Abstract

Polygenic autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In recent years, functionally important genetic polymorphisms conferring susceptibility to SLE have been identified, but the evolutionary pressures driving their retention in the gene pool remain elusive. A defunctioning, SLE-associated polymorphism of the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb is found at an increased frequency in African and Asian populations, broadly corresponding to areas where malaria is endemic. Here, we show that FcγRIIb-deficient mice have increased clearance of malarial parasites (Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi) and develop less severe disease. In vitro, the human lupus associated FcγRIIb polymorphism enhances phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. These results demonstrate that FcγRIIb is important in controlling the immune response to malarial parasites and suggests that the higher frequency of human FcγRIIb polymorphisms predisposing to SLE in Asians and Africans may be maintained because these variants reduce susceptibility to malaria.

Keywords: autoimmunity, evolution, Fcγ receptors

Fcγ receptors bind IgG and may be activatory (FcγRI, IIa, IIIa, IIIb, and IV) or inhibitory (FcγRIIb) (1). FcγRIIb inhibits many features of the immune response, including FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, proinflammatory cytokine production, antigen presentation, and antibody responses (1, 2). Mice deficient in FcγRIIb demonstrate hyperactive immune responses (3) and are prone to autoimmunity (2), particularly systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (4), but show increased resistance to bacterial infections (5). Furthermore, polygenic murine SLE models have a deletion in the FcγRIIb promoter associated with reduced receptor expression on macrophages and activated B cells (6, 7). In humans, a single nucleotide polymorphism in the FcγRIIb gene encodes a threonine for isoleucine substitution at position 232, within the transmembrane domain. FcγRIIbT232 has been found at increased frequency in patients with SLE (8–11) and has defective inhibitory function (12, 13). The frequency of the different FcγRIIb232 genotypes worldwide demonstrates significant geographical variation: FcγRIIbT/T232 is found in 0.7–1% of populations of European origin but is up to 10 times more prevalent in south and east Asian populations (8, 12). Interestingly, the severity and prevalence of SLE is also much higher in these racial groups (14). Given that malarial infection, particularly due to Plasmodium falciparum, is or has been a major cause of death in these geographic areas (15) and that the FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype encodes a nonfunctioning receptor (12, 13), we wished to examine whether FcγRIIb deficiency might protect against malaria. Moreover, FcγRIIb is known to control activatory FcγRs, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of malaria (16, 17). If FcγRIIb deficiency increased pathogen clearance, this could explain the high frequency of SLE-associated mutations and, thus, a predisposition to autoimmunity in Africans and Asians, similar to the effect of malaria on the selection of thalassemia or sickle cell anemia (18, 19).

Results

FcγRIIb232 Genotype in an East African Population.

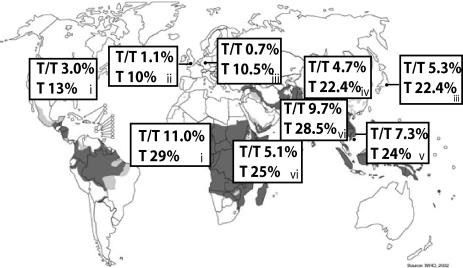

We wished to determine FcγRIIb232 genotypes in an African population. DNA samples from Kilifi, Kenya were obtained, and FcγRIIb sequencing was undertaken. As in south and east Asian populations, the frequency of the SLE-associated FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype and FcγRIIbT232 allele was higher in Kenyans (5.1 and 25%, respectively) than in Europeans (Fig. 1). Li et al. (9) examined FcγRIIb232 genotypes in African-Americans, likely to be of west African origin, and found a higher FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype frequency of 11% and an allele frequency of 29%.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype and FcγRIIbT232 allele frequency in populations worldwide. Data in boxes labeled i obtained from Li et al. (9), box ii from Floto et al. (12), boxes iii from Kyogoku et al. (8), box iv from Chu et al. (11), box v from Siriboonrit et al. (10), and boxes vi by sequencing DNA samples obtained from Kenya (18) or the U.K., demonstrating higher frequency of FcγRIIbT232 allele in areas where malaria is or has been endemic. [Reproduced with permission from ref. 54 (Copyright 2002, WHO).]

FcγRIIb-Deficient Mice Have Reduced Parasitemia and Disease Severity After Malarial Infection.

FcγRIIb-deficient and control mice were infected with the nonlethal murine malarial parasite Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. This parasite was chosen because it is the model most widely used to study the immune response to the erythrocytic stage of infection, in which antibody-mediated phagocytosis and proinflammatory cytokines play an important role in controlling infection (20). FcγRIIb-deficient mice developed lower peak levels of parasitemia [irrespective of the dose of parasite used, Fig. 2A; and at all time points measured, supporting information (SI) Fig. 5A] and demonstrated a more rapid resolution of parasitemia (SI Fig. 5A). In keeping with their reduced parasitemia, FcγRIIb-deficient mice were less severely anaemic (Fig. 2B and SI Fig. 5B); for example, the hematocrit fell by 35% in controls but only 25% in FcγRIIb-deficient mice inoculated with 5 × 106 parasitized erythrocytes (Fig. 2B). Hypothermia has been validated as a marker of disease severity in P. chabaudi chabaudi infection (21) and was significantly less severe in FcγRIIb-deficient mice (Fig. 2C and SI Fig. 5C).

Fig. 2.

P. chabaudi chabaudi infection in control (white) and FcγRIIb-deficient (black) mice. Percent parasitemia (A), fall in hematocrit (B), and temperature (C) 6 and 9 days after inoculation with 5 × 106 (Upper) or 1 × 105 (Lower) P. chabaudi chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes i.p.

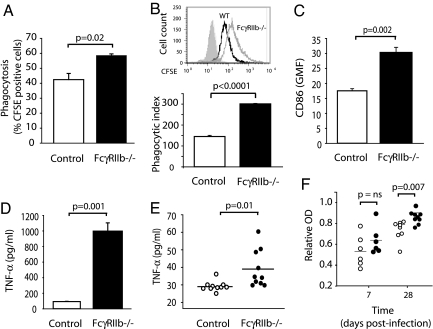

Increased Phagocytosis of Malarial Parasites by FcγRIIb-Deficient Macrophages.

We considered a number of mechanisms to explain the increased parasite clearance and reduced disease severity in FcγRIIb-deficient mice, including FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, proinflammatory cytokine production, and antibody responses. Macrophages are important in the immune response to malaria, both as antigen-presenting cells and phagocytes (22). In particular, FcγR-mediated phagocytosis is critical for the elimination of parasitized erythrocytes in murine malarial models; Fcγ chain-deficient mice demonstrate impaired uptake of antibody-opsonized, infected erythrocytes, increased levels of parasitemia, and heightened susceptibility to Plasmodium berghei XAT (23). Given that FcγRIIb inhibits FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, we wished to determine whether FcγRIIb deficiency altered in vitro phagocytosis of opsonized, parasitized erythrocytes. Higher numbers of FcγRIIb-deficient macrophages took up parasitized erythrocytes (58% versus 42% in control macrophages; Fig. 3A) and more parasitized erythrocytes were engulfed per macrophage in FcγRIIb-deficient mice (Fig. 3B), particularly at later time points (SI Fig. 6). Expression of the costimulatory molecule CD86 on FcγRIIb-deficient peritoneal macrophages after incubation with parasitized erythrocytes was higher than in control macrophages (Fig. 3C), potentially enabling FcγRIIb-deficient macrophages to induce increased activation of T cells during antigen presentation.

Fig. 3.

Macrophage and antibody responses to malarial parasites. Percent phagocytosis (% CFSE-positive macrophages) (A) and phagocytic index (geometric mean fluorescence of CFSE-positive macrophages) (B) in control and FcγRIIb-deficient macrophages after a 40-min incubation with P. chabaudi chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes opsonized with hyperimmune serum. (C) Up-regulation of surface CD86 on control and FcγRIIb-deficient macrophages after an 18-h incubation with P. chabaudi chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes opsonized with hyperimmune serum. (D) TNF-α production by control and FcγRIIb-deficient macrophages after an 18-h incubation with P. chabaudi chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes opsonized with hyperimmune serum. (E) Serum TNF-α levels in control and FcγRIIb-deficient mice 8 days after inoculation with 1 × 105 P. chabaudi chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes. (F) Antimalarial IgG titers in control and FcγRIIb-deficient mice 7 and 28 days after inoculation with 1 × 105 P. chabaudi chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes.

Increased TNF-α Production by FcγRIIb-Deficient Macrophages After Ingestion of Malarial Parasites.

The proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α is important in defense against malaria. For example, TNF-R1-knockout are significantly more susceptible to P. chabaudi chabaudi (21, 24), and TNF-α promotes macrophage phagocytosis (25, 26) and enhances killing of intraerythrocytic P. falciparum in humans (27). Because FcγRIIb-deficient mice produce increased TNF-α in pneumococcal infection (5) and inflammatory alveolitis (28), we examined TNF-α levels after infection with malarial parasites. Peritoneal macrophages from FcγRIIb-deficient mice incubated with serum-opsonized P. chabaudi chabaudi produced significantly more TNF-α than controls (Fig. 3D). In vivo, serum TNF-α levels after primary infection with P. chabaudi chabaudi were significantly higher in FcγRIIb-deficient mice (Fig. 3E).

Increased Anti-malarial Antibody Titers in FcγRIIb-Deficient Mice.

Resolution of primary P. chabaudi chabaudi infection depends on B cells and antibody (29). The importance of antibody in the immune response to the erythrocytic stages of malaria has been demonstrated by the passive transfer of immune IgG in murine (30) and nonhuman primate (31) malarial models and in humans (32). Because FcγRIIb knockout mice generate enhanced antibody responses to both T-dependent and T-independent antigens (3, 5), we examined levels of malaria-specific IgG after infection with P. chabaudi chabaudi. Anti-malarial IgG titers in response to infection were significantly higher in FcγRIIb knockout mice compared with controls (Fig. 3F).

SLE-Associated FcγRIIbT232 Polymorphism in Humans Enhances Phagocytosis of P. falciparum-Infected Erythrocytes.

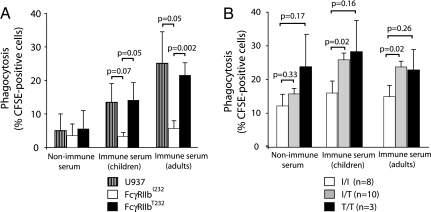

Given that we have shown that FcγRIIb deficiency is associated with heightened parasite clearance and reduced disease severity in mice and others have demonstrated that polymorphisms of an activatory human Fc receptor, FcγRIIa, have been associated with altered susceptibility to malaria in humans (16, 17), we investigated whether defects in FcγRIIb function might alter the response to malarial infection in humans. Exposure to P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes preincubated with nonimmune serum to the FcγRIIb-negative human monocytic cell line U937 or to clones (12) stably expressing equal quantities of either FcγRIIbI232 or the SLE-associated FcγRIIbT232 resulted in low levels of phagocytosis (Fig. 4A). When parasitized erythrocytes were preincubated with serum from immune children or adults, enhanced phagocytosis was observed, but this was markedly reduced in cells expressing FcγRIIbI232 but not FcγRIIbT232 (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained in primary human monocyte-derived macrophages. Regardless of the opsonizing serum used, phagocytosis was inhibited in macrophages derived from subjects with the FcγRIIbI/I232 genotype but not from heterozygotes or subjects with the FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype (Fig. 4B). Because of the low frequency of the FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype in Caucasian populations, only three donors with this genotype were available, making it difficult to achieve statistical significance. Overall, these results demonstrate that individuals expressing the functionally impaired FcγRIIb receptor on phagocytes are better able to clear malarial parasites and may therefore have increased resistance to infection.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of phagocytosis rates (percent of CFSE-positive cells). Phagocytosis rates in differentiated U937 (hatched), FcγRIIbI232 (white), and FcγRIIbT232 (black) cells (A) and phagocytosis rates in monocyte-derived macrophages from subjects with the FcγRIIbI/I232 (white), FcγRIIbI/T232 (gray), and FcγRIIbT/T232 (black) genotype (B) after a 4-h incubation with P. falciparum-parasitized erythrocytes opsonized with nonimmune serum or immune serum obtained from children or adults previously infected with P. falciparum.

Discussion

In this murine malarial model, FcγRIIb deficiency is associated with lower parasitemia, less anemia, and less severe disease. The higher levels of phagocytosis, TNF-α, and anti-malarial antibodies observed in FcγRIIb-deficient mice provide possible mechanisms for this increased resistance to infection. The role of TNF-α is of particular interest because it contributes to both the development of immunity and pathology in malarial infection. High levels of splenic TNF-α correlate with resistance to P. chabaudi chabaudi in inbred strains of mice (33), and TNF-R1-deficient mice have increased levels of parasitemia and more significant recrudescences after primary infection with P. chabaudi chabaudi (21). As mentioned previously, TNF-α enhances macrophage phagocytosis (25, 26) and intraerythrocytic killing of malarial parasites (27); thus the higher levels of TNF-α observed in FcγRIIb-deficient mice may well in part mediate lower levels of parasitemia and reduced disease severity. Deficiency of TNF-R1 in mice is also associated with a lower malaria-specific IgG response, raising the possibility that TNF-α may also contribute to the higher titers of anti-malarial antibodies observed in FcγRIIb-deficient mice. We have previously demonstrated increased TNF-α production in vitro by U937 cells expressing the FcγRIIbT232 compared with FcγRIIbI232 after activatory FcγR cross-linking (12). It may be that individuals either heterozygous or homozygous for the FcγRIIbT232 genotype have heightened levels of TNF-α in vivo after FcγR cross-linking, for example, during phagocytosis of antibody-opsonized parasitized erythrocytes, which might enhance clearance of malarial parasites and antibody production. The latter may be of particular significance given the importance of persistent antibody levels in mediating immunity to recurrent infection. TNF-α has also been implicated in the pathology of malaria. In a murine model of cerebral malaria, P. berghei, TNF-α is crucial for the development of pathology (34). Furthermore, high levels of plasma TNF-α in humans with cerebral malaria secondary to P. falciparum are associated with a worse prognosis (35). Thus, it may be that heightened TNF-α levels in FcγRIIb-deficient mice and in humans with the FcγRIIbT232 receptor protect against mild malarial infections but increase susceptibility to cerebral malaria. This situation would be analogous to the role of FcγRIIb in regulating pneumococcal-associated septic shock (5); however, unimmunized FcγRIIb-deficient mice infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae show increased bacterial clearance and survival after immunization, but on exposure to high innocula of bacteria, these mice produce high levels of TNF-α and IL-6 and have an increased mortality rate. A polymorphism of the gene encoding the activatory Fcγ receptor FcγRIIa, which leads to a histidine or arginine within the extracellular domain of the receptor, significantly alters antibody binding and thus proinflammatory cytokine release in response to Fc receptor cross-linking. Interestingly, the FcγRIIaH/H131 receptor has a higher affinity for IgG2 and IgG3, and individuals with this polymorphism have an increased susceptibility to cerebral malaria (36), supporting the hypothesis that Fc receptor polymorphisms associated with increased proinflammatory cytokine production may increase susceptibility to cerebral malaria.

Phagocytosis of antibody-opsonized antigen is mediated by activatory FcγRs. FcγRIIb inhibits FcγR-mediated phagocytosis (as observed in individuals with the FcγRIIbI/I232 genotype; Fig. 4B), via recruitment of the phosphatase SHIP which dephosphorylates a number of molecules in the activatory FcγR-signaling pathway (37). In contrast, in human monocyte-derived macrophages from individuals with the FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype, there is a failure of such inhibition, and much higher levels of phagocytosis of antibody-opsonized P. falciparum were observed. This observation is consistent with data showing increased phagocytosis of antibody-opsonized pneumococci in these cells and is associated with the exclusion of FcγRIIbT232 from the sphingolipid rafts in which activatory FcγRs are located, rendering FcγRIIbT232 unable to inhibit activatory FcγR signaling (12). Thus, individuals expressing the defunctioned FcγRIIb receptor on phagocytes are better able to clear malarial parasites and may therefore have increased resistance to infection. This resistance would explain the increased frequency of the FcγRIIbT/T232 genotype in populations living in malarial endemic areas. Although malaria affects all age groups, it is the young who bear the brunt of malaria-associated mortality. Therefore, it is likely to act as a powerful evolutionary pressure in determining the selection of immune polymorphisms which confer resistance to infection. Confirmation of this hypothesis with a genetic approach is underway but will be a difficult and protracted process because of the complexity of the region containing FcγRIIb. Gene duplication has resulted in the presence of multiple Fc receptors in this region, making genotyping difficult. Furthermore, there are polymorphisms of FcγRIIa and variable copy numbers of FcγRIIIb (38), both of which are thought to be functionally important and lie in close proximity to FcγRIIb. Once the role of FcγRIIb polymorphisms in malaria is confirmed genetically, it will be possible to examine interactions between polymorphisms in this receptor and other receptors known to be associated with susceptibility to malarial infection, for example, toll-like receptors four and nine (TLR-4 and TLR-9) (39–41).

FcγRIIb deficiency or dysfunction is associated with the development of autoimmunity, particularly SLE, in mice (4, 6, 7) and in humans (12, 13). Given that lupus affects predominantly young females and is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality, the protective effect of the FcγRIIbT232 polymorphism in malarial infection could be offset by a predisposition to autoimmunity. However, the prevalence and severity of autoimmune diseases, particularly lupus, in endemic African populations is low (42, 43) in contrast to Africans living in Western societies (14). The apparent difference may be because of a reporting bias, but a number of lines of evidence suggest that the development of autoimmune diseases in genetically susceptible individuals can be significantly altered by exposure to pathogens. First, the incidence of type 1 diabetes mellitus is lower in children who experience infections before the age of 1 year (44). Second, bacterial and viral infections can modify the severity of collagen-induced arthritis and type 1 diabetes in rodent models of disease; animals maintained in a pathogen-free environment develop more severe disease at earlier time points (45, 46). Diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice can be prevented by mycobacterial (47), viral (48, 49), and parasitic (50, 51) infection. In the murine lupus model NZB/W F1, infection with the murine malarial parasiteP. berghei prevents the development of SLE (52). Furthermore, old NZB/W F1 mice infected with P. chabaudi chabaudi at the onset of clinical signs of lupus develop a remission of autoimmune pathology (53). Thus, malarial infection may alter the development or severity of SLE in individuals with the FcγRIIbT232 polymorphism or other autoimmune-associated polymorphisms.

In summary, our results demonstrate that the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb is important in controlling the immune response to malarial parasites in mice and humans, and suggest that human FcγRIIb polymorphisms predisposing to SLE may be maintained at higher frequencies in endemic areas by reducing susceptibility to malaria.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

FcγRIIb-deficient mice on BALB/c backgrounds (back-crossed for at least eight generations) were kindly provided by J. Ravetch and S. Bolland (The Rockefeller University, New York). All other mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Margate, U.K.).

P. chabaudi chabaudi Infection.

BALB/c FcγRIIb−/− and control mice were infected by i.p. injection of 105 parasitized 129/Sv female-derived erythrocytes. The course of infection was monitored by Giemsa-stained blood films on days 5, 7, 9, and 15. Hematocrit and temperature were also assessed at indicated time intervals throughout the experimental period.

P. chabaudi chabaudi Phagocytosis Assay.

Peritoneal macrophages were adhered to plastic in RPMI medium 1640 containing 10% FCS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C for 2 h, washed, and resuspended in serum-free RPMI medium 1640. Parasitized erythrocytes were harvested from infected mice at day 7, when parasites were at the late trophozoite stage, passed over a column of CF11 powder to remove leukocytes, washed three times in HBSS (Gibco, Paisley, U.K.) containing 10% FCS and labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE). CFSE-labeled erythrocytes were opsonized by incubating with hyperimmune serum (from mice that had survived more than five challenges of P. chabaudi chabaudi infection) at a 1:10 dilution for 30 min at 37°C. After opsonization, CFSE-labeled parasites were incubated with macrophages for 40 min or 18 h at 37°C, before washing and harvesting. Macrophage phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry (FACScalibur; Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA).

CD86 Expression.

CD86 expression in peritoneal macrophages was assessed after an 18-h incubation with P. chabaudi chabaudi-parasitized erythrocytes opsonized with hyperimmune serum by using a PE-labeled rat anti-mouse CD86 antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA).

Cytokine Quantification.

TNF-α levels in serum and macrophage culture supernatant were measured by using a Cytometric Bead Array (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturers instructions. Two color cytometric analysis was performed by using a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data were acquired and analyzed by using BD Cytometric Bead Array software.

Malaria-Specific Antibody Responses.

Serum samples were collected from FcγRIIb−/− and wild-type mice before infection and at days 7 and 28 after primary infection with P. chabaudi chabaudi. Malaria-specific antibodies were determined by ELISA in the following way; a lysate of P. chabaudi chabaudi parasites was used as a source of antigen for the plate coat. The lysate was diluted 1:250 in PBS and applied to 96-well plates (Maxisorp; Nunc, Neerijse, Denmark) overnight at 4°C. The plate coat was washed with PBS/0.05% Tween 20, and serum samples were applied. A control, hyperimmune serum sample from mice that had survived more than five challenges of P. chabaudi chabaudi infection was used as a positive control and standard. Serial dilutions of samples in PBS were performed. Test samples were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed three times in PBS/0.05 Tween 20, and an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was added (1:100 dilution; 50 μl per well) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were revealed by using 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured after 15 min in an ELISA spectrophotometer. Antibody titers are expressed relative to the control hyperimmune serum sample.

P. falciparum.

The laboratory line 2B2, an ITG-derived clone, was grown in culture according to standard procedures. Trophozoites were enriched to >90% purity by using Miltenyi CS columns and magnet. Purified trophozoites were labeled with 0.5 mM CFSE for 5 min at room temperature and washed four times in culture medium. For 1 h, 3 × 106 trophozoites were incubated with 500 ml of a 1:2 dilution in PBS/5 mM EDTA of either pooled nonimmune European serum (EU), pooled immune serum from children, or pooled immune serum from adults resident in Kilifi, Kenya, and washed twice after incubation.

P. falciparum Phagocytosis in U937 Cells.

U937 cells were differentiated into macrophage-like cells by sequential incubation with PMA (1 μM for 3 days) and, after 3 days of recovery, granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) (100 ng/ml for 3 days). In flat-bottom 96-well plates, 3 × 105 P. falciparum serum-opsonized trophozoites were cocultured with differentiated U937 cells for 4 h at 37°C or 4°C in triplicate. Erythrocytes were lysed by using BD Optilyse solution and the percentage of macrophages containing CFSE-labeled trophozoites was determined by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson). The percentage of phagocytosis was calculated by subtracting the mean value of CFSE-positive macrophages at 4°C from the mean value of CFSE-positive macrophages at 37°C.

Primary Cell Purification and Culture.

Peripheral blood from FcγRIIbI/I232, FcγRIIbI/T232, and FcγRIIbT/T232 volunteers was subjected to Ficoll–Hypaque density separation to isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells from which monocytes were enriched by negative selection by using a MACs-based monocyte purification kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Macrophages were generated by culturing the monocytes for 7 days with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (400 ng/ml) in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated autologous serum. Nonadherent cells were discarded before experiments.

P. falciparum Phagocytosis in Primary Human Macrophages.

Peripheral blood from FcγRIIbI/I232, FcγRIIbI/T232, and FcγRIIbT/T232 volunteers was subjected to Ficoll–Hypaque density separation to isolate PBMC from which monocytes were enriched by negative selection by using a MACs-based monocyte purification kit (Miltenyi). Macrophages were generated by culturing the monocytes for 7 days with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (400 ng/ml) in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated autologous serum. Nonadherent cells were discarded before experiments. Phagocytosis was assessed by incubation of cells at 37°C with 3 × 105 serum-opsonized P. falciparum trophozoites for 4 h at 37°C or 4°C in triplicate in flat bottom 96-well plates. Erythrocytes were lysed by using BD Optilyse solution and the percentage phagocytosis determined as described for U937 cells.

Genotyping.

The transmembrane domain of FCGR2B was sequenced by using genomic DNA from 473 Kenyan children (17), U.K. blood donors of Indian or Pakistani descent, and the following primers; forward 5′-AAGGGGAGCCCTTCCCTCTGTT-3′ and reverse 5′-CATCACCCACCATGTCTCAC-3′. The PCR products were purified by using an exonuclease I and shrimp alkaline phosphatase reaction and then sequenced from both directions by using a Big Dye v3 reaction, analyzed on an ABI 3100 sequencer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and donors of the National Blood Service Cambridge Apheresis Clinic and to Vicky Harrison at the National Institute for Medical Research, London for assistance with the mouse work. M.R.C was supported by Wellcome Trust Clinical Training Fellowship 065770, L.W. by an MRC Clinical Training Fellowship, R.A.F. by an Academy of Medical Sciences/Medical Research Council Clinical Scientist Fellowship, and K.G.C.S. by Wellcome Research Leave Award for Clinical Academics 016753AIA. This paper is published with the permission of the director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Abbreviation

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetatesuccinimidyl ester.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0608889104/DC1.

References

- 1.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Immunity. 2006;24:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takai T. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:580–592. doi: 10.1038/nri856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takai T, Ono M, Hikida M, Ohmori H, Ravetch JV. Nature. 1996;379:346–349. doi: 10.1038/379346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolland S, Ravetch JV. Immunity. 2000;13:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clatworthy MR, Smith KGC. J Exp Med. 2004;199:717–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pritchard NR, Cutler AJ, Uribe S, Chadban SJ, Morley BJ, Smith KGC. Curr Biol. 2000;10:227–230. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiu Y, Nakamura K, Abe M, Li N, Wen XS, Jiang Y, Zhang D, Tsurui H, Matsuoka S, Hamano Y, et al. J Immunol. 2002;169:4340–4346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyogoku C, Dijstelbloem HM, Tsuchiya N, Hatta Y, Kato H, Yamaguchi A, Fukazawa T, Jansen MD, Hashimoto H, van de Winkel JG, et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1242–1254. doi: 10.1002/art.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Wu J, Carter RH, Edberg JC, Su K, Cooper GS, Kimberly RP. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3242–3252. doi: 10.1002/art.11313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siriboonrit U, Tsuchiya N, Sirikong M, Kyogoku C, Bejrachandra S, Suthipinittharm P, Luangtrakool K, Srinak D, Thongpradit R, Fujiwara K, et al. Tissue Antigens. 2003;61:374–383. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu ZT, Tsuchiya N, Kyogoku C, Ohashi J, Qian YP, Xu SB, Mao CZ, Chu JY, Tokunaga K. Tissue Antigens. 2004;63:21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floto RA, Clatworthy MR, Heilbronn KR, Rosner DR, MacAry PA, Rankin A, Lehner PJ, Ouwehand WH, Allen JM, Watkins NA, Smith KGC. Nat Med. 2005;11:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/nm1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kono H, Kyogoku C, Suzuki T, Tsuchiya N, Honda H, Yamamoto K, Tokunaga K, Honda Z. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2881–2892. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molokhia M, McKeigue P. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:115–125. doi: 10.1186/ar76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter R, Mendis KN. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:564–594. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.564-594.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi YP, Nahlen BL, Kariuki S, Urdahl KB, McElroy PD, Roberts JM, Lal AA. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:107–111. doi: 10.1086/320999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooke GS, Aucan C, Walley AJ, Segal S, Greenwood BM, Kwiatkowski DP, Hill AV. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams TN, Wambua S, Uyoga S, Macharia A, Mwacharo JK, Newton CR, Maitland K. Blood. 2005;106:368–371. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aidoo M, Terlouw DJ, Kolczak MS, McElroy PD, ter Kuile FO, Kariuki S, Nahlen BL, Lal AA, Udhayakumar V. Lancet. 2002;359:1311–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanni LA, Fonseca LF, Langhorne J. Methods Mol Med. 2002;72:57–76. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-271-6:57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C, Langhorne J. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5724–5730. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5724-5730.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevenson MM, Riley EM. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:169–180. doi: 10.1038/nri1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoneto T, Waki S, Takai T, Tagawa Y, Iwakura Y, Mizuguchi J, Nariuchi H, Yoshimoto T. J Immunol. 2001;166:6236–6241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sam H, Su Z, Stevenson MM. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2660–2664. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2660-2664.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockett KA, Awburn MM, Cowden WB, Clark IA. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3280–3283. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3280-3283.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muniz-Junqueira MI, dos Santos-Neto LL, Tosta CE. Cell Immunol. 2001;208:73–79. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riley EM, Wahl S, Perkins DJ, Schofield L. Parasite Immunol (Oxf) 2006;28:35–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clynes R, Maizes JS, Guinamard R, Ono M, Takai T, Ravetch JV. J Exp Med. 1999;189:179–185. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von der Weid T, Honarvar N, Langhorne J. J Immunol. 1996;156:2510–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majarian WR, Daly TM, Weidanz WP, Long CA. J Immunol. 1984;132:3131–3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fandeur T, Dubois P, Gysin J, Dedet JP, da Silva LP. J Immunol. 1984;132:432–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabchareon A, Burnouf T, Ouattara D, Attanath P, Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Chantavanich P, Foucault C, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Druilhe P. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:297–308. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs P, Radzioch D, Stevenson MM. Infect Immun. 1996;64:535–541. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.535-541.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grau GE, Fajardo LF, Piguet PF, Allet B, Lambert PH, Vassalli P. Science. 1987;237:1210–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.3306918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwiatkowski D, Hill AV, Sambou I, Twumasi P, Castracane J, Manogue KR, Cerami A, Brewster DR, Greenwood BM. Lancet. 1990;336:1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omi K, Ohashi J, Patarapotikul J, Hananantachai H, Naka I, Looareesuwan S, Tokunaga K. Parasitol Int. 2002;51:361–366. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(02)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cox D, Dale BM, Kashiwada M, Helgason CD, Greenberg S. J Exp Med. 2001;193:61–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aitman TJ, Dong R, Vyse TJ, Norsworthy PJ, Johnson MD, Smith J, Mangion J, Roberton-Lowe C, Marshall AJ, Petretto E, et al. Nature. 2006;439:851–855. doi: 10.1038/nature04489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coban C, Ishii KJ, Kawai T, Hemmi H, Sato S, Uematsu S, Yamamoto M, Takeuchi O, Itagaki S, Kumar N, Horii T, Akira S. J Exp Med. 2005;201:19–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mockenhaupt FP, Cramer JP, Hamann L, Stegemann MS, Eckert J, Oh NR, Otchwemah RN, Dietz E, Ehrhardt S, Schroder NW, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:177–182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506803102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mockenhaupt FP, Hamann L, von Gaertner C, Bedu-Addo G, von Kleinsorgen C, Schumann RR, Bienzle U. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:184–188. doi: 10.1086/505152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenwood BM. Lancet. 1968;2:380–382. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90595-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenwood BM, Herrick EM, Voller A. Proc R Soc Med. 1970;63:19–20. doi: 10.1177/003591577006300107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKinney PA, Okasha M, Parslow RC, Law GR, Gurney KA, Williams R, Bodansky HJ. Diabet Med. 2000;17:236–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Like AA, Guberski DL, Butler L. Diabetes. 1991;40:259–262. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breban MA, Moreau MC, Fournier C, Ducluzeau R, Kahn MF. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993;11:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martins TC, Aguas AP. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:248–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oldstone MB, Ahmed R, Salvato M. J Exp Med. 1990;171:2091–2100. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.6.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilberz S, Partke HJ, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Herberg L. Diabetologia. 1991;34:2–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00404016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooke A, Tonks P, Jones FM, O'Shea H, Hutchings P, Fulford AJ, Dunne DW. Parasite Immunol (Oxf) 1999;21:169–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imai S, Tezuka H, Fujita K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:1051–1058. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenwood BM, Herrick EM, Voller A. Nature. 1970;226:266–267. doi: 10.1038/226266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hentati B, Sato MN, Payelle-Brogard B, Avrameas S, Ternynck T. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:8–15. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Public Health Mapping Group. Worldwide Malaria Distribution in 2002. [Accessed May 2, 2006];2002 Available at http://gamapserver.who.int/mapLibrary/Files/Maps/malaria_2002.jpg.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.