficacy and onset of analgesia. A recent meta-analysis compared the analgesic efficacy of NSAIDs given by different routes in acute and chronic pain. Twenty-six RCTs (2225 analyzed patients), published between 1970 to 1996, were reviewed.102 The authors concluded that there is lack of evidence for any difference in analgesic efficacy of NSAIDs given by different routes. However, the intramuscular and rectal routes were more likely to have specific local adverse effects. The intravenous route was also reported to increase the risk of postoperative bleeding. In addition, the parenteral route has the same risks of gastrointestinal toxicity as the oral route. The only possible exception are NSAIDs given by the topical route which are not associated with any of the gastrointestinal effects seen with other routes.103 In view of this evidence, the oral route should be used whenever possible.

Current Recommendations for the Use of NSAIDS

The evidence for the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse effects of NSAIDs have substantial implications for public health, patient education and therapeutic decision making on the part of physicians charged with managing pain-related conditions. A few organizations have published guidelines on the use of tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors.104,105 Generally, any recommendations should offer effective pain control along with optimal gastroprotection, together with an assessment of cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks before initiation of tNSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors therapy.

The Food and Drug Administration expert advisory committee recommends that:106

▪ when COX-2 inhibitors and tNSAIDs are to be used for the management of individual patients, they should be prescribed with the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration.

▪ they should not be prescribed for high risk patients, e.g., patients with a history of ischemic heart disease, stroke or congestive heart failure, or in patients who have recently undergone CABG.

▪ all prescription-strength NSAIDs will now display “black box” label warnings for the potential risk of cardiovascular and gastrointestinal adverse effects.

▪ treatment with tNSAIDs alone in patients aged less than 65 years who do not have gastrointestinal risk factors is considered appropriate. Co-therapy with a PPI or treatment with a COX-2 inhibitor was considered unnecessary in these patients.

▪ the use of a tNSAID alone was considered inappropriate in any patient with a previous gastrointestinal event and in those who concurrently receive aspirin, steroids or warfarin. These patients should receive either a tNSAID plus a PPI or a COX-2 inhibitor.

▪ use of a COX-2 inhibitor with PPI co-therapy is appropriate only in patients at very high risk, such as those with a previous gastrointestinal event who are taking aspirin, and those who are taking aspirin plus steroids or warfarin.

An Algorithm for Decision Making in Pain Management

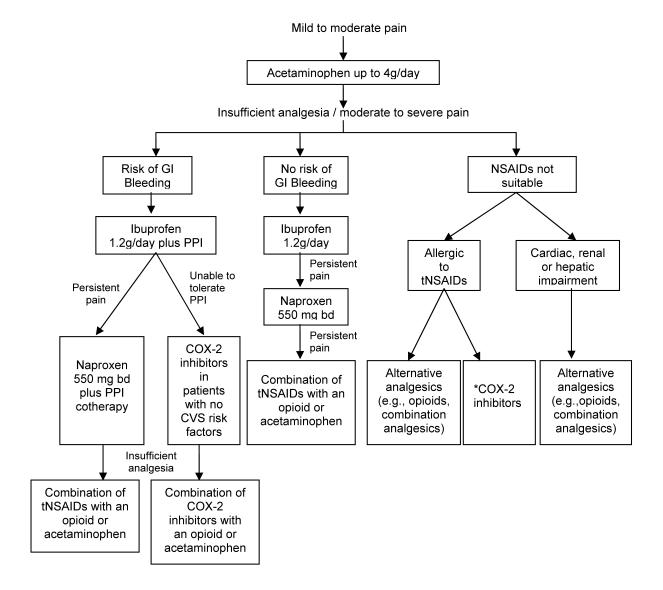

An algorithm for decision making in pain management based on the evidence reviewed and an understanding of the mechanisms of action of this class of drugs is proposed (figure 2 ▶). Selecting the appropriate therapy that provides good pain relief, minimizes cardiovascular risks and preserves the gastrointestinal mucosa is a complex challenge. Factors to consider include (1) the possible interference of certain NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, with the antiplatelet effects of aspirin; (2) direct effects of tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors on fluid retention and blood pressure; (3) emerging data about cardiovascular risks associated with these drugs (particularly with COX-2 inhibitors); (4) differences in the adverse gastrointestinal event rates among tNSAIDs; and (5) the feasibility of co-therapy with gastroprotective agents. Participation in the decision making process by a fully informed patient is an essential element of good medical practice and is recommended.

Figure 2.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) pain management algorithm. Proceed down the algorithm on the basis of pain control and risk factors. Ibuprofen and naproxen are recommended on the basis of extensive evidence supporting efficacy and safety. For management of chronic/persistent pain, administration of NSAIDs with long half-lives has clear advantages in allowing for once- or twice-a-day dosing (e.g., naproxen, COX-2 inhibitors). In addition, COX-2 inhibitors do not have an antiplatelet effect which is an advantage in the perioperative period. *Only after assessing their specific tolerability in a properly performed provocation test. Combination analgesics=acetaminophen+opioids.

The algorithm proposed provides only general recommendations. Although ibuprofen has the lowest gastrointestinal risk and is recommended as the first-line NSAID, there are situations when other NSAIDs would be more suitable. For example, if a patient’s compliance is a problem for the treatment of chronic pain, a once or twice daily formulation would be beneficial (e.g., naproxen and COX-2 inhibitors). The COX-2 inhibitors do not impair platelet function and are an advantage when used in the perioperative period compared to tNSAIDs which inhibit platelet aggregation, increasing risks of postoperative bleeding.107 A recent meta-analysis has shown NSAIDs also to have a pre-emptive effect and reduce postoperative analgesic requirements.108 In addition, when used in combination with acetaminophen, NSAIDs act synergistically to improve analgesia.109 Another recent meta-analysis has shown that this combination can reduce postoperative opioid requirements.110 Hence, it is clear that NSAIDs could provide enormous benefit to the pain patients.

Of particular interest is that COX-2 inhibitors have been reported to be well tolerated for patients with tNSAID intolerance.111–113 Most adverse tNSAID-induced respiratory and skin reactions appear to be precipitated by the inhibition of COX-1. This in turn activates the lipo-oxygenase pathway, which eventually increases the release of cysteinyl leukotrienes and causes the observed allergic reactions.111 It has been suggested by some authors that COX-2 inhibitors may safely be used by patients with tNSAIDs intolerance.111–113 However, we recommend that COX-2 inhibitors be used as alternative drugs in patients with tNSAID intolerance only after assessing their specific tolerability in a properly performed provocation test.

Conclusion

Recent literature focuses on the adverse effects that can occur when applying tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. It is worth remembering that these drugs are excellent analgesics and bring huge benefits to many patients who need them. However, the gastrointestinal consequences of tNSAIDs and the cardiovascular events of COX-2 inhibitors are significant and need to be taken into account when prescribing this group of analgesics to patients.

From the evidence reviewed, it can be recommended that acetaminophen should be used as a first-line agent, particularly for mild pain. It is an effective and safe analgesic at therapeutic doses and can be combined with opioid, e.g., codeine, to increase its efficacy. Thereafter the rule would seem to be to use ibuprofen for preference at the lowest effective dose, and with mucosoprotective agents for those at high risk of developing adverse gastrointestinal events. When other tNSAIDs are required, naproxen should be used, as it has intermediate risks of adverse events. Generally, the lower risk tNSAIDs should be used first and the more toxic tNSAIDs should only be used in the event of a poor clinical response to the less toxic agent. COX-2 inhibitors may have a place for high risk patients who could not take anti-ulcer co-therapy and possibly also for patients who have intolerance to tNSAIDs. In cases of insufficient analgesia with a single agent, tNSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors may be combined with acetaminophen or opioids for additional analgesia.

References

- 1.Laine L. Approaches to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the high-risk patient. Gastroenterology 2001;120:594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon LS. Biologic effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1997;9:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Braun J Current evidence for the management of ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic literature review for the ASAS/EULAR management recommendations in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:423–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kean WF, Buchanan WW. The use of NSAIDs in rheumatic disorders 2005: a global perspective. Inflammopharmacology 2005;13:343–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnitzer TJ; American College of Rheumatology. Update of ACR guidelines for osteoarthritis: role of the coxibs. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:S24–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly TP. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in gynecologic practice. Clin Med Res 2003;1:105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ong KS, Seymour RA. Maximizing the safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use for postoperative dental pain: an evidence-based approach. Anesth Prog 2003;50:62–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Ryan RE Jr, Saper J, Silberstein S, Sheftell F. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in alleviating migraine headache pain: three double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Arch Neurol 1998;55:210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ofman JJ, MacLean CH, Straus WL, Morton SC, Berger ML, Roth EA, Shekelle P. A metaanalysis of severe upper gastrointestinal complications of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. J Rheumatol 2002;29:804–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamdani M, Rochon P, Juurlink DN, Anderson GM, Kopp A, Naglie G, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors and naproxen on short-term risk of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQuay HJ, Edwards JE, Moore RA. Evaluating analgesia: the challenges. Am J Ther 2002;9:179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong CK, Seymour RA. Pathogenesis of postoperative oral surgical pain. Anesth Prog 2003;50:5–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxford League Table of Analgesics in Acute Pain. Bandolier Web site. Available at: http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/booth/painpag/Acutrev/Analgesics/Leagtab.html. Accessed April 18, 2006.

- 14.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995;310:452–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper SA. Single dose analgesic studies: the upside and downside sensitivity. In: Max M, Portenoy R, eds. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. New York, NY: Raven Press;1991. 117–124.

- 16.Gray A, Kehlet H, Bonnet F, Rawal N. Predicting postoperative analgesia outcomes: NNT league tables or procedure-specific evidence? Br J Anaesth 2005;94:710–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley JD, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Kalasinski LA, Ryan SI. Comparison of an antiinflammatory dose of ibuprofen, an analgesic dose of ibuprofen, and acetaminophen in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 1991;325:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams HJ, Ward JR, Egger MJ, Neuner R, Brooks RH, Clegg DO, Field EH, Skosey JL, Alarcon GS, Willkens RF, Paulus HE, Russell IJ, Sharp JT. Comparison of naproxen and acetaminophen in a two-year study of treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:1196–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe F, Zhao S, Lane N. Preference for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs over acetaminophen by rheumatic disease patients: a survey of 1,799 patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pincus T, Koch GG, Sokka T, Lefkowith J, Wolfe F, Jordan JM, Luta G, Callahan LF, Wang X, Schwartz T, Abramson SB, Caldwell JR, Harrell RA, Kremer JM, Lautzenheiser RL, Markenson JA, Schnitzer TJ, Weaver A, Cummins P, Wilson A, Morant S, Fort J. A randomized, double-blind, crossover clinical trial of diclofenac plus misoprostol versus acetaminophen in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1587–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geba GP, Weaver AL, Polis AB, Dixon ME, Schnitzer TJ; Vioxx, Acetaminophen, Celecoxib Trial (VACT) Group. Efficacy of rofecoxib, celecoxib, and acetaminophen in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized trial. JAMA 2002;287:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee C, Straus WL, Balshaw R, Barlas S, Vogel S, Schnitzer TJ. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents versus acetaminophen in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Jones A, Doherty M. Does paracetamol (acetaminophen) reduce the pain of osteoarthritis? A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:901–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Judd MG, Catton M, Hochberg MC, Wells G. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD004257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wallace JL, Reuter BK, McKnight W, Bak A. Selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2: are they really effective, selective, and GI-safe? J Clin Gastroenterol 1998;27:S28–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeske AH. Selecting new drugs for pain control: evidence-based decisions or clinical impressions? J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133:1052–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong KS, Seymour RA, Yeo JF, Ho KH, Lirk P. The efficacy of preoperative versus postoperative rofecoxib for preventing acute postoperative dental pain: a prospective randomized crossover study using bilateral symmetrical oral surgery. Clin J Pain 2005;21:536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Individual patient meta-analysis of single-dose rofecoxib in postoperative pain. BMC Anesthesiol 2004;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper SA, Reynolds DC, Gallegos LT, Reynolds B, Larouche S, Demetriades J, STruble WE. A PK/PD study of ibuprofen formulations. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994;55:126. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson NZ, Otero AM, Marrero I, Tirado S, Cooper S, Doyle G, Jayawardena S, Sunshine A. Onset of analgesia for liquigel ibuprofen 400 mg, acetaminophen 1000 mg, ketoprofen 25 mg, and placebo in the treatment of postoperative dental pain. J Clin Pharmacol 2001;41:1238–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Packman B, Packman E, Doyle G, Cooper S, Ashraf E, Koronkiewicz K, Jayawardena S. Solubilized ibuprofen: evaluation of onset, relief, and safety of a novel formulation in the treatment of episodic tension-type headache. Headache 2000;40:561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuniga JR, Phillips CL, Shugars D, Lyon JA, Peroutka SJ, Swarbrick J, Bon C. Analgesic safety and efficacy of diclofenac sodium softgels on postoperative third molar extraction pain. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62:806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Towheed T, Shea B, Wells G, Hochberg M. Analgesia and non-aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Library 1997;4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Watson MC, Brookes ST, Kirwan JR, Faulkner A. Non-aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000142. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Lo V, Meadows SE, Saseen J. When should COX-2 selective NSAIDs be used for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis? J Fam Pract 2006;55:260–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubois RN, Abramson SB, Crofford L, Gupta RA, Simon LS, Van De Putte LB, Lipsky PE. Cyclooxygenase in biology and disease. FASEB J 1998;12:1063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Jick H. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet 1994;343:769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabriel SE, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langman MJ, Weil J, Wainwright P, Lawson DH, Rawlins MD, Logan RF, Murphy M, Vessey MP, Colin-Jones DG. Risks of bleeding peptic ulcer associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet 1994;343:1075–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1888–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laine L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 1996;6:489–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henry D, Lim LL, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Perez Gutthann S, Carson JL, Griffin M, Savage R, Logan R, Moride Y, Hawkey C, Hill S, Fries JT. Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis. BMJ 1996;312:1563–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacDonald TM, Morant SV, Robinson GC, Shield MJ, McGilchrist MM, Murray FE, McDevitt DG. Association of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with continued exposure: cohort study. BMJ 1997;315:1333–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Cattaruzzi C, Troncon MG, Agostinis L. Risk of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with ketorolac, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, calcium antagonists, and other antihypertensive drugs. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhasz L, Racz I, Howard JM, van Rensburg CJ, Swannell AJ, Hawkey CJ. A comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Acid Suppression Trial: Ranitidine versus Omeprazole for NSAID-associated Ulcer Treatment (ASTRONAUT) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;338:719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepanski L, Walker DG, Barkun A, Swannell AJ, Yeomans ND. Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Omeprazole versus Misoprostol for NSAID-induced Ulcer Management (OMNIUM) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;338:727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubois RW, Melmed GY, Henning JM, Laine L. Guidelines for the appropriate use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclo-oxygenase-2-specific inhibitors and proton pump inhibitors in patients requiring chronic anti-inflammatory therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, Davies HW, Struthers BJ, Bittman RM, Geis GS. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graham DY, Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, Haber MM, Collis C, Lukasik NL, Huang B; NSAID-Associated Gastric Ulcer Prevention Study Group. Ulcer prevention in long-term users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, active- and placebo-controlled study of misoprostol vs lansoprazole. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan FK, Graham DY. Review article: prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastrointestinal complications—review and recommendations based on risk assessment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:1051–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh G, Ramey DR, Morfeld D, Shi H, Hatoum HT, Fries JF. Gastrointestinal tract complications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective observational cohort study. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1530–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ehsanullah RS, Page MC, Tildesley G, Wood JR. Prevention of gastroduodenal damage induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: controlled trial of ranitidine. BMJ 1988;297:1017–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koch M, Dezi A, Ferrario F, Capurso I. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal mucosal injury. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2321–2332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, Day R, Ferraz MB, Hawkey CJ, Hochberg MC, Kvien TK, Schnitzer TJ; VIGOR Study Group. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1520–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, Whelton A, Makuch R, Eisen G, Agrawal NM, Stenson WF, Burr AM, Zhao WW, Kent JD, Lefkowith JB, Verburg KM, Geis GS. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA 2000;284:1247–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schnitzer TJ, Burmester GR, Mysler E, Hochberg MC, Doherty M, Ehrsam E, Gitton X, Krammer G, Mellein B, Matchaba P, Gimona A, Hawkey CJ; TARGET Study Group. Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET), reduction in ulcer complications: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh G, Fort JG, Goldstein JL, Levy RA, Hanrahan PS, Bello AE, Andrade-Ortega L, Wallemark C, Agrawal NM, Eisen GM, Stenson WF, Triadafilopoulos G; SUCCESS-I Investigators. Celecoxib versus naproxen and diclofenac in osteoarthritis patients: SUCCESS-I Study. Am J Med 2006;119:255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borer JS, Simon LS. Cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects of COX-2 inhibitors and NSAIDs: achieving a balance. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:S14–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan FK, Hung LC, Suen BY, Wu JC, Lee KC, Leung VK, Hui AJ, To KF, Leung WK, Wong VW, Chung SC, Sung JJ. Celecoxib versus diclofenac and omeprazole in reducing the risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients with arthritis. N Engl J Med 2002;347:2104–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG; Investigators. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Efficacy and safety of valdecoxib for treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Pain 2004;111:286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hunt RH, Harper S, Watson DJ, Yu C, Quan H, Lee M, Evans JK, Oxenius B. The gastrointestinal safety of the COX-2 selective inhibitor etoricoxib assessed by both endoscopy and analysis of upper gastrointestinal events. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1725–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kivitz AJ, Nayiager S, Schimansky T, Gimona A, Thurston HJ, Hawkey C. Reduced incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with lumiracoxib compared with ibuprofen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:1189–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1888–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hernandez-Diaz S, Rodriguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2093–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hersh EV, Moore PA, Ross GL. Over-the-counter analgesics and antipyretics: a critical assessment. Clin Ther 2000;22:500–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Milsom I, Minic M, Dawood MY, Akin MD, Spann J, Niland NF, Squire RA. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of nonprescription doses of naproxen and naproxen sodium with ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and placebo in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: a pooled analysis of five studies. Clin Ther 2002;24:1384–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DeArmond B, Francisco CA, Lin JS, Huang FY, Halladay S, Bartziek RD, Skare KL. Safety profile of over-the-counter naproxen sodium. Clin Ther 1995;17:587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rampal P, Moore N, Van Ganse E, Le Parc JM, Wall R, Schneid H, Verriere F. Gastrointestinal tolerability of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol and aspirin at over-the-counter doses. J Int Med Res 2002;30:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Le Parc JM, Van Ganse E, Moore N, Wall R, Schneid H, Verriere F. Comparative tolerability of paracetamol, aspirin and ibuprofen for short-term analgesia in patients with musculoskeletal conditions: results in 4291 patients. Clin Rheumatol 2002;21:28–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, Reisch JS, Schiodt FV, Ostapowicz G, Shakil AO, Lee WM; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology 2005;42:1364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moling O, Cairon E, Rimenti G, Rizza F, Pristera R, Mian P. Severe hepatotoxicity after therapeutic doses of acetaminophen. Clin Ther 2006;28:755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lenzer J. FDA advisers warn: COX 2 inhibitors increase risk of heart attack and stroke. BMJ 2005;330:440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pitt B, Pepine C, Willerson JT. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition and cardiovascular events. Circulation 2002;106:167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McAdam BF, Byrne D, Morrow JD, Oates JA. Contribution of cyclooxygenase-2 to elevated biosynthesis of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin in cigarette smokers. Circulation 2005;112:1024–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alzheimer’s disease anti-inflammatory prevention trial. ADAPT Web site. Available at: http://www.jhucct.com/adapt/documents.htm. Accessed January 26, 2007.

- 77.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K, Lines C, Riddell R, Morton D, Lanas A, Konstam MA, Baron JA; Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1092–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Wittes J, Fowler R, Finn P, Anderson WF, Zauber A, Hawk E, Bertagnolli M; Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib (APC) Study Investigators. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, Langford RM, Hoeft A, Parlow JL, Boyce SW, Verburg KM. Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ott E, Nussmeier NA, Duke PC, Feneck RO, Alston RP, Snabes MC, Hubbard RC, Hsu PH, Saidman LJ, Mangano DT; Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia (McSPI) Research Group; Ischemia Research and Education Foundation (IREF) Investigators. Efficacy and safety of the cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:1481–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, FitzGerald GA. Parecoxib, valdecoxib, and cardiovascular risk. Circulation 2005;111:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]