Abstract

We present previously undescribed spatial group patterns that emerge in a one-dimensional hyperbolic model for animal group formation and movement. The patterns result from the assumption that the interactions governing movement depend not only on distance between conspecifics, but also on how individuals receive information about their neighbors and the amount of information received. Some of these patterns are classical, such as stationary pulses, traveling waves, ripples, or traveling trains. However, most of the patterns have not been reported previously. We call these patterns zigzag pulses, semizigzag pulses, breathers, traveling breathers, and feathers.

Keywords: nonlocal hyperbolic system, signal reception, spatial pattern, zigzag

Pattern formation is one of the most studied aspects of animal communities. Here we present 10 complex spatial patterns that emerge in a one-dimensional mathematical model used to describe the formation and movement of animal groups.

Some of the most remarkable examples of patterns observed in animal groups are related to the behavior displayed by these groups (1). Stationary aggregations formed by resting animals, migrating herds of ungulates, zigzagging flocks of birds, and milling schools of fish are only a few of the patterns. To understand the underlying mechanisms, scientists use mathematical models to simulate these observed biological patterns. The most spectacular examples of group patterns shown by numerical simulations are obtained with individual-based models: swarms, tori, and polarized groups (2, 3). A second mathematical modeling approach is based on continuum models, which are usually described by partial differential equations. In many areas, the continuum models have been successful at deducing conditions that give rise to biological patterns [e.g., morphogenesis (4)], even in one spatial dimension (5). However, this has not been the case for animal grouping models. The one-dimensional continuum models that investigate animal aggregations fail to account for the multitude of complex patterns that one can observe in nature. Generally, the patterns exhibited by these models are simple: local parabolic models do not support traveling waves (6), and nonlocal parabolic models can give rise to stationary pulses (7) or to traveling waves, provided that diffusion is density-dependent (8). Hyperbolic models give rise to ripples (9) and aggregations (9, 10). Considering that one-dimensional models have not explained the complexity of the patterns observed in biological systems, scientists have directed their attention toward two-dimensional models. The results are more complex [e.g., ripples (11), stationary aggregations (7), vortex-like groups (12), patches of aligned individuals (13, 14)], but they still cannot account for the multitude of observed patterns.

One possible reason for this failure is that the assumptions considered by these models do not fully describe the social interactions between individuals governing group formation. More precisely, these models consider that the social interactions depend only on the distances between individuals. However, this assumption might not be sufficient. In support of this statement, we examine a nonlocal mathematical model that focuses on distance-dependent and direction-dependent social interactions, facilitated by animal communication.

The process of formation and movement of animal groups is the result of the interplay between two elements. The first element is represented by the movement-facilitated social interactions, namely movement toward conspecifics or away from them and movement to align with them. Previous models [both individual-based models (2, 3, 15) and continuum models (7, 8)] assume that these interactions are mainly distance-dependent. A few individual-based models (e.g., refs. 2 and 3) take into account that individuals may not receive information from behind because of a so-called “blind spot”. Generally, attraction is considered to act on long ranges, alignment on intermediate ranges, whereas repulsion acts on short ranges. In this paper, we assume that superimposed on these movement-facilitated social interactions, there is a second element: how individuals receive information about conspecifics and the amount of information received. This second element is typically not included in models. However, this approach is reasonable, because there is evidence suggesting that not all animals receive and respond in a similar manner to the signals coming from their neighbors. For example, some species of birds use directional sound signals (which require the emitter to face the receiver) to coordinate the flock movements and omnidirectional signals (with emitters moving in any direction) to attract mates or repel intruders (16). For Mormon crickets, the movement seems to be influenced by the signals received from conspecifics approaching from behind and from those positioned ahead and moving away (17). The movement direction of some fish is more frequently influenced by the movement direction of the neighbors positioned ahead of them than by those at their side (18). We focus here only on the reception of signals, because this plays a central role in the formation and movement of animal groups, by allowing the receiver to make movement decisions (19). Moreover, the reception of signals is affected by environmental conditions and the receiver's physiological limitations, and therefore different species make use of different signals and reception mechanisms (20, 21).

We take these two elements and incorporate them into a mathematical model that describes the formation and movement of animal groups. We focus on five hypothetical submodels for signal reception and use them to define the social interactions. These submodels are examples that illustrate how environmental and physiological constraints can be represented with our modeling paradigm.

The numerical simulations show the emergence of 10 types of spatial patterns. Some of these patterns are classic: stationary pulses, ripples, traveling trains, or traveling waves. However, most of the patterns have not been described previously. We call these solutions zigzag pulses, semizigzag pulses, breathers, traveling breathers, and feathers. We investigate our five submodels of signal reception in three cases [of which the first two are very common in existing models (7–9)]: (a) only attraction and repulsion, (b) only alignment, and (c) attraction, repulsion, and alignment. At the end, we focus on case (c) to investigate the conditions for full alignment within a population of individuals that is spread evenly over the domain. For this, we answer the question: how does the strength of the alignment force required in each of the five submodels depend on the amount of information an individual receives from its neighbors?

Model Description

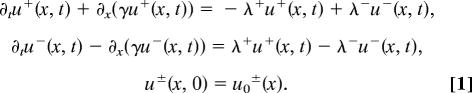

In ref. 22, the authors introduced the following model of hyperbolic partial differential equations that describes the evolution of densities of right-moving (u+) and left-moving (u−) individuals:

|

It is assumed that individuals move at a constant speed γ. The two remaining symbols, λ+ (λ−), denote the turning rates for the individuals that were initially moving to the right (left) and then turn to the left (right). These rates describe the response of an individual, through attraction, repulsion, and alignment, to the signals received from its neighbors:

We consider f to be a positive, increasing, and bounded function that depends on three nonlocal social interactions: attraction (ya±), repulsion (yr±), and alignment (yal±). Because the attraction and repulsion have opposite effects, note that they enter the equation with different signs. We will flesh out these terms shortly, when we discuss Table 1. The other two constants, λ1 and λ2, approximate the random turning rate and the bias turning rate, respectively.

Table 1.

The nonlocal terms used to describe the social interactions

| Model | Attraction and repulsion | Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | yr,a± = qr,a ∫0∞Kr,a(s)(u(x ± s) − u(x ∓ s))ds | yal± = qal ∫0∞Kal(s)(u∓(x ± s) −u±(x ∓ s))ds |

| M2 | yr,a± = qr,a ∫0∞Kr,a(s)(u(x ± s) − u(x ∓ s))ds | yal± = qal ∫0∞Kal(s)(u∓(x ± s) +u∓(x ∓ s))ds − u±(x ± s) − u±(x ∓ s))ds |

| M3 | yr,a± = qr,a ∫0∞Kr,a(s)(u(x ± s))ds | yal± = qal ∫0∞Kal(s)(u∓(x ± s) − u±(x ± s))ds |

| M4 | yr,a± = qr,a ∫0∞Kr,a(s)(u∓(x ± s))−u±(x ∓ s)ds | yal± = qal ∫0∞Kal(s)(u∓(x ± s) − u±(x ∓ s))ds |

| M5 | yr,a± = qr,a ∫0∞Kr,a(s)(u∓(x ± s)ds | yal± = qal ∫0∞Kal(s)(u∓(x ± s)ds |

The terms yr,a+ and yal+ are the translation of the diagrams from Fig. 1 into mathematical equations, when we sum up the information received from all neighbors (s ∈ (0, ∞)). The terms yr,a− and yal− are obtained through a similar process, when we consider a left-moving reference individual. We define qa, qr, and qal to be the strength of the attraction, repulsion, and alignment forces. Also, we define u to be the total density u = u+ + u−.

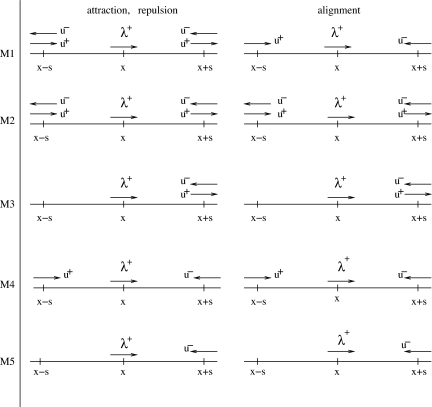

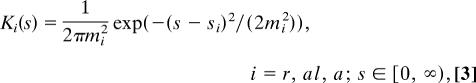

As mentioned previously, the social interactions depend on signal reception. We investigate five hypothetical submodels describing how an individual can receive signals from its neighbors. Fig. 1 shows a reference right-moving individual that is positioned at x, whereas its neighbors are potentially positioned at x + s (ahead) and at x − s (behind). The submodels are as follows: M1, the attractive and repulsive interactions depend on the stimuli received from all neighbors, whereas the alignment depends only on the stimuli received from those neighbors moving toward the reference individual (this case was studied in ref. 22); M2, all three social interactions depend on the stimuli received from all neighbors; M3, the social interactions depend only on the information received from ahead (with respect to the moving direction); M4, the social interactions depend on the stimuli received from ahead and behind, only from those neighbors moving toward the reference individual; and M5, the social interactions depend on stimuli received only from ahead and only from neighbors moving toward the reference individual. To understand Fig. 1, let us focus, for example, on M1 and, in particular, on the diagram for attraction and repulsion. We assume here that an individual is attracted (repulsed) by neighbors within the attraction (repulsion) zone, regardless of their orientation. Suppose that the reference individual receives a stronger signal from ahead than from behind, that is (u+ + u−)(x + s) > (u+ + u−)(x − s). If the signal comes from within the repulsion zone, the individual will turn to avoid those neighbors in front of it. If the signal comes from within the attraction zone, it will continue moving in the same direction. The analysis for left-moving individuals is similar (22). Table 1 describes the nonlocal terms obtained by summing up the information from all neighbors (s ∈ (0, ∞)), as depicted in the diagrams of Fig. 1. We define here the total density at (x, t) to be u(x, t) = u+(x, t) + u−(x, t). The parameters qa, qr, and qal that appear in Table 1 represent the strength of the attraction, repulsion, and alignment forces. The interaction kernels are described by the following equations:

|

with mi = si/8 (i = r, al, a) representing the width of the interaction kernels, and si (i = r, al, a) representing half the length of the interaction ranges, for the repulsion, alignment, and attraction terms, respectively. For a biologically realistic case, we consider sr < sal < sa.

Fig. 1.

Five submodels for signal reception. A reference right-moving individual is positioned at x. Its right-moving (u+) and left-moving (u−) neighbors are positioned at x + s and x − s. M1, for attraction and repulsion, the information is received from all neighbors, whereas for alignment the information is received only from those moving toward the reference individual; M2, information is received from all neighbors (for attraction, repulsion, and alignment); M3, information received only from ahead (with respect to the moving direction of the reference individual); M4, information received from ahead and behind, but only from those neighbors moving toward the reference individual; M5, information received only from ahead, and only from those neighbors moving toward the reference individual.

These five submodels are not the only possible ones. The aim here is not to describe all of the possible ways of receiving information from neighbors. Rather, it is to give the readers a flavor of the possibilities offered by such a modeling procedure. In the following, we will show that these submodels exhibit a wide variety of previously undescribed spatial patterns.

Pattern Formation

We investigate the types of spatial patterns that arise in the following three cases: (a) only attraction and repulsion; (b) only alignment; and (c) full model with attraction, alignment, and repulsion. The numerical scheme we use is a first-order upwind scheme, with periodic boundary conditions. We use this type of boundary conditions to compare our results with those obtained by other models [either continuum (8, 11) or individual-based models (23)]. Moreover, certain experimental setups also called for periodic boundary conditions (23). The infinite integrals (Table 1) are approximated by finite integrals on [0, 2si] (i = r, al, a). For the initial conditions, we focus on the spatially homogeneous steady states (u+, u−) = (u*, u**) (i.e., solutions of Eq. 1 that satisfy ∂tu± = ∂xu± = 0). We can write u** = A − u*, where A is the total population density. We choose the initial conditions for the numerical simulations to be small perturbations of these steady states.

We verified the numerical results by comparing them with analytical predictions obtained by linearizing the equations about the homogeneous solution, including a linear stability analysis, which predicts the wavenumbers of perturbations that are unstable (see also ref. 22). For predicted unstable wavenumbers, the numerical simulations show pattern formation, whereas for stable wavenumbers, there is no pattern. Moreover, the number of groups that arise depends on the wavenumber that becomes unstable: ki = 2iπ/L, i ∈ ℕ, where L is the domain length (L ≫ sa). To exclude the effect of the boundaries, we doubled the domain size, and to exclude possible artifacts of the numerical scheme, we refined the grid mesh. In all cases the results showed no significant differences.

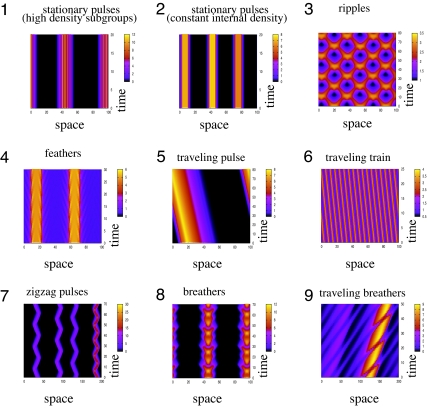

The numerical simulations reveal 10 types of spatial patterns, shown in Figs. 2 and 3: pattern 1, stationary pulses formed of small, high-density subgroups; pattern 2, stationary pulses that have a relatively constant internal density; pattern 3, ripples; pattern 4, feathers; pattern 5, traveling pulse; pattern 6, traveling train; pattern 7, zigzag pulses; pattern 8, breathers; pattern 9, traveling breathers; and pattern 10, semizigzag pulses. Patterns 1–3, 5, and 6 are classic patterns (see refs. 11 and 24). Zigzag pulses are traveling solutions that periodically change direction (22). We call feathers those stationary pulses that, at the edge, lose and gain subgroups of individuals. Breathers are stationary pulses that periodically expand and contract. Traveling breathers are breather-like groups that travel through the domain. The semizigzag pulses are pulses characterized by movement in one direction, alternated by rest. These pulses are a temporal transition between traveling trains (at the start of the simulations) and the stationary pulses (after the simulations run for a long time).

Fig. 2.

Examples of spatial patterns (shown is total density u = u+ + u−). Pattern 1, stationary pulses formed of small, high-density subgroups (shown M1: qal = 0, qa = 2, qr = 2.4, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9); pattern 2, stationary pulses (density even distributed over the group) (shown M2: qal = 0, qa = 4, qr = 0.5, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9); pattern 3, ripples (shown M5: qal = 2, qa = 1.5, qr = 1.1, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9); pattern 4, feathers (shown M3: qal = 0, qa = 6,qr = 6.4, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9); pattern 5, traveling pulse (shown M1: qal = 2, qa = 1.6, qr = 0.5, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9); pattern 6, traveling trains (shown M3: qal = 2, qa = 0, qr = 0, λ1 = 6.67, λ2 = 30.0); pattern 7, zigzag pulses (shown M2: qal = 2, qa = 6, qr = 1, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9); pattern 8, breathers (shown M4: qal = 0, qa = 2, qr = 1, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9); pattern 9, traveling breathers (shown M4: qal = 2, qa = 4, qal = 4, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9). The rest of the parameters are γ = 0.1, sr = 0.25, sal = 0.5, sa = 1.0, mr = sr/8, mal = sal/8, ma = sa/8. For these simulations, we choose the function f in Eq. 2 to be described by f(x) = 0.5 + 0.5tanh(x − 2). The initial conditions are random perturbations of amplitude 0.01 of the spatially homogeneous steady states (u*, A − u*). For patterns 1, 2, and 4–9, simulations were run for 200,000 time steps, and we plot here the last 20–80 time steps. For pattern 3, simulations were run for 10,000 time steps.

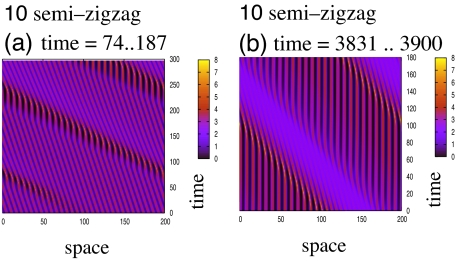

Fig. 3.

Semizigzag pattern (pattern 10). (a) Initially, all subgroups move to the left. After ≈20 time steps, some groups of individuals (shown here to be positioned in space around the mark 50) become stationary for a very short time (≈10–20 time steps). This leads to other neighboring groups, which are positioned at their left, to become stationary for a short period. This stationary behavior propagates to the left, in a wavelike manner. Moreover, the behavior is superimposed on the movement to the left displayed by these groups. (b) As time progresses, the groups remain stationary longer, and so the temporal length of this wave increases. For example, the groups positioned at the right end of the domain are stationary for ≈120 time steps. Eventually, the spatially nonhomogeneous solution will be formed only of high-density stationary groups. The parameters are as follows: qa = qr = 0, qal = 2.2, λ1 = 0.667, λ2 = 3.0, γ = 0.1, sr = 0.25, sal = 0.5, sa = 1.0, mr = sr/8, mal = sal/8, ma = sa/8. The simulations were run for 200,000 time steps (up to time t = 3,900). Here we plot some 300 time steps at the beginning of the simulations (a), and the last 180 time steps (b).

An interesting aspect of breathers and zigzag pulses is the frequency of the turning maneuver. In ref. 22, the authors have shown that in case of zigzag pulses this frequency is influenced by the magnitude of the turning rates: the smaller the turning rates, the larger the frequency. A similar result holds also for breathers. However, because of the large number of model parameters, it is possible that other parameters may also influence the turning frequency.

By fixing all of the parameters, we can investigate the role of different model assumptions (M1 vs. M2, etc.) in determining the resulting spatial pattern. We do this in the context of all three social interactions: attraction, repulsion, and alignment [i.e., case (c)]. We set qr = qa = 4, qal = 2 (that is, attraction and repulsion greater than alignment), and λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9. The rest of the parameters are given in the Fig. 2 legend. Models M1 and M2 show stationary pulses, as in Fig. 2, pattern 1. This suggests that for this particular case (i.e., qr, qa > qal), it does not matter whether the signals received from within the alignment range come only from neighbors moving toward the reference individual (M1) or from neighbors moving in both directions (M2). Model M3 shows feathers, as in Fig. 2, pattern 4. In this case, the group as a whole is stationary. However, those individuals positioned at the edge, facing away from the group, leave and do not turn around. This happens because the individuals do not receive information from behind. Model M4 shows traveling breathers, as in Fig. 2, pattern 9. This behavior is the result of two factors. First, because repulsion has the same magnitude as attraction, individuals can escape the group. These individuals move faster than the rest of the group. The rest of the group executes a sort of zigzag (those very-high-density patches displayed by pattern 9). Second, the boundary conditions are periodic. That is, individuals that have left the group now are joining it again. This leads to expanding and contracting moving groups (i.e., traveling breathers). Model M5 shows ripples, as in Fig. 2, pattern 3. In this case, the individuals react only to signals coming from ahead. This way, when two left-moving and right-moving waves approach each other, the majority of individuals within each group turn around, to avoid collision. However, there are some individuals that continue moving in the same direction. This behavior leads to the appearance that the waves pass through one another.

Table 2 shows a summary of the patterns observed in the three cases: (a) only attraction and repulsion, (b) only alignment, and (c) attraction, repulsion, and alignment. The dashes denote that the pattern was not observed. Because we do not sample the entire parameter space, we note that Table 2 might not be complete. Moreover, we believe it is likely to find other new and interesting patterns in different parameter subspaces. Our aim here is not to find all patterns, but to open the door toward the numerous possibilities offered by our modeling procedure.

Table 2.

A summary of the different types of possible solutions exhibited by the five models, M1–M5

| Model | Travel. train | Travel. pulse | Stat. pulse | Zigzag pulse | Semi-zigzag pulse | Breather | Travel. breather | Feather | Ripples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | (b) | (c) | (a),(b),(c) | — | (b) | — | — | — | — |

| M2 | (b),(c) | (b),(c) | (a),(c) | (c) | — | — | — | — | — |

| M3 | (b) | (c) | — | — | — | — | — | (a),(c) | — |

| M4 | (b) | (c) | (a),(b),(c) | (a),(c) | (b) | (a) | (a),(c) | — | — |

| M5 | — | — | (b) | — | — | — | — | — | (a),(c) |

Here (a), (b), and (c) represent the three discussed cases: (a) only attraction and repulsion, (b) only alignment, (c) attraction, repulsion, and alignment. The dashes mean that the pattern has not been observed. We focused on the parameter space where the wavenumbers of the perturbations are unstable, as predicted by the linear stability analysis. However, since this parameter space is very large, we have sampled only some parameter subspaces. Case (a): fix qal = 0, γ = 0.1, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9, and A = 2. The sampled parameter subspace is (qa, qr), with qa, qr ∈ [0.5, 9]. For the initial conditions we consider u* = u**. Case (b): fix qa = qr = 0, γ = 0.1, A = 2, and investigate the influence of the turning rates on the group structure. For this, we define λ1 = 0.2/τ, λ2 = 0.9/τ, and vary τ. The sampled parameter subspace is (qal, τ), with qal ∈ [0.5, 10], and τ ∈ [0.006, 1]. For the initial conditions we take u* ≠ u**. Case (c): fix γ = 0.1, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9, A = 2. The sampled parameter subspace is (qa, qr), with qa, qr ∈ [0.5, 10]. For the initial conditions we consider u* = u**. The obtained patterns are robust to parameter changes, in the sense that each pattern is observed for a range of parameters.

Relation Between Information Received and Alignment

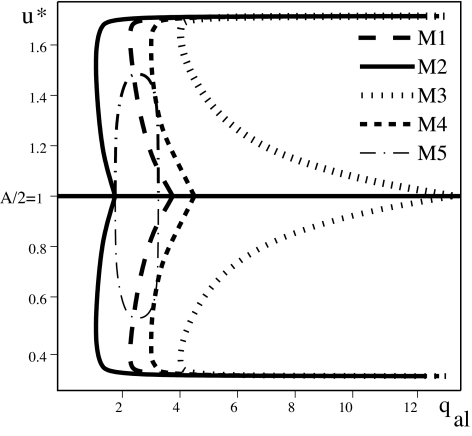

In addition to the discussed patterns, we investigate conditions under which a population of individuals evenly spread over the domain has most of its members aligned in the same direction. That is, we look for spatially homogeneous steady states of the form (u*, A − u*), with u* ≠ A/2. For this, we focus on the relation between the strength of the alignment force required in each of the five submodels M1–M5 and the amount of information an individual receives about its neighbors. Fig. 4 shows the relationship between the strength of this force (qal) and the spatially homogeneous steady states that arise in each of the submodels. Depending on how much information it receives about its neighbors, an individual requires different levels of alignment. For example, we see that for M2, small qal already leads to polarization. In this case, the individuals receive all possible information about neighbors positioned ahead and behind them (see Fig. 1). For M3, on the other hand, only a large qal value leads to polarization. In this case, the individuals receive information only from ahead. By comparing M3 and M4, we see that group polarization occurs for smaller values of alignment (qal) when receiving partial information from both ahead and behind (M4), as compared with receiving full information only from ahead (M3). However, receiving information only from ahead, and only from neighbors moving in one direction (M5), leads to a lower level of polarization. Moreover, this polarization happens only for some intermediate values of qal.

Fig. 4.

Bifurcation diagram comparing the spatially homogeneous steady states (u*, A − u*) displayed by the five models M1–M5 as alignment increases (total density A = 2, qa = 1.5, qr = 1.1, λ1 = 0.2, λ2 = 0.9). We see that for M2, a small qal value already leads to polarization [i.e., the steady state is (u*, A − u*), with u* ≠ A/2]. M3, on the other hand, requires a larger value for qal. For M5, only intermediate values of qal lead to some polarization.

We conclude that there is an inverse relation between the amount of information received and the strength of alignment force required to fully align with neighbors. A similar result (not shown here) holds also for the turning rates.

Discussion

In this paper, we have presented a one-dimensional mathematical model for animal group formation that exhibits 10 complex patterns. A one-dimensional continuum model for group formation exhibiting such a variety of emergent patterns has not been reported previously. We should note that the described patterns hold scientific interest. To our knowledge, some of these patterns (e.g., feathers) have never been previously observed. The results also show that the way organisms receive information may play a central role in the emergence of complex patterns observed in biological aggregations. Some of the patterns can be connected to observed group behaviors: zigzagging flocks (25, 26), rippling behavior shown by populations of Myxobacteria (11), traveling pulses and stationary pulses corresponding to moving (e.g., traveling schools of fish) and resting groups of animals, and traveling trains corresponding to waves of activity that propagate through the groups (27). Breathers might be associated with the antipredatory behavior observed in some schools of fish (28) or flocks of birds (29), when the groups expand and then contract.

Because of the complexity of the animal aggregations, it has been difficult to quantify the different types of groups and animal movements. One step forward was made in ref. 23, where the results of an individual based model were compared with laboratory experiments. The results we present here invite further observations and experimental investigations involving the manipulation of communication in animal groups.

In the formulation of the model, we have restricted ourselves to one spatial dimension. In nature, the majority of biological aggregations are in two or three dimensions. However, the simulations show that this model captures the essential features of some of the observed patterns [e.g., higher population density at the front of the moving groups (30) and the structure of the turning maneuver (31, 32)]. The one-dimensional model can approximate the behavior of animal groups in two dimensions if they move in a domain that is much longer than wide. However, for a more realistic and general case, the model should be extended to two spatial dimensions (see, for example, ref. 33).

Some of the patterns we obtained in this paper can be related to the patterns displayed by the other continuum models existent in the literature. In particular, the results in Table 2 show that case (a) (i.e., only attraction and repulsion) almost always generates stationary pulses. This pattern was previously obtained by parabolic models with attractive and repulsive interactions (7). The traveling pulses seem to be the result of the interplay between all social interactions [case (c)]. Compared with previous models (8), the pulses obtained here have well defined boundaries and persist for a very long time. The ripples (similar to the ones described in refs. 9 and 11) are obtained here for cases (a) and (c). We therefore conclude that our model not only exhibits the patterns obtained by other one-dimensional continuum models (i.e., stationary pulses, traveling pulses, and ripples), but also shows new types of solutions.

Furthermore, the results suggest that there is an inverse relation between the amount of information received by an organism (due to environmental or physiological limitations) and the strength of the alignment that leads to a polarized population.

Future areas of research include investigating whether observed patterns change if we change the nonlinear turning function (Eq. 2) or the interaction kernels. For example, we observed that in model M1 all but the semizigzag pulse patterns persisted when we used odd kernels for attractive and repulsive interactions (22).

We stress that this model approach provides a structure for further modifications. The mathematical model can easily be adapted to a particular species by changing the way we model how organisms receive information from their neighbors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frithjof Lutscher for helpful discussions related to the model derivation. R.E. was supported by a University of Alberta F. S. Chia Scholarship and a Josephine Mitchell Graduate Scholarship. G.d.V. was supported in part by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Discovery Grant. M.A.L. was supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant and Canada Research Chair.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Parish JK, Edelstein-Keshet L. Science. 1999;284:99–101. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couzin ID, Krause J, James R, Ruxton GD, Franks N. J Theor Biol. 2002;218:1–11. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2002.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huth A, Wissel C. Ecol Model. 1994;75/76:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Painter KJ, Maini PK, Othmer HG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5549–5554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo S, Asai R. Nature. 2002;376:765–768. doi: 10.1038/376765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edelstein-Keshet L, Watmough J, Grünbaum D. J Math Biol. 1998;36:515–549. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topaz CM, Bertozzi AL, Lewis MA. Bull Math Biol. 2006;8:1601–1623. doi: 10.1007/s11538-006-9088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mogilner A, Edelstein-Keshet L. J Math Biol. 1999;38:534–570. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutscher F, Stevens A. J Nonlinear Sci. 2002;12:619–640. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfistner B. J Biol Systems. 1995;3:579–588. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Igoshin OA, Welch R, Kaiser D, Oster G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4256–4261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400704101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topaz CM, Bertozzi AL. SIAM J Appl Math. 2004;65:152–174. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mogilner A, Edelstein-Keshet L. Physica D. 1996;89:346–367. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bressloff PC. SIAM J Appl Math. 2004;64:1668–1690. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds CW. Computer Graphics. 1987;21:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witkin SR. The Condor. 1977;79:490–493. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson SJ, Sword GA, Lorch PD, Couzin ID. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4152–4156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508915103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Olst JC, Hunter JR. J Fish Res. 1970;27:1125–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marler P. Science. 1967;157:769–774. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3790.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endler JA. Am Nat. 1992;139:S125–S153. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endler JA. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1993;340:215–225. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1993.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eftimie R, de Vries G, Lewis MA, Lutscher F. Bull Math Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s11538-006-9175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buhl J, Sumpter DJT, Couzin ID, Hale JJ, Despland E, Miller ER, Simpson SJ. Science. 2006;312:1402–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.1125142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray JD. Mathematical Biology. New York: Springer; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphries DA, Driver PM. Oecologia. 1970;5:285–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00815496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis M. Anim Behav. 1980;28:668–673. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uvarov B. Grasshoppers and Locusts. London: Centre for Overseas Pest Research; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freon P, Gerlotto F, Soria F. Fish Res. 1992;15:45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Major PF, Dill LM. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1978;4:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bumann D, Krause J. Behaviour. 1993;125:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Partridge BL, Pitcher T, Cullen JM, Wilson J. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1980;6:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pomeroy H, Heppner F. The Auk. 1992;109:256–267. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfistner B, Alt W. Biol Motion Lect Notes Biomath. 1989;89:564–565. [Google Scholar]