Abstract

Genes encoding subunits of photosystem I (PSI genes) in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 are actively transcribed under low-light conditions, whereas their transcription is coordinately and rapidly down-regulated upon the shift to high-light conditions. In order to identify the molecular mechanism of the coordinated high-light response, we searched for common light-responsive elements in the promoter region of PSI genes. First, the precise architecture of the psaD promoter was determined and compared with the previously identified structure of the psaAB promoter. One of two promoters of the psaAB genes (P1) and of the psaD gene (P2) possessed an AT-rich light-responsive element located just upstream of the basal promoter region. These sequences enhanced the basal promoter activity under low-light conditions, and their activity was transiently suppressed upon the shift to high-light conditions. Subsequent analysis of psaC, psaE, psaK1, and psaLI promoters revealed that their light response was also achieved by AT-rich sequences located at the −70 to −46 region. These results clearly show that AT-rich upstream elements are responsible for the coordinated high-light response of PSI genes dispersed throughout Synechocystis genome.

Photosynthetic organisms have ability to cope with the changes in light environment by modulating both the structure and the function of the photosynthetic machinery (31, 59). A typical example is the flexible control of the amounts of photosystem (PS) and light-harvesting antenna complexes depending on the availability of light energy (4, 27, 38). Under light-limiting conditions, the amount of these complexes is maintained at high level, because maximal capture of light energy is required to fulfill the energy demand of cells. Under light-saturating conditions, on the other hand, they are largely down-regulated since absorption of excess light energy tends to cause the generation of harmful reactive oxygen species (6).

The dynamics of reaction center complexes during the process of high-light (HL) acclimation have been well characterized in cyanobacteria. Amount of PSI is more strictly down-regulated than that of PSII upon the exposure to HL (28, 40). The analysis of the pmgA mutant deficient in down-regulation of PSI content revealed that the selective repression of PSI is essential for growth under continuous HL conditions (28, 54). Although the primary determinant of PSI content under HL conditions has not been identified, transcriptional regulation is likely to be one of the important factors. The cyanobacterial PSI complex is comprised of about 11 subunits, with some exceptions (23), and genes encoding these subunits (PSI genes) are dispersed throughout the genome. In Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, PSI genes are actively transcribed under low-light (LL) conditions, whereas their transcription is coordinately and rapidly down-regulated upon the shift to HL conditions (26, 29, 30, 42, 57), except for the psaK2 gene encoding an HL-inducible isoform of the PsaK subunit (19). PSI transcripts become barely detectable within 1 h of HL exposure and then gradually reaccumulate after 3 h. The change in promoter activities of PSI genes is well coincident with the change in transcript levels (42, 43), suggesting that the coordinated light response of PSI genes is achieved at the level of transcriptional regulation. In the course of HL acclimation, cells need to activate genes related to several processes such as CO2 fixation, protection from photoinhibition, and general stress management (29). The down-regulation of high promoter activities of PSI genes upon the shift to HL conditions may be important not only for the repression of PSI content, but also for the recruitment of RNA polymerases to active transcription of such HL-inducible genes.

As the first step for the elucidation of the molecular mechanism of coordinated HL response of PSI genes in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, we recently dissected the promoter architecture of the psaAB genes encoding reaction center subunits (43). The psaAB genes have two promoters, P1 and P2, both of which are responsible for the photon flux density-dependent transcription. Deletion analysis of the upstream region of psaAB fused to bacterial luciferase reporter genes (luxAB) indicated that the light responses of P1 and P2 are achieved in different manners. The cis element required for the light response of P1, designated as PE1, was located just upstream of the −35 element of P1 and was comprised of AT-rich sequence. PE1 activated P1 under LL conditions, and the down-regulation of P1 was achieved by rapid inactivation of PE1 upon the shift to HL conditions. On the other hand, the cis element required for the light response of P2, designated as HNE2, was located upstream of the P1 region, far from the basal promoter of P2. The down-regulation of P2 seemed to be attained through the negative effect of HNE2 exerted only under HL conditions.

In this report, we further proceeded with the promoter analysis of PSI genes. First, the precise architecture of the psaD promoter was determined by deletion analysis using luxAB reporter genes. We found that AT-rich sequence located just upstream of the −35 region is critical for the light response of the psaD gene, just like PE1 for the psaAB genes. Next, we examined whether such a light-responsive AT-rich sequence is conserved among PSI genes. Interestingly, AT-rich upstream region located between −70 and −46 conferred the ability of the light response to all of PSI promoters examined, which enables the coordinated expression of PSI genes dispersed throughout the genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

A glucose-tolerant wild-type strain and reporter-transformed strains of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 were grown at 31°C in BG-11 liquid medium (55) with 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.0. Unless stated otherwise, cultures were grown under continuous illumination provided by fluorescent lamps at 20 μmol photons m−2 s−1. To maintain reporter strains, spectinomycin (20 μg/ml) was added to cultures. Cells were grown in volumes of 50 ml with test tubes (3 cm in diameter) and bubbled with air. Cell density was estimated with a spectrophotometer (model UV-160A; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) as the optical density at 730 nm (OD730). HL shift experiments were performed by transferring cells at the exponential growth phase (OD730 = 0.1 to 0.2) from LL conditions (20 μmol photons m−2 s−1) to HL conditions (250 μmol photons m−2 s−1).

Escherichia coli and DNA manipulation.

XL1-Blue MRF′ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was the host for all plasmids constructed in this study. When required, ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or spectinomycin (20 μg/ml) was added to Terrific Broth medium for selection of plasmids in E. coli. Procedures for the growth of E. coli strains and for the manipulation of DNA were as described in Sambrook et al. (51). Sequencing of plasmids was carried out by the dideoxy-chain termination method using dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (ABI PRISM; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Primer extension analysis.

Primer extension analysis was carried out using 10 μg (for psaF), 15 μg (for psaE and psaK1), or 20 μg (for psaC, psaD, and psaL) of total RNA as templates. For the reverse transcription (RT) of each PSI gene, IRD (infrared dye) 800-labeled primer, psaC-1, psaD-4, psaE-1, psaF-1, psaK-1, or psaL-1 (Table 1) was used. Reverse transcription was performed as follows. Total RNA was incubated at 70°C for 10 min in a 14-μl reaction mixture containing 10 nmol each of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and 2 pmol of labeled primer. After cooling down at room temperature, 4 μl of 5× First Strand buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), 1 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, and 200 U of Superscript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were added and a reverse transcription reaction was performed at 55°C for 60 min. After incubation at 70°C for 15 min, the extension products were ethanol precipitated, resuspended in loading buffer (98% [vol/vol] formamide, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.3% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol, 0.3% bromophenol blue [wt/vol]), and denatured at 95°C for 3 min. The IRD-labeled extension products were electrophoresed and detected by a Global Edition IR2 DNA sequencer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). DNA ladders were created using a T7 sequencing kit (USB, Cleveland, OH) with the same IRD800-labeled primer as that used for reverse transcription and electrophoresed alongside the extension products.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the primers used in this study

| Name | Locationa | Sequence | Useb |

|---|---|---|---|

| PpsaD-F | −162→ | AACGTACGAATCTCCTTGCCAAAACT | C,T |

| PpsaD-R | ←+33 | AACGTACGAGGGATGAAAATGGAATT | C |

| psaD-1 | −122→ | AACGTACGACCAACCTACTGGGCGTT | C |

| psaD-2 | −92→ | AACGTACGCTCTACCCATTGTCCTGG | C |

| psaD-3 | −42→ | AACGTACGGACAAAGCCAGATGGTAA | C |

| psaD-4 | ←+68 | CCGAATTTAGGCGGTTGT | P |

| psaD-5 | ←+108 | AACGTACGTTCCCGGTTGGCTTTGGA | T |

| psaD-6 | −67→ | AACGTACGAATTTGGTGAAATGTTAC | C |

| psaD-7 | ←+2 | AACGTACGTAGGGAATCCTACCACTG | C |

| psaD-8 | ←−23 | AACGTACGGGTTACCATCTGGCTTTG | C |

| psaD-9 | ←−43 | AACGTACGAAGAACTGTAACATTTCA | C |

| psaC-1 | ←+115 | CGCATTGGGTACAACCAA | P |

| PpsaC-1 | −305→ | ACTACCCAGATAGTCTTT | T |

| PpsaC-2 | −70→ | AACGTACGATGTAACAGAATTTGAA | C |

| PpsaC-3 | −45→ | AACGTACGCGTTTTTTCCGAAAGGAA | C |

| PpsaC-4 | ←+63 | AACGTACGTGACTATCGGCTCCTTAA | C |

| psaC-R | ←+309 | TTAGTAAGCTAAACCCAT | T |

| psaE-1 | ←+143 | CAGTAGGACTCAGTGCGT | P |

| PpsaE-1 | −467→ | TGTTGTAGATAATTCTGA | T |

| PpsaE-2 | −70→ | AACGTACGTAAAGAATTGTTTTGGG | C |

| PpsaE-3 | −45→ | AACGTACGGGGGAGGGGGAGGACGC | C |

| PpsaE-4 | ←+90 | AACGTACGATTTAATTCCTTAGATA | C |

| psaE-R | ←+315 | CTATTTTGCCGCCGCTTG | T |

| psaF-1 | ←+202 | CAGAGTGTAAAGGCTAGG | P |

| PpsaF-2 | −118→ | GCCGAAAATTTGATGGGT | T |

| psaF-R | ←+641 | GATTTCTGAATCCTTCAT | T |

| psaK-1 | ←+111 | CCAGGACAGGGTGGCGGG | P |

| PpsaK-F | −69→ | AAACGAAAATTTGTTAAG | T |

| PpsaK-1 | −70→ | AACGTACGAAAACGAAAATTTGTTAA | C |

| PpsaK-2 | −45→ | AACGTACGAACGGTGGTTTCCCAGGG | C |

| PpsaK-3 | ←+63 | AACGTACGTGAGATTCTCCAGAATAA | C |

| PpsaK-R | ←+324 | TTAAAGTACTCCCATATT | T |

| psaL-1 | ←+100 | AAGGATCGCCGTTATAGG | P |

| PpsaL-F | −450→ | CAGCAAGCTCCTTAATAA | T |

| PpsaL-1 | −70→ | AACGTACGACTTAATGAATTTTTTTA | C |

| PpsaL-2 | −45→ | AACGTACGAAGCCATTTTCCTCGCAA | C |

| PpsaL-3 | ←+54 | AACGTACGTGGTATTGAGTTCTCCTA | C |

| psaL-R | ←+150 | AGTGCGGGTGAAAGCGGA | T |

The starting point and direction of each primer are indicated. Numbers refer to the nucleotide positions relative to the major transcriptional starting point indicated in Fig. 3B.

These primers were used for primer extension analysis (P), preparation of templates for the sequencing reaction (T), and preparation of reporter constructs (C). All primers used for reporter constructs include the BsiWI site (CGTACG) for cloning and an additional two adenine nucleotides at their 5′ end.

RNA isolation and RNA blot analysis.

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis were performed as described previously (42). For dot blot analysis, 5 μg of total RNA per each dot was applied as spots onto the nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). To generate luxA riboprobe, the luxA gene was amplified by PCR from pPT6803-1 vector (see below) using the primer pair luxA forward (5′-ACTTATCAGCCACCTGAG-3′) and luxA reverse (5′-TATCTTTGGCTCTATTTG-3′). To use the PCR product directly as a template for in vitro transcription, the T7 polymerase recognition site (TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGA) was added to the 5′ terminus of the reverse primer. The in vitro transcription reaction was carried out with a digoxigenin (DIG) RNA labeling kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Construction of luxAB reporter strains.

All plasmids used for transformation of Synechocystis cells were derivatives of pPT6803-1, which is a recombinational plasmid having the promoterless luxAB genes, the neutral site of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (the downstream region of the ndhB gene), and the spectinomycin resistance cassette (5, 42). Each promoter fragment was generated by PCR with primers containing the BsiWI site at their 5′ termini (Table 1) and cloned into the unique BsiWI site of pPT6803-1 to produce transcriptional fusions with the promoterless luxAB gene. The nucleotide sequence and direction of the promoter region in the reporter constructs were verified by sequencing. Wild-type Synechocystis was transformed with the pPT6803-1 derivatives, and transformants were selected and propagated in liquid BG-11 with spectinomycin. All of the reporter strains used in this study are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the strains used in this study

| Strain | Description of promoter fragment | Insert size (bp) | Primer combination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controla | |||

| D1 | −122 to +33 region of psaD | 155 | psaD-1/PpsaD-R |

| D2 | −92 to +33 region of psaD | 125 | psaD-2/PpsaD-R |

| D6 | −67 to +33 region of psaD | 100 | psaD-6/PpsaD-R |

| D15 | −52 to +33 region of psaD | 85 | pssaD-13/PpsaD-R |

| D3 | −42 to +33 region of psaD | 75 | psaD-3/PpsaD-R |

| D10 | −22 to +33 region of psaD | 55 | psaD-10/PpsaD-R |

| D7 | −92 to +2 region of psaD | 94 | psaD-2/psaD-7 |

| D8 | −92 to −23 region of psaD | 70 | psaD-2/psaD-8 |

| D9 | −92 to −43 region of psaD | 50 | psaD-2/psaD-9 |

| D12 | −67 to −43 region of psaD | 25 | psaD-6/psaD-9 |

| D13 | −122 to −43 region of psaD | 80 | psaD-1/psaD-9 |

| A61 | −69 to +2 region of psaAB | 71 | psaA-14/psaA-15 |

| A62 | −46 to +2 region of psaAB | 48 | psaA-6/psaA-15 |

| C1 | −70 to +63 region of psaC | 133 | PpsaC-2/PpsaC-4 |

| C2 | −45 to +63 region of psaC | 108 | PpsaC-3/PpsaC-4 |

| E1 | −70 to +90 region of psaE | 160 | PpsaE-2/PpsaE-4 |

| E2 | −45 to +90 region of psaE | 135 | PpsaE-3/PpsaE-4 |

| K1 | −70 to +63 region of psaK1 | 133 | PpsaK1-1/PpsaK1-3 |

| K2 | −45 to +63 region of psaK1 | 108 | PpsaK1-2/PpsaK1-3 |

| L1 | −70 to +54 region of psaL | 124 | PpsaL-1/PpsaL-3 |

| L2 | −45 to +54 region of psaL | 99 | PpsaL-2/PpsaL-3 |

luxAB reporter vector (pPT6803-1) without promoter fragment.

Measurement of bioluminescence from cells harboring luciferase reporter genes.

For in vivo bioluminescence measurements of Synechocystis cells, liquid culture of reporter strains was grown under LL conditions to an OD730 of 0.2. An aliquot (200 μl) was transferred to a reaction tube and set immediately in the luminescence counter (Lumi-counter model 2500; Microtech-Nichion, Chiba, Japan). One hundred microliters of 0.15% (vol/vol) n-decanal was injected into a reaction tube with a syringe, and bioluminescence from the cells was measured during 120 s after the injection of n-decanal. For in vivo bioluminescence measurements of E. coli cells, overnight culture was diluted 100-fold and further cultivated at 37°C until the OD600 value reached around 1.0. An aliquot (1 μl) of cultures was diluted to 200 μl with distilled water and placed in a reaction tube. The bioluminescence level was measured as mentioned above. Specific luciferase activities were calculated as relative units/OD730 and relative units/OD600 for Synechocystis and E. coli, respectively.

RESULTS

Mapping of the 5′ end of the psaD transcript.

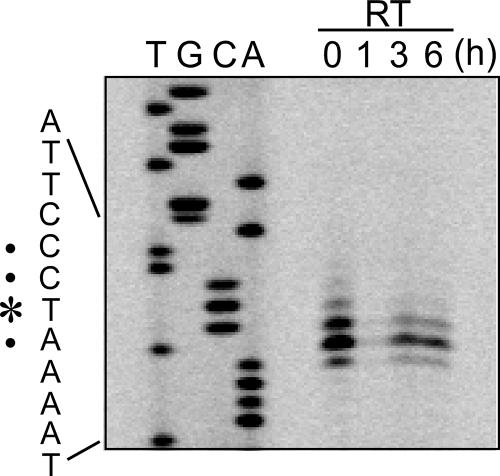

Primer extension analysis was performed to determine the 5′ end of the psaD transcript encoding the ferredoxin-binding subunit of PSI. As shown in Fig. 1, at least four 5′ ends of the transcript were mapped in a cluster when RNA samples from LL-grown cells were used as templates (lane “RT 0 h”). The major transcriptional start point was identified as a T residue positioned 33 nucleotides upstream of the start codon. A putative −10 element, TAGGAT, was found upstream of the transcriptional start point, whereas a −35 element-like sequence was not identified. RNA samples from cells exposed to HL for 1 h did not yield a detectable level of extension products (lane “RT 1 h”). After 3 h of HL incubation, however, transcription of the psaD gene resumed from the same residues as those under LL conditions (lanes “RT 3 h” and “RT 6 h”). The change in the amount of extension products was consistent with the previously reported psaD transcript levels after HL shift (29, 42).

FIG. 1.

Mapping of the 5′ ends of the psaD transcript. Total RNA was isolated from the wild-type cells incubated under HL conditions for 0, 1, 3, and 6 h and used for primer extension analysis. The detected 5′ end of the major transcript is indicated by an asterisk, and those of minor ones are indicated by dots.

Deletion analysis of the psaD gene for identification of cis elements required for the photon flux density-dependent transcription.

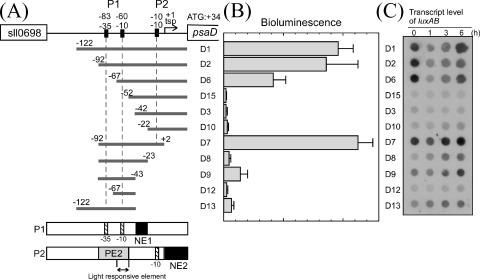

To identify cis promoter elements required for the observed HL response, a series of 5′ and/or 3′ deletion fragments of the upstream region of the psaD gene was cloned into pPT6803-1 carrying promoterless luxAB genes (Fig. 2A and Table 2). These constructs were transformed into Synechocystis cells and inserted into the neutral site of the chromosome by homologous recombination. In the previous study on the promoter structure of the psaAB genes, we observed that the level of bioluminescence and that of psaAB and luxAB transcripts showed good correlation in LL-incubated reporter strains but not in HL-incubated ones (43). Namely, the aberrant decrease in the bioluminescence level was observed under HL conditions irrespective of the luxAB transcript level, which may be due to the decline in the supply of intracellular FMNH2 required for luciferase reaction. Thus, in this study, the bioluminescence level was measured under LL conditions to compare the psaD promoter activity of each strain (Fig. 2B), whereas the level of the luxAB transcript was examined upon the shift from LL to HL conditions to follow the change in the promoter activity (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Deletion analysis of the psaD promoter region. (A) Schematic representation of a series of psaD promoter fragments with 5′ and/or 3′ deletions in reporter strains. The numbers above the promoter fragments refer to the nucleotide positions relative to the major transcriptional start point (tsp) of P2, noted as +1. The arrangement of a positive element (PE2), negative elements (NE1 and NE2), and the light-responsive element in two promoters (P1 and P2) of the psaD gene is shown below. (B) Bioluminescence levels from reporter strains grown under LL conditions. Error bars represent the standard deviation among at least four independent measurements. (C) Changes in levels of the luxAB transcripts in the reporter strains shown by dot blot analysis. Total RNA was isolated from reporter strains incubated under HL conditions for the indicated periods. Five micrograms of total RNA per dot was applied as spots to the nylon membrane and hybridized with DIG-labeled luxA probe.

As mentioned in the previous section, the major transcriptional start point of the psaD gene (noted as +1) corresponded to 33 nucleotides upstream of the start codon. Strain D10, which possessed the −22 to +33 fragment including the putative −10 element and the transcriptional start point, showed very low but substantial bioluminescence [(6.0 ± 2.0) × 105 relative units/OD730] (Fig. 2B) compared with that from the control cells having promoterless luxAB genes [(1.8 ± 0.5) × 105 relative units/OD730]. Unexpectedly, the −92 to −23 fragment also exhibited the promoter activity [strain D8, (9.0 ± 3.0) × 105 relative units/OD730]. This region contains putative −35 and −10 elements (TTGTCC and TGAAAT, respectively). Thus, it can be said that the upstream region of the psaD gene contains two promoter units, P1 and P2 (Fig. 2A).

P1 had a negative regulatory element (NE1) at the −42 to −23 region (Fig. 2B, compare D8 with D9). The region around −35 element (−92 to −68) was critical for positive regulation (Fig. 2B, compare D9 with D12). P1 activity was low under LL and gradually increased after the shift to HL conditions (Fig. 2C; see D8, D9, and D13), which is not a typical response of PSI genes. By primer extension analysis, we could not detect 5′ ends of the transcript originating from P1 even under HL conditions. P1 may be usually silenced by a certain mechanism and activated only under some specific conditions.

P2 can be regarded as the only one functional promoter of the psaD gene under the experimental conditions used in this study. The promoter activities of strains D10 (−22 to +33), D3 (−42 to +33), and D15 (−52 to +33) were substantially low, as shown in Fig. 2B. When the 5′ end was successively elongated from −52 to −92, a significant increase in the promoter activity was observed under LL conditions (Fig. 2B, see D6 and D2). This indicates the existence of a positive regulatory element for P2 in the (−92 to −53) region, designated as PE2. HL shift experiment revealed that the downstream part of PE2, the −67 to −53 region, is sufficient to confer the ability of light response to the psaD gene (Fig. 2C, compare D6 with D15). Strain D15 (−52 to +33) showed constitutively low promoter activity, whereas strain D6 (−67 to +33) exhibited a light response characteristic of PSI genes: high promoter activity under LL and its transient inactivation upon the shift to HL conditions. When the 3′ end was elongated from +2 to +33 with the fixed 5′ end at −92, the promoter activity decreased both under LL and HL conditions (Fig. 2B and C, compare D2 with D7). This indicates that the (+3 to +33) region works as a negative regulatory element (NE2), which is not involved in light response. Since both P1 and P2 contribute to the reporter activity of D7 and D2 strains, it might be possible that P1 as well as P2 is negatively regulated by NE2.

Careful comparison of the promoter architecture of the psaD gene with that of the psaAB genes (43) revealed a similar arrangement of cis elements for P1 in the psaAB genes and P2 in the psaD gene. Namely, both promoters possess a negative regulatory element at the 5′-untranslated region and a positive regulatory element located just upstream of the core promoter region. We were particularly interested in the similarity in the positive elements since these elements also worked as a light-responsive element in both promoters. The addition of the element (−69 to −47 in psaAB and −67 to −53 in psaD) to the downstream promoter fragment (−46 to +2 in psaAB and −52 to +33 in psaD) resulted in not only the enhancement of the promoter activity under LL but also the HL response characteristic of PSI genes. These observations raise the possibility that coordinated light response of PSI genes might be achieved by a positive element located upstream of the −35 region. To test the possibility, we determined the transcriptional start point of other PSI genes and examined the regulatory function of the region located just upstream of the core promoter element.

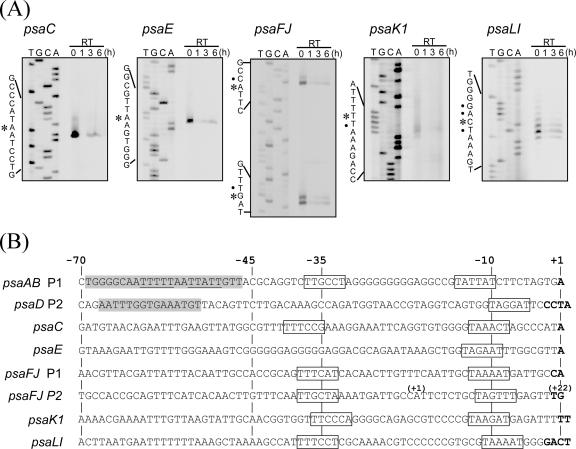

Mapping of the 5′ ends of transcripts originating from other PSI genes.

The 5′ ends of transcripts originating from other PSI genes, psaC (ssl0563), psaE (ssr2831), psaFJ (sll0819 to sml0008), psaK1 (ssr0390), and psaLI (slr1655 to smr0004), were determined by primer extension analysis (Fig. 3A). A single major transcriptional start point was identified in the promoter region of psaC, psaE, psaK1, and psaLI, whereas two major transcriptional start points spaced 20 bp apart were found in the case of psaFJ. In every PSI gene examined, no extension products were obtained using RNA samples from cells exposed to HL for 1 h, whereas small amounts were detected with those from cells incubated under HL for 3 h or 6 h. This indicates that transcription of all these genes was strictly down-regulated upon the HL shift and the repression was relieved after 3 h. Figure 3B shows the nucleotide sequences of the core promoter and its upstream region of each gene aligned according to the major transcriptional start point (+1). A putative −10 element was identified in all cases, whereas a putative −35 element was missing in several genes. Two sets of −35 and −10 elements were identified upstream of the two transcriptional start points of the psaFJ gene, indicating that this gene possesses two overlapping promoters. As shown in Fig. 3B by shading in gray, the light-responsive elements of P1 in the psaAB genes and P2 in the psaD gene are located within the −70 to −46 region. It is noteworthy that this region is rich in short A or T tracts in every PSI gene. To examine the effect of these AT-rich sequences on the promoter activity, the downstream promoter regions (−45 to a nucleotide just upstream of ATG) of psaC, psaE, psaK1, and psaLI with or without the upstream regions (−70 to −46) were fused to luxAB genes in the pPT6803-1 vector, and these constructs were introduced into Synechocystis cells. For the analysis of the psaAB promoter, strains with or without the −69 to −47 region (A61 and A62) were used (43). For the analysis of psaD promoter, strains with or without the −67 to −53 region (Fig. 2A, D6 and D15) were used. psaFJ promoters were excluded from the analysis since the arrangement of regulatory elements for two overlapping promoter is difficult to predict without precise promoter analysis.

FIG. 3.

Mapping of the 5′ ends of PSI transcripts. (A) Total RNA was isolated from the wild-type cells incubated under HL conditions for 0, 1, 3, and 6 h and used for primer extension analysis of psaC, psaE, psaFJ, psaK1, and psaLI. Detected 5′ ends of the major transcripts are indicated by asterisks, and those of minor ones are indicated by dots. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the core promoter and its upstream region of PSI promoters. Transcriptional start points are shown in boldface letters. The promoters are aligned according to the major transcriptional start point noted as +1. Putative −35 and −10 hexamers are boxed. Light-responsive positive elements identified in psaAB and psaD promoters are shaded in gray. The nucleotides shown to be critical for the light response of psaAB promoter (43) are underlined. The numbers in parentheses shown above the nucleotide sequence of the P2 promoter of psaFJ indicate the position according to the major transcriptional start point of the P1 promoter.

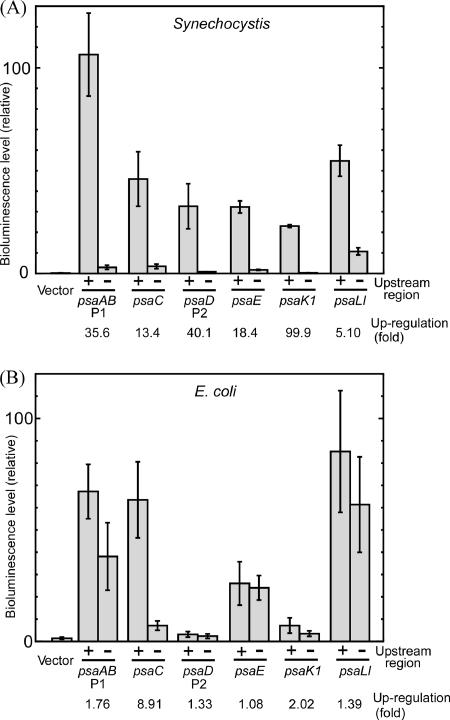

Effect of the −70 to −46 region on the promoter activity of PSI genes.

Figure 4A shows the bioluminescence level of Synechocystis cells harboring PSI promoter-luxAB reporter genes with or without the upstream region under LL conditions. The reporter activities of the downstream promoter fragments alone were generally low, but there existed some differences among them. For example, the promoter activity of the downstream region was low in the case of psaD [(8.2 ± 0.2) × 105 relative units/OD730] and psaK1 [(2.3 ± 0.4) × 105 relative units/OD730], whereas that of psaLI was significantly high [(1.1 ± 0.2) × 107 relative units/OD730]. It is possible that the high activity of the psaLI promoter is brought about by a positive regulatory element located within the downstream region. When the AT-rich upstream region was added, each promoter displayed much higher activity compared with the corresponding derivative containing only the downstream region. This demonstrates that the −70 to −46 region can work as a positive regulatory element for every PSI gene examined here. The low activity of psaD and psaK1 promoters was largely up-regulated in the presence of the upstream region by 40.1- and 99.9-fold, respectively. On the other hand, strong promoter activity of psaLI was not enhanced as much by the upstream region (5.1-fold). As a result, similar promoter activity (around 5.0 × 107 relative units/OD730) was attained among PSI genes irrespective of the activity of the downstream promoter region.

FIG. 4.

Bioluminescence levels from Synechocystis cells (A) and E. coli cells (B) harboring PSI promoter-luxAB reporter genes with (+) or without (−) the upstream region incubated under LL conditions. Error bars represent the standard deviation among at least four independent measurements. Reporter strains used for the measurement shown in panel A are as follows. psaAB P1 (+), A61 containing the −69 to +2 region; psaAB P1 (−), A62 containing the −46 to +2 region; psaC (+), C1 containing the −70 to +63 region; psaC (−), C2 containing the −45 to +63 region; psaD P2 (+), D6 containing the −67 to +33 region; psaD P2 (−), D15 containing the −52 to +33 region; psaE (+), E1 containing the −70 to +90 region; psaE (−), E2 containing the −45 to +90 region; psaK1 (+), K1 containing the −70 to +63 region; psaK1 (−), K2 containing the −45 to +63 region; psaLI (+), L1 containing the −70 to +54 region; psaLI (−), L2 containing the −45 to +54 region. E. coli cells used for the measurement shown in panel B possessed the same reporter genes as those used for panel A.

Next, we transformed E. coli cells with the above mentioned reporter constructs and measured the level of bioluminescence to see whether the upstream region can work as a positive regulatory element in E. coli cells (Fig. 4B). In all strains harboring PSI promoter-luxAB constructs, the luminescence level was higher than that of the control cells having promoterless luxAB genes [(1.4 ± 0.5) × 108 relative units/OD600], showing that PSI promoters can be recognized by RNA polymerase of E. coli. The rank orders of promoter strength are similar in both Synechocystis and E. coli cells. Namely, the activities of the downstream promoter fragments of psaD and psaK1 were low [(2.4 ± 1.0) × 108 relative units/OD600 and (3.5 ± 1.2) × 108 relative units/OD600, respectively] and that of psaLI was significantly high [(6.1 ± 2.1) × 109 relative units/OD600] also in E. coli cells. The promoter strength is not likely to be determined by the extent of the similarity of the core promoter sequence to the consensus sequence of E. coli σ70 promoters. For example, psaE promoter lacking the −35 element showed much higher activity than psaK1 promoter having a −35 element-like sequence, TTCCCA. It is noteworthy that the positive effect of the upstream region was much less evident in E. coli cells than in cyanobacterial cells. The mechanism of the positive regulation of PSI genes by the −70 to −46 region may be unique to cyanobacterial cells.

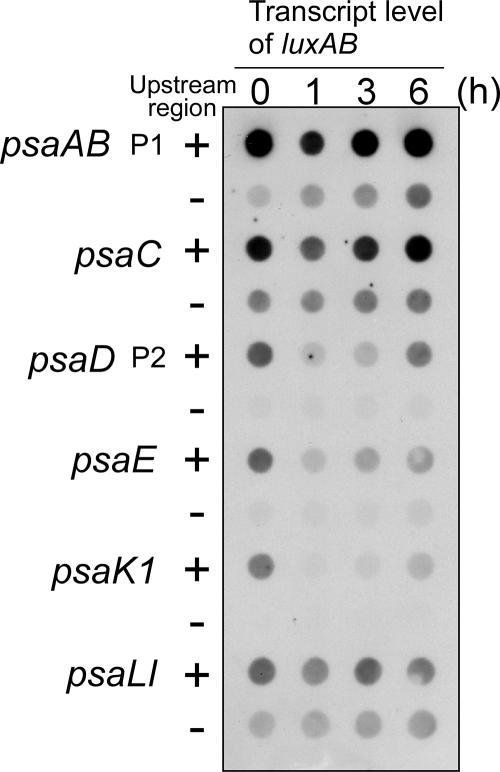

Finally, we examined if the addition of the −70 to −46 region brings about the HL response to every PSI gene. The change in the level of the luxAB transcript in reporter strains upon the shift from LL to HL conditions was examined by dot blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 5, strains having only the downstream promoter fragments did not show the light response typical of PSI genes. As is evident in psaAB, psaC, and psaL, whose downstream promoter region shows relatively high activity, a low level of luxAB transcript was detected under LL conditions and its gradual accumulation was observed after the shift to HL conditions. In contrast, in strains having promoter fragments including the upstream region, the level of luxAB transcript was considerably high under LL conditions and transiently decreased within 1 h after the shift to HL. It is obvious that the addition of the −70 to −46 region conferred the ability of the light response to every PSI promoter.

FIG. 5.

Changes in levels of the luxAB transcripts in the reporter strains shown by dot blot analysis. Reporter strains harboring PSI promoter-luxAB reporter genes with (+) or without (−) the upstream region were transferred to HL conditions, and total RNA was isolated after 0, 1, 3, and 6 h of incubation. Five micrograms of total RNA per dot was applied as spots to the nylon membrane and hybridized with DIG-labeled luxA probe. The reporter strains are the same as those used for Fig. 4.

DISCUSSION

Promoter architecture of PSI genes and mechanism of the coordinated HL response.

In this study, we searched for cis elements required for the coordinated HL response of PSI genes. The primer extension and deletion analyses revealed that the promoter architectures are different among PSI genes. The psaAB genes have two light-responsive promoters (43), whereas the psaD gene possesses one silent and one light-responsive promoter (Fig. 1 and 2A). The psaFJ genes are likely to have two light-responsive promoters whose core promoter elements are overlapped (Fig. 3). Although the overall structures of PSI promoters are not conserved, the AT-rich upstream region from −70 to −46 is found to be essential for the HL response in every PSI gene examined. Figure 6 shows the percentage of A or T residues in the −70 to −46 region of genes whose transcriptional start point has been determined in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. It is obvious that the AT content of the HL-responsive upstream region of PSI genes (average of 72.0% ± 6.5% AT) is considerably higher than that of the same region in other genes (average of 52.9% ± 12.3% AT). Although we have not examined the promoter activity of psaFJ genes, the AT content of the −70 to −46 region indicates that P1 (68% AT) but not P2 (52% AT) may be regulated by the same mechanism as that involved in the regulation of other PSI genes.

FIG. 6.

Percentage of A or T residues in the −70 to −46 region of genes in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. PSI promoters with an HL-responsive upstream region are circled. References are shown in parentheses for the following genes: prk and petH (58); glnB (21); recA and lexA (11); ntcA (2); hspA (14); groESL and groEL2 (46); sufBCDS (52); ndhR (17); gap2 (16); desA, desB, desC, and desD (34); secA (35); glnA (49); crhR (47); petF (36); slr0373 (53); psbA2 and psbA3 (39); crtB and crtP (15); icd (44); and hoxE (24).

The addition of an AT-rich upstream element to the downstream promoter region stimulated the promoter activity 5- to 100-fold (Fig. 4A), which accounts for the high abundance of PSI transcripts under LL conditions. Upon the shift to HL conditions, the positive regulation by the upstream element was suppressed within 1 h and then gradually reactivated (Fig. 5). There was good concordance between the time course change of the activity of the upstream element (Fig. 5) and the accumulation profile of PSI transcripts (Fig. 1 and 3A) after the shift to HL conditions. This observation clearly shows that the coordinated HL response of PSI genes is achieved by the AT-rich upstream element from −70 to −46. In the case of psaA, psaC, and psaL, the extent of the repression of the promoter activity after 1 h of HL exposure (Fig. 5) was far smaller than that expected from the level of products of the primer extension analysis, which was almost undetectable after 1 h (Fig. 3A). Also the extent of the reactivation of these promoters after 3 h of HL exposure (Fig. 5) was faster than that expected from the level of extension products (Fig. 3A). It is likely that these genes possess an additional regulatory element involved in the suppression of the high promoter activity. Such a negative element may be located at the region whose function was not assessed in this study (i.e., 5′-untranslated region or the region further upstream of −70). As for the P1 promoter of psaAB genes, the negative element located at 5′-untranslated region, NE1 (43), is the possible candidate for such a regulatory element.

The mechanism of HL response is dependent on the AT-rich upstream region.

For a number of different bacterial promoters, it has been shown that AT-rich sequences increase transcription when inserted upstream of the −35 element (9, 37). Although the positive effects of AT-rich sequences on transcription often have been attributed to the intrinsic curvature of these sequences (48), an enhanced binding of the RNA polymerase complex to AT-rich sequences could also explain the stimulatory effect. In E. coli, the so-called UP element, an AT-rich sequence located between −60 and −40, is known to increase transcription by interacting with the C-terminal domain of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase (α-CTD) (13, 20, 50). UP element-like sequences occur frequently in bacterial promoters (22, 25), and stimulation of transcription by the UP element has been experimentally shown in several bacterial species other than E. coli (1, 7, 18). Moreover, the amino acid residues in α-CTD responsible for DNA binding such as R265, N268, C269, G296, K298, and S299 (for E. coli, described in references 8, 20, and 41) are highly conserved in most eubacteria, including Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. This indicates the universality of the UP element-α-CTD interaction and the possibility that AT-rich upstream elements identified in this study are a sort of UP element recognized by α-CTD. Supposing that this is the case, the decline in transcriptional activity upon the shift to HL may be explained by the transient disturbance of the UP element-α-CTD interaction by a certain factor that can bind to the UP element. However, there are several observations raising questions about the actual interaction of the upstream elements of PSI genes with α-CTD. First, the upstream elements of PSI genes could not efficiently enhance the promoter activity when introduced into E. coli cells (Fig. 4B). Second, the location and arrangement of the most AT-rich sequences in PSI promoters (Fig. 3) do not coincide with those of the consensus sequence of the UP element in E. coli: −59 nnAAA(A/T)(A/T)T(A/T) TTTTnnAAAAnnn −38 (1, 12). It has been reported that UP element-like sequences found in other bacterial species show good matches to the consensus sequence (1, 12).

An alternative possibility is that AT-rich upstream elements of PSI genes may interact with a certain transcriptional activator under LL conditions. In such a case, down-regulation of the promoter activity upon the shift to HL can be attained by the transient dissociation of the activator protein. This idea is consistent with our previous data showing the effect of inhibition of protein synthesis on PSI transcript levels (42). We observed that the addition of a translational inhibitor, chloramphenicol, did not affect the decrease in PSI transcript levels upon the shift to HL conditions. On the other hand, it strongly inhibited the accumulation of PSI transcripts when cells that had been incubated under HL conditions were returned to LL. This suggests that de novo synthesis of a regulatory element or elements is required for the transcriptional activation of PSI genes under LL but not for their repression under HL. Although we attempted to isolate a protein factor or factors interacting with the upstream elements of PSI genes from crude extract of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, the binding activity has not been detected so far. Further study will be required to clarify the mechanism of HL response dependent on the AT-rich upstream region of PSI genes.

cis-regulatory elements involved in coordinated HL response in cyanobacteria.

The information on the mechanism of coordinated transcriptional regulation during HL acclimation is quite limited in cyanobacteria. Although HL-responsive cis elements of several genes have been identified (15, 16, 35, 36), there are few pieces of evidence that they work for the coordinated response of multiple genes. The exceptionally well-characterized case are HL-inducible promoters of psbAII and psbAIII (32, 33), as well as psbDII (3, 10), encoding the reaction center subunits of PSII in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. These genes possess a light-responsive element at their 5′-untranslated region, where the binding of the common protein factor(s) was detected (33). Later, Takahashi et al. (56) pointed out that a transcriptional activator, CmpR, binds to the light-responsive element of psbAII and psbAIII. However, CmpR enhances transcription of psbAII and psbAIII irrespective of light conditions and is not required for HL response per se. The mechanism of up-regulation of psbAII, psbAIII, and psbDII genes under HL remains unknown.

Compared with HL-inducible genes, genes that are down-regulated under HL have received less attention. Except for PSI promoters analyzed in this study, the promoter of the psbAI gene in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 is the only example that has been extensively characterized (45). It is of note that the AT-rich region just upstream of the −35 element was found to be critical for the down-regulation of the psbAI gene under HL. It is possible that the AT-rich upstream sequence is widely used as a light-responsive element for HL-repressible genes among cyanobacterial species. To assess the generality of AT-rich upstream sequence, more information on the promoter architecture of HL-repressible genes is required. For example, the HL response of the cpc and apc genes encoding the components of phycobilisome closely resembles that of PSI genes: they are actively transcribed under LL and strictly down-regulated within 1 h of HL exposure (29). Examination of the −70 to −46 region of such HL-repressible genes will reveal the contribution of AT-rich upstream sequence to the global change in transcript levels in response to the upshift of photon flux density.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (to M.M.) and a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (to Y.H.) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiyar, S. E., T. Gaal, and R. L. Gourse. 2002. rRNA promoter activity in the fast-growing bacterium Vibrio natriegens. J. Bacteriol. 184:1349-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfonso, M., I. Perewoska, and D. Kirilovsky. 2001. Redox control of ntcA gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Nitrogen availability and electron transport regulate the levels of the NtcA protein. Plant Physiol. 125:969-981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anandan, S., and S. S. Golden. 1997. cis-acting sequences required for light-responsive expression of the psbDII gene in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 179:6865-6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, J. M. 1986. Photoregulation of the composition, function, and structure of thylakoid membranes. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 37:93-136. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoki, S., T. Kondo, and M. Ishiura. 2002. A promoter-trap vector for clock-controlled genes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Microbiol. Methods 49:265-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asada, K. 1994. Production and action of active oxygen species in photosynthetic tissues, p. 77-104. In C. H. Foyer and P. M. Mullineaux (ed.), Causes of photooxidative stress and amelioration of defense systems in plants. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 7.Banner, C. D., C. P. Moran, Jr., and R. Losick. 1983. Deletion analysis of a complex promoter for a developmentally regulated gene from Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 168:351-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benoff, B., H. Yang, C. L. Lawson, G. Parkinson, J. Liu, E. Blatter, Y. W. Ebright, H. M. Berman, and R. H. Ebright. 2002. Structural basis of transcription activation: the CAP-alpha CTD-DNA complex. Science 297:1562-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bracco, L., D. Kotlarz, A. Kolb, S. Diekmann, and H. Buc. 1989. Synthetic curved DNA sequences can act as transcriptional activators in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 8:4289-4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bustos, S. A., and S. S. Golden. 1991. Expression of the psbDII gene in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 requires sequences downstream of the transcription start site. J. Bacteriol. 173:7525-7533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domain, F., L. Houot, F. Chauvat, and C. Cassier-Chauvat. 2004. Function and regulation of the cyanobacterial genes lexA, recA and ruvB: LexA is critical to the survival of cells facing inorganic carbon starvation. Mol. Microbiol. 53:65-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estrem, S. T., T. Gaal, W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 1998. Identification of an UP element consensus sequence of bacterial promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9761-9766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estrem, S. T., W. Ross, T. Gaal, Z. W. Chen, W. Niu, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1999. Bacterial promoter architecture: subsite structure of UP elements and interactions with the carboxy-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Genes Dev. 13:2134-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang, F., and S. R. Barnum. 2004. Expression of the heat shock gene hsp16.6 and promoter analysis in the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Curr. Microbiol. 49:192-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-González, B., I. M. Martinez-Ferez, and A. Vioque. 1998. Characterization of two carotenoid gene promoters in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1443:343-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figge, R. M., C. Cassier-Chauvat, F. Chauvat, and R. Cerff. 2000. The carbon metabolism-controlled Synechocystis gap2 gene harbours a conserved enhancer element and a Gram-positive-like −16 promoter box retained in some chloroplast genes. Mol. Microbiol. 36:44-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figge, R. M., C. Cassier-Chauvat, F. Chauvat, and R. Cerff. 2001. Characterization and analysis of an NAD(P)H dehydrogenase transcriptional regulator critical for the survival of cyanobacteria facing inorganic carbon starvation and osmotic stress. Mol. Microbiol. 39:455-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredrick, K., T. Caramori, Y. F. Chen, A. Galizzi, and J. D. Helmann. 1995. Promoter architecture in the flagellar regulon of Bacillus subtilis: high-level expression of flagellin by the sigma D RNA polymerase requires an upstream promoter element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2582-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujimori, T., Y. Hihara, and K. Sonoike. 2005. PsaK2 subunit in photosystem I is involved in state transition under high light condition in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 280:22191-22197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaal, T., W. Ross, E. E. Blatter, H. Tang, X. Jia, V. V. Krishnan, N. Assa-Munt, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1996. DNA-binding determinants of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase: novel DNA-binding domain architecture. Genes Dev. 10:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Dominguez, M., and F. J. Florencio. 1997. Nitrogen availability and electron transport control the expression of glnB gene (encoding PII protein) in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Mol. Biol. 35:723-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graves, M. C., and J. C. Rabinowitz. 1986. In vivo and in vitro transcription of the Clostridium pasteurianum ferredoxin gene. Evidence for “extended” promoter elements in gram-positive organisms. J. Biol. Chem. 261:11409-11415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grotjohann, I., and P. Fromme. 2005. Structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I. Photosynth. Res. 85:51-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutekunst, K., S. Phunpruch, C. Schwarz, S. Schuchardt, R. Schulz-Friedrich, and J. Appel. 2005. LexA regulates the bidirectional hydrogenase in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 as a transcription activator. Mol. Microbiol. 58:810-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helmann, J. D. 1995. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma A-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2351-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herranen, M., T. Tyystjarvi, and E. M. Aro. 2005. Regulation of photosystem I reaction center genes in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 during light acclimation. Plant Cell Physiol. 46:1484-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hihara, Y. 1999. The molecular mechanism for acclimation to high light in cyanobacteria. Curr. Top. Plant Biol. 1:37-50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hihara, Y., K. Sonoike, and M. Ikeuchi. 1998. A novel gene, pmgA, specifically regulates photosystem stoichiometry in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in response to high light. Plant Physiol. 117:1205-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hihara, Y., A. Kamei, M. Kanehisa, A. Kaplan, and M. Ikeuchi. 2001. DNA microarray analysis of cyanobacterial gene expression during acclimation to high light. Plant Cell 13:793-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang, L., M. P. McCluskey, H. Ni, and R. A. LaRossa. 2002. Global gene expression profiles of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 in response to irradiation with UV-B and white light. J. Bacteriol. 184:6845-6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanervo, E., M. Suorsa, and E. M. Aro. 2005. Functional flexibility and acclimation of the thylakoid membrane. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 4:1072-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, R., and S. S. Golden. 1993. Enhancer activity of light-responsive regulatory elements in the untranslated leader regions of cyanobacterial psbA genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:11678-11682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, R., N. S. Dickerson, U. W. Mueller, and S. S. Golden. 1995. Specific binding of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 proteins to the enhancer element of psbAII required for high-light-induced expression. J. Bacteriol. 177:508-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Los, D. A., M. K. Ray, and N. Murata. 1997. Differences in the control of the temperature-dependent expression of four genes for desaturases in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1167-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazouni, K., S. Bulteau, C. Cassier-Chauvat, and F. Chauvat. 1998. Promoter element spacing controls basal expression and light inducibility of the cyanobacterial secA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 30:1113-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazouni, K., F. Domain, F. Chauvat, and C. Cassier-Chauvat. 2003. Expression and regulation of the crucial plant-like ferredoxin of cyanobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1019-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAllister, C. F., and E. C. Achberger. 1988. Effect of polyadenine-containing curved DNA on promoter utilization in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 263:11743-11749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melis, A. 1991. Dynamics of photosynthetic membrane composition and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1058:87-106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohamed, A., J. Eriksson, H. D. Osiewacz, and C. Jansson. 1993. Differential expression of the psbA genes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Mol. Gen. Genet. 238:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murakami, A., and Y. Fujita. 1991. Regulation of photosystem stoichiometry in the photosynthetic system of the cyanophyte Synechocystis PCC 6714 in response to light-intensity. Plant Cell Physiol. 32:223-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murakami, K., N. Fujita, and A. Ishihama. 1996. Transcription factor recognition surface on the RNA polymerase alpha subunit is involved in contact with the DNA enhancer element. EMBO J. 15:4358-4367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muramatsu, M., and Y. Hihara. 2003. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding subunits of photosystem I during acclimation to high-light conditions in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Planta 216:446-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muramatsu, M., and Y. Hihara. 2006. Characterization of high-light-responsive promoters of the psaAB genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 47:878-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muro-Pastor, M. I., J. C. Reyes, and F. J. Florencio. 1996. The NADP+-isocitrate dehydrogenase gene (icd) is nitrogen regulated in cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:4070-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nair, U., C. Thomas, and S. S. Golden. 2001. Functional elements of the strong psbAI promoter of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 183:1740-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamoto, H., M. Suzuki, and K. Kojima. 2003. Targeted inactivation of the hrcA repressor gene in cyanobacteria. FEBS Lett. 549:57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patterson-Fortin, L. M., K. R. Colvin, and G. W. Owttrim. 2006. A LexA-related protein regulates redox-sensitive expression of the cyanobacterial RNA helicase, crhR. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:3446-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pérez-Martin, J., F. Rojo, and V. de Lorenzo. 1994. Promoters responsive to DNA bending: a common theme in prokaryotic gene expression. Microbiol. Rev. 58:268-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reyes, J. C., M. I. Muro-Pastor, and F. J. Florencio. 1997. Transcription of glutamine synthetase genes (glnA and glnN) from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 is differently regulated in response to nitrogen availability. J. Bacteriol. 179:2678-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ross, W., K. K. Gosink, J. Salomon, K. Igarashi, C. Zou, A. Ishihama, K. Severinov, and R. L. Gourse. 1993. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 262:1407-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 52.Seki, A., T. Nakano, H. Takahashi, K. Matsumoto, M. Ikeuchi, and K. Tanaka. 2006. Light-responsive transcriptional regulation of the suf promoters involved in cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Fe-S cluster biogenesis. FEBS Lett. 580:5044-5048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh, A. K., and L. A. Sherman. 2002. Characterization of a stress-responsive operon in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Gene 297:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sonoike, K., Y. Hihara, and M. Ikeuchi. 2001. Physiological significance of the regulation of photosystem stoichiometry upon high light acclimation of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 42:379-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanier, R. Y., R. Kunisawa, M. Mandel, and G. Cohen-Bazire. 1971. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green alga (order Chroococcales). Bacteriol. Rev. 35:171-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi, Y., O. Yamaguchi, and T. Omata. 2004. Roles of CmpR, a LysR family transcriptional regulator, in acclimation of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 to low-CO2 and high-light conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 52:837-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tu, C.-J., J. Shrager, R. L. Burnap, B. L. Postier, and A. R. Grossman. 2004. Consequences of a deletion in dspA on transcript accumulation in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. J. Bacteriol. 186:3889-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Thor, J. J., K. J. Hellingwerf, and H. C. Matthijs. 1998. Characterization and transcriptional regulation of the Synechocystis PCC 6803 petH gene, encoding ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase: involvement of a novel type of divergent operator. Plant Mol. Biol. 36:353-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walters, R. G. 2005. Towards an understanding of photosynthetic acclimation. J. Exp. Bot. 56:435-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]