Abstract

We have used fast time-resolved infrared spectroscopy to characterize a series of organometallic methane and ethane complexes in solution at room temperature: W(CO)5(CH4) and M(η5 C5R5)(CO)2(L) [where M = Mn or Re, R = H or CH3 (Re only); and L = CH4 or C2H6]. In all cases, the methane complexes are found to be short-lived and significantly more reactive than the analogous n-heptane complexes. Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) and Re(Cp*)(CO)2(L) [Cp* = η5

C5R5)(CO)2(L) [where M = Mn or Re, R = H or CH3 (Re only); and L = CH4 or C2H6]. In all cases, the methane complexes are found to be short-lived and significantly more reactive than the analogous n-heptane complexes. Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) and Re(Cp*)(CO)2(L) [Cp* = η5 C5(CH3)5 and L = CH4, C2H6] were found to be in rapid equilibrium with the alkyl hydride complexes. In the presence of CO, both alkane and alkyl hydride complexes decay at the same rate. We have used picosecond time-resolved infrared spectroscopy to directly monitor the photolysis of Re(Cp*)(CO)3 in scCH4 and demonstrated that the initially generated Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4) forms an equilibrium mixture of Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4)/Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H within the first few nanoseconds (τ = 2 ns). The ratio of alkane to alkyl hydride complexes varies in the order Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6):Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H5)H > Re(Cp*)(CO)2(C2H6):Re(Cp*)(CO)2(C2H5)H ≈ Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4):Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H > Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4):Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H. Activation parameters for the reactions of the organometallic methane and ethane complexes with CO have been measured, and the ΔH‡ values represent lower limits for the CH4 binding enthalpies to the metal center of W

C5(CH3)5 and L = CH4, C2H6] were found to be in rapid equilibrium with the alkyl hydride complexes. In the presence of CO, both alkane and alkyl hydride complexes decay at the same rate. We have used picosecond time-resolved infrared spectroscopy to directly monitor the photolysis of Re(Cp*)(CO)3 in scCH4 and demonstrated that the initially generated Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4) forms an equilibrium mixture of Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4)/Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H within the first few nanoseconds (τ = 2 ns). The ratio of alkane to alkyl hydride complexes varies in the order Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6):Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H5)H > Re(Cp*)(CO)2(C2H6):Re(Cp*)(CO)2(C2H5)H ≈ Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4):Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H > Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4):Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H. Activation parameters for the reactions of the organometallic methane and ethane complexes with CO have been measured, and the ΔH‡ values represent lower limits for the CH4 binding enthalpies to the metal center of W CH4 (30 kJ·mol−1), Mn

CH4 (30 kJ·mol−1), Mn CH4 (39 kJ·mol−1), and Re

CH4 (39 kJ·mol−1), and Re CH4 (51 kJ·mol−1) bonds in W(CO)5(CH4), Mn(Cp)(CO)2(CH4), and Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4), respectively.

CH4 (51 kJ·mol−1) bonds in W(CO)5(CH4), Mn(Cp)(CO)2(CH4), and Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4), respectively.

Keywords: alkane, spectroscopy, supercritical fluid

There is considerable interest in sigma-bonded organometallic alkane complexes, particularly since they have been identified as key intermediates in the transition metal-mediated C H activation process (1–3). Although such complexes generally are very short-lived intermediates (4), they have been known for over 30 years. Early experiments involved the photolysis of complexes such as Cr(CO)6 and Fe(CO)5 to generate the unstable intermediates Cr(O)5 or Fe(CO)4 in low-temperature matrices, where coordination to cocondensed CH4 results in the formation of Cr(CO)5(CH4) and Fe(CO)5(CH4) (5, 6).

H activation process (1–3). Although such complexes generally are very short-lived intermediates (4), they have been known for over 30 years. Early experiments involved the photolysis of complexes such as Cr(CO)6 and Fe(CO)5 to generate the unstable intermediates Cr(O)5 or Fe(CO)4 in low-temperature matrices, where coordination to cocondensed CH4 results in the formation of Cr(CO)5(CH4) and Fe(CO)5(CH4) (5, 6).

Flash photolysis experiments have demonstrated that the photolysis of Cr(CO)6 in cyclohexane solution at room temperature forms Cr(CO)5(cyclohexane) (7). Subsequently, several examples of alkane complexes in solution have been reported, and studies on the mechanism of the C H activation process have clearly demonstrated the role of these complexes in oxidative addition reactions (1, 8, 9). Time-resolved infrared (TRIR) spectroscopy has proved to be a powerful tool for the study of metal carbonyl alkane complexes. Their reactivity decreases on going both across and down groups 5, 6, and 7 (10–12), and these observations led to the identification of a very long-lived alkane complex, Re(Cp)(CO)2(n-heptane) (Cp = η5

H activation process have clearly demonstrated the role of these complexes in oxidative addition reactions (1, 8, 9). Time-resolved infrared (TRIR) spectroscopy has proved to be a powerful tool for the study of metal carbonyl alkane complexes. Their reactivity decreases on going both across and down groups 5, 6, and 7 (10–12), and these observations led to the identification of a very long-lived alkane complex, Re(Cp)(CO)2(n-heptane) (Cp = η5 C5H5), which has a lifetime of ≈25 ms at room temperature (13). The relative stability of Re(Cp)(CO)2(alkane) complexes allowed Re(Cp)(CO)2(C5H10) to be observed at 180 K by NMR spectroscopy (14), and subsequent NMR studies have been carried out to determine the binding modes of a series of related alkanes to the Re(Cp′)(CO)2 moiety (15, 16).

C5H5), which has a lifetime of ≈25 ms at room temperature (13). The relative stability of Re(Cp)(CO)2(alkane) complexes allowed Re(Cp)(CO)2(C5H10) to be observed at 180 K by NMR spectroscopy (14), and subsequent NMR studies have been carried out to determine the binding modes of a series of related alkanes to the Re(Cp′)(CO)2 moiety (15, 16).

The activation of methane is of particular interest because of the potential of using this abundant hydrocarbon as both an energy source and chemical feedstock (17). Organometallic methane complexes have been characterized in low-temperature matrix isolation experiments (5, 6, 18). In solution, the existence of methane complexes has been inferred by examining product ratios and from the rates of C H activation and reductive elimination reactions in isotopic labeling experiments (19).

H activation and reductive elimination reactions in isotopic labeling experiments (19).

The lifetime of the alkane complexes depends strongly on the nature of the alkane, with cyclic alkanes tending to form longer-lived complexes than the corresponding linear alkanes do (12). Metal-alkane binding enthalpies have been determined by photoacoustic calorimetry (PAC) and TRIR spectroscopy for a range of group 6 [M(CO)5(heptane)] and group 7 [M(Cp)(CO)2(heptane)] complexes in solution, and these are found to range between 40 and 57 kJ·mol−1 (10, 20–24). Gas-phase TRIR studies have demonstrated that the shorter n-alkane species have progressively lower binding energies to the metal, with CH4 being the most weakly bound (25). The failure to identify W(CO)5(CH4) by TRIR in the gas phase led to the conclusion that the CH4 binding energy to the W(CO)5 fragment is <21 kJ·mol−1 (25). TRIR measurements on Cr(CO)6 in the gas phase demonstrated that photolysis produces Cr(CO)5. In the presence of CH4 (600 torr; 1 torr = 133 Pa), a 2-fold decrease in the rate of regeneration of Cr(CO)6 was interpreted to indicate a weak interaction between the Cr(CO)5 fragment and CH4, with an estimated binding enthalpy for Cr CH4 of 33 ± 8 kJ·mol−1 (26). We recently have used a combination of supercritical fluids and TRIR spectroscopy to characterize a series of organometallic noble gas complexes at room temperature (11), leading to the characterization of Re(iPrCp)(CO)(PF3)Xe by NMR (27). We have used a similar approach to characterize an organometallic methane complex in room temperature solution after the photolysis of Fe(CO)5 in supercritical methane (scCH4), where we observed 3Fe(CO)4 decaying into 1Fe(CO)4(CH4) with kobs = 5 ± 1 × 106 s−1 (28).

CH4 of 33 ± 8 kJ·mol−1 (26). We recently have used a combination of supercritical fluids and TRIR spectroscopy to characterize a series of organometallic noble gas complexes at room temperature (11), leading to the characterization of Re(iPrCp)(CO)(PF3)Xe by NMR (27). We have used a similar approach to characterize an organometallic methane complex in room temperature solution after the photolysis of Fe(CO)5 in supercritical methane (scCH4), where we observed 3Fe(CO)4 decaying into 1Fe(CO)4(CH4) with kobs = 5 ± 1 × 106 s−1 (28).

A number of theoretical studies on the coordination and activation of methane at metal centers also have been reported (29–33). Two of these studies are of particular interest to this work: (i) a study on the binding of CH4 to W(CO)5, which predicted the W CH4 binding enthalpy to be ≈18 kJ·mol−1 (30) and (ii) a paper on the interaction of CH4 with the Re(Tp)(CO)2 [Tp = Tris(pyrazolyl)borate] and Re(Cp)(CO)2 moieties, where the Re

CH4 binding enthalpy to be ≈18 kJ·mol−1 (30) and (ii) a paper on the interaction of CH4 with the Re(Tp)(CO)2 [Tp = Tris(pyrazolyl)borate] and Re(Cp)(CO)2 moieties, where the Re CH4 binding enthalpy was calculated to be 36 kJ·mol−1 for the formation of Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) from Re(Cp)(CO)2 and CH4 but with a low barrier to C

CH4 binding enthalpy was calculated to be 36 kJ·mol−1 for the formation of Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) from Re(Cp)(CO)2 and CH4 but with a low barrier to C H activation (33).

H activation (33).

In this article, we investigate the formation and reactivity of a series of organometallic methane and ethane complexes in solution at room temperature and provide a detailed study of an organometallic methane complex formed under these conditions. We have carried out a TRIR study of both group 6 and 7 transition metal carbonyls in scCH4 and liquid ethane (liqC2H6). A related paper by Ball et al. (34) in this issue reports an investigation on the photolysis of Re(Cp)(CO)2(PF3) in higher alkanes by TRIR and NMR, which shows a delicate balance between the coordination and activation of the alkane. Here, we also observe a balance between the coordination and activation of CH4 and C2H6 after interaction with Re(η5 C5R5)(CO)2 fragments (R = H or CH3).

C5R5)(CO)2 fragments (R = H or CH3).

Results and Discussion

TRIR Studies of W(CO)6 Photolysis in scCH4.

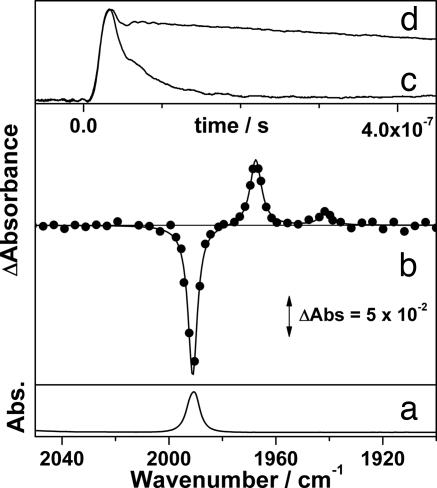

The TRIR difference spectrum obtained 1 μs after photolysis (355 nm) of W(CO)6 (1) in scCH4 (4,000 psi, 296 K) in the presence of CO (17 psi) is shown in Fig. 1b. It is clear that the parent ν(CO) band at 1,991 cm−1 is bleached, and two transient bands are formed at 1,968 and 1,942 cm−1. In the presence of CO, these transient bands decay at the same rate (kobs = 4.4 ± 0.1 × 105 s−1) as the parent band reforms. By comparison to previous matrix isolation (5) and TRIR experiments (35), these transient bands can be assigned to W(CO)5(CH4) (2). The observed rate constant for the decay of 2 depends linearly on the CO concentration, affording the second-order rate constant for the reaction of 2 with CO in scCH4 (kCO = 7.8 ± 0.8 × 106 dm3·mol−1·s−1, 298 K). W(CO)5(CH4) is significantly more reactive (3–15 times) than other previously reported W(CO)5(alkane) complexes (12). However, the rate of the alkane-CO substitution still is significantly below the diffusion-controlled rate in scCH4 (≈8 × 1011 dm3·mol−1·s−1, estimated from the Stokes–Einstein equations). We have carried out experiments in scAr to provide proof of the coordination of methane to W(CO)5 in solution. Photolysis of 1 in scAr (5,100 psi, 296 K) under a low concentration of CO (3 psi) generates two transient bands at 1,969 and 1,941 cm−1, which rapidly decay (kobs = 1.2 ± 0.6 × 107 s−1) (Fig. 1c). Organometallic Ar complexes have been identified in low-temperature matrices (5), and theoretical studies have predicted that Ar binds to W(CO)5 (36). We tentatively assign these bands to W(CO)5Ar; however, further work is required to substantiate the nature of this transient species. When the experiment is repeated in the presence CH4 (200 psi), the transient bands are observed at 1,945 and 1,970 cm−1, and they decay on a much longer time scale (kobs = 9.0 ± 2.0 × 105 s−1) (Fig. 1d). The increased lifetime of the transient in scAr doped with CH4 indicates that 2 is formed in scAr. This work provides a detailed study of the reactivity of an organometallic methane complex (2) in solution at room temperature.

Fig. 1.

IR spectra and TRIR decay traces of W(CO)5(L) (L = Ar, CH4) in supercritical fluid solutions. (a) FTIR of W(CO)6 in scCH4 (4,000 psi, 296 K) and CO (17 psi). (b) TRIR difference spectrum of the same solution 1 μs after photolysis (355 nm). (c and d) Decay traces of the transient (1,969 cm−1) after photolysis of W(CO)6 in scAr (5,100 psi) with CO (3 psi) (c) and scAr (4,900 psi) with CH4 (200 psi) and CO (3 psi) (d).

We have investigated the coordination of CH4 to W(CO)5 further by determining the activation parameters for the reaction of W(CO)5(CH4) with CO in scCH4 from variable-temperature TRIR experiments. The interpretation of activation parameters for the ligand substitution reaction of an alkane complex with CO requires great care, particularly because the mechanism could be considered to be associative, dissociative, or interchange in nature. The reaction of 2 with CO in scCH4 is faster (3.4 times) than that of the analogous n-heptane complex. However, the value of ΔH‡ for the reaction of 2 with CO is found to be greater that that of the corresponding reaction for the n-heptane complex (Table 1). The ΔH‡ value (30 ± 2 kJ·mol−1) for the reaction of 2 with CO can be used as a lower limit for the W CH4 binding enthalpy in scCH4. It is interesting to compare this result with previous calculations (30), which predict a W

CH4 binding enthalpy in scCH4. It is interesting to compare this result with previous calculations (30), which predict a W CH4 interaction of 18 kJ·mol−1, and with gas-phase TRIR experiments, which estimate a Cr

CH4 interaction of 18 kJ·mol−1, and with gas-phase TRIR experiments, which estimate a Cr CH4 bond-dissociation energy of 33 ± 8 kJ·mol−1 (26). Clearly, there is a significant W

CH4 bond-dissociation energy of 33 ± 8 kJ·mol−1 (26). Clearly, there is a significant W CH4 interaction in solution at room temperature. We previously have shown that Re(Cp)(CO)2(heptane) is ≈700 times longer-lived than W(CO)5(heptane) is (13). In an attempt to produce long-lived complexes of the lighter alkanes, we have investigated the photochemistry of M(Cp)(CO)3 (M = Mn or Re) in scCH4 and liqC2H6.

CH4 interaction in solution at room temperature. We previously have shown that Re(Cp)(CO)2(heptane) is ≈700 times longer-lived than W(CO)5(heptane) is (13). In an attempt to produce long-lived complexes of the lighter alkanes, we have investigated the photochemistry of M(Cp)(CO)3 (M = Mn or Re) in scCH4 and liqC2H6.

Table 1.

Rate constants and activation parameters for the reaction of a series of organometallic alkane complexes with CO in supercritical (for CH4) and liquid (for other alkanes) solutions

| Complex | kCO, dm3·mol−1·s−1 at 298 K | ΔH‡, kJ·mol−1 |

|---|---|---|

| W(CO)5(n-C7H16)† | 2.3 (±0.2) × 106 | 20 ± 2 |

| W(CO)5(CH4) (2) | 7.8 (±0.2) × 106 | 30 ± 2 |

| CpRe(CO)2(n-C7H16)§ | 2.5 (±0.2) × 103 | 46 ± 2 |

| CpRe(CO)2(C5H10)§ | 1.2 (±0.2) × 103 | 32 ± 2 |

| CpMn(CO)2(n-C7H16)§ | 8.0 (±0.6) × 105 | 36 ± 2 |

| CpMn(CO)2(C5H10)§ | 2.5 (±0.4) × 105 | 24 ± 2 |

| CpMn(CO)2(CH4) (4) | 1.6 (±0.3) × 107 | 39 ± 2 |

| CpMn(CO)2(C2H6) (5) | 2.6 (±0.2) × 106 | 36 ± 2 |

| CpRe(CO)2(CH4) (7) | 2.7 (±0.4) × 104 | 51 ± 5 |

| CpRe(CO)2(C2H6)¶ | 6.9 (±0.5) × 103 | 43 ± 2 |

| Cp*Re(CO)2(CH4) (10) | 5.0 (±0.3) × 104 | 47 ± 2 |

| Cp*Re(CO)2(C2H6) (11) | 2.6 (±0.1) × 104 | 43 ± 2 |

TRIR Studies of Mn(Cp)(CO)3 in scCH4 and liqC2H6.

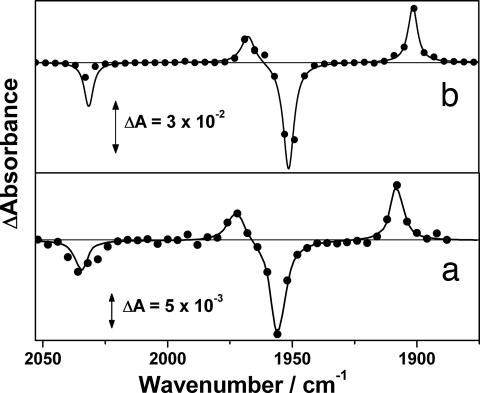

The TRIR difference spectra after photolysis (355 nm) of Mn(Cp)(CO)3 (3) in scCH4 (4,000 psi, 298 K) and liqC2H6 (1,600 psi, 297 K) both containing CO (60 psi) are shown in Fig. 2. In both cases, the parent is bleached, and two new transient bands at lower energy are produced. These transients are assigned to Mn(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) (4) and Mn(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6) (5) in scCH4 or liqC2H6, respectively, by comparison to known Mn(Cp)(CO)2(alkane) complexes (37, 38). These transients decay in the presence of CO to reform 3 (for 4, kobs = 2.5 ± 0.2 × 106 s−1 and kCO = 1.6 ± 0.3 × 107 dm3·mol−1·s−1; for 5, kobs = 4.9 ± 0.1 × 105 s−1 and kCO = 2.6 ± 0.2 × 106 dm3·mol−1·s−1, all at 298 K).§ These ethane and methane complexes also are significantly more reactive (3–20 times) toward CO than the analogous longer-chain n-heptane complexes are (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

TRIR difference spectra of Mn(Cp)(CO)3 photolysis (355 nm) in scCH4 (4,000 psi) with CO (60 psi) at 298 K (a) and C2H6 (1,600 psi) with CO (60 psi) at 297 K (b). The difference spectra in a and b were recorded at 120 ns and 3 μs, respectively, after photolysis.

The activation parameters for the reaction of 4 and 5 with CO to reform 3 have been investigated. The ΔH‡ value determined for 4 (39 ± 2 kJ·mol−1) again provides an estimate of the lower limit of the Mn CH4 binding enthalpy. Mn(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6) (5) is found to be significantly less reactive than 4 is to CO substitution, indicating an increased binding strength of C2H6 to manganese compared with CH4. However, the smaller value of ΔH‡ (36 ± 2 kJ·mol−1) suggests that this value is a considerable underestimate of the Mn

CH4 binding enthalpy. Mn(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6) (5) is found to be significantly less reactive than 4 is to CO substitution, indicating an increased binding strength of C2H6 to manganese compared with CH4. However, the smaller value of ΔH‡ (36 ± 2 kJ·mol−1) suggests that this value is a considerable underestimate of the Mn C2H6 binding enthalpy in 5. In principle, the values of ΔS‡ from our activation parameters would shed light on whether this underestimate is attributable to changes in the reaction mechanism that might be occurring. However, interpretation of such values is problematic because of the potentially large errors in determining the ΔS‡ values and possible entropy/enthalpy compensation effects (40).

C2H6 binding enthalpy in 5. In principle, the values of ΔS‡ from our activation parameters would shed light on whether this underestimate is attributable to changes in the reaction mechanism that might be occurring. However, interpretation of such values is problematic because of the potentially large errors in determining the ΔS‡ values and possible entropy/enthalpy compensation effects (40).

Photolysis of Re(Cp)(CO)3 in scCH4.

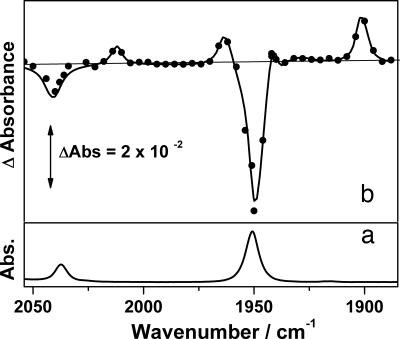

The fragment Re(Cp)(CO)2 produces long-lived alkane complexes with the higher alkanes, and we previously have reported the formation of Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6) in a room temperature solution (41). The TRIR spectrum of Re(Cp)(CO)3 (6) in scCH4 (4,000 psi, 294 K) in the presence of CO (90 psi) obtained 20 μs after the laser flash shows that the parent ν(CO) bands at 1,951 and 2,038 cm−1 are bleached, and four new transient bands are produced at 2,012, 1,963, 1,942, and 1,902 cm−1 (Fig. 3). These transient peaks cannot be assigned to a single mononuclear CO loss intermediate as such a species cannot have more than two ν(CO) bands. The production of four new transient bands may indicate that more than one primary photoproduct is produced. In the presence of CO, all four bands decay at the same rate as the parent bands reform (kobs = 6.41 ± 0.08 × 103 s−1).¶ In the absence of CO, Re(Cp)(CO)2(alkane) is known to react with Re(Cp)(CO)3 to form Re2(Cp)2(CO)5 (42, 43). The new ν(CO) bands observed in this study are not attributable to this dimeric species. The two bands at 1,902 and 1,963 cm−1 can be assigned to the solvated dicarbonyl species Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) (7) by comparison to previous low-temperature IR and room temperature TRIR experiments (38, 44). The bathochromic shift in the ν(CO) bands compared with the parent species is consistent with loss of the π-acceptor ligand. Furthermore, the two bands at 1,942 and 2,012 cm−1 have undergone a hypsochromic shift in comparison with 7, which is consistent with loss of a CO ligand and oxidation of the metal centre. This finding leads us to the tentative assignment of the bands at 1,942 and 2,012 cm−1 to the C H activated species Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H (8). The activation of C

H activated species Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H (8). The activation of C H bonds by the related fragment Re(Cp*)(CO)2 previously has been observed in the study of fluorinated arenes (45). The assignment of 7 and 8 is supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. We have carried out similar calculations to those previously reported (33) and have computed the IR frequencies of the ν(CO) vibrations. We have compared these gas-phase calculated values to the experimentally obtained band positions Re(Cp)(CO)3 (TRIR: 1,951 and 2,038 cm−1; DFT: 2,023 and 2,101 cm−1), Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H (TRIR: 1,942 and 2,012 cm−1; DFT: 2,014 and 2,078 cm−1), and Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) (TRIR: 1,902 and 1,963 cm−1; DFT: 1,979 and 2,034 cm−1). Although the absolute values are not comparable, there is a very good agreement between the trends in the calculated values and those observed in the TRIR experiments. We have not observed the ν(M

H bonds by the related fragment Re(Cp*)(CO)2 previously has been observed in the study of fluorinated arenes (45). The assignment of 7 and 8 is supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. We have carried out similar calculations to those previously reported (33) and have computed the IR frequencies of the ν(CO) vibrations. We have compared these gas-phase calculated values to the experimentally obtained band positions Re(Cp)(CO)3 (TRIR: 1,951 and 2,038 cm−1; DFT: 2,023 and 2,101 cm−1), Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H (TRIR: 1,942 and 2,012 cm−1; DFT: 2,014 and 2,078 cm−1), and Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4) (TRIR: 1,902 and 1,963 cm−1; DFT: 1,979 and 2,034 cm−1). Although the absolute values are not comparable, there is a very good agreement between the trends in the calculated values and those observed in the TRIR experiments. We have not observed the ν(M H) band of 8, which would be expected to be present in the region of study, and as expected our DFT calculations have indicated that the ν(M

H) band of 8, which would be expected to be present in the region of study, and as expected our DFT calculations have indicated that the ν(M H) bands of 8 are much lower in intensity than the ν(CO) bands. The observation of both the transient species 7 and 8 is in contrast to the photolysis of 3 in scCH4 which yielded only 4. It is interesting to compare these results with the study of the interaction of dihydrogen with the M(Cp)(CO)2 moiety. A nonclassical dihydrogen complex, Mn(Cp)(CO)2(η2

H) bands of 8 are much lower in intensity than the ν(CO) bands. The observation of both the transient species 7 and 8 is in contrast to the photolysis of 3 in scCH4 which yielded only 4. It is interesting to compare these results with the study of the interaction of dihydrogen with the M(Cp)(CO)2 moiety. A nonclassical dihydrogen complex, Mn(Cp)(CO)2(η2 H2), was observed for manganese, and for rhenium, oxidative addition of dihydrogen led to formation of the dihydride complex (46). Similarly, the reaction of Re(Cp)(CO)2 with triethylsilane (SiEt3H) forms Re(Cp)(CO)2(SiEt3)H, whereas reaction with the analogous manganese complex generates a η2

H2), was observed for manganese, and for rhenium, oxidative addition of dihydrogen led to formation of the dihydride complex (46). Similarly, the reaction of Re(Cp)(CO)2 with triethylsilane (SiEt3H) forms Re(Cp)(CO)2(SiEt3)H, whereas reaction with the analogous manganese complex generates a η2 Si

Si H complex (47).

H complex (47).

Fig. 3.

IR spectra of Re(Cp)(CO)3 in scCH4. (a) FTIR spectrum of Re(Cp)(CO)3 in scCH4 (4,000 psi) with CO (90 psi) at 294 K. (b) TRIR difference spectra of same solution 20 μs after photolysis (266 nm).

In our experiments, the fact that 7 and 8 decay at the same rate suggests that these two species are in rapid equilibrium. We have varied both the temperature and the concentration of CO in scCH4 solution, and accordingly, under all measured conditions, both sets of bands decay at the same rate. The observed rate constant for the decay of 7 and 8 increased linearly with CO concentration (kCO = 2.7 ± 0.4 × 104 dm3·mol−1·s−1, 298 K). For a system at equilibrium, it may be possible to vary product distribution by varying the temperature. Variable temperature experiments over a small temperature range (293–333 K) showed no detectable difference in product distribution larger than the signal noise, which indicates that the energetic difference between 7 and 8 is relatively small, and it may only be possible to detect such a difference over a large temperature range. Attempts to increase the temperature range of the experiments were hampered either by the high pressures involved or at low temperature by poor solubility. The assignment of a fast equilibrium between 7 and 8 is consistent with previous theoretical work (33) in which it was calculated that there was a small barrier to C H activation of CH4 in 7 and the difference in enthalpy between 7 and 8 was reported to be only ≈4 kJ·mol−1. The presence of a rapid thermal equilibrium between a sigma-complex and an oxidative addition product previously has been observed for the addition of dihydrogen to the Nb(Cp)(CO)3 moiety in which both Nb(Cp)(CO)3(η2

H activation of CH4 in 7 and the difference in enthalpy between 7 and 8 was reported to be only ≈4 kJ·mol−1. The presence of a rapid thermal equilibrium between a sigma-complex and an oxidative addition product previously has been observed for the addition of dihydrogen to the Nb(Cp)(CO)3 moiety in which both Nb(Cp)(CO)3(η2 H2) and Nb(Cp)(CO)3H2 were observed on the nanosecond time scale (10).

H2) and Nb(Cp)(CO)3H2 were observed on the nanosecond time scale (10).

Photolysis of Re(Cp*)(CO)3 in scCH4.

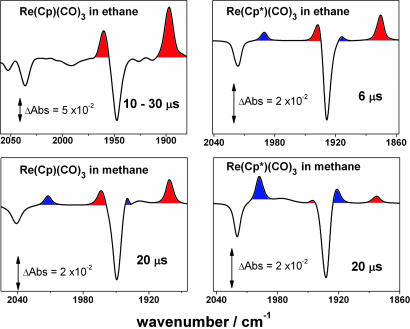

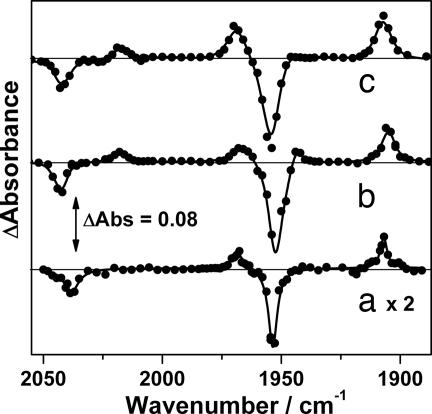

We have investigated the interesting equilibrium between methane and methyl hydride complexes further by repeating these measurements using Re(Cp*)(CO)3 (9), where there is increased electron density on the rhenium metal center. Photolysis (266 nm) of 9 was studied in solutions of both methane (4,000 psi, 298 K) and ethane (1,660 psi, 294 K), both containing CO (90 and 60 psi, respectively). The TRIR difference spectrum in scCH4 showed a ν(CO) band pattern similar to that seen for the photolysis of Re(Cp)(CO)3 (6), indicating the presence of both Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4) (10) and Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H (11) (Fig. 4). The complex trans-Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H previously has been synthesized, allowing us to assign 11 to cis-Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H (48). These results can be compared directly with the photolysis of 6, and there is a noticeable increase in the proportion of the oxidative addition product 11 relative to the organometallic methane complex 10.

Fig. 4.

TRIR difference spectra after photolysis of indicated species. Experiments were carried out in the presence of CO with 1,660 psi ethane or 4,000 psi methane. Lorentzian fit lines of the experimental data are shown. Red shaded areas indicate ν(CO) bands of the alkane complexes, Re(Cp)(CO)2(CnH2n+2), and blue areas indicate the C H activated complexes, Re(Cp)(CO)2(CnH2n+1)H. The Re(Cp)(CO)3 in ethane spectrum is adapted from ref. 41.

H activated complexes, Re(Cp)(CO)2(CnH2n+1)H. The Re(Cp)(CO)3 in ethane spectrum is adapted from ref. 41.

Photolysis of 6 in liqC2H6 only generates detectable amounts of Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6) (41), whereas photolysis of 9 in ethane solution led to the formation of both Re(Cp*)(CO)2(C2H6) (12) and a low concentration of Re(Cp*)(CO)2(C2H5)H (13). For 10/11 and 12/13, the four photoproduct bands for each solution decayed at indistinguishable rates, indicating the presence of rapid equilibria. The rates of reaction of CO with 10/11 and 12/13 were found to be significantly faster than those seen after the photolysis of 6 (10/11: kCO = 5.0 ± 0.3 ×104 dm3·mol−1·s−1; 12/13: kCO = 2.7 ± 0.1 ×104 dm3·mol−1·s−1, both at 298 K). The faster rate for the reaction of 10/11 with CO relative to the corresponding reaction of 7/8 is consistent with a previous study on the lifetime of Mn(η5 C5R5)(CO)2(n-heptane) (R = H or CH3) toward small molecules in which faster rates of ligand substitution were observed for R = CH3 (49).

C5R5)(CO)2(n-heptane) (R = H or CH3) toward small molecules in which faster rates of ligand substitution were observed for R = CH3 (49).

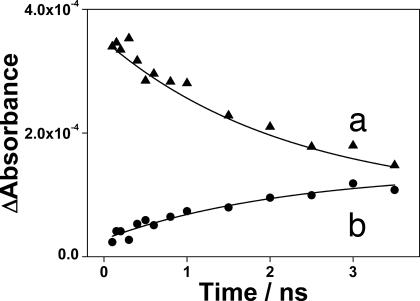

We also have monitored the photolysis of 9 in scCH4 by using picosecond TRIR (ps-TRIR) to investigate the formation of the equilibrium between alkane and alkyl hydride complexes (Fig. 5). This system was chosen because of the increased concentration of the C H activated species, which allowed for the direct monitoring of the establishment of the equilibrium between 10 and 11. Initially after photolysis, the parent ν(CO) bands are bleached, and two strong transient bands at 1,943 and 1,883 cm−1 corresponding to Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4) (10) are apparent (Fig. 5b). Also present at early times are additional ν(CO) bands (2,010, 1,986, and 1,919 cm−1), which decay rapidly (kobs = 1.7 ± 0.3 × 1010 s−1) as the parent species partially reforms. Previous studies on the photolysis of Re(Cp)(CO)3 in silane solutions also have observed similar short-lived species, which were assigned to the decay of the vibrationally excited ground-state molecule (47). The ν(CO) bands of 10 then are observed to decay partially, concurrent with the rise of the bands of Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H (11) at 1,998 and 1,923 cm−1, yielding an approximate rate for the activation of CH4 and establishment of the equilibrium between 10 and 11 (kobs = 5 ± 2 × 108 s−1) (Fig. 6).

H activated species, which allowed for the direct monitoring of the establishment of the equilibrium between 10 and 11. Initially after photolysis, the parent ν(CO) bands are bleached, and two strong transient bands at 1,943 and 1,883 cm−1 corresponding to Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4) (10) are apparent (Fig. 5b). Also present at early times are additional ν(CO) bands (2,010, 1,986, and 1,919 cm−1), which decay rapidly (kobs = 1.7 ± 0.3 × 1010 s−1) as the parent species partially reforms. Previous studies on the photolysis of Re(Cp)(CO)3 in silane solutions also have observed similar short-lived species, which were assigned to the decay of the vibrationally excited ground-state molecule (47). The ν(CO) bands of 10 then are observed to decay partially, concurrent with the rise of the bands of Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H (11) at 1,998 and 1,923 cm−1, yielding an approximate rate for the activation of CH4 and establishment of the equilibrium between 10 and 11 (kobs = 5 ± 2 × 108 s−1) (Fig. 6).

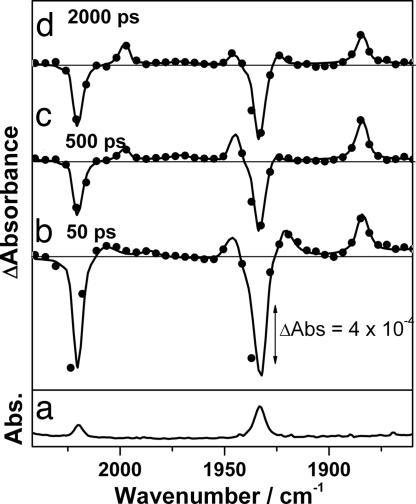

Fig. 5.

ps-TRIR spectra showing the formation of Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH3)H. (a) FTIR of Re(Cp*)(CO)3 in scCH4 (4,000 psi) with CO (90 psi) at ≈298 K. (b–d) TRIR difference spectra of the same solution at 50 ps (b), 500 ps (c), and 2,000 ps (d) after photolysis (267 nm).

Fig. 6.

Kinetic traces of ν(CO) bands of Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH4) (1,943 cm−1) (a) and Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CH3)H (1,998 cm−1) (b) after photolysis (267 nm) of Re(Cp*)(CO)3 in scCH4.

Kinetic Isotopic Effects.

The activation of CH4 by Re(Cp)(CO)2 and Re(Cp*)(CO)2 has been investigated by using CD4. Unfortunately, experiments in scCD4 were prohibitively expensive, and we therefore have performed experiments in scAr doped with either CH4 or CD4. Photolysis of 6 in pure scAr only generates two CO bands at lower energy than those of 6, which are extremely short-lived even in the presence of a low concentration of CO (1 psi, kobs = 2.0 ± 0.2 × 106 s−1) (Fig. 7a). The observed rate constant for the decay of this transient depends linearly on the CO concentration (kCO = 9.0 ± 0.9 × 108 dm3·mol−1·s−1, 298 K). This rate is below the expected diffusion-controlled rate (5 × 1011 dm3·mol−1·s−1, estimated from the Stokes–Einstein equations), supporting the tentative assignment of this species to the solvated Ar complex. The photolysis of 6 in scAr (5,000 psi) doped with CH4 (200 psi) and CO (11 psi) also has been investigated (Fig. 7b). It is clear that the results in scAr doped with CH4 are very similar to those obtained in pure scCH4 and that the same four transient bands are observed, which are assigned to 7 and 8 in scAr. The rate of decay of 7 and 8 is significantly slower (kobs = 2.20 ± 0.05 ×104 s−1, 302 K) than the observed rate of decay of the transient in pure scAr. The experiment was repeated by using CD4 rather than CH4. In this experiment, the ν(CO) bands of Re(Cp)(CO)2(CD4) (14) and Re(Cp)(CO)2(CD3)D (15) are identifiable (Fig. 7c). A small shift (0 to 5 cm−1) in the bands of 14/15 relative to 7/8 in scAr is observed. The observed rate of decay of the equilibrium mixture of 14/15 in scAr is greater (kobs = 3.49 ± 0.05 × 104 s−1, 302 K) than that of 7/8 in scAr. There is a significant inverse kinetic isotope effect (kH/kD = 0.6 ± 0.1). We also find an inverse kinetic isotope effect (kH/kD = 0.4 ± 0.1) for the decay of Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CD4) (16) and Re(Cp*)(CO)2(CD3)D (17). An observed inverse kinetic isotope for the reductive elimination of an alkane from an alkyl hydride complex often is taken as an indicator of the presence of an alkane sigma-complex intermediate in the reductive elimination pathway (19, 50), which is consistent with our experimental assignments of the alkane/alkyl hydride equilibrium.

Fig. 7.

TRIR difference spectra of Re(Cp)(CO)3 photolysis (266 nm) in scAr (5,060 psi, 298 K) with CO (10 psi) (a), scAr (5,000 psi, 298 K) doped with CH4 (200 psi) and CO (11 psi) (b), and scAr (5,000 psi, 298 K) doped with CD4 (200 psi) and CO (11 psi) (c). Spectra were recorded 80 ns (a), 10 μs (b), and 10 μs (c) after photolysis.

Activation Parameters.

Examination of the rate constant for the reaction of the equilibrium mixture 7/8 or 10/11 with CO indicates once more that the methane complexes 7 and 10 are significantly more reactive than the analogous heptane and cyclopentane complexes are (Table 1). The values of ΔH‡ obtained for the reactions of 7/8 (51 ± 5 kJ·mol−1) and 10/11 (47 ± 2 kJ·mol−1) with CO in scCH4 are again a lower limit of the Re CH4 binding enthalpy. Previously, the lower limit of the Re

CH4 binding enthalpy. Previously, the lower limit of the Re heptane binding enthalpy has been reported to be 57 kJ·mol−1 (23). Other lower limits for the Re

heptane binding enthalpy has been reported to be 57 kJ·mol−1 (23). Other lower limits for the Re alkane binding enthalpy have been in the range of 32–46 kJ·mol−1 (38). The ΔH‡ for the reaction of Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6) with CO in liqC2H6 (43 ± 2 kJ·mol−1) (41) is the same as that of the corresponding reaction of 12/13 (43 ± 2 kJ·mol−1). These ΔH‡ values clearly are lower than those for the corresponding reactions of 7/8 and 10/11 with CO.

alkane binding enthalpy have been in the range of 32–46 kJ·mol−1 (38). The ΔH‡ for the reaction of Re(Cp)(CO)2(C2H6) with CO in liqC2H6 (43 ± 2 kJ·mol−1) (41) is the same as that of the corresponding reaction of 12/13 (43 ± 2 kJ·mol−1). These ΔH‡ values clearly are lower than those for the corresponding reactions of 7/8 and 10/11 with CO.

Conclusions

In this paper, the observation of methane C H bond activation in solution at room temperature has been described. Using TRIR spectroscopy, we have provided examples of organometallic methane and ethane alkane complexes under such conditions. The organometallic methane and ethane complexes are all significantly more reactive than the previously reported analogous longer-chain alkane complexes. Despite this finding, we do observe a significant interaction between methane and all of the metal complex fragments examined, and it has been shown that methane has a surprisingly strong bond to rhenium in solution, with a lower limit of the binding enthalpy found to be 51 ± 5 kJ·mol−1 in Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4). There is clearly more to learn about organometallic methane complexes and it is likely that fast TRIR will prove useful for this purpose.

H bond activation in solution at room temperature has been described. Using TRIR spectroscopy, we have provided examples of organometallic methane and ethane alkane complexes under such conditions. The organometallic methane and ethane complexes are all significantly more reactive than the previously reported analogous longer-chain alkane complexes. Despite this finding, we do observe a significant interaction between methane and all of the metal complex fragments examined, and it has been shown that methane has a surprisingly strong bond to rhenium in solution, with a lower limit of the binding enthalpy found to be 51 ± 5 kJ·mol−1 in Re(Cp)(CO)2(CH4). There is clearly more to learn about organometallic methane complexes and it is likely that fast TRIR will prove useful for this purpose.

Materials and Methods

W(CO)6 (99%; Strem Chemicals, Newburyport, MA), Mn(Cp)(CO)3 (Sigma–Aldrich), Re(Cp)(CO)3 (99%; Strem Chemicals), Re(Cp*)(CO)3 (99%; Strem Chemicals), CH4 (research grade 99.995%; BOC Special Gases, Whitby, ON, Canada), C2H6 (technical grade 99.95%; Air Products, Allentown, PA), Ar (pure shield grade; BOC), CD4 (99 atom % D; Sigma–Aldrich), and CO (premier grade; Air Products) all were used as received.

Two different types of instrumentation were used to obtain TRIR data. Details of the diode laser-based TRIR apparatus have been described elsewhere (51). Briefly, the IR source, a continuous wave IR diode laser, was used to monitor the change in IR transmission at one IR frequency after UV excitation of the sample. Spectra were built up in a “point-by-point” fashion. ps-TRIR studies were performed on the PIRATE apparatus at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (Oxfordshire, U.K.), which also has been described in detail elsewhere (52). Supercritical and high-pressure liquid solutions for the experiments were prepared in a manner similar to that described in a previous study (28).

DFT calculations were performed by using Gaussian 03 (53) with the B3LYP hybrid functional (54–56) and the 6–311(G)(d,p) basis functions for all atoms except Re, for which the LanL2DZ ECP basis set augmented with “f” functions by using the contraction coefficients of Ehlers et al. (57–60) was used.

Supporting Information.

Further results, details of the calculations, and experimental procedures can be found in supporting information (SI) Figs. 8–13, SI Tables 2 and 3, and SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. K. Ronayne and Dr. M. Towrie of the Central Laser Facility (Rutherford Appleton Laboratory) and C. M. Brookes (Nottingham University) for assistance with the ps-TRIR experiment. We thank the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council of the U.K. (M.W.G.), Fujifilm Colorants Ltd. (A.J.C.), Nottingham University (D.C.G.), and the European Union (P.P. and O.S.J.) for financial support.

Abbreviations

- TRIR

time-resolved infrared

- scCH4,

supercritical methane

- liqC2H6,

liquid ethane

- DFT

density functional theory

- ps-TRIR

picosecond TRIR.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.A.L. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0610567104/DC1.

The second-order rate constant in liqC2H6 was calculated by assuming that all of the CO was soluble (39). Extrapolation of the second-order rate constant obtained in scC2H6, where there is complete miscibility between CO and C2H6 at 298 K, leads to an equivalent kCO value within the experimental error.

At long time delays, further ν(CO) bands at ≈1,990 and 1,929 cm−1 corresponding to Re2(Cp)2(CO)5 are observed, indicating the presence of a second minor decay route.

References

- 1.Bromberg SE, Yang H, Asplund MC, Lian T, McNamara BK, Kotz KT, Yeston JS, Wilkens M, Frei H, Bergman RG, et al. Science. 1997;278:260–263. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crabtree RH. J Organomet Chem. 2004;689:4083–4091. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Nature. 2002;417:507–514. doi: 10.1038/417507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall C, Perutz RN. Chem Rev. 1996;96:3125–3146. doi: 10.1021/cr9502615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perutz RN, Turner JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:4791–4800. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poliakoff M, Turner JJ. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1974;20:2276–2285. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly JM, Hermann H, von Gustorf EK. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1973:105–106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bengali AA, Schultz RH, Moore CB, Bergman RG. J Am Chem. 1994;116:9585–9589. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lian T, Bromberg SE, Yang H, Proulx G, Bergman RG, Harris CB. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3769–3770. [Google Scholar]

- 10.George MW, Haward MT, Hamley PA, Hughes C, Johnson FPA, Popov VK, Poliakoff M. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2286–2299. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Childs GI, Grills DC, Sun XZ, George MW. Pure Appl Chem. 2001;73:443–447. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breheny CJ, Kelly JM, Long C, O'Keefe S, Pryce MT, Russell G, Walsh MM. Organometallics. 1998;17:3690–3695. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun XZ, Grills DC, Nikiforov SM, Poliakoff M, George MW. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7521–7525. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geftakis S, Ball GE. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9953–9954. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawes DJ, Geftakis S, Ball GE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4134–4135. doi: 10.1021/ja044208m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawes DJ, Darwish TA, Clark T, Harper JB, Ball GE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4486–4490. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crabtree RH. Chem Rev. 1995;95:987–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billups WE, Chang SC, Hauge RH, Margrave JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2039–2041. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones WD. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:140–146. doi: 10.1021/ar020148i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morse JM, Parker GH, Burkey TJ. Organometallics. 1989;8:2471–2474. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiao TJ, Leu GL, Farrell GJ, Burkey TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4960–4965. doi: 10.1021/ja003165g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkey TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8329–8333. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bengali AA. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:4989–4992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hester DM, Sun J, Harper AW, Yang GK. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5234–5240. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown CE, Ishikawa Y, Hackett PA, Rayner DM. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2530–2536. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells JR, House PG, Weitz E. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:8343–8351. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ball GE, Darwish TA, Geftakis S, George MW, Lawes DJ, Portius P, Rourke JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1853–1858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406527102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portius P, Yang J, Sun XZ, Grills DC, Matousek P, Parker AW, Towrie M, George MW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10713–10720. doi: 10.1021/ja048411t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegbahn PEM. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:1487–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaric S, Hall MB. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:4646–4652. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heiberg H, Gropen O, Swang O. Int J Quant Chem. 2003;92:391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Almeida KJ, Cesar A. Organometallics. 2006;25:3407–3416. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergman RG, Cundari TR, Gillespie AM, Gunnoe TB, Harman WD, Klinckman TR, Temple MD, White DP. Organometallics. 2003;22:2331–2337. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ball GE, Brookes CM, Cowan AJ, Darwish TA, George MW, Kawanami HK, Portius P, Rourke JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610212104. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermann H, Grevels FW, Henne A, Schaffner K. J Phys Chem. 1982;86:5151–5154. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehlers AW, Frenking G, Baerends EJ. Organometallics. 1997;16:4896–4902. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rest AJ, Sodeau JR, Taylor DJ. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1978;6:651–656. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Childs GI, Colley CS, Dyer J, Grills DC, Sun XZ, Yang JX, George MW. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 2000;12:1901–1906. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trust DB, Kurata F. Am Inst Chem Eng J. 1971;17:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallicchio E, Kubo MM, Levy RM. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4526–4527. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuimova MK, Alsindi WZ, Dyer J, Grills DC, Jina OS, Matousek P, Parker AW, Portius P, Sun XZ, Towrie M, et al. Dalton Trans. 2003;21:3996–4006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bitterwolf TE, Lott KA, Rest AJ, Mascetti J. J Organomet Chem. 1991;419:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foust AS, Hoyano JK, Graham WAG. J Organomet Chem. 1971;32:C65–C66. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chetwynd-Talbot J, Grebenik P, Perutz RN, Powell MHA. Inorg Chem. 1983;22:1675–1684. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carbo JJ, Eisenstein O, Higgitt CL, Klahn AH, Maseras F, Oelckers B, Perutz RN. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 2001;9:1452–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howdle SM, Poliakoff M. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1989;16:1099–1101. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang H, Asplund MC, Kotz KT, Wilkens MJ, Frei H, Harris CB. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10154–10165. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ball RG, Campen AK, Graham WAG, Hamley PA, Kazarian SG, Ollino MA, Poliakoff M, Rest AJ, Sturgeoff L, Whitwell I. Inorg Chim Acta. 1997;259:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson FPA, George MW, Bagratashvili VN, Vereshchagina L, Poliakoff M. J Chem Soc Mendeleev Commun. 1991:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Janak KE, Churchill DG, Parkin G. Chem Commun. 2003;1:22–23. doi: 10.1039/b209684f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.George MW, Poliakoff M, Turner JJ. Analyst. 1994;119:551–560. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Towrie M, Grills DC, Dyer J, Weinstein JA, Matousek P, Barton R, Bailey PD, Subramaniam N, Kwok WM, Ma CS, et al. Appl Spectrosc. 2003;57:367–380. doi: 10.1366/00037020360625899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC. Gaussian 03. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian; 2004. Rev sC.02. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vosko SH, Wilk L, Nusair M. Can J Phys. 1980;58:1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee CT, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krishnan R, Binkley JS, Seeger R, Pople JA. J Chem Phys. 1980;72:650–654. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hay PJ, Wadt WR. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:270–283. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dunning TH, Jr, Hay PJ. In: Modern Theoretical Chemistry. Schaefer HF III, editor. Vol 3. New York: Plenum; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehlers AW, Bohme M, Dapprich S, Gobbi A, Hollwarth A, Jonas V, Kohler KF, Stegmann R, Veldkamp A, Frenking G. Chem Phys Lett. 1993;208:111–114. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.