Abstract

The activities of several tricyclic heteroaryl isothiazolones (HITZs) against an assortment of gram-positive and gram-negative clinical isolates were assessed. These compounds target bacterial DNA replication and were found to possess broad-spectrum activities especially against gram-positive strains, including antibiotic-resistant staphylococci and streptococci. These included methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-nonsusceptible staphylococci, and quinolone-resistant strains. The HITZs were more active than the comparator antimicrobials in most cases. For gram-negative bacteria, the tested compounds were less active against members of the family Enterobacteriaceae but showed exceptional potencies against Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Neisseria spp. Good activity against several anaerobes, as well as Legionella pneumophila and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, was also observed. Excellent bactericidal activity against staphylococci was observed in time-kill assays, with an approximately 3-log drop in the numbers of CFU/ml occurring after 4 h of exposure to compound. Postantibiotic effects (PAEs) of 2.0 and 1.7 h for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus and MRSA strains, respectively, were observed, and these were similar to those seen with moxifloxacin at 10× MIC. In vivo efficacy was demonstrated in murine infections by using sepsis and thigh infection models. The 50% protective doses were ≤1 mg/kg of body weight against S. aureus in the sepsis model, while decreases in the numbers of CFU per thigh equal to or greater than those detected in animals treated with a standard dose of vancomycin were seen in the animals with thigh infections. Pharmacokinetic analyses of treated mice indicated exposures similar to those to ciprofloxacin at equivalent dose levels. These promising initial data suggest further study on the use of the HITZs as antibacterial agents.

Antibiotic resistance is a significant problem worldwide and often results in limited treatment options for serious infections. Bacterial pathogens of current concern include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (PRSP), vancomycin-resistant enterococci, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing gram-negative organisms, and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8, 12, 15, 21). Staphylococci, particularly MRSA, but also coagulase-negative staphylococcal strains, have posed a challenge in hospital settings, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Vancomycin is often used to treat MRSA infections, but in recent years there have been reports of vancomycin-nonsusceptible isolates, with the first strains having intermediate resistance and then with fully resistant strains appearing (1, 3, 4, 11). In addition, community-associated MRSA isolates have now become more widespread, accounting for an increasing number of serious infections (5). Despite the growing unmet medical need, few new antibacterial agents that are effective against many of these often highly resistant clinical isolates have been introduced in recent years.

Serious resistance issues are now associated with all commonly used classes of clinical agents. β-Lactam resistance, mediated by modified penicillin-binding proteins in gram-positive bacteria and by numerous β-lactamase enzymes in both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, continues to erode the usefulness of this class (22). Efflux pumps can reduce the effectiveness of macrolides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and other drugs against many clinical strains (18, 19, 24). In addition to efflux, target modification by mutation affects such antibiotics as the fluoroquinolones, one of the more recent and widely used classes of compounds (13, 14). Even vancomycin, often a last option for the treatment of infections caused by gram-positive pathogens, eventually encountered resistance, as some strains have acquired altered cell wall compositions in order to survive exposure to the drug (8, 11). Although these and other antibacterial agents have been continuously modified and improved over the years with the synthesis of new analogs, clinical isolates resistant to these classes continue to present serious treatment challenges.

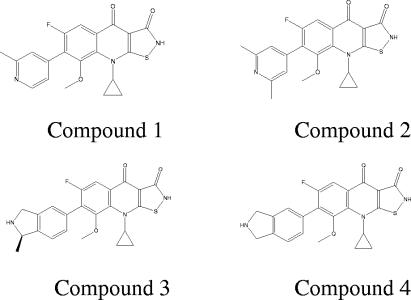

In this work, we discuss the antibacterial properties of a class of compounds, the heteroaryl isothiazolones (HITZs; representative structures are shown in Fig. 1), which display broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. These compounds target bacterial DNA replication and are potent inhibitors of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Earlier representatives from this class were described many years ago (6, 7) but apparently were not further developed as antibacterial drugs. We recently reported on the chemical synthesis and preliminary biological profiling of a number of new analogs within this class (26-28). The data presented here provide a more detailed summary of several of the antibacterial properties of these compounds. The in vitro activities of these compounds against a variety of recent clinical isolates, including strains resistant to other commonly used antibiotics, were determined. These compounds were found to be particularly active against gram-positive pathogens, including antibiotic-resistant organisms, such as MRSA. In addition, in vivo efficacy against staphylococci was demonstrated in two mouse models of infection: the sepsis and thigh infection models. These bactericidal compounds offer the potential for further development as effective new antibacterials, especially against gram-positive pathogens such as MRSA.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of the heteroaryl isothiazolones discussed in this work.

(This work was presented in part at the 46th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, CA [M. J. Pucci, C. Thoma, S. D. Podos, J. Cheng, J. A. Thanassi, Y. Ou, D. D. Buechter, G. Mushtaq, J. A. Vigliotti, B. J. Bradbury, and M. Deshpande, Abstr. 46th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F1-1997, 2006].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) strains were obtained from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance (NIH contract NO1-A1-95359). All other clinical isolates used (see Table 1) were from the strain collection at Focus Bio-Inova (now Eurofins), Herndon, VA. Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 13709, ATCC 29213, ATCC 700699 (strain Mu50), and ATCC 33591 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. S. aureus MRSA strains BSA643 and BSA678 were obtained from Donald Low, Department of Microbiology, Toronto Medical Laboratories, and Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (14).

TABLE 1.

Antibacterial activities of heteroaryl isothiazolones against selected bacterial strains

| Organism (no. of strains) and compound | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |

| MSSA (13) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.002-1 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| Compound 2 | 0.001-1 | 0.004 | 0.5 |

| Compound 3 | 0.008-2 | 0.008 | 1 |

| Compound 4 | 0.008-2 | 0.12 | 1 |

| Azithromycin | 0.5->8 | 1 | >8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12->16 | 0.25 | >16 |

| Linezolid | 2-2 | 2 | 2 |

| Oxacillin | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Vancomycin | 1-2 | 1 | 2 |

| MRSA (39) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.03-2 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Compound 2 | 0.001-2 | 0.12 | 1 |

| Compound 3 | 0.06->2 | 1 | 2 |

| Compound 4 | 0.004-2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Azithromycin | 0.5->8 | >8 | >8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12->16 | 16 | >16 |

| Linezolid | 0.5->16 | 2 | 2 |

| Oxacillin | 4->16 | >16 | >16 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5->32 | 1 | 8 |

| S. pneumoniae (31) | |||

| Compound 1 | <0.015-0.03 | <0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 2 | <0.015-0.06 | <0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 3 | <0.015-0.03 | <0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 4 | <0.015-<0.015 | <0.015 | <0.015 |

| Azithromycin | 0.03->8 | 4 | >8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-2 | 1 | 1 |

| Linezolid | 0.25-2 | 1 | 1 |

| Penicillin | ≤0.015-8 | 0.25 | 4 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.015-8 | 0.12 | 2 |

| Vancomycin | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Viridans group | |||

| streptococci (11) | |||

| Compound 1 | <0.015-0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Compound 2 | <0.015-0.03 | <0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 3 | <0.015-0.03 | <0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 4 | <0.015-<0.015 | <0.015 | <0.015 |

| Azithromycin | <0.008->8 | 1 | 4 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Linezolid | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Penicillin | 0.03-1 | 0.12 | 1 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06-2 | 0.12 | 1 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| A. baumannii (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.03->64 | 0.25 | 64 |

| Compound 2 | 0.06-64 | 0.5 | 64 |

| Compound 3 | 0.008-64 | 0.06 | 32 |

| Compound 4 | 0.008-32 | 0.03 | 32 |

| Ampicillin | 4->32 | 16 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.03->8 | 0.25 | >8 |

| Cefepime | 0.5->32 | 2 | 32 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.5->32 | 4 | >32 |

| Imipenem | 0.06->16 | 1 | >16 |

| Ceftriaxone | 4->64 | 8 | >64 |

| Enterobacter spp. (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.25-4 | 1 | 4 |

| Compound 2 | 0.25-8 | 1 | 4 |

| Compound 3 | 0.03-0.5 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| Compound 4 | 0.015-1 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| Ampicillin | 2->32 | >32 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.008-0.5 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| Cefepime | 0.03-32 | 0.06 | 4 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.06->32 | 0.5 | >32 |

| Imipenem | 0.5-4 | 1 | 2 |

| Ceftriaxone | <0.015->64 | 0.12 | >64 |

| E. coli (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.12-32 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| Compound 2 | 0.12-64 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Compound 3 | 0.03-4 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Compound 4 | 0.015-4 | 0.015 | 0.5 |

| Ampicillin | 2->32 | 4 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.015->8 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Cefepime | 0.015->32 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.06->32 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Ceftriaxone | <0.015->64 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| K. pneumoniae (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.25-16 | 1 | 8 |

| Compound 2 | 0.5-16 | 2 | 8 |

| Compound 3 | 0.03-2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Compound 4 | 0.015-4 | 0.015 | 0.5 |

| Ampicillin | 32->32 | >32 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.015-8 | 0.25 | 2 |

| Cefepime | 0.06->32 | 0.5 | 32 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25->32 | 32 | >32 |

| Imipenem | 0.5-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06->64 | 16 | 32 |

| Bacteroides fragilis (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.12-0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Clindamycin | 0.25-4 | 1 | 4 |

| Imipenem | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Penicillin | 0.5-32 | 16 | 16 |

| Clostridium difficile (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.25-4 | 0.25 | 2 |

| Clindamycin | 1->32 | 2 | >32 |

| Imipenem | 4-16 | 4 | 4 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Penicillin | 0.5-4 | 1 | 1 |

| E. faecalis (16) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.06-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Compound 2 | 0.06-2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Compound 3 | 0.06-2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Compound 4 | 1-16 | 4 | 8 |

| Azithromycin | 0.5->16 | 4 | >16 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5->16 | 16 | >16 |

| Linezolid | 0.5->16 | 2 | >16 |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 2->8 | 4 | >8 |

| Vancomycin | 1->32 | 2 | >32 |

| E. faecium (15) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.25-4 | 2 | 4 |

| Compound 2 | 1-8 | 2 | 8 |

| Compound 3 | 0.5-8 | 4 | 8 |

| Compound 4 | 1-16 | 4 | 8 |

| Azithromycin | 2->16 | >16 | >16 |

| Levofloxacin | 4->16 | >16 | >16 |

| Linezolid | 0.5->16 | 2 | 2 |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vancomycin | 1->32 | >32 | >32 |

| S. pyogenes (20) | |||

| Compound 1 | <0.015-0.03 | <0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 2 | <0.015-0.03 | <0.015 | <0.015 |

| Compound 3 | <0.015-0.03 | <0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 4 | <0.015-<0.015 | <0.015 | <0.015 |

| Azithromycin | 0.03->8 | 0.12 | >8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Linezolid | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Penicillin | ≤0.015-0.12 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.015-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| L. pneumophila (1) | |||

| Compound 1 | ≤0.004 | ||

| Azithromycin | 0.12 | ||

| Doxycycline | 1 | ||

| Levofloxacin | 0.015 | ||

| M. pneumoniae (1) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.12 | ||

| Azithromycin | ≤0.004 | ||

| Doxycycline | 0.25 | ||

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | ||

| P. aeruginosa (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 2->64 | 4 | 64 |

| Compound 2 | 2->64 | 4 | >64 |

| Compound 3 | 0.5->64 | 1 | 64 |

| Compound 4 | 0.25->64 | 1 | 64 |

| Ampicillin | >32->32 | >32 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.12->8 | 0.5 | >8 |

| Cefepime | 1->32 | 2 | 16 |

| Ceftazidime | 2->32 | 2 | 32 |

| Imipenem | 1-16 | 2 | 4 |

| Ceftriaxone | 32->64 | 64 | >64 |

| H. influenzae (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | <0.008-0.03 | 0.015 | 0.03 |

| Compound 2 | <0.008-0.06 | 0.015 | 0.06 |

| Compound 3 | <0.008-0.03 | <0.008 | 0.015 |

| Compound 4 | <0.008-0.015 | <0.008 | <0.008 |

| Azithromycin | 0.25-2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.008-0.03 | 0.015 | 0.03 |

| Ampicillin | 0.06->16 | >16 | >16 |

| Ceftriaxone | <0.008-0.015 | <0.008 | 0.015 |

| M. catarrhalis (13) | |||

| Compound 1 | <0.008-0.015 | <0.008 | <0.008 |

| Compound 2 | <0.008-0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 |

| Compound 3 | <0.008-0.03 | 0.015 | 0.015 |

| Compound 4 | <0.008-0.015 | <0.008 | 0.015 |

| Azithromycin | 0.015-0.03 | 0.015 | 0.03 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Ampicillin | 1-16 | 4 | 8 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.015-2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| N. gonorrhoeae (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | ≤0.002-0.015 | ≤0.002 | 0.004 |

| Azithromycin | ≤0.03-0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.002-0.03 | 0.004 | 0.03 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.002-0.06 | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| Penicillin | ≤0.03-1 | 0.12 | 1 |

| Tetracycline | 0.12-1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| N. meningitidis (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | ≤0.002-≤0.002 | ≤0.002 | ≤0.002 |

| Azithromycin | 0.12-2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Meropenem | 0.008-0.03 | 0.008 | 0.015 |

| Levofloxacin | ≤0.12-≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 |

| Penicillin | ≤0.03-0.12 | ≤0.03 | 0.06 |

| Minocycline | 0.06-0.25 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Propionibacterium acnes (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.03-0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.03-0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Imipenem | 0.03-0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Metronidazole | >64->64 | >64 | >64 |

| Penicillin | ≤0.12-≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 |

| Peptostreptococcus species (10) | |||

| Compound 1 | 0.015-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Clindamycin | 0.12-4 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Imipenem | 0.03-0.5 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

In vitro susceptibility testing.

All susceptibility testing was done in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton II broth (CAMHB) (the media were obtained from BD, Sparks, MD, unless indicated otherwise). Streptococci were supplemented with 2 to 5% lysed horse blood, and Haemophilus influenzae was tested in Haemophilus test medium. Aerobic isolates were tested by broth microdilution by using the CLSI (formerly the NCCLS) defined methodology (16) with final inoculum sizes of approximately 5 × 105 CFU/ml for most strains. Inoculated plates were incubated aerobically at 35 to 37°C for 24 h, and the MIC was defined as the minimum concentration of compound that resulted in no visible growth after 24 h at 35 to 37°C. Anaerobic organisms were tested by agar dilution, as recommended by the CLSI (17), by using brucella agar supplemented with 5 mg/ml hemin, 1 mg/ml vitamin K, and 5% laked sheep blood. Inocula consisted of colonies taken from a 24-h growth on enriched blood agar and resuspended to approximate the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard in brucella broth. The plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions at 35 to 37°C for 48 h. Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates were grown 7 to 10 days in SP-4 broth (Mycoplasma broth base, tryptone, peptone, arginine, phenol red [1%], DNA) with glucose (pH 7.4) and diluted to the appropriate number of color-changing units [CCU]/ml [25]), with a final inoculum of approximately 104 CCU/ml. Incubation was at 35°C for 10 to 14 days. The MIC was defined as the lowest dilution of compound that inhibited growth, as indicated by a lack of color change relative to the color of the growth control (23, 25). Legionella pneumophila was tested by resuspending the colonies from 3- to 4-day-old buffered yeast extract agar to the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard and using approximately 5 × 105 CFU/ml as a final inoculum size. Incubation was for 48 h at 35 to 37°C.

The effects of changes of pH of the medium on the MICs of selected HITZs were determined in CAMHB. The pH of the broth was adjusted with 1.2 N HCl or 2.0 N NaOH to provide pHs that ranged from 5.0 to 9.0 (10). To determine the effects of the inoculum size on the MICs, CAMHB was inoculated with the test organism (S. aureus ATCC 700699) at final concentrations of 5 × 105 to 5 × 107 CFU/ml.

Time-kill studies.

S. aureus ATCC 700699 (strain Mu50) was cultured overnight at 37°C in CAMHB. Cells were diluted in medium to match the turbidity of the 0.5 McFarland standard and incubated with shaking at 35°C to achieve logarithmic growth phase. The culture was then diluted in medium to adjust the cell density to approximately 107 CFU/ml. Compounds were then added to final concentrations of 2, 4, 8, or 16 times the MIC. Rates of killing were determined by measuring the reduction in viable bacteria (log10 CFU/ml) at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h with fixed concentrations of compound (2). Experiments were performed in duplicate. If plates contained less than 10 CFU/ml, the number of colonies was considered to be below the limit of quantitation. Samples of culture containing compound were diluted at least 10-fold to minimize drug carryover to the CAMHB plates.

PAEs.

The postantibiotic effect (PAE) was determined following treatment of S. aureus with compound at 10× MIC for 1 h (9). Prewarmed 10-ml CAMHB cultures with or without antibiotic were inoculated with approximately 2 × 107 to 4 × 107 CFU/ml S. aureus ATCC 29213 or ATCC 700699 (strain Mu50) in logarithmic growth phase and were then grown with shaking at 35°C to 37°C for 1 h. After this exposure period, the cultures were diluted 1:1,000 in prewarmed CAMHB to initiate recovery. Viable counts were measured prior to exposure, immediately after dilution, and hourly for 4 to 8 h of recovery by plating appropriate dilutions onto CAMHB agar. An additional control with untreated bacteria was diluted into medium plus compound at 0.01× MIC to establish that residual compound during recovery had no effect on growth and viability (data not shown). The PAE was defined as T − C, where T is the time required for viability counts of an antibiotic-exposed culture to increase by 1 log10 above the counts present immediately after dilution, and C is the corresponding time for the growth control without antibiotic (20).

In vivo efficacy against experimental infections. (i) Mouse protection assay.

Adult female CD-1 mice (weight range, 20 to 29 g; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were inoculated intraperitoneally with a sufficient number of pathogens to kill 100% of the untreated animals within 5 days. Each mouse received ∼3.9 × 107 CFU/ml of S. aureus ATCC 13709 suspended in 5% (wt/vol) sterile hog gastric mucin in a volume of 0.5 ml. Test articles were administered subcutaneously at 1 h after pathogen inoculation. The number of mice that survived in each experimental group was monitored for up to 5 days after pathogen inoculation, and the 50% protective doses for the drug-treated animals were determined. Each experimental group consisted of six animals, and a minimum of four different concentrations of compound was evaluated. The ranges of doses were 0.625 to 10 mg/kg of body weight/day.

(ii) Mouse thigh muscle infection.

Adult female CD-1 mice (weight range, 19 to 28 g; Charles River Laboratories) were made neutropenic with two intraperitoneal injections of cyclophosphamide (150 mg/kg in 10 ml/kg; Sigma) at 4 days and 1 day before infection. Groups of three mice each were infected intramuscularly with approximately 105 CFU of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) ATCC 13709 or MRSA ATCC 33591 and were treated with either a single subcutaneous dose or an intravenous dose of compound at 2 h postinfection. Vancomycin was administered as a single subcutaneous dose. A control group of animals was not treated. Thighs from three animals were harvested at 2, 4, 6, or 24 h after treatment initiation. The thighs were processed by aseptic removal from each animal, dilution in sterile phosphate-buffered saline, and homogenization with a tissue homogenizer. Serial dilutions of the tissue homogenates were spread on Trypticase soy agar (BD) plates, and the plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. The numbers of CFU per thigh were determined from the colony counts and were compared with the numbers of CFU per thigh in the controls at the time of treatment.

Pharmacokinetics in mice.

The compounds were administered to fasted mice as single subcutaneous doses of 20 or 50 mg/kg. Blood samples were collected from groups of three mice each at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h after dosing. After the samples were processed, plasma samples were stored at −70°C prior to analysis. Plasma samples were analyzed by a tandem liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method on a Finnigan LCQ Deca Plus Ion Trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA). Briefly, after each sample was thawed on ice, the sample was protein precipitated with 2 volumes of cold acetonitrile containing the internal standard. The quenched samples were allowed to sit at room temperature for 15 min and were then centrifuged at 2,700 rpm for 5 min. Aliquots of the supernatants were chromatographed on a C8 Phenomenex Luna column (2.0 by 50 mm; 5-μm particle size). Mobile phase A was water with 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B was acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid; the flow rate was 0.4 ml/min. The method consisted of a gradient from 95% mobile phase A to 95% mobile phase B over 5 min. Peaks were detected by selected reaction monitoring at the respective mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) of each compound and internal standard in the positive electron spray ionization mode with an isolation width of 2. Quantitation was done by comparison of the compound peak areas of the plasma samples to those obtained from calibration samples prepared by spiking stock solutions of each compound into blank mouse plasma. Linear curve fits were generated from the calibrated data with Xcalibur QuanBrowser software (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA), version 1.4 SR1, with 1/x2 weighting. Calibration curves ranged from 5 to 15,000 ng/ml. The resulting mean plasma concentrations were analyzed by noncompartmental methods with WinNonlin software (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). The area under the concentration-versus-time curve (AUC) from time zero to the time of the last quantifiable plasma concentration was calculated by using the linear trapezoidal rule. The plasma half-life (t1/2) and the time at which the maximum concentration (Cmax) occurred after dosing (Tmax) were calculated with WinNonlin software.

RESULTS

Compound activities against clinical isolates.

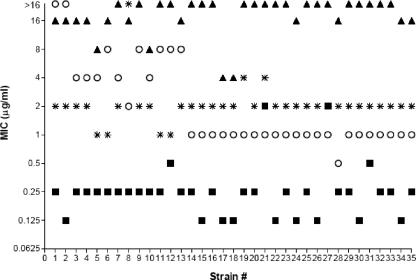

Table 1 compares the activities of heteroaryl isothiazolone compounds 1, 2, 3, and 4 (Fig. 1) against gram-positive clinical isolates to those of the comparator drugs. Against methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) strains, compounds 1 and 2 had potent MIC50s of 0.12 and 0.004 μg/ml, respectively, and MIC90s of 0.5 μg/ml. For MRSA strains, the antibacterial activity of compound 1 was particularly good, with an MIC50 of 0.25 μg/ml and an MIC90 of 0.5 μg/ml, while most of the comparator agents were essentially ineffective against these strains. The MIC90s of all currently marketed fluoroquinolones for quinolone-resistant MRSA are >4 μg/ml (2). Figure 2 further illustrates the improved activities of compounds 1 and 2 by showing the distribution of MICs compared with those of levofloxacin, vancomycin, and linezolid. These data also demonstrate that while the vast majority of current MRSA clinical isolates are fluoroquinolone resistant, compound 1 remained very active, with MICs 0.25 μg/ml and below against most of the strains in this panel. Against those MRSA strains with reduced vancomycin susceptibility, including both intermediate-resistant (VISA) and -resistant (VRSA) strains, compounds 1 and 2 retained activities nearly equivalent to those against vancomycin-susceptible strains (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Antibiotic resistance profiles of MRSA clinical isolates. Individual MRSA strains from Table 1 are plotted against the MICs (in μg/ml). Antibiotics: compound 1, ▪; levofloxacin, ▴; vancomycin, ○; linezolid, *.

The MIC50s and MIC90s of all four compounds for S. pneumoniae (31 total strains; Table 1), including penicillin-resistant isolates (11 strains), were excellent, with no significant differences in the MIC50s and MIC90s for penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae strains (14 strains), penicillin-intermediate strains (6 strains), and penicillin-resistant strains (PRSP; 11 strains) observed (data not shown). The MICs for penicillin-intermediate and PRSP strains were in the same range as those seen with penicillin and ceftriaxone for penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae strains (MICs, ≤0.015 to 0.06 μg/ml). Against enterococcal strains, compounds 2 and 3 had MIC50s and MIC90s of 0.5 and 1 μg/ml, respectively, for Enterococcus faecalis. These values were lower than those for all comparators tested with E. faecalis. However, the activities of all four compounds against Enterococcus faecium were limited, with MIC50s of 2 to 4 μg/ml and MIC90s of 4 to 8 μg/ml. Against additional streptococci, Streptococcus pyogenes, and viridans group streptococci, all four compounds were also quite active, with all MIC50s and MIC90s being ≤0.03 μg/ml.

Table 1 also compares the activities of compounds 1, 2, 3, and 4 against gram-negative clinical isolates to those of several comparator drugs. Although the activities were not as impressive as those observed against gram-positive strains, compounds 3 and 4 displayed relatively good activities against three species of the family Enterobacteriaceae tested, including Enterobacter spp., Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Against a limited number of strains, MIC90s were 0.5 μg/ml or less for most of the isolates. The MIC90s for all four compounds rose to 32 to >64 μg/ml for P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii; however, the MIC50s remained at 0.5 μg/ml or less for A. baumannii, suggesting good activity against some current clinical isolates. For Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, all compounds were quite active, with MIC90s ranging from <0.008 to 0.06 μg/ml, including for ampicillin-resistant strains. These MICs were equivalent or superior to those of all of the comparator compounds tested. In addition, compound 1 was tested against both Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis. Excellent activities against these organisms were observed, with MICs often less than the lowest concentration tested, 0.003 μg/ml.

The MICs of compound 1 for four anaerobes (Bacillus fragilis, Clostridium difficile, Propionibacterium acnes, and Peptostreptococcus species) are listed in Table 1. Against B. fragilis, compound 1 had MICs of 0.12 μg/ml for all 10 strains tested. These values are slightly less than those for imipenem and much improved compared with those for penicillin, clindamycin, and metronidazole. For C. difficile, 7 of 10 strains had MICs of 0.25 μg/ml, while the remaining 3 strains had MICs that ranged from 2 to 4 μg/ml. These were favorable results compared with those for the same four antibiotics mentioned above. Compound 1 was exceptionally active against Legionella pneumophila, with MICs of ≤0.004 μg/ml for all 10 clinical isolates tested (Table 1). The compound was also effective against Mycoplasma pneumoniae, with MICs of 0.12 μg/ml against all 10 strains tested; these results are comparable to those for doxycycline and levofloxacin, but compound 1 was less active than azithromycin against this pathogen (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the MICs of compounds 1, 2, and 4 against two MRSA clinical isolates, ATCC 700699 (strain Mu50) and BSA643, with probable enhanced efflux activity, as indicated by their elevated ethidium bromide MICs (24), in addition to topoisomerase target mutations. Another clinical isolate, isolate BSA678, has an ethidium bromide MIC of 4 μg/ml, similar to the levels seen with laboratory strains such as ATCC 29213. As illustrated here, no correlation of the antibacterial activities against MRSA strains with or without elevated ethidium bromide MICs was observed (see the results for BSA643 versus those for BSA678). Also, the presence of the efflux pump inhibitor reserpine (18) did not affect the S. aureus MICs obtained with the heteroaryl isothiazolones (Table 2). The ciprofloxacin MICs against ATCC 700699 remained 64 μg/ml in the presence or absence of reserpine, possibly indicating additional efflux beyond that mediated by the NorA pump. These data suggest that the antibacterial activity is minimally affected by the action of efflux pumps in staphylococci.

TABLE 2.

MICs of heteroaryl isothiazolones and selected quinolones against ethidium bromide-resistant strains

| Compound | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | S. aureus ATCC 29213 + reserpinea | S. aureus ATCC 700699 | S. aureus ATCC 700699 + reserpinea | S. aureus BSA643 | S. aureus BSA678 | |

| Compound 1 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Compound 2 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Compound 4 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 32 | 32 | 128 | >64 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06 | NDb | 4 | ND | 16 | >64 |

| Gemifloxacin | 0.03 | ND | 4 | ND | 32 | 64 |

| Ethidium bromide | 4 | 0.03 | 64 | 64 | 16 | 4 |

Final concentration, 20 μg/ml.

ND, not determined.

Bactericidal activity.

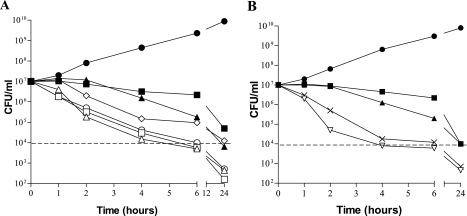

Bactericidal activity was assessed by using S. aureus as a model organism. Figure 3A shows representative time-kill curves for compound 1 against a quinolone-resistant MRSA strain, ATCC 700699, with vancomycin and gemifloxacin used as comparator drugs. Maximum killing was observed at concentrations of 4× MIC and higher, with a 3-log drop in the numbers of CFU/ml occurring by 4 h after compound addition. Killing was less rapid with 4× MICs of gemifloxacin and vancomycin than with compound 1 against the same strain. Killing was also less rapid at 2× MIC of compound 1, with which more than 6 h was required to effect a 3-log drop in the numbers of CFU/ml, suggesting a dose-dependent effect on staphylococcal killing up to a concentration equal to 4× MIC. Figure 3B shows similar rates of killing by two additional HITZs, compounds 2 and 4, at 4× MICs against ATCC 700699, again, with a 3-log drop in the numbers of CFU/ml after about 4 h of exposure. The HITZs were also observed to have bactericidal activity against E. coli, demonstrating that they rapidly kill both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Time-kill curves with MRSA strain ATCC 700699. (A) Bactericidal activity of compound 1 versus those of the comparator drugs at multiples of the MIC; (B) bactericidal activities of compounds 2 and 4 versus those of the comparator drugs at 4× MIC. Dotted lines indicate the numbers of CFU/ml for 3-log bacterial killing. Symbols: (A) •, growth control; ⋄, compound 1, 2× MIC; ▵, compound 1, 4× MIC; □, compound 1, 8× MIC; ○, compound 1, 16× MIC; ▴, gemifloxacin, 4× MIC; ▪, vancomycin, 4× MIC; (B) •, growth control; ▿, compound 2, 4× MIC; ×, compound 4, 4× MIC; ▴, gemifloxacin, 4× MIC; ▪, vancomycin, 4× MIC.

Effects of inoculum size and pH on in vitro susceptibility.

The activities of four heteroaryl isothiazolones against S. aureus were not affected by a 10-fold increase in the size of the bacterial inoculum to 5 × 106 CFU/ml (data not shown). However, when the inoculum was increased 100-fold to 5 × 107 CFU/ml, the MICs increased 2- to 4-fold (data not shown). The antibacterial activities of the HITZs were also determined in growth medium at different pHs. The compounds were more active against S. aureus ATCC 700699 at acidic or neutral pH (compound 2 MIC at pH 7, 1 μg/ml) than they were in basic medium (compound 2 MIC at pH 9, 32 μg/ml). A growth medium pH-to-MIC relationship was also observed with the fluoroquinolones ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin (data not shown). However, in contrast, these compounds were less active at acidic pH (moxifloxacin MIC of 64 μg/ml and ciprofloxacin MIC of >64 μg/ml at pH 5), similar to previously reported results (10).

PAEs.

The PAE is a measure of the effects of an antibiotic on the cellular viability of bacteria after exposure to that antibiotic is terminated. The PAEs of compound 1 and moxifloxacin were assessed with two S. aureus strains by measuring the time required for recovery after a defined treatment period (9). For MSSA strain ATCC 29213, the PAE for compound 1 was 2.0 ± 0.4 h, whereas the PAE was 1.6 ± 0.1 h for the comparator fluoroquinolone, moxifloxacin. For MRSA strain ATCC 700699, compound 1 had a PAE of 1.8 ± 0.4 h, which was similar to the PAE of 1.5 ± 0.4 h observed for moxifloxacin. These values were the averages of two independent experiments.

Therapeutic efficacy and pharmacokinetics in mice.

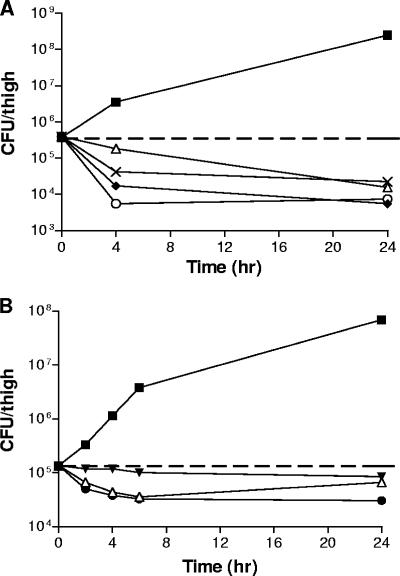

Therapeutic efficacy was demonstrated in a mouse thigh infection model. The S. aureus ATCC 13709 (MSSA) inoculum concentration was 1.14 × 106 CFU/ml, with 0.1 ml injected per thigh. The mean density of bacteria in control thighs at 2 h postinfection (the time of antibiotic treatment) was 2.77 × 105 CFU/ml. The control numbers of CFU/ml increased over 2.8 log units by 24 h after antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4). Subcutaneous treatment with vancomycin at 10 mg/kg resulted in reductions in the bacterial populations compared to those in the 2-h control of 0.31 and 1.37 log units 4 and 24 h after antibiotic treatment, respectively. Intravenous administration of compounds 2 and 4 at 20 mg/kg reduced the bacterial populations 1.34 and 2.13 log units, respectively, at 4 h after antibiotic treatment and 1.83 and 1.70 logs, respectively, at 24 h. The S. aureus ATCC 33591 (MRSA) inoculum concentration was 1.63 × 106 CFU/ml, with 0.1 ml injected per thigh. The mean density of bacteria in the control thighs at 2 h postinfection (the time of antibiotic treatment) was 1.39 × 105 CFU/ml. The control CFU/ml increased over 2.5 log units by 24 h after antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4B). Subcutaneous treatment with vancomycin at 10 mg/kg resulted in reductions in bacterial populations compared to those for the 0-h control of 0.32, 0.49, and 0.58 log units at 4, 6, and 8 h after antibiotic treatment, respectively. At 24 h after antibiotic treatment, the reduction was 0.31 log unit. As expected, subcutaneous treatment with linezolid at 20 mg/kg resulted in only slight drops in the numbers of CFU/ml of 0.05 to 0.20 log units. The subcutaneous administration of compound 1 at 20 mg/kg reduced the bacterial populations by a range of from 0.43 log unit at 4 h after infection to 0.66 log unit at 24 h. Similar results were observed when the compounds were administered by subcutaneous or intravenous injection (data not shown). Efficacy was also observed in a mouse sepsis model by using S. aureus ATCC 13709, with 50% protective doses of 1.0 and 0.7 mg/kg for compounds 1 and 2, respectively, after the administration of a single subcutaneous dose (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Therapeutic efficacies of HITZs and comparator drugs in a mouse thigh model of infection. The compounds were dosed 2 h postinfection, which is time zero on the plots. The numbers of CFU per thigh were determined at the indicated time points. (A) Infection with MSSA strain ATCC 13709. Symbols: untreated control, ▪; vancomycin at 10 mg/kg (subcutaneous), ▵; ciprofloxacin at 20 mg/kg (subcutaneous), ×; compound 2 at 20 mg/kg (intravenous), ♦; compound 4 at 20 mg/kg (intravenous), ○. (B) Infection with MRSA strain ATCC 33591. All compounds were administered as a single subcutaneous dose. Symbols: untreated control, ▪; linezolid at 20 mg/kg, ▾; vancomycin at 10 mg/kg, ▵; compound 1 at 20 mg/kg, •.

The values of the pharmacokinetic parameters for three heteroaryl isothiazolones in the plasma of treated mice were determined (Table 3). Mice were given a single subcutaneous dose. At 20 mg/kg, the AUC from time zero to 24 h (AUC0-24) for compounds 1, 2, and 4 and ciprofloxacin were 3.21, 3.34, 2.72, and 5.95 μg·h/ml, respectively. The range of Cmax values was 1.49 to 4.15 μg/ml. When the dose was increased to 50 mg/kg, the AUC0-24 and the Cmax values were 10.18 μg·h/ml and 10.55 μg/ml, respectively, for compound 1 and 14.43 μg·h/ml and 7.72 μg/ml, respectively, for ciprofloxacin. From these data, the HITZs showed similar or slightly lower exposure values than ciprofloxacin in mice, with compound 1 having the highest Cmax and AUC values among the three compounds tested.

TABLE 3.

Values of pharmacokinetic parameters in serum after administration of a single subcutaneous dose to mice

| Drug | Dose (mg/kg) | Cmax (μg/ml) | AUC (μg·h/ml) | t1/2 (h) | Tmax (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 1 | 20 | 4.15 | 3.21 | 2.12 | 0.25 |

| Compound 1 | 50 | 10.55 | 10.18 | 4.00 | 0.25 |

| Compound 2 | 20 | 2.20 | 3.34 | 3.54 | 0.08 |

| Compound 3 | 20 | 1.49 | 2.72 | 4.13 | 0.50 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 20 | 3.36 | 5.95 | 1.07 | 0.50 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 50 | 7.72 | 14.43 | 1.17 | 0.50 |

| Linezolid | 20 | 12.19 | 29.09 | 1.17 | 0.50 |

| Linezolid | 50 | 25.52 | 112.02 | 2.18 | 1.00 |

DISCUSSION

Initial studies showed that members of the HITZ compound class possessed in vitro activities against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, with particular effectiveness against gram-positive strains, including several antibiotic-resistant organisms, such as VISA, VRSA, and quinolone-resistant organisms. The MICs against gram-positive bacteria were generally superior to those of the comparator drugs tested, including vancomycin, linezolid, and levofloxacin (Fig. 2). Of note, there appeared to be some cross-resistance with quinolones, in that for the quinolone-susceptible staphylococcal isolates, which comprised 9 of the 13 MSSA strains tested in this work, the HITZ MICs were generally <0.008 μg/ml, while the MICs for quinolone-resistant strains (37 of the 39 MRSA strains) were 0.12 to 2 μg/ml. In comparison, the MICs of quinolones are often >16 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin- and levofloxacin-resistant MRSA strains. Some cross-resistance is not unexpected, since we believe that HITZs share antibacterial targets with the quinolone class. In addition, the MICs remained low against ethidium bromide-resistant staphylococcal strains and were unchanged in the presence of reserpine, suggesting that these HITZs, unlike some fluoroquinolones, were minimally affected by efflux in staphylococci (Table 2). Good activity was also observed against Haemophilus, Moraxella, and Neisseria, strains as well as against anaerobes, Legionella, and Mycoplasma clinical isolates, while activity against other gram-negative organisms, although more limited, was still evident. The most resistant gram-negative isolates, which comprise those with increased efflux plus high-level quinolone resistance, especially P. aeruginosa strains, were not susceptible to the HITZ compounds tested in this work. The reason for the exceptional activity against gram-positive organisms appears to be potent inhibition of both topoisomerase IV and gyrase targets, particularly the latter enzyme, including those from quinolone-resistant strains. Work is in progress to further validate this hypothesis (J. Cheng, J. A. Thanassi, C. L. Thoma, Y. Ou, B. A. Bradbury, M. Deshpande, and M. J. Pucci, unpublished data).

Similar to other classes of antibiotics, including the quinolones, the HITZs were found to be rapidly bactericidal against representative gram-positive bacteria (staphylococci; Fig. 3) and gram-negative bacteria (E. coli; data not shown), which is a desirable feature for the treatment of an infection caused by a serious pathogen. At concentrations greater than 4× MIC, no further increases in the rates of killing were observed. This suggests that killing at higher dose levels is concentration independent and could have pharmacodynamic implications. Compound 1 seemed especially bactericidal, displaying higher levels of killing than those displayed by both gemifloxacin and vancomycin at earlier times of exposure. These compounds also demonstrated a significant PAE, as shown by using S. aureus as a test organism, with values in the same range as those seen with moxifloxacin. This is another potential advantageous property during treatment of infections, as it can possibly enhance the effective exposure of drug in a patient and thus contribute to successful outcomes.

The therapeutic efficacies of two HITZs was demonstrated in both mouse sepsis and thigh infection models by using immunocompromised animals (Fig. 4). By using either MSSA or an MRSA as the infecting strain, the decreases in the numbers of CFU per thigh were either equivalent to or greater than those seen with vancomycin treatment. We believe that the effectiveness of these compounds is likely due to a combination of low MICs and relatively good pharmacokinetic parameter values in mice in the range of those seen with ciprofloxacin (Table 3). These experiments were done with single subcutaneous doses, and improved results might be possible with multiple doses to compensate for the relatively short half-lives in rodents. However, if the values of the pharmacokinetic parameters continue to track with those of ciprofloxacin, there is a reasonable expectation that half-lives and exposures will improve in other mammalian species and, it is hoped, can be extended to humans. We anticipate that the ratio of the AUC to the MIC will be the most important pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic driver, as is the case with fluoroquinolones, but this remains to be determined. Additional animal efficacy and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies are in progress.

In summary, the heteroaryl isothiazolones appear to possess excellent activities against gram-positive organisms, including MRSA strains, by both in vitro and in vivo assays. In addition, activities against gram-negative organisms are associated with these compounds, and it may be possible to find future derivatives that display improved potencies against the more challenging gram-negative pathogens. The compounds also displayed good bactericidal activities, along with good postantibiotic effects, and pharmacokinetic analyses revealed exposures similar to those for ciprofloxacin in mice. These compounds appear to be effective for the treatment of infections in animal, as efficacy against staphylococci was observed in both a murine sepsis model and a murine thigh infection model with immunocompromised mice. Together, these results indicate that the HITZs merit further characterization and may have the potential to advance into clinical development.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Akihiro Hashimoto, Edlaine Lucien, Yongsheng Song, Qiuping Wang, and Jason Wiles for synthetic chemistry efforts and Crit Marlor for computational assistance. We thank Focus Bio-Inova, especially Parveen Grover and Nina Brown, for MIC testing of the compounds. We acknowledge Ann O'Leary and her colleagues at Ricerca for running the mouse infection studies and Bill Brubaker for coordination of pharmacokinetic studies at FarmingtonPharma. We also thank Donald Low and Darrin Bast for supplying the MRSA clinical isolates. We are grateful to Junius Clark and Dan Sahm for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelbaum, P. C. 2006. The emergence of vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12(Suppl. 1):16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogdanovich, T., D. Esel, L. M. Kelley, B. Bozdogan, K. Credito, G. Lin, K. Smith, L. M. Ednie, D. B. Hoellman, and P. Appelbaum. 2005. Antistaphylococcal activity of DX-619, a new des-F(6)-quinolone, compared to those of other agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:325-3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1997. Update: Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin—United States, 1997. JAMA 278:1145-1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Pennsylvania, 2002. JAMA 288:2116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers, H. F. 2005. Community-associated MRSA—resistance and virulence converge. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:1485-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu, D. T., P. B. Fernandes, A. K. Claiborne, L. Shen, and A. G. Pernet. 1988. Structure-activity relationships in quinolone antibacterials: design, synthesis, and biological activities of novel isothiazoloquinolones. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 14:379-383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu, D. T., I. M. Lico, A. K. Claiborne, J. J. Plattner, and A. G. Pernet. 1990. Structure-activity relationship of quinolone antibacterial agents: the effects of C-2 substitution. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 16:215-224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courvalin, P. 2006. Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl. 1):S25-S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig, W. A., and S. Gudmundsson. 1996. Postantibiotic effect, p. 296-329. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, MD.

- 10.Gudmundsson, A., H. Erlendsdottir, M. Gottfredsson, and S. Gudmundsson. 1991. Impact of pH and cationic supplementation on in vitro postantibiotic effect. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:2617-2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiramatsu, K., H. Hanaki, T. Ino, K. Yabuta, T. Oguri, and F. C. Tenover. 1997. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:135-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones, M. E., R. S. Blosser-Middleton, C. Thornsberry, J. A. Karlowsky, and D. F. Sahm. 2003. The activity of levofloxacin and other antimicrobials against clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae collected worldwide during 1999-2002. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 47:579-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence, L. E., M. Frosco, B. Ryan, S. Chaniewski, H. Yang, D. C. Hooper, and J. F. Barrett. 2002. Bactericidal activities of BMS-284756, a novel des-F(6)-fluoroquinolone, against Staphylococcus aureus strains with topoisomerase mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:191-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low, D. E., M. Muller, C. L. Duncan, B. M. Willey, J. C. de Azavedo, A. McGeer, B. N. Kreiswirth, S. Pong-Porter, and D. J. Bast. 2002. Activity of BMS-284756, a novel des-fluoro(6) quinolone, against Staphylococcus aureus, including contributions of mutations to quinolone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1119-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald, L. C. 2006. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in health care-associated pathogens and effect on treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl. 2):S65-S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 6th ed. M7-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2004. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria; approved standard, 6th ed. M11-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 18.Ng, E. Y., M. Trucksis, and D. C. Hooper. 1994. Quinolone resistance mediated by norA: physiologic characterization and relationship to flqB, a quinolone resistance locus located on the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1345-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikaido, H. 1998. Multiple antibiotic resistance and efflux. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:516-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pankush, G. A., and P. C. Appelbaum. 2005. Postantibiotic effect of DX-619 against 16 gram-positive organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3963-3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson, D. L., and R. A. Bonomo 2005. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:657-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poole, K. 2004. Resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61:2200-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pucci, M. J., J. J. Bronson, J. F. Barrett, K. L. DenBleyker, L. F. Discotto, J. C. Fung-Tomc, and Y. Ueda. 2004. Antimicrobial evaluation of nocathiacins, a thiazole peptide class of antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3697-3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Truong-Bolduc, Q. C., P. M. Dunman, J. Strahilevitz, S. J. Projan, and D. C. Hooper. 2005. MgrA is a multiple regulator of two new efflux pumps in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187:2395-2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waites, K. B., L. B. Duffy, T. Schmid, D. Crabb, M. S. Pate, and G. H. Cassell. 1991. In vitro susceptibilities of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum to sparfloxacin and PD 127391. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1181-1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, Q., E. Lucien, A. Hashimoto, G. C. G. Pais, D. M. Nelson, Y. Song, J. A. Thanassi, C. W. Marlor, C. L. Thoma, J. Cheng, S. D. Podos, Y. Ou, M. Deshpande, M. J. Pucci, D. D. Buechter, B. J. Bradbury, and J. A. Wiles. 2007. Isothiazoloquinolones with enhanced antistaphylococcal activities against multi-drug-resistant strains: effects of structural modifications at the 6-, 7-, and 8-positions. J. Med. Chem. 50:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiles, J. A., Q. Wang, E. Lucien, A. Hashimoto, Y. Song, J. Cheng, C. Marlor, Y. Ou, S. D. Podos, J. A. Thanassi, C. L. Thoma, M. Deshpande, M. J. Pucci, and B. J. Bradbury. 2005. Isothiazoloquinolones containing functionalized aromatic hydrocarbons at the 7-position: synthesis and in vitro activity of a series of potent antibacterial agents with diminished cytotoxicity in human cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16:1272-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiles, J. A., Y. Song, Q. Wang, E. Lucien, A. Hashimoto, C. Marlor, Y. Ou, S. D. Podos, J. A. Thanassi, C. L. Thoma, M. Deshpande, M. J. Pucci, and B. J. Bradbury. 2006. Biological evaluation of isothiazoloquinolones containing aromatic heterocycles at the 7-position: in vitro activity of a series of potent antibacterial agents that are effective against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16:1277-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]