Abstract

Nitrate injection into oil reservoirs can prevent and remediate souring, the production of hydrogen sulfide by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB). Nitrate stimulates nitrate-reducing, sulfide-oxidizing bacteria (NR-SOB) and heterotrophic nitrate-reducing bacteria (hNRB) that compete with SRB for degradable oil organics. Up-flow, packed-bed bioreactors inoculated with water produced from an oil field and injected with lactate, sulfate, and nitrate served as sources for isolating several NRB, including Sulfurospirillum and Thauera spp. The former coupled reduction of nitrate to nitrite and ammonia with oxidation of either lactate (hNRB activity) or sulfide (NR-SOB activity). Souring control in a bioreactor receiving 12.5 mM lactate and 6, 2, 0.75, or 0.013 mM sulfate always required injection of 10 mM nitrate, irrespective of the sulfate concentration. Community analysis revealed that at all but the lowest sulfate concentration (0.013 mM), significant SRB were present. At 0.013 mM sulfate, direct hNRB-mediated oxidation of lactate by nitrate appeared to be the dominant mechanism. The absence of significant SRB indicated that sulfur cycling does not occur at such low sulfate concentrations. The metabolically versatile Sulfurospirillum spp. were dominant when nitrate was present in the bioreactor. Analysis of cocultures of Desulfovibrio sp. strain Lac3, Lac6, or Lac15 and Sulfurospirillum sp. strain KW indicated its hNRB activity and ability to produce inhibitory concentrations of nitrite to be key factors for it to successfully outcompete oil field SRB.

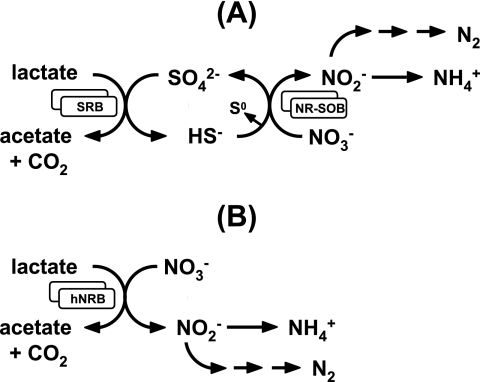

Souring, the undesirable production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in oil reservoirs by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), is a common problem during secondary oil recovery when water is injected to produce the remaining oil. SRB reduce sulfate in the injection water to sulfide, while oxidizing degradable organic electron donors present in the oil reservoir. The concentration of sulfate introduced depends on the source of the injection water and is especially high (∼30 mM) when seawater is injected during offshore operations. Because large volumes of water are injected (typically 10,000 m3/day), large amounts of biogenic sulfide can be coproduced with the oil and gas, up to 1,100 kg per day (21). Removal of sulfide is needed in view of health and safety concerns and to reduce the risk of pipeline corrosion (15) and other negative effects. Although sulfides can be removed chemically following production, in situ elimination through continuous nitrate injection has also proven to be effective, as demonstrated both in model column studies (16, 23, 29) and in the field (20, 21, 34, 35). Nitrate injection changes the microbial community in the subsurface from mainly SRB to one enriched in nitrate-reducing bacteria (NRB), which include the nitrate-reducing, sulfide-oxidizing bacteria (NR-SOB) that oxidize H2S directly (Fig. 1A) and the heterotrophic NRB (hNRB), which compete with SRB for degradable organic electron donors (Fig. 1B) and thus potentially prevent SRB metabolism. Lactate, representing degradable oil organics, is shown to be oxidized incompletely to acetate and CO2 in Fig. 1. Other compounds, including the volatile fatty acids acetate, propionate, and butyrate may be oxidized completely to CO2, although complete oxidation of acetate was not observed in the current study. Both types of NRB also promote SRB inhibition via production of nitrite (10), formed in both nitrate reduction pathways depicted in Fig. 1. Although lactate-utilizing SRB and hNRB are common in oil fields, lactate concentrations are low, indicating rapid turnover. Lactate may form by fermentation of cell wall material or of carbohydrate polymers (e.g., xanthans) injected to enhance oil recovery.

FIG. 1.

Impact of nitrate on the oil field sulfur cycle. (A) Sulfide produced by SRB activity can be recycled to sulfate or sulfur by NR-SOB reducing nitrate to nitrogen (denitrification) or ammonia (DNRA). (B) hNRB compete with SRB for organic electron donors, such as lactate, excluding sulfide production by SRB. Many SRB and hNRB oxidize lactate incompletely to acetate and CO2 as shown. The overall reactions in panels A and B are the same: the oxidation of lactate with nitrate.

Because sulfide is at best an intermediate in the nitrate-dependent oxidation of oil organics like lactate, the nitrate dose required to eliminate sulfide is dictated by the lactate concentration, not by the sulfate concentration. This was shown by Hubert et al. (16) with a bioreactor injected with 25, 12.5, or 6.25 mM lactate and 7.8, 4.7, or 3.0 mM sulfate. Because SRB were a prominent component in all bioreactor communities that were analyzed (16), it was concluded that souring control was due primarily to NR-SOB activity, as in Fig. 1A. The goals of the current work are to (i) determine the properties of the main NRB present in a similar bioreactor experiment and (ii) evaluate whether SRB remain dominant community members at sulfate concentrations lower than those used in previous work (16), i.e., to determine the lower limit of the sulfate concentration at which effective sulfur cycling can still occur.

(Part of this work was presented at the NACE Annual General Meeting held in March 2006 in San Diego, CA [16a].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples and media.

All cultures originated from the water produced from the Coleville oil field located near Kindersley, Saskatchewan, in western Canada. The water produced from the oil field sampled in August 2000 was used to inoculate bioreactors in previous studies (15, 16) from which most strains described here were isolated. A sample of the water produced obtained in April 2002 was used to inoculate the bioreactor in the present study and was also plated directly for further strain isolations. Coleville synthetic brine (CSB), mimicking the cation and anion concentrations in this water produced from the oil field as formulated by Gevertz et al. (5), was prepared as described by Nemati et al. (24) and altered to modified CSB (mCSB), which contains 12.5 mM lactate and the sulfate and nitrate concentrations indicated in Table 1. CSB-A, an alternate, simpler formulation of CSB medium, was prepared as described by Hubert et al. (16). The acetate-containing NRB medium of Gieg et al. (6) and saline Postgate C (sPGC), a rich medium containing yeast extract, lactate, and sulfate (24) were also used.

TABLE 1.

Sulfate and nitrate concentrations in mCSB medium used in the bioreactor experimenta

| Compound | Concn (mM) used | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfate | 6.0 | 2.0 | 0.75 | 0.013b |

| Nitrate | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | |

| 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| 12.5 | ||||

| 15.0 | ||||

The lactate concentration was 12.5 mM throughout.

Sulfate concentration due to the addition of trace element solution.

Bioreactor.

An up-flow, packed-bed bioreactor was set up and operated as described elsewhere (16). A glass column (4.5 × 64 cm) equipped with five sampling ports was packed with sand (average diameter, 225 μm), autoclaved, and filled with N2-purged, filter-sterilized mCSB medium containing 12.5 mM lactate and 6 mM sulfate. Each sampling port was inoculated with 15 ml of the water produced from the oil field, and incubation in the absence of flow allowed an SRB community to establish. Following this, the flow rate was gradually increased to 9 ml/h to encourage further SRB biofilm development within the sand matrix. Under these conditions, the residence time was about 24 h. Following this 6-week start-up period, the sulfate and/or nitrate concentrations were changed according to the sequence in Table 1, which outlines the series of experiments performed in the same bioreactor. Operation for at least 1 week under changed conditions allowed establishment of a steady state as indicated by constant concentrations of sulfide, sulfate, nitrate, nitrite, lactate, and acetate and constant redox potential (Eh).

Isolation of oil field NRB.

Samples of Coleville oil field-produced water and samples from bioreactors operated as part of a previous study (15) were diluted and spread on plates containing nitrate, a carbon and energy substrate, and 15 g/liter of agar. NRB plating media included mCSB, CSB-A, and acetate-containing NRB medium (6). Following pouring, NRB medium plates were allowed to dry in air before being transferred to an anaerobic hood (Coy Laboratory Products) with an atmosphere of 5% (vol/vol) H2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2. Single colonies were suspended in 1 ml of the corresponding liquid medium and inoculated into serum bottles containing 100 ml CSB or CSB-A with lactate and nitrate. Following growth at room temperature, cultures were maintained by periodic transfer. Their ability to oxidize lactate with nitrate was confirmed, and their ability to oxidize sulfide (2 to 4 mM) with nitrate was assessed in CSB or CSB-A medium. Sulfate reduction was tested in mCSB medium. The concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, lactate or acetate and Eh were determined at regular intervals in batch cultures.

Phylogenetic analyses.

DNA isolated from 100-ml cultures was used for dot blot cross-hybridization analyses as described elsewhere (34). NRB that were genomically distinct from each other and from 47 previously isolated oil field standards (defined as strains with low genomic cross-hybridization) (34) were thus identified. 16S rRNA gene sequences for NRB strains NO3B, N2, C4, C6, and KW were determined and deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers DQ228136, DQ228137, DQ228138, DQ228139, and DQ228140, respectively. Sequences for strains NO3A and NO2B were previously deposited under accession numbers AY135396 and AY135395, respectively (16). Amplification of 16S rRNA genes by PCR using universal primers f8 (27) and r1406 (13) was performed as described elsewhere (34). Automated sequencing was performed using these same primers on an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) by University Core DNA Services at the University of Calgary. Sequences with high homology to the sequences of the new isolates, as well as other sequences of interest, were retrieved from the GenBank database following BLAST searches (1). Sequence alignment, manual refinement of the alignment, and phylogenetic tree reconstruction were performed using the ARB software package (22). Maximum-likelihood trees were generated using FastDNAML software, and distance trees were generated using neighbor-joining algorithms. Bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates was performed for the neighbor-joining tree.

Cocultures of oil field NRB and SRB.

Oil field sulfate-reducing Desulfovibrio sp. strains Lac3, Lac6, and Lac15 (36), maintained in sPGC, were inoculated (2% [vol/vol]) into stoppered serum bottles containing CSB-A with lactate, sulfate, and nitrate concentrations as indicated and a headspace of 90% (vol/vol) N2 and 10% CO2. Sulfurospirillum sp. strain KW, maintained in CSB-A with lactate and nitrate, was inoculated (7% [vol/vol]) into these SRB cultures either at mid-log phase or at time zero. Washed-cell inocula of strain Lac15 or KW were used in some experiments to prevent inhibition of the SRB culture with nitrite, as well as of the NRB culture with components in SRB medium. Cells (2 ml of strain Lac15 in sPGC or 7 ml of strain KW in CSB-A) were centrifuged (10,000 × g; 10 min) in an anaerobic hood (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc.) and resuspended in 1 ml of medium, which was injected into serum bottles. Culture filtrates lacking cells were added by injecting aliquots from cultures of strain Lac15 or KW into serum bottles through a 0.2-μm filter.

Analytical procedures.

The composition of planktonic microbial communities was analyzed by reverse sample genome probing (RSGP), a technique in which denatured microbial genomic DNAs are spotted on macroarrays. Total community DNA, isolated from bioreactor samples, was labeled and hybridized with these genome arrays (25, 34) comprised of 54 standards, defined as genomically distinct isolates from different oil fields including the 5 new NRB standards (strains NO3B, N2, C4, C6, and KW) described in this study. The sulfide concentration was determined spectrophotometrically (3). The sulfate concentration was determined spectrophotometrically (25) or using a Waters 600E high-pressure liquid chromatograph (HPLC) with a Waters 423 conductivity detector, using a Waters IC-Pak high-capacity column and a borate/gluconate eluent (Waters) at 2 ml min−1. Nitrate and nitrite concentrations were determined using the same Waters 600E HPLC equipped with a Gilson Holochrome UV detector or a Gilson 151 UV/visible light detector, set at 200 nm. Nitrite concentrations were also determined spectrophotometrically (9). Ammonium was determined as described elsewhere (33). Lactate and acetate concentrations were determined using a Waters 600E HPLC equipped with a Waters 2487 UV detector at 220 nm, using an Alltech Prevail organic acid column (250 × 4.6 mm) and 25 mM KH2PO4 (pH 2.4) as the eluent at 1 ml min−1. Redox potential differences, ΔEh, were measured off-line using a microelectrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Eh = +222 mV) from Microelectrodes, Inc. (Bedford, NH). Eh was calculated as Eh = ΔEh + 222. The electrode was calibrated with an oxidation-reduction potential standard solution (Orion Research, Inc., Beverley, MA) with ΔEh = +424 mV at 20°C.

RESULTS

Isolation, physiology, and phylogeny of bioreactor NRB.

NRB were isolated on plating media containing lactate and nitrate and propagated on liquid media in which lactate was the sole electron donor for nitrate reduction. Following genomic cross-hybridization analysis, strains NO3B, N2, C4, C6, and KW, as well as NO2B (isolated previously [16]), were retained. Their phylogenetic association and physiological properties are presented here.

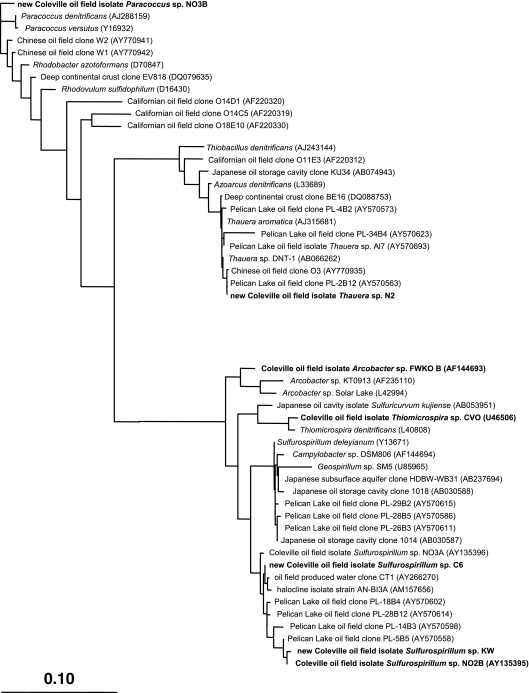

A 16S rRNA gene sequence-based phylogenetic tree that includes these hNRB strains, except for strain C4 for which a shorter 16S rRNA sequence (400 nucleotides [nt]) was obtained, is shown in Fig. 2. Sequences for two NR-SOB from the Coleville oil field, Thiomicrospira sp. strain CVO and Arcobacter sp. strain FWKO_B obtained previously (5), and many other oil field-derived sequences are also included. The new isolates from the Coleville oil field are all closely related to other bacteria from oil fields and other subsurface environments, based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (Fig. 2). Of particular interest are sequences from the Pelican Lake oil field, which is also found in western Canada, but unlike the Coleville oil field, has not experienced water injection for secondary oil recovery (7). The close relationships between sequences from these two reservoirs indicates these organisms to be widespread in these environments and suggests that the new Coleville isolates are indigenous reservoir microbes, not contaminants introduced during water injection.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA gene sequences from newly isolated oil field bacteria and related sequences from oil fields and other environments. Organisms represented on the RSGP genome array, including new NRB isolates from the Coleville reservoir, are shown in boldface type. The topology shown was obtained by comparing nearly full-length sequences using the maximum-likelihood method and is similar to topologies produced using other tree reconstruction approaches. The scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position.

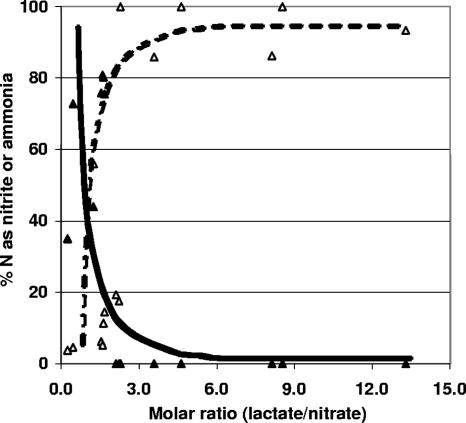

Like strains CVO and FWKO_B, strains C6, NO2B, and KW all belong to the epsilon division of the proteobacteria. Their closest cultured and characterized relative is Sulfurospirillum deleyianum, which grows by dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA) via nitrite (4). Strain KW similarly reduces nitrate (11 mM) to nitrite (9 mM) and ammonia (2 mM), while oxidizing lactate (8 mM decrease) incompletely to acetate (8 mM increase) and CO2 (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Interestingly, strain KW also coupled the reduction of nitrate (2 mM) to nitrite (0.5 mM) and ammonia (1.5 mM) to the oxidation of sulfide (3 mM) to sulfur or polysulfide (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). This was qualitatively indicated by the presence of a white precipitate and a yellow-colored medium, respectively. Sulfate was never detected as an end product of sulfide oxidation, even in medium with nitrate-to-sulfide ratios that did promote sulfate production by the NR-SOB Thiomicrospira sp. strain CVO (10). NR-SOB activity of these Sulfurospirillum spp. was modest compared to that of strain CVO, which couples the oxidation of sulfide to sulfur and sulfate with denitrification, i.e., reduction of nitrate to nitrite, NO, N2O, and N2 (5, 10). Lactate-to-nitrate ratios in hNRB medium determine whether nitrate reduction by Sulfurospirillum sp. strain KW yields nitrite or ammonia. When this ratio is high (nitrate limiting), more ammonia is produced, whereas when it is low (lactate limiting), nitrite production is favored (Fig. 3). Metabolism of strain KW was associated with high values of the environmental redox potential (+200 to +300 mV [see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material]). The metabolic properties of strains C6 and NO2B were similar to those of strain KW (results not shown).

FIG. 3.

Percentage of nitrite and ammonia formed as a function of the lactate-to-nitrate ratio. Sixteen separate cultures of oil field Sulfurospirillum spp. were grown at different lactate-to-nitrate ratios, as indicated on the x axis. The y axis represents the percentage fraction of the nitrate that was converted to nitrite (▴) or ammonia (▵) during DNRA.

Thauera sp. strain N2 did not form nitrite, ammonia, or acetate when oxidizing lactate with nitrate (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material), suggesting that CO2 and N2 were end products (not quantified). Thauera spp., belonging to the betaproteobacteria, are known to reduce nitrate by denitrification (28). Strain N2 was able to oxidize a range of other organic compounds (not shown). Paracoccus sp. strain NO3B has Paracoccus denitrificans as its closest cultured homolog, which, along with related members of the alphaproteobacteria, also reduce nitrate via denitrification (14). Strains N2 and NO3B did not reduce nitrate with sulfide as an electron donor; thus, they are hNRB, not NR-SOB. The partial 16S rRNA sequence of strain C4, isolated on acetate-containing NRB medium plates (6), indicated it to be phylogenetically close to Desulfomicrobium norvegicum, a sulfate reducer in the deltaproteobacteria. Hence, strain C4 is similar to some Desulfovibrio desulfuricans strains that can reduce both nitrate and sulfate (32).

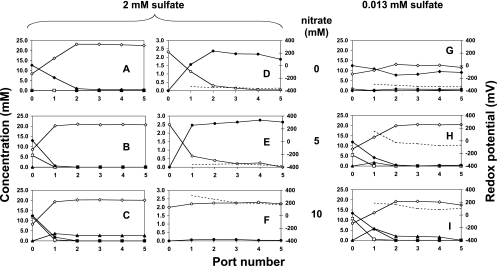

Souring control in bioreactors: effect of the sulfate concentration.

Packed-bed up-flow bioreactors inoculated with water produced from the Coleville oil field continuously received mCSB medium with a sulfate concentration of 6.0, 2.0, 0.75, or 0.013 mM, the latter representing the sulfate concentration present in the trace elements solution. The concentration of nitrate was always raised in 2.5 mM increments (Table 1), allowing establishment of steady-state conditions after each increase. The steady-state concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, nitrate, nitrite, lactate, and acetate along the vertical axis of the bioreactor are represented in Fig. 4 for ports 0 to 5, port 0 being the inflowing medium, for some of the experiments conducted. Data for 6 mM sulfate were similar to those obtained previously using the same medium (16) and are not shown. Because displacement of the bioreactor void volume took 24 h, the x axis can also be thought of as representing time with the points being spaced about 5 h apart. In the absence of nitrate, conversion of lactate to acetate (Fig. 4A) at ports 1 and 2 was coupled to reduction of sulfate to sulfide (Fig. 4D), indicating SRB activity. Complete sulfide removal required increasing the nitrate concentration to 10 mM, irrespective of whether the inflowing sulfate concentration was 0.75 mM (not shown), 2.0 mM (Fig. 4F), or 6 mM (not shown). The environmental redox potential was high under these conditions (Eh > +200 mV). Nitrate was always depleted at port 1. Its reduction led to residual nitrite only at high nitrate concentrations, depending on the sulfate concentration in the inflowing medium. At 0.013 mM sulfate, nitrite was present at port 1 when the inflowing nitrate concentration was 5, 7.5, or 10 mM (Fig. 4H and I), whereas at 2 mM sulfate, nitrite was present at port 1 only when the inflowing nitrate concentration was 10 mM (Fig. 4C). When lactate was able to reduce both nitrate and sulfate completely (Fig. 4B and E), sulfate removal was slower than nitrate removal. These results prove neither mechanism A or B (Fig. 1). Both result in the net oxidation of lactate with nitrate, and it is difficult to determine from the steady-state profiles whether this is occurring through intermediate sulfur cycling. However, when the inflowing medium contained only 0.013 mM sulfate and 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, or 10.0 mM nitrate, sulfate reduction as part of rapid sulfur cycling is unlikely, since Eh was much higher (−100 < Eh < +100 mV [Fig. 4H and I]) than under conditions of sulfate reduction (Fig. 4D and E) or fermentative metabolism (Fig. 4G), where Eh was less than −300 mV. Hence, direct oxidation of lactate with nitrate (Fig. 1B) occurred under these conditions.

FIG. 4.

Bioreactor profiles of nitrate (□), nitrite (▴), lactate (⧫) and acetate (⋄) concentrations (A to C and G to I) and of Eh (broken lines) (D to F and G to I) and sulfide (•) and sulfate (○) concentrations (D to F). Sulfate concentrations in the inflowing medium were 2 mM (A to F) or 0.013 mM (G to I) with nitrate concentrations of 0, 5, or 10 mM, as indicated. The x axis represents sampling ports 1 to 5 along the length of the column. Port 0 represents the inflowing medium.

Microbial community composition.

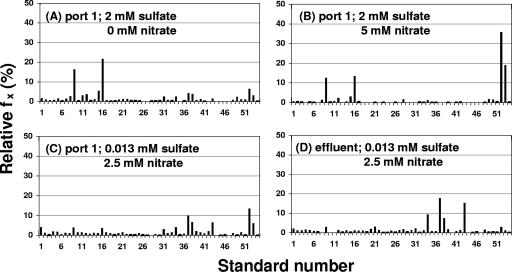

In the presence of 2 mM sulfate, Desulfovibrio sp. strains Lac15 and Lac29 (standards 9 and 16) were major community components (Fig. 5A). Addition of 5 mM nitrate under these conditions boosted the fraction of standards 52 and 53, Sulfurospirillum sp. strains NO2B and KW (Fig. 5B). These were also major community components at 10 mM nitrate both at port 1 and in the column effluent (results not shown), which also contained a high fraction of oil field heterotroph standards 37, 38, and 43 (34). In the presence of 0.75 mM sulfate, there were less SRB than in 2 mM sulfate; strains NO2B and KW remained dominant, and oil field heterotroph standards 34, 37, 38, and 43 were prominent in the effluent both at 5 and 10 mM nitrate (results not shown). Finally, in the presence of 0.013 mM sulfate, SRB were not major community components, confirming direct oxidation of lactate with nitrate under these conditions. Sulfurospirillum sp. strains NO2B and KW were prominent at port 1 (Fig. 5C), but not in the column effluent, which contained primarily oil field heterotroph standards 34, 37, 38, and 43 (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

Microbial community composition in the bioreactor as determined by RSGP. Liquid samples were obtained from port 1 and column effluent with sulfate and nitrate concentrations in the inflowing medium as indicated. fx is the relative fraction of each standard x for which the number is given on the x axis.

Cocultures of SRB and NRB.

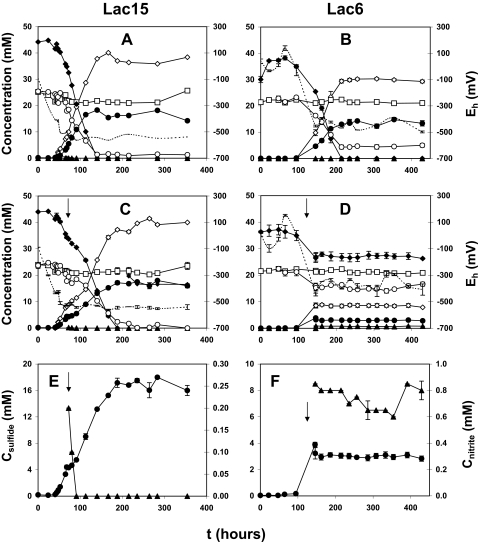

Compared to control cultures (Fig. 6A), sulfate reduction was transiently inhibited following injection of KW into log-phase cultures of strain Lac15 (Fig. 6C). However, nitrate concentrations did not change, and sulfide production resumed once the nitrite concentration, which increased due to injection of KW, was reduced to zero (Fig. 6E). Use of Desulfovibrio sp. strain Lac3 in these experiments gave results similar to those obtained with strain Lac15 (not shown). In contrast, injection of strain KW into log-phase cultures of Desulfovibrio sp. strain Lac6 permanently inhibited sulfate reduction (Fig. 6D) compared to control cultures (Fig. 6B). The constant concentrations of nitrate, sulfide, and nitrite introduced with the KW inoculum (Fig. 6D and F) indicated that strain KW was also metabolically inactive under these conditions. Lac6 cultures turned yellow, indicating the formation of polysulfide.

FIG. 6.

Competitive exclusion of SRB by Sulfurospirillum sp. strain KW. Desulfovibrio sp. strain Lac15 (left panels) and Lac6 (right panels) were grown as pure cultures in CSB-A medium (A and B) or as cocultures with strain KW inoculated during mid-log phase (↓) (C and D). The concentrations of nitrate (□), nitrite (▴), lactate (♦), acetate (⋄), sulfide (•), and sulfate (○) and Eh (broken lines) are shown. Panels E and F show with greater resolution the sulfide (left scale) and nitrite (right scale) concentrations corresponding to panels C and D, respectively. All batch cultures were done in duplicate, with average deviations shown when the error bars exceeded the size of the symbols.

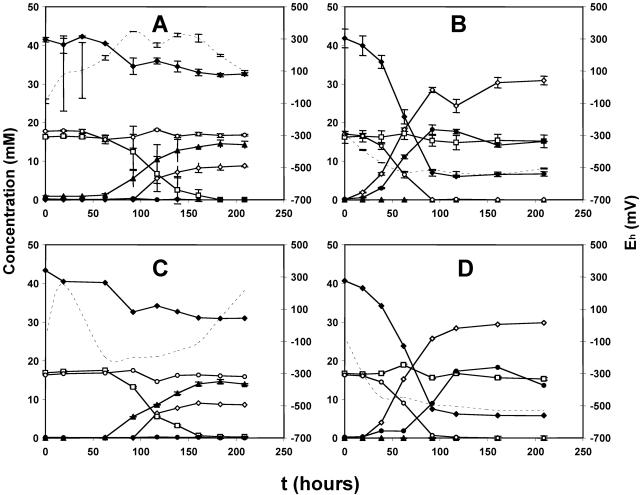

Coinoculation (i.e., both at time zero) of Sulfurospirillum sp. strain KW and Desulfovibrio sp. strain Lac15 or Lac6 into CSB-A medium containing lactate, nitrate, and sulfate, gave hNRB activity and not SRB activity, which was probably suppressed by nitrite (not shown). Use of washed cells eliminated effects of small molecules, like nitrite. Not surprisingly, coinoculation of 7% (vol/vol) strain KW and 2% (vol/vol) of washed strain Lac15 resulted in nitrate reduction in duplicate serum bottles (Fig. 7A). However, when 2% (vol/vol) of strain Lac15 and 7% (vol/vol) of washed strain KW were coinoculated, sulfate reduction occurred in both bottles (Fig. 7B). When washed cells of both strains were coinoculated, nitrate reduction was observed in one serum bottle (Fig. 7C) and sulfate reduction in the other serum bottle (Fig. 7D). Coinjection of strain KW with SRB-free culture filtrate resulted in hNRB activity, whereas coinjection of SRB with KW-free culture filtrate did not result in sulfate reduction (not shown). These results suggest that successful hNRB competition depends on the concentration of nitrite and its ability to inhibit SRB.

FIG. 7.

Effect of using washed cultures on competitive exclusion of Desulfovibrio sp. strain Lac15 and Sulfurospirillum sp. strain KW. The following cultures were coinoculated at time zero: (A) washed Lac15 cells (2% [vol/vol]) and mid-log-phase KW (7% [vol/vol]); (B) mid-log-phase Lac15 (2% [vol/vol]) and washed KW cells (7% [vol/vol]); (C and D) washed Lac15 (2% [vol/vol]) and washed KW (7% [vol/vol]) cells. The concentrations of nitrate (□), nitrite (▴), lactate (♦), acetate (⋄), sulfide (•), and sulfate (○) and Eh (broken lines) are shown. All batch cultures were done in duplicate; average deviations are shown in panels A and B when error bars exceeded the size of the symbols. Panels C and D show duplicate cultures that received similar inocula but gave different results.

DISCUSSION

Nitrate-reducing bacteria can be categorized by their use of organic or inorganic electron donors (hNRB or NR-SOB) and whether nitrate reduction proceeds via denitrification (NO3− → NO2− → NO → N2O → N2) or DNRA (NO3− → NO2− → NH3). The four possible combinations all occur in the Coleville oil field, which was the source for isolating denitrifying hNRB (Thauera sp. strain N2 and Paracoccus sp. strain NO3A), NR-SOB (Thiomicrospira sp. strain CVO), and Sulfurospirillum spp. that couple hNRB or NR-SOB metabolism with DNRA (Fig. 2; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Determining which of the souring control mechanisms (Fig. 1) operate in bioreactor experiments (Fig. 4) is not straightforward, since the dominant Sulfurospirillum spp. (Fig. 5) are capable of either metabolism (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material). Facultative chemolithotrophs, which can grow organotrophically and chemolithotrophically, are thought to have a competitive advantage in environments with organic and inorganic electron donors (17, 30). Indeed we found Sulfurospirillum spp. to dominate in the bioreactor under conditions where both lactate and sulfide were present, whereas strict hNRB, like strains N2 and NO3B, or strict NR-SOB, like strain CVO and Arcobacter sp. strain FWKO_B, were not major components of the community. Coculture experiments using Sulfurospirillum and Desulfovibrio spp. revealed that the former outcompeted the SRB when these could not overcome nitrite inhibition, either because their cell density was too low (12) or because they lacked nitrite reductase (10). Thus, nitrite production appears to be essential for the competitive success of hNRB, whereas nitrite removal is equally essential for the competitive success of SRB when these two groups are competing for a common electron donor in coculture.

Of course, nitrite is only an intermediate in the DNRA by Sulfurospirillum spp. Nitrate-limiting conditions promote ammonia production with little nitrite accumulation in pure cultures of Sulfurospirillum spp. (Fig. 3). This is consistent with the absence of residual nitrite in the bioreactor at lower nitrate doses (Fig. 4B) when nitrate reduction to ammonia was catalyzed by a Sulfurospirillum-dominated community (Fig. 5B). When nitrate is abundant relative to lactate, nitrite is the main product (Fig. 3), and residual nitrite is detected in the bioreactor (Fig. 4C). Relationships similar to those depicted in Fig. 3 have been shown for other NRB, including the denitrifying Thiomicrospira sp. strain CVO (10), and other DNRA-catalyzing organisms (18). Lactate-to-nitrate ratios did not affect the course of lactate oxidation, which always yielded equimolar acetate (Fig. 4; see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), suggesting that oil field Sulfurospirillum spp. are incomplete lactate oxidizers that cannot convert acetate to CO2. When residual sulfide was no longer present in the bioreactor, souring control mainly involved reduction of added nitrate to ammonia, with some nitrite production. Nitrite did not inhibit bioreactor SRB at low nitrate concentrations when the SRB population continued to reduce sulfate. However, nitrite inhibition of SRB contributed to successful competition of hNRB for lactate at higher nitrate concentrations.

The demonstrated dominance of oil field Sulfurospirillum spp. has consequences for understanding nitrate-dependent control of sour petroleum systems. Facultative chemolithotrophy is found among a diverse group of bacteria that includes Achromatium spp., Beggiatoa spp., Paracoccus denitrificans, Thiosphaera pantotropha, and various Thiobacillus spp. (8, 11, 17, 26, 30). However, to our knowledge, this study is the first report of facultative chemolithotropy among the epsilonproteobacteria, a group that is increasingly being recognized in oil field environments (2, 7). Much interest in epsilonproteobacteria has been due to the many NR-SOB in this group and their role in oil field sulfur cycling. Thus, hNRB activity by Sulfurospirillum spp. broadens the potential significance of this phylogenetic group in oil reservoirs. Recent culture-independent community analyses of a Japanese oil storage cavity by Watanabe et al. (37, 38) showed that epsilonproteobacteria were dominant community members. This led to the isolation of the NR-SOB Sulfuricurvum kujiense (19) and to the assumption that sulfur cycling as in Fig. 1A was reducing nitrate in this environment. However, epsilon- and betaproteobacterial clones from the same study were similar to oil field Sulfurospirillum spp. and Thauera sp. strain N2. Hence, hNRB activity by epsilon- and/or betaproteobacteria could also have reduced nitrate and decreased sulfide in the oil storage cavity environment. Souring control by hNRB has been referred to as biocompetitive exclusion (31), suggesting that SRB and hNRB in oil fields share the same substrates. Future investigations into the extent to which reservoir electron donors are shared by SRB and hNRB will improve our understanding of the conditions required for successful application of nitrate to remediate souring.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Strategic Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), by the Alberta Science and Research Authority (ASRA), by ConocoPhillips, and by Baker Petrolite Corporation. C.H. was supported by graduate scholarships from NSERC, the Alberta Ingenuity Fund, and the Government of Alberta.

We thank Pat McCarron and Andrew Richardson from Petrovera Resources for providing water samples produced from the Coleville oil field.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 February 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Microbiol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell, B. J., A. S. Engel, M. L. Porter, and K. Takai. 2006. The versatile ɛ-proteobacteria: key players in sulfidic habitats. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:458-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cord-Ruwisch, R. A. 1985. A quick method for determination of dissolved and precipitated sulfides in cultures of sulfate reducing bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 4:33-36. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenmann, E., J. Beuerle, K. Sulger, P. M. H. Kroneck, and W. Schumacher. 1995. Lithotrophic growth of Sulfurospirillum deleyianum with sulfide as electron donor coupled to respiratory reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Arch. Microbiol. 164:180-185. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gevertz, D., A. J. Telang, G. Voordouw, and G. E. Jenneman. 2000. Isolation and characterization of strains CVO and FWKO B, two novel nitrate-reducing, sulfide-oxidizing bacteria isolated from oil field brine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2491-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gieg, L. M., E. A. Greene, D. L. Coy, and P. M. Fedorak. 1998. Diisopropanolamine biodegradation potential at sour gas plants. Ground Water Monit. Remediation 18:158-173. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grabowski, A., O. Nercessian, F. Fayolle, D. Blanchet, and C. Jeanthon. 2005. Microbial diversity in production waters of a low-temperature biodegraded oil reservoir. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 54:427-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray, N. D., R. Howarth, R. W. Pickup, J. Gwyn Jones, and I. M. Head. 2000. Use of combined microautoradiography and fluorescence in situ hybridization to determine carbon metabolism in mixed natural communities of uncultured bacteria from the genus Achromatium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4518-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg, A. E., L. S. Clesceri, and A. D. Eaton (ed.). 1992. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 18th ed., p. 439-440. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC.

- 10.Greene, E. A., C. Hubert, M. Nemati, G. Jenneman, and G. Voordouw. 2003. Nitrite reductase activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria prevents their inhibition by nitrate-reducing, sulfide-oxidizing bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 5:607-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagen, K. D., and D. C. Nelson. 1996. Organic carbon utilization by obligately and facultatively autotrophic Beggiatoa strains in homogeneous and gradient cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:947-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haveman, S. A., E. A. Greene, C. P. Stilwell, J. K. Voordouw, and G. Voordouw. 2004. Physiological and gene expression analysis of inhibition of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough by nitrite. J. Bacteriol. 186:7944-7950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks, R. E., R. I. Amann, and D. A. Stahl. 1992. Dual staining of natural bacterioplankton with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and fluorescent oligonucleotide probes targeting kingdom-level 16S rRNA sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2158-2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiraishi, A., K. Muramatsu, and Y. Ueda. 1996. Molecular genetic analyses of Rhodobacter azotoformans sp. nov. and related species of phototrophic bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 19:168-177. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubert, C., M. Nemati, G. Jenneman, and G. Voordouw. 2005. Corrosion risk associated with microbial souring control using nitrate or nitrite. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 68:272-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hubert, C., M. Nemati, G. Jenneman, and G. Voordouw. 2003. Containment of biogenic sulfide production in continuous up-flow packed-bed bioreactors with nitrate or nitrite. Biotechnol. Prog. 19:338-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Hubert, C., G. Voordouw, J. Arensdorf, and G. E. Jenneman. 2006. Control of souring through a novel class of bacteria that oxidize sulfide as well as oil organics with nitrate, paper 06669. In Corrosion/2006. NACE International, Houston, TX.

- 17.Kelly, D. P. 1992. The chemolithotrophic prokaryotes, p. 331-343. In A. Balows, H. G. Trüper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K.-H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes. A handbook on the biology of bacteria: ecophysiology, isolation, identification, applications, vol. 1. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelso, B. H., R. V. Smith, R. J. Laughlin, and S. D. Lennox. 1997. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction in anaerobic sediments leading to river nitrite accumulation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4679-4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodama, Y., and K. Watanabe. 2003. Isolation and characterization of a sulfur-oxidizing chemolithotroph growing on crude oil under anaerobic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:107-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen, J., M. H. Rod, and S. Zwolle. 2004. Prevention of reservoir souring in the Halfdan field by nitrate injection, paper 04761. In Corrosion/2004. NACE International, Houston, TX.

- 21.Larsen, J. 2002. Downhole nitrate applications to control sulfate-reducing bacteria activity and reservoir souring, paper 02025. In Corrosion/2002. NACE International, Houston, TX.

- 22.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, R. Westram, L. Richter, H. Meier, Yadhukumar, A. Buchner, T. Lai, S. Steppi, G. Jobb, W. Förster, I. Brettske, S. Gerber, A. W. Ginhart, O. Gross, S. Grumann, S. Hermann, R. Jost, A. König, T. Liss, R. Lüssmann, M. May, B. Nonhoff, B. Reichel, R. Strehlow, A. Stamatakis, N. Stuckmann, A. Vilbig, M. Lenke, T. Ludwig, A. Bode, and K.-H. Schleifer. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myhr, S., B.-L. Lillebø, E. Sunde, J. Beeder, and T. Torsvik. 2002. Inhibition of H2S producing hydrocarbon degrading bacteria in an oil reservoir model column by nitrate injection. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58:400-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nemati, M., G. E. Jenneman, and G. Voordouw. 2001. Mechanistic study of microbial control of hydrogen sulfide production in oil reservoirs. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 74:424-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemati, M., T. Mazutinec, G. E. Jenneman, and G. Voordouw. 2001. Control of biogenic H2S production by nitrite and molybdate. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26:350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh, S. E., Y. B. Yoo, J. C. Young, and I. S. Kim. 2001. Effect of organics on sulfur-utilizing autotrophic denitrification under mixotrophic conditions. J. Biotechnol. 92:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen, G. J., D. J. Lane, S. J. Giovannoni, N. R. Pace, and D. A. Stahl. 1986. Microbial ecology and evolution: a ribosomal RNA approach. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 40:337-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philipp, B., and B. Schink. 2000. Two distinct pathways for anaerobic degradation of aromatic compounds in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica strain AR-1. Arch. Microbiol. 173:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinsel, M. A., J. T. Sears, P. S. Stewart, and M. J. McInerney. 1996. Control of microbial souring by nitrate, nitrite or glutaraldehyde injection in a sandstone column. J. Ind. Microbiol. 17:128-136. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson, L. A., and J. G. Kuenen. 1983. Thiosphaera pantotropha gen. nov. sp. nov., a facultatively anaerobic, facultatively autotrophic sulphur bacterium. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129:2847-2855. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandbeck, K. A., and D. O. Hitzman. 1995. Biocompetitive exclusion technology: a field system to control reservoir souring and increase production, p. 311-320. In R. Byrant and K. L. Sublette (ed.), Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery and Related Biotechnology for Solving Environmental Problems. National Technical and Information Services, Springfield, VA.

- 32.Saraiva, L. M., P. N. da Costa, C. Conte, A. V. Xavier, and J. LeGall. 2001. In the facultative sulphate/nitrate reducer Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 27774, the nine-haem cytochrome c is part of a membrane-bound redox complex mainly expressed in sulphate-grown cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1520:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snell, F. D., and C. T. Snell. 1949. Colorimetric methods of analysis. D. van Nostrand, New York, NY.

- 34.Telang, A. J., S. Ebert, J. M. Foght, D. W. S. Westlake, G. E. Jenneman, D. Gevertz, and G. Voordouw. 1997. The effect of nitrate injection on the microbial community in an oil field as monitored by reverse sample genome probing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1785-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorstenson, T., G. Bødtker, E. Sunde, and J. Beeder. 2002. Biocide replacement by nitrate in sea water injection systems, paper 02033. In Corrosion/2002. NACE International, Houston, TX.

- 36.Voordouw, G., S. M. Armstrong, M. F. Reimer, B. Fouts, A. J. Telang, Y. Shen, and D. Gevertz. 1996. Characterization of 16S rRNA genes from oil field microbial communities indicates the presence of a variety of sulfate-reducing, fermentative, and sulfide-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1623-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe, K., K. Watanabe, Y. Kodama, K. Syutsubo, and S. Harayama. 2000. Molecular characterization of bacterial populations in petroleum- contaminated groundwater discharged from underground crude oil storage cavities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4803-4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe, K., Y. Kodama, and N. Kaku. 2002. Diversity and abundance of bacteria in an underground oil-storage cavity. BMC Microbiol. 2:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]