Abstract

Fosmidomycin-clindamycin therapy given every 12 h for 3 days was compared with a standard single oral dose of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. The two treatments showed comparably good tolerabilities and had an identical high degree of efficacy of 94% in a randomized trial carried out with 105 Gabonese children aged 3 to 14 years with uncomplicated malaria. These antimalarials merit further clinical exploration.

The World Health Organization has recommended the use of antimalarial combination therapy and especially artemisinin-based combinations to combat drug-resistant malaria in Africa. The adequate implementation of this recommendation still seems distant in many parts of Africa (22). Other efficient options are needed for the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Africa, and various successes have been achieved in studies of antimalarial combinations (9).

Fosmidomycin is the first representative of a new class of antimalarial drugs (8, 12, 15, 19). Clindamycin is another promising drug with a short elimination half-life and a good safety and tolerability profile for antimalarial therapy (6, 11). The combination of fosmidomycin plus clindamycin (FC) is promising as antimalarial treatment and has a novel and independent mechanism of action (20). Pilot studies have shown that this antimalarial combination is safe, well tolerated, and efficacious against P. falciparum malaria (3, 4). Its short course fulfills many criteria for a first-line antimalarial treatment option in countries where malaria is endemic (5).

Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) is recommended as an antimalarial in Gabon, where it is widely used because of its practical advantage of availability and ease of administration. However, there have been reports of the decreasing efficacy of SP in Gabon (1, 13, 14, 21).

We report here on a study that evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of FC compared to those of a standard oral dose of SP for the treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in a pediatric outpatient population.

The study was conducted from July 2005 to March 2006 in Lambaréné, Gabon, a semiurban settlement with approximately 30,000 inhabitants. Malaria transmission is moderate and perennial (18). Children aged 3 to 14 years presenting in the outpatient department of the Medical Research Unit, Albert Schweitzer Hospital, with asexual parasitemia and a temperature of ≥37.5°C or a recent history of fever were eligible for enrollment. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the International Foundation of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambaréné.

A study physician examined all eligible children at enrollment and recorded the blood pressure, pulse, and axillary temperature. The laboratory data recorded were the densities of the asexual and sexual forms of the malaria parasite (16); the levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit; the white blood cell count; the thrombocyte count; and the creatinine, total bilirubin, and alanine aminotransferase levels. Filter-paper blots were taken at enrollment and on the days of reappearance of parasitemia to distinguish reinfection from recrudescence by PCR by using the polymorphic region of the merozoite surface antigens 1 and 2 for typing of the parasite genotypes (10).

Treatment was allocated on the basis of a computer-generated list, with randomization of the individuals in blocks of 10. The code was concealed in sealed opaque numbered envelopes. The doses of fosmidomycin and clindamycin (Allphamed PHARBIL, Göttingen, Germany) used in the combination were 30 mg/kg of body weight and 10 mg/kg, respectively, and FC was given every 12 h for 3 days. The doses of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine (coformulation; Brown and Burke Pharmaceutical Ltd., Hosur, India) used were 25 mg/kg and 1.25 mg/kg, respectively, and SP was given as a single dose. The drugs were administered with water by a study clinician. A subject was withdrawn from the trial if a redose was vomited, and these patients were subsequently treated with oral artesunate-amodiaquine (Arsucam; Sanofi-Synthelabo, France). Follow-up visits were scheduled for all study subjects on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 after the commencement of treatment with the trial medication (day 0).

Our original sample size of 160 children for a noninferiority test (2) was not attained because the study drug (fosmidomycin) expired after 105 patients were recruited and the trial was terminated.

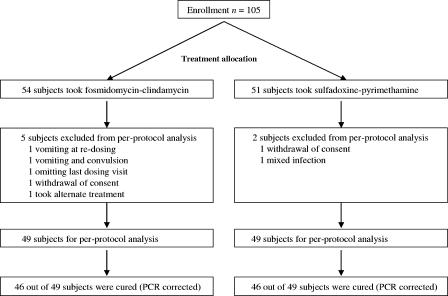

Efficacy was calculated in the per-protocol population of 98 children who completed the 3-day regimen of FC every 12 h or the single dose of SP and had a follow-up visit on day 28 (+1 week). Safety and tolerance were evaluated in the intention-to-treat population of 105 children who took at least the first dose of FC or the single dose of SP (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Study flow chart.

The treatment groups were comparable in terms of their clinical features (Table 1) and laboratory indices at the time of enrollment. The proportion of subjects cured in the per-protocol population was 94% (46 of 49) for both groups (P = 0.20). In the intention-to-treat population, the proportions of subjects cured were 90% (46 of 51) for the SP group and 85% (46 of 54) for the FC group (P = 0.50). There were two early treatment failures in the SP group. The subjects in the FC groups had a shorter parasite elimination time and experienced a faster recovery from fever. Although one child in the FC group had a serious adverse event (convulsion) on day 1, there were more adverse events in the SP group and all adverse events resolved spontaneously (Table 2). The gametocyte carriage rate was similar in both groups (Table 3).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | FC | SP |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 54 | 51 |

| No. (%) male | 31 (57) | 27 (53) |

| No. (%) female | 23 (43) | 24 (47) |

| Age (yr)a | 8 (3) | 8 (4) |

| Wt (kg)a | 23 (8) | 24 (10) |

| No. with parasitemia at admissionb | 14,400 (5,150-43,600) | 14,800 (6,000-51,700) |

| Axillary temp (°C)a | 37.7 (1.1) | 37.4 (1.0) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)a | 86 (10) | 87 (11) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)a | 47 (11) | 49 (11) |

| Pulse (no. of beats/min)a | 102 (14) | 101 (12) |

Arithmetric mean (standard deviation).

Median (quartiles).

TABLE 2.

Adverse events reported during follow-up period

| Adverse event | No. (%) of patients

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCa | SP | ||

| Headache | 18 (33) | 22 (43) | 0.5 |

| Chills | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 1.0 |

| Myalgia | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | 0.7 |

| Nausea | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 0.4 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (6) | 7 (14) | 0.2 |

| Abdominal pain | 17 (32) | 16 (32) | 1.0 |

| Anorexia | 7 (14) | 15 (29) | 0.1 |

| Vomiting | 1 (2) | 13 (26) | 0.002 |

| Dizziness | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.5 |

| Coughing | 7 (14) | 13 (26) | 0.2 |

| Pruritus | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.2 |

| Insomnia | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.5 |

| Total | 64 | 100 | 0.05 |

One subject (1%) in the FC treatment group had a serious adverse event (convulsion).

TABLE 3.

Day 28 cure rates

| Treatment | Per-protocol population

|

Intention-to-treat population

|

Parasite clearance time (h)b | Mean fever clearance time (h)b,c | No. (%) of patients with early treatment failures | Gametocyte carrier rate (no. [%] of patients)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | No. of patients cured on day 28a | Cure ratea | No. of patients | No. of patients cured on day 28a | Cure ratea | Admission | Follow-up | ||||

| FC | 49 | 46 | 94 (83-98) | 54 | 46 | 85 (73-92) | 38 (26-34) | 33 (26-41) | 0 | 1 (2) | 18 (33) |

| SP | 49 | 46 | 94 (83-98) | 51 | 46 | 90 (79-96) | 41 (36-46) | 38 (29-46) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 18 (35) |

| P value | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.3d | 0.4d | 0.2d | 0.5d | 0.9d | ||||

PCR-corrected cure rate; values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Values are means (95% confidence intervals).

Temperature <37.5°C.

Student's t test.

We found that FC administered to Gabonese children between 3 and 14 years of age with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria was well tolerated and achieved a high degree of efficacy of 94% by day 28. A standard single dose of SP was also well tolerated and achieved the same degree of efficacy as FC. This level of efficacy was notably higher than that expected from previous studies (1, 13, 14).

Although the artemisinin combinations are the recommended standard antimalarial treatments in Africa, their availability and use are limited by cost in Gabon, as in other Africa countries. Considering the previous reports of efficacy from other studies of FC, it seems to be the only other antimalarial combination that is similar to the artemisinin combinations in that it has a short half-life and shows good efficacy rates comparable to those of the artemisinin combinations on day 28. Furthermore, this short-course FC combination has been shown to be devoid of concerns about safety in comparison to the concerns that arise about other similarly effective antimalarials (3, 4, 5).

A possible drawback lies in the necessity of repeated dosing (every 12 h for 3 days), which can reduce the rate of treatment compliance, and a possible rise in the number of gametocyte carriers seen in previous studies. In view of the relatively small sample size analyzed in this study, further clinical exploration would have to address these limitations.

In conclusion, the FC combination is a promising new antimalarial, and our findings further consolidate efforts toward its development as a potential antimalarial therapy suitable for African children. The recommendation of SP therapy as second-line antimalarial in Gabon merits reevaluation for intermittent preventive treatment in infants or as a suitable antimalarial combination partner when artemisinin combination therapies are unavailable (7, 17).

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest concerning the work reported in this paper.

This study was supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung of Germany.

We are grateful to the staff of the Medical Research Unit, the Pediatric Ward of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital, and the children and their parents for participation in our study. We thank Brigitte Migombet, Ariane Ntseyi, M. Nkeyi and A. Ndzengue for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 February 2007.

The registration number for this trial is NCT00214643.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloueche, A., W. Bailey, S. Barton, P. Chimpeni, C. O. Falade, F. A. Fehintola, J. Horton, S. Jaffar, T. Kanyok, P. G. Kremsner, J. G. Kublin, T. Lang, M. A. Missinou, C. Mkandala, A. M. Oduola, Z. Premji, L. Robertson, A. Sowunmi, S. A. Ward, and P. A. Winstanley. 2004. Comparison of chlorproguanil-dapsone with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in young African children: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 3631843-1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwelder, W. C. 1982. ‘Proving the null hypothesis’ in clinical trials. Controlled Clin. Trials 3345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrmann, S., A. A. Adegnika, P. B. Matsiegui, S. Issifou, A. Schindler, D. P. Mawili-Mboumba, T. Baranek, J. Wiesner, H. Jomaa, and P. G. Kremsner. 2004. Fosmidomycin-clindamycin for Plasmodium falciparum infections in African children. J. Infect. Dis. 189901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrmann, S., S. Issifou, G. Esser, A. A. Adegnika, M. Ramharter, P. B. Matsiegui, S. Oyakhirome, D. P. Mawili-Mboumba, M. A. Missinou, J. F. J. Kun, H. Jomaa, and P. G. Kremsner. 2004. Fosmidomycin-clindamycin for the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 1901534-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrmann, S., I. Lundgren, S. Oyakhirome, B. Impouma, P. B. Matsiegui, A. A. Adegnika, S. Issifou, J. F. J. Kun, D. Hutchinson, J. Wiesner, H. Jomaa, and P. G. Kremsner. 2006. Fosmidomycin plus clindamycin for treatment of pediatric patients aged 1 to 14 years with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 502713-2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeHaan, R. M., C. M. Metzler, D. Schellenberg, W. D. VandenBosch, and E. L. Masson. 1972. Pharmacokinetic studies of clindamycin hydrochloride in humans. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 6105-119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenwood, B. 2004. Treating malaria in Africa: sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine may still have a future despite reports of resistance. BMJ 328534-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jomaa, H., J. Wiesner, S. Sanderbrand, B. Altincicek, C. Weidemeyer, M. Hintz, I. Turbachova, M. Eberl, J. Zeidler, H. K. Lichtenthaler, D. Soldati, and E. Beck. 1999. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 2851573-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kremsner, P. G., and S. Krishna. 2004. Antimalarial combinations. Lancet 364285-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kun, J. F. J., M. A. Missinou, B. Lell, M. Soric, H. Knoop, B. Bojowald, O. Dangelmaier, and P. G. Kremsner. 2002. New emerging Plasmodium falciparum genotypes in children during the transition phase from asymptomatic parasitemia to malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66653-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lell, B., and P. G. Kremsner. 2002. Clindamycin as an antimalarial drug: review of clinical trials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 462315-2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lell, B., R. Ruangweerayut, J. Wiesner, M. A. Missinou, A. Schindler, T. Baranek, M. Hintz, D. Hutchinson, H. Jomaa, and P. G. Kremsner. 2003. Fosmidomycin, a novel chemotherapeutic agent for malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47735-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lell, B., L. G. Lehman, J. R. Schmidt-Ott, J. Handschin, and P. G. Kremsner. 1998. Malaria chemotherapy trial at a minimal effective dose of mefloquine/sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine compared with equivalent doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine or mefloquine alone. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 58619-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzger, W., B. Mordmuller, W. Graninger, U. Bienzle, and P. G. Kremsner. 1995. Sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine or chloroquine/clindamycin treatment of Gabonese school children infected with chloroquine resistant malaria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36723-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Missinou, M. A., S. Borrmann, A. Schindler, S. Issifou, A. A. Adegnika, P. B. Matsiegui, R. Binder, B. Lell, J. Wiesner, T. Baranek, H. Jomaa, and P. G. Kremsner. 2002. Fosmidomycin for malaria. Lancet 3601941-1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Planche, T., S. Krishna, M. Kombila, K. Engel, J. F. Faucher, E. Ngou-Milama, and P. G. Kremsner. 2001. Comparison of methods for the rapid laboratory assessment of children with malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65599-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schellenberg, D., C. Menendez, E. Kahigwa, J. Aponte, J. Vidal, M. Tanner, H. Mshinda, and P. Alonso. 2001. Intermittent treatment for malaria and anaemia control at time of routine vaccinations in Tanzanian infants: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 3571471-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sylla, E. H., J. F. Kun, and P. G. Kremsner. 2000. Mosquito distribution and entomological inoculation rates in three malaria-endemic areas in Gabon. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 94652-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiesner, J., S. Borrmann, and H. Jomaa. 2003. Fosmidomycin for the treatment of malaria. Parasitol. Res. 90S71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiesner, J., D. Henschker, D. B. Hutchinson, E. Beck, and H. Jomaa. 2002. In vitro and in vivo synergy of fosmidomycin, a novel antimalarial drug, with clindamycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 462889-2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkler, S., C. Brandts, W. H. Wernsdorfer, W. Graninger, U. Bienzle, and P. G. Kremsner. 1994. Drug sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum in Gabon. Activity correlations between various antimalarials. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 45214-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. 2003. Position on WHO's Roll Back Malaria Department on malaria treatment policy. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.