Abstract

The rates of C H bond activation for various alkanes by [(N–N)Pt(Me)(TFEd3)]+ (N

H bond activation for various alkanes by [(N–N)Pt(Me)(TFEd3)]+ (N  N = Ar

N = Ar N

N C(Me)

C(Me) C(Me)

C(Me) N

N Ar; Ar = 3,5-di-tert-butylphenyl; TFE-d3 = CF3CD2OD) were studied. Both linear and cyclic alkanes give the corresponding alkene-hydride cation [(N–N)Pt(H)(alkene)]+ via (i) rate determining alkane coordination to form a C

Ar; Ar = 3,5-di-tert-butylphenyl; TFE-d3 = CF3CD2OD) were studied. Both linear and cyclic alkanes give the corresponding alkene-hydride cation [(N–N)Pt(H)(alkene)]+ via (i) rate determining alkane coordination to form a C H σ complex, (ii) oxidative cleavage of the coordinated C

H σ complex, (ii) oxidative cleavage of the coordinated C H bond to give a platinum(IV) alkyl-methyl-hydride intermediate, (iii) reductive coupling to generate a methane σ complex, (iv) dissociation of methane, and (v) β-H elimination to form the observed product. Second-order rate constants for cycloalkane activation (CnH2n), are proportional to the size of the ring (k ∼ n). For cyclohexane, the deuterium kinetic isotope effect (kH/kD) of 1.28 (5) is consistent with the proposed rate determining alkane coordination to form a C

H bond to give a platinum(IV) alkyl-methyl-hydride intermediate, (iii) reductive coupling to generate a methane σ complex, (iv) dissociation of methane, and (v) β-H elimination to form the observed product. Second-order rate constants for cycloalkane activation (CnH2n), are proportional to the size of the ring (k ∼ n). For cyclohexane, the deuterium kinetic isotope effect (kH/kD) of 1.28 (5) is consistent with the proposed rate determining alkane coordination to form a C H σ complex. Statistical scrambling of the five hydrogens of the Pt-methyl and the coordinated methylene unit, via rapid, reversible steps ii and iii, and interchange of geminal C

H σ complex. Statistical scrambling of the five hydrogens of the Pt-methyl and the coordinated methylene unit, via rapid, reversible steps ii and iii, and interchange of geminal C H bonds of the methane and cyclohexane C

H bonds of the methane and cyclohexane C H σ adducts, is observed before loss of methane.

H σ adducts, is observed before loss of methane.

Keywords: alkane functionalization, C–H activation, catalysis, organometallic chemistry

The selective activation and functionalization of saturated alkane C H bonds represent important areas of research (1–5). Alkanes are the main constituents of oil and natural gas; hence the ability to efficiently transform alkanes to more valuable products is highly desirable (1, 2). Unfortunately, alkanes are relatively inert at ambient temperatures and pressures, due to their high homolytic bond strengths and very low acidity and basicity (1, 5). Partial oxidations of alkanes (hydroxylation, oxidative coupling, and oxidative dehydrogenation) are among the few processes that could, in principle, provide valuable products (alcohols, higher alkanes, and alkenes, respectively) in thermodynamically favorable transformations, but such reactions are difficult to carry out with high selectivity at high conversion (1, 2, 4). More traditional high-temperature routes often proceed by free radical mechanisms, for which the products derived from alkanes are virtually guaranteed to be more reactive than the alkane itself, placing an inherent constraint on selectivity (2–4).

H bonds represent important areas of research (1–5). Alkanes are the main constituents of oil and natural gas; hence the ability to efficiently transform alkanes to more valuable products is highly desirable (1, 2). Unfortunately, alkanes are relatively inert at ambient temperatures and pressures, due to their high homolytic bond strengths and very low acidity and basicity (1, 5). Partial oxidations of alkanes (hydroxylation, oxidative coupling, and oxidative dehydrogenation) are among the few processes that could, in principle, provide valuable products (alcohols, higher alkanes, and alkenes, respectively) in thermodynamically favorable transformations, but such reactions are difficult to carry out with high selectivity at high conversion (1, 2, 4). More traditional high-temperature routes often proceed by free radical mechanisms, for which the products derived from alkanes are virtually guaranteed to be more reactive than the alkane itself, placing an inherent constraint on selectivity (2–4).

In contrast, low-temperature homogeneous activations of C H bonds need not, and often do not, involve radicals, and may lead to more selective reactions than those promoted by heterogenous catalysts operating at high temperatures. Although many transition metal complexes have been shown to activate C

H bonds need not, and often do not, involve radicals, and may lead to more selective reactions than those promoted by heterogenous catalysts operating at high temperatures. Although many transition metal complexes have been shown to activate C H bonds, the development of a practical catalyst to transform alkanes to value-added products remains elusive (1, 2). The key problem lies in finding a catalyst system that has both adequate reactivity and selectivity while tolerating oxidizing and protic conditions (4, 5).

H bonds, the development of a practical catalyst to transform alkanes to value-added products remains elusive (1, 2). The key problem lies in finding a catalyst system that has both adequate reactivity and selectivity while tolerating oxidizing and protic conditions (4, 5).

In recent years, several oxidation catalysts based on platinum(II), palladium(II), and mercury(II) salts have been shown to functionalize C H bonds, leading to good yields of partially oxidized products (4, 6–8). For example, [(2,2′-bipyrimidine)PtCl2] catalyzes the selective oxidation of methane in fuming sulfuric acid to give methyl bisulfate in 72% one-pass yield at 81% selectivity based on methane (8). This system, although not yet practical, does demonstrate the potential promise of homogeneous catalytic alkane conversion.

H bonds, leading to good yields of partially oxidized products (4, 6–8). For example, [(2,2′-bipyrimidine)PtCl2] catalyzes the selective oxidation of methane in fuming sulfuric acid to give methyl bisulfate in 72% one-pass yield at 81% selectivity based on methane (8). This system, although not yet practical, does demonstrate the potential promise of homogeneous catalytic alkane conversion.

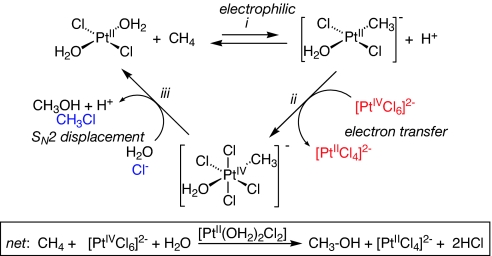

Work in our group has been centered on the Shilov system for selective hydroxylation of alkanes (1, 2, 4). Detailed studies established the three-step mechanism and overall stoichiometry shown in Scheme 1, in which platinum(II) catalyzes the oxidation of alkanes to alcohols by platinum(IV) at 120°C (9–12). Although it is currently impractical because of low reaction rates, expensive oxidant, and catalyst instability, the system does exhibit useful regioselectivity (1° > 2° > 3°) and chemoselectivity.

Scheme 1.

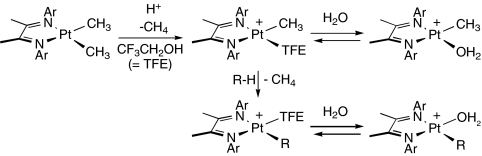

The C H activation step (step i in Scheme 1) is responsible for determining both activity and selectivity; however, direct detailed study of its mechanism is not possible in the “real” Shilov system because of its complexity and interfer-ing side reactions. Accordingly, we turned to model systems, generalized in Scheme 2. The platinum methyl cations[(N

H activation step (step i in Scheme 1) is responsible for determining both activity and selectivity; however, direct detailed study of its mechanism is not possible in the “real” Shilov system because of its complexity and interfer-ing side reactions. Accordingly, we turned to model systems, generalized in Scheme 2. The platinum methyl cations[(N N)Pt(Me)(solv)]+ (N

N)Pt(Me)(solv)]+ (N N=Ar

N=Ar N

N C(Me)

C(Me) C(Me)

C(Me) N

N Ar; solv = TFE = 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol) react with a variety of R-H groups (Ar-H, benzyl-H, indenyl-H, Me3SiCH2-H, etc.) to afford the corresponding organoplatinum products, and have proved to be particularly well suited for mechanistic investigations (13–18). The relative reactivities of chemically differing C

Ar; solv = TFE = 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol) react with a variety of R-H groups (Ar-H, benzyl-H, indenyl-H, Me3SiCH2-H, etc.) to afford the corresponding organoplatinum products, and have proved to be particularly well suited for mechanistic investigations (13–18). The relative reactivities of chemically differing C H bonds are of particular importance for determining selectivity. We report herein on an investigation of the rate and selectivity of C

H bonds are of particular importance for determining selectivity. We report herein on an investigation of the rate and selectivity of C H bond activation for various linear and cyclic alkanes.

H bond activation for various linear and cyclic alkanes.

Scheme 2.

Results

Preparation of [(N–N)Pt(Me)(TFE-d3)]+ (2) and Reactions with Cyclic Alkanes.

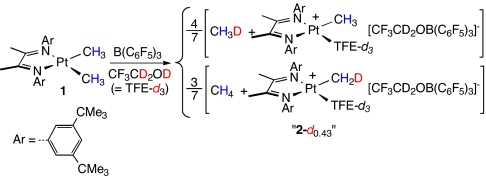

Protonolysis of 1 with B(C6F5)3 in anhydrous TFE-d3 gives platinum(II) monomethyl cation 2, trifluoroethoxytris(pentafluorophenyl)borate, and methane (Scheme 3). Although only 1 equivalent of B(C6F5)3 is required by the stoichiometry of the protonation, 2 equivalents are needed to cleanly generate 2. Both 2 (2-CH3 and 2-CH2D) and the released methane (CH3D and CH4) are obtained as a statistical mixture of isotopologs, the result of fast H/D scrambling among the seven positions of the [(N N)Pt(D)(CH3)2]+ intermediate before methane dissociation (18).

N)Pt(D)(CH3)2]+ intermediate before methane dissociation (18).

Scheme 3.

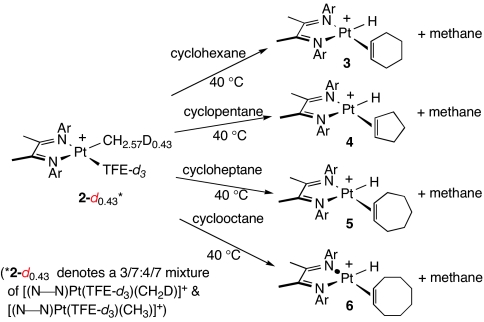

Cyclohexane, cyclopentane, cycloheptane, and cyclooctane react cleanly with the platinum methyl cation 2 at 40°C, as shown in Scheme 4. Addition of cyclohexane to a solution of 2-d0.43 in TFE-d3 produces a single species 3 over the course of several hours. No intermediate platinum species are observed. 1H NMR spectra for 3 support the proposed cyclohexene-hydride formulation,‡ exhibiting in particular a platinum-coordinated olefin peak at δ = 4.9 and a distinctive platinum hydride peak at δ = −22.2 with 195Pt satellites (JPt-H = 1,320 Hz). Cyclopentane, cycloheptane, and cyclooctane all react similarly with 2 to generate the corresponding species 4, 5, and 6 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Kinetics of Cycloalkane C-H Activation by 2.

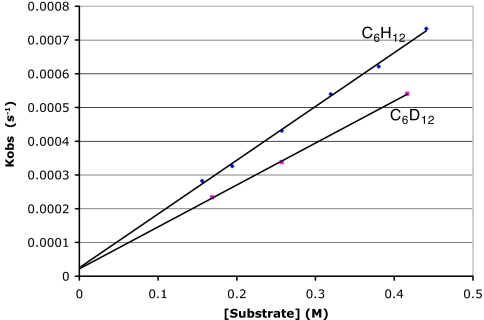

The kinetics for reactions of 2-d0.43 with C6H12 or C6D12 at 40°C were examined by following the disappearance of 2-d0.43 (methyl backbone signal at δ = 2.0) and appearance of 3 by 1H NMR. Reactions displayed clean first-order kinetics for the disappearance of [2] and first- order dependence on [C6H12] (Fig. 1), with k2 = 1.59(4) × 10−3 M−1 s−1. The methane isotopologs CH3D and CH4 were generated in the ratio of ≈1:2. Formation of 3 was accompanied by a much slower background decomposition reaction (18), indicated by both the appearance of additional new 1H NMR signals and the nonzero intercept of Fig. 1 [kdecomp = 2.52(5) × 10−5 s−1]. The rate constant for the reaction of 2-d0.43 with C6D12 at 40°C (Fig. 1) was found to be k2 = 1.24(4) × 10−3 M−1 s−1 [with a similar nonzero intercept, kdecomp = 2.14(8) × 10−5 s−1], corresponding to a kinetic deuterium isotope effect of kH/kD = 1.28(5). Methane isotopologs (CH4, CH3D, CH2D2, CHD3) were observed by 1H NMR in the latter reaction.

Fig. 1.

Plot of kobs vs. [hydrocarbon] for C6H12 (diamonds) and C6D12 (squares) at 40°C.

The kinetics of the reactions of the other cyclic alkanes with 2-d0.43 showed similar behavior (background decomposition rates were somewhat higher) releasing CH3D and CH4 in ≈1:2 ratio, with second-order rate constants k2 = 1.34(20) × 10−3 M−1 s−1 and 1.86(12) × 10−3 M−1 s−1 for cyclopentane and cycloheptane, respectively. The solubility of cyclooctane in TFE is too low to attain pseudo-first-order conditions, precluding a comparably precise determination; an approximate value of k2 = 2.1(5) × 10−3 M−1 s−1 was estimated. In contrast, cyclopropane undergoes rapid C C bond cleavage under these conditions, presumably promoted by the strong Brønsted acidity resulting from the excess of B(C6F5)3 in CF3CD2OD required for clean generation of 2-d0.43 (19).

C bond cleavage under these conditions, presumably promoted by the strong Brønsted acidity resulting from the excess of B(C6F5)3 in CF3CD2OD required for clean generation of 2-d0.43 (19).

Reactions of Linear Alkanes with 2.

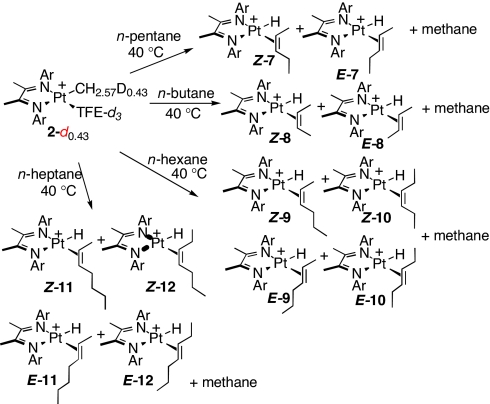

The reaction of n-pentane with 2-d0.43 in TFE-d3 proceeds similarly to those described above: new 1H NMR signals attributable to platinum–olefin–hydride complexes along with CH3D and CH4 (again in a ratio of ≈1:2) grow over several hours at 40°C. However, in this case, the NMR shows clear evidence for two products: platinum hydride signals at δ = −22.2 and −23.3 in an ≈2:1 ratio, respectively, along with two distinct sets of platinum-coordinated olefin peaks. As before, isolation of products was not achieved, and conclusive identification by NMR was not possible; however, addition of excess PMe3 to the reaction mixture after completion displaced coordinated olefins. These were extracted and shown to consist of E-2-pentene and Z-2-pentene in ≈2:1 ratio (gc); no 1-pentene was detected. We conclude therefore that the products of the reaction of n-pentane with 2-d0.43 are the E and Z internal olefin adducts (7-E and 7-Z) formed in a 2:1 ratio (Scheme 5). In a much slower secondary reaction, the mixture of 7-E and 7-Z converts at room temperature over several weeks essentially completely to the Z-2-pentene adduct 7-Z.

Scheme 5.

The reactions of 2-d0.43 with n-butane, n-hexane, and n-heptane proceed similarly but with several additional features. With n-butane, three different Pt-H signals are initially observed, at δ = −22.2, −22.1, and −23.1; the first of these is much weaker than the other two and disappears completely by the time reaction is complete. We ascribe these signals to platinum complexes of 1-butene, E-2-butene, and Z-2-butene, respectively; at the end of the reaction, only the E- and Z-2-butene complexes are present in a 2.5:1 ratio. With both n-hexane and n-heptane, four different platinum hydride signals are observed by 1H NMR. Displacement with PMe3 and gc/ms analysis of the liberated olefins reveals the presence of the four possible internal olefins (E- and Z-2- and 3-enes in each case), indicating that the multiple signals correspond to the four isomeric platinum complexes as shown in Scheme 5. No hydride signal attributable to a 1-alkene adduct was observed with n-pentane, n-hexane, or n-heptane.

Kinetics of C H Activation for Linear Alkanes.

H Activation for Linear Alkanes.

Reactions of 2-d0.43 at 40°C were examined as before, by following the disappearance of 2-d0.43 by 1H NMR at varying excess concentrations of n-alkanes. In all cases pseudo-first-order behavior is observed, rates are first order in alkane concentration, and the ratio of isomers remains relatively constant throughout the course of the reaction. Rate constants at 40°C are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Rate constants for reactions of alkanes with 2

| Substrate | k2* (M−1 s−1) | knorm† |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclopentane | 1.34(20) × 10−3 | 1.34 × 10−4 |

| Cyclohexane | 1.59(4) × 10−3 | 1.33 × 10−4 |

| Cycloheptane | 1.86(12) × 10−3 | 1.33 × 10−4 |

| Cyclooctane | 2.1(5) × 10−3 | 1.31 × 10−4 |

| n-butane | 1.33(4) × 10−3 | 1.33 × 10−4 |

| n-pentane | 1.02(3) × 10−3 | 0.85 × 10−4 |

| n-hexane | 1.06(4) × 10−3 | 0.76 × 10−4 |

| n-heptane | 9.5(18) × 10−4 | 0.59 × 10−4 |

| Methane‡ | 2.7(2) × 10−4 | 0.68 × 10−4 |

Discussion

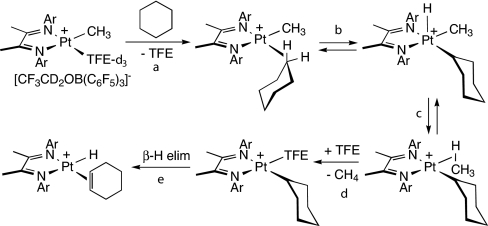

The reactions of linear and cyclic alkane substrates with 2 afford alkene-hydride cations [(N–N)Pt(H)(alkene)]+. The most likely mechanism, based on previous work (ref. 20 and H.A. Zhong, J.A.L., and J.E.B., unpublished) as well as present findings (see below), is shown (for cyclohexane) in Scheme 6. It involves (i) displacement of trifluoroethanol (TFE) by alkane to give a C H σ complex, (ii) oxidative cleavage to a 5-coordinate [PtIV(methyl)(alkyl)(hydride)] intermediate, (iii) reductive coupling to afford a methane C

H σ complex, (ii) oxidative cleavage to a 5-coordinate [PtIV(methyl)(alkyl)(hydride)] intermediate, (iii) reductive coupling to afford a methane C H σ complex, (iv) displacement of methane by TFE, and (v) β-H elimination. Questions of interest include: which step is rate-determining, what is the role and behavior of the proposed C

H σ complex, (iv) displacement of methane by TFE, and (v) β-H elimination. Questions of interest include: which step is rate-determining, what is the role and behavior of the proposed C H σ complex intermediate, and how does reactivity vary with structure?

H σ complex intermediate, and how does reactivity vary with structure?

Scheme 6.

There is precedent for either C H coordination or oxidative C

H coordination or oxidative C H cleavage being rate-determining in alkane activation; a recent theoretical study supports the former (i) as rate-determining in the “real” Shilov system (21). For the reactions of linear and cyclic alkanes with 2, the same conclusion appears to hold. The extensive isotopic scrambling observed for the reaction of 2-d0.43 with C6D12, giving CH2D2 and CHD3 (CD4 is presumably also formed, but not detected by 1H NMR) in addition to the CH3D, and CH4 obtained from reactions of all-protio substrates, indicates that reversible steps iii and iv along with C

H cleavage being rate-determining in alkane activation; a recent theoretical study supports the former (i) as rate-determining in the “real” Shilov system (21). For the reactions of linear and cyclic alkanes with 2, the same conclusion appears to hold. The extensive isotopic scrambling observed for the reaction of 2-d0.43 with C6D12, giving CH2D2 and CHD3 (CD4 is presumably also formed, but not detected by 1H NMR) in addition to the CH3D, and CH4 obtained from reactions of all-protio substrates, indicates that reversible steps iii and iv along with C H bond interchange in cyclohexane and methane C

H bond interchange in cyclohexane and methane C H σ complexes (see below) are all fast relative to loss of methane, consistent with rate-determining C

H σ complexes (see below) are all fast relative to loss of methane, consistent with rate-determining C H coordination. This conclusion is further supported by the small KIE [(kH/kD = 1.28(5)], which is similar to values measured for iridium- and rhodium-based C

H coordination. This conclusion is further supported by the small KIE [(kH/kD = 1.28(5)], which is similar to values measured for iridium- and rhodium-based C H activation systems where C

H activation systems where C H coordination is rate-determining (kH/kD ≈ 1.1–1.4) (22–24), but considerably smaller than values for rate-determining oxidative cleavage of an alkane C

H coordination is rate-determining (kH/kD ≈ 1.1–1.4) (22–24), but considerably smaller than values for rate-determining oxidative cleavage of an alkane C H bond by d8 metal centers (kH/kD ≈ 2.5–5) (25, 26).

H bond by d8 metal centers (kH/kD ≈ 2.5–5) (25, 26).

It is also notable, and consistent with rate-determining C H coordination, that the second-order rate constants for reactions of 2 with cyclic hydrocarbons are roughly proportional to the number of C

H coordination, that the second-order rate constants for reactions of 2 with cyclic hydrocarbons are roughly proportional to the number of C H bonds (Table 1). Bergman and coworkers found that rate constants for the activation of n-alkanes by [Cp*(PMe3)Rh] (Cp* = (η5-C5Me5)) are proportional to the number of secondary (-CH2-) hydrogens in the n-alkane (23). In that system, linear alkanes are more reactive than cycloalkanes (on a per C

H bonds (Table 1). Bergman and coworkers found that rate constants for the activation of n-alkanes by [Cp*(PMe3)Rh] (Cp* = (η5-C5Me5)) are proportional to the number of secondary (-CH2-) hydrogens in the n-alkane (23). In that system, linear alkanes are more reactive than cycloalkanes (on a per C H bond basis). In contrast, for the present system, linear alkanes are less reactive, and the reactivity per C

H bond basis). In contrast, for the present system, linear alkanes are less reactive, and the reactivity per C H bond decreases for longer alkanes. We do not at present have a satisfying explanation for this trend. One possibility is that steric crowding inhibits C

H bond decreases for longer alkanes. We do not at present have a satisfying explanation for this trend. One possibility is that steric crowding inhibits C H coordination in many of the possible conformations accessible to a linear alkane, a problem that should become more severe with increasing chain length but that would not apply to cycloalkanes. However, such reasoning would not explain the low reactivity of methane (Table 1).

H coordination in many of the possible conformations accessible to a linear alkane, a problem that should become more severe with increasing chain length but that would not apply to cycloalkanes. However, such reasoning would not explain the low reactivity of methane (Table 1).

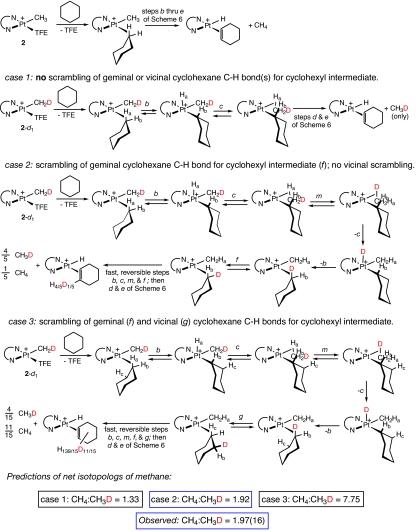

Additional information about the proposed mechanism can be deduced from quantitative details of isotopic scrambling in the methane liberated during reaction with hydrocarbon. Recall that some deuterium is introduced into 2 during the deuterolysis of 1 by (C6F5)3BODCD2CF3 (Scheme 3). When the resulting 4:3 mixture of 2 and 2-d1 reacts with a perprotio substrate, 2 liberates only CH4, whereas 2-d1 releases a mixture of CH3D and CH4. For the latter there are three possible scenarios, illustrated (for the example of cyclohexane) in Scheme 7. In case 1, step b is effectively irreversible; only a single C H bond participates in the reaction, so only CH3D will be generated from 2-d1, and the final ratio of CH4 to CH3D will be 4:3 = 1.33.

H bond participates in the reaction, so only CH3D will be generated from 2-d1, and the final ratio of CH4 to CH3D will be 4:3 = 1.33.

Scheme 7.

In contrast, if steps ii and iii as well the interchange of coordinated C H bonds are reversible and fast, there are two possible cases, depending on how many C

H bonds are reversible and fast, there are two possible cases, depending on how many C H bonds of cyclohexane are sampled before dissociation of methane from the methane σ adduct (step d, Scheme 6). In case 2, there is fast exchange between geminal positions (Ha and Hb of cyclohexane, as well as all positions of coordinated methane); CH3D and CH4 will be generated in a 4:1 statistical ratio with deuterium being retained in the coordinated cyclohexene one-fifth of the time. Summing the methane generated from 2 and 2-d1, the expected ratio of [CH4]:[CH3D] for case 2 is 23:12 = 1.92. For case 3, both geminal and vicinal exchange are fast, so all 12 of the C

H bonds of cyclohexane are sampled before dissociation of methane from the methane σ adduct (step d, Scheme 6). In case 2, there is fast exchange between geminal positions (Ha and Hb of cyclohexane, as well as all positions of coordinated methane); CH3D and CH4 will be generated in a 4:1 statistical ratio with deuterium being retained in the coordinated cyclohexene one-fifth of the time. Summing the methane generated from 2 and 2-d1, the expected ratio of [CH4]:[CH3D] for case 2 is 23:12 = 1.92. For case 3, both geminal and vicinal exchange are fast, so all 12 of the C H bonds of cyclohexane participate in H/D exchange, giving an expected ratio of [CH4]:[CH3D] of 31:4 = 7.75.

H bonds of cyclohexane participate in H/D exchange, giving an expected ratio of [CH4]:[CH3D] of 31:4 = 7.75.

The experimentally observed ratio [CH4]:[CH3D] from the reaction of C6H12 with 2-d0.43 is 1.97(16) for cyclohexane, and approximately the same for all of the other alkanes and cycloalkanes examined. This finding is only consistent with case 2: fast geminal but slow vicinal C H interchange. By way of comparison, in a metastable rhenium–pentane complex (observed at low temperature by NMR) geminal exchange is fast on the NMR time scale, whereas vicinal exchange takes place much more slowly (rates on the order of 1–10 s−1 at 173 K) (27).

H interchange. By way of comparison, in a metastable rhenium–pentane complex (observed at low temperature by NMR) geminal exchange is fast on the NMR time scale, whereas vicinal exchange takes place much more slowly (rates on the order of 1–10 s−1 at 173 K) (27).

For linear alkanes, we have the additional option of coordinating/reacting at either terminal (methyl) or internal (methylene) positions. Jones and coworkers have shown that in a rhodium system (Tp′LRh with L = CNCH2CMe3), coordination of secondary C H bonds is preferred over primary C

H bonds is preferred over primary C H bonds by a factor of 1.5 (27); for the rhenium system cited above, coordination of pentane at the 2- and 3-positions is (very slightly) favored over statistical values (27). We observed a [CH4]:[CH3D] ratio of ≈2:1 for all four linear alkanes, which at first glance seems consistent with statistical scrambling involving only one methylene (-CH2-) group, as with cycloalkanes. However, the predicted [CH4]:[CH3D] ratio for participation of a single terminal methyl (-CH3) group is 15:6 = 2.50; if both primary and secondary C

H bonds by a factor of 1.5 (27); for the rhenium system cited above, coordination of pentane at the 2- and 3-positions is (very slightly) favored over statistical values (27). We observed a [CH4]:[CH3D] ratio of ≈2:1 for all four linear alkanes, which at first glance seems consistent with statistical scrambling involving only one methylene (-CH2-) group, as with cycloalkanes. However, the predicted [CH4]:[CH3D] ratio for participation of a single terminal methyl (-CH3) group is 15:6 = 2.50; if both primary and secondary C H activations occur, the [CH4]:[CH3D] ratio would be between 1.92 and 2.50, well within the uncertainty of this experimental determination.

H activations occur, the [CH4]:[CH3D] ratio would be between 1.92 and 2.50, well within the uncertainty of this experimental determination.

In an attempt to gain further information on this question, we examined the methane produced by reaction of partially deuterated propanes§ (CD3CH2CD3 and CH3CD2CH3) with 2. The former gives CH4 (10%), CH3D (26%), CH2D2 (29%), and CHD3 (35%); exclusive reaction of secondary [C H] bonds would give only CH4 and CH3D, whereas exclusive reaction of primary [C

H] bonds would give only CH4 and CH3D, whereas exclusive reaction of primary [C H] bonds would give no CH4. Similarly, the latter isotopolog gives CH4 (63%), CH3D (32%), and CH2D2 (5%). These results are approximately consistent with statistical expectations; i.e., no preference between terminal and internal positions.

H] bonds would give no CH4. Similarly, the latter isotopolog gives CH4 (63%), CH3D (32%), and CH2D2 (5%). These results are approximately consistent with statistical expectations; i.e., no preference between terminal and internal positions.

The failure to observe any evidence for terminal olefin adducts in the reactions of n-pentane, n-hexane, and n-heptane with 2-d0.43 might also be taken to suggest a preference for internal reaction. However, it seems more likely that the terminal olefin complex is rapidly isomerized to the internal isomers via the olefin insertion/β-H elimination sequence. Such a process has been shown to operate at −78°C on the order of hours in a related [Tp′Pt] system (20), where the initially formed 1-pentene adduct isomerizes to 2-pentene adducts. Our observation of a low transient amount of a terminal alkene adduct only in the case of n-butane (which has a small statistical advantage, relative to higher alkanes, for initial coordination and cleavage of primary C H bonds) is consistent with this interpretation.¶

H bonds) is consistent with this interpretation.¶

Conclusions

We have demonstrated C H bond activation of various alkanes by [(N–N)Pt(Me)(TFE-d3)]+ system to generate [(N–N)Pt(H)(alkene)]+ cations. The small KIE (kH/kD = 1.3) for cyclohexane together with statistical isotopic scrambling in the methane released suggests that C

H bond activation of various alkanes by [(N–N)Pt(Me)(TFE-d3)]+ system to generate [(N–N)Pt(H)(alkene)]+ cations. The small KIE (kH/kD = 1.3) for cyclohexane together with statistical isotopic scrambling in the methane released suggests that C H bond coordination is rate determining. Comparing the relative rates of cyclic and linear alkanes indicates that the platinum center is relatively unselective with respect to different C

H bond coordination is rate determining. Comparing the relative rates of cyclic and linear alkanes indicates that the platinum center is relatively unselective with respect to different C H bonds: the rate constants (per C

H bonds: the rate constants (per C H bond) for the substrates examined all fall into a narrow range, and there does not appear to be any significant preference for either primary or secondary C

H bond) for the substrates examined all fall into a narrow range, and there does not appear to be any significant preference for either primary or secondary C H bonds. Further experimental and computational studies on this point are ongoing.

H bonds. Further experimental and computational studies on this point are ongoing.

Materials and Methods

All air- and/or moisture-sensitive compounds were manipulated by using standard high-vacuum line, Schlenk, or cannula techniques, or in a glove box under a nitrogen atmosphere. B(C6F5)3 was purchased from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and sublimed at 90°C at full vacuum. Trifluoroethanol-d3 was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA) and dried over 3-Å molecular sieves for at least 5 days, then vacuum distilled onto B(C6F5)3, and shortly thereafter distilled into a Strauss flask. All gasses were purchased from Matheson (Joliet, IL) and dried using standard high-vacuum line techniques over 4-Å molecular sieves. CD3CH2CD3 and CH3CD2CH3 were purchased from CND Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada) and dried using standard high-vacuum line techniques. The alkanes were all purchased from Aldrich and dried over calcium hydride. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 spectrometer at 40°C.

For kinetic experiments, stock solutions of 2 were prepared by weighing out 40 mg of 1 and 60 mg of B(C6F5)3. Five milliliters of trifluoroethanol-d3 was then added, and the solution turned light yellow after a few minutes. A total of 0.7 ml of this solution was added to a J-Young NMR tube. The NMR tube was degassed on a high-vacuum line, and an initial 1H NMR spectrum was acquired to confirm complete and clean formation of 2. Alkanes that are liquid at room temperature were then added by syringe and shaken briefly, and the tube was then inserted into an NMR spectrometer that had been preheated to 40°C. Alkanes that are gas at room temperature were vacuum transferred into the NMR tube using standard high-vacuum line techniques. After allowing a few minutes for the NMR tube to reach equilibrium, an array of 40–50 spectra was acquired. Kinetics was monitored by following the disappearance of either one of the backbone methyl peaks or one of the aryl peaks over time. Pseudo first-order rate constants (kobs) were then obtained by fitting the data to a first-order exponential function. Second-order rate constants were then obtained from a plot of kobs vs. [alkane].

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Travis Williams and Bo-Lin Lin for useful discussions and assistance in preparing the manuscript. This work was supported by British Petroleum as part of the Methane Conversion Consortium and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (to G.S.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0610981104/DC1.

We have not yet succeeded in isolating any of these products in pure form: they decompose on concentration, or more slowly on just standing in TFE-d3 solution.

It should be noted, however, that the reactions of propane (and ethane) with 2 do not give olefin-hydride products analogous to those found for higher linear alkanes; these reactions do appear to involve initial C H activation, but the final products exhibit more complex NMR spectra and have not yet been fully identified. Nonetheless, we believe that the inferences from these selective labeling experiments are probably valid.

H activation, but the final products exhibit more complex NMR spectra and have not yet been fully identified. Nonetheless, we believe that the inferences from these selective labeling experiments are probably valid.

There may well be a connection between this behavior and the failure to observe stable olefin-hydride products from propane and ethane (see §), which can give only terminal olefin complexes.

References

- 1.Shilov AE, Shul'pin GB. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2879–2932. doi: 10.1021/cr9411886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Nature. 2002;417:507–514. doi: 10.1038/417507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crabtree RH. Chem Rev. 1995;95:987–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahl SS, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2180–2192. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2180::AID-ANIE2180>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arndtsen BA, Bergman RG, Mobley TA, Peterson TH. Acc Chem Res. 1995;28:154–162. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sen A. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:550–557. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Periana RA, Taube DJ, Evitt ER, Löffler DG, Wentrcek PR, Voss G, Masuda T. Science. 1993;259:340–343. doi: 10.1126/science.259.5093.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Periana RA, Taube DJ, Gamble S, Taube H, Satoh T, Fujii H. Science. 1998;280:560–564. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labinger JA, Herring AM, Lyon DK, Luinstra GA, Bercaw JE, Horvath IT, Eller K. Organometallics. 1993;12:895–905. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luinstra GA, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3004–3005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luinstra GA, Wang L, Stahl SS, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Organometallics. 1994;13:755–756. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutson AC, Lin M, Basickes N, Sen A. J Organomet Chem. 1995;504:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong HA, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1378–1399. doi: 10.1021/ja011189x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stahl SS, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5961–5976. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson L, Tilset M, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10846–10855. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyduk AF, Driver TG, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15034–15035. doi: 10.1021/ja045078k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driver TG, Day MW, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Organometallics. 2005;24:3644–3654. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen JS, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2005–2016. doi: 10.1021/ja056387t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deno NC, LaVietes D, Mockus J, Scholl PC. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:6457–6460. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kostelansky CN, MacDonald MG, White PS, Templeton JL. Organometallics. 2006;25:2993–2998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu H, Ziegler T. J Organometal Chem. 2006;691:4486–4497. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alaimo PJ, Arndtsen BA, Bergman RG. Organometallics. 2000;19:2130–2143. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Periana RA, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:7332–7346. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janowicz AH, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:3929–3939. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northcutt TO, Wick DD, Vetter AJ, Jones WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7257–7270. doi: 10.1021/ja003944x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vetter AJ, Flaschenriem C, Jones WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12315–12322. doi: 10.1021/ja042152q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawes DJ, Geftakis S, Ball GE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4134–4315. doi: 10.1021/ja044208m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]