Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni isolates possess multiple adhesive proteins termed adhesins, which promote the organism's attachment to epithelial cells. Based on the proposal that one or more adhesins are shared among C. jejuni isolates, we hypothesized that C. jejuni strains would compete for intestinal and cecal colonization in broiler chicks. To test this hypothesis, we selected two C. jejuni strains with unique SmaI pulsed-field gel electrophoresis macrorestriction profiles and generated one nalidixic acid-resistant strain (the F38011 Nalr strain) and one streptomycin-resistant strain (the 02-833L Strr strain). In vitro binding assays revealed that the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains adhered to LMH chicken hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells and that neither strain influenced the binding potential of the other strain at low inoculation doses. However, an increase in the dose of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain relative to that of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain competitively inhibited the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to LMH cells in a dose-dependent fashion. Similarly, the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain was found to significantly reduce the efficiency of intestinal and cecal colonization by the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain in broiler chickens. Based on the number of bacteria recovered from the ceca, the maximum number of bacteria that can colonize the digestive tracts of chickens may be limited by host constraints. Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that C. jejuni strains compete for colonization in chicks and suggest that it may be possible to design novel intervention strategies for reducing the level at which C. jejuni colonizes the cecum.

Campylobacter jejuni is a gram-negative, microaerophilic, spiral-shaped, motile bacterium. While a number of species within the genus Campylobacter are associated with enteritis (1, 12, 17, 33), C. jejuni is the most common bacterial cause of food-borne, diarrheal disease in the United States. Campylobacter enteritis, or campylobacteriosis, commonly results 1 to 7 days after ingestion of as few as 500 organisms (31) and is characterized by a rapid onset of fever, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. Stool samples from C. jejuni-infected individuals frequently contain cellular exudate, pus or mucus, and leukocytes. Mucosal ulcerations and crypt abscesses have been observed in C. jejuni-infected individuals (19). While the disease is most often self-limiting (2 to 7 days), individuals suffering from severe campylobacteriosis can be treated with erythromycin or ciprofloxacin. Certain strains of C. jejuni have been implicated as an antecedent to the development of Guillain-Barré syndrome or acute postinfectious polyneuritis (9, 18, 30, 38). Guillain-Barré syndrome is the most common cause of acute neuromuscular paralysis (9).

Most cases of campylobacteriosis are sporadic in nature. Epidemiological case studies, which have been performed to identify the risk factors associated with sporadic cases of human campylobacteriosis, have demonstrated a link between C. jejuni-mediated enteritis and the handling and consuming of raw or undercooked poultry meats. This linkage is due largely to the fact that, by 2 to 3 weeks of age, most commercially reared poultry are colonized by C. jejuni (7). Investigations have also revealed that 50 to 90% of domestic-chicken carcasses are contaminated at the time of sale (3, 35). Despite the link between human infections with C. jejuni and the handling of raw chicken, our understanding of C. jejuni physiology and behavior in a natural host (chickens) is in its infancy and intervention/control methods (e.g., vaccines or colonization-blocking strategies) for reducing the number of cases of human campylobacteriosis are nonexistent.

Bacterial adhesins are defined as proteins that facilitate the binding of bacteria to host cells. To date, all the molecules proposed to act as adhesins are synthesized constitutively by C. jejuni. This fact is consistent with early studies in which metabolically inactive (heat-killed and sodium azide-killed) C. jejuni bacteria were found to bind to cultured cells at levels equivalent to those for metabolically active organisms (14). The best-characterized C. jejuni adhesins include the 37-kDa outer membrane protein termed CadF (Campylobacter adhesion to fibronectin [Fn]) (13, 15, 16, 22, 23, 39), a 42.3-kDa lipoprotein termed JlpA (jejuni lipoprotein A) (8), and a 28-kDa periplasmic/membrane-associated protein termed PEB1 (28). Other C. jejuni molecules that may act as adhesins include the flagellin proteins, lipopolysaccharide (20, 25), the major outer membrane protein PorA (24, 32), and P95 (10).

The ability of C. jejuni to adhere to epithelial cells lining the gastrointestinal tracts of humans is proposed to be an important virulence attribute (2, 4, 8, 10, 11, 15, 24-27, 32). This proposal is supported by data indicating that C. jejuni isolates recovered from individuals with fever and diarrhea adhere to cultured cells in greater numbers than isolates from asymptomatic individuals (5). Likewise, the ability of C. jejuni to bind to receptors on cells lining the intestinal tracts of birds appears to be required for colonization. In contrast to a C. jejuni F38011 wild-type isolate, the C. jejuni cadF mutant is unable to colonize the intestinal tracts of Leghorn chickens (39). Consequently, in vitro adherence assays have been used extensively to characterize the interactions of C. jejuni with host cells and to attempt to identify the bacterial molecules that mediate host cell binding.

Understanding how C. jejuni colonizes poultry is important for developing successful approaches for reducing or eliminating C. jejuni carriage. While the ability of C. jejuni to colonize the digestive tract of a chick is clearly multifactorial, our working hypothesis is that C. jejuni constitutively synthesizes a subset of adhesive proteins that facilitate the organism's binding to the cells lining the intestinal tracts of chickens. If this is correct, then C. jejuni strains should compete for colonization of broiler chicks. Moreover, once a strain has colonized, it should have a competitive advantage in the host and impede the ability of a second strain to colonize. In this study, we performed in vitro and in vivo adherence and colonization assays with one C. jejuni clinical strain (F38011) and a second C. jejuni strain recovered from a chicken (02-833L) to gain a better understanding of bacterium-host cell interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of bacterial strains.

C. jejuni F38011 was isolated from a human with bloody diarrhea, whereas the C. jejuni strains 02-833L and CS were isolated from chicken carcasses. The C. jejuni F38011, 02-833L, and CS strains used in this study were passaged fewer than 10 times after initial isolation. The C. jejuni strains were cultured under microaerobic conditions on Mueller-Hinton agar plates supplemented with 5% citrated bovine blood (MH-blood agar plates) at 37°C. Cultures were subcultured to a fresh plate every 24 to 48 h. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 85-102840 was cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates at 37°C.

Selection of C. jejuni strains resistant to antibiotics.

To generate antibiotic-resistant strains of C. jejuni for use in further assays, one loopful of wild-type bacteria cultured on MH-blood agar was spread on an MH-blood agar plate supplemented with either 50 μg/ml nalidixic acid for F38011 or 20 μg/ml streptomycin for 02-833L. The antibiotic plates were incubated under microaerobic conditions, resistant colonies were picked, and motility was confirmed before use in this study.

Bacterial growth assays.

Growth assays were performed using the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strains. In these experiments, bacteria were inoculated in MH broth to an optical density at 540 nm (OD540) of 0.02 and incubated under microaerobic conditions with constant shaking (60 rpm) at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at the indicated intervals for enumeration. Numbers of viable bacteria were determined by plating serial dilutions of the bacterial suspensions and counting the resultant colonies. The resulting CFU values were log transformed and plotted versus time to determine the slope at the exponential growth phase and to calculate the specific growth rate and doubling time.

Motility assay.

Motility assays were performed using MH medium supplemented with 0.4% select agar (Life Technologies, United Kingdom). Briefly, 10 μl of a bacterial suspension was added to the center of a plate, after which the plate was incubated at 37°C under microaerobic conditions for 48 h.

Culture of LMH cells.

LMH chicken hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells (ATCC CRL-2117) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Stock cultures of LMH cells were grown in flasks coated with 0.1% gelatin in Waymouth's MB 752/1 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

C. jejuni-LMH cell binding assay.

For the adherence assays, a 24-well tissue culture tray was seeded with 1.5 × 105 LMH cells/well and cells were incubated for 18 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were rinsed with Waymouth's MB 752/1 medium supplemented with 1% FBS (Waymouth's medium-1% FBS). Unless otherwise stated, the LMH cells were inoculated with approximately 2.5 × 107 CFU of the C. jejuni F38011 and C. jejuni 02-833L strains suspended in Waymouth's medium-1% FBS. Bacterium-host cell contact was promoted by centrifugation at 600 × g for 5 min. Following a 30-min incubation at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator, the epithelial cells were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove nonadherent bacteria. The epithelial cells were then lysed with a solution of 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. The suspensions were serially diluted and the number of viable, adherent bacteria determined by counting the resultant colonies on MH-blood agar plates. The values reported represent the mean counts ± standard deviations derived from triplicate wells. Significance between samples was determined with Student's t test following log10 transformation of the data. Two-tailed P values were determined for each sample, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

IF microscopy.

Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of C. jejuni-LMH cell binding was performed using methods described previously (23). LMH cells (7.5 × 104 cells/well) were cultured on 13-mm circular glass coverslips for 18 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were inoculated with 5 × 106 CFU of C. jejuni in 0.5 ml of Waymouth's medium-1% FBS. After 30 min of incubation, the inoculated cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. The LMH cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. To detect cell-associated bacteria, the samples were incubated for 45 min at an ambient temperature with a rabbit anti-C. jejuni antibody prepared against Campylobacter whole-cell lysates, followed by a second incubation for 45 min at an ambient temperature with a 1:500 dilution of a Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA). Actin was stained using tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 0.2 μg/ml. Coverslips were mounted on Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain the nucleus. The samples were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 inverted epifluorescence microscope. Images were captured using the imaging software MetaMorph version 5 and processed using Adobe Photoshop 3.0.4.

RNA isolation.

Campylobacter strains were grown to exponential phase (A540 = 0.8) under microaerobic conditions with constant shaking (60 rpm) at 37°C in MH medium. RNA degradation was inhibited by addition of 1/10 volume of stop solution (10% phenol in ethanol), and the cultures were rapidly cooled in an ice water bath. Immediately, duplicate 2.8-ml samples (two OD540 equivalents) for each culture were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 1 min at 4°C. Total RNA was isolated as described by Syn et al. (36) with the following modifications. The pellet was suspended in 710 μl of STT buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% Tween 20, 1% Triton X-100) and then acidified with 20 μl 1 M HCl and 70 μl 2 M sodium acetate (pH 4.0). The cell lysates were extracted with shaking at room temperature three times with 500 μl of citrate-buffered phenol (pH 4.0)-chloroform (4:1) and twice with 500 μl chloroform. The samples were isopropanol precipitated, washed with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in RNase-free water before two DNase treatments (RQ1 DNase; Promega, Madison, WI).

RT and real-time quantitative PCR.

Reverse transcription (RT) of 1 μg of total RNA was carried out in a 20-μl total volume with ThermoScript reverse transcriptase according to the supplier's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Thermal reaction conditions were as follows: preheating of the RNA sample for 5 min at 65°C, adding of the reaction mixture on ice, heating for 50 min at 50°C and 5 min at 85°C for enzyme denaturation, and rapid cooling to 4°C.

Gene quantification was performed on the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time quantitative PCR was carried out with 0.1 μl of a cDNA template and 300 nM of each primer in duplicate 25-μl reaction mixtures with Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). RNA samples without a reverse transcriptase step (to identify background due to genomic DNA contamination) were included for every sample and primer combination. Thermal-cycling conditions were as follows: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 repeats of 15 s at 95°C, and 1 min at 55°C. PCR efficiencies were determined from standard curves of cDNA dilutions and their respective cycle thresholds. To correct for variance in mRNA template concentration and efficiency of the RT reaction, the cadF gene was chosen as a reference gene. The results are presented as ratios of gene expression between the target gene and the reference gene (29).

Broiler chickens.

Sixty chickens were subdivided into six groups of 10 chicks; the chicks were then placed into isolation chambers (Horsfall Bauer isolators) on wire mesh. Water and a commercial chick starter feed were provided ad libitum. Each isolator was equipped with two removable metal trays. Fecal matter was collected and autoclaved before disposal. All animal studies were performed using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; protocol no. 3248) at Washington State University.

Campylobacter cultures and chicken inoculation.

The C. jejuni F38011 and 02-833L strains were cultured in Bolton's broth at 42°C for 16 h under microaerobic conditions (85% nitrogen, 10% CO2, 5% oxygen) prior to inoculation of 9-day-old chicks by oral gavage with 0.5 ml of a bacterial suspension (∼107 bacteria). One group of 10 chickens was kept as the uninoculated control group. The remaining five groups of chicks were inoculated with the following: group 2, the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain only; group 3, the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain only; group 4, equal doses of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strains; group 5, the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain, followed by inoculation with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain 1 week later; and group 6, the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain, followed by inoculation with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain 1 week later. After the chickens were inoculated, each of the remaining bacterial suspensions was serially diluted and plated onto cefoperazone-vancomycin-amphotericin B agar to confirm the number of CFU in each dose.

Campylobacter enumeration.

All 10 chickens in each group were euthanized and necropsied at 14 days postinoculation (dpi). Two methods were used for C. jejuni enumeration. The first method involved selective enrichment and endpoint growth analysis. A 4- to 5-in.-long section of the intestine, distal to the duodenal loop, and a same-length segment of the mid-intestine were dissected from each chicken and tested as a composite intestine sample for Campylobacter organisms. A cecum was dissected from each chicken and similarly tested. The samples were weighed and diluted 1:10 (weight/volume) in Bolton's broth media and thoroughly stomached. For enumeration, serial 10-fold dilutions were made in 3-ml quantities of Bolton's broth media in 5-ml tubes to determine the dilution at which the C. jejuni strains would not grow. The samples were diluted in tubes and incubated in a microaerobic environment. The diluted cultures were incubated at 42°C for 16 to 20 h and plated the next day onto either cefoperazone-vancomycin-amphotericin B agar plates (uninoculated chicks), MH-blood agar plates supplemented with nalidixic acid to determine the number of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria, or MH-blood agar plates supplemented with streptomycin sulfate to determine the number of C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria. The agar plates were again incubated in a microaerobic environment at 42°C and CFU counted after 48 h of incubation. The second Campylobacter enumeration method involved direct plating of the composite intestine and cecum samples on the appropriate media immediately after each sample was thoroughly stomached in Bolton's broth.

Macrorestriction enzyme profile pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

C. jejuni bacteria were harvested from MH-blood agar plates in 1 ml of PBS and cell densities adjusted to 0.75 to 0.80 using a Microscan turbidity meter (Dade Behring, West Sacramento, CA). Four hundred microliters of 1.4% (wt/vol) molten (50°C) pulsed-field-grade agarose (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was added to an equivalent volume of each bacterial suspension and mixed gently, and a 100-μl aliquot was pipetted into agarose plug molds. After setting, the agarose plugs were removed from the molds and incubated in 1 ml of ESP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM EDTA, 1% [wt/vol] N-lauroyl sarcosine, 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K) at 53°C for 1 h. The agarose plugs were then washed two times in PBS at 53°C, two times in PBS at an ambient temperature, and once in sterile water at an ambient temperature. Individual agarose plugs were incubated with 100 μl of restriction endonuclease buffer containing 20 U of SmaI at 25°C for 4 h. Restricted genomic DNA was separated in 1% (wt/vol) pulsed-field-grade agarose that had been prepared with 0.5× TBE (0.089 M Tris base, 0.089 M boric acid, 0.002 M EDTA [pH 8.0]). Samples were electrophoresed for 19 h at 120 V and 14°C with a reorientation angle of 120 degrees and a ramped pulse time of 6.8 to 35.4 s. Gels were stained for 20 min in 3 μg/ml ethidium bromide and destained for 20 min in water. Images were captured using a Bio-Rad FluorS system and processed using Adobe Photoshop.

RESULTS

C. jejuni F38011 and 02-833L motility and growth characteristics.

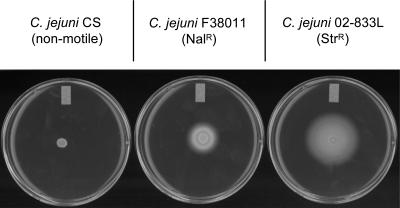

C. jejuni F38011 and C. jejuni 02-833L were chosen for this study as previous work indicated that both isolates effectively colonize chickens. We isolated a C. jejuni F38011 nalidixic acid-resistant (Nalr) isolate and a C. jejuni 02-833L streptomycin-resistant (Strr) isolate and confirmed the motility of each isolate on MH medium supplemented with 0.4% agar (Fig. 1). Although both the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strains were motile, the zone of bacterial migration was consistently larger for the 02-833L Strr strain than for the F38011 Nalr strain.

FIG. 1.

Assessment of C. jejuni motility on MH medium supplemented with 0.4% agar. C. jejuni F38011 was isolated from a human with bloody diarrhea, and C. jejuni 02-833L was isolated from the carcass of a chicken. The C. jejuni CS strain, which was recovered from a chick, is a naturally occurring nonmotile isolate. Exponential-phase cultures were inoculated to motility plates and incubated as described in Materials and Methods.

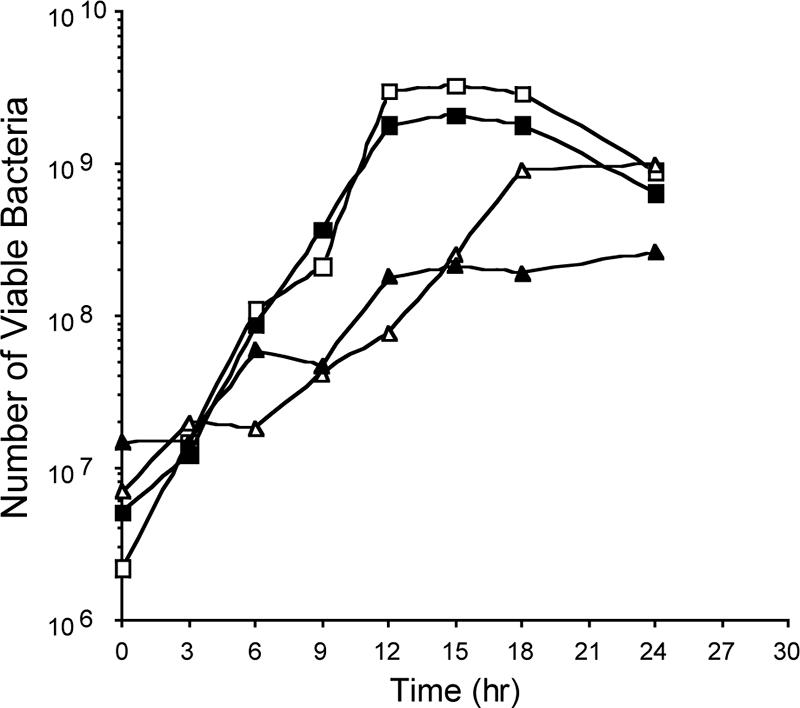

Growth experiments were performed with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains to determine the growth rate of each organism and to ensure that each strain could be recovered from a mixed culture (Fig. 2). Based on three independent experiments, the growth curves revealed the doubling time of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to be 90 min, with a standard deviation of 18 min, and the doubling time of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain to be 180 min, with a standard deviation of 12 min. When the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains were mixed together, a decrease was noted in the growth rate of the 02-833L Strr strain. In the mixed culture, the doubling time of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain was 90 min, with a standard deviation of 13 min, and the growth rate of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain was 294 min, with a standard deviation of 72 min. Although the growth rate of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain decreased from 180 min to 294 min when the strain was cultured alone versus with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain, this difference was not statistically significant. In addition, the viabilities of both strains appeared to plateau at approximately the same level within 24 h of the maximum viable CFU/ml. Apparent from these experiments was that the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains could be readily recovered from a mixed culture based on their antibiotic resistances.

FIG. 2.

Representative growth curves of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains. MH broth was inoculated with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains at an OD540 of 0.02 and incubated under microaerobic conditions with constant shaking (60 rpm) at 37°C. Cultures are indicated as follows: C. jejuni F38011 Nalr alone (open squares), C. jejuni 02-833L Strr alone (open triangles), and C. jejuni F38011 Nalr (closed squares) cocultured with C. jejuni 02-833L Strr (closed triangles).

Expression of C. jejuni F38011 and 02-833L adhesins.

Previous work has demonstrated that the CadF protein is necessary for C. jejuni to colonize chickens (39). Given the host cell binding differences in the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains, we assessed whether these strains expressed known and putative adhesins by real-time RT-PCR (data not shown). Based on real-time RT-PCR analysis, no significant differences were detected in the cadF, jlpA, porA, and peb1 transcripts between the two strains. However, the amounts of transcript differed among the genes within each strain (i.e., the expression levels, from highest to lowest, were those of porA, cadF, peb1, and jlpA). Consistent with previous work, these data suggest that the C. jejuni genes that encode known and putative adhesins are expressed constitutively (14).

Characteristics of binding of C. jejuni F38011 and C. jejuni 02-833L to LMH cells.

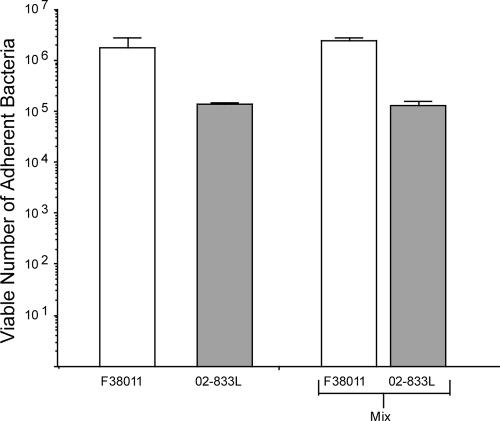

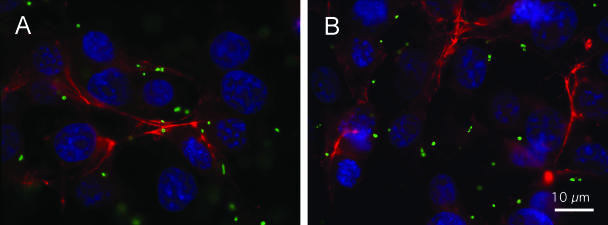

In vitro adherence assays have been used extensively to characterize the interactions of C. jejuni with host mammalian cells as investigators have proposed that these assays are indicative of the organism's virulence potential (5). To determine the binding potential of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains, in vitro adherence assays were performed. To minimize motility-dependent effects and to synchronize the infection, bacterium-host cell contact was promoted by a centrifugation step. In preliminary assays performed with both INT 407 human epithelial cells and LMH chicken hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells, differences were not observed in the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to these epithelial cells (not shown). In addition, no differences were observed in the binding of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain to the INT 407 and LMH epithelial cells (not shown). Because additional experiments that involved assessing the colonization potential of the C. jejuni strains in chickens were planned, we proceeded with the LMH cells. We observed a greater number of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria bound to the LMH cells than was observed with the 02-833L Strr bacterial strain (Fig. 3). Moreover, the binding potential of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain relative to that of the 02-833L Strr strain was greater regardless of the inoculation doses (not shown). In addition, the number of bacteria bound to LMH cells did not change significantly when strains were inoculated individually or in combination (Fig. 3, Mix). IF microscopy examination of the C. jejuni-inoculated LMH cells revealed similar binding patterns for the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains (Fig. 4). Both bacterial strains appeared to bind to the peripheries of the LMH cells.

FIG. 3.

Adherence of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains to LMH chicken hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells. Binding assays were performed as outlined in Materials and Methods, with a 5.0 × 107-CFU inoculum of each strain. “Mix” refers to LMH cells inoculated with equal doses of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains. Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation for C. jejuni F38011 Nalr (open bars) and C. jejuni 02-833L Strr (gray bars) bound to the LMH cells per well of a 24-well plate. The difference in binding between strains for the mixed inoculation was determined to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

FIG. 4.

IF microscopy showing the peripheral association of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr (A) and 02-833L Strr (B) strains to LMH chicken hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells. LMH cell-associated C. jejuni bacteria were stained with a rabbit anti-C. jejuni antibody, followed by incubation with a Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody. Actin (red staining) was stained using tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI.

Competitive inhibition of binding of C. jejuni F38011 to LMH cells with C. jejuni 02-833L.

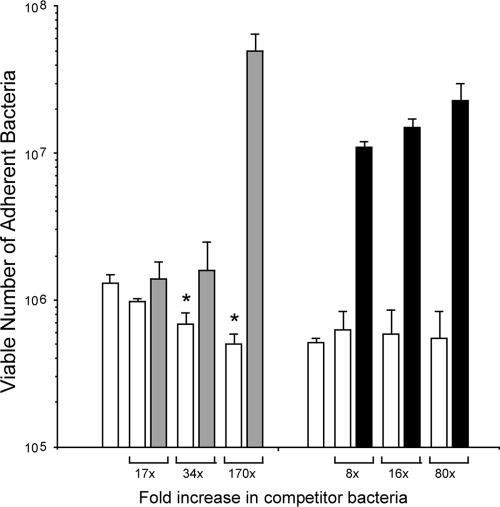

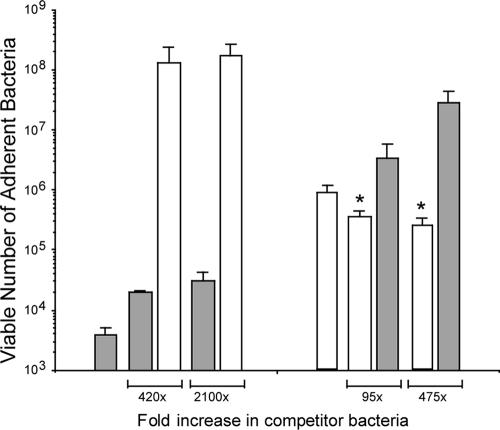

Because the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains expressed the cadF, jlpA, porA, and peb1 transcripts at similar levels, experiments were performed to determine if the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to LMH cells could competitively inhibit the binding of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain to cells (Fig. 5). For these experiments, the LMH cells were inoculated with a constant number of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria and variable numbers of bacteria of the potential competitor strains, either the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain or S. enterica serovar Typhimurium 85-102840. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium 85-102840 was included in these experiments as a negative control as we expected that the salmonella and campylobacter strains would bind to different host cell receptors. The C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain competitively inhibited the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to LMH cells, resulting in an approximately threefold reduction in binding by the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain in the presence of a 170-fold excess of C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria. This inhibition of binding was judged to be specific because the effect was dose dependent (i.e., the greater the increase in the dose of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain relative to that of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain, the greater the inhibition of the binding of F38011 to the LMH cells) and this effect was not observed with the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium 85-102840 strain.

FIG. 5.

Competitive inhibition of the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to LMH chicken hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain. Binding assays were performed as outlined in Materials and Methods, with a 1.7 × 107-CFU inoculum of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain. A 2.9 × 109-CFU inoculum of C. jejuni 02-833L Strr represents a 170-fold increase for the competitor strain. Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation for C. jejuni F38011 Nalr (open bars), C. jejuni 02-833L Strr (gray bars), and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (filled bars) bound to the LMH cells per well of a 24-well plate. An asterisk indicates that the value is significantly different from that of the control (P < 0.05).

To test whether the binding of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain to LMH cells could be inhibited with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain, we performed additional experiments in which C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria were maintained at constant numbers and excesses of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria were added (Fig. 6). We again observed that the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain competitively inhibited the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to LMH cells. However, an excess of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria did not reduce the binding of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain to LMH cells. Even when C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria were present at a 2,100-fold excess relative to C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria, no difference was observed in the number of 02-833L Strr bacteria bound to the LMH cells compared to that in the control (i.e., cells inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain in the absence of a competitor).

FIG. 6.

Excess C. jejuni 02-833L Strr reduces the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to LMH cells, but an excess in the number of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria does not reduce the binding of C. jejuni 02-833L Strr to LMH cells. Binding assays were performed as outlined in Materials and Methods. In the left panel, a constant-level inoculation with 2.0 × 106 CFU of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain was challenged with up to 4.2 × 109 CFU of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain, representing a 2,100-fold increase for the competitor strain. In the right panel, a constant-level inoculation with 4.2 × 106 CFU of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain was challenged with up to 2.0 × 109 CFU of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain, representing a 475-fold increase for the competitor strain. Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation for C. jejuni F38011 Nalr (open bars) and C. jejuni 02-833L Strr (gray bars) bound to the LMH cells per well of a 24-well plate. An asterisk indicates that the value is significantly different from that of the control (P < 0.05).

C. jejuni 02-833L reduces the colonization efficiency of C. jejuni F38011 in broiler chicks.

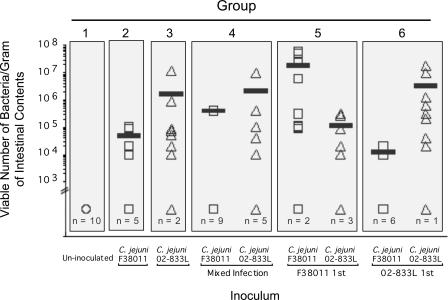

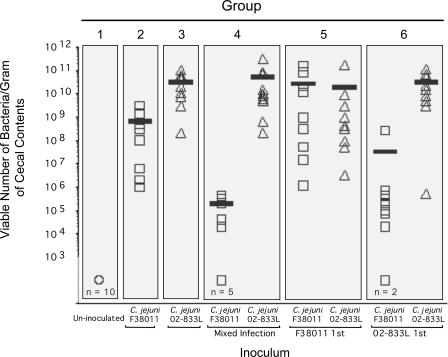

To determine whether colonization with one C. jejuni strain would affect the ability of a second C. jejuni strain to colonize chickens, 60 chickens were divided into six groups, each consisting of 10 birds. Group 1 was the uninoculated control group, group 2 was inoculated with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain only, group 3 was inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain only, group 4 was inoculated with equal doses of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strains at the same time, group 5 was inoculated with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain and 1 week later inoculated with an equivalent dose of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain, and group 6 was inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain and 1 week later inoculated with an equivalent dose of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain. All chickens were euthanized at 14 dpi and the number of C. jejuni bacteria quantitated from a composite intestinal sample and a cecal sample from each bird. Two different methods were used to determine the number of C. jejuni bacteria in a sample; one method involved selective enrichment of the prepared samples coupled with endpoint growth analysis, and the second method involved direct plating of the prepared samples. Because the two methods of C. jejuni enumeration yielded similar results, only the results obtained for the direct-plating method are shown (Fig. 7 and 8). The numbers of bacteria recovered per gram of intestinal contents were found to differ within a group of chickens inoculated with a particular strain (Fig. 7). In contrast, the numbers of bacteria recovered per gram of cecal contents yielded more consistent results (Fig. 8). Thus, the following discussion pertains to the trends observed in the recovery of bacteria from the cecal contents. C. jejuni bacteria were not recovered from any of the uninoculated chickens (group 1). In addition, C. jejuni bacteria were recovered from the cecal contents of 10 of 10 chickens inoculated with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain only (group 2), and the same was true for chickens inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain only (group 3). However, inoculating the chickens with both C. jejuni strains, either simultaneously or in a sequence, resulted in dramatic changes in the efficiency of colonization by one strain or the other. Most obvious were the differences noted in the colonization of chickens inoculated with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain when the birds were inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain at the same time (group 4) as well as when the birds were inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain 1 week prior to inoculation with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain (group 6). In both instances, the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain did not colonize more than half of the birds in the groups (i.e., in group 4, the F38011 Nalr strain was not recovered from the ceca of five birds; in group 6, the F38011 Nalr strain was not recovered from the ceca of six birds). The inoculation of the birds with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain prior to inoculation with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain did not have a statistically significant effect on C. jejuni 02-833L Strr cecal colonization (group 5). However, the numbers of C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria recovered from the ceca of the birds in group 5 were more variable than those from birds inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain only (group 3) or birds inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain followed by the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain (group 6). In general, the birds that harbored fewer C. jejuni bacteria in the cecum also contained fewer C. jejuni bacteria in the intestine than highly colonized birds (or none). Overall, these data indicate that one strain of C. jejuni can have a significant effect on the ability of a second C. jejuni strain to colonize the digestive tracts of chickens, but the amplitude of the effect differs depending on the strains and whether colonization has been established before exposure to a second strain.

FIG. 7.

C. jejuni 02-833L reduces the efficiency of intestinal colonization by C. jejuni F38011 in broiler chicks. C. jejuni F38011 and C. jejuni 02-833L were recovered from the intestinal tracts of chicks at 14 dpi as outlined in Materials and Methods. The circle indicates uninoculated chicks. Each square indicates the number of viable C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria recovered from a pooled intestinal sample. Each triangle indicates the number of viable C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria recovered from a pooled intestinal sample. n indicates the number of birds in the group of 10 from which no viable C. jejuni bacteria were recovered (limit of detection, 103 CFU/gram intestinal contents). The bar indicates the mean number of bacteria that were recovered from only those birds that were colonized with C. jejuni.

FIG. 8.

C. jejuni 02-833L reduces the efficiency of cecal colonization by C. jejuni F38011 in broiler chicks. C. jejuni F38011 and C. jejuni 02-833L were recovered from the ceca of chicks at 14 dpi as outlined in Materials and Methods. The circle indicates uninoculated chicks. Each square indicates the number of viable C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria recovered from a cecum. Each triangle indicates the number of viable C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria recovered from a cecum. n indicates the number of birds in the group of 10 from which no viable C. jejuni bacteria were recovered (limit of detection, 103 CFU/gram cecal contents). The bar indicates the mean number of bacteria that were recovered from only those birds that were colonized with C. jejuni.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to determine if C. jejuni strains compete for colonization in broiler chicks. To address this question, we first selected two C. jejuni isolates that effectively colonize chickens and isolated nalidixic acid- and streptomycin-resistant strains. Using the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains, we performed motility assays, growth curve analyses, real-time RT-PCR to measure the expression of transcripts for known and putative adhesins, and in vitro adherence assays to characterize the phenotypic properties and better understand the interplay between two C. jejuni isolates. Overall, several similarities and differences were noted between the two strains. Regarding the similarities, both C. jejuni strains expressed comparable transcript levels of the known and putative adhesins (data not shown) and bound to LMH chicken hepatocellular carcinoma epithelial cells. While the levels of the transcripts differed for the different genes (the expression levels, from highest to lowest, were those of porA, cadF, peb1, and jlpA), no significant differences were detected in the levels of transcript from a given gene between the two strains. However, this does not preclude the possibility that there are functional characteristics of the adhesins that differ between strains due to sequence variation in the encoding genes. Regarding the differences, the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain did appear more motile than the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain based on the zone of migration of the two isolates on MH agar plates supplemented with 0.4% agar. In addition, the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain had a higher growth rate than the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain, although both strains reached similar concentrations of CFU/ml in stationary phase (i.e., 54 h). Finally, the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain bound to the LMH chicken cells in greater numbers than the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain.

We are unaware of other studies in which a cell line of chicken origin has been used to assess the binding potential of C. jejuni isolates. Although the LMH chicken epithelial cells are derived from the liver (i.e., hepatocellular carcinoma), preliminary assays revealed that the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain exhibited the same binding potential with INT 407 and LMH epithelial cells (not shown). Moreover, similar numbers of C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria were bound to the INT 407 and LMH cells. Together, these findings suggest that these two eukaryotic cells, despite their different origins, both possess receptor sites to which the C. jejuni adhesins can attach. All subsequent adherence assays were performed using the LMH cells because these cells might better reflect the behavior of C. jejuni in the chicken digestive tract. Direct comparison of the binding potential of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains revealed that the F38011 Nalr bacteria bound to the LMH cells in greater numbers than were observed with the 02-833L Strr bacterial strain. Both bacterial strains bound to the peripheries of the LMH cells as judged by IF microscopy examination. Interestingly, the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain competitively inhibited the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain to LMH cells, but an excess of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr bacteria did not reduce the binding of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain to LMH cells. The reason why one strain is able to inhibit the binding of another strain, but not vice versa, is not known. Possible reasons include that (i) the C. jejuni 02-833L strain possesses an adhesin(s) not synthesized by the C. jejuni F38011 strain or (ii) the C. jejuni 02-833L strain appears more motile than the C. jejuni F38011 strain and therefore may be able to reach host cell receptor sites not accessible by the F38011 strain (i.e., receptors on the basolateral surfaces of cells) despite the centrifugation step used to promote contact with the LMH cells. Strains with greater motilities may have the advantage in vivo because C. jejuni bacteria preferentially colonize the mucus-filled cecal crypts. The inhibition of the binding of the C. jejuni F38011 strain with the 02-833L strain was judged to be specific because the effect was dose dependent and was not observed when S. enterica serovar Typhimurium was used as the competitor strain. Of even greater interest, the C. jejuni 02-833L strain significantly reduced the number of birds colonized with the C. jejuni F38011 strain in the competitor experiments. The in vivo experiments also revealed that the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain did have an effect, although minimal, on the colonization of the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain. The numbers of C. jejuni 02-833L Strr bacteria recovered from the cecal contents (group 5) varied over a greater range than those from either the birds inoculated with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain only (group 3) or the birds inoculated first with the C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain and then with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr strain (group 6). Noteworthy is that the in vitro assays were a good indicator of the results generated from the in vivo experiments.

Analysis of the data generated from the in vivo experiments uncovered several points worth mentioning. First, the numbers of bacteria recovered from the intestinal tracts showed greater variability than the numbers of bacteria recovered from the cecal contents, which consistently contained the greatest numbers of C. jejuni bacteria. We have consistently recovered higher numbers of C. jejuni bacteria from the cecum than from the mid-intestine in pilot studies using the same sampling techniques as those described above (data not shown). Second, it is clear that in some of the birds, colonization with one C. jejuni strain was able to completely inhibit a second strain from establishing colonization. While the mechanism underlying this competitive inhibition is not understood, this finding certainly warrants further investigation. Third, chickens can also harbor more than one strain of C. jejuni. Although we used a relatively high challenge dose (i.e., 107 bacteria) for these experiments, the sources of C. jejuni in the farm environment are not known and the dose range for C. jejuni probably varies over several logs. Fourth, there appears to be an upper limit to the number of bacteria colonizing the cecum. The mean numbers of bacteria recovered from the ceca of the birds inoculated with the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strains (groups 4, 5, and 6) were 4.9 × 1010, 4.5 × 1010, and 3.0 × 1010, respectively. If there is indeed an upper limit to the number of C. jejuni bacteria that can be present in the cecum, it would mean that one strain must be partially displaced for a second strain to establish colonization.

A lack of stability in the C. jejuni genome has been observed after passage of the bacteria through an animal or from human infections (6, 21, 34, 37). Following inoculation of newly hatched chicks with C. jejuni isolates, Hänninen et al. (6) observed genotypic variants in 2 of 12 isolates. Steinbrueckner et al. (34) observed variations in genotypes of C. jejuni isolates cultured from human stool samples from several patients over time. To assess whether the strains used in our study were subject to genomic instability, approximately 10 colonies were recovered from plates for each of groups 2 to 6 and the macrorestriction profiles (mrp) determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. This type of analysis was possible because the C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and C. jejuni 02-833L Strr (parental) strains, which were used to inoculate the chickens, had distinct macrorestriction profiles. All of the Nalr colonies recovered exhibited the SmaI mrp of the C. jejuni F38011 parental strain, and all of the Strr colonies recovered exhibited the SmaI mrp of the parental C. jejuni 02-833L Strr strain. Moreover, Nalr and Strr colonies were never recovered from the cecal samples. In addition, the motility of each of the isolates from cecal contents was determined to be equivalent to that of the parental strain (data not shown). Collectively, these data suggest that the populations of C. jejuni F38011 Nalr and 02-833L Strr strains in the chickens remained constant.

In summary, we performed in vitro and in vivo adherence and colonization assays with one C. jejuni clinical strain recovered from a human with bloody diarrhea and one C. jejuni environmental strain recovered from a chicken to gain a better understanding of bacterium-host cell interactions. Although the significance of the results is strain specific, both the in vitro and the in vivo experiments revealed that one C. jejuni strain could competitively inhibit the second strain from binding to epithelial cells and colonizing chicks. Most interesting was that in several instances, chickens colonized with the C. jejuni 02-833L strain were refractory to colonization with the C. jejuni F38011 strain. This finding provides a foundation for additional experiments to be performed to explore the interplay between C. jejuni strains within a host and to further dissect the complex nature of C. jejuni colonization of chickens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stuart Perry for animal care. We also thank Sylvia K. Weber and Fonda Wier for assistance in preparing samples for processing. Finally, we thank Phil Mixter and Sophia Pacheco (School of Molecular Biosciences, Washington State University) for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the USDA NRI (proposal no. 2006-35201-17305) and a grant from the USDA National Research Initiative through the Food Safety Research Response Network (2005-35212-15287) awarded to M.E.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaser, M. J., J. G. Wells, R. A. Feldman, R. A. Pollard, and J. R. Allen. 1983. Campylobacter enteritis in the United States. A multicenter study. Ann. Intern. Med. 98:360-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Melo, M. A., and J.-C. Pechère. 1990. Identification of Campylobacter jejuni surface proteins that bind to eucaryotic cells in vitro. Infect. Immun. 58:1749-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle, M. P., and M. P. Jones. 1992. Food-borne transmission and antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter jejuni, p. 45-48. In I. Nachamkin, M. J. Blaser, and L. S. Tompkins (ed.), Campylobacter jejuni. Current status and future trends. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 4.Fauchère, J.-L., M. Kervella, A. Rosenau, K. Mohanna, and M. Veron. 1989. Adhesion to HeLa cells of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli outer membrane components. Res. Microbiol. 140:379-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauchère, J. L., A. Rosenau, M. Veron, E. N. Moyen, S. Richard, and A. Pfister. 1986. Association with HeLa cells of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from human feces. Infect. Immun. 54:283-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hänninen, M.-L., M. Hakkinen, and H. Rautelin. 1999. Stability of related human and chicken Campylobacter jejuni genotypes after passage through chick intestine studied by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2272-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs-Reitsma, W. F., A. W. van de Giessen, N. M. Bolder, and R. W. Mulder. 1995. Epidemiology of Campylobacter spp. at two Dutch broiler farms. Epidemiol. Infect. 114:413-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin, S., A. Joe, J. Lynett, E. K. Hani, P. Sherman, and V. L. Chan. 2001. JlpA, a novel surface-exposed lipoprotein specific to Campylobacter jejuni, mediates adherence to host epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1225-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaldor, J., and B. R. Speed. 1984. Guillain-Barré syndrome and Campylobacter jejuni: a serological study. Br. Med. J. 288:1867-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelle, K., J. M. Pages, and J. M. Bolla. 1998. A putative adhesin gene cloned from Campylobacter jejuni. Res. Microbiol. 149:723-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kervella, M., J.-M. Pagès, Z. Pei, G. Grollier, M. J. Blaser, and J.-L. Fauchère. 1993. Isolation and characterization of two Campylobacter glycine-extracted proteins that bind to HeLa cell membranes. Infect. Immun. 61:3440-3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ketley, J. M. 1997. Pathogenesis of enteric infection by Campylobacter. Microbiology 143:5-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konkel, M. E., J. E. Christensen, A. M. Keech, M. R. Monteville, J. D. Klena, and S. G. Garvis. 2005. Identification of a fibronectin-binding domain within the Campylobacter jejuni CadF protein. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1022-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konkel, M. E., and W. Cieplak, Jr. 1992. Altered synthetic response of Campylobacter jejuni to cocultivation with human epithelial cells is associated with enhanced internalization. Infect. Immun. 60:4945-4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konkel, M. E., S. G. Garvis, S. L. Tipton, D. E. Anderson, Jr., and W. Cieplak, Jr. 1997. Identification and molecular cloning of a gene encoding a fibronectin-binding protein (CadF) from Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Microbiol. 24:953-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konkel, M. E., S. A. Gray, B. J. Kim, S. G. Garvis, and J. Yoon. 1999. Identification of the enteropathogens Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli based on the cadF virulence gene and its product. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:510-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konkel, M. E., M. R. Monteville, V. Rivera-Amill, and L. A. Joens. 2001. The pathogenesis of Campylobacter jejuni-mediated enteritis. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2:55-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuroki, S., T. Haruta, M. Yoshioka, Y. Kobayashi, M. Nukina, and H. Nakanishi. 1991. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with Campylobacter infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:149-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert, M. E., P. F. Schofield, A. G. Ironside, and B. K. Mandal. 1979. Campylobacter colitis. Br. Med. J. 1:857-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McSweegan, E., and R. I. Walker. 1986. Identification and characterization of two Campylobacter jejuni adhesins for cellular and mucous substrates. Infect. Immun. 53:141-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mixter, P. F., J. D. Klena, G. A. Flom, A. M. Siegesmund, and M. E. Konkel. 2003. In vivo tracking of Campylobacter jejuni by using a novel recombinant expressing green fluorescent protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2864-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monteville, M. R., and M. E. Konkel. 2002. Fibronectin-facilitated invasion of T84 eukaryotic cells by Campylobacter jejuni occurs preferentially at the basolateral cell surface. Infect. Immun. 70:6665-6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteville, M. R., J. E. Yoon, and M. E. Konkel. 2003. Maximal adherence and invasion of INT 407 cells by Campylobacter jejuni requires the CadF outer membrane protein and microfilament reorganization. Microbiology 149:153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moser, I., W. Schroeder, and J. Salnikow. 1997. Campylobacter jejuni major outer membrane protein and a 59-kDa protein are involved in binding to fibronectin and INT 407 cell membranes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:233-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moser, I., W. F. K. J. Schröder, and E. Hellmann. 1992. In vitro binding of Campylobacter jejuni/coli outer membrane preparations to INT 407 cell membranes. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 180:289-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pei, Z., and M. J. Blaser. 1993. PEB1, the major cell-binding factor of Campylobacter jejuni, is a homolog of the binding component in Gram-negative nutrient transport systems. J. Biol. Chem. 268:18717-18725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pei, Z., C. Burucoa, B. Grignon, S. Baqar, X.-Z. Huang, D. J. Kopecko, A. L. Bourgeois, J.-L. Fauchère, and M. J. Blaser. 1998. Mutation in the peb1A locus of Campylobacter jejuni reduces interactions with epithelial cells and intestinal colonization of mice. Infect. Immun. 66:938-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pei, Z., R. T. Ellison III, and M. J. Blaser. 1991. Identification, purification, and characterization of major antigenic proteins of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Biol. Chem. 266:16363-16369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaffl, M. W., G. W. Horgan, and L. Dempfle. 2002. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhodes, K. M., and A. E. Tattersfield. 1982. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with Campylobacter infection. Br. Med. J. 285:173-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson, D. A. 1981. Infective dose of Campylobacter jejuni in milk. Br. Med. J. 282:1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schröder, W., and I. Moser. 1997. Primary structure analysis and adhesion studies on the major outer membrane protein of Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 150:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skirrow, M. B., and M. J. Blaser. 1992. Clinical and epidemiologic considerations, p. 3-8. In I. Nachamkin, M. J. Blaser, and L. S. Tompkins (ed.), Campylobacter jejuni. Current status and future trends. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 34.Steinbrueckner, B., F. Ruberg, and M. Kist. 2001. Bacterial genetic fingerprint: a reliable factor in the study of the epidemiology of human Campylobacter enteritis? J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4155-4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stern, N. J. 1992. Reservoirs for Campylobacter jejuni and approaches for intervention in poultry, p. 49-60. In I. Nachamkin, M. J. Blaser, and L. S. Tompkins (ed.), Campylobacter jejuni. Current status and future trends. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 36.Syn, C. K., W. L. Teo, and S. Swarup. 1999. Three-detergent method for the extraction of RNA from several bacteria. BioTechniques 27:1140-1141, 1144-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wassenaar, T. M., B. Geilhausen, and D. G. Newell. 1998. Evidence of genomic instability in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1816-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuki, N., T. Taki, F. Inagaki, T. Kasama, M. Takahashi, K. Saito, S. Handa, and T. Miyatake. 1993. A bacterium lipopolysaccharide that elicits Guillain-Barré syndrome has a GM1 ganglioside-like structure. J. Exp. Med. 178:1771-1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziprin, R. L., C. R. Young, L. H. Stanker, M. E. Hume, and M. E. Konkel. 1999. The absence of cecal colonization of chicks by a mutant of Campylobacter jejuni not expressing bacterial fibronectin-binding protein. Avian Dis. 43:586-589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]