Abstract

A Candida krusei strain from a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia that displayed reduced susceptibility to echinocandin drugs contained a heterozygous mutation, T2080K, in FKS1. The resulting Phe655→Cys substitution altered the sensitivity of glucan synthase to echinocandin drugs, consistent with a common mechanism for echinocandin resistance in Candida spp.

Clinical antifungal resistance in fungi has been best characterized with azole drugs and is associated with a variety of mechanisms including direct modification of the target enzyme, levels of the target enzyme, decreased drug accumulation due to efflux pump overexpression, or some combination of these mechanisms (15). Less is known about reduced echinocandin susceptibility (RES), but resistance in Candida spp. has been associated only with mutations in the Fks1p subunit of the target enzyme (1,3)-β-d-glucan synthase (4-6, 10). Hakki et al. recently reported a case of invasive and oropharyngeal candidiasis caused by a Candida krusei isolate that developed RES after caspofungin (CFG) therapy. The preliminary evaluation did not reveal any modification of the FKS1 gene sequence in the isolate with reduced susceptibility (2). To determine if the RES phenotype in this strain could be due to a different mechanism, pre- and post-CFG treatment strains were further assessed for genetic and biochemical modifications of glucan synthase.

Echinocandin susceptibility testing with CFG, micafungin, and anidulafungin was performed in triplicate using the broth microdilution method of CLSI (formerly NCCLS) document M27-A2 (8) with modifications (10). C. krusei strains (2) Ck98 (pretreament) and Ck100 (posttreatment) were grown with vigorous shaking at 30°C to early-stationary phase in YPD broth (2% yeast extract, 4% Bacto peptone, 4% dextrose). Glucan synthase isolation and CFG titration were done as described previously (10). Inhibition curves and 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were determined using a sigmoidal response (variable-slope) curve and a two-site competition fitting algorithm with GraphPad Prism, version 4.0, software (Prism Software, Irvine, CA). Genomic DNA, obtained twice from each of five separate colonies, was extracted from cells grown overnight in YPD broth medium with the Q-Biogene (Irvine, CA) FastDNA kit. PCR amplification was performed on an iCycler thermocycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The FKS1 genes from both strains were PCR amplified using Sure-Pol DNA polymerase (Denville Scientific Inc., Metuchen, NJ). DNA sequencing of the 5.9-kb gene was performed with a CEQ dye terminator cycle sequencing Quick Start kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Sequencing analyses were done with the CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and with the BioEdit sequence alignment editor (Ibis Therapeutics, Carlsbad, CA).

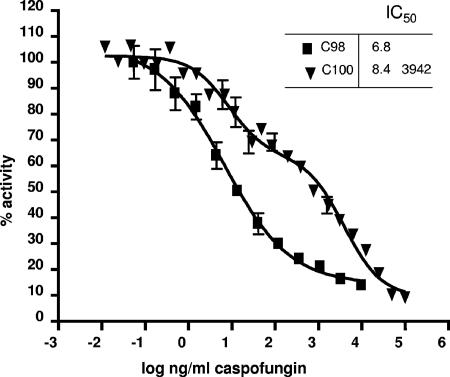

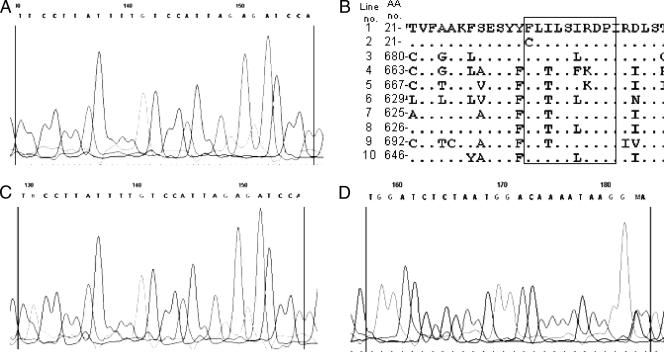

The MICs of echinocandin drugs for strain Ck-100 were 16- to 32-fold higher than those for the susceptible pretreatment strain, Ck-98 (Table 1), as previously reported (2). Moreover, the CFG MIC for Ck-100 exceeded the maximum range of 1 μg/ml reported for several large collections of clinical isolates using the CLSI M27-A2 method (9, 11-14). The reduced microbiological susceptibility of Ck-100 to CFG was confirmed in glucan synthase enzyme assays. A standard monophasic inhibition curve was obtained for Ck-98, yielding an IC50 of 6.8 ng/ml (Fig. 1). In contrast, biphasic inhibition was obtained for the product-entrapped enzyme from strain Ck-100, with IC50s of 8.4 ng/ml and 3,942 ng/ml (Fig. 1). The presence of two distinct inflection points (two IC50s) suggested a possible heterozygous genotype, as has been observed previously with Candida albicans (5, 6, 10). DNA sequence analysis of the entire fks1 gene uncovered heterozygosity at a single nucleotide position, nucleotide T2080K, based on GenBank accession no. EF426563 (equivalent to nucleotide T2629 in C. albicans GenBank accession no. D88815). Both the wild-type and G-substituted fks1 genes were observed in each of the five PCR products analyzed from strain Ck-100 (Fig. 2C and D). This nucleotide heterozygosity results in deduced amino acid heterogeneity—the wild type TTC codon encoding F and the modified TGC codon encoding C (Fig. 2B). None of the PCR products amplified from Ck-98 genomic DNA shared this nucleotide substitution (Fig. 2A). Failure to detect mutations in FKS1 previously (2) likely results from the analysis of only one cloned allele. Since C. krusei is a diploid or aneuploid organism (3, 17), the cloning of one allele or another in a bacterial plasmid is a matter of chance.

TABLE 1.

Echinocandin susceptibilities of C. krusei clinical strains

| C. krusei isolate | MIC (μg/ml)a of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspofungin | Micafungin | Anidulafungin | |

| Ck-98 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ck-100 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

Geometric mean (three repetitions on three separate days).

FIG. 1.

CFG inhibition profiles for product-entrapped glucan synthases. Enzyme complexes were obtained from pretreatment (Ck-98) (squares) and posttreatment (Ck-100) (triangles) C. krusei strains. Inhibition curves and IC50s (in nanograms per milliliter) were obtained using a sigmoidal response (variable-slope) curve (strain Ck-98) and a two-site competition fitting algorithm (strain Ck-100).

FIG. 2.

DNA sequencing chromatograms and amino acid sequence alignment for C. krusei strains. (A) C. krusei strain Ck-98 Fks1p HS1 (forward primer). (B) Sequence alignments of the Fks1p HS1 region (boxed) in different fungal species. Line 1, C. krusei wild-type allele (GenBank accession no. AAY40291.1); line 2, C. krusei Ck-100 mutated allele; line 3, Yarrowia lipolytica (XP_504213); line 4, Aspergillus fumigatus (AAB58492); line 5, Coccidioides immitis (EAS36399); line 6, C. albicans (XP_721429); line 7, Debaryomyces hansenii (XP 457762); line 8, Kluyveromyces lactis (CAH02189); line 9, Schizosaccharomyces pombe (NP_588501); line 10, Saccharomyces cerevisae (AAZ22447). (C and D) C. krusei strain Ck-100 Fks1p HS1. (C) Forward primer; (D) reverse primer.

The amino acid substitution at this position in C. krusei Fks1p is located in the highly conserved “hot spot 1” region of the protein (Fig. 2B) (10). Heterozygous amino acid changes in this region are associated with CFG resistance in both Saccharomyces cerevisiae laboratory strains and C. albicans clinical isolates (5, 6, 10). However, the only other reported C. krusei clinical isolate with RES had a predicted R1361G substitution in “hot spot 2” of Fks1p (10). Thus, clinical isolate Ck-100 is the first echinocandin-resistant C. krusei strain to be associated with a mutation in “hot spot 1.”

The results obtained in this work highlight the need to monitor C. krusei infections treated with echinocandin drugs for the development of resistance. This is especially important because mortality from C. krusei, like that from other Candida spp., remains high (7, 16, 18) and treatment options are limited due to intrinsic resistance to fluconazole (1).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charlier, C., E. Hart, A. Lefort, P. Ribaud, F. Dromer, D. W. Denning, and O. Lortholary. 2006. Fluconazole for the management of invasive candidiasis: where do we stand after 15 years? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57384-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakki, M., J. F. Staab, and K. A. Marr. 2006. Emergence of a Candida krusei isolate with reduced susceptibility to caspofungin during therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 502522-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobsen, M. D., N. A. Gow, M. C. Maiden, D. J. Shaw, and F. C. Odds. 22 Nov. 2006. Strain typing and determination of population structure of Candida krusei determined by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01549-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Katiyar, S., M. Pfaller, and T. Edlind. 2006. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata clinical isolates exhibiting reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 502892-2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laverdiere, M., R. G. Lalonde, J. G. Baril, D. C. Sheppard, S. Park, and D. S. Perlin. 2006. Progressive loss of echinocandin activity following prolonged use for treatment of Candida albicans oesophagitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57705-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller, C. D., B. W. Lomaestro, S. Park, and D. S. Perlin. 2006. Progressive esophagitis caused by Candida albicans with reduced susceptibility to caspofungin. Pharmacotherapy 26877-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrell, M., V. J. Fraser, and M. H. Kollef. 2005. Delaying the empiric treatment of candida bloodstream infection until positive blood culture results are obtained: a potential risk factor for hospital mortality. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 493640-3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard, 2nd ed. NCCLS document M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 9.Ostrosky-Zeichner, L., J. H. Rex, P. G. Pappas, R. J. Hamill, R. A. Larsen, H. W. Horowitz, W. G. Powderly, N. Hyslop, C. A. Kauffman, J. Cleary, J. E. Mangino, and J. Lee. 2003. Antifungal susceptibility survey of 2,000 bloodstream Candida isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 473149-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park, S., R. Kelly, J. N. Kahn, J. Robles, M. J. Hsu, E. Register, W. Li, V. Vyas, H. Fan, G. Abruzzo, A. Flattery, C. Gill, G. Chrebet, S. A. Parent, M. Kurtz, H. Teppler, C. M. Douglas, and D. S. Perlin. 2005. Specific substitutions in the echinocandin target Fks1p account for reduced susceptibility of rare laboratory and clinical Candida sp. isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 493264-3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfaller, M. A., L. Boyken, R. J. Hollis, S. A. Messer, S. Tendolkar, and D. J. Diekema. 2006. Global surveillance of in vitro activity of micafungin against Candida: a comparison with caspofungin by CLSI-recommended methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 443533-3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfaller, M. A., L. Boyken, R. J. Hollis, S. A. Messer, S. Tendolkar, and D. J. Diekema. 2005. In vitro activities of anidulafungin against more than 2,500 clinical isolates of Candida spp., including 315 isolates resistant to fluconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435425-5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, and R. N. Jones. 2003. In vitro activities of caspofungin compared with those of fluconazole and itraconazole against 3,959 clinical isolates of Candida spp., including 157 fluconazole-resistant isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 471068-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roling, E. E., M. E. Klepser, A. Wasson, R. E. Lewis, E. J. Ernst, and M. A. Pfaller. 2002. Antifungal activities of fluconazole, caspofungin (MK0991), and anidulafungin (LY 303366) alone and in combination against Candida spp. and Crytococcus neoformans via time-kill methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 4313-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanglard, D., and F. C. Odds. 2002. Resistance of Candida species to antifungal agents: molecular mechanisms and clinical consequences. Lancet Infect. Dis. 273-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberger, M., L. Leibovici, S. Perez, Z. Samra, I. Ostfeld, I. Levi, E. Bash, D. Turner, A. Goldschmied-Reouven, G. Regev-Yochay, S. D. Pitlik, and N. Keller. 2005. Characteristics of candidaemia with Candida albicans compared with non-albicans Candida species and predictors of mortality. J. Hosp. Infect. 61146-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whelan, W. L., and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1988. Auxotrophic heterozygosities and the ploidy of Candida parapsilosis and Candida krusei. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 26163-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wisplinghoff, H., T. Bischoff, S. M. Tallent, H. Seifert, R. P. Wenzel, and M. B. Edmond. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39309-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]