Abstract

Forty-three percent (12/28) of ciprofloxacin (CIP)-nonsusceptible respiratory isolates of Haemophilus influenzae were hypermutable, compared with 8.5% (3/35) in the CIP-susceptible control group (P = 0.002). CIP-nonsusceptible mutants were obtained with hypermutable strains only; these mutants developed three resistance mechanisms in a step-by-step process: target modifications, loss of a porin protein, and increased efflux.

Fluoroquinolone-resistant Haemophilus influenzae isolates have been described in several countries (4, 5, 8, 17, 19). In general, hypermutable isolates contribute to the emergence of antibiotic resistance (3, 9). Fluoroquinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus is related to hypermutability (23). We and other authors have reported a high prevalence of hypermutable H. influenzae isolates causing respiratory infections (22, 24). We also noticed a high rate of fluoroquinolone resistance in these isolates (22) and reported a therapeutic failure in a community-acquired pneumonia case due to levofloxacin-resistant H. influenzae (2).

The main mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance in H. influenzae is amino acid changes in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of the topoisomerase II and I genes (5, 8, 9). Although not reported in H. influenzae, mutations resulting in overexpression of efflux pumps and permeability defects can also affect quinolone susceptibility (12).

In this study, we investigated the hypothesis that ciprofloxacin (CIP) resistance in H. influenzae occurs mainly in hypermutable clinical isolates. To test this hypothesis, first we made an observational study, and after that, we subjected CIP-susceptible hypermutable isolates to selective pressure with CIP. We also characterized other mechanisms of resistance in highly fluoroquinolone-resistant isogenic mutants as overexpression of efflux pumps and permeability defects.

The CIP reduced-susceptibility study group included 28 clinical isolates (3 from the United States [1] and 25 from Spain) chosen because they had amino acid changes in GyrA of the QRDR (21) and corresponding MICs for CIP of 0.12 to 32 μg/ml. The CIP-susceptible control group contained 35 clinical strains without amino acid changes and corresponding MICs for CIP of <0.12 μg/ml. All strains were noncapsulated and were isolated from respiratory specimens of adult patients with chronic respiratory infections (19, 21).

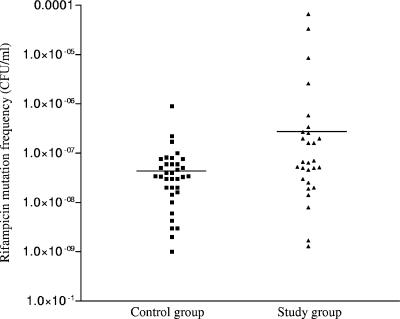

The study of mutation frequencies in response to rifampin was done in triplicate as described previously (22). Isolates were considered hypermutable if their mutation frequency was 10−7 CFU/ml or higher (22). Forty-three percent of the strains (12/28) in the study group were hypermutable, compared to 8.5% (3/35) in the control group (odds ratio, 8; P, 0.0024). The average mutation frequencies in the two groups (4 × 10−6 CFU/ml for the study group and 7 × 10−8 CFU/ml for the control group) differed significantly (P, 0.017; Mann-Whitney U test). The mutation frequency distributions are shown in Fig. 1. A positive correlation was found between mutation frequency and the MIC for CIP (Pearson coefficient = 0.34; P = 0.006).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of H. influenzae strains according to their mutation frequency in response to rifampin and according to the presence of amino acid changes in the quinolone resistance-determining region of GyrA. The control group comprises strains with no amino acid changes in the quinolone resistance-determining region of GyrA and MICs for CIP of <0.12 μg/ml. The study group comprises strains with amino acid changes in the quinolone resistance-determining region of GyrA and MICs for CIP of 0.12 μg/ml to 32 μg/ml. Horizontal bars represent the average mutation frequency of the study group (4 × 10−6 CFU/ml) and the control group (7 × 10−8 CFU/ml) (P = 0.017; Mann-Whitney U test).

We further subjected 12 susceptible clinical isolates of H. influenzae to in vitro selective pressure with CIP in a step-by-step procedure in Haemophilus test medium plates containing 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 10 μg/ml CIP. Six isolates were nonhypermutable, and the other six were hypermutable; all had MICs for CIP of <0.12 μg/ml and were without amino acid substitutions in GyrA or ParC. Three of the hypermutable fluoroquinolone-susceptible strains came from a previous study (22).

We obtained isogenic in vitro nonsusceptible mutants from only four hypermutable isolates (Table 1). Using overlapping primer sets (Table 2), we sequenced the mutS and mutL genes of these four hypermutable clinical isolates (named A to D), and representative CIP-nonsusceptible isogenic mutants identified as A1 to A4 (derived from strain A), B1 and B2 (from strain B), C1 to C3 (from strain C) and D1 to D4 (from strain D) (Table 1). As a control, we used a nonhypermutable and fluoroquinolone-susceptible clinical isolate. All sequences were compared with that of H. influenzae Rd KW20 (7). No amplifications were obtained with primers for the first mutS DNA fragment, possibly due to a deletion in the gene. No changes were identified in the mutS sequence, but all strains presented one common mutation (Asn589Asp) in mutL that did not appear in the nonhypermutable control strain.

TABLE 1.

Quinolone susceptibility, amino acid changes in GyrA and ParC quinolone resistance-determining regions, and changes detected in AcrR from Haemophilus influenzae isolatesa

| MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

Amino acid change(s)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | CIP | Levofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | Nalidixic acid | GyrA | ParC | AcrR (corresponding codon position) |

| Ab | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.50 | − | − | SC (97) |

| A1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.0 | Glu83Cys | Ser84Arg | SC (97) |

| A2 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 64 | Glu83Cys | Ser84Arg | SC (97) |

| A3 | 2.0 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 64 | Glu83Cys | Ser84Arg | SC (97) |

| A4 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 128 | Glu83Cys | Ser84Arg | SC (97) |

| Bb | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.50 | − | − | Leu31His |

| B1 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 32 | Asp88Tyr | − | Leu31His |

| B2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 64 | Asp88Tyr | − | Leu31His |

| Cb | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.50 | − | − | Leu31His Arg34Glu |

| C1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 16 | Asp88Asn | − | Leu31His Arg34Glu |

| C2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 128 | Asp88Asn | − | Leu31His Arg34Glu |

| C3 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 128 | Asp88Asn | Ser84Ile | Leu31His Arg34Glu |

| Db | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.50 | − | − | Leu31His Ile121Val Gln134Lys |

| D1 | 1.0 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 64 | Ser84Tyr | Glu88Lys | Leu31His Ile121Val Gln134Lys |

| D2 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 64 | Ser84Tyr | Glu88Lys | Leu31His Ile121Val Gln134Lys |

| D3 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 128 | Ser84Tyr | Glu88Lys | Leu31His Ile121Val Gln134Lys |

| D4 | 16 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 128 | Ser84Tyr | Glu88Lys | Leu31His Ile121Val Gln134Lys |

“Susceptible strains” have a MIC for CIP of <0.12 μg/ml and no amino acid changes in GyrA of the QRDR; “nonsusceptible strains” have a MIC range for CIP of 0.12 to 0.5 μg/ml and one mutation in GyrA of the QRDR; “resistant strains” have a MIC for CIP of >0.5 μg/ml and amino acid changes in GyrA and ParC of the QRDR (21). −, no amino acid changes detected in comparison with H. influenzae Rd DW20 (7); SC, corresponding stop codon.

Wild strain before exposure to antibiotic pressure.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of specific primers used for the sequencing of mutS and mutL in the present study

| Gene | Primera | Nucleotide sequence |

|---|---|---|

| mutS | Mut S F1 | 5′-AAGCAGGTCAAGACATCGCAA-3′ |

| Mut S R1 | 5′-CACACCAAAGGCACGTAAATC-3′ | |

| Mut S F2 | 5′-GCGGAATTGCAACGTATTGCA-3′ | |

| Mut S R2 | 5′-GCACTGCTCGCTGAAATC-3′ | |

| Mut S F3 | 5′-AGTCGGTGATATGGAGCGTAT-3′ | |

| Mut S R3 | 5′-GGTTGGCGATGAAAGGATCTT-3′ | |

| Mut S F4 | 5′-AGGCGCAGCGTTAGCATTAGA-3′ | |

| Mut S R4 | 5′-CCAAAGCCGCGACTGCCAAAC-3′ | |

| Mut S F5 | 5′-CTTAGCTTGGGCTTGTGCGGA-3′ | |

| Mut S R5 | 5′-CCACGACTGCAGTGTGACCAA-3′ | |

| mutL | Mut L F1 | 5′-ATGCTATTTCGAGGGAATATA-3′ |

| Mut L R1 | 5′-TAAAGCAATACGACGAATGAC-3′ | |

| Mut L F2 | 5′-AACTGAAGCGTGGCAAGTTTA-3′ | |

| Mut L R2 | 5′-ACCGCACTTTGGTCTGTATGC-3′ | |

| Mut L F3 | 5′-ACCCGCACGATGTAGATGTCA-3′ | |

| Mut L R3 | 5′-ATTCGGAACACGATTGGAATC-3′ | |

| Mut L F4 | 5′-GAGTGTTCATCACATCTACGA-3′ | |

| Mut L R4 | 5′-TTCGACTGGAAGTTGGCTTCG-3′ |

The DNA sequences of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE in the QRDR were determined in strains A, B, C, and D and in all isogenic CIP-resistant mutants, as described previously (21). CIP-nonsusceptible mutants also presented decreased susceptibility to other quinolones (Table 1). No mutations of GyrA or ParC in the QRDR were detected in wild isolate A, B, C, or D, but they were present in all mutants analyzed. All of these changes are involved in fluoroquinolone resistance (20, 25). No changes in GyrB and ParE of the QRDR were observed.

There was incomplete agreement between the level of resistance to fluoroquinolones and the number of amino acid changes identified. For instance, the four mutants derived from strain A had the same amino acid substitution pattern in GyrA and ParC although their MICs varied from 0.25 to 4 μg/ml (Table 1), suggesting that additional resistance mechanisms such as permeability and/or active efflux may be present.

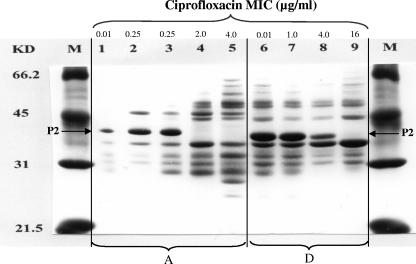

Profiles of outer membrane proteins were obtained as described previously (22) for wild strains A and D and their isogenic mutants. We observed the disappearance of the major ∼40-kDa P2 porin band (Fig. 2, lanes 4, 5, and 9), which has been shown to present a homology of 25% in the primary amino acid sequence with the OmpF porin of Escherichia coli (11), which is involved in CIP resistance (6).

FIG. 2.

Profile of outer membrane proteins in the H. influenzae wild strains A (lane 1) and D (lane 6) and their in vitro mutants A1, A2, A3, and A4 (lanes 2 to 5) and D1, D2, and D4 (lanes 7 to 9). Outer membrane protein porin P2 is indicated. KD and M, molecular mass markers in kDa.

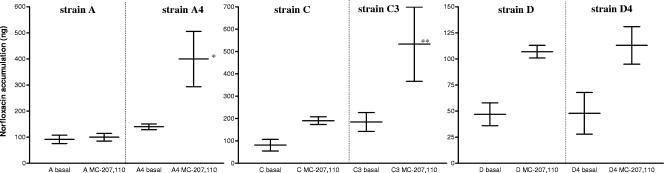

A potential active efflux mechanism of resistance was determined in triplicate by spectrophotometrically measuring the accumulation of CIP and norfloxacin in strains A and A4, C and C3, and D and D4. Bacterial cells were incubated with and without cyanide 3-chlorophenyl (CCCP; 0.1 mM) and Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (MC-207,110 compound; 0.1 mM) as efflux pump inhibitors (14, 15). By definition, a strain expressed energy-dependent accumulation when the pump inhibitor enhanced the basal level of accumulation by at least 50% (16).

We detected a significant increase in the accumulation of fluoroquinolones for the MC-207,110 compound, which was more evident for norfloxacin than for CIP. Norfloxacin accumulation increased by 2,126% (21 times) in the mutant strain C3 compared with strain C, and 140% (1.4 times) in the isogenic mutant A4 with respect to strain A. In the D/D4 strains, the increase exceeded 50% for D4 but an increase was also seen for the wild strain D (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Accumulation of norfloxacin in three pairs of isogenic strains in the absence (basal) and presence (0.1 mM) of MC-207,110. Vertical lines separate wild strains (A, C, and D) from their in vitro mutants (A4, C3, and D4). The data shown are the averages ± standard deviations of triplicate experiments. *, increase over basal accumulation of 2,126% (21 times); **, increase over basal accumulation of 140% (1.4 times).

Since an efflux mechanism appeared to be involved, we sequenced the acrR gene, which codes for a repressor of the AcrAB-ToldC homolog efflux pump in H. influenzae, in the four wild strains and in the CIP-nonsusceptible isogenic strains (13). However, the mutants and wild strains had identical acrR sequences (Table 1).

In this study, we have shown that hypermutability is a risk condition for the development of fluoroquinolone resistance in H. influenzae. Since hypermutable isolates are particularly frequent in chronic respiratory infections (22, 24), precautions are advised when treating these patients with fluoroquinolones. This study confirms that target modification is the first and most important mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance in H. influenzae; however, two new associated mechanisms, increased efflux and porin loss, also appear to be important in explaining increased levels of resistance to fluoroquinolones in this pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Biopolymers and Spongiform Encephalopathy units of the ISCIII.

S.G. is the recipient of a fellowship of the ISCIII (reference 05/0033). This work was supported by research grants from the ISCIII, REIPI Network (reference RD 06/0008/0023), the Network of Excellence GRACE (PL 518226), and “Fondó de Investigaciones cientificas” (FIS, PI 04/0899).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barriere, S. L., and J. Hindler. 1993. Ciprofloxacin resistant Haemophilus influenzae in a patient with chronic lung disease. Ann. Pharmacother. 27:309-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastida, T., M. Perez-Vazquez, J. Campos, M. C. Cortes-Lletget, F. Roman, F. Tubau, A. G. de la Campa, and C. Alonso-Tarres. 2003. Levofloxacin treatment failure in Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1475-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blázquez, J. 2003. Hypermutation as a factor contributing to the acquisition of antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1201-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bootsma, H. G., A. Troelstra, A. V. Veen-Rutgers, F. R Mooi, A. J. de Neeling, and B. P. Overbeek. 1997. Isolation and characterization of a ciprofloxacin-resistant isolate of Haemophilus influenzae from The Netherlands. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:292-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos, J., F. Román, M. Georgiou, C. García, R. Gómez-Lus, R. Cantón, H. Escobar, and F. Baquero. 1996. Long-term persistence of ciprofloxacin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 174:1345-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, S. P., L. M. McMurry, D. C. Hooper, J. S. Wolfson, and S. B. Levy. 1989. Cross-resistance to fluoroquinolones in multiple-antibiotic-resistant (Mar) Escherichia coli selected by tetracycline or chloramphenicol: decreased drug accumulation associated with membrane changes in addition to OmpF reduction. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:1318-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, J. M. Merrick, et al. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of H. influenzae Rd. Science 269:449-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgiou, M., R. Muñoz, F. Román, R. Cantón, R. Gómez-Lus, J. Campos, and A. G. De La Campa. 1996. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae strains possess mutations in analogous positions of GyrA and ParC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1741-1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giraud, A., I. Mastic, M. Radman, M. Fons, and F. Taddei. 2002. Mutator bacteria as a risk factor in treatment of infectious diseases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:863-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reference deleted.

- 11.Hansen, E. J., C. Hasemann, A. Clausell, J. D. Capra, K. Orth, C. R. Moomaw, C. A. Slaughter, J. L. Latimer, and E. Miller. 1989. Primary structure of the porin protein of Haemophilus influenzae type b determined by nucleotide sequence analysis. Infect. Immun. 57:1100-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooper, D. C. 2005. Efflux pumps and nosocomial antibiotic resistance: a primer for hospital epidemiologists. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1811-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaczmarek, F. S., T. D. Gootz, F. Dib-Hajj, W. Shang, S. Hallowell, and M. Cronan. 2004. Genetic and molecular characterization of β-lactamase-negative ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae with unusually high resistance to ampicillin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1630-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomovskaya, O., M. S. Warren, A. Lee, J. Galazzo, R. Fronko, M. Lee, J. Blais, D. Cho, S. Chamberland, T. Renau, R. Leger, S. Hecker, W. Watkins, K. Hoshino, H. Ishida, and V. J. Lee. 2001. Identification and characterization of inhibitors of multidrug resistance efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel agents for combination therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:105-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez-Martínez, L., I. García, S. Ballesta, V. J. Benedí, S. Hernández-Allés, and A. Pascual. 1998. Energy-dependent accumulation of fluorquinolones in quinolone-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1850-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez-Martínez, L., A. Pascual, M. C. Conejo, I. García, P. Joyanes, A. Doménech-Sánchez, and V. J. Benedí. 2002. Energy-dependent accumulation of norfloxacin and porin expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and relationship to extended-spectrum β-lactamase production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3926-3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazir, J., C. Urban, N. Mariano, J. Burns, B. Tommasulo, C. Rosenberg, S. Segal-Maurer, and J. J. Rahal. 2004. Quinolone-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in a long-term care facility: clinical and molecular epidemiology Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1564-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reference deleted.

- 19.Pérez-Vázquez, M., F. Román, M. C. Varela, R. Cantón, and J. Campos. 2003. Activities of thirteen quinolones by three susceptibility testing methods against a collection of Haemophilus influenzae isolates with different levels of susceptibility to ciprofloxacin: evidence for cross-resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez-Vázquez, M., F. Román, B. Aracil, R. Cantón, and J. Campos. 2003. In vitro activities of garenoxacin (BMS-284756) against Haemophilus influenzae isolates with different fluoroquinolone susceptibilities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3539-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez-Vázquez, M., F. Román, B. Aracil, R. Cantón, and J. Campos. 2004. Laboratory detection of Haemophilus influenzae with decreased susceptibility to nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin due to GyrA and ParC mutations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Román, F., R. Cantón, M. Pérez-Vázquez, F. Baquero, and J. Campos. 2004. Dynamics of long-term colonization of respiratory tract by Haemophilus influenzae in cystic fibrosis patients shows a marked increase in hypermutable strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1450-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trong, H. N., A.-L. Prunier, and R. Leclercq. 2005. Hypermutable and fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2098-2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson, M. E., Jr., J. L. Burns, and A. L. Smith. 2004. Hypermutable Haemophilus influenzae with mutations in mutS are found in cystic fibrosis sputum. Microbiology 150:2947-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida, H., M. Bogaki, M. Nakamura, and S. Nakamura. 1990. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1271-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]