Abstract

The spx gene of Bacillus subtilis encodes a global regulator that controls transcription initiation in response to oxidative stress by interaction with RNA polymerase (RNAP). It is located in a dicistronic operon with the yjbC gene. The spx gene DNA complements an spx null mutation with respect to disulfide stress resistance, suggesting that spx is transcribed from a promoter located in the intergenic region of yjbC and spx. Transcription of the yjbC-spx operon has been reported to be driven by four promoters, three (P1, P2, and PB) residing upstream of yjbC and one (PM) located in the intergenic region between yjbC and spx. Primer extension analysis uncovered a second intergenic promoter, P3, from which transcription is elevated in cells treated with the thiol-specific oxidant diamide. P3 is utilized by the σA form of RNA polymerase in vitro without the involvement of a transcriptional activator. Transcriptional induction from P3 did not require an Spx-RNAP interaction and was observed in a deletion mutant lacking DNA upstream of position −40 of the P3 promoter start site. Deletion mutants with endpoints 3′ to the P3 transcriptional start site (positions +5, +15, and +30) showed near-constitutive transcription at the induced level, indicating the presence of a negative control element downstream of the P3 promoter sequence. Point mutations characterized by bgaB fusion expression and primer extension analyses uncovered evidence for a second cis-acting site in the P3 promoter sequence itself. The data indicate that spx transcription is under negative transcriptional control that is reversed when disulfide stress is encountered.

The spx gene of Bacillus subtilis was discovered to be the site of mutations that suppressed null alleles of clpX and clpP with respect to competence development, sporulation gene expression, and growth in minimal medium (14, 27). It was later characterized as an RNA polymerase (RNAP)-binding protein that repressed activator-stimulated transcription and activated transcription initiation at the trxA (thioredoxin) and trxB (thioredoxin reductase) promoters in response to oxidative stress (16-18, 20). Recent reports indicated that Spx is an important regulatory factor in the stress response in Staphylococcus aureus (21) and during Listeria monocytogenes infection (3). Spx concentration and activity increase when cells encounter a toxic oxidant that brings about disulfide stress (16, 17). Increases in Spx protein concentration are associated with a variety of stress conditions (24) including heat, salt, disulfide, and peroxide stress.

The spx gene resides in the yjbC-spx dicistronic operon located between the opp operon and the mecA gene (Fig. 1A). Previous studies uncovered the complexity of the yjbC-spx operon's transcriptional organization (1). Four kinds of RNAP holoenzymes recognize promoter DNA sequences at the 5′ end of the operon and in the intergenic DNA between yjbC and spx. Upstream of the yjbC coding sequence are three putative transcription start sites uncovered by primer extension studies: P1, recognized by the σA form of RNAP, and P2 and PB, utilized by the σW and σB RNAP holoenzymes, respectively. In the yjbC-spx intergenic region, the PM promoter was identified (25), which is utilized by the σM form of RNAP. The σB RNAP holoenzyme is a crucial component of the general energy and environmental stress responses (6). The σW holoenzyme form is required for the transcription of genes that are induced by envelope stress, antimicrobial agents, and superoxide stress (2, 8, 9). Hence, part of the reason why the Spx concentration increases in response to stress might be the activities of the RNAP holoenzyme forms that utilize promoters of the yjbC-spx operon.

FIG. 1.

(A) Organization of the yjbC-spx operon. Promoters (P1, P2, and PB) of yjbC are indicated by bent arrows, as is the PM promoter of the spx gene recognized by σM RNAP. The arrow beneath the operon diagram indicates 1.2-kb mRNA identified by Northern blot analysis (hybridization-labeled probe specific for yjbC) (1). The spx promoter P3 is indicated by the bold, bent arrow. (B) Sequence of the spx P3 promoter region. The −10 and −35 promoter sequences are indicated by boldface, underlined type. The P3 transcription start site is marked by +1 and an arrow. The nucleotide sequence of the labeled primer used in the primer extension experiments is underlined. The nucleotide sequence of the spx coding sequence is shown in lowercase type. (C) Denaturing polyacrylamide gel profile of a primer extension (PE) reaction using RNA extracted from JH642 cells. The sequencing reaction and primer extension utilized the primer described in B. (D) Denaturing polyacrylamide gel profile of in vitro runoff transcription products of reaction mixtures containing purified RNAP (100 nM), spx promoter DNA (0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μM as indicated), and radiolabeled nucleotide triphosphate mix. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 20 min.

In this report, the discovery of a fifth promoter in the yjbC-spx operon intergenic region is described. It is activated when B. subtilis cells are treated with the thiol-specific oxidant diamide (10). The P3 promoter is utilized by the σA form of RNAP and is associated with two negative control elements. The accompanying paper describes the two repressors that target the spx P3 promoter region (10a).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacillus subtilis strains used in this study are derivatives of JH642 and are listed in Table 1. Cells were cultivated in a shaking water bath at 37°C in Difco sporulation medium (DSM) for β-galactosidase assays or TSS minimal medium (4) for diamide treatment experiments (17). Diamide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used at a concentration of 1 mM to induce disulfide stress.

TABLE 1.

Bacillus subtilis strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant phenotype or descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | J. A. Hoch |

| ORB3621 | trpC2 pheA1 rpoA(Y263C) | 15 |

| ORB3834 | trpC2 pheA1 spx::neo | 14 |

| ORB4888 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PyjbC-spx-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB4889 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB4980 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx?−40-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB4981 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ−60-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB4982 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ−100-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB5058 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ+50(wt)-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB5077 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ+5-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB5078 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ+15-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB5079 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ+30-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB5107 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ+50(wild type)-bgaB cat spx::neo | This study |

| ORB5115 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::PspxΔ+40-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB6030 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx(T−26A)-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB6031 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx(T−20G)-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB6032 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx(T−19G)-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB6033 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx(A−14T)-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB6034 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx(A+3G)-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB6035 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx(T+7C)-bgaB cat | This study |

| ORB6036 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::Pspx(T+24C)-bgaB cat | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSN16 | yjbC-spx-lacZ fusion plasmid | 19 |

| pML11 | yjbC-spx transcriptional fusion in pUC19 | This study |

| pML18 | yjbC-spx transcriptional fusion in pDL | This study |

| pML19 | spx transcriptional fusion in pDL | This study |

| pML20 | spx promoter fragment (−40) in pDL | This study |

| pML21 | spx promoter fragment (−60) in pDL | This study |

| pML22 | spx promoter fragment (−100) in pDL | This study |

| pML23 | yjbC promoter fragment in pDL | This study |

| pML25 | spx promoter fragment (wild type +50) in pUC19 | This study |

| pML26 | spx promoter fragment (wild type +50) in pDL | This study |

| pML27 | spx promoter fragment (+5) in pUC19 | This study |

| pML28 | spx promoter fragment (+15) in pUC19 | This study |

| pML29 | spx promoter fragment (+30) in pUC19 | This study |

| pML30 | spx promoter fragment (+5) in pDL | This study |

| pML31 | spx promoter fragment (+15) in pDL | This study |

| pML32 | spx promoter fragment (+30) in pDL | This study |

| pML33 | spx promoter fragment (+40) in pUC19 | This study |

| pML34 | spx promoter fragment (+40) in pDL | This study |

| pML35 | Random mutagenesis of spx promoter in pUC19 | This study |

| pML36 | Random mutagenesis of spx promoter in pDL | This study |

| pML42 | spx(T−26A) in pDL | This study |

| pML43 | spx(T−20G) in pDL | This study |

| pML44 | spx(T−19G) in pDL | This study |

| pML45 | spx(A3G) in pDL | This study |

| pML46 | spx(A−14T) in pDL | This study |

| pML47 | spx(T7C) in pDL | This study |

| pML48 | spx(T24C) in pDL | This study |

wt, wild type.

Construction of yjbC and spx transcriptional fusions.

The yjbC-spx promoter region was amplified by PCR using primers oML02-17 and oML02-6 (Table 2). The product was digested with BamHI and BclI and then inserted into pUC19 digested with BamHI to generate pML11. The cloned yjbC-spx DNA was verified by DNA sequencing and was then digested with BamHI and SmaI to release the fragment containing 420 bp upstream of the yjbC start codon to 187 bp downstream of the start codon. The resulting fragment was then subcloned into plasmid pDL to construct pML18, a plasmid bearing a bgaB fusion, encoding thermostable β-galactosidase (26), and the yjbC-spx intergenic region. The fragment released from pML18 by EcoRI digestion and containing 538 bp upstream of the P3 start site to 187 bp downstream of the spx start codon was inserted into plasmid pDL to generate pML19, the spx-bgaB fusion.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| oMLbgaB | 5′-CCCCCTAGCTAATTTTCGTTTAATTA-3′ |

| oML02-6 | 5′-GATGATACGATCTATTAGTTTGCCAAAC-3′ |

| oML02-7 | 5′-CCCAAGCTTGCATTTCAAGCATGCTCAG-3′ |

| oML02-10 | 5′-TCAATTGGAAAGTACTCGCTAAGC-3′ |

| oML02-15 | 5′-TCCTCTAATTAGTAGGATGAACAT-3′ |

| oML02-22 | 5′-CGGGATCCCGAACATCTATTTTATTC-3′ |

| oML02-23 | 5′-GGAATTCCGATACTGTTCACACTT-3′ |

| oML02-24 | 5′-GGAATTCCTTGACACATTTTTTTC-3′ |

| oML02-25 | 5′-GGAATTCCAGAATAAGAACATATC-3′ |

| oML02-26 | 5′-CGGGATCCTCTTTACAGGTATTA-3′ |

| oML02-27 | 5′-CGCGGATCCAAAAAAGGAATCTTT-3′ |

| oML02-28 | 5′-CGCGGATCCAATTGAAATTACTC-3′ |

| oML02-29 | 5′-CGCGGATCCTTTATTCTTAAATTG-3′ |

| oML02-37 | 5′-GGAATTCCGGTACCGGCGCCGGTCATT-3′ |

| oML02-38 | 5′-GTTCACACaTACTTTTTTATAG-3′ |

| oML02-39 | 5′-AAAAGTAtGTGTGAACAGTATCC-3′ |

| oML02-40 | 5′-CACTTACTTgTTTATAGTATAATACC-3′ |

| oML02-41 | 5′-CTATAAAcAAGTAAGTGTGAAC-3′ |

| oML02-42 | 5′-CACTTACTTTgTTATAGTATAATACC-3′ |

| oML02-43 | 5′-CTATAAcAAAGTAAGTGTGAAC-3′ |

| oML02-44 | 5′-ACTTTTTTATtGTATAATACCTG-3′ |

| oML02-45 | 5′-CTATAAcAAAGTAAGTGTGAAC-3′ |

| oML02-46 | 5′-ACCTGTAAgGATTCCTTTTTTAGAG-3′ |

| oML02-47 | 5′-AGGAATCcTTACAGGTATTATACT-3′ |

| oML02-48 | 5′-GTAAAGATcCCTTTTTTAGAGTAA-3′ |

| oML02-49 | 5′-CTAAAAAAGGgATCTTTACAGGT-3′ |

| oML02-50 | 5′-GAGTAATcTCAATTTAAGAATAA-3′ |

| oML02-51 | 5′-TAAATTGAgATTACTCTAAAAAAGG-3′ |

Bases in lowercase type are mutagenic.

Constructions of promoter deletion mutations.

The spx 3′ promoter region was amplified by PCR using primer oML02-7 in combination with oML02-22 (+50 region) (wild type), oML02-26 (+5 region), oML02-27 (+15 region), oML02-28 (+30 region), or oML02-29 (+40 region) (Table 2). The products were digested with BamHI and KpnI and then inserted into pUC19 digested with the same enzymes to generate pML25, pML27, pML28, pML29, and pML33, respectively. The spx sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. The plasmids were digested with BamHI and EcoRI to release a fragment extending from 330 bp upstream from the P3 start site to the 3′ deletion endpoint. The fragments were then inserted into plasmid pDL that was digested with the same enzymes to generate pML26, pML30, pML31, pML32, and pML34, respectively. The spx 5′ promoter deletion region was amplified by PCR using primer oML02-22 in combination with oML02-23 (−40 region), oML02-24 (−60 region), or oML02-25 (−100 region) (Table 2). The products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and then inserted into pDL that was digested with the same enzymes to generate pML20, pML21, and pML22, respectively. The fragments extended from the 5′ deletion endpoint to 50 bp downstream of the P3 transcription start site. The spx sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. The strains bearing wild-type spx and 5′ and 3′ spx deletion promoter-bgaB fusions were ORB5058 (wild type), ORB4980 (−40 region), ORB4981 (−60 region), ORB4982 (−100 region), ORB5077 (+5 region), ORB5078 (+15 region), ORB5079 (+30 region), and ORB5115 (+40 region). Cells bearing the promoter-bgaB fusions were grown in DSM until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached ∼0.4 to 0.5. After further incubation for 30, 60, and 120 min, samples of cells were harvested and prepared for β-galactosidase assays.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

T−26A, T−20G, T−19G, A−14T, A+3G, T+7C, and T+24C mutant alleles of spx were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. First-round PCR was performed in two separate reactions with primer oMLbgaB in combination with oML02-38, oML02-40, oML02-42, oML02-44, oML02-46, oML02-48, or oML02-50 (Table 2) using pML26 as a template and primer oML02-37 in combination with oML02-39, oML02-41, oML02-43, oML02-45, oML02-47, oML02-49, or oML02-51 (Table 2) using pSN16 (19) as a template. The PCR products were hybridized and subsequently amplified by a second round of PCR using oML02-37 and oML02-22. The products from a second round of PCR were then digested with EcoRI and BamHI restriction enzymes (to release the PCR fragment from positions −330 to +50 relative to the P3 transcription start site) and inserted into pDL digested with the same enzymes to generate pML42, pML43, pML44, pML46, pML45, pML47, and pML48, respectively. The spx sequences in the plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. The spx promoter point mutant strains used for β-galactosidase assays and primer extension analyses were ORB6030 (T−26A), ORB6031 (T−20G), ORB6032 (T−19G), ORB6033 (A−14T), ORB6034 (A+3G), ORB6035 (T+7C), and ORB6036 (T+24C).

Assays of β-galactosidase activity.

Assays of BgaB activity were performed according to previously published methods (23). Activity was expressed as Miller units (12). The data from β-galactosidase assays are presented with standard deviations for three to four independent experiments.

Primer extension analysis.

Cultures of wild-type and P3 promoter mutant strains were grown at 37°C in TSS medium. At mid-log phase, the culture was split into two cultures, and diamide was added to one culture to a final concentration of 1 mM. Aliquots (20 ml) of cultures were withdrawn for RNA preparation at time zero (mid-log phase) and after 10 min with or without diamide (1 mM) treatment. The culture was mixed with an equal volume of ice-cold methanol; after centrifugation, the cell pellet was frozen at −80°C. The total RNA was prepared by using an RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Chatworth, CA). The primer corresponding to the bgaB sequence downstream of the inserted fragment (oMLbgaB) as well as primer oML02-15 (specifying the endogenous spx sequence) were used to examine the transcript of spx fusions and endogenous spx. Primer oML02-10 was used to examine the transcript of yjbC. The same amount of RNA used in the primer extension was applied to a formaldehyde-agarose gel. 16S rRNA was visualized by staining with ethidium bromide to confirm that comparable amounts of total RNA were used for each reaction mixture.

In vitro transcription assay.

A linear DNA template for the spx promoter was generated by PCR with primers oML02-7 and oML02-15 using plasmid pML18 as the template (encoding a ∼70-base transcript). The 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μM DNA templates were mixed with 100 nM RNAP in a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 5 mM dithiothreitol at 37°C for 10 min. A nucleotide mixture (200 μM ATP, GTP, and CTP, 10 μM UTP, 10 μCi [α-32P]UTP) was added to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixtures (20 μl) were further incubated at 37°C for 20 min, and the transcripts were precipitated by ethanol. Electrophoresis was performed as described previously (11).

UV irradiation mutagenesis.

ORB5107 (Pspx-bgaB spx::neo) was grown in liquid DSM until the OD600 reached 0.7 to 1.0. Cells were harvested and washed with 0.1 M MgSO4. Cells were resuspended in 0.1 M MgSO4 and then irradiated (UV Stratalinker 1800) for 4 min. Irradiated cells were kept on ice and in the dark. Serial dilutions of untreated cells and UV-treated cells were plated onto DSM plates for counting isolated colonies to determine the survival rate. The frequency of auxotrophic mutants among the UV-treated cells was determined by replica plating onto TSS agar containing 0.1% tryptophan and phenylalanine.

Error-prone PCR mutagenesis.

The spx promoter region was amplified by PCR using primers oML02-7 and oML02-22. The error-prone PCR mixture contained error-prone PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2), 0.3 mM MnCl2, 0.2 μM of each primers, 0.2 mM of dATP and dGTP, and 1 mM of dCTP and dTTP. The product was digested with KpnI and BamHI and then inserted into pUC19. The pooled plasmid was digested with EcoRI and BamHI, followed by subcloning into plasmid pDL. The recombinant pDL pool was used to transform JH642 to generate the strain bearing random nucleotide substitutions within the spx promoter region. The transformants were screened for blue colonies on the DSM plates containing X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). The BgaB phenotype of the blue colony isolates was confirmed by β-galactosidase assays of samples collected from liquid DSM cultures. Confirmed BgaB+ variants were analyzed by sequence analysis of the mutagenized spx promoter region.

RESULTS

Identification of the P3 promoter within the yjbC-spx operon.

Fig. 1 shows the genomic location and the organization of the yjbC-spx operon of B. subtilis. The yjbC operon resides between the opp (spo0K) operon and the mecA gene (Fig. 1A). Upstream of yjbC are three promoters, two of which are recognized by the σW (P2) and σB (PB) forms of RNAP (1, 2, 22). The yjbC coding sequence is followed by an intergenic region of 184 bp that contains the previously described PM promoter of spx that is recognized by the σM form of RNAP. The spx gene coding sequence begins 123 bp downstream of the start point of the PM promoter (Fig. 1B) (25). Because Spx activity and concentration are elevated upon oxidative stress, we felt that the transcription of the spx gene might be controlled in response to the presence of a toxic oxidant (diamide). Primer extension analysis of total JH642 RNA using primers specific for spx and yjbC was conducted to determine if transcription from the various promoters of the yjbC-spx operon was induced by diamide treatment. No elevation of yjbC transcript levels was observed upon disulfide stress (data not shown, but see Fig. 5D), but a transcript from a previously unidentified transcription start site was detected (Fig. 1C), and its concentration increased upon diamide treatment (see below). The start site of transcription from the new P3 promoter resides 79 bp from the start of the spx coding sequence. The same start site was utilized by purified RNAP in vitro, as shown in the gel profile of the runoff transcription products in Fig. 1D. No transcription from the PM promoter in vivo or in vitro was detected.

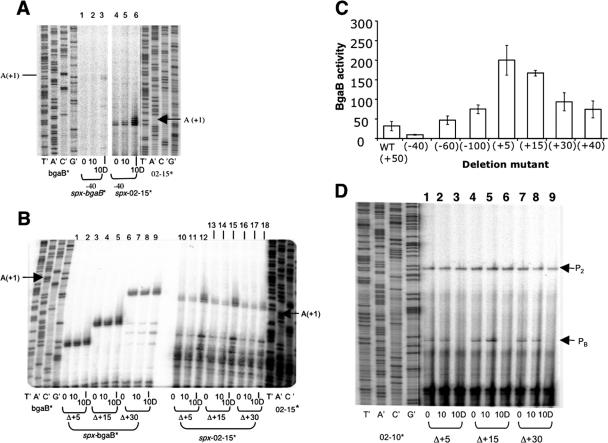

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis of RNA extracted from −40 deletion ORB4980 cells (A) and 3′ deletion ORB5077 (Δ+5), ORB5078 (Δ+15), and ORB5079 (Δ+30) cells (B and C) in TSS cultures subjected to diamide treatment. Cells were treated with 1 mM diamide for 10 min (10D) and without diamide (0 and 10 min) after the OD600 reached 0.4 to 0.5. Labeled primers specific to the bgaB fusion (bgaB*) and endogenous spx (02-15*) were used to detect spx transcripts. Marker lanes of sequencing reactions show the nucleotide positions corresponding to the spx-bgaB (A and B) and endogenous spx (A and B) start points. (A) Primer extension analysis of spx-bgaB and endogenous spx transcripts in total RNA extracted from the −40 deletion strain (ORB4980). (B) Primer extension analysis of spx-bgaB and endogenous spx transcripts in total RNA extracted from 3′ deletion strains ORB5077 (Δ+5), ORB5078 (Δ+15), and ORB5079 (Δ+30). (C) Expression of spx-bgaB fusion derivatives bearing promoter deletions as determined by assays of spx-directed β-galactosidase activity. Cells were grown in DSM. The expression was determined as BgaB activity in Miller units 30 min after cultures reached the mid-log phase. WT, wild type. (D) Primer extension analysis of yjbC transcripts in total RNA extracted from 3′ deletion strains.

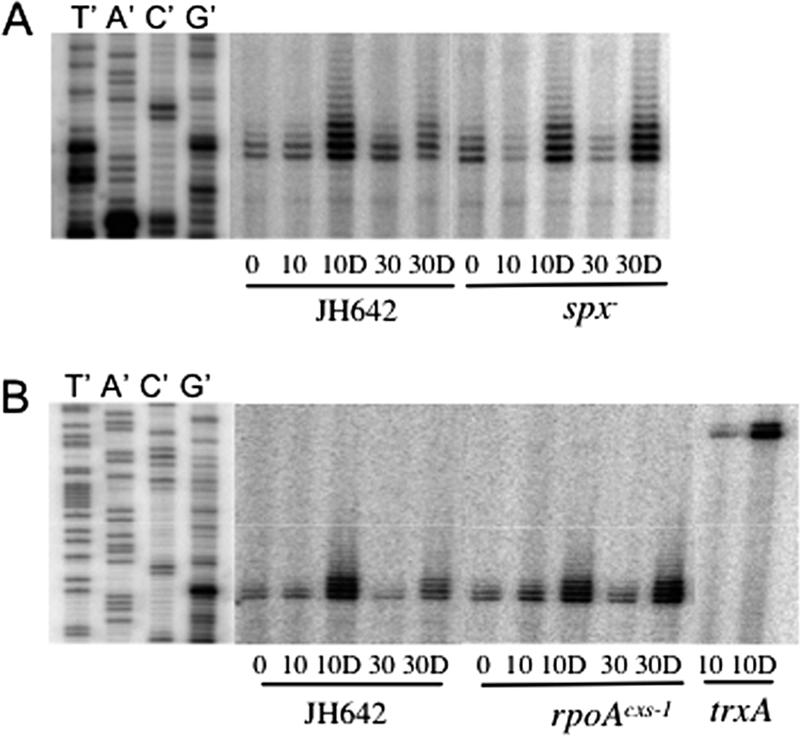

Diamide-dependent induction of transcription from P3 does not require Spx.

Transcription of spx from P3 in cells of cultures that were subjected to disulfide stress was examined. RNA was isolated from wild-type or spx mutant cultures before and after 10 and 30 min of diamide treatment. Denaturing gel analysis of primer extension reactions showed that transcript levels increased after 10 min of diamide treatment of wild-type and spx mutant cells (Fig. 2A). The Spx-dependent induction of trxA (encoding thioredoxin) transcription by diamide (17) was included as a control (Fig. 2B). A similar pattern of transcriptional induction was observed in cells bearing the rpoAcxs-1 mutation (Fig. 2B), which renders the RNAP α C-terminal domain unable to interact with Spx. Thus, it was shown that the induction of spx transcription from the P3 promoter by diamide treatment did not require the interaction of Spx with RNAP, which is required for trxA and trxB transcription.

FIG. 2.

Primer extension analysis shows the increase in spx transcript levels after diamide treatment. Total RNA was extracted from cells grown in TSS medium and harvested at mid-log phase (0) and then after cells were treated for 10 and 30 min with 1 mM diamide (10D and 30D, respectively) and without diamide (10 and 30, respectively). The labeled primer shown in Fig. 1B was used for primer extension reactions. The gel profile of the primer extension reaction using a trxA-specific primer (17) was a control for diamide-induced transcript accumulation. The dideoxy sequencing ladders are shown on the left. For dideoxynucleotide sequencing, the nucleotide complementary to the dideoxynucleotide added in each reaction mixture is indicated above the corresponding lane (T′, A′, C′, and G′). (A) Total RNA was extracted from wild-type JH642 and ORB3834 (spx null) cells. (B) Total RNA extracted from wild-type JH642 and ORB3621 (rpoAcxs-1) cells.

Examination of the primer extension signal at 30 min following diamide treatment shows that there is more spx transcript in the spx and rpoAcxs-1 cells than in those of the wild-type strain. This suggests that while the Spx-RNAP interaction might not be required for spx transcription, this interaction is necessary for the negative control required to restore expression to the prestress state.

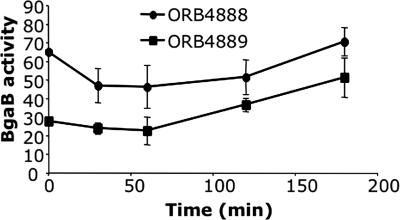

Transcription from the yjbC-spx intergenic region contributes substantially to the total expression of spx.

The yjbC-spx operon encodes a 1.2-kb RNA, which specifies the YjbC and Spx proteins (1). Previously described results (14, 25) and data presented in Fig. 1 and 2 show that the intergenic DNA contains at least two promoters that could drive spx expression. Two β-galactosidase (bgaB) fusions were constructed, and their expression was examined to determine to what extent the yjbC-spx intergenic region contributes to the expression of spx under nonstress conditions. The yjbC-spx-bgaB fusion of strain ORB4888 contained a fragment extending from the stop codon of spx at its 3′ end to 420 bp upstream of the yjbC coding sequence. The spx-bgaB fusion of strain ORB4889 contains a fragment bearing the same 3′ end as in the yjbC-spx-bgaB fusion, but its 5′ end is 538 bp upstream of the P3 start site, a point within the yjbC coding sequence. As shown in the time course experiment depicted in Fig. 3, the promoters of the spx-bgaB fusion account for between 45 and 70% of the total bgaB activity directed by the yjbC-spx operon. Because the cells were grown in DSM at 37°C, the stress conditions that would lead to the maximal induction of σW and σB activity were likely not encountered. Such conditions might result in a much larger contribution to spx expression by the yjbC promoter region. Nevertheless, the results shown in Fig. 3 indicate that the spx gene contains transcriptional signals that direct expression independently of the yjbC transcription initiation region. This is in keeping with the observation that a fragment bearing the spx gene and the upstream intergenic region is sufficient for the complementation of an spx null mutation (17).

FIG. 3.

Assay of yjbC-spx- and spx-directed β-galactosidase (BgaB) activity. Expression of yjbC-spx-bgaB and spx-bgaB was determined as BgaB activity in Miller units. Cells were grown in DSM. Time zero indicates the mid-log phase. •, ORB4888 (yjbC-spx-bgaB); ▪, ORB4889 (spx-bgaB).

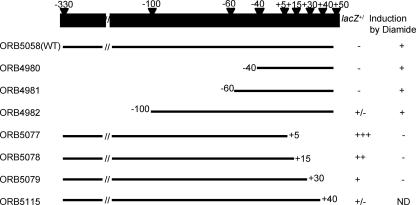

Deletion analysis uncovers cis-acting negative control elements associated with the P3 promoter.

The results depicted in Fig. 1D show that the P3 promoter can be utilized by purified σA RNAP in vitro without the presence of a positive control factor, suggesting that the diamide induction of P3 transcription might be caused by a reversal of negative control. To identify cis-acting control sequences associated with the P3 promoter, deletion and point mutational analyses were undertaken. Figure 4 summarizes the results of the deletion analysis of the spx promoter region. PCR-generated fragments in which sequences 5′ and 3′ of the P3 promoter were omitted were introduced into the bgaB fusion vector. The levels of BgaB activity and the level of transcript determined by primer extension reactions were assessed. BgaB activity was used as a measure of uninduced expression, since diamide induction cannot be observed using the enzyme assay due to the inactivation of BgaB. Therefore, induction was observed by measuring the increase in the level of transcript from both the spx-bgaB fusion and the endogenous spx gene using primer extension. The 5′ deletions had modest effects on the basal expression of spx, but diamide induction was still observed. However, deletions of the sequences 3′ of the P3 transcriptional start site resulted in higher basal-level expression.

FIG. 4.

Summary of deletion analysis of the spx P3 promoter region. The top bar shows the intact spx promoter and the positions of deletion endpoints relative to the transcription start site. All constructs generated by PCR were fused with the promoterless bgaB gene as the reporter. The bgaB expression levels from the respective fusions after integration into the chromosome were examined by screening on DSM agar plates containing 40 μg/ml X-gal (blue [+], white [−], and pale blue [+/−]). Transcriptional induction was determined by the extraction of RNA from diamide-treated and untreated cells bearing spx-bgaB fusions followed by primer extension analysis. + indicates that transcriptional induction after diamide treatment was detected. − indicates that a loss of induction was detected after diamide treatment. ND, no data.

A negative control element resides downstream of the P3 promoter sequence.

As summarized in Fig. 4, deletions of the 5′ end had little effect on the diamide-dependent induction of P3. This is shown in Fig. 5A, which is a gel profile of the primer extension reaction of RNA extracted from diamide-treated cells. A −40 deletion, which removes most of the DNA upstream of the P3 promoter, does not change the induction pattern of P3 transcription (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 to 3), which is also observed when the endogenous spx P3 transcript is examined (lanes 4 to 6). Deletion of the DNA 3′ of the P3 start site, with endpoints at positions +30, +15, and +5, results in an increase in basal-level transcription and a loss of diamide induction, as shown in primer extension experiments and in assays of spx-bgaB activity (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 9, and C). The same RNA used in the primer extension analysis of spx-bgaB promoter mutants was used to examine the level of endogenous spx transcript, which increased within 10 min of diamide treatment (Fig. 5B, lanes 10 to 18). The data shown in Fig. 5B are strong evidence for a negative control element in the region 3′ to the P3 promoter sequence.

Primer extension analysis also showed that the yjbC promoters do not contribute to the diamide induction of spx expression (Fig. 5D). The P2 and PB promoter transcripts can be detected in RNA from untreated cells, while diamide treatment has no effect on the level of P2 transcript but results in a loss of the PB transcript. At present, we do not know if this repression of PB is operon specific or due to a reduction of σB activity upon disulfide stress.

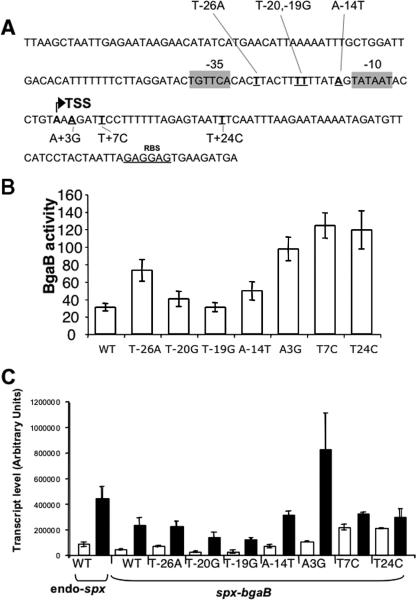

Point mutations suggest the presence of a second negative control site within the P3 promoter.

Experiments were conducted to uncover mutations in trans-acting loci, with hopes of identifying the putative repressor controlling transcription from P3. Cultures of spx-bgaB fusion-bearing cells were mutagenized by UV irradiation and examined for elevated BgaB activity on agar medium containing X-gal. Of the four variants isolated, all bore mutations in the intergenic region of yjbC-spx. In parallel experiments, in vitro mutagenesis by error-prone PCR was undertaken using a fragment of the P3 promoter region as a template. The pool of mutagenized fragments was inserted into the pDL bgaB fusion vector. All of the mutants obtained by the two procedures bore multiple nucleotide substitutions. Therefore, site-directed oligonucleotide mutagenesis was carried out to create single substitutions, the locations of which were chosen from the mutant sequences obtained from the UV mutagenesis and error-prone PCR experiments. Seven single-site mutants obtained (Fig. 6A) were analyzed by measuring spx-directed BgaB activity (Fig. 6B) and by primer extension analysis (Fig. 6C). Of the seven mutants, five showed elevated basal spx-bgaB expression (T−26A, A−14T, A3G, T7C, and T24C) (Fig. 6B) and higher levels of transcripts as shown in primer extension reactions with RNA from untreated cells (T−26A, A−14T, A3G, T7C, and T24C) (Fig. 6C). While the A3G substitution results in a generally higher level of transcript in both treated and untreated cells, the other mutations showing higher basal expression and transcript levels showed no increase in diamide-induced expression and, hence, have reduced induction ratios compared wild-type cells, indicating that these mutations reduce transcriptional repression under nonstress conditions. Our results provide evidence for a second cis-acting negative control region within the P3 promoter region.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of spx promoter P3 point mutations. (A) spx promoter region. The spx sequence along with the locations of seven nucleotide substitutions, as indicated by underlining (T−26A, T−20G, T−19G, A−14T, A+3G, T+7C, and T+24C), are shown. The bent arrow indicates the transcription start site (TSS). RBS, ribosome binding site. −10 and −35 promoter sequences are indicated by shaded boxes. (B) The PCR fragments of each point mutation bearing the spx sequence from position −330 to +50 were inserted into plasmid pDL (the bgaB fusion vector). The constructed plasmids were integrated into the amyE locus of B. subtilis. Cells were grown in DSM. The expression was determined as BgaB activity in Miller units 30 min after cultures reached the mid-log phase. (C) Primer extension analysis of point mutations in the P3 sequence of the spx-bgaB fusion after diamide treatment. The transcripts of the spx fusions and endogenous spx (endo-spx) of each point mutant without (white bars) and with (black bars) diamide treatment for 10 min are shown. RNA was extracted from cells harvested from cultures that reached an OD600 of 0.4 to 0.5. spx-bgaB transcripts were detected by primer extension analysis. Results, with standard deviations, for radiolabeled primer extension products from two independent RNA extracts and duplicate primer extension reactions for each extract are presented. endo-spx denotes the endogenous spx gene transcript level. WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

The transcription of spx is driven by five promoters of the yjbC-spx operon, although not all of the promoters are active under the culture growth conditions used in the study described herein. The promoters PM and P3 reside in the intergenic region of yjbC-spx, but only transcription from P3 is observed in the primer extension analysis of RNA from cells grown in minimal TSS medium, before and after diamide treatment. The P3 promoter contains a consensus −10 sequence that is utilized by the major σA form of RNA polymerase but has a −35 sequence that shows a 3-of-6-nucleotide match for the consensus −35 region. Levels of transcript synthesized from P3 increase 10 min after diamide treatment. Transcription from P3 is catalyzed by the σA holoenzyme in vitro without the requirement for an additional transcription factor, which suggested that transcription from P3 is under negative control. The intergenic region contributes significantly to spx transcription, as shown in experiments using yjbC-spx and spx-bgaB fusions and by complementation of an spx null mutation with respect to diamide sensitivity using a single copy of the spx gene with the accompanying yjbC-spx intergenic region. The Spx concentration increases after diamide treatment, which was shown to be due in part to posttranscriptional control of spx expression (17), perhaps by the downregulation of ClpXP-dependent proteolysis of Spx. However, the observation that spx transcription can be induced by disulfide stress suggests that transcriptional control can also contribute to elevated Spx levels during oxidative stress.

Mutational analysis of the regulatory region of the spx gene uncovered two negatively cis-acting elements. Deletions of sequences located downstream of the transcriptional start site of P3 resulted in higher basal-level transcription and a reduced diamide induction ratio. Based on these data, we propose that the mutations define an operator with which a negative transcriptional regulator interacts. Attempts at identifying a regulator involved a mutant search for trans-acting loci that might confer constitutive transcription from P3 and encode a repressor. No extragenic mutations conferring such a phenotype were isolated, but several cis-acting mutations were uncovered by screening mutants after UV mutagenesis. Five mutations, two downstream of the P3 transcriptional start site and three upstream and within the P3 promoter sequence, were observed to cause elevated basal transcription. Of these, four mutations, T−26A, A−14T, T7C, and T24C, reduced the diamide induction ratio and increased basal-level transcription. The T7C and T24C mutations likely affect the downstream operator defined by deletion analysis. We propose that the T−26 and A−14 positions define a second operator that is the interaction site of a second negative regulator. Our inability to uncover trans-acting loci that affect the control of P3 utilization suggested that there might be two mechanisms of negative control, and both must be reversed to ensure the proper induction of spx during disulfide stress; such a double mutant would likely be very rare.

Several transcriptome studies to identify the genes that are induced by oxidative stress or that are controlled by the peroxide response regulator PerR have been carried out (5, 7, 13). The study described previously by Hayashi et al. identified spx as being a member of the PerR regulon (5). The putative operator in the +5-to-+30 region contains at least one sequence bearing a resemblance to a PerR box. Indeed, as we show in the accompanying paper, the PerR protein binds to this region and, in doing so, represses spx transcription from P3 in vitro (10a). Furthermore, a second repressor encoded by the yodB gene was observed to bind to the second putative operator defined by the T−26A and A−14T mutations within the P3 promoter sequence. The description of this dual negative control of spx transcription appears in the accompanying paper (10a).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. M. Nakano for valuable discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Research reported herein was supported by grant GM45898 from the National Institutes of Health and by a grant from the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antelmann, H., C. Scharf, and M. Hecker. 2000. Phosphate starvation-inducible proteins of Bacillus subtilis: proteomics and transcriptional analysis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4478-4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao, M., P. A. Kobel, M. M. Morshedi, M. F. Wu, C. Paddon, and J. D. Helmann. 2002. Defining the Bacillus subtilis sigma(W) regulon: a comparative analysis of promoter consensus search, run-off transcription/macroarray analysis (ROMA), and transcriptional profiling approaches. J. Mol. Biol. 316:443-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee, S. S., H. Hossain, S. Otten, C. Kuenne, K. Kuchmina, S. Machata, E. Domann, T. Chakraborty, and T. Hain. 2006. Intracellular gene expression profile of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 74:1323-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouet, A., and A. L. Sonenshein. 1990. A target for carbon source-dependent negative regulation of the citB promoter of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 172:835-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi, K., T. Ohsawa, K. Kobayashi, N. Ogasawara, and M. Ogura. 2005. The H2O2 stress-responsive regulator PerR positively regulates srfA expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 187:6659-6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecker, M., and U. Volker. 1998. Non-specific, general and multiple stress resistance of growth-restricted Bacillus subtilis cells by the expression of the sigmaB regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helmann, J. D., M. F. Wu, A. Gaballa, P. A. Kobel, M. M. Morshedi, P. Fawcett, and C. Paddon. 2003. The global transcriptional response of Bacillus subtilis to peroxide stress is coordinated by three transcription factors. J. Bacteriol. 185:243-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoper, D., J. Bernhardt, and M. Hecker. 2006. Salt stress adaptation of Bacillus subtilis: a physiological proteomics approach. Proteomics 6:1550-1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, X., K. L. Fredrick, and J. D. Helmann. 1998. Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilis σW: autoregulation and partial overlap with the σX regulon. J. Bacteriol. 180:3765-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosower, N. S., and E. M. Kosower. 1995. Diamide: an oxidant probe for thiols. Methods Enzymol. 251:123-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Leelakriangsak, M., K. Kobayashi, and P. Zuber. 2007. Dual negative control of spx transcription initiation from the P3 promoter by repressors PerR and YodB in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 189:1736-1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, J., and P. Zuber. 2000. The ClpX protein of Bacillus subtilis indirectly influences RNA polymerase holoenzyme composition and directly stimulates sigmaH-dependent transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 37:885-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 13.Mostertz, J., C. Scharf, M. Hecker, and G. Homuth. 2004. Transcriptome and proteome analysis of Bacillus subtilis gene expression in response to superoxide and peroxide stress. Microbiology 150:497-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano, M. M., F. Hajarizadeh, Y. Zhu, and P. Zuber. 2001. Loss-of-function mutations in yjbD result in ClpX- and ClpP-independent competence development of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:383-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakano, M. M., Y. Zhu, J. Liu, D. Y. Reyes, H. Yoshikawa, and P. Zuber. 2000. Mutations conferring amino acid residue substitutions in the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase α can suppress clpX and clpP with respect to developmentally regulated transcription in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 37:869-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano, S., K. N. Erwin, M. Ralle, and P. Zuber. 2005. Redox-sensitive transcriptional control by a thiol/disulphide switch in the global regulator, Spx. Mol. Microbiol. 55:498-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakano, S., E. Küster-Schöck, A. D. Grossman, and P. Zuber. 2003. Spx-dependent global transcriptional control is induced by thiol-specific oxidative stress in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13603-13608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakano, S., M. M. Nakano, Y. Zhang, M. Leelakriangsak, and P. Zuber. 2003. A regulatory protein that interferes with activator-stimulated transcription in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4233-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano, S., G. Zheng, M. M. Nakano, and P. Zuber. 2002. Multiple pathways of Spx (YjbD) proteolysis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:3664-3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newberry, K. J., S. Nakano, P. Zuber, and R. G. Brennan. 2005. Crystal structure of the Bacillus subtilis anti-alpha, global transcriptional regulator, Spx, in complex with the alpha C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:15839-15844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pamp, S. J., D. Frees, S. Engelmann, M. Hecker, and H. Ingmer. 2006. Spx is a global effector impacting stress tolerance and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 188:4861-4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersohn, A., J. Bernhardt, U. Gerth, D. Hoper, T. Koburger, U. Volker, and M. Hecker. 1999. Identification of σB-dependent genes in Bacillus subtilis using a promoter consensus-directed search and oligonucleotide hybridization. J. Bacteriol. 181:5718-5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrogel, O., and R. Allmansberger. 1997. Optimisation of the BgaB reporter system: determination of transcriptional regulation of stress responsive genes in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 153:237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tam, L. T., H. Antelmann, C. Eymann, D. Albrecht, J. Bernhardt, and M. Hecker. 2006. Proteome signatures for stress and starvation in Bacillus subtilis as revealed by a 2-D gel image color coding approach. Proteomics 6:4565-4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thackray, P. D., and A. Moir. 2003. SigM, an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis, is activated in response to cell wall antibiotics, ethanol, heat, acid, and superoxide stress. J. Bacteriol. 185:3491-3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan, G., and S.-L. Wong. 1995. Regulation of groE expression in Bacillus subtilis: the involvement of the σA-like promoter and the roles of the inverted repeat sequence (CIRCE). J. Bacteriol. 177:5427-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuber, P. 2004. Spx-RNA polymerase interaction and global transcriptional control during oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 186:1911-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]