Abstract

The dendritic-nucleation/array-treadmilling model provides a conceptual framework for the generation of the actin network driving motile cells. We have incorporated it into a 2D, stochastic computer model to study lamellipodia via the self-organization of filament orientation patterns. Essential dendritic-nucleation submodels were incorporated, including discretized actin monomer diffusion, Monte-Carlo filament kinetics, and flexible filament and plasma membrane mechanics. Model parameters were estimated from the literature and simulation, providing values for the extent of the leading edge-branching/capping-protective zone (5.4 nm) and the autocatalytic branch rate (0.43/sec). For a given set of parameters, the system evolved to a steady-state filament count and velocity, at which total branching and capping rates were equal only for specific orientations; net capping eliminated others. The standard parameter set evoked a sharp preference for the ±35 degree filaments seen in lamellipodial electron micrographs, requiring ≈12 generations of successive branching to adapt to a 15 degree change in protrusion direction. This pattern was robust with respect to membrane surface and bending energies and to actin concentrations but required protection from capping at the leading edge and branching angles >60 degrees. A +70/0/−70 degree pattern was formed with flexible filaments ≈100 nm or longer and with velocities <≈20% of free polymerization rates.

Keywords: lamellipodium, cytoskeleton, plasma membrane

The polymerization of soluble actin monomers between filament “barbed ends” and the plasma membrane (PM) generates the force of protrusion in cell motility (1, 2). Other proteins required for lamellipodial motility (3) are arp2/3, which nucleates (branches) free barbed ends at ≈70 degrees from existing ones (4); a PM-bound activator of arp2/3 (5); ADF/cofilin, which promotes the depolymerization of pointed ends (6) and perhaps debranching reactions (7); and capping protein, a terminator of barbed end growth (8). The generation and persistence of lamellipodia from these elements is described in the “dendritic-nucleation/array-treadmilling” conceptual model (2, 4, 9). This model can be subdivided into three main processes: the kinetics of filament (de)polymerization, branching, and capping; filament–PM interactions, which limit polymerization rates; and the diffusion of actin monomers and other soluble components. Such a system is “complex” in the sense that many copies of each component type interact to exhibit “emergent” system properties not expected from the individual rules of interaction (10). In contrast to “complicated” systems of many dissimilar components with precisely defined interactions, complex systems can self-organize and adapt to environmental change.

An important emergent property is the self-organization of lamellipodial actin filaments into orientations at ±35 degrees with respect to the direction of protrusion (11, 12). Maly and Borisy (11) predicted ±35 or +70/0/−70 degree patterns with a 2D mathematical model based on these dendritic-nucleation assumptions. A model by Atilgan et al. (13) allowed 3D branching, but required preferential arp2/3 orientation in the PM for pattern formation. The numerical model described here extends the Maly and Borisy (11) model, removing most of its simplifications and limitations. Reactions are treated stochastically, the elastic properties of the membrane and filaments are included, and the time-dependence of the distribution's evolution is obtained. We preserve the assumption that filaments remain oriented in the 2D lamellipodial plane. Our simulation exhibits orientational self-organization and permits the determination of a range of parameter values consistent with pattern stability. We reveal the transient development of the orientation pattern and the approach to steady-state protrusion velocity and filament number.

Several computer models of (rigid) bacterial propulsion by rigid filaments have been proposed (14–16), with those of Carlsson demonstrating a flat force–velocity relationship under autocatalytic branching (15, 16). Mogilner and Oster (17, 18) developed the basic theory of the actin-based elastic Brownian ratchet, which applies small-angle elastic beam theory to thermal filament fluctuations. The present model combines stochastic propulsion and elastic filament models, adding a flexible PM load and thermodynamically realistic filament–membrane interactions.

Assumptions and Methods

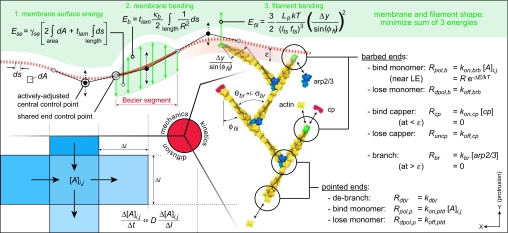

An ≈1 μm-wide (X) portion of a flexible lamellipodial leading edge (LE) was simulated, with cyclic boundary conditions for all components on the ≈1 μm Y axis edges and a fixed actin monomer concentration [A]TE on the trailing edge. Every filament over the entire lamellipodial thickness was modeled, with 2D positions, orientations, and end states of each filament recorded individually. Over each small time step Δt, the calculation algorithm performed spatially discretized (Fick's law) diffusion and Monte-Carlo (stochastic) kinetics calculations for all components, with iterative calculations of PM and filament mechanics as required (Fig. 1 and Tables 1 and 2). Consistent with experimental indications that branching and anticapping mechanisms operate very near the LE, free barbed ends within a Y-distance ε branched new filaments at rate Rbr and were blocked from the usual capping rate Rcp. New filaments deviated from the parent filament barbed end orientation by a normal distribution about the mean branch angle ±(θbr±σbr). Polymerization occurred at a rate proportional to the local actin monomer concentration, reduced at the LE by a Boltzmann factor based on the total system energy required for that specific protrusive step. Filaments were assumed to be either rigid or flexible and cantilevered from the nearest branch or pointed end. Values for the filament and PM mechanical properties and most of the reaction rate constants were available. The main unknowns were the effective rates of branching and capping, critical to the development of the filament distribution. With Rcp available, ε and Rbr were determined from simulation (see Fig. 3), completing the standard set of parameters listed in Table 2. Model details and a simulation video depicting individual protrusive steps can be found in supporting information (SI) Methods and Movie 1.

Fig. 1.

Lamellipodia were simulated using three submodels. (Lower Left) A fixed rectangular grid demarcated regions of uniform actin concentration, subject to Fick's diffusion relation between them. (Right) Within each time step, kinetic reactions were carried out stochastically for every filament. (Upper) Minimization of PM and filament potential energies yielded quasi-SS geometries between kinetic states.

Table 1.

Symbols

| R | Radius of curvature of the LE in the plane of simulation |

| VPM; Vfree | Velocity of the LE center of mass; free polymerization velocity |

| ΔE | Thermal energy required for intercalating a monomer between LE and barbed end = Δ(ΣEb + ΣEse + ΣEfil) over successive potential states |

| EbEse Efil | PM bending, PM surface, and filament bending potential energies |

| ds; dA | Differential length along LE; differential area of plasma membrane |

| lts | Filament terminal segment length, from barbed end to first branch |

| φfil | Filament orientation angle, with respect to the direction of protrusion |

| αd | Mean absolute filament deviation angle, measured from population mean |

| [A]; [A]i,j | ATP-G-actin concentration, in general; local conc. at position (i,j) |

| fε | Average fraction of all free barbed ends within the ε-demarcated LE zone |

| t1/2 N1/2 | Half-time; number of branching generations to develop orientation pattern |

Table 2.

Model parameters and standard values

| Symbol | Value | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| δ | 2.7 nm | Extension length of polymerizing actin monomer | — |

| D | 6.0 μm2/sec | Cytoplasmic actin monomer diffusion coefficient | 19 |

| [A]TE | 12 μM | Fixed, trailing edge actin monomer concentration | 20 |

| γse | 50 pJ/nm2 | Plasma membrane surface energy coefficient | 18, 21 |

| κb | 80 pN nm | Bending energy coefficient, ≈20 kT | 21 |

| Lp | 10 μm | Persistence length of actin filaments | 22 |

| tlam | 200 nm | Lamellipodial thickness | 20 |

| kon,brb | 12 /μM/sec | On-rate of actin to barbed end ≡ Rpol,b/[A] | 23 |

| koff,brb | 1.4 /sec | Off-rate of actin from barbed end ≡ Rdpol,b | 23 |

| kon,ptd | 0/μM/sec | On-rate of actin to ptd. end, profilin-adj. ≡ Rpol,p/[A] | 24 |

| koff,ptd | 8.0/sec | Off-rate of actin from ptd. end, cofilin-adj. ≡ Rdpol,p | 6 |

| ε | 2.0 δ | LE cap-protection/branch zone (Y) length | 15 |

| Rbr | 0.43/sec | (Total) rate of barbed end branching ≡ kbr [arp2/3] | 18, 20 |

| Rdbr | 0.05/sec | Rate of debranching for any branch point | 25 |

| Rcp | 6.0/sec | Rate of barbed end capping ≡ kon,cp [cp] | 26 |

| Runcp | 0/sec | Uncapping rate for any capped barbed end ≡ koff,cp | 26, 27 |

| Nfb | 200 fil/μm | Free barbed ends per LE width (indirectly spec.) | 20 |

| θbr | 70 deg. | Average branch angle | 4 |

| σbr | 7 deg. | Branch angle SD | 4 |

| Dt | 0.0004 sec | Simulation time step | — |

| fts | 0 (≡ rigid) | Fraction of terminal segment length in fil bending | Text |

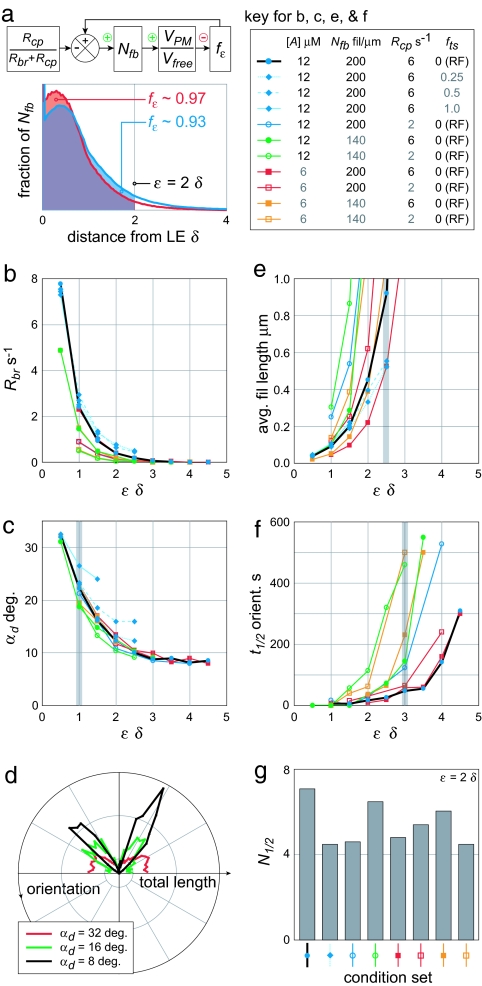

Fig. 3.

Orientation pattern and filament length were examined for several parameter sets to determine standard branching parameter values. (a) The distribution of Y-distances from free barbed ends to the LE is shown for standard conditions (Rbr = 0.43/sec, fε = 0.93, and VPM/Vfree = 0.36, blue) and a reduced Nfb of 140 fil per μm (Rbr = 0.21/sec, fε = 0.97, and VPM/Vfree = 0.28, red). Distances in units of δ. (b) For all conditions, the Rbr required to sustain the specified Nfb increased sharply at low ε. (c) The extent of filament deviation from the average orientation (αd) increased from near σbr to >30 degrees at ε = 0.5 δ under all conditions. (d) Orientation patterns for three αd values plotted, with backward-facing filaments rotated by 180 degrees to make them comparable to EM data, suggested a lower limit of ε ≈1.0 δ. (e) High ε resulted in unreasonably long filament lengths, restricting ε to < 2.5 δ. (f) The half-time to develop an SS pattern (t1/2) from an initial 15-degree asymmetry also increased with ε, supporting ε < 3 δ. (g) The characteristic number of branching generations required to approach SS (N1/2) was similar for all parameter sets at a given ε (2.0 δ shown).

Results and Discussion

Self-Organization of Filament Orientation Arose Under Any Initial Conditions (ICs).

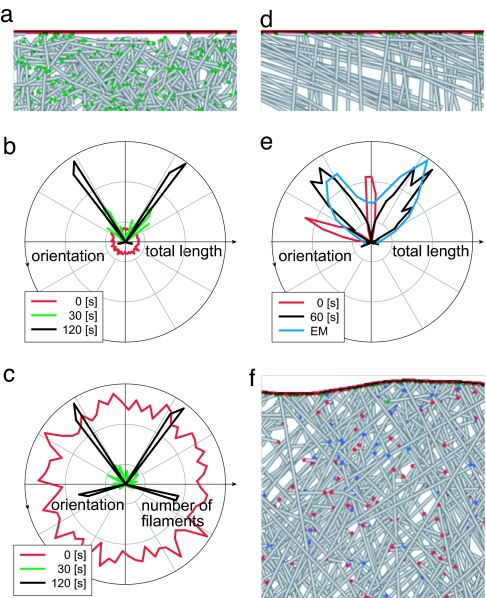

We first asked under what ICs the model system would organize filament orientation. A set of filaments at random position, orientation, and length has no order, with only the position of the branch-inducing and capping-protective LE to generate directionality. A simulation was run under these ICs (Fig. 2a), with the branch angle SD (σbr) equal to zero and otherwise standard parameter conditions (Table 2). Results show the disappearance over 120 sec of total filament length (mass) in most orientations, with one pair of very sharp orientations at ±35 degrees dominating (Fig. 2 b and SI Movie 2). Because the branch angle did not vary, filament populations always occurred in strictly complementary families (related by exactly 70 degrees) and were not able to drift into other orientation families over successive generations of branching. This result shows that from ICs without order, very narrow populations of filaments oriented at 35 degrees show net growth, whereas others show net depolymerization.

Fig. 2.

Filaments in the model spontaneously self-organized from any ICs into preferential orientations ±35 degrees from the leading edge (LE) perpendicular. (a) ICs of simulations in b and c, showing random filament barbed-end position, orientation (0–360 degrees), and length (0–150 nm) over 0.5 × 0.35 μm of a 1 × 1 μm simulation. Fifty percent of filaments shown; standard parameter set of Table 2, except σbr = 0 degrees; free barbed ends labeled green. (b) Polar histogram plots of total filament length versus orientation displayed a sharp preference for ±35 degree orientations, with loss of others. (c) Plotted by number of filaments, a similar pattern was observed, but with backward-facing filaments made obvious. (d) ICs of standard parameter simulations (σbr = 7 degrees) in e and f, showing orientations near −70/0 degrees. (e) Polar plots of total length over time show adaptive behavior and compare favorably with EM measurements at SS. (f) Image of a 0.5 × 0.5 μm section at SS. Capped barbed ends labeled red, blue dots denote branches. At SS, the 1 × 1 μm simulation contained 700 filaments totaling 250 μm in length, with 200 free barbed ends.

When the number of filaments, instead of the total filament length, in each direction is plotted, we see a similar pattern with the addition of backward-facing filaments at ±105 degrees (Fig. 2c). Other orientations showed a net decrease in the number of filaments, showing that the total capping rate outpaced the total generation rate for those orientations until their numbers reached zero. Domination by length at ±35 degrees thus did not represent a system in which ±35 degree filaments became particularly long, but instead one in which other filament families were not viable. Filaments that faced backward at ±105 degrees were generated at nearly the same rate as forward-facing filaments, but rapid capping away from the LE kept their total lengths (and nonproductive monomer depletion) very low (Fig. 2b), and subsequent debranching and depolymerization reduced their count moderately (Fig. 2c).

It remained to be shown that the model could adapt from initial orientation patterns devoid of 35 degree filaments into the steady-state (SS) ±35 degree patterns. This is necessary because a feature of motile cells is their ability to reorganize filament orientations in response to changes in the direction of protrusion, without which we would not observe the ±35 degree pattern in cells that turn. Initial conditions of filaments oriented near −70/0 degrees simulated a sudden, 35 degree clockwise turn in protrusive direction from a previous SS pattern (Fig. 2d). The standard σbr of 7 degrees was used allowing the population to drift into new orientations, but no 35 degree filaments existed initially. Orientations became symmetrical within 1 min, with a broader distribution of orientations centered on ±35 degrees (Fig. 2e). The SS distribution compared favorably to those measured via digital image-processing techniques (Radon transform) from lamellipodial electron micrographs (EMs) (11) (Fig. 2e, with an image at SS shown in Fig. 2f). We conclude that ICs of all protrusive simulations with standard parameter values evolve and adapt into ±35 degree patterns consistent with EMs.

Simulation Indicated Plausible Branching Parameters.

The standard parameter set used in Fig. 2 and the rest of this study came from both the literature and simulation. Although experimental data provided relatively direct estimates for Nfb, Rcp, and [A] values, Rbr and ε were more difficult to estimate. Modeling allowed us to determine Rbr, ε, and the filament bending length parameter fts, consistent both with estimates for Nfb, Rcp, and [A] and with experimentally accessible values such as orientation pattern and filament length.

A particular Nfb is set only indirectly, through filament turnover parameters Rbr, Rcp, and ε. For a given VPM/Vfree, the profile of Nfb with distance from the LE is similar (Fig. 3a, the exact shape of which will be considered in a subsequent publication). At SS, a fraction of these free barbed ends, fε, are within the ε-demarcated region, and the total rates of filament branching and capping are balanced: (Nfb fε) Rbr = (Nfb [1-fε]) Rcp. The SS fε therefore equals Rcp/(Rbr+Rcp), the setpoint for a negative-feedback loop controlling Nfb and VPM/Vfree: A low VPM relative to Vfree allows filaments to keep up with the LE more often, raising fε above the setpoint. The resulting net branching increases VPM/Vfree. Conversely, a high VPM/Vfree results in net capping and a decrease in Nfb and VPM/Vfree.

Plots were made of the Rbr values required to sustain a steady Nfb at a given ε, with two values each of Nfb, Rcp, fts, and [A] specified and the diffusion coefficient (D) set very high to maintain [A] uniformly (Fig. 3b). The value of [A] was not a factor in the required Rbr; it affected both VPM and Vfree (= kon,brb [A] δ) equally, and curves are superimposed. (Comparison is therefore by VPM/Vfree throughout this study.) In contrast, maintaining higher Nfb values required a higher Rbr because the associated increase in VPM/Vfree diminished fε. A decrease in Rcp was associated with an approximately proportional decrease in required Rbr, as expected. Filament flexibility was allowed in three parameter sets, and moderately raised the required Rbr. The most sensitive parameter was ε itself. Decreasing ε dramatically decreased fε, requiring a compensatory increase in Rbr.

To narrow the range of acceptable values of ε and Rbr, the quality of the SS orientation distribution was assessed. Quality was quantified as the mean absolute deviation (αd) from the mean orientation angle. The αd values for all parameter sets were very similar at the same ε (and Rbr) values, with some increase in αd with filament flexibility (Fig. 3c). Polar histograms of orientation distributions over a range of αd showed focused distributions at high ε and noisy and distorted distributions, incompatible with EM data, at very low ε (Fig. 2d). These results are compatible with ε values as low as 1 monomer length (δ = 2.7 nm), but not less.

To limit the upper values of ε, we analyzed average filament lengths and orientation pattern development times. Again, because large ε values were associated with low Rbr, filaments turned over slowly and thus grew very long before being capped. Using EMs, conservative visual estimates of the average length of filaments within 1 μm of the LE ranged from 50 to 500 nm (data not shown). In simulations, the number of filaments was a decaying function of length, with all parameter sets consistent with a maximum 500 nm average length when ε was held to <2.5 δ (Fig. 3e). Supporting this limit were measurements of the half-time of orientation pattern development (t1/2) from a 15 degree simulated turn (i.e., ICs of a distribution centered on +20 and −50 degrees), with full recovery defined as a SS αd value. At ε = 3.0 δ, all parameter sets yielded a t1/2 of 60 sec or more (Fig. 3f), corresponding to ≈3 min recovery times for a minor 15 degree turn. In comparison, fibroblasts have lamellipodial protrusion persistence times on the order of 1–2 min before retraction (28). Length and recovery time considerations were thus limited by two criteria to ε < 2.5 δ.

Of related importance to t1/2 is the number of branching generations required for network self-organization. The product of t1/2 and Rbr yields the number of generations required for a 50% recovery in αd after a rapid, 15 degree turn (Fig. 2g). Regardless of parameter conditions, this N1/2 value was consistently ≈5 generations for ε = 2.0 δ. Three half-times (87.5% recovery) required 15 generations. For ε = 3.0 δ, three half-times still required ≈9 generations. These generations must be largely successive (i.e., parents branching children, then children branching grandchildren) for adaptation to occur.

Based on these studies, we chose a standard set of parameter values consisting of ε = 2.0 δ, Rcp = 6.0 /sec, and [A] = 12 μM, with which reasonable protrusion rates of 8 μm/min were achieved. Furthermore, an Nfb of 200 fil per μm was compatible with measurements of filament barbed end count (20) and length, and required an Rbr of 0.43/sec. Filaments were held rigid (fts = 0) for simplicity except where noted.

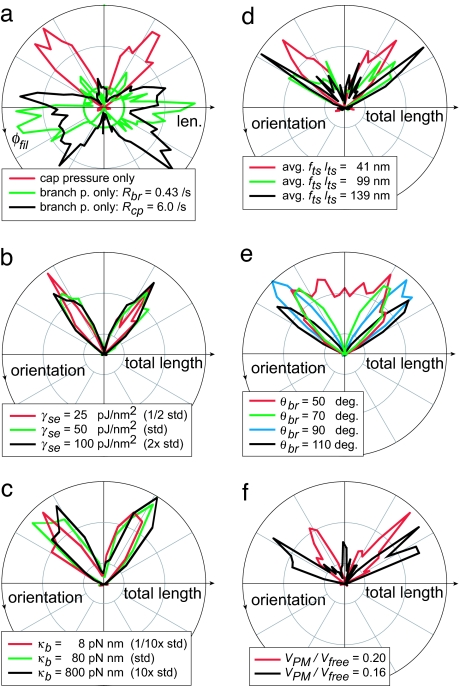

The SS Orientation Pattern Is Sensitive to Several Model Parameters.

In the standard model, the same ε value limited capping protection and branching initiation. When branching was allowed at any free barbed end, regardless of position, but capping protection was maintained within ε, orientation distributions remained unchanged (Fig. 4a). These conditions were effectively similar to standard conditions because the high intrinsic capping rate quickly removed free barbed ends arising beyond ε. (Although we did not simulate branching from the sides of filaments away from their barbed ends, we predict a similar result.) In contrast, when branching was only allowed within ε and capping was allowed anywhere, the orientation pattern changed dramatically. Cases in which Nfb and Rbr were maintained at standard values required a greatly diminished Rcp of 0.22 per sec, whereas those with standard Nfb and Rcp required a greatly elevated Rbr of 12 per sec. Both cases resulted in distributions with most filament mass facing backward, incompatible with EM results. Protection from capping near the LE is thus essential for the formation of the ±35 degree distribution.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity of patterns to nonbranching parameters further suggested limits to in vivo values. Polar plots include all filaments in an LE 1 × 1 μm area. (a) Deviating from standard conditions, maintaining branching pressure but allowing capping anywhere resulted in a nonphysiological, high backward-filament mass. (b) Altering surface energy (γse) values alone did not affect orientation pattern. (c) Varying PM bending energy (κB) altered the variability in LE shape but did not alter the pattern. (d) Simulations with varying filament flexibility all had average terminal segment lengths (lts) of ≈200 nm. When effective bending lengths exceeded ≈41 nm, orientation patterns similar to +70/0/−70 degree distributions resulted. (e) Setting the mean branching angle (θbr) near or below 60 degrees resulted in a broad distribution. (f) Velocities of at least ≈20% of Vfree were required for ±35 degree orientation patterns.

Membrane model parameters were not found to significantly affect orientation distributions over a wide range of values. Given a constant Rbr, runs varying the resistance to protrusion (γse) retained the same VPM and ±35 degree distribution due to the compensating effect of Nfb (Figs. 3a and 4b). This flat force–VPM relationship is a characteristic of unrestrained autocatalytic branching, observed by Carlsson (16). Membrane flexibility, specified by the bending energy coefficient, κb, had a significant effect on the LE shape over length scales of <200 nm. Although the pattern is formed with respect to the LE perpendicular, this had no effect on the orientation distribution, with the same pattern attained over two orders of magnitude of κb variation (Fig. 4c). We attribute this stability to the LE's horizontal average orientation and rapid fluctuations relative to filament lifetime.

Conversely, filament bending stiffness had a large influence on the orientation pattern. This stiffness is dependent on the third power of effective filament bending length [(fts lts)3, with the fraction fts simulating cross-linking]. Standard parameter simulations with effective filament lengths averaging 0 (fts = 0, equivalent to rigid) or 41 nm (fts = 0.25) yielded ±35 degree distributions, but 99 or 139 nm lengths (fts = 0.50 or 0.75, respectively) resulted in distributions similar to +70/0/−70 degree triplets (Fig. 4d). These length limits are consistent with Mogilner and Oster's (17) force generation calculations. Triplets were a result of barbed-end “splaying” to higher angles under load.

The branch angle (θbr) itself was not important to the final ±θbr/2 distribution over values of 70–110 degrees, but smaller θbr values resulted in a single uniform mass (Fig. 4e). Allowing splaying by filament flexibility did not revive the two-peak distribution (data not shown). Note that filaments branching from θbr/2 no longer face backward at θbr = 60 degrees, but rather 30 + 60 = 90 degrees. This allows them an increased opportunity to further branch and disperse the population orientation. Among θbr values that form two-peak distributions, the t1/2 from ICs (uniformly distributed over the range of ±90 degrees) is also sharply minimized at θbr = 70 to 80 degrees (data not shown). A 70 degree branch angle is therefore optimized for rapid generation of a stable two-peak orientation pattern.

Changes in Vfree had no effect on the orientation pattern (data not shown), but the ratio VPM/Vfree was important. Holding Vfree constant, the SS VPM was diminished by decreasing Rbr (this raises the SS fε requirement; see Fig. 3a). An Rbr of 0.06/sec yielded VPM/Vfree = 0.20 and a ±35 degree distribution (Fig. 4f). Decreasing Rbr to 0.03/sec lowered the SS VPM/Vfree to 0.16 and produced an SS triplet distribution, but also lowered Nfb to 80 fil per μm. Raising γse to restore Nfb had no effect on the distribution or VPM/Vfree (plotted). Note that low Rbr can lead to long filament lengths and slow self-organization (Fig. 3), and triplet patterns in vivo would be more suggestive of a small ε value (which instead lowers VPM to reach the same required fε). Note also that, on average, a 70 degree filament advances at Vfree cos (70) = 0.34 Vfree, but that stochastically growing filaments bounded ahead by the PM do not maintain a high fε at this velocity and in fact require VPM/Vfree < 0.20 to dominate under standard values.

The Evolution of the Final Orientation Pattern and the Development of the SS VPM Were Interdependent.

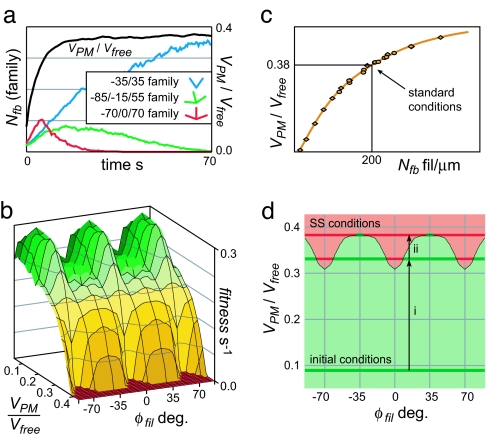

From ICs of a small number of filaments at random orientation, Fig. 5a tracks the total number of filaments in each of three complementary-orientation “families” over time. At the low Nfb and VPM values early in the simulation, the +70/0/−70 degree triplet multiplied at the highest rate. With increasing VPM, however, the number of filaments decreased in turn for each family until only the ±35 degree pair remained at SS VPM.

Fig. 5.

The orientations of maximum fitness vary with VPM/Vfree, but the SS pattern is that with zero fitness at the equilibrium VPM. (a) The sum of +70/0/−70 degree filaments grew fastest in number at low Nfb and VPM, but only the ±35 degree population remained at SS VPM (standard conditions with σbr = 0 degree and a rigid PM for clarity). (b) The 3D fitness landscape for standard conditions. (c) VPM/Vfree rises with Nfb. (d) A 2D representation of b shows positive (green) or negative (red) fitness at a given velocity and orientation. At low VPM/Vfree, all orientations undergo net reproduction, raising Nfb and VPM/Vfree. The “terminal” VPM is achieved by, and limited to, the ±35 degree family.

Following Maly and Borisy's evolutionary “fitness” concept, fitness = (rate of change of Nfb)/(Nfb) for each orientation. The value is positive if a population is growing in number, zero if constant, and negative if decreasing toward extinction. Fig. 5b shows the fitness landscape for standard branching parameters as a function of φfil and VPM/Vfree, with the two symmetric patterns, +70/0/−70 and ±35 degrees, having maximum fitness at low and high velocities, respectively. When either pattern is rotated slightly, the capping rate of the filament with the largest φfil increases faster than the branching rate of its parent, causing a net decrease in fitness. Because ≈2/3 of new filaments branching from the triplet contribute to the pattern (1/2 each of branches from ±70 degree filaments, and 2/2 branches from 0 degree filaments ≈4 of 6 new filaments), whereas only 1/2 of branches from ±35 degree filaments contribute to their pattern, the triplet has a superior reproductive rate and fitness at low velocities. At higher protrusion rates, this effect is overcome by the low fε of slow 70 degree filaments.

To identify the SS condition from Fig. 5b, we note that, under any model context, an increase in SS Nfb always increases SS VPM/Vfree due to the higher net rate of protrusive kinetic events (Fig. 5c). A typical path through the fitness landscape can therefore be shown as a Darwinian evolution of patterns through the flattened landscape representation in Fig. 5d. At low Nfb, all forward-facing orientations interact with the same low-velocity PM and exhibit net branching [fε Rbr > (1-fε) Rcp for every φfil]. This leads to an increase in Nfb and VPM and to an environment in which filaments at orientations near 0 and ±70 degrees decrease in count (Fig. 5d, i). Because any VPM with orientations of positive fitness will ultimately result in an increased total Nfb, this cycle will continue (Fig. 5d, ii) until reaching the equilibrium VPM and its only viable orientations, near ±35 degrees. There, fε Rbr = [1-fε] Rcp for 35 degree filaments (i.e., fitness = 0), but all other orientations are driven to extinction by net capping. Given different branching parameter values consistent with a low VPM, the triplet reproduces itself at a higher rate than the two-peak distribution, consequently mandating a slightly higher equilibrium VPM and the extinction of the ±35 degree pattern. In either case, populations of orientations reproduce and drive environmental changes (VPM/Vfree), that lead to changes in fitness and, ultimately, to a single symmetric pattern and velocity.

Conclusions

We have developed a comprehensive 2D model of lamellipodial protrusion based on the dendritic-nucleation/array-treadmilling mechanism, incorporating diffusion, stochastic kinetics, and elastic filament and PM models. A standard set of model parameter values were determined both directly from the literature and indirectly by using the criteria that model results of filament length, orientation patterns, and development times must be consistent with observed properties. Following these criteria, free barbed ends were protected from capping and allowed to branch at Rbr = 0.43/sec within a distance ε of 5.4 nm from the leading edge. This conferred the only directionality to the system.

The model accounts for the essential dynamic properties of the network, including a negative feedback loop, controlling the fraction of free barbed ends within ε, that maintained a constant SS protrusion rate VPM regardless of load. Under standard parameter values, the system converged from any ICs to a SS VPM/Vfree of 0.38 and a free barbed end count Nfb of 200 per μm. The filament pattern also self-organized, with only a ±35 degree pattern remaining at this terminal VPM. The system in fact displayed the hallmark adaptation to this pattern from distributions initially devoid of ±35 degree filaments. Any deviation from the symmetrical orientation increased the capping rate at the larger angle more than it increased the branching rate at the smaller angle. Changes in the direction of protrusion were thus corrected for by preferential reproduction of newly symmetrical patterns generated via branching angle “errors.”

Alternate parameter values that resulted in a SS VPM/Vfree < 0.20 (e.g., very low Rbr) resulted in a −70/0/70 degree pattern. Altering Vfree alone had no effect. Protection from capping within ε was absolutely required for realistic pattern formation, although branching localization was not. The pattern was robust with respect to PM surface and bending energies, but sensitive to filament bending lengths longer than ≈50 nm. These robustness and sensitivity traits describe a self-organizing filament network that resists environmental pressures in maintaining a characteristic orientation pattern and protrusion velocity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for valuable comments. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant GM 62431 (to G.G.B.) and a Northwestern University Pulmonary and Critical Care Division grant (to T.E.S.).

Abbreviations

- IC

initial condition

- SS

steady state

- PM

plasma membrane

- LE

leading edge

- EM

electron micrograph

- RF

rigid and flexible (beam-bending) filament model

- fil

filament.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701943104/DC1.

References

- 1.Miyata H, Hotani H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11547–11551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loisel TP, Boujemaa R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Nature. 1999;401:613–616. doi: 10.1038/44183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullins RD, Heuser JA, Pollard TD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stradal TE, Scita G. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlier MF, Laurent V, Santolini J, Melki R, Didry D, Xia GX, Hong Y, Chua NH, Pantaloni D. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchoin L, Pollard TD. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15538–15546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wear MA, Yamashita A, Kim K, Maeda Y, Cooper JA. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1531–1537. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchoin L, Amann KJ, Higgs HN, Marchand JB, Kaiser DA, Pollard TD. Nature. 2000;404:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35010008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottino JM. Nature. 2004;427:399. doi: 10.1038/427399a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maly IV, Borisy GG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181338798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verkhovsky AB, Chaga OY, Schaub S, Svitkina TM, Meister JJ, Borisy GG. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4667–4675. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atilgan E, Wirtz D, Sun SX. Biophys J. 2005;89:3589–3602. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.065383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberts JB, Odell GM. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:2054–2066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlsson AE. Biophys J. 2001;81:1907–1923. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75842-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlsson AE. Biophys J. 2003;84:2907–2918. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogilner A, Oster G. Biophys J. 1996;71:3030–3045. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79496-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mogilner A, Oster G. Biophys J. 2003;84:1591–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74969-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGrath JL, Tardy Y, Dewey CF, Jr, Meister JJ, Hartwig JH. Biophys J. 1998;75:2070–2078. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77649-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham VC, Krishnamurthi V, Taylor DL, Lanni F. Biophys J. 1999;77:1721–1732. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boal D. Mechanics of the Cell. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isambert H, Venier P, Maggs AC, Fattoum A, Kassab R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11437–11444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollard TD. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2747–2754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6631–6641. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchoin L, Pollard TD, Mullins RD. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schafer DA, Jennings PB, Cooper JA. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:169–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mejillano MR, Kojima S, Applewhite DA, Gertler FB, Svitkina TM, Borisy GG. Cell. 2004;118:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bear JE, Svitkina TM, Krause M, Schafer DA, Loureiro JJ, Strasser GA, Maly IV, Chaga OY, Cooper JA, Borisy GG, et al. Cell. 2002;109:509–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.